neurologic deficits. Indeed, in all 6 infant cases re-viewed by Enberg and Kaplan11and 11 out of 12 cases

reviewed by Walter et al,1the diagnosis of SEA was

delayed until evidence of spinal cord impairment was apparent. Most of these infants had permanent neuro-logic injury and poor outcomes.

SEA in children occurs primarily by hematoge-nous spread of the causative organism from distant sites.1,10,11Many authors point to the spinal epidural

network of veins, Batson’s plexus, as a route of in-fection.10 –12This plexus consists of many veins in the

epidural space that anastomose at each spinal seg-ment with the veins of the thoracic and abdominal cavities.13 It is thought that venous blood flowing

from the lower half of the body to the inferior vena cava may be shunted preferentially to this low pres-sure venous system when the intraabdominal or in-trapelvic pressure is elevated,10 –12thereby

predispos-ing the epidural space to seed durpredispos-ing bacteremia. Local trauma appears to be a predisposing factor to SEA in older children.1,10,11In the cases reviewed by

Enberg and Kaplan, 11 out of 46 patients (24%) had a history of blunt trauma to the back. It is postulated that presumably the formation of an epidural hema-toma then acts as a nidus for infection.1,10,11However,

in the infant cases reviewed by Walter,1only 1 out of

12 infants had a history of trauma to the spine.14

Adjacent vertebral osteomyelitis has been reported in 8% to 25% of children with SEA.1,12

Several authors implicate iatrogenic penetrating trauma such as a epidural anesthesia and LP as a risk factor for SEA.10,11,15However, a review of the

litera-ture suggests that the risk of SEA associated with these procedures is extremely small. The largest re-view to date of infectious complications associated with epidural anesthesia in 1620 pediatric patients found only 1 SEA associated with a long-term tun-neled thoracic epidural catheter in an immunocom-promised patient with metastatic osteosarcoma.5

S aureus is the most frequently isolated etiologic agent in pediatric SEA, and was recovered in 54% of the cases reviewed by Enberg and Kaplan11and 75% of

the infant cases reviewed by Walter et al.1Other

organ-isms reported in pediatric SEA include Pneumococcus, otherStreptococcusspecies,Candidaand coliforms.

MRI is the diagnostic tool of choice for SEA. High resolution ultrasound is a useful, noninvasive alter-native that can be done at the bedside of the severely ill infant who may be too unstable to undergo imag-ing in an MRI scanner.3Laminectomy with surgical

decompression and irrigation of the abscess cavity, plus systemic antibiotics for 4 to 8 weeks after drain-age is the traditional treatment for SEA. The duration of systemic antibiotics may need to be extended in cases of SEA with adjacent osteomyelitis.1Some

au-thors support a limited laminectomy3,10,16 to

mini-mize the subsequent risk of kyphosis. Walter et al1

reported the lone case where treatment via percuta-neous drainage was successful. Although this ap-proach offers the advantage of avoiding a laminec-tomy that can potentially lead to permanent spinal deformity in young infants and children, the authors concede that this should only be attempted if there is

no adjacent bony or disk involvement, or as an alter-native in a poor surgical candidate.

CONCLUSION

In summary, SEA in preverbal children is a rare but potentially devastating disease entity that often has a nonspecific presentation, requiring a high in-dex of suspicion for timely diagnosis and treatment. It should be considered in any young child with fever and spinal stiffness or tenderness, with or with-out neurologic deficits. It should also be considered when LP yields frank pus, when the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture yieldsS aureus, or when the CSF findings are consistent with a parameningeal focus with sterile cultures. CSF findings that suggest a parameningeal focus include CSF pleocytosis, nega-tive Gram’s stain and culture, normal glucose, and elevated protein.17 Prompt surgical treatment and

antibiotics should be undertaken to minimize the risk of progressive and permanent neurologic im-pairment. Our case illustrates that extensive spinal involvement may result in excellent outcomes and is the first to describe Currarino triad with SEA.

Kenneth A. Liu, MD* Jan D. Luhmann, MD*‡

*Department of Pediatrics ‡Division of Emergency Medicine

Washington University School of Medicine St Louis Children’s Hospital

St Louis, MO 63110-1077

REFERENCES

1. Walter RS, King JC Jr, Manley J, Rigamonti D. Spinal epidural abscess in infancy: successful percutaneous drainage in a nine-month-old and review of the literature.Pediatr Infect Dis J.1991;10:890 – 894

2. Marks WA, Bodensteiner JB. Anterior cervical epidural abscess with pneumococcus in an infant.J Child Neurol.1988;3:25–29

3. Gudinchet F, Chapuis L, Berger D. Diagnosis of anterior cervical spinal epidural abscess by US and MRI in a newborn.Pediatr Radiol.1991;21: 515–517

4. Firsching R, Frowein RA, Nittner K. Acute spinal epidural empyema: observations from seven cases.Acta Neurochir (Wien).

5. Strafford MA, Wilder RT, Berde CB. The risk of infection from epidural analgesia in children: a review of 1620 cases.Anesth Analg. 1995;80: 234 –238

6. Currarino G, Coln D, Votteler T. Triad of anorectal, sacral and presacral anomalies.AJR Am J Roentgenol.1981;137:395–398

7. Kochling J, Pistor G, Marzhauser Brands S, Nasir R, Lanksch WR. The Currarino syndrome— hereditary transmitted syndrome of anorectal, sacral and presacral anomalies. Case report and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1996;6:114 –119

8. Lee SC, Chun YS, Jung SE, Park KW, Kim WK. Currarino triad: ano-rectal malformation, sacral bony abnormality, and presacral mass. A review of 11 cases. J Pediatr Surg.1997;32:58 – 61

9. Janneck C, Holthusen W. The Currarino triad—a study of 4 cases.Z Kinderchir. 1988;43:112–116

10. Fischer EG, Greene CS Jr, Winston KR. Spinal epidural abscess in children.Neurosurgery.1981;9:257–260

11. Enberg RN, Kaplan RJ. Spinal epidural abscess in children: early diag-nosis and immediate surgical drainage is essential to forestall paralysis. Clin Pediatr.1974;13:247–253

12. Rockney R, Ryan R, Knuckey N. Spinal epidural abscess: an infectious emergency. Clin Pediatr.1989;28:332–334

13. Batson OV. The function of the vertebral veins and their role in the spread of metastases.Clin Orthrop.1995;312:4 –9

14. Miller WH, Hesch JA. Nontuberculous spinal epidural abscess.Am J Dis Child.1962;104:269 –275

16. de Villiers JC, Cluver PF. Spinal epidural abscess in children.S Afr J Surg.1978;16:149 –155

17. Feigin RD, Cherry JD.Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases.4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 1998

Sweet’s Syndrome as an Initial

Manifestation of Pediatric Human

Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

ABSTRACT. We report a 3-month-old infant in whom Sweet’s syndrome was a presenting manifestation of pe-diatric human immunodeficiency virus infection. Al-though rare in children, Sweet’s syndrome may be asso-ciated with certain infections and malignancies. The diagnosis of Sweet’s syndrome in a child should always prompt a thorough evaluation to assess for an associated systemic disease. Pediatrics 1999;104:1142–1144; Sweet’s syndrome, neutrophilic dermatoses, human immunodefi-ciency virus infection.

ABBREVIATIONS. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

I

n 1964 Sweet1described a series of 8 middle-agedwomen with fever, leukocytosis, erythematous plaques on the face and extremities, and a dermal infiltrate of neutrophils. He termed this disease “acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis.” It later became known as Sweet’s syndrome2and has been reported in

associ-ation with hematoproliferative disorders, malignan-cies, autoimmune diseases, drug-induced sensitivity reactions, and infections.3In 1992 Hilliquin et al4first

reported Sweet’s syndrome occurring in association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in a young adult woman. We report a 3-month-old infant in whom Sweet’s syndrome was a presenting manifestation of HIV infection.

CASE REPORT

A previously healthy 3-month-old African American male pre-sented to the emergency department with an acute onset of fever and irritability. His intake of formula was decreased but no vom-iting or diarrhea was reported. Physical examination revealed an ill-appearing infant whose temperature was 39.3°C, pulse 180 beats/minute, respiratory rate 60 breaths/minute and blood pres-sure 87/45 mm Hg. Lung sounds were clear. A grade 1/6 systolic murmur was heard along the left sternal border. His abdomen was soft, with normal bowel sounds. There was no skin rash. His hemoglobin was 8.8 mg/dL and platelet count was 650 000/mm3.

The white blood cell count was 11 000/mm3, with 34% segmented

neutrophils, 15% band forms, 30% lymphocytes, 8% monocytes, and 12% atypical lymphocytes. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) had 8 white blood cells/mm3(3% segmented neutrophils, 30%

lympho-cytes, 57% monocytes), 300 erythrocytes/mm3, glucose 52 mg/dL,

and protein 27 mg/dL. Gram stain of CSF was negative. A chest radiograph revealed increased perihilar markings. Bacterial cul-tures were obtained from blood, urine, stool, and CSF. He was

admitted; intravenous ampicillin and ceftriaxone were started for presumed sepsis.

His general appearance improved and his tachypnea resolved. However, his fevers persisted and his oral intake remained poor. Supplemental nasogastric feedings were initiated. Stool was pos-itive for rotavirus antigen using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ImmunoCard Rotavirus, Meridian Diag-nostics Inc, Cincinnati, OH). On the fourth hospital day ampicillin and ceftriaxone were discontinued after reports of negative bac-terial cultures from the blood, urine, stool, and CSF. Although rotavirus infection could have accounted for his fever and poor feeding, it was not felt to be related to his anemia. The peripheral blood smear revealed teardrop cells, target cells, nucleated red blood cells, immature white blood cell precursors, and hypochro-masia. No blasts were detected. His corrected reticulocyte count was approximately 1.5%. Digital rectal examination revealed formed stool with scant red mucus, hemoccult-positive.

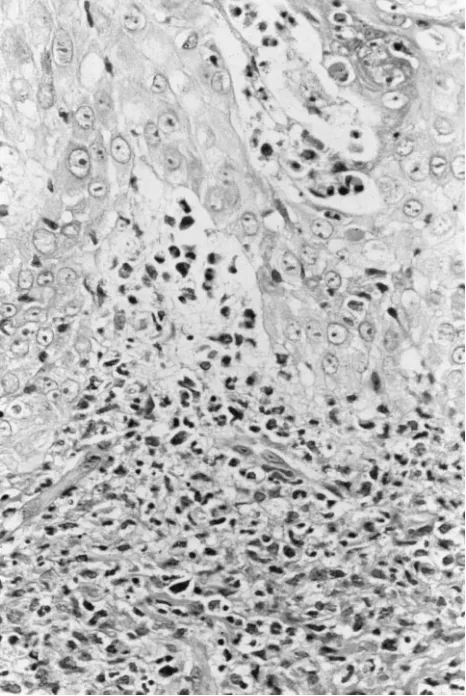

On the sixth hospital day, he developed an unusual papular eruption. Multiple 2- to 15-mm firm, erythematous, round to irreg-ularly shaped papules and plaques with central umbilication and hypopigmentation were noted on the right ear lobe, nose, cheeks, lower lips, and the dorsum of the hands (Fig 1) and feet. Macerated white papules were also present over the dorsum of the tongue and the hard and soft palate. Gram stains of scrapings from a papule and the oral lesions revealed no organisms. Direct fluorescent antibody tests (Bartels Herpes Simplex Virus and Varicella Zoster Virus Biva-lent Reagents, Bartels, Issaquah, WA) for herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus were both negative. A 3-mm punch biopsy (Fig 2) of a hand lesion demonstrated a dense predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate with edema in the upper dermis consistent with Sweet’s syndrome. The deeper reticular dermis and subcutaneous tissue were not involved. In view of the clinical and histologic features, a diagnosis of Sweet’s syndrome was made.

Systemic corticosteroids3and dapsone5have been used for the

treatment of Sweet’s syndrome in adults. We elected to observe

Received for publication Feb 23, 1999; accepted Apr 30, 1999.

Reprint requests to (B.L.C.) Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Division of Infectious Diseases, 3333 Burnet Ave, CH-1 Room 1333, Cincinnati, OH 45229-3039. E-mail: connb0@chmcc.org

PEDIATRICS (ISSN 0031 4005). Copyright © 1999 by the American Acad-emy of Pediatrics.

Fig 1. Multiple round erythematous papules and plaques with central crusted erosions and hypopigmentation on the dorsum of the hand.

the infant because of concern that these medications might exac-erbate his gastrointestinal bleeding. Instead, symptomatic therapy was provided with Polysporin ointment (Warner Wellcome, Mor-ris Plains, NJ) applied every 6 hours to the skin lesions and viscous lidocaine applied orally.

Because infections, malignancies, and hematoproliferative dis-orders are commonly associated with Sweet’s syndrome,3 our

infant underwent further diagnostic evaluations. Repeat blood, urine, stool, and CSF cultures for bacteria and viruses were sterile. All skin and oral lesion viral cultures also remained negative. The Westergren erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 64 mm/hour; se-rum rapid plasma reagin test was nonreactive; and serologies excluded Epstein-Barr virus infection. A repeat chest radiograph was unremarkable and a skeletal series revealed no bone findings suggestive of malignancy. Cranial and abdominal ultrasounds were normal. A bone marrow biopsy on day 16 revealed 100% cellularity with a myeloid predominance and a marked left shift. The megakaryocytes were increased and the number of erythro-cyte precursors was depressed. There was occasional erythroph-agocytosis that was not felt to be significant. Chromosomal anal-yses of his bone marrow aspirate were normal. Overall his bone marrow findings seemed most consistent with a myeloid reaction. Immunologic investigations revealed his serum immunoglob-ulin concentrations to be as follows: immunoglobimmunoglob-ulin A 154 mg/dL (normal range for age: 5– 46 mg/dL), immunoglobulin G 1 370 mg/dL (normal range for age: 176 –581 mg/dL), and immu-noglobulin M 269 mg/dL (normal range for age: 24 – 89 mg/dL). His CD4 lymphocyte count was 368 cells/mm3and his CD4

per-centage was 24%. With his low CD4 lymphocyte count, hyper-gammaglobulinemia, anemia, and Sweet’s syndrome, HIV infec-tion was considered. Initial and follow-up quesinfec-tioning of his

mother failed to disclose any history of behaviors associated with an increased risk of HIV infection. However, a Western blot test revealed antibodies to HIV and an HIV culture was also positive. Both parents, who were asymptomatic, were also found to be HIV-positive.

By day 16, the tongue lesions had resolved into shallow depressions without maceration, and the extremity papules had markedly flattened and become hypopigmented. With the res-olution of his mouth lesions, his oral intake improved and his nasogastric feedings were discontinued. His stools became hemoc-cult-negative. On day 19 the infant’s fever finally abated. By day 23, all his skin lesions had completely reepithelialized with only minimal scarring. No recurrences of his Sweet’s syndrome were noted al-though he died at age 6 months of polymicrobial bacterial pneumo-nia.

DISCUSSION

In 1976 Klock and Oken6presented the first report

of a child with Sweet’s syndrome. To date,,40 pe-diatric cases of Sweet’s syndrome have been report-ed.7 Although rare in children, Sweet’s syndrome

should be considered in any child with multiple, painful, red or violaceous nodules or plaques.

This infant’s clinical and histopatholgic features were typical of Sweet’s syndrome. In 1986 Su and Lui8 proposed 2 major and 4 minor criteria for the

diagnosis of Sweet’s syndrome. Definite diagnosis requires both major criteria and at least 2 of the minor criteria. The major criteria are: 1) abrupt onset of tender, painful erythematous or violaceous plaques or nodules; and 2) predominantly neutro-philic infiltration in the dermis without leukocyto-clastic vasculitis. Minor criteria include: 1) prodro-mal symptoms of fever or infection; 2) concurrent association with fever, arthralgia, conjunctivitis, or underlying malignancy; 3) leukocytosis; and 4) a good response to systemic steroids. In 1989 von den Driesch et al9proposed that an elevated erythrocyte

sedimentation rate should be added as a minor cri-terion. Other clinical manifestations of Sweet’s drome are more variable. Ten cases of Sweet’s syn-drome have been reported in infants ,1 year of age.10 –18 All these infants presented with rash and

fever and were hospitalized for possible sepsis. Seven infants, including this infant, had anemia. This infant’s anemia was probably multifactorial—related to his gastrointestinal bleeding, HIV infection, and Sweet’s syndrome. Two infants had pulmonary in-filtrates by chest radiographs. These inin-filtrates did not respond to antibiotics but did improve as the Sweet’s syndrome resolved, suggesting the possibil-ity of pulmonary neutrophilic infiltrates.14Although

oral lesions have been reported in adults with Sweet’s syndrome,9 they are an infrequent sign.

Whether this infant’s oral lesions were attributable to Sweet’s syndrome or another etiology could not be precisely determined.

The clinical manifestations of Sweet’s syndrome are nonspecific and hence, infections and other skin conditions must be considered. The differential diag-nosis includes cellulitis, secondary syphilis, drug re-action, pyoderma gangrenosum, vasculitis, erythema multiforme, erythema nodosum, Behcet’s disease, chronic neutrophilic plaques, and bowel-bypass syn-drome.3,19 Occasionally, severe dermal edema in

Sweet’s syndrome may result in vesicles and pus-tules,20mimicking herpes simplex and varicella

zos-ter virus infection. Early skin biopsy for

logic examination, special stains, and cultures is essential to establish the diagnosis and guide addi-tional diagnostic evaluations and therapy decisions. Although Sweet’s syndrome may be idiopathic, often the patient, as illustrated by this infant, has an associated systemic disease.3Approximately 15% of

adults have an associated malignancy, with hemato-logic malignancies being the most common.21 In

in-fants and children, associated conditions include oti-tis media, sterile osteomyelioti-tis, aseptic meningioti-tis, and leukemia.15Infrequently, Sweet’s syndrome has

been attributed to medications including antibiot-ics.22 This infant’s antibiotics were discontinued

be-fore his skin lesions appeared, and his fever persisted for 15 days after the antibiotics were stopped, mak-ing drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome less likely. Be-cause immunodeficient individuals may chronically shed rotavirus,23 the finding of rotavirus antigen in

this infant’s stool does not necessarily imply that his rotavirus infection was acute. Given the previously described association between Sweet’s syndrome and HIV infection in adults,4the finding of Sweet’s

syndrome in this infant prompted testing that led to his diagnosis of HIV infection.

The etiology of Sweet’s syndrome remains un-known but its association with parainflammatory and paraneoplastic conditions suggests that it may be the result of a hypersensitivity reaction to a bac-terial, viral, or tumor antigen.24Release of cytokines

from activated T-lymphocytes may contribute to the local and systemic activation of neutrophils.25

How-ever, the relationship between T-lymphocyte activa-tion in Sweet’s syndrome and associated diseases such as HIV needs to be clarified. These concepts of pathogenesis are also supported by the rapid re-sponse seen when systemic corticosteroids, the ther-apy of choice for Sweet’s syndrome, are adminis-tered.3 Interestingly, this infant’s Sweet’s syndrome

resolved without specific therapy and no recurrences were noted. Spontaneous resolution of Sweet’s syn-drome and a lack of recurrences despite progression of the underlying associated disease have been pre-viously reported by Saxe and Gordon.10

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of a child in whom Sweet’s syndrome was an initial manifestation of HIV infection. A history of HIV-related risk factors may not always be obtained from parents, especially when, as in this case, they were infected through heterosexual contact and were un-aware of the serostatus or risk behaviors of their previous heterosexual partners.26 We recommend

HIV testing for children with Sweet’s syndrome of otherwise unexplained etiology.

Rebecca C. Brady, MD* Joan Morris, MD‡

Beverly L. Connelly, MD*

*Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases

‡Division of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Cincinnati, OH 45229-3039

Susan Boiko, MD

Division of Pediatric Dermatology

University of California San Diego School of Medicine

San Diego, CA 92123

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr Yvette Casey-Hunter for her assistance in our patient’s care.

REFERENCES

1. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349 –356

2. Whittle CH, Beck GA, Champion RH. Recurrent neutrophilic dermato-sis of the face: a variant of Sweet’s syndrome.Br J Dermatol. 1968;80: 806 – 810

3. von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic der-matosis).J Am Acad Dermatol.1994;31:535–556

4. Hilliquin P, Marre JP, Cormier C, Renoux M, Menkes CJ. Sweet’s syndrome and monoarthritis in a human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient.Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:484 – 486

5. Aram H. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome). Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:245–247

6. Klock JC, Oken RL. Febrile neutrophilic dermatosis in acute myeloge-nous leukemia.Cancer.1976;37:922–927

7. Gray LC, Abele DC. Annular erythematous plaques and tibial pain in a child. Sweet syndrome.Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:625– 626

8. Su WPD, Liu H-NH. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome.Cutis. 1986;37:167–174

9. von den Driesch P, Schlegel Gomez R, Kiesewetter F, Hornstein OP. Sweet’s syndrome: clinical spectrum and associated conditions.Cutis. 1989;44:193–200

10. Saxe N, Gordon W. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome).S Afr Med J. 1978;53:253–256

11. Itami S, Nishioka K. Sweet’s syndrome in infancy.Br J Dermatol.1980; 103:449 – 451

12. Hazen PG, Kark EC, Davis BR, Carney JF, Kurczynski E. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis in children.Arch Dermatol.1983;119:998 –1002 13. Kibbi AG, Zaynoun ST, Kurban AK, Najjar SS. Acute febrile

neutro-philic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome): case report and review of the literature.Paediatr Dermatol. 1985;3:40 – 44

14. Collins P, Rogers S, Keenan P, McCabe M. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis in childhood.Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:203–206

15. Dunn TR, Saperstein HW, Biederman A, Kaplan RP. Sweet syndrome in a neonate with aseptic meningitis.Pediatr Dermatol.1992;9:288 –292 16. Eghrari-Sabet JS, Hartley AH. Sweet’s syndrome: an immunologically

mediated skin disease?Ann Allergy.1994;72:125–128

17. Sedel D, Huguet P, Lebbe C, Donadieu J, Odievre M, Labrune PH. Sweet syndrome as the presenting manifestation of chronic granuloma-tous disease in an infant.Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:237–240

18. Hassouna L, Nabulsi-Khalil M, Mroueh SM, Zaynoun ST, Kibbi A-G. Multiple erythematous tender papules and nodules in an 11-month-old boy.Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1507–1510

19. Storer JS, Nesbitt LT Jr, Galen WK, DeLeo VA. Sweet’s syndrome.Int J Dermatol. 1983;22:8 –12

20. Fitzgerald RL, McBurney EI, Nesbitt LT Jr. Sweet’s syndrome.Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:9 –15

21. Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome and malignancy.Am J Med. 1987;82:1220 –1226

22. Walker DC, Cohen PR. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: case report and review of drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome.J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:918 –923 23. Saulsbury F, Winkelstein J, Yolken R. Chronic rotavirus infection in

immunodeficiency.J Pediatr. 1980;97:61– 65

24. Lear JT, Atherton MT, Byrne JPH. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet’s syndrome.Postgrad Med J. 1997;73:65– 68 25. Alvaro T, Garcia del Moral R, Gomez-Morales M, Aneiros J, O’Valle F.

Immunopathological studies of Sweet’s syndrome.Br J Dermatol. 1991; 124:111–112

26. Ellerbrock TV, Lieb S, Harrington PE, et al. Heterosexually transmitted human immunodeficiency virus infection among pregnant women in a rural Florida community.N Engl J Med.1992;327:1704 –1709

DOI: 10.1542/peds.104.5.1142

1999;104;1142

Pediatrics

Rebecca C. Brady, Joan Morris, Beverly L. Connelly and Susan Boiko

Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

Sweet's Syndrome as an Initial Manifestation of Pediatric Human

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/104/5/1142

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/104/5/1142#BIBL

This article cites 26 articles, 1 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/hiv:aids_sub

HIV/AIDS

b

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/infectious_diseases_su

Infectious Disease

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.104.5.1142

1999;104;1142

Pediatrics

Rebecca C. Brady, Joan Morris, Beverly L. Connelly and Susan Boiko

Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

Sweet's Syndrome as an Initial Manifestation of Pediatric Human

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/104/5/1142

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.

the American Academy of Pediatrics, 345 Park Avenue, Itasca, Illinois, 60143. Copyright © 1999 has been published continuously since 1948. Pediatrics is owned, published, and trademarked by Pediatrics is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly publication, it

at Viet Nam:AAP Sponsored on August 30, 2020

www.aappublications.org/news