REGIONAL TRADE AND ECONOMIC GROWTH OF EAST AFRICA COMMUNITY STATES

JORAM MBURU MAINA

A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF APPLIED ECONOMICS IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR

THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ECONOMICS (INTERNATIONAL TRADE & FINANCE) OF KENYATTA UNIVERSITY.

ii

DECLARATION

This research project is my original work and has not been submitted in any other

university for a degree award.

Signed: ... Date ...

Joram Mburu Maina

B.A.

K102/PT/12759/2009

This research project has been submitted for examination with my approval as university

supervisor:

Signed: ... Date...

Dr. Samuel Muthoga

Department of Economic Theory

School of Economics

iii

DEDICATION

This research project is dedicated to my wife Pauline for her continuous encouragement

and moral support during the period I was writing this paper and my beloved daughters

iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To begin with, let me thank the Almighty God for giving me wisdom, knowledge and

understanding throughout my study period. My heartful thanks go to my parents Johnson

Maina and Veronica Wangari for their upbringing and supporting my education and

career path. Many thanks to all people of goodwill who have helped me complete my

studies through their prayers and resource donations. Special thanks to my supervisors,

Dr. Samuel Muthoga and the late Dr. Steve Makori for their invaluable guidance, wide

knowledge in the subject matter and ideas that made this research work complete. Last

but not least, I also wish to recognize my fellow students David Muthui, Lukas Musembi,

Kelvin Mugi and Abraham Waweru for their supportive ideas and constructive feedback

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DECLARATION... ii

DEDICATION ... iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... iv

LIST OF TABLES ... viii

LIST OF FIGURES ... x

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ... xi

OPERATIONAL DEFINITION OF TERMS ... xiv

ABSTRACT ... xv

CHAPTER ONE... 1

INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1 Background ……….. 1

1.1.1 Regional Integration Overview……… 1

1.1.2 East African Countries Regional Trade Integration………. 2

1.1.3 The Objectives, Challenges and Benefits of EAC Regional Trade Integration …….. 3

1.1.4 Regional Trade and Economic Performance Overview ……….. 6

1.2 Statement of the Problem ... 14

1.3 Research Questions ... 15

1.4 Research Objectives ... 15

1.5 Significance of Study ... 16

1.6 Study Scope ... 16

1.7 Study Organization ... 17

CHAPTER 2 ... 18

vi

2.1 Introduction ... 18

2.2 Theoretical Literature ... 18

2.2.1 Trade Theories ……….. 18

2.2.2 Growth Theories ……… 21

2.2.3 Relationship between Trade and Economic Growth ………. 22

2.3 Empirical Literature ... 23

2.4 Overview of Literature ... 29

CHAPTER 3 ... 30

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY ... 30

3.1 Introduction ... 30

3.2 Research Design ... 30

3.3 Theoretical Framework ... 30

3.4 Empirical Model ... 36

3.5 Definition and measurement of variables ... 37

3.6 Data Sources, Type and Refinement ... 38

3.7 Granger Causality Test ... 39

3.8 Data Analysis and interpretation of results... 39

3.8.1 Fixed Effects Model ……….. 39

3.9 Diagnostic Test ... 40

3.9.1 Panel Root Test ………. 40

3.9.2 Tests for Autocorrelation ……….. 41

CHAPTER FOUR ... 42

FINDINGS, INTERPRETATION AND DISCUSSION ... 42

4.1 Introduction ……….. 42

vii

4.3 Relationship between EAC Trade and the Region’s Economic Growth ……….. 45

4.4 Fixed effect Model Estimation ……….… 56

CHAPTER FIVE ... 61

SUMMARY, POLICY IMPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ... 61

5.1 Introduction ………... 61

5.2 Summary ………... 61

5.3 Conclusions ………63

5.4 Policy Implications ……… 64

5.5 Areas for Further Studies ………. 65

REFERENCES ... ... 66

viii

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1.1: EAC Trade between 2000-2013 in (US dollars) ... 8

Table 1.2: Total Trade between years 2000 and 2013 (Dollars)... 11

Table 1.3: Real GDP growth rates ... 13

Table 3.1: Table of Variables used in the Model ... 38

Table 4.1: Summary of variables and data sources ... 43

Table 4.2: Descriptive Analysis: 2001-2014 ... 44

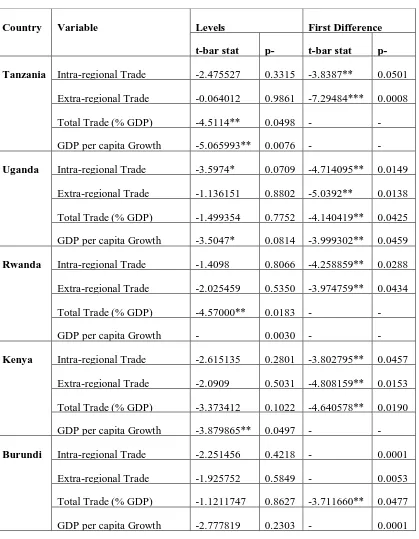

Table 4.3: Unit root tests (ADF unit root test) ... 46

Table 4.4: Granger Causality test for Kenya ... 50

Table 4.5: Granger Causality test for Tanzania ... 52

Table 4.6: Granger Causality test for Rwanda ... 53

Table 4.7: Granger Causality test for Uganda ... 54

Table 4.8: Granger Causality test for Burundi ... 55

Table 4.9: Fixed effect Model Estimation Summary ... 57

Table A1: Johansen Cointegration Test Results for GDP per capital growth and Intra-regional Trade ... 75

Table A2: Johansen Cointegration Test Results for GDP per capital growth and Extra-regional Trade ... 76

Table A3: Johansen Cointegration Test Results for GDP per capital growth and Total Trade ... 77

Table A4: Lag selection criteria for GDP per capita growth and Intra-regional Trade .... 78

Table A5: Lag selection criteria for GDP per capita growth and Extra-regional Trade ... 79

Table A6: Lag selection criteria for GDP per capita growth and Total Trade ... 80

ix

Table A9: VAR regression model for GDP per Capita Growth and Extra-regional Trade

... 83

Table A10: VAR regression model for GDP per Capita Growth and Intra-regional Trade ... 84

Table A11: VEC for GDP per Capita Growth and Extra-regional Trade ... 85

Table A12: VAR model for GDP per capita growth and Total trade for Uganda ... 86

x

LIST OF FIGURES

xi

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

ADF Augmented Dickey Fuller

AGE Applied General Equilibrium

AGOA Africa Growth and Opportunities Act

AIC Akaike Information Criterion

ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations

CACM Central American Common Market

CGE Computable General Equilibrium

COMESA Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa

EAC -US TIP East Africa Community and United States of America Trade and Investment Partnership

EAC East African Community

EAC-CU East Africa Community Customs Union

EAMU East Africa Monetary Union

EC European Commission

xii

ESRF Economic and Social Research Foundation

EU European Union

FDI Foreign Direct Investment

FTA Free Trade Area

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GMM Generalized Method of Moments

GTAP Growth Trade Analysis Project

MERCOSUR Mercado Comúndel Sur (Common Market of the South)

MFN Most Favoured Nations

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PTA Preferential Trade Area

RTA Regional Trade Arrangement

SADC South African Development Council

SIC Schwarz Information Criterion

SID Society for International Development

xiii

UDEAC Union Douanièreet Economique de l'Afrique Centrale

VAR Vector Auto-Regressive

xiv

OPERATIONAL DEFINITION OF TERMS

Causality: This is the existence of a relationship between two variables specifically in

cases where one variable causes some effects on another.

Steady state: Refers to a situation in which the various quantities grow at constant rates

Trade creation: Is when imports are substituted for domestic products as a result of being

a member of the same RTA as the trade partner, that is, it implies an increase in trade

between trade partners due to both joining a common RTA.

Trade diversion: This occurs after a change in the level of exports from a non-member (or

a member) importer to a member (or a non-member) due to the RTA. It can lead to

decrease or increase in trade among the RTA members.

Intra-regional trade: This refers to trade that occurs between countries within the same

geographical region.

Extra-regional trade: This refers to trade between members of a trading bloc and other

non-member countries using a Common External Tariff.

Regional Trade: This refers to trade within a trading bloc amongst its members and also

xv

ABSTRACT

1

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background

1.1.1 Regional Integration Overview

According to Haarlow (1997), regional integration is the process by which countries

in a specific geographical region cooperate and work together towards the attainment

of economic growth and stability. This view is supported by Lee (2003). Better

regional trade integration is achieved when member states in a trading block deepen

their trading ties through promoting free movement of goods and people along

borders, reducing trade tariffs, developing skilled human capital and avoidance of

armed conflicts between them among many other things (Davoodi, 2012).

Balassa (1961) and Jovanovic (1992) classified integration schemes into five levels

that are based on their degree of integration. A Preferential Trade Agreement (PTA) is

a trading bloc that reduces tariffs for certain goods produced by the participating

countries. According to Bhagwati and Panagariya (1993) and Grossman (1995),

member countries belonging to a Free Trade Area (FTA) agree to eliminate tariff and

non-tariff barriers amongst themselves while retaining some control over trade with

other countries not party to the agreement. With regards to Customs Union, member

countries determine jointly a tariff level among their members and agree some

uniform custom and policy during trade with other independent countries. A Common

Market has all elements in a customs union, there is free movement of goods and

people across borders although restrictions for mobility are retained against

non-member countries. According to Baldwin (1994) and Salvatore (1998) an Economic

2

than an FTA, customs union or common market. In most cases, the union coordinates

all the fiscal and monetary policies of constituent member states. The end result may

be a political union where member countries lose national sovereignty to a

supranational political authority like the envisaged European Union (EU) currently at

monetary union stage.

The benefits expected from regional integration are reduced prices of goods and

services due to a free market, increased economic welfare of society, improved trade

policies and improved productivity of workers which brings about economies of scale

due to enlargement of the market. The numerous benefits at different stages of

integration may result from either of the effects brought about by the varying degrees

of regional integration (José& Lorenzo, 2012).

1.1.2 East African Countries Regional Trade Integration

The earliest form of regional integration arrangements in East Africa was a customs

union which took place in 1917 involving Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. The

members signed a division of assets and liabilities agreement in 1984 after dissolution

of the former EAC in 1977 (Deya, 2007).

A Permanent Tripartite Commission of East Africa was then formed in November

1993 to focus on the regional cooperation aspects. This commission would later

become the policy-making organ of Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania union. On 14th

March 1996 a Secretariat of the Permanent Tripartite Commission was established and with its headquarters located in Arusha Tanzania (Ndung’u, 2000). Following the

need to guard regional cooperation, plans were then established with the view of

3

engagement and public participation, the EAC establishment agreement was signed on 30th November 1999 in Arusha, Tanzania (Ndung’u, 2000). The treaty became

enforced on 7th July 2000 following completion of its ratification procedure. On 2nd

March 2004, EAC Summit agreed to establish a customs union which later became

operational on 1st January 2005. In the year 2007 the EAC treaty was signed by two

more members i.e. Rwanda and Burundi. The two new members would later join the

EAC Customs union on 1st July 2009. The EAC Common Market Protocol was then

enforced after all member states ratified the same in July 2010. Currently, there is an

ongoing discussion towards the formation of a monetary union which is expected to

strengthen the economies of all member states, assist them adapt to global concerns

such as climate change and take advantage of all trade opportunities in the global

arena SID, (2011).

1.1.3 The Objectives, Challenges and Benefits of EAC Regional Trade Integration

The EAC treaty spells out that the community shall pursue all available measures of

fostering integration across a number of priority sectors such as research and

development, defense, political and economic affairs among others. As defined in the

Article 5 paragraph 2 of EAC Treaty (2002), the member countries agreed to create in

phases a Customs Union and then progress to other high levels of integration with a

political Federation being the ultimate aim. This was aimed at strengthening industrial

cooperation, increase infrastructural developments and increase socio-cultural

4

The establishment of a new EAC emanated from various concerns such as the desire

for industrialization, need to reduce unemployment, achievement of high economic output, reduction of economic debts and the need to reduce poverty levels (Ndung’u,

2000). In addition, there was poor infrastructure, lack of macroeconomic stability,

poor health and education indicators and little technological readiness which

challenges could be tackled with the revival of EAC (Hartzenberg, 2011). According

to the World Economic Forum 2010, key hindrances to business in the EAC region

include limited access to finance, high levels of corruption, excessive taxation, and

slow infrastructural development. Generally, the problems facing the East African

Community can be categorized into four categories namely economic, political social

and financial struggles (Kamala, 2006). The Common Market of the region also faces

a number of challenges. Firstly, the market has been unable to equally balance all

benefits achieved among all the member states. There has been discontentment among

some countries which feel that their counterparts enjoy the greater share of benefits.

Secondly, the common market has faced serious challenges in generating constant

benefits for itself. This has been mainly due to the existence of bigger regional trade

blocs which divert trade benefits to other parts of the African continent. Moreover, the

EAC Common market faces a lot of uncertainty with regards to the best approach to

be used in transforming the common market into a monetary union. Finally, the

market is still looking for ways of advancing the existing common market and

customs union (Davoodi, 2012).

Since inception, the East African Community has achieved a number of benefits. For

instance, the community has registered increased trade among its member states by

5

increased tremendously as compared to the years before. Further, the EAC member

states now boast of reduced inflation levels brought about by the influence of the

collective economic policies that have been put in place (EAC; Mwapachu, 2011).

There have been recent achievements made in EAC regional integration according to

EAC Trade report 2013. For instance, to deepen customs union, the Single Customs

Territory was rolled out in 2014. To deepen trade integration particularly

intra-regional trade, there has been significant reduction of Non-Tariff barriers with the

EAC legislation passed recently to effectively remove non-tariff barriers paving the

way for the creation of 15 one stop border posts on the member states common

borders and revising rules of origin. Other measures taken to boost regional trade are

signing of tripartite trade agreements with other trade blocks like COMESA and

SADC, EAC-EU-EPA negotiations making substantial progress and export promotion

activities like AGOA and EAC-US Trade and Investment Partnership (TIP) with US

gaining momentum. The State of East Africa 2013 Report shows that the value of

regional trade increased from $1 billion to $ 5 billion between the years 2010 and

2012. In addition, the region recorded high imports values that even were in excess of

double the value of exports realized. The top five imports and exports value stood at

$18 billion and $7 billion respectively.

The attainment of a GDP growth of 7% as a minimum target annually will enable East

Africa meet one of the criteria for macroeconomic convergence in fiscal and monetary

harmonization of East Africa (Fondad, 2005). According to the EAC Development

and Growth Strategy (2016) the attainment of macroeconomic stability is a key focus

6

economic growth such as low inflation rates and high national savings rates have not

yet been achieved as set out during the 3rd EAC Development Strategy (2006-2010).

The 4th EAC Development Strategy notes that cross-border trade clearance delays,

lack of automated systems, bureaucracy and general lack of cooperation have been

serious challenges to effective trade and by extension economic development of the

region. Such problems have given East African countries poor trade logistics as per

the World Bank ease of doing business report of 2010.

It is clear that there is an increase in imports from outside EAC and low intra-regional

trade in EAC. Also, another concern is that, since trade has grown but food imports

has dominated imports from outside the region, it might be regional integration could

have led to more trade diversion than trade creation in some sectors. Therefore, there

is need to study the trade patterns, study trends in imports and exports and analyze the

factors that are behind the performance in regional trade and assess the contribution on

the variable of importance; economic growth.

1.1.4 Regional Trade and Economic Performance Overview

It is possible to analyze the performance of regional trade integration of EAC from

various macroeconomic indicators and compare the individual member countries

economic characteristics.

According to the Fourth EAC Development Strategy (2011-12 to 2015-16), the East

African Community aims at achieving high levels of economic growth among all its

member states characterized by high levels of cooperation. This study can analyze the

7

ascertain whether the enhanced trade has also contributed to greater economic growth

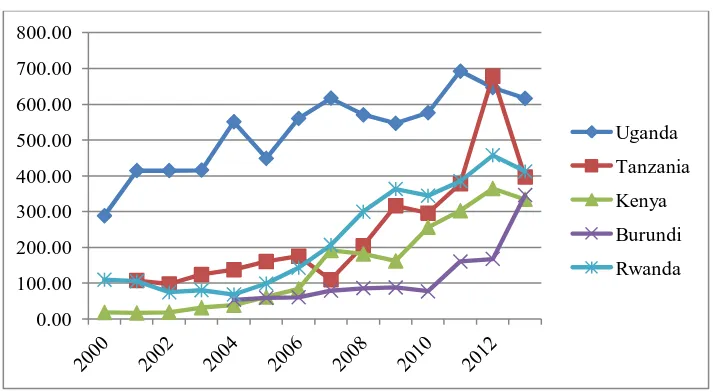

and by what extent. As depicted in Table 1.1 below on intra-EAC trade, intra-EAC

regional trade performance is growing.

The volume of intra-EAC total trade has been growing though not consistently, with

the period 2011 to 2012 recording a high growth of between 20% and 21% according

to EAC Trade Report. All the member countries recorded an increase in total

Intra-EAC trade in 2013 apart from Kenya.

The value of total regional imports dropped to 2,107 US dollars from 2,315.7 US

dollars between the years 2012 and 2013 while trade value between EAC countries

and other non-member states shifted from 3,155 US dollars to 3,698 US dollars in the

same period. Plotting a graph may provide insight into the trend of member countries

intra-EAC trade for the period under study. See below Figure 1.1 on Intra-EAC

Imports.

The volume of intra-EAC imports has been growing steadily in all the EAC countries

but declined for the period 2012 and 2013. Some of the reasons attributed to this are

the pressure on the local currencies due to the growing import bill outside the region

where the five leading exports cannot meet half the value of five leading imports in

the region.

Also, the countries lowered the external common external tariff on some commodities

hence could have resulted in import substitution from outside the region like for

8

Table 1.1: EAC Trade between 2000-2013 in (US dollars)

20 00 200 1 200 2 200 3 200 4 200 5 200 6 200 7 200 8 200 9 201 0 201 1 201 2 201 3 Imports Uganda 28

8.6 415 .0 414 .9 416 .3 551. 5

449 560. 6

617. 4

570. 6

547 576. 5 692. 6 646. 9 616. 6 Tanzani a 107 .8 97. 9 124 .2 137. 8 160. 5 175. 5 110. 1 205. 0 316. 9 295. 9 378. 1 678. 6 397

Kenya 1 8.5 17. 0 19. 1 31. 7

38.4 61.5 84.1 191. 6 182. 0 162. 5 256. 8 302. 9 365. 1 334. 5 Burundi - - - - 54.1 59.1 60.9 79.5 86.5 88.2 77.2 160.

8

168. 1

346. 4 Rwanda 11

0.0 105 .9 74. 6 80. 7

68.9 99.1 143. 4 207. 1 299. 8 363. 5 344. 6 385. 1 457. 8 412. 5 Total 41

7.1 645 .7 606 .5 652 .9 850. 7 829. 2 1,02 4.5 1,20 5.7 1,34 3.9 1,47 8.00 1,55 1.00 1,91 9.50 2,31 6.50 2,10 7.00 Exports Uganda 87.

2

86 114 .7

132 144. 7 296. 3 476. 9 654. 7 377. 4 398. 8 428. 6 503. 7 580. 3 627. 4 Tanzani a 58. 6 57. 1 102 .4 123. 8 128. 9 157. 8 205. 9 310. 5

285 394. 3

409 613. 3

1,11 8.00 Kenya 44

8.6 6 22. 5 667 .2 71 0.5 810. 1 974 .3 735 .8 952. 2 1,03 6.60 1,16 7.20 1,27 8.7 1,54 4.40 1,59 6.40 1,45 1.0 Burundi 5.4 4.0 5.5 5.3 18.1 20.2 18.6 28.3 24.9 35.1

9 Rwanda 2

3.9 16 4.2 35. 1 29. 0 25. 0 34. 9 33. 0 40. 0

37.9 93.2 50.4 81.2 343. 5

467

Total 55 9.7 93 1.3 87 4.1 97 3.9 1,1 09 1,4 38.4 1,4 09 1,85 8.1 1,78 0.50 1,96 4.40 2,17 0.60 2,56 6.60 3,15 8.40 3,69 8.59 Total EAC Trade Value

Uganda 37 5.8 50 1 52 9.6 54 8.3 696 .2 745 .3 103 7.5 1,2 72.1

948 945. 8 1,00 5.10 1,19 6.30 1,22 7.20 1,24 4.00 Tanzani a 16 6.4 15 5.0 22 6.6 261 .6 289 .4 333 .3 316 .0 515. 5 601. 9 690. 2 787. 1 1,29 1.90 1,51 5.00 Kenya 46

7.1 63 9.5 68 6.3 74 2.2 848 .5 1,03 5.8 819 .9 1,1 43.8 1,21 7.60 1,33 2.00 1,53 6.80 1,84 7.20 1,95 7.30 1,78 5.50 Burundi 59.

5 63. 1 66. 4 84. 8 104. 6 108. 4

95.8 189. 1

193 381. 6 Rwanda 13

3.9 27 0.1 10 9.7 10 9.7 93. 9 134 .0 176 .4 247 .1 337. 7 456. 6

395 466. 2

801. 3

879. 5 Total 97

6.8 1,5 77 1,4 80. 6 1,6 26. 8 1,9 59.7 2,2 67.6 2,4 33.5 3,0 63.8 3,12 4.40 3,44 2.40 3,72 1.60 4,48 6.10 5,47 0.90 5,80 5.59

9

Figure 1.1: Intra-EAC Imports, 2000-2013 (US$ Million)

Likewise, a graph can be plotted to check the trend of Intra-EAC exports over the

years. See Figure 1.2 below

Figure 1.2: Intra-EAC Exports, 2000-2013 (US$ Million)

The graph above shows a steady growth in Intra-EAC exports over the period 2000 to

2011 for some countries while others have stagnated over the same period. The

growth can be attributed to the EAC establishment treaty signed in 2000 and signing

of the treaty for a Customs Union in 2004, the expansion of the market when Rwanda

and Burundi joined in 2009 and eventually the signing of the common market protocol

in 2011 liberalizing the regional market. The recession in the European Euro Zone in 0.00

100.00 200.00 300.00 400.00 500.00 600.00 700.00 800.00

Uganda Tanzania Kenya Burundi Rwanda

0.00 200.00 400.00 600.00 800.00 1,000.00 1,200.00 1,400.00 1,600.00 1,800.00

10

2012/13 could have contributed if what is exported within the region is for

manufacture for export market. From 2012 to 2013 there is decline for Kenya whereas

Tanzania and Rwanda have increased significantly their exports to EAC partner states.

Kenya held general election in the first quarter of 2013 and the wait and see attitude of

many producers then could have impacted negatively. In addition, there was reduction

of mineral fuels exports as a result of oil refinery closure in Mombasa. Tanzania and

Rwanda recorded a significant increase in exports to Kenya.

Plotting a graph in total trade (Intra-EAC exports plus Intra-EAC imports) reveals that

Intra-EAC imports and Intra-EAC exports show a similar trend. See Figure 1.3 below.

Figure 1.3: Intra-EAC Total Trade, 2000-2013 (US$ Million)

From figure 1.3 above, volume of trade has been increasing steadily during the period

2000 to 2011. Thereafter, Uganda and Kenya recorded a decline in 2013. Rwanda,

Burundi and Tanzania have recorded a tremendous increase during the period 2012

and 2013. The possible reasons can be associated with import and exports patterns

explained above. 0.00

500.00 1,000.00 1,500.00 2,000.00 2,500.00

11

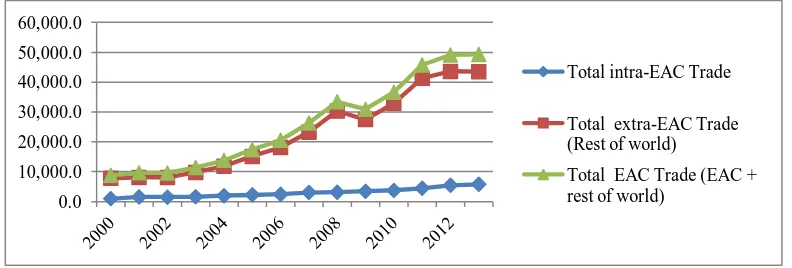

Table 1.2 below shows the trade volumes between intra-regional and extra-regional

trade for EAC.

Table 1.2: Total Trade between years 2000 and 2013 (Dollars)

Years 200 0 200 1 200 2 200 3 200 4 200 5 200 6 200 7 200 8 200 9 201 0 201 1 201 2 201 3 Total intra-EAC Trade 976. 80 1,57 7.00 1,48 0.60 1,62 6.80 1,95 9.70 2,26 7.60 2,43 3.50 3,06 3.80 3,12 4.40 3,44 2.40 3,72 1.60 4,48 6.10 5,47 0.90 5,80 5.59 Total extra-EAC Trade 7,82 6.22 8,05 7.53 8,07 7.37 9,77 3.93 11,8 50.8 8 15,1 30.8 0 18,1 00.7 7 23,2 56.4 8 30,3 09.7 7 27,4 81.8 5 32,9 03.0 4 41,3 04.1 5 43,6 00.3 7 43,4 82.5 7 Total EAC Trade 8,80 3.02 9,63 4.53 9,55 7.97 11,4 00.7 3 13,8 10.5 8 17,3 98.4 0 20,5 34.2 7 26,3 20.2 8 33,4 34.1 7 30,9 24.2 5 36,6 24.6 4 45,7 90.2 5 49,0 71.2 7 49,2 88.1 6

To have a comparison of intra-EAC total trade and extra-EAC trade plot a graph

below to show the trend.

Figure 1.4: Intra-EAC Total Trade and Extra-EAC Total Trade 2000-2013 (US$ Million)

The figure above depicts that the extra-regional trade forms the bulk of the total trade

and increased more than intra-regional trade during the periods 2004 to 2008 and 2009

to 2012.

This can be illustrated in figure 1.5 below more clearly by comparing the percentages

of intra and extra regional trade to total trade. 0.0 10,000.0 20,000.0 30,000.0 40,000.0 50,000.0 60,000.0

Total intra-EAC Trade

Total extra-EAC Trade (Rest of world)

12

Figure 1.5: Percentage of Intra-EAC Trade and Extra-EAC Trade to Total Trade

The figure above shows that the percentage of Intra-EAC Trade to Total Trade ranges

between 9.3% and 16.4% while percentage of Extra-EAC Trade to Total Trade has

ranged between 83.6% and 90.7% during the period 2000 to 2013. Both extra-regional

trade and intra-regional trade stagnated at about 11% and 88% respectively.

The study can focus on the trend of other variable of interest which is economic

growth. Table 1.3 below shows the economic growth performance of the EAC

member countries since 2000. For instance, in the year 2013, Tanzania had the highest

growth rate with Kenya and Burundi following closely. Kenya had a high per capita

income compared to other countries while Burundi was the last in this category (EAC

2014). However, in the last 5 years Rwanda has been leading with an economic

growth as can be illustrated in the table below.

The data below shows that there has been a varying GDP growth rate among the EAC

member states. Rwanda and Uganda have performed well on average while Kenya

and Burundi have been trailing behind. 0.0%

10.0% 20.0% 30.0% 40.0% 50.0% 60.0% 70.0% 80.0% 90.0% 100.0%

% of Intra-EAC Trade to Total Trade

13

Table 1.3: Real GDP growth rates

Partner State 2000 20012002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

Burundi (0.9) 2.1 4.5 (1.2) 4.8 0.9 5.4 3.5 4.9 3.8 5.1 4.2 4.2 4.8

Tanzania 4.9 6.0 7.2 6.9 7.8 7.4 6.7 7.1 7.4 6.0 7.0 6.4 6.9 7.0

Uganda, 2002=100 4.4 6.5 4.7 6.2 5.8 10.0 7.0 8.1 10.4 4.1 6.2 6.2 6.9 5.8

Kenya 0.6 4.5 0.6 2.8 4.9 5.7 6.1 7.0 1.5 2.7 5.8 4.4 4.6 4.7

Rwanda, 2006=100 6.0 9.7 11.0 0.3 5.3 7.2 6.5 7.9 11.2 6.2 7.2 8.2 8.0 4.6

Source: EAC Macroeconomic Statistics – 2014)

This is reflected in the graphical representation in Figure 1.6 below.

Figure 1.6; Growth Rate for East African states by year

Source: Constructed from Table 1.3 above - Real GDP growth rates -2

0 2 4 6 8 10 12

14

The graph above shows the countries have had differing trends at different times.

Tanzania has been having a more stable growth pattern while Burundi has had the

most erratic growth pattern in the beginning but normalizes from 2011. Rwanda

recorded high growth between 2000 and 2002 before recoding a significant decline in

2003. Thereafter, Rwanda recoded impressive growth until 2008 and has been on a

downward trend since then. Kenya recorded significant decline in 2003 and worse

decline in 2008 mainly attributed to the post-election violence. The decline in 2009 in

all EAC countries was instigated by high fuel prices and the global financial crisis among other factors such as Kenya’s struggle with the effects of post-election

violence. Uganda has been recording a steady growth apart from 2009. However, from 2010 to 2013, the individual countries’ growth rates have been showing a slowdown

with a declining trend yet over this period trade has grown tremendously in most

countries.

1.2 Statement of the Problem

While total intra-regional trade shows an increasing trend over the period between

2002 and 2013 for the EAC member countries, the extra-regional trade seems to be

growing faster yet their proportions to total trade shows they are almost constant.

Economic growth on the other hand has not been consistent as it has been varying

over the years more than would be expected. Intra-regional trade is expected to drive

the economic growth of the East African countries but its proportion relative to total

trade is ranked the lowest among other RTAs like EU, NAFTA and SADC (Ouma,

15

One of the provisions to increase the EAC intra-trade leading to the formation of the

EAC is Article 75 of the Treaty and the Customs Union (CU) Protocol. It provides a

number of elements which include (i) elimination of internal tariffs and other charges

of equivalent effect (ii) elimination of non-tariff barriers; (iii) establishment of a

Common External Tariff (CET); (iv) duty drawback, refund and remission of duties

and taxes, among others. It was anticipated that implementation of these provisions

would increase the value and volume of trade within the EAC (Shinyekwa S. &

Othieno L., 2013).

GDP growth rate analysis shows a major disconnect between deepening integration

and achievement of growth within a common market stage. Thus there is need to find

out why economic growth has dwindled yet major strides have been experienced

especially in recent years following integration efforts. Therefore, one may ask

whether economic growth is influenced by regional integration.

1.3 Research Questions

i. What is the relationship between regional trade of EAC states and economic

growth?

ii. What is the contribution of extra-regional and intra-regional trade in economic

growth of EAC states?

1.4 Research Objectives

i. To establish the relationship between regional trade of EAC states and

16

ii. To establish the influence of regional trade by comparing the contribution of

extra-regional and intra-regional trade on economic growth in EAC states.

1.5 Significance of Study

This research has established the contribution of the EAC trade integration to regional

economic growth and establishes whether or not the regional integration has increased

trade among its constituent member states. Various factors that either enhance or

inhibit regional trade have also been identified and the specific measures that need to

be adopted by policy makers towards generating more benefits for all parties have

been outlined.

No studies have been done explicitly to compare the differential impacts of

intra-regional and extra-intra-regional trade on the growth of GDP in RTAs in African countries

especially EAC member countries. Therefore, this study has made a contribution in

closing that research gap.

1.6 Study Scope

This research lays its primary focus on economic growth with regard to regional

integration among the EAC member states. The EAC member countries included here

are Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi. The period of the study is from

2001 when EAC was reborn to 2014 based on availability of secondary data.

Macro-economic variables affecting regional integration and Macro-economic growth have been

taken into account and a model developed using measurable variables. This study

relied on secondary data from published data sources. These published sources include

EAC Macroeconomic statistics (2014), East African Community Facts and Figures

17

The study borrowed from works of other researchers without duplicating their work

and possibly addresses various concerns not outlined in previous researches.

1.7 Study Organization

The research is arranged into five chapters. The first chapter outlines the background

details of this study, objectives to be achieved and the statement of the problem.

Chapter two gives a review of key literature relevant to this study in both empirical

and theoretical aspects. The research methodology and design are then explained in

the third chapter. Chapter four deals with analysis of the data collected while chapter

five gives the findings, summary, study review and recommendations that arise from

18

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 Introduction

This section reviewed existing literature from previous research which expound more

on regional trade and integration. Theoretical literature analyzes theories on regional

integration, economic growth and trade liberalization. The theoretical models used to

explain the said concerns are discussed with a view of giving crucial hints necessary

in understanding more about regional integration and economic growth in East Africa.

Empirical literature review centers on previous research findings and the methodology

that was used in establishing certain facts about the variables of concern.

2.2 Theoretical Literature

2.2.1 Trade Theories

There exist several theories that major their concerns on the subject of international

trade. These include the comparative advantage theory, absolute advantage theory,

factor proportions theory and new trade theory among others (Ranzau, 2009). Thus

these theories can be used as reference points in advancing arguments for or against

regional trade integration.

However, only two theories on international trade can be used to explain regional

integration. These are the Customs Union theory of trade creation and the Ricardian

theory of comparative advantage. Regional integration borrows heavily from these

two theories thus making them key points of reference.

2.2.1.1 Comparative Advantage Theory

The comparative advantage theory encourages countries to produce goods with low

19

argues that countries should channel their resources in production of goods where they

are more efficient and import where they are less efficient. This theory therefore

suggests that economic agents should compare opportunity costs involved in the

production of goods across countries rather than the monetary costs involved (Ranzau,

2009). The EAC member countries primarily deal with the same products i.e.

agricultural goods and import mainly machinery from developed countries since they

have same resource endowments. Thus, comparative advantage theory would not

adequately address intra-regional trade due to limited efficiency gains which could

lead to trade diversion.

2.2.1.2 The Customs Union Theory

On the other hand, the Customs Union theory as advanced by Jacob Viner (1950)

argues tariffs on trade between member states of a customs union should be lowered,

and a joint tariff be imposed on all imports from non-member states. This then results

in two outcomes namely trade creation and trade diversion. Trade creation occurs

when economic agents shift from domestic production with high costs to low cost

production in other member states within the customs union. Trade diversion then

occurs in cases where member states have to shift from low-cost external production

to high-cost production among member states of the customs union. Therefore, trade

creation improves welfare and the complete opposite happens in the case of trade

diversion.

2.2.1.3 The Modern Theories of Trade

Gravity model and the CGE (Computable General Equilibrium) model are also used

20

The Gravity model has managed to predict trade patterns for goods and services

between various countries. It argues that trade arrangements between two countries

occur as a result of the respective sizes of the two economies involved and the

distance between them. A gravity relationship, therefore, occurs in the sense that trade

costs increase with the distance between the two countries involved in trade. This

theory has been instrumental in the identification of the drivers behind mutual trade

flows e.g. common currencies and common borders. Many economic policies have

been formulated based on the use of gravity models which are very popular due to

their suitability in making empirical conclusions (H.L. David, 2007). However,

standard gravity factors address only two-thirds of the global trade (Ciuriak and Kinjo,

n.d). Thus, this makes the gravity theory unattractive for the one-third of the global

trade which may be relevant for this study.

The Computable General Equilibrium models also called the AGE (Applied General

Equilibrium) models are economic models used to estimate how economies of

countries involved in trade agreements can adjust to changes in technology and other

external factors that affect trade. CGE models borrow from input-output models,

models for planning for developing countries and also models used in economic

planning for richer countries. They assist policymakers to detect the economic impacts

of a change of one section of the economy upon the rest. Currently, one of the most

popular CGE models is the GTAP model of world trade which has been used in many

countries in economic growth planning. Such models are instrumental in economic

planning especially in instances where the relevant economies lack reliable data used

in analysis. General equilibrium models have been used in some literature reviews to

21

laid strict emphasis on macroeconomic factors that predict income gains in the context

of economies under integration agreements. However, some economists still insist that

regional integration impedes growth to a reasonable extent through trade diversion

(Grossman & Helpman, 1997).

2.2.2 Growth Theories

Endogenous growth theory and the Solow model are perfect economic models that

relate to international trade liberalization.

2.2.2.1 Neoclassical Growth Theories

The Solow model argues that long-term economic growth in any economy can only be

achieved through technological progress (Solow 1956). The theory further states that

poor countries can only catch up with other rich countries if the savings rate for

human capital and physical capital are the same.

According to the neoclassical growth theory, steady economic growth can only be

attained through a proper balance of the amounts of capital and labor in the production

technology in use (Njoroge, 2010). This means growth is achieved through exogenous

technological progress and labor increase. However, other economic theories have

argued that growth is driven by knowledge accumulation thus making technological

progress an exogenous variable and not exogenous as implied by earlier economists.

2.2.2.2 Endogenous Growth Theory

The Endogenous growth theory postulates that economic growth is determined by

endogenous factors within an economy rather than exogenous factors. The theory,

therefore, encourages economies to embrace competitive and innovative economic

22

2.2.3 Relationship between Trade and Economic Growth

Economic growth is affected by trade in a number of ways. To begin with, exchange

of knowledge in research and development issues occurs as a result of trade. In this

way, new innovations are shared among trading partners and this eventually leads to

economic growth (Barro, 2007).

Secondly, competition increases in the local market due to higher trade openness

thereby improving on productivity and which results to growth (Waziarg, 2004).

Dollar and Kraay, (2003) argue that countries with more trade flows with a high

degree of market liberalization tend to register high growth rates evidenced in their

high GDP per capita. Counter arguments to that view have however been raised by

some scholars who hold the view that market openness adversely affects economic

growth through erosion of competitive advantage, abuse of comparative advantage

and exposure to increased competition among other reasons. Some confusing results

have also risen from previous research. For example, membership of the European

Union was found to have no growth effects on constituent member states Landau,

(1996). In some other research, Henrickson established that membership in the same

union produced a long-term growth force ranging between 0.6 percent and 1.3 percent

per annum. Such significant differences have however been attributed to the poor

correlation between market liberalization process and the variables of concern.

Thirdly, many countries have experienced increased economic growth as a result of

trade widening of markets for their goods. On the contrary, economies restricted to

smaller markets have continued to register small economic growth rates (Alcala,

23

Fourthly, participation in international trade allows countries to adopt prudent

economic policies that cater for internal interests. These policies are founded on stable

macroeconomic foundations that allow the accumulation and increase of various

factors of production e.g. capital within an economy. In the long run, these economies

achieve high levels of growth which can only be traced back to engagement in

international trade agreements. Generally, increased exposure to trade serves as a

good catalyst of growth as evidenced in a number of economies. This view is further

supported by Aryeetey and Oduro (1996), Lyakurwa (1997) and Gunning (2001) who

attribute the rising economic growth rate of many countries in Africa to the existence

of strong regional trade agreements being experienced in the continent and which

thrive on a stable foundation of trade reforms and sound policies.

Integration helps countries achieve many benefits. For instance, agreements for

regional integration widens up markets for goods and services thus allowing

companies and industries to access a bigger market. Such arrangements enable

economies to take advantage of economies of scale thereby leading to accelerated

growth. Integration also accelerates trade across inter-country borders with the result

being increased monetary gains to the countries involved (Abraham Knife, 2005).

However, economic theory has not been able to determine whether the economic

benefits of integration are short term or can be sustained in the long term. This,

therefore, leaves a gap that requires empirical work to ascertain the truth of the matter.

2.3 Empirical Literature

While analyzing UDEAC, EU, CACM and ASEAN trade blocs, Vamvakidis (1998)

established that the EU registered some improved trade among its member countries

24

He, therefore, concluded that engagement in regional trade stimulated economic

growth in many countries and that varying rates of growth among countries in the

same trade bloc has no effect on the level of growth in any economy.

Frankel and Romer (1999) in the study ‘Does Trade Cause Growth?’ covered 150

countries in the penn World Table. The study estimated cross-country regressions of

income per person on international trade and country size suing instrumental variables

and compared the results with ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates from the same

equation. The study established that regional trade and income are positively

connected in that as trade increases the level of GDP, the income received by an

individual person in that economy also increases. This happens through the

accumulation of factor inputs such as human and physical capital.

Bassanini et al (2001) in the study “Economic Growth: The Role of Policies and

Institutions” used cross-country time-series regressions on OECD countries for the

period 1971 to 1998. The study aimed at establishing links between policy settings,

institutions and economic growth in OECD countries. According to this study, the

growth experienced in many developing countries in the past decades has been as a

result of human capital improvements. This has also been the case in other developed

nations such as Netherlands and Germany. The study established that accumulation of

factors of production in an economy was a key determinant of growth. Further, the

study pointed out that with increase in human and physical capital levels any economy

was destined to determine a considerable amount of growth.

The Global Economic Prospects report of 2005 showed that countries within trade

25

independently. Trade volumes were also noted to increase faster than economic

growth in the international arena for countries within trade agreements. Such

outcomes, therefore, prove that regional integration cannot be ignored in its role of

accelerating economic growth. International trade by way of easing the flow of

resources across borders and opening up of new markets ends up increasing growth. It

also reduces the cost of production as countries within the same regional trade

agreement access wider market with minimal transaction costs.

Innwon (2006) postulated that the East Asian Regional Trade Agreement would

positively impact the welfare of its member countries. The study used a CGE model to

evaluate the impact of various variables on growth and realized that regionalism

enhanced growth over time especially in cases where the trade agreement adopts an

expansionary policy whereby members cooperate with each other. This would not be

achieved in the event the countries competed with each other. Also, higher economic

and welfare gains were seen to accrue to original members of all regional trade

agreements. Further, additional trade benefits were seen to accrue for original

members despite all gains being unevenly distributed across the regional trade

arrangements.

Wooster (2007) conducted a study investigating the impacts of regional trade on

economic growth among European countries. The study focused on thirteen European

Union member countries and employed time-series regressions to analyze

inter-country data. The study found out that liberalization of trade was an important

stimulator of growth alongside population growth and Investment growth. Moreover,

it concluded that trade between members of the European Union with other

26

countries in all the countries that were under consideration. The study used real

economic variables in the study and was successful in distinguishing growth effects

arising from intra-regional trade from those of extra-regional trade. The study revealed

that extra-regional trade was more beneficial to an economy than trade among

members of one trade bloc. The study concluded that increased exposure to wider

markets witnessed when a country traded with members outside its trade bloc gave

that specific country a competitive advantage in terms of trade and this ended up

translating into higher growth rates. The competitive edge came about from the

tapping of new knowledge and skills from a variety of regions with such exchanges

only possible by way of extra-regional trade. This study borrows on the approach

where regional trade was split into the two identified categories in order to assess the

contribution of each to economic growth.

Willem (2008) researched about how convergence and growth come about as a result

of regional integration. He used standard growth models tested and proven true in

nearly 100 developing countries from Africa, Latin America and Asia for the period

1970 to 2004. His study failed to conclude whether regional integration results to

permanent economic growth effects. The study, however, did indicate that foreign

direct investments and trade promote growth to a vast extent. As such, since regional

integration increases the levels of foreign direct investments and trade, the study noted

that regional integration indirectly promoted the economic growth of many countries.

Reduction of intra-regional tariffs by lowering the price of imported goods from the

region leads to increased trade which in turn sets the conditions for growth. However,

the reduction achieves minimal impacts if the degree of trade between members of the

27

of income disparities among nations in the same trade arrangement. Integration also

helps countries to approach infrastructural projects that are key contributors to

economic growth in a bipartisan way that reduces costs and enhances efficiency of the

whole process. The study proposed further growth analytical work to be undertaken

which combines the development of methods to examine the effects of regions and

measurement of the various types of regional integration.

Empirical evidence sourced from SADC, COMESA and the EAC trade blocs on a

study about how regional integration impacts economic growth showed that the

relationship between the two main variables of interest can only originate from the

production function Njoroge (2010). In this study, a regional integration index was

constructed using the average tariff rates between countries in trade blocs and the

degree of cooperation in existence covering the period 1970 to 2008. The economic

index helped capture trade reforms within individual member states that came about as

a result of the integration. The index then captured trade reforms instituted by the

regional trade blocs as a whole towards the rest of the world. The study further

constructed a classification scheme combining tariff reduction measures on imports

necessary for deepening the cooperation among the countries involved. The analysis

of the study provided some alternative policy combinations that can be employed by

individual member countries within the selected regional trade blocs towards the

achievement of economic growth. Njoroge (2010) established a positive correlation

between economic growth and regional integration. The study confirmed that both

trade and economic integration have a positive impact on growth whether analyzed

28

for the comparison of the degree of integration across trade blocs and therefore does

not suit the study of a single regional block like is the case with this study.

Another study was carried out in Asia to ascertain the impact of both intra-regional

and extra-regional trade on the economic growth of nations. The study by Younes

(2010) assessed whether trade among member countries (intra-regional trade)

contributed more to output growth than trade with nonmember countries

(extra-regional trade) in thirteen Arab countries for the period 1990 to 2007. The study used

a standard growth model with trade intensities as focus variables besides running

granger causality tests for the trade-growth relationship. The empirical results

established that intra-regional trade was better in encouraging growth than

extra-regional trade.

Ouma (2015), in this study “Agricultural Trade and Economic Growth In East African

Community, 2000 – 2012” investigated the causes of intra-EAC agricultural sector

trade and cooperation, effect of EAC regional trade agreement on the regions

agricultural trade by analyzing the degree of trade creation and diversion effects. The

study decomposed trade and concentrated on agricultural trade. It employed panel data

approach using data between 2000 and 2012. Different panels for all the five EAC

countries were formed. The study applied the Pseudo Poisson Maximum Likelihood

which is considered relatively new and superior approach of estimation to gravity

model though it has not been applied in any earlier study in the region, and used the

bootstrap method to correct for heteroskedasticity. The study established that the

causes of intra-EAC agricultural exports, the effect of EAC regional agreement on the region’s agricultural exports, and the underlying connection between the agricultural

29

determinants of bilateral trade proposed by the modern theories of trade do have

different effects on trade volumes in different nations. The study confirmed a positive

correlation between increased agricultural exports and economic growth in some

countries, no correlation in others and still negative correlation in few others.

Agricultural exports also have a positive effect, no effect and negative impacts on

growth in different countries. This study is different from Ouma (2015) in that it used

aggregate trade but decomposed it into extra-regional and intra-regional trade.

However, it borrows from Ouma (2015) panel data approach with data between 2001

and 2014. The study then adopts standard neoclassical models to determine the

existing relationships between the variables of interest.

2.4 Overview of Literature

This research was intended to establish the contribution of regional trade on the

economic growth of the EAC member states.

This study borrowed from the works of Wooster (2007) and Younes (2010) by using

real economic variables and splitting regional trade into intra-regional and

extra-regional trade in achieving the study objectives. Their study covered European and

Arab countries respectively while this study took to East Africa Community to

establish the link between regional trade and economic growth. It borrowed on

Bassanis (2001) by incorporating human capital as a key factor of production.

This study applied panel data approach as used in Ouma (2015) but did not segregate

30

CHAPTER 3

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 3.1 Introduction

This chapter presents the methodology that was employed in this study. It entails the

research design, theoretical framework, empirical model, definition and measurement

of variables, data sources and data analysis.

3.2 Research Design

This research sought to unravel the impacts of trade within a regional setup on the

economic growth of countries within East Africa. The research design is

non-experimental panel study. The research used data recorded between years 2001 and

2014. The collected data was analyzed using cross-country time-series regressions

after undergoing time series property tests. Panel data analysis was adopted in this

study because of the sample size and the data used is cross-sectional. Besides, the

econometric analysis allows short-term adjustments and convergence speeds to vary

across countries while imposing (and testing) restrictions only on long-run

coefficients.

3.3 Theoretical Framework

The neoclassical growth theory is adopted for this research. A constant return to scale

production function as modeled by neoclassical economists was employed in this

study. Four variables are the focus of this model: Technology (A), Labor (L), Capital

(L) and Output (Y). According to the neoclassical economists production will not

occur unless some amount of these four variables are combined. Equation (3.1) shows

the functional form of the production function:

31

It should be noted that A and L enter multiplicatively in this production function and

the model assumes constant returns to scale. It should be noted that A is exogenously

determined and that AL represents effective labour. This study follows the standard

neoclassical growth model, employed by Mankiw (1993), which is derived from

constant returns to scale production function with labor and capital as the inputs which

are paid at their marginal products to arrive at an augmented Solow model in (3.2) by

allowing equation (3.1) to be further expressed as follows, with production at time t:

……….…… [3.2]

Where:

β represents partial output elasticity with respect to human capital (H).

H represents human capital.

L represents labour.

Y represents output.

K represents physical capital.

α represents partial output elasticity with regards to physical capital (K).

A (t) shows the level of efficiency with respect to technology.

The equations below give the time paths of the identified variables.

To arrive at the marginal products of the respective factor inputs we get the derivative

of the factor input with respect to time t assuming technology is constant. It should be

noted that the variables with dot marks represent derivatives of the original variables.

We now have the Solow-Swan Model by transforming equation (3.2) into a

differential equation as follows:

32

……… [3.3]

Whereby k represents K/L the ratio of capital to labor

y represents Y/L the individual output of a worker

h represents H/L average number of human capital

The rate of investment in physical capital is given by sk while rate of investment in

human capital is denoted by sh.

g represents the rate of change in technological progress while n indicates the labor

growth rate. The depreciation rate is denoted by d.

Equilibrium values ie k* and h* are determined after solving the available system of equations. Assume that α+β<1

…… [3.4]

If we substitute equation 3.3 into equation 3.1, we can determine the equilibrium by

use of logarithms. This new equation can be written in terms of human capital

investment or in the form of equilibrium value of human capital along with other

constituent variables. Given that this research values human capital using literacy

33

The equilibrium output level can be expressed as:

+ ……… [3.5]

The above equation only holds under assumptions that dependent variables remain

stable over time. Where this assumption is not adhered to, the expression ln (d+n+g) is

complemented with an equivalent rate of change to cater for the ensuing instability.

The resulting equation is then linearized and expressed in the simplest way possible.

Solving the differential equations arising from equations 3.1 and 3.2 however gives an

equilibrium level of human capital in actual terms. To be precise the specified

equations (having made growth rates the subject of the equations) can be substituted

into equation 3.3. The ensuing investment rates are then substituted out to give the

following equation.

α

……… [3.6]

Linearizing this equation helps us solve the expression for ln h

……… [3.7]

In this case

ѱ Represents a funtion of (d+n+g) and (α) & (β)

If equation 3.6 is rearranged to solve the value of ln h we get the following expression

Ln h* (t) = lnh(t) + (1-ѱ)/ѱ∆ ln (h(t)/A(t))

34

The equilibrium value of human capital cannot be ascertained even now

We therefore substitute equation 3.7 (giving the expression for ln h) into equation 3.4

in a bid to determine the actual value of equilibrium human capital values with respect

to investment and stock of human capital.

As noted in the literature review the resulting equilibrium equation can only hold if

the east African countries which are under study are always in a state of equilibrium

without any form of economic disturbances. Given the recorded growth rates in East

Africa were captured with no considerations to economic stability the model needed to

be adjusted to suit the transitional changes that happened. As a result, the temporary

dynamics can be expressed in linear form as:

.……… [3.9]

Given that λ is equivalent to (1-α-β) (g(t) + n(t) +d)

Solving the above equation gives us:

……… [3.10]

Given that

Expressing equation 3.9 in terms of h* and y* like is the case with equations 3.4 and

3.7 results to:

) ln α αlng+nt+d+ g

A 0 )gt…………... . [3.11]

The above equation holds under the assumption that the rate of technological progress

35

In special case scenarios where variable g cannot be observed, the indicators of this

variable can be distinguished from other constants by use of empirical methods. The

output equation by estimation can then be given as:

–

( )……… [3.12]

The above equation 3.11 can be used to estimate values for all time intervals. Large

time intervals such as 10 year periods lead to loss of key observations and therefore to

overcome such inefficiency, this study will employ single year time spans. Given the

high likelihood of annual data to contain unstable temporary components, such

shortcomings can be overcome by use of short run regressors. The equation can then

be expressed in a new form assuming the equilibrium condition for error correction

i.e. 1 < - (1- еλt) < 0)

b2 lnht+b3 lnn(t)+ɛ ………...……… [3.13]

The growth of GDP per capita according to literature review is a tool for estimating

regressions in growth.

We can therefore use the annual data available pooled across different countries and

then expressed in a time series form. The equilibrium output equation then becomes:

am+1, it+b1, i lnsi, tK+ b2, i lnhi, t+b3, i ni, t+ j=4mbj, ilnVi, t j+εi,

t………. [3.14]