Medical

Management

of Congenital

Nasolacrimal

Duct

Obstruction

Leonard

B. Nelson,

MD, Joseph

H. Calhoun,

MD, and

Hyman

Menduke,

PhD

From the Department of Pediatric Ophthalmology, Wills Eye Hospital and Department of Pharmacology, Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia

ABSTRACT. A consecutive series of 113 infants seen with congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction were treated with local massage and topical antibiotic ointment. In 107 of the infants the obstruction was resolved within 8 months of initiation of this form of management. Nearly all of the infants were spared a surgical procedure that probably would have been performed if early probing of the nasolacrimal system had been advocated. Pediatrics

1985;76:172-175; duct obstruction, nasolacrimal duct

ob-struction.

The most common abnormality of the infant’s lacrimal apparatus is congenital obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct.’ An imperforate membrane at the distal end of the nasolacrimal duct is the usual cause of occlusion.2’3 Estimates of the incidence of this condition in newborn infants range between 1.75% and

The infant with a nasolacrimal duct obstruction usually is initially seen within the first few weeks of life with the complaints of persistent tearing (epiphora) and crusting on the eyelashes. Typically, the tears spill over the lower lid and there is a wet look in the involved eye(s). This condition is differ-entiated from conjunctivitis by absence of conjunc-tival infection, history of chronicity, and epiphora without signs of a sensation of foreign body (ie, closing the involved eye). The diagnosis of nasola-crimal duct obstruction can also be confirmed in many cases by gently pressing over the nasolacrimal sac and observing mucopurulent material refluxing from either punctum. There is no sex difference or

Received for publication Feb 21, 1984; accepted Sept 24, 1984 Reprint requests to (L.B.N.) Wills Eye Hospital, Department of Pediatric Ophthalmology, 9th and Walnut Sts, Philadelphia, PA

19107.

PEDIATRICS (ISSN 0031 4005). Copyright © 1985 by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

preference for either eye in this condition.

Controversy has existed regarding the natural course and proper management of congenital na-solacrimal duct obstructions. Petersen and Robb6 stated that, in general, pediatricians advise waiting until it is evident that the problem will not spon-taneously resolve before recommending a naso-lacrimal probing. Jones and Wobrig7 and Ffooks8 recommended early probing of the nasolacrimal system after only several weeks of topical antibiotic therapy. Ffooks9 suggested that lacrimal abscess formation may result from delaying surgical treat-ment.

There is also disagreement concerning the type of medical management of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction prior to probing. Weil’#{176}advised against nasolacrimal system massage because it might cause pericystitis. Jones and Wobrig7 advo-cated only mild pressure over the nasolacrimal sac to express pus from the puncta without causing enough pressure to open the blocked nasolacrimal duct. Crigler” described a technique of applying pressure over the nasolacrimal sac to increase the hydrostatic pressure within the sac to attempt to rupture the membranous obstruction at the distal end of the nasolacrimal duct. Kushner’2 found that the need for probing was decreased after using the Crigler technique in a group of infants with naso-lacrimal duct obstruction when compared with find-ings in similar groups who received no treatment or only gentle massage.

The purpose of our study was to establish the rate of resolution of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. with medical management consisting

of massage and, when indicated, antibiotic oint-ment.

METHOD

.

Fig I. Top, technique of hydrostatic nasolacrimal mas-sage. Index finger is placed over nasolacrimal sac and pressure is exerted downward. Bottom, Downward pres-sure may cause rupture of membranous obstruction at bottom of nasolacrimal sac. (Reproduced with permission from Kushner.’2)

ARTICLES

173

months of age with congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction as evidenced by epiphora, noninflamed conjunctiva, recurrent mucopurulent discharge, and an otherwise normal ocular examination by one of the authors (L.B.N. and J.H.C.), were entered into a study to determine the effect of medical manage-ment. These patients were recruited sequentially from the practices of two of the authors (L.B.N. and J.H.C.), the Children’s Eye Clinic of Wills Eye Hospital, and as a result of a letter to local pedia-tricians requesting patients for this study. Infants with acute dacryocystitis, congenital mucocele of the nasolacrimal sac, history of trauma to the na-solacrimal system, or multiple congenital anomalies were excluded from this series.

Parents of the infants were instructed to massage the nasolacrimal system in a manner similar to that described by Crigler.” One of the authors (L.B.N. or J.H.C.) demonstrated the technique to the par-ents; it consisted of placing the index finger over the common canaliculus to block the exit of mate-rial through the puncta and stroking downward firmly to increase hydrostatic pressure within the nasolacrimal sac (Fig 1). One ofthe authors (L.B.N.

or J.H.C.) observed while the parents performed the massage technique. The parents were instructed to perform this maneuver for about five strokes twice a day. Erythromycin ophthalmic ointment was prescribed and was to be used twice a day when a mucopurulent discharge was present. All infants were treated with the above protocol until the symptoms and signs of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction resolved or the infant reached 13 months of age; at the beginning of this study, it was decided to continue this regimen until 13 months of age. This delay in probing was suggested by our “clinical impression” that most nasolacrimal duct obstructions resolve with medical treatment. After 13 months of age, a probing of the nasolacrimal system was advised.

Parents were telephoned monthly by one of the authors (L.B.N.) who asked whether the symptoms had resolved. If the parent, usually the mother, was in doubt, the infant was examined.

Of the 1 13 infants in the study, 48 were male and 65 were female. This sex difference does not differ significantly from a 50-50 distribution (P > .1).

Ages at initial examination by one of the authors (L.B.N. or J.H.C.) ranged from 1 to 10 months; the median age was 5 months and more than three fourths were between 2 and 7 months old.

In 35 infants, there was bilateral involvement, in 31 only the right eye was affected, and in 47 only the left eye was affected. This difference between 31 and 47 did not differ significantly from a 50-50 distribution (P > .05). In nearly all instances of bilateral involvement, resolution in one eye was within 1 week of resolution in the other. In three instances, there was a greater difference in the time of resolution, but in no instance did it exceed 2 months. For purposes of analysis in these patients, the longer time was used.

1.

RESULTS

The nasolacrimal duct obstructions had resolved in 107 of the 113 children within 8 months of initiating the noninvasive treatment described above. Two of the infants were 14 months old at the time of resolution (one had initially been seen at 8 months and the other at 10 months). Use of this regimen did not achieve resolution of the na-solacrimal duct obstruction in only six infants. In all six, probing was carried out between ages 14 to

19

months; duration of nonsurgical management was 4 to 9 months. One of the six infants required a second probing (at 18 months of age) before the obstruction was resolved. The median time to res-olution was 2 months from instituting medicalman-. agement; nearly three fourths of the patients

achieved successful resolution within 3 months of nonsurgical treatment. The overall success rate

by guest on September 7, 2020

www.aappublications.org/news

PROS$NSlQI1D( f f f ‘f

S

7

zS

P

F

2

I

4

MONTHS OF’ TREAThIBIT ctxcwwt 0, P*ONG)

Fig 2. Cumulative percent of infants with nasolacrimal duct obstruction that resolved with medical treatment by months of treatment.

with this form of management was 94.7% with 95% confidence limits of 88.7% to 98.0%. Cumulative percentages of successful resolution by months of treatment are presented in Fig 2.

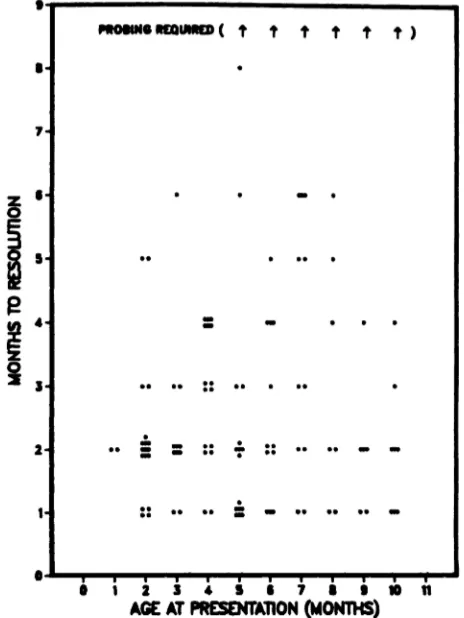

Data relating months of required treatment to age at presentation are shown in Fig 3. It seems apparent that, in cases in which resolution was not achieved, the duration’ of required treatment showed no observable relationship to age at pres-entation. However, all six infants in whom probing was required were at or above the median age of 5 months at presentation. The infant who required a second probing was 9 months old at presentation, among the oldest of the group.

Typically, the resolution of symptoms and signs occurred within a few days of instituting treatment. Parents became aware rather dramatically that their infant had no further evidence of epiphora or mucopurulent discharge. Usually, the time of reso-lution could be pinpointed to a particular week.

Some parents were disturbed by the appearance of the affected eye and were concerned that the infant would be uncomfortable as long as the tear-ing and matter were present. The parents were

pleased, however, when their infant’s nasolacrimal

a

i 2 3 4 5 S 7 1un

AGEAT PRESENTA11ON (MONTHS)

Fig 3. Months to resolution with medical treatment for

113 infants with congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruc-tion.

duct obstruction resolved without the need for a surgical procedure. In those few instances in which probing was required, the success of the operation did not seem to have been jeopardized by the delay.

Although no attempt was made to test the par-ents’ compliance, the authors (L.B.N. and J.H.C.) did observe them perform the massage technique. Even if some of the parents did not massage or performed it incorrectly, 94.7% of the nasolacrimal duct obstructions resolved without the trauma, cost, and risk of surgical invasion.

DISCUSSION

ARTICLES

175

Pollard’3 found that resolution was achieved in 41 of 100 infants with a nasolacrimal duct obstruc-tion who were followed conservatively in the first 6 months of life. Pollard recommended probing in-fants after the age of 6 months. He did not, however, describe his massage technique.

Crigler” reported a 100% success rate with his massage technique during a 7-year period, but he did not indicate the size of his clinical series. In a series of 203 cases of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction, Price’4 reported a 94.6% cure rate by

1 year of age using a technique of nasolacrimal system massage similar to that of Crigler.

Kushner’2 divided 132 infants with 175 affected eyes into three groups; the average age at the time of their initial examination was approximately 7 months. All infants were treated for 1 month or until 6 months of age, whichever came later, at which time a probing was performed. Data were reported in terms of eyes rather than patients. There was no observable difference between those who did not receive massage and those given gentle massage; 8% ofthe 116 affected eyes in these groups showed improvement. Of 59 affected eyes for which the Crigler technique of massage was used, 31% showed improvement.

Some ophthalmologists’5”6 have expressed con-cern that the longer the delay beyond 2 to 4 months after birth, the poorer the results of probing naso-lacrimal duct obstructions. In our consecutive series of 113 infants with nasolacrimal duct obstructions, 107 obstructions resolved by the eighth month of medical management. Approximately 95% of the patients were spared a surgical procedure that prob-ably would have been performed if earlier probing had been advocated. Nearly three fourths of the nasolacrimal duct obstructions had resolved after 3 months of noninvasive treatment; there seemed to be no relationship to age at presentation. Although Kushner’2 found, as we did, that the technique of applying digital pressure over the nasolacrimal sys-tern was highly successful, he treated many of his patients for only 1 month after which he probed the infants with unresolved nasolacrirnal duct oh-structions.

The patients entered this study at random, based on their primary care physician’s decision to refer them. The infants’ median age at presentation was 5 months, thus our study population is presumably biased, if at all, in the direction of infants who did not experience spontaneous, early resolution of their nasolacrirnal duct obstructions. Therefore, the rate of resolution, either spontaneous or by

nonin-vasive management, is undoubtedly higher than the figures of this study indicate.

Based on this study, the authors recommend that all infants less than 13 months of age with uncom-plicated congenital nasolacrimal obstructions be treated with digital massage as described under “Methods,” and with topical erythromycin oint-ment used twice daily if any mucopurulent dis-charge is present. The majority of obstructions will resolve by age 13 months, and probing of the na-solacrimal system will not be required. Further investigation is needed to determine the rate of the resolution of nasolacrimal duct obstructions after 13 months of age.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was made possible, in part, by a grant from Fight for Sight mc, New York, to the Fight for Sight Children’s Eye Center of the Wills Eye Hospital.

The authors thank the many pediatricians from Phil-adelphia and the surrounding areas who referred the patients for this study.

REFERENCES

1. Nelson LB: Pediatric Ophthalmology. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1984

2. Cassady JV: Developmental anatomy of nasolacrimal duct.

Arch Ophthalmol 1952;47:141-158

3. Sevel D: Development and congenital abnormalities of the nasolacrimal apparatus. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabi.smus

1981;18:13-19

4. Cassady TC: Dacryocystitis in infancy. Am J Ophthalmol 1948;31:773-780

5. Guerry D, Kendy EL: Congenital inpatency of the naso-lacrimal duct. Arch Ophthalmol 1948;39:193-204

6. Petersen RA, Robb RM: The natural course of congenital obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct. J Pediatr Ophthalmol

Strabismus 1978;15:246-250

7. Jones LT, Wobrig JL: Congenital anomalies of the lacrimal system, in Surgery of the Eyelids and Lacrimal System.

Birmingham, AL, Aesculapius, 1976, pp 163-167

8. Ffooks 00: Dacryocystitis in infancy. Br J Ophthalmol

1962;46:422-434

9. Ffooks 00: Lacrimal abscess in the newborn. Br J Ophthal-mol 1961;45:562-565

10. Weil BA: Acute dacryocystitis in the newborn infant, in Veirs ER (ed): The Lacrimal System. St Louis, CV Mosby, 1971, p 124

11. Crigler LW: The treatment of congenital dacryocystitis.

JAMA 1923;81:23-24

12. Kushner BJ: Congenital nasolacrimal system obstruction.

Arch Ophthalmol 1982;100:597-600

13. Pollard ZF: Tear duct obstruction in children. Clin Pediatr

1979;18:487-490

14. Price H: Dacryostenosis. J Pediatr 1947;30:300-305

15. Katowitz JA: Lacrimal drainage surgery, in Duane TD, Jaeger EA (eds): Clinical Ophthalmology. Philadelphia, JB Lippincott, 1984

16. Veirs ER: Disorders ofthe nasolacrimal apparatus in infants and children. J Pediatr Ophthalmol 1966;3:32-34

by guest on September 7, 2020

www.aappublications.org/news

1985;76;172

Pediatrics

Leonard B. Nelson, Joseph H. Calhoun and Hyman Menduke

Medical Management of Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/76/2/172

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or in its

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

1985;76;172

Pediatrics

Leonard B. Nelson, Joseph H. Calhoun and Hyman Menduke

Medical Management of Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/76/2/172

the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on

American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.

American Academy of Pediatrics, 345 Park Avenue, Itasca, Illinois, 60143. Copyright © 1985 by the

been published continuously since 1948. Pediatrics is owned, published, and trademarked by the

Pediatrics is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly publication, it has

by guest on September 7, 2020

www.aappublications.org/news