Procedural Pain in Children: A Randomized Trial

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: The most frequent cause of pain in children is diagnostic or therapeutic procedure–related pain. Inhalation of nitrous oxide in oxygen is a well-known effective analgesia, without major adverse effects and widely used in pediatric settings for minimally invasive procedures.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: We determined through a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical assay that nitrous oxide inhalation was notably more effective than placebo in decreasing pain by nearly half for minor pediatric procedures in patients aged 3 to 18 years.

abstract

OBJECTIVE:This randomized, single-dose, double-blind, Phase III study was designed to compare the level of procedural pain after use of premixed equimolar mixture of 50% oxygen and nitrous oxide (EMONO) or placebo (premixed 50% nitrogen and oxygen).

METHODS:Patients aged 1 to 18 years were randomly assigned to receive EMONO (n⫽52) or placebo (n⫽48) delivered by inhalation through a facial mask 3 minutes before cutaneous, muscle, or bone/ joint procedures. Pain was evaluated (on a scale from 0 –10) using a self-reported Faces Pain Scale–Revised (FPS-R) or a Spanish observa-tional pain scale (LLANTO). Rescue analgesia (with propofol or sevoflu-rane) was administered if pain scores were greater than or equal to 8. Collaboration, acceptance, ease of use and safety were evaluated by the attending nurse.

RESULTS:There were significant differences between the 2 groups (EMONO versus placebo) for both scales (mean values): LLANTO: 3.5 vs 6.7, respectively (P⫽.01) and FPS-R: 3.2 vs 6.6, respectively (P⫽.0003). Patients not receiving EMONO (P⫽.0208)—in particular those aged younger than 3 years (P⬍.0001)—required more rescue analgesia. There were also significant differences between the 2 groups (EMONO versus placebo) for adequate collaboration (80% vs 35%;P⬍.0001) and acceptance (73% vs 25%;P⬍.0001). Ease of use was not signifi-cantly different between groups (98.1% vs 95.8%;P ⬎ .05). Only 2 patients (in the EMONO group) presented with mild adverse events.

CONCLUSIONS:EMONO inhalation was well tolerated and had an esti-mated analgesic potency of 50%, and it is therefore suitable for minor pediatric procedures.Pediatrics2011;127:e1464–e1470

AUTHORS:Francisco Reinoso-Barbero, MD, PhD,a Samuel I. Pascual-Pascual, MD, PhD,bRaul de Lucas, MD,c Santos García, MD, PhD,bCatherine Billoët, MD,dViolaine Dequenne, PharmD,eand Peter Onody, PharmD, PhDe

aDepartment of Anaesthesiology,bDepartment of Paediatrics,

andcDepartment of Dermatology, University Hospital La Paz,

Madrid, Spain;dMedical Department, Air Liquide Santé

International, Paris, France; andeAir Liquide Medicinal, Madrid,

Spain

KEY WORDS

nitrous oxide, inhalatory administration, systemic analgesics, pediatric procedures, pain assessment, visual analog scale, observational pain scale

ABBREVIATIONS

EMONO—equimolar mixture of 50% oxygen and nitrous oxide rFPS—Faces Pain Scale–Revised

EMLA—eutectic mixture of local anesthetics

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2010-1142

doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1142

Accepted for publication Feb 8, 2011

Address correspondence to Francisco Reinoso-Barbero, MD, PhD, University Hospital La Paz, 265 Paseo de la Castellana, 28046 Madrid, Spain. E-mail: freinosob.hulp@salud.madrid.org

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright © 2011 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

During the course of a disease, chil-dren may have to undergo numerous invasive procedures. Indeed, in this population, the most frequent cause of pain is diagnostic or therapeutic procedure–related pain.1 The

conse-quences of a lack of appropriate anal-gesia during these procedures can ex-tend over a long period of time in a child’s life.2

Despite the use of local anesthesia or premedication, invasive procedures are still an unpleasant experience for the child. In addition to treating disease-related pain, the usefulness of managing procedure-related pain has become obvious. More specifically, there is a need for new and safe anal-gesic/sedative therapeutic methods that are, if possible, easy to adminis-ter. The premixed equimolar mixture of 50% oxygen and nitrous oxide inha-lation (EMONO), already indicated in the pediatric setting for conducting brief painful procedures, is a straight-forward, effective, and rapidly revers-ible analgesic method, without major adverse effects. This method is widely used in pediatric outpatient settings for minimally invasive procedures.3

The specific objective of the present study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of EMONO in various painful pro-cedures performed during pediatric practice in a hospital setting.

METHODS

Study Participants

The protocol was approved by the insti-tutional ethical board for human stud-ies at University Hospital La Paz, Ma-drid, Spain.

Written informed consent was ob-tained from all the parents, and assent was obtained from 6- to 18-year-old children and adolescents after careful explanation of the procedure by the physician in charge of the procedure. One hundred children from different pediatric services (emergency

depart-ment, dermatology departdepart-ment, pedi-atric pain unit, and neurology service) were enrolled in this prospective study, performed from January 2007 to April 2008. Patients were eligible if they were undergoing short diagnostic or therapeutic procedures on skin, muscles, or bones/joints. They were in-eligible if their general condition was impaired (American Society of Anes-thesiologists category⬎3), they were unable to rate pain on the Faces Pain Scale–Revised (rFPS), were not suit-able for scale evaluation using the Spanish version of an observational pain scale (LLANTO), had impaired con-sciousness, or if they presented with a contraindication to the use of nitrous oxide (hemodynamic instability, vita-min B12deficiency, intracranial hyper-tension, pneumothorax, or fractures of the facial bones). The patients were randomly assigned to inhale either EMONO (Kalinox; Air Liquide Santé In-ternational, Paris, France) or pre-mixed 50% nitrogen and oxygen (con-trol [placebo] group). The medical team was blinded to the mixture in-haled by the patient, and the patients were also unaware of the mixture used.

Procedure

All the procedures were performed in the pediatric pain unit or in the emer-gency department by pediatric derma-tologists, neurologists, or general pe-diatricians. All the patients were recruited on the basis of procedures that before this study had usually been performed without any specific sys-temic sedation or analgesia. Fasting is not necessary for EMONO administra-tion but was included in the trial de-sign in case general anesthesia be-came necessary.

According to the cutaneous procedure to be performed, some patients (eg, those scheduled for treatments of larger cutaneous lesions) were

pre-pared with the application of an eutec-tic mixture of local anestheeutec-tic (EMLA; APP Pharmaceuticals, LLC, Schaum-burg, IL) cream 1 hour before the pro-cedure. Patients scheduled for nevus excision, laceration repair, or skin bi-opsy received subcutaneous injections (through a 22-gauge needle) of mepi-vacaine (AstraZeneca Pharmaceuti-cals, Macclesfield, UK) 3 minutes after inhalation of the studied agents. Pa-tients scheduled for venous cannula-tion (22-gauge needle) did not receive any concomitant medication. Patients in the muscular group received only intramuscular botulinum toxin through a 22-gauge needle. Patients in the os-teoarticular group did not receive con-comitant medication for lumbar punc-ture (22-gauge needle), joint puncpunc-ture (22-gauge needle), or bone marrow as-piration needle insertion (20 gauge). The patients were transferred to the operating table accompanied by 1 of their parents and were not strapped to the table in any way. A pediatric-trained nurse and an auxiliary nurse assisted the physician in each proce-dure. Patients were continuously monitored with a pulse oximeter and electrocardiogram to fulfill the trial design protocol, and blood pressure was registered before and after each procedure.

The patients inhaled the premixed EMONO or placebo mixtures through a close-fitting scented face mask for 3 minutes before the procedure. Both treatments were packaged in identical B20 type cylinders under a 170 bar pressure providing the equivalent of 5.5 m3 of gas under a pressure of 1

nor the patients knew which gas mixture was contained in each cylinder. During the procedure, the patient inhaled the gas mixture continuously. The inhalation of the gas mixture was stopped when the physician ended the procedure. The pa-tient remained under observation in the operating room for at least 10 minutes under continuous cardiovascular and pulse oximetry monitoring.

Primary Outcome: Quality of Sedation and Pain Control

The primary outcomes for this study were quality of sedation and pain con-trol. These outcomes were evaluated by the patient in a self-reported as-sessment and/or by the procedure team using the observational pain scale LLANTO. Pain scores were re-corded before starting the procedure and immediately on termination of the procedure (ie, the reported moment for maximum expression of pain in children under conscious sedation).4

Patients 6 years of age and older were asked to report pain control using an rFPS. They rated the intensity of pain on the 6-interval scale, which repre-sents pain as 6 faces expressing differ-ent degrees of pain, from the left-hand side “no pain” first face to the last right-hand side “very painful” face.5

The patients were instructed to choose which of the 6 faces that indicated the magnitude of their pain in its position relative to the 2 extremes. The pain score was expressed in paired scores on a scale from 0 to 10.

Pain assessed with the LLANTO scale was rated by the procedure nurse be-fore and at the end of the procedure. The LLANTO scale6is a Spanish version

(“Llanto” is the Spanish word for cry-ing) of an observational scale that is a composite measure which addresses 5 behavioral items (crying, psycholog-ical attitude, respiratory pattern,

pos-can thus range from 0 to 10. This scale has been most frequently used in stud-ies investigating acute pain manage-ment under various circumstances in Spanish children.7,8

The primary outcome also includes the number of treatment failures with the blinded inhalation mixture. The procedure team decided consen-sually whether the procedure was to be continued with the experimental in-halation mixture alone. This decision was based on the pain expressed by the patient or assessed based on be-havioral changes by the patient during the procedure. In case of pain scores

ⱖ8, a deep sedation or light anesthe-sia was induced, taking advantage of the presence of an anesthesiologist/ intensivist in the procedure room, by using intravenous propofol (B. Braun Laboratories, Melsungen, Germany) (3– 4 mg/kg) or inhalatory sevofluo-rane (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) (4%– 6%).

Secondary Outcomes

After the completion of the procedure, the nurse rated cooperativeness on a 5-point behavioral scale (poor, fair, good, very good, or excellent). Accep-tance and ease of use with the blinded inhalation mixture were evaluated with yes or no responses.

Adverse Effects

Respiratory adverse effects such as desaturation, defined arbitrarily by pulse oximetric saturation ⱕ94% for

ⱖ30 seconds, symptomatic arterial hypotension, or bradycardia—as well as gastrointestinal adverse effects (nausea, vomiting) or the occurrence of unpleasant sensations—were eval-uated during and after the procedure.

Statistical Analysis

An independent statistician performed the analysis. Seventeen patients per

treatment group were needed to reach an 80% statistical power with an␣risk (2-sided) equal to 0.05. Patients were classified in 3 groups, depending on the type of procedure. Each patient was assigned to 1 of the 2 study groups. The choice of group was made by drawing lots. Patient assignment to a study group was performed in each hospital department. Fisher’s exact tests were used to test differences in the proportions of failures between the 2 study arms. In the case of quali-tative variables (rFPS and LLANTO), dif-ferences between the 2 study arms were tested with nonparametric Wil-coxon rank tests. All statistical analy-ses were performed with SAS 6.12 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

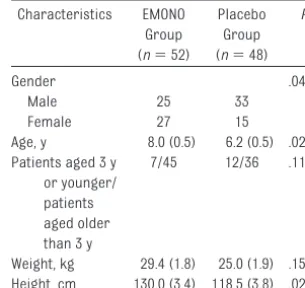

One hundred patients were included in the study. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were minimal differences in age, heart rate, and gen-der but not in weight, baseline blood pressure, pulse oximetry, or basal pain.

The characteristics of the proce-dures in each group are shown in Table 2. No differences were observed in the distribution of type of proce-dure, inspiratory flow, duration of pro-cedure, or in the use of concomitant topical anesthetic creams between the 2 groups.

Group (n⫽52)

Group (n⫽48)

Gender .0404

Male 25 33

Female 27 15

Age, y 8.0 (0.5) 6.2 (0.5) .0210 Patients aged 3 y

or younger/ patients aged older than 3 y

7/45 12/36 .1191

The pain reported by the patient (rFPS) or the LLANTO scores reported by the nurse just at the end of the procedure was significantly lower in the EMONO group (Fig 1). The pain scores (mean [SE]) were nearly 50% lower when EMONO was used alone (rFPS: 3.6 [3.3],

P⬍.0001; LLANTO: 4.6 [4.1],P⬍.0028) and nearly 80% lower with the con-comitant use of EMONO plus EMLA cream (rFPS: 1.2 [1.4], P ⬍ .001; LLANTO: 1.1 [1.6],P⬍.0029) compared with the placebo group without EMLA cream (rFPS: 7.4 [2.2]; LLANTO: 6.8 [4.2]).

Both scales were used in 23 patients, all of whom were close to 6 years old.

In addition to staff observations, these children also wanted to report their level of pain. A statistically significant correlation between the 2 scores was found in these 23 patients (r⫽0.556 [P⬍.0035]).

The rate of failure was significantly lower in the EMONO group compared with the control group (Table 2). Fail-ure was observed more frequently in patients younger than 3 years (14 of 19 patients) compared with patients older than 3 years (11 of 81 patients) in a statistically significant way (P ⬍

.0001).

The patients’ cooperation with the pro-cedure as assessed by the team

nurses was significantly greater (P⬍

.05) for patients in the EMONO group compared with patients in the control group (Fig 2).

Nurse acceptance was also signifi-cantly better for the EMONO group compared with the placebo group (75% vs 23%; P⫽ .001). Ease of use was considered very high in both groups (EMONO group: 98.1%; placebo group: 95.8%).

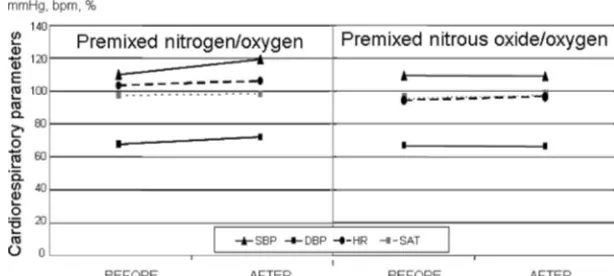

The tolerance of the gas mixtures was evaluated during and immediately af-ter the procedure. No cardiac or respi-ratory adverse effects were observed during the procedures in either group (Fig 3). Nausea and vomiting did not occur in any patient. Only 2 patients (both in the EMONO group) reported a very unpleasant sensation after expo-sure that motivated treatment with-drawal and delaying the procedure for a few minutes.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical assay to evaluate the potency of the analge-sic effects induced by inhalation of EMONO during minor painful proce-dures in the pediatric population. Pre-vious articles have reported the effi-cacy and safety of EMONO inhalation but all were retrospective studies,

co-TABLE 2 Characteristics of the Procedures in Both Treatment Groupsa

Characteristics EMONO Group (n⫽52)

Placebo Group (n⫽48)

P

Type of procedure .5650

Skin 25 22

Bone 9 10

Muscle 18 16

Concomitant treatmentb

10/42 7/41 .5369

Duration, min 9.2 (0.3) 9.7 (0.9) .5239 Flow rate, L/min 7.6 (0.3) 7.0 (0.3) .1912 Rescue anesthesiac 8/44 17/31 .0208

aData are expressed as number of patients or mean (SE). bConcomitant treatment consisted in EMLA cream application.

cRescue anesthesia consisted in administration of intra-venous propofol or inhaled sevofluorane.

FIGURE 1

Comparison of pain scores displayed by the children immediately before and at the end of the procedure. rFPS (A) results were self-reported in children older than 6 years of age. Observational LLANTO scale scores were assessed by the nurse (B) in younger children. Both scales were scored from 0 to 10. Data are plotted as mean (SE).aComparison of EMONO group versus placebo group,P⬍.05.

FIGURE 2

hort analyses, or randomized clinical trials, the latter using some other medication but not a placebo as the control.3,9–12In these studies, it is

pos-sible to identify some aspects of the effects of a treatment: relative effi-cacy,3clinical acceptance,9or clinical

utility.10 Some of these studies were

conducted in very specific circum-stances such as central venous canu-lation.11 However, these studies have

several drawbacks because they can-not distinguish the actual effect of EMONO from that of other added drugs that may have masked or intensified its real analgesic potency.12

Nevertheless, there are ethical ques-tions regarding randomized clinical assays in children, particularly the use of a placebo to control pain. For these reasons, although our study was an randomized clinical assay, Phase III study it included only those medical procedures that were usually con-ducted without any kind of analgesia/ sedation in our hospital. Unfortu-nately, some restrictions affect administration of effective anesthesia/ analgesia in a hospital outpatient set-ting (basically, medical consultation rooms that are far from the operating room or the critical care units where appropriate surveillance by

well-trained pediatric anesthesiology/criti-cal care physicians is assured). The patients included in the present study had the benefit of the involvement of an anesthesiologist or an intensivist dur-ing the procedure. Thus, if a patient expressed or showed severe pain (25% in the present study), it was pos-sible to administer deep sedation or a light general anesthesia instead of the usual physical restraint, indepen-dently of the group to which they were assigned.

The 2 study arms were similar in the type of procedure performed, the use of previous treatment (topical local an-esthetic creams), the intensity of pain experienced before the procedure, and in the quantity and duration of ad-ministration of the 2 gas mixtures. But, despite the fact that the study was ran-domized, a slight but statistically sig-nificant difference was found in the distribution of gender and age. The EMONO group had a majority of male patients but not the control group (69% vs 48%,P⬍.04). Also, patients receiving EMONO were slightly older than those in the control group (8.0 vs 6.2 years;P⬍.021). These small differ-ences were only minimally significant and do not seem to have had any clini-cal meaning because the degree of

co-is the same in boys and girls.13The

re-maining parameters included in the study, except for those depending on age such as height or heart rate (phys-iologically, heart rate decreases with age14), were exactly the same for the 2

groups; these parameters comprised concomitant medications, preproce-dural pain scores, and use of fresh gas flow.

The statistical analysis did strongly demonstrate that EMONO had a posi-tive effect on pediatric patients. The analgesic potency of EMONO was esti-mated as 51%, because, compared with placebo, pain levels were de-creased by half in the EMONO patients during and at the end of the proce-dures on both the self-report and the observational scale. With both kinds of scales, mean pain scores at the end of the procedure in the EMONO group ranged from 3.5 to 3.2 versus 6.7 to 6.6 in the control group (P⬍ .0003). This statistically significant difference means that, from a clinical point of view, most patients in the EMONO group experimented only slight pain while most patients in the control group suffered moderate pain. In addi-tion to this analgesic effect, there was a simultaneous anxiolytic effect, as re-flected by the above-mentioned coop-eration scale, which showed that pa-tients in the EMONO arm were twice as cooperative during the procedure.

The analgesic potency of EMONO was also confirmed by the limited need for supplementary rescue analgesia. In this context, only 15% of patients in the EMONO group needed rescue analge-sia compared with 35% of patients in the control group (P⬍.020).

Reviewing other medical articles that study the analgesic potency of differ-ent drugs and techniques in medical procedures similar to those studied in this article, it is possible to conclude

FIGURE 3

that the analgesia produced by EMONO is strong enough for these proce-dures. For instance, the use of non-pharmacologic treatments, such as oral sucrose or a pacifier, have demon-strated a very low potency, if any.15,16

Other nonpharmacologic measures, such as music therapy during painful procedures, have shown a slight anal-gesic potency ranging from 15% to 18%17(measured by decreases in the

doses of the required analgesic drugs). However, these nonpharmaco-logic measures seem to be more effec-tive in reducing anxiety than in alleviat-ing pain.18

Cooling the skin with a spray also has limited usefulness19because the

reduction in pain that it provides has been quantified as⬃19%. Other top-ical measures such as local anes-thetic creams (EMLA is the most used) or topical lidocaine alone have a calculated efficacy rate of 25% to 30%.20–22Therefore, EMONO is more

po-tent than all the topical measures. A

combination of EMLA cream and

EMONO has been proven to improve their respective efficacy in pediatric procedures such as intramuscular in-jections,20 as was confirmed in our

study; furthermore, it was calculated that EMLA cream enhances the analge-sia produced by EMONO alone by ⬃30%.

In this context, EMONO is safe. In our series, only 2 patients in the EMONO group presented a slight and brief wanted effect, consisting of an un-pleasant sensation of malaise. The ef-fect disappeared within a few minutes after discontinuing the drug.

Despite the fact that the need for res-cue analgesia decreased by nearly half with EMONO (Table 2), the only weak point we found regarding the use of EMONO in medical procedures with children was its reduced efficacy in younger children. In the present study, patients aged younger than 3 years needed more rescue analgesia than older children. This finding was con-firmed by a large observational multi-center study that had previously de-scribed how children younger than 3 years old under nitrous oxide analge-sia exhibited more crying and other in-appropriate behavior than the older children during invasive procedures.12

This finding is relatively new because most of the previous studies were per-formed in patients aged older than 6 years.10,23,24 Pharmacokinetic reasons

associated with very young children’s higher alveolar concentration require-ment could explain this lower po-tency.25Another explanation could be

that EMONO also presents euphoric and amnesic effects which could influ-ence self-reporting of pain at the end

of the procedure, especially in older children who can usually control their feelings of pain and even cooperate with the inhalation through the mask better in the absence of anxiety. This explanation could be confirmed by the fact that, as observed in Fig 1, younger children who were evaluated with the observational LLANTO scale showed higher pain scores both before and af-ter using EMONO.

Future studies will be needed to deter-mine if the intensity of the manipula-tion influences the efficacy of EMONO analgesia and whether this analgesic technique can be helpful in more pain-ful procedures such as thoracic tube removal.26

CONCLUSIONS

EMONO inhalation was well tolerated and had an estimated analgesic po-tency of 50%, and it is therefore suit-able for minor pediatric procedures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Air Liquide provided financial support for this study.

We acknowledge the following nurses for their essential support and ser-vices during the course of these stud-ies: M. M. Melo Villalba, C. Simon Gar-cia, and M. Pena Galeron. We also thank C. F. Warren for her linguistic assistance.

REFERENCES

1. Taylor EM, Boyer K, Campbell FA. Pain in hos-pitalized children: a prospective cross-sectional survey of pain prevalence, inten-sity, assessment and management in a Canadian pediatric teaching hospital.Pain Res Manag. 2008;13(1):25–32

2. Porter FL, Grunau RE, Anand KJ. Long-term effects of pain in infants.J Dev Behav Pedi-atr. 1999;20(4):253–261

3. Fauroux B, Onody P, Gall O, Tourniaire B, Ko-scielny S, Clément A. The efficacy of pre-mixed nitrous oxide and oxygen for fiberop-tic bronchoscopy in pediatric patients: a randomized, double-blind, controlled study.

Chest. 2004;125(1):315–321

4. Shapira J, Kupietzky A, Kadari A, Fuks AB,

Holan G. Comparison of oral midazolam with and without hydroxyzine in the seda-tion of pediatric dental patients.Pediatr Dent. 2004;26(6):492– 496

5. Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, van Korlaar I, Goodenough B. The Faces Pain Scale–Revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement.Pain. 2001; 93(2):173–183

6. Reinoso-Barbero F, Lahoz Ramón AI, Durán Fu-ente MP, Campo García G, Castro Parga LE. LLANTO scale: Spanish tool for measuring acure pain in preschool children [in Spanish].

An Pediatr (Barc). 2010;74(1):10 –14 7. Reinoso-Barbero F, Saavedra B, Hervilla S,

de Vicente J, Tabarés B, Gómez-Criado MS.

Lidocaine with fentanyl, compared to mor-phine, marginally improves postoperative epidural analgesia in children.Can J An-aesth. 2002;49(1):67–71

8. Reinoso-Barbero F, Martínez-García E, Hernández-Gancedo MC, Simon AM. The ef-fect of epidural bupivacaine on mainte-nance requirements of sevoflurane evalu-ated by bispectral index in children.Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2006;23(6):460 – 464 9. Lévêque C, Mikaeloff Y, Hamza J, Ponsot G.

Efficacy and safety of inhalation premixed nitrous oxide and oxygen for the manage-ment of procedural diagnostic pain in neu-ropediatrics [in French]. Arch Pediatr. 2002;9(9):907–912

procedures: a satisfaction survey.Paediatr Nurs. 2006;18(8):31–33

11. Abdelkefi A, Abdennebi YB, Mellouli F, et al. Effectiveness of fixed 50% nitrous oxide ox-ygen mixture and EMLA cream for insertion of central venous catheters in children. Pe-diatr Blood Cancer. 2004;43(7):777–779 12. Annequin D, Carbajal R, Chauvin P, Gall O,

Tourniaire B, Murat I. Fixed 50% nitrous oxide oxygen mixture for painful proce-dures: a French survey.Pediatrics. 2000; 105(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/ cgi/content/full/105/4/e47

13. Bishai R, Taddio A, Bar-Oz B, Freedman MH, Koren G. Relative efficacy of amethocaine gel and lidocaine-prilocaine cream for Port-a-Cath puncture in children. Pediatrics. 1999;104(3). Available at: www.pediatrics. org/cig/content/full/104/3/e31

14. Wallis LA, Healy M, Undy MB, Maconochie I. Age related reference ranges for respira-tion rate and heart rate from 4 to 16 years.

Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(11):1117–1121 15. Johnston CC, Filion F, Nuyt AM. Recorded

maternal voice for preterm neonates un-dergoing heel lance.Adv Neonatal Care. 2007;7(5):258 –266

crose and/or pacifier as analgesia for in-fants receiving venipuncture in a pediatric emergency department.BMC Pediatr. 2007; 7:27

17. Cepeda MS, Carr DB, Lau J, Alvarez H. Music for pain relief.Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006; (2):CD004843

18. Sinha M, Christopher NC, Fenn R, Reeves L. Evaluation of nonpharmacologic methods of pain and anxiety management for lacer-ation repair in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4): 1162–1168

19. Farion KJ, Splinter KL, Newhook K, Gaboury I, Splinter WM. The effect of vapocoolant spray on pain due to intravenous cannula-tion in children: a randomized controlled trial.CMAJ. 2008;179(1):31–36

20. Carbajal R, Biran V, Lenclen R, et al. EMLA cream and nitrous oxide to alleviate pain induced by palivizumab (Synagis) intramus-cular injections in infants and young chil-dren.Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):e1591. Avail-able at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/ 121/6/e1591

21. Zempsky WT, Bean-Lijewski J, Kauffman RE, et al. Needle-free powder lidocaine delivery system provides rapid effective analgesia

parison of Venipuncture and Venous Cannu-lation Pain After Fast- Onset Needle-Free Powder Lidocaine or Placebo treatment trial.Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):979 –987 22. Taddio A, Soin HK, Schuh S, Koren G, Scolnik

D. Liposomal lidocaine to improve proce-dural success rates and reduce proceproce-dural pain among children: a randomized con-trolled trial.CMAJ. 2005;172(13):1691–1695 23. Ekbom K, Jakobsson J, Marcus C. Nitrous oxide inhalation is a safe and effective way to facilitate procedures in paediatric outpa-tient departments.Arch Dis Child. 2005; 90(10):1073–1076

24. Hee HI, Goy RW, Ng AS. Effective reduction of anxiety and pain during venous cannulation in children: a comparison of analgesic effi-cacy conferred by nitrous oxide, EMLA and combination.Paediatr Anaesth. 2003;13(3): 210 –216

25. Eger EI 2nd. Age, minimum alveolar anaes-thetic concentration, and minimum alveo-lar anesthetic concentration-awake.Anesth Analg. 2001;93(4):947–953

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2010-1142 originally published online May 23, 2011;

2011;127;e1464

Pediatrics

Catherine Billoët, Violaine Dequenne and Peter Onody

Francisco Reinoso-Barbero, Samuel I. Pascual-Pascual, Raul de Lucas, Santos García,

Children: A Randomized Trial

Equimolar Nitrous Oxide/Oxygen Versus Placebo for Procedural Pain in

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/127/6/e1464

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/127/6/e1464#BIBL

This article cites 23 articles, 7 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

edicine_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/anesthesiology:pain_m

Anesthesiology/Pain Medicine

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/toxicology_sub

Toxicology

sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/emergency_medicine_

Emergency Medicine following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2010-1142 originally published online May 23, 2011;

2011;127;e1464

Pediatrics

Catherine Billoët, Violaine Dequenne and Peter Onody

Francisco Reinoso-Barbero, Samuel I. Pascual-Pascual, Raul de Lucas, Santos García,

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/127/6/e1464

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.