BY

MWANDO ROBERT NGILE (B. Ed Arts)

N50/CE/14479/09

A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE

REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE (ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION) IN THE SCHOOL OF

ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES OF KENYATTA UNIVERSITY

DECLARATION

This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other university or any other academic award.

Signature: __________________________ Date: ________________________ Mwando Robert Ngile.

Department of Environmental Education

SUPERVISORS

We confirm that the work reported in this thesis was carried out by the candidate under our supervision and has been submitted with our approval as university supervisors.

Signature: _______________________________ Date: _____________________ Dr. Samuel C.J Otor

Department of Environmental Sciences

Signature: _______________________________ Date: __________________ Dr. Cecilia Gichuki

DEDICATION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The successful completion of this thesis would not have been achieved without the backing of various individuals whose efforts I would like to acknowledge. First and foremost, I thank the Almighty God for granting me the good physical and mental health that enabled me to conceptualize, design, execute and present this thesis.

I owe an immense debt of gratitude to my two dedicated supervisors, Dr. Samuel C.J Otor and Dr. Cecilia Gichuki for the encouragement, inspiration, guidance and advice they gave me throughout the research period and preparation of this thesis report. I am particularly indebted to the two for their careful reading of the draft thesis report, insightful criticism and patient encouragement which aided the writing of this thesis in innumerable ways. I am equally grateful to the ATCM-CD of WRMA Athi Catchment Area, Ms. Millicent Kariithi. I also recognise the Middle Athi Catchment Management Officers, Mr. Kiamba and Ms. Jaqueline Mboroki. Special mention goes to the technical manager of Machakos Water and Sewerage Company Mr. Isaac Musya anSd the Deputy Sub-County Water Officer, Mr. George Mutungi. I am grateful to the aforementioned officers for their cooperation and professional assistance that led to the success in data collection during the field study.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Declaration……….i

Dedication……….ii

Acknowledgement………iii

Table of contents………..iv

List of tables……….vi

List of figures……….viii

List of plates……….ix

Acronyms and Abbreviations………x

Abstract………...xi

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION………...1

1.1. Background to the study………...1

1.2. Statement of the problem………..3

1.3. Research questions………...5

1.4. Objectives of the Study……….5

1.5. Research Hypotheses………6

1.6. Justification of the Study………..6

1.7. Significance of the Study………..6

1.8. Scope and limitations of the Study………...7

1.9. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework………...7

1.10. Operational definitions of terms………...9

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW………..10

2.1. Introduction………..10

2.2. Water resources management………...10

2.3. Stakeholder participation in water resources management………..12

2.4. Participatory approach in Kenya‟s water sector reforms………..15

2.5. Challenges to stakeholder participation in water resources management……19

2.6. Stategies of addressing challenges to stakeholder participation………...23

CHAPTER THREE: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY……….. …………...27

3.1. Study Area………27

3.2. Climate………..28

3.3. Hydrology……….29

3.4. Research Design………...29

3.5. Population……….30

3.6. Sample and Sampling procedure………..30

3.7. Data collection procedures………...32

3.8. Research instruments………33

3.9. Administration of research instruments………34

3.10. Data analysis………...35

3.11. Research constraints………...35

CHAPTER FOUR: RESULTS AND DISCUSSION………..36

4.2. Management of water resources at household level……….36

4.3. Water Resources Management by Community Groups ………..51

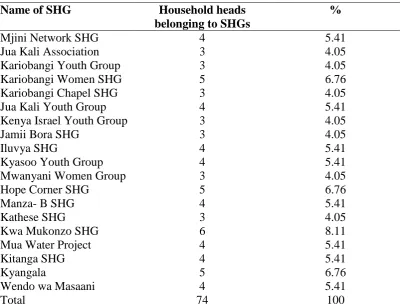

4.3.1. Community Water Self Help Groups (SHGs)………...51

4.3.2. Water Resource Users‟ Associations (WRUAs)………...62

4.4. Planners and Policy Makers (institutions)………72

4.4.1. Sub-County Water Office (SCWO)………...72

4.4.2. Water Resources Management Authority (WRMA)……….76

4.4.3. Catchment Area Advisory Committee (CAAC)………86

4.4.4. National Environment Management Authority (NEMA)………..88

4.4.5. Tana and Athi Rivers Development Authority (TARDA)………93

4.5. Water Service Providers………...95

CHAPTER FIVE: SUMMARY, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS………...103

5.1. Summary of findings………..103

5.2. Conclusions………105

5.3. Recommendations………...106

5.4. Recommendations for further Research……….107

References……….108

Appendices………112

LIST OF TABLES

TABLE PAGE

Table2.1- Roles and mandates of institutions 17

Table 3.1- Sampled sub-locations and households 31

Table 4.1- Characteristics of households 37

Table 4.2- Variation in water availability 40

Table 4.3- Mean water quantities accessed 43

Table 4.4- Test for mean and deviation for water 44

Table 4.5- Reasons for non-membership 45

Table 4.6- Participation in water projects 46

Table 4.7- Education, training and impact of respondents 47

Table 4.8- Challenges faced by households 48

Table 4.9- Strategies of addressing challenges 49

Table 4.10- Households‟ collaboration with institutions 50

Table 4.11 Respondents‟ rating of water authorities 51

Table 4.12- Membership to water SHGs 52

Table 4.13-Types of water supply 54

Table 4.14- Projects initiated 55

Table 4.15- Activities undertaken by SHGs 57

Table 4.16- Factors SHGs considered 57

Table 4.17- Successful projects by SHGs 58

Table 4.18- Community water points operated by SHGs 59

Table 4.19- Test for mean and deviation for water 60

Table 4.20- Challenges faced by water SHGs 62

Table 4.21- WRUAs in Machakos Sub-County 63

Table 4.22 –Rating of causes of acute water scarcity 64

Table 4.23- Activities accomplished by WRUAs in Machakos 65

Table 4.24- WDC activities by WRUAs in Machakos 66

Table 4.25- WDC Funding Ceilings 67

Table 4.26- Per capita water withdrawal from sources 68

Table 4.27- Test for mean and deviation for water 68

Table 4.29- Challenges facing WRUAs 71

Table 4.30- Activities carried out by SCWO in Machakos 73

Table 4.31- Water sources constructed by SCWO 74

Table 4.32- Test for mean and deviation for water from SCWO 74

Table 4.33- Challenges facing SCWO 76

Table 4.34- WRUA status in WDC in Machakos 78

Table 4.35- WSTF funded activities by WRUAs 80

Table 4.36- Proposed WRUAs in Machakos Sub-County 81

Table 4.37- WRMA-WRUA collaboration 82

Table 4.38- Test for mean and deviation for water sources 83

Table 4.39- Challenges facing WRMA and solutions 85

Table 4.40- CAAC partnership with others 87

Table 4.41- Challenges faced by CAAC 87

Table 4.42- Catchment conservation activities by NEMA 89

Table 4.43- Water resources initiated by NEMA 90

Table 4.44- Test for mean and deviation for NEMA water resources 91

Table 4.45- RRMAs in Machakos 91

Table 4.46- Reasons for non-membership to RRMAs 92

Table 4.47- Water resource management by TARDA 94

Table 4.48- Projects undertaken by MWSCO 97

Table 4.49- Test for mean and deviation for MWSCO water sources 98

LIST OF FIGURES

FIGURE PAGE

Figure 1.1- Conceptual framework 8

Figure 2.1- Separation of functions 16

Figure 3.1- Map of Machakos County 28

Figure 4.1- Reliability of water for specific uses 39

Figure 4.2- Households noting water sources seasonally dried up 40

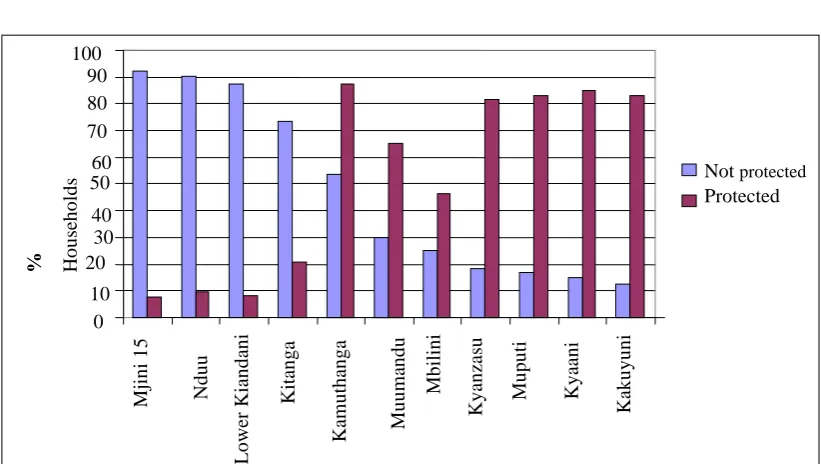

Figure 4.3- Households using protected or non-protected water 42

Figure 4.4- Actions taken by households 43

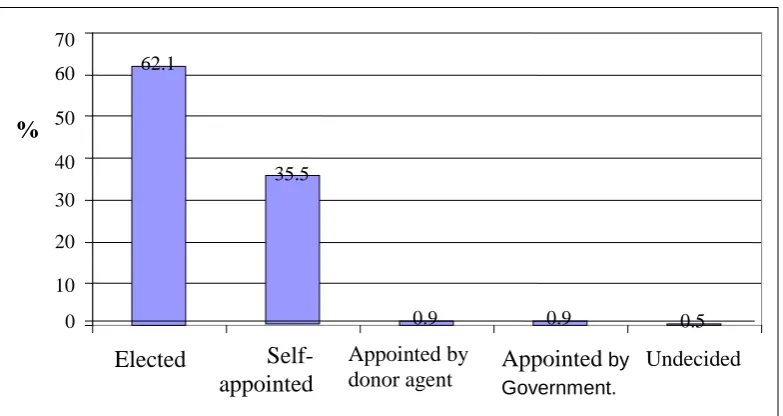

Figure 4.5- Formation of committees 53

Figure 4.6 Water resources managed by SHGs 53

Figure 4.7 Water discharge in three rivers 84

LIST OF PLATES

PLATE PAGE

Plate 4.1- Inyooni Shallow well 38

Plate 4.2- A dry section of River 41

Plate 4.3- Manza “B” Water Project 55

Plate 4.4- Water kiosk at Kenya Israel 61

Plate 4.5- Kyandili sand dam 69

Plate 4.6- SCWO personnel drilling a borehole 75

Plate 4.7- Kitulu Rock Catchment 77

Plate 4.8- Illegal sand harvesting 93

Plate 4.9- Tree nursery established by TARDA 95

Plate 4.10- Maruba Dam 98

Plate 4.11- MWSCO Water kiosk at Mjini 15 99

Plate 4.12- Private water bowser supplying water 101

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ASAL- Arid and Semi Arid Land

CDF- Constituency Development Fund

CDTF- Constituency Development Trust Fund

EMCA-Environmental Management and Co-ordination Act FAO-Food and Agriculture Organization

IAHS- International Association of Hydrological Sciences ICWE- International Conference on Water and Environment

Inades-Formation- African Institute for Social and Economic Development IPCC- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

IUCN- International Union for Conservation of Nature IWMI- International Water Management Institute IWRM- Integrated Water Resources Management MDG- Millennium Development Goal

MWI- Ministry of Water and Irrigation

NWRMS- National Water Resources Management Strategy PPIAF- Public Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility

REMPAI- Resource Management and Policy Analysis Institute SCMP- Sub-Catchment Management Plan TANATHI-Tana and Athi Rivers‟ Water Services Board TARDA- Tana and Athi Rivers Development Authority

UNCED- United Nations Conference on Environment and Development UNDP-IHE- United Nations Development Programme-Institute of Hydraulic Engineering

UNDP- United Nations Development Programme UNEP- United Nations Environment Programme

UNESCO- United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization UNICEF- United Nations Children‟s Fund

WAC-World Agro-forestry Centre

WCED-World Commission on Environment and Development WHO- World Heath Organisation

WRMA- Water Resource Management Authority

ABSTRACT

Stakeholder participation has been shown to be an effective approach in increasing access to safe water and sanitation in many parts of the world. This study investigated stakeholder participation in management of water resources in Machakos Sub-County of Machakos County, Kenya. Specifically, it sought to assess the level of community participation in water resources management, collaboration between stakeholders, stakeholder contribution in increasing access to reliable water resources and the challenges facing the participatory approach of water resources management in the Sub-County. The research design used was a descriptive survey. The sampling techniques entailed simple random sampling and purposive sampling. The research tools comprised household questionnaires, interview schedules, observation record sheets and photography. A total of 217 households were selected through simple random sampling technique. The data were analyzed statistically and findings presented using both descriptive and inferential statistics. The study revealed that the key stakeholders in water resources management in the Sub- County were; WRMA, NEMA, CAAC, Tana-Athi WSB, SHGs, MWSCO, WRUAs, TARDA and private water service providers. The results of the study showed that the mean quantity of water available for domestic use from household constructed sources was significantly lower than the recommended BWR of 50 litres/ person/ day (x=29.61 litres/ person/ day, σ=19.41, p 0.05, n= 217, df=2). Further, most of the household heads participated in community water resources management activities despite not belonging to community- based water associations(x2= 4.564, p= 0.205, n= 217,df= 3). The study also found that there was a significant relationship between training in water resources management and the impact one made in water resources management activities (r= 0.427, p= 0.001, n= 217, df= 1). Those who were trained made a greater impact. The study also established that there was a significant association between the level of awareness among household heads and their collaboration with water resource management institutions in the Sub-County (x2= 46.270, p= 0.001, n= 217, df= 2). Community participation through SHGs and WRUAs has a big potential in increasing access to reliable water resources in the Sub-County. The water supply projects initiated by the identified SHGs resulted to a high daily per capita water availability (x= 37.85 litres, σ=8.807, p≤ 0.05, df=20). Although most of the WRUAs were in the formative stages, one (Itetani) had implemented water supply projects that raised the daily per capita water availability for people in its sub-catchment area (x=37.09, p˂ 0.05, σ=4.13, df=10, n=11). Other stakeholder institutions which worked with communities and led to an increase in water availability were SCWO, MWSCO and WRMA. The main challenge facing the stakeholders was financial constraint. The results of this study show that for participatory water resources management to take root in Machakos Sub-County, various issues need to be addressed such as; strengthening community-based water SHGs financially and technically, WRMA to fast track capacity-building and SCMP development for WRUAs in the Sub-County, mainstreaming the private water service providers, integration of stakeholders with conflicting roles and awareness creation among the key stakeholders.

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background to the Study

In September 2000,189 UN member States adopted the MDGs, setting clear, time-bound targets for making real progress on the most pressing development issues we face. Goal 7 was to ensure environmental sustainability and one of its targets was to halve, by 2015, the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation (UNICEF and WHO, 2004).The human society is facing four large problems defined as water, food, energy and environment. Water related problems are the most essential since they implicitly interact with the other three. Production of food and generation of energy critically depend on water (IWMI, 2007).

It has been estimated that 1.2 billion people become sick annually as a result of poor quality drinking water (Cech, 2010). UNEP (2004) projected that two thirds of the world‟s population will be living in water stressed countries by the year 2015. In some places water is abundant, but getting it to the people is difficult because of restricted access as a result of political and socio-cultural issues. In other places, the shortage is due to poor management of the available water resources (Abu-Eid, 2007).

Arguably, the hottest topic in the water industry today is the question of possible impacts of climate change on the availability of water resources, including their quantification for planning purposes (Kresik, 2009). Climate change will affect all facets of society and the environment, with strong implications for water now and in the future. The climate is changing at an alarming rate, causing temperature rise, shifting patterns of precipitation and more extreme events. According to IPCC (2007), by 2020, between 75 and 250 million people in Africa are projected to be exposed to increased water stress due to climate change.

in adequate quantities. However, it is regarded as water scarce country with a natural endowment of freshwater per capita per annum estimated at about 1985m3 with flood water incorporated and 647m3 without incorporating floodwater (Republic of Kenya, 2012). Only about 57% of the population has access to improved water source. This compares unfavourably with the neighbouring countries of Tanzania and Uganda, with per capita levels of 2696 and 2940m3 respectively (UNDP, 2006). Moreover, Kenya‟s per capita is expected to drop to 250m3 in 2025 when the population is projected to rise to sixty million and 235m3 by 2035, unless effective measures to address the challenges facing water resources management are implemented (Republic of Kenya, 2007d).

As noted by Kariuki (2010), climate change is associated with increased water scarcity and stress in the ASAL regions of the country which comprise more than three quarters of Kenya's total land surface area. In these regions (where Machakos Sub-county is located), water is lost through evaporation and uncontrolled surface run-off. Most of the rivers are seasonal and yield water after the rainy season but remain dry for the rest of the dry period. The main sources are boreholes and a few perennial rivers which have low flows in the dry season.

Scarcity and unreliability of water resources has been impacting negatively on agriculture, domestic water use and livestock development in various parts of Kenya. As a consequence, various regions of the country are faced with serious challenges related to water resources management for continued social and economic development (Agwata & Abwao, 2007). However, this would entail involving all the actors in the water sector in participatory management approaches that pay attention to the interests of the stakeholders and their water-related activities which include agriculture, power generation, domestic, industrial use, and fishing (REMPAI, 2009).

levels to communities, based on their ability and willingness to pay (UNICEF & WHO, 2004). Based on this understanding, the country has experienced a systematic shift toward the decentralization of water management activities since the year 2002. In an effort to address the issues and challenges in the water sector as well as the severity of water crisis, the country embarked on a comprehensive water sector reforms programme which culminated in the enactment of the Water Act, 2002. The water sector reforms took cognizance of MDG 7 (a) which aimed at integrating the principles of sustainable development into the country‟s policies and programmes (Republic of Kenya, 2002). As pointed out by WRMA (Republic of Kenya, 2012), due to the cross-cutting nature of water resources, their management should be approached through IWRM principles which require participation of stakeholders to execute programmes.

It is against this background that this study aimed to assess the impact of stakeholder participation in management of water resources in Machakos Sub-county. It investigated various aspects of water resources management such as water resource use, water resource protection and conservation, resource endowment assessment, resource valuation, government and community institutions relating to water resources, and local technology used in the Sub-county. Environmental elements such as; climate (dry and wet seasons), landscape and water bodies (rivers, boreholes, dams, and springs); and events like droughts, were used during the study. This was done regarding the balancing of the economic, social and ecological components as envisaged in the sustainable development concept (UNCED, 1992), the Water Act 2002, NEMA‟s environmental regulations related to water resources and the IWRM approach.

1.2 Statement of the Problem

management. However, implementation of the roles has not taken root in many parts of the country (Kariuki, 2010). As a result, shortage of water threatens the progress toward sustainable development and the country‟s Vision 2030 goals on water and sanitation. Kenya‟s target for water and sanitation is to increase access to safe water and sanitation in rural and urban areas through raising the standards of the country‟s overall water resources management, storage and harvesting capability (Republic of Kenya, 2007a). This may become a pipe-dream if institutional arrangements are not reformed so that all stakeholders are fully involved with all aspects of policy formulation and implementation.

As pointed out by WRMA (2009), water scarcity in Machakos Sub-County has been accelerated by increasing demand in the domestic and agricultural sectors. This is associated with rapid population growth and unregulated use of water, especially in the rural areas, which has caused over-exploitation and degradation of water resources. Catchment degradation and extraction of riverine resources such as sand, ballast, building stones and vegetation has led to drying of rivers and shallow boreholes in the Sub-county. This is being done in contravention of the extraction guidelines issued by NEMA (2008) which stipulate a participatory approach in rehabilitating rivers involving the District Environment Committees (DEC), TSHC, RRMAs, sand traders and local leaders. Some water resources such as rivers, shallow boreholes and streams, have been polluted by industrial effluent, commercial wastewater, agro-chemicals and domestic waste (TANATHI, 2009).

1.3 Research Questions

The following research questions were used to guide the study:

i) How do the actors in water resources management in Machakos Sub-county involve the community?

ii) Does training in water resources management affect the impact stakeholders make in the roles they play in water resources management in Machakos Sub-county?

iii) In which ways do stakeholders in Machakos Sub-county collaborate to promote sound water resources management?

iv) How has stakeholder participation influenced access to water resources in Machakos Sub-county?

v) How do stakeholders address the challenges they face in management of water resources in Machakos Sub-county?

1.4 Objectives of the Study 1.4.1 General Objective

To assess the role of stakeholder participation in improving the water scarcity situation in Machakos Sub-County through water resources management

1.4.2 Specific Objectives

i). To evaluate the level of community involvement in water resources management activities in Machakos Sub-county.

ii). To find out the effect of training on the impact made by stakeholders in the roles they played in water resources management in Machakos Sub-county. iii). To assess the level of collaboration among stakeholders in water resources

management in Machakos Sub-county.

iv). To evaluate the contribution of stakeholder participation in improving access to reliable water resources in Machakos Sub-county.

v). To examine the challenges facing stakeholder participation in the Sub-county and strategies used to address them.

1.5. Research Hypotheses

In order to ascertain the factors influencing stakeholder participation in water resources management activities in Machakos Sub-county, the following hypotheses were tested:

1. Ho: The level of community involvement in water resources management

activities in Machakos Sub-county is significantly low.

2. Ho: Training of community members in water resources management does

not significantly improve the impact they made in community water projects.

3. Ho: Stakeholder participation has not improved access to reliable water

resources in Machakos Sub-county.

4. Ho: Stakeholder collaboration in water resources management in Machakos

Sub-County is significantly low.

1.6 Justification of the Study

Water resource management problems are being experienced in many regions of the world and especially the developing countries where they are impacting negatively on the socio-economic development of the countries affected. These, if not urgently addressed will ultimately lead to stagnation in the countries and exacerbate poverty levels in those countries. This, therefore, calls for all stakeholders including policy makers, planners and water users, among others, to work together in seeking approaches that will ensure the sustainable management of the dwindling water resources. Machakos Sub-county, which is found in a catchment basin situated in the ASAL areas of Kenya, that is Athi, faces a myriad of water related challenges. This situation clearly calls for a study on how the key actors can collaborate in managing the few water resources sustainably so as to bring about improved access to water.

1.7 Significance of the Study

will play their roles with commitment to ensure that the scarce water resources are managed in a sustainable manner. This is in realization of the crucial functions that water plays in the environmental, economic and social components of life. It is also expected to contribute towards attainment of the MDG 7 target on water by increasing accessibility of water especially in middle size towns and rural areas of Kenya. Moreover, the results of the study are aimed at contributing towards attainment of Kenya‟s Vision 2030 target of increasing access to safe water and sanitation through raising the standards of water resources management, storage and harvesting capability.

1.8 Scope and Limitations of the Study

The study covered Machakos Sub-county and focused on issues related to management of water resources at household, community and institutional levels. It evaluated the roles played by key stakeholders, involvement of community in water resources management activities, stakeholders, contribution in increasing access to reliable water resources and the challenges the stakeholders faced. The study was limited to only one county. For conclusive results, all the sub-counties with similar water problems should be studied.

1.9 Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks

social needs while ensuring protection of ecosystems for future generations. Water has many different and competing uses which demand coordinated action involving stakeholders in an open, flexible process. These stakeholders can be drawn from the public sector, civil society, regional and international programmes; and community-based organizations (Republic of Kenya, 2012). The IWRM principle was deemed to be fit for this study for it focuses on bringing together decision-makers and stakeholders across various sectors that have an impact on water resources so as to set policy and make sound, balanced decisions in response to specific water challenges. The study was based on the conceptual framework shown in Figure 1.1:

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Water scarcity and catchment degradation

Figure1.1.Stakeholder-collaboration in water resources management WATER

RESOURCES: Rivers/ streams Wells

Boreholes House-Roofs Pans

Springs

RESOURCE PROVIDERS: Tana- Athi

WSB MWSC

Private suppliers Absent

Collaboration in water resources management

RESOURCE USERS: Households

Institutions Irrigation farmers Industries

RESOURCE PLANNERS & POLICY MAKERS:

WRMA NEMA TARDA

Sub- County Water Office

Improved access to clean and reliable water resources

Interaction between the water resources and collaboration in water resources management shows the available water resources in Machakos Sub-county that can be accessed by the residents for use in various sectors. These sources need to be carefully managed through a participatory approach involving various actors. Interaction between resource planners and policy makers within the Sub-County and collaboration in water resource management shows the participation of these stakeholders in developing projects that could make the resource source available for the resource users to access for various uses.

Interaction between resource providers and collaboration in water resource management shows the involvement of resource providers who set rules and conditions for the resource users on the mode of accessing the resource, rate and mode of payment for water, and mode of water distribution. Resource providers ensure that the resource is well managed and increase the available resource sources. Interaction between resource users and collaboration in water resources management shows that the available water resources need to be utilized well while ensuring the sources are protected and conserved to promote sustainability. This collaboration among stakeholders will lead to improved access to clean and reliable water resources (Present), thus addressing the problem of water scarcity and catchment degradation (Absent).

1.10 Operational Definitions of Terms

Collaboration: Partnership among stakeholders in management of water resources Community participation: A process through which stakeholders influence and share control over development and management initiatives, decisions and resources that affect them.

Water reliability: Is the availability of water at the source during the time of need. Stakeholder: A person or entity which has influence over or is affected by a

certain activity on a resource.

Water resource management: All organized activities and planning regarding water resources development, conservation, protection and control from water adverse effects.

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Introduction

This major section is intended to review the various literature materials on stakeholder participation in water resources management, challenges to participatory water resources management and strategies of addressing them. Its main focus is on what others have done in similar fields so as to identify the knowledge gaps that need to be addressed in this study as well as strengths that can back up the study findings and in giving recommendations.

2.2 Water Resources Management

As pointed out by Tshmanga (2010) Water resources are sources of water that are useful or potentially useful to humans and the surrounding ecosystems. They include both ground and surface water resources such as rivers, wells, springs, dams and lakes. According to him, the way these resources are used for human and environmental activities such as agriculture, industry, household, recreation and environment; the rules and practices surrounding their protection, conservation, governance and participation, aiming at enhancing their relative value, is referred to as water resource management.

urban water supply management. Water resources management uses hydraulic and other structures, complex water resources systems and measures to influence water demand, use, conservation and protection.

As noted by Djordjevic (1993) the complex intricacy of water resources management depends on both, the water demand and the water supply. Therefore, water resources management is a dynamic process of devising alternative sequences or activities that will optimize the achievement of the objectives related to water resources. As noted by Ioulia et al. (2008), in our days water has become one of the most important raw materials, energy carrier and environmental factors in the society, the limited availability of which may considerably hinder the socio-economic development of many regions. The carefully planned management of water resources is therefore, an indispensable requirement.

As explained by Hirji et al. (2002), there already exists an international consensus on the principle of sound water resources management. This has been demonstrated through international actions that go back to the „Water and Sanitation Decade‟ (1980-90), following the Mar del Plata Conference and the resulting action plan of 1977 which led to the emergence of Inter-Secretariat Group on Water Resources of 1990 under the Administrative Co-ordination Council of the UN. Capacity-building in the water sector became the theme of the UNDP-IHE Conference in Deft in 1991.This was quickly followed by the ICWE in Dublin in 1991.Three basic elements of capacity building were identified: the creation of an enabling environment with appropriate policy framework; institutional development, including community participation; and human resources development and strengthening of managerial systems.

Further, the principles put emphasis on recognition of water as an economic good, promoting cost-effective intervention, supporting participatory efforts to manage water resources and focusing on actions to improve the lives of people and the quality of their environment. They also stressed adopting positive policies to address women‟s needs, empower women and incorporating mechanisms for conflict resolution (Ibid).

The ICWE called for innovative approaches to the assessment, development and management of freshwater resources, and provided policy guidance for the UNCED in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in June 1992 which highlighted the need for water sector reforms throughout the world. The Dublin statement reaffirmed that „ it is vital to recognize first the basic right of all human beings to have access to clean water and sanitation at an affordable price, and went on to assert a number of principles. The first is that water must be managed in a holistic way, taking into account interaction among users and environmental impacts. The second principal is that water should be valued as an economic good and managed as a resource necessary to meet basic human rights. Thirdly, institutional arrangements must be reformed so that stakeholders are fully involved with all aspects of policy formulation and implementation. Water management must be devolved to the lowest appropriate level and the roles for NGOs, the private sector and community groups must be enhanced. Lastly, women must play a central part in the provision, management and care of the resource (Turral, 1998).

2.3. Stakeholder Participation in Water Resources Management

expectations in water resources management, the outcome is likely to be positive. The decisions by governments, developers and other water resource managers require the input of the primary stakeholders, such as the communities who are either affected by or benefit from water resources management activities. Agenda 21 highlights the importance of participation in integrating decision-making; in involving different sectors and stakeholders to build capacity and ownership of solutions; in recognizing the role of indigenous communities and empowering the poor and women in the management of natural resources (Brenda & Cesar, 2001).

Participatory approach is an important aspect of IWRM, which, as explained by Biswas et al. (2005) is a comprehensive, participatory planning and implementation tool for managing and developing water resources in a way that balances social and economic needs, and ensures protection of ecosystems for future generations. As noted by Tshmanga (2010), a paradigm shift has emerged in water resources management forums during the last two decades as a result of which, the social, cultural, economic and political dimensions surrounding water have been found to be pivotal for sustainable management of water resources. More attention is being given to communities and societies as well as acknowledging stakeholder participation in water resources management as essential for sustainable development.

three main benefits that can be derived from community participation in water resources management. First, governments, developers and other water resources managers find it easy to make decisions when they involve the input of the primary stakeholders, such as the communities who are either to be affected by or will be the beneficiaries of water resource management activities. Second, the communities are usually aware of the nature of water resources endowment in their respective areas. This makes them appreciate the difficult choices which have to be made in order to manage the limited resources effectively, use them equitably and in a sustainable manner. Third, because of their deep understanding of the local conditions, communities are always found to be in a better position to appreciate the possible options. Consequently, communities have been capable, in many cases, of making and putting in place, well-informed water resource management policies and strategies, which are accepted, supported and implemented by the communities themselves. And in that process, water resources come to be managed sustainably and water-use conflicts are minimized.

Community-based practices in management of water resources in Kenya have differed from place to place, reflecting the different physical endowment of water, cultural values and socio-political organizations of the concerned communities. In Machakos Sub-county, the Akamba community has dug ponds and terraced hillsides to such effect that today, despite a huge increase in population, their farms are producing more, the people are wealthier and their landscape is greener. This transformation has been called by researchers “the Machakos Mirracle”. This has been done mainly through harvesting rainwater as described by Pearce (2006); Tiffen et al. (1995).

have to be identified and assisted to participate fully in the process of developing the frameworks. Integrated catchment or watershed or river basin management approaches, that confer through policy and legislation, ownership and management roles to well-informed local communities will help to ensure the conservation and protection of the ecological water resources base, especially where large diffused populations in many rural areas rely directly on water resources for their subsistence.

It is worth noting that, after independence, many countries in Africa experienced a systematic shift towards the centralization of water management activities. This yielded limited positive results and many negative effects on resource management. Thus, there has been a re-emergence of a shift from the centralized management to a participatory approach which aims at involving stakeholders and communities in the whole process of water resources planning, development and management (Hirji et al., 2002). Since the current approach in water resources management is to involve stakeholders as much as possible, it is therefore appropriate that governments change their role from being implementers to being facilitators.

2.4. Participatory Approach in Kenya’s Water Sector Reforms

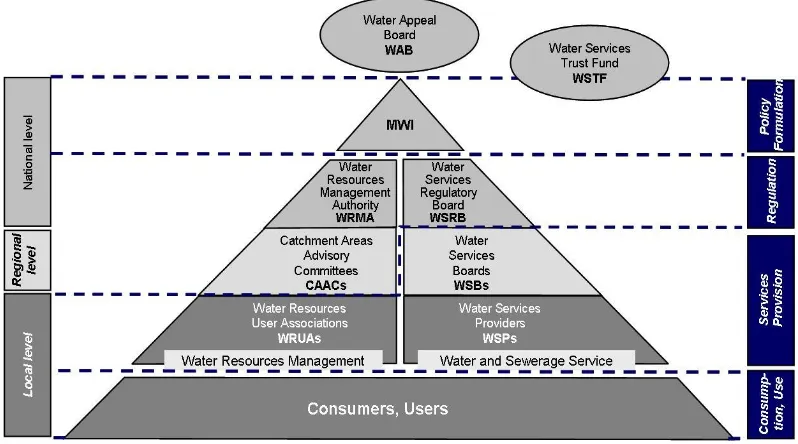

problems in the ministry. Thus, reforms came about through the Water Act, 2002 (Republic of Kenya, 2002). As part of the water sector reforms, the Water Act, 2002 created new institutions in order to separate the functions that were previously undertaken by the MWI. The policy changes that were brought by the Water Act covered the following areas: separation of functions; decentralization of functions from the headquarters down to the lowest level; community and private sector participation; and water to be considered as an economic and social good. To address the water resources problems, the Water Act, 2002 stipulated the development of the NWRMS. This was cascaded to regional and sub-regional levels. It emphasized a participatory approach that involved twelve institutions as key stakeholders in water resources management. Figure 2.1 shows the separationof functions brought by the Water Act, 2002.

Figure 2.1: Separation of functions in the Water Act, 2002 (WRMA, 2012, p 17).

Table 2.1: Roles and mandates of institutions created byWater Act, 2002 S/no. Institution Role

1 MWI To formulate policy and provide oversight

within the water sector 2 Water Services Trust

Fund

To finance Water Services

3 Water Appeal Board To hear and determine water disputes

4 Water Services

Regulatory Board

To regulate matters related to Water Services

5 Water Services Board Regional bodies responsible for regulation and planning for water services

6 Water Services Providers To provide water and sewerage services under license from WSB.

7 Water Resources Management Authority

To plan, regulate, conserve and manage Water Resources

8 Catchment Area Advisory Committee

Regional body set up to advice WRMA in management of Water Resources.

9 Water Resource Users Associations

Local body set up by water resource users to enable communities and stakeholders to participate in water resources management.

10 National Water

Corporations & Pipeline Company

Development and management of state assets for bulk water supply.

11 Kenya Water Institute Training and research development 12 National Irrigation Board Development of irrigation infrastructure. Source: WRMA, 2009, P 44

purposes of cooperatively sharing, managing and conserving a common water resource.

The Water Act, 2002 aimed at restructuring the water sector management and called for decentralization of functions to the lower level state organizations such as WRUAs and CAACs, and the involvement of non-governmental entities and community groups in the management of water resources (Republic of Kenya, 2002). According to Kenya‟s WRM Rules (Republic of Kenya, 2007c), protection of water catchments must involve all the relevant stakeholders and incorporate all pertinent information leading to important decisions for the integrated management of land, water and related biological resources. This promotes sustainable use of natural resources and improves the quality and quantity of water and the environment the water originates from. This approach is referred to as Integrated Catchment Management (ICM).

The participation of stakeholders in the context of WRUAs and CAACs makes water resource management more transparent and leads to better planning. Their involvement contributes to a demand-driven administration of water as a scarce resource and therefore leads to more equitable access (Musuva, 2010). As noted by WRMA (2009) the empowerment of the water users under the umbrella of WRUAs reduces violent conflicts over water resources and helps in addressing gender disparities in resource management.

resources including wetlands, rivers and lakes against disturbance by human activities.

The Ministry of Agriculture participates in water resources management as a key water using stakeholder. Through the Agriculture Act Cap 318 the Ministry of Agriculture defines the water courses and catchment areas in relation to crop and livestock production and related activities. As noted by WAC (2005), more than 40% of the country is ASAL and therefore there is insufficient water for irrigation which implies that water for irrigation has to be carefully managed for sustainability. Pearce (2006) noted that today 70% of all the water abstracted from rivers and underground is being used on the irrigated land that grows a third of the world‟s food. As a result, water, rather than land is the binding constraint on production on at least a third of the world‟s food today.

Kenya Forest Service (KFS) is instrumental in the ICM carried out by WRUAs since its main role is to promote tree planting and conservation of forests that are water catchment areas. The people of Machakos Sub-County have embraced the importance of tree planting which has helped to conserve water resources (Tiffen et al. 1995; Ogola, 1998; Musuva, 2010). TARDA is an authority which is mandated to advise the government on the institution and co-ordination of development projects in the area of Tana and Athi River Basins (TARDA, 2010). It deals mainly with catchment conservation.

2.5Challenges to Participatory Management of Water Resources

A study by the World Bank (1996) identified some factors that limit participation. The first is lack of government commitment to adopting a participatory approach. The other one is unwillingness of project officials to give up control over project activities and decisions followed by resistance of project level officials to share control with beneficiaries and other stakeholders. Also, lack of incentives and skills among project staff to encourage them to adopt a participatory approach accompanied by limited capacity of local-level organizations and insufficient investment in community capacity building. The others are starting participation too late and mistrust between government and local-level stakeholders.

Inability to understand the policy-making process was noted by Fisher and Magnnis (2008) as a challenge to community participation in projects. Where the policy-making process tends to be very complex, it is difficult for many community members to understand. Many community-based water projects have failed to succeed due to legal and institutional deficiencies which make management of water inefficient and expensive. Hirji et al. (2002), in a study in the SADC region identified the following challenges to participation in water resources management: inadequate consultations and representation in water resources management decision-making; inadequate representation of water users in water management institutions and participation of water users in water resources planning and management decision-making, and weak regulatory frameworks for water resources management.

seeking to gain political mileage. As pointed out by the PPIAF (2000), the governments of most countries have put in place monopoly utilities to run water supply and sewerage systems. This is because governments believe the nature of the infrastructure required, and the large economies of scale, mean these services are most efficiently operated by a single entity. However, publicly run utilities in developing countries have been singularly unsuccessful in providing reliable water supply and sanitation services. Most of them find themselves locked in a downward spiral of weak performance incentives, low willingness to pay by customers, insufficient funding for maintenance leading to deterioration of assets and political interference.

The recent trend in management of water sector towards privatization and deregulation of utilities, and increasing vulnerability due to the implications of climate change is a challenge. In some cases, privatization has occasioned the dismantling of important water resources and environmental regulations and legislation (Hirji et al., 2002). Political issues may also affect water resources management due to lack of leadership capacity at the local level. Splinter groups based on political inclination may emerge and weaken the bargaining power of the people. The wrangles that result may lead to political agitation to curb exploitation of the poor community members which may affect participation in water resources management projects. According to Dukeshire and Thurlow (2002), rural communities may lack access to resources such as adequate funding, government training programmes, education, and leaders to support rural causes and initiatives. This interferes with their ability to participate fully in development projects such as water resources management.

may create a barrier for the two to work together (Dukeshire & Thurlow, 2002). Lack of economic alternatives and sufficient support for basic needs may lead to destructive utilization of resources by communities (Fisher & Magnnis, 2008). Sometimes, the government may provide very short consultation period over projects which does not allow Community Based Organizations (CBO) time to research and prepare to participate effectively. In contrast, the policy-making process may take a very long time and exhaust the resources of CBOs thus frustrating them. Also, some community members may fail to understand that they are the indigenous custodians of resources which lead to destructive use of resources (Gathima, 2008).

Dukeshire and Thurlow (2002) highlighted four challenges that face policy makers and planners. The first is perceived resistance of communities as partners in policy development. This may arise from cultural identity of some communities and their failure to change their beliefs and traditions even where these changes could lead to their improvements. The community‟s attitude that the government has a responsibility to initiate projects for them may also pose a major challenge to the government. In Kenya‟s situation, this may affect community water resources management groups such as WRUAs, RRMAs and community water SHGs who could wait for the government to initiate and manage water projects for them.

Furthermore, projects created for urban centres may fail to fit in rural communities. Due to structural barriers, the government and the communities may lack opportunities to communicate with one another. CBOs may also lack opportunities to speak to government representatives around their policy concerns. Reliance on outdated water policies based on command and control approaches impedes participation in water resources management. In some regions, the concept of participatory water resources management is poorly understood by policy makers as well as water resource planners and managers. There is a wide disconnect between water managers and environmental managers, for instance, WRMA and NEMA in Kenya (Hirji et al., 2002).

As Cech (2010) noted, in future, the preservation of diverse ecosystems will be a challenge. Conflict will continue between the need to protect wetlands, riparian zones, and surface and groundwater quality, on the one hand, and the pressures to provide new housing, greater quantities of food, and sites for industrial and commercial expansion, on the other. Effective water resources management is a complex task and requires many and varied skills, a network of capable institutions and significant analytical capacity. Often well trained, water resources management professionals are commonly over-burdened, under-resourced and poorly compensated. They generally have limited access to professional associations, peer review, mid-career training, books and journals, and other professional incentives. There is need to develop greater capacity to be able to address the emerging issues (Hirji et al., 2002).

2.6. Strategies of Addressing Challenges in Participatory Water Resources Management.

innovative water resources management policies, legal and institutional reforms. Such reforms include the preparation of new water resources management strategies and river basin management plans and activities. Some of the reforms include innovative, environmentally sound water policies and provision of unique opportunities for sharing experiences. The water policy reforms offer a key opportunity for mainstreaming environmental considerations in the formulation of policy on water resources management, and in river basin planning and management. A good example is Kenya which has developed a new strategic plan covering the period 2012-2017 showing priority areas and strategies of addressing the emerging challenges (Republic of Kenya, 2012). In other countries, such as Namibia, a range of water demand management measures have been put in place. These include economic measures (water pricing), regulation, education and awareness-raising, technology improvements, water-loss control, water re-use and recycling (Hirji et al., 2002).

To address the problems faced by publicly run water supply utilities, PPIAF (2000) recommended a massive investment of time and political effort to: make institutional changes; improve policy; institute changes to the financial structure, including tariff; establish robust sector governance; and introduce more efficient and professional management of the utility. Public education, awareness and participation have been strongly advocated for. Fisher and Magnnis, (2008); WAC, 2005 noted that public participation in policy formulation instills a sense of ownership in the resultant policy and ensures commitment to implementation. Awareness about the principles of equitable sharing and allocation of water, sustainable use and principles of wise and economically efficient use of water are now gaining recognition.

communities have an intimate relationship with the catchment and their experiences can be integrated into the more scientific approaches to provide strategies for sustainable water resources management and environmental protection. The national water resources management policies and laws, particularly those of Kenya, South Africa, Tanzania and Zimbabwe, also propose strategies for awareness creation and training of stakeholders, and for mainstreaming gender equality issues in all aspects of water resources management. Communities need to be empowered to make informed decisions on water management and thus assist government to realize the global goals of strategic planning. Community level participation can be mobilized to deal with emergencies such as floods and extreme droughts. Community participation needs also to be incorporated into policy principles in order to support and promote integrated approaches to water resources management (Hirji et al., 2002).

A common measure of reform in the water resources management is bringing in the private sector to provide specialized expertise, efficient management and new sources of capital. In order for private sector participation to be possible, there is need for effective local government institutions which have a clear idea of the services they want and the extent to which they should be delegated to a private party. However, the private operator is expected to act in partnership with government, the regulator and other stakeholders. Further, improvements to the water sector governance and regulations must introduce greater transparency into the way prices are set (PPIAF, 2000).

This study intends to fill this gap by undertaking an assessment of the role of stakeholder participation in improving water availability through collaboration in water resources management in Machakos Sub-county. The contribution of various stakeholders in improving water availability was assessed based on the recommended Basic Water Requirement (BWR) of 50 litres/ person/ day for domestic water needs such as drinking, sanitation, bathing and cooking (Gleick et al., 2002; Kresic, 2009). It has been noted that in Africa per capita domestic water withdrawals are significantly below the BWR. Molden etal (2011) pointed out that Africa had to increase its total domestic water supply by 140% to reach the BWR. The ideas, measures and technologies that the stakeholders have used to address water resources management, as highlighted in the projects reviewed have been assessed in the context of IWRM bearing in mind the cross-cutting nature of water resources. The results of other related studies have also been used to strengthen and back the findings of this study where appropriate.

CHAPTER THREE: METHODOLOGY

3.1 Study Area

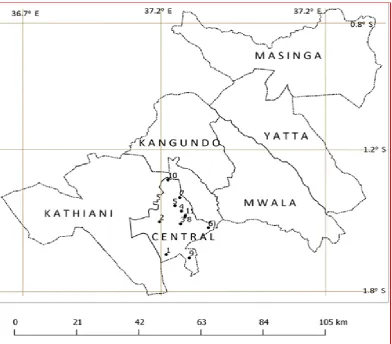

The study was carried out in Machakos Sub-county in Machakos County. The selection criteria was based on the fact that it horsts the headquarters of Athi Catchment Area which has the lowest per capita water in the country at 162 m3 without consideration of flood water and 356 m3 with flood water included. This catchment area falls in the category of „beyond the water barrier‟ since its water availability is less than 500 m3. It also has the highest total population of all the six catchment areas of Kenya at 16.7 million (WRMA, 2012). Out of this, Machakos Sub-county has 250,733 people spread in two administrative divisions, which is quite high (KNBS, 2009). The Sub-county comprises river and stream valleys in the catchment of Ikiwe River, south of Machakos town draining eastwards into the Athi- River system.

Legend of study sites

No. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Name Kakuyuni Kitanga Mbilini Lower Kiandani

Kamuthanga Kyanzasu Nduu

8 9 10 11

Mjini 15

Muumandu Kyaani Muputi

Figure 3.1: Map of Machakos County showing the location of the study sites

3.2. Climate

1435mm. Kyangala area has an annual rainfall mean of about 820mm since it is close to the hills. Rainfall distribution is bimodal with peaks in November and April. The first rains start normally at the end of March while the second rains start normally at the end of October. Rain bearing winds blow from the South-East. The short dry season is between January and March and occurs at the warmest time of the year. The long dry season of June to October has a cool period of about eight weeks associated with an almost continuous cloud cover (Musuva, 2010).

3.3. Hydrology

The main river draining the area is Wamui, also known as Ikiwe River. Wamui River catchment is part of the large Athi River drainage basin. The main tributaries to the river are Nzaini, Kyatololo and Miatha. The river is ephemeral and river flow is mainly during the rains. During the dry season the river bed is dry and characterized by exposed rocks and sand deposits in some sections. Wamui River joins with Makilu River and the name changes to Syuuni River. Wamui River valley runs North-West at an elevation of about 1500 metres. Other rivers in the Sub-county include Manza, Kyondu, Mwania, Vota, Wamaa, Kimutwa, Love, Yiini, Maluva, Mitheu, Miwongoni and Unyoleni. Most of these rivers are seasonal with shallow valleys (TANATHI, 2009

3.4. Research Design

management. A household survey was carried out to collect primary data using questionnaires. Interview schedules and observation sheets were also used. Secondary data was obtained through a review of books, scholarly journals and reports.

3.5. Population

The study targeted the various stakeholders who participated in management of water resources in Machakos Sub-county. These were classified into three categories. The first group comprised the water users at the community level who are recognized as the primary beneficiaries of decentralization of responsibility and ownership of water resources in a community (Hirji et al., 2002; Republic of Kenya, 2002; Republic of Kenya, 2012). A sample of 217 households was obtained to represent the community based on the criterion outlined in sub-section 3.6.1.The second category involved the policy makers and planners who formulated policies regarding water resources and oversaw policy implementation as outlined in the Water Act, 2002. These included WRMA, County Water Office (SCWO), Water Services Trust Fund (WSTF) and Water Services Regulatory Board (WSRB) among others. The third one was made up of water service providers in the Sub-County mainly Athi Water Services Board (WSB) and Machakos Water and Sewerage Company (MWSCO). The selection criterion was based on the principle of separation of functions outlined in the Water Act, 2002 (Republic of Kenya, 2002).

3.6 Sample and Sampling Procedure 3.6.1 Simple random sampling

respectively, were assigned random numbers. Each number was assigned a specific coloured ball. The balls were put in two separate boxes, one for each division. One ball was picked at a time without replacement and the sub-location recorded. This was done repeatedly until 9 sub-locations from central division and 2 from Kalama division were obtained (Mugera, 2011). The sample size for the households was calculated based on Bartlett et al (2001) formula:

n= z 2 pq/ d 2 , where;

n= required sample size,

z= Confidence level at 90% (Standard value of 1.65),

p= the proportion in the target population estimated to have characteristics being investigated (90%),

q= 1- p,

d= margin of error at 5% (Standard value of 0.05).

The calculation produced a sample size of 217 households. The number of selected households (HHs) was distributed proportionately in the 11 sampled sub-locations based on their density of households. Table 3.1 shows the sample obtained.

Table 3.1:Sampled sub-locations and households from Machakos Sub-county Division Location Sub-location No. of HHs Sample %

Central Township Mjini 15 3127 52 24.0

Muputi Muputi 655 11 5.1

Kimutwa Kyanzasu 541 9 4.1

Kiima Kimwe Mbilini 340 6 2.8

Mumbuni Lower Kiandani 2420 42 19.4

Katheka Kai Kitanga 734 12 5.5

Mutituni Nduu 683 11 5.1

Mua Hills Kyaani 251 4 1.8

Ngelani Kamuthanga 728 12 5.5

Kalama Lumbwa Muumandu 2087 35 16.1

Kalama Kakuyuni 1405 23 10.6

2 11 11 12,967 217 100

names of household heads were written on pieces of paper, put in a box and shuffled. Then random picking was done for each sub-location at a time until the sample was obtained.

3.6.2.Purposive sampling

As explained by Mugenda & Mugenda (2003) this is a technique which allows a researcher to hand pick cases that have the required information or characteristics according to the study objectives. This technique was used in selecting the Sub-County for the study. Machakos Sub-Sub-County was purposively selected based on the fact that it houses the regional headquarters of Athi Catchment basin which has the lowest per capita water endowment in Kenya at 162 m3, without flood water and 356m3 with flood water included (Republic of Kenya, 2012). Key informants from institutions involved in management of water resources based on the institutional framework outlined in the Water Act, 2002 (Republic of Kenya, 2002), were purposively chosen. These include WRMA, WSB, Sub-county Water Office, and CAAC. Other key stakeholder institutions including NEMA, TARDA, and KFS, were also purposively chosen. Community water SHGs and WRUAs which were involved in FGDs were purposively selected too. Two categories of focus groups were identified; one for the WRUAs and one for community-based water SHGs. FGDs were held on different dates as agreed with these groups. Purposive sampling was also used in selecting specific water resources such as Maruba Dam, the main source of water supplied by MWSCO and river Manza which feeds the dam; and community water points at Manza B, Mjini 15 and Kenya Israel were purposively chosen.

3.7. Data Collection Procedures

NEMA Office; TARDA; MWSCO; and CAAC (WRMA, 2009). The fourth level involved field visits to observe the purposively selected water resources. This aimed to find out the conditions of the water resources and how the various stakeholders were managing them. Secondary data was collected through examination of existing information on participatory water resources management. This involved some of the research findings from local sources and also foreign sources to find out what happens in and outside Kenya regarding stakeholder participation in water resources management. Research findings from international institutions such as IWMI, IAHS, GEF, WAC, FAO and IUCN which have done extensive research on water resource management were surveyed. Local research findings from individual researchers and institutions were also analyzed. Legal and policy documents of the Government of Kenya were also studied. These include: Water Act, 2002; Vision 2030; Sand Harvesting Guidelines, 2008; Wetlands Regulations, 2009; Water Quality Regulations, 2006, EIA Regulations, 2003 and Session Paper No. 1 of 1999.

3.8. Research Instruments

The following instruments were used to collect data:

1. Observation Record Sheets - were employed where the researcher was carrying out investigation on the types and condition of water resources and water resource management techniques that were being used by various key stakeholders (Appendix 4). They were used together with a digital camera to take photographs on the observed sources of water or stakeholders. 2. Household Interview Questionnaire -This was carried out in a structured

as recommended by Orodho (2008). This made the total 232 questionnaires.

3. Focus Group Discussion Guides- They were used to obtain information from groups involved in water resources management such as RRMAs, WRUAs, and SHGs. They captured data on water resources managed by the groups, group membership, water supply systems established by the groups, water resource management practices and techniques promoted by the groups and the challenges faced by the groups as well as the mitigation approaches they employed (Appendix 2).

4. Key Informant Interview Schedules - These were used to obtain information from institutions such as WRMA, NEMA, MWSCO, Sub-County Water Office and TARDA. These institutions are the key policy makers and planners of water resources in the Sub-County, whose input is crucial in influencing issues like water allocation, distribution and catchment conservation (Appendix 3).

3.9. Administration of Research Instruments

FGD guides, observation record sheets and KII schedules were filled by the researcher and research assistants during the interviews and field visits.

3.10 Data Analysis

The researcher used computer aided statistical packages mainly SPSS and Microsoft Excel to analyse the information collected. The completed questionnaires were examined for completeness. This was followed by coding of the responses for easy storage and analysis. The responses were then entered into the SPSS and Microsoft Excel to create data sets and data analysis commands were run. The analysis included both descriptive methods and inferential statistics. Descriptive statistics included frequency counts, percentages, mean and standard deviation. Pearson‟s Correlation Coefficient, t-test, Chi-square tests were used to establish the relationship between variables in accepting or rejecting the hypotheses. The minimum threshold for rejection or acceptance of H0 for this study

was set at p≤ 0.5 (Mugenda & Mugenda, 2003). The results obtained from data analysis are presented in form of frequencies, percentages and displayed in tables, pie charts, graphs, photographs and maps. The information obtained from FGDs and Key Informant Interview Guides was analyzed qualitatively and displayed using the same methods of data presentation.

3.11 Research Constraints

Traversing the expansive study area during data collection was the main constraint encountered due the cost and time required. Some of the sampled sub-locations such as Kyaani in Mua Hills, Kyanzasu in Kimutwa and Kakuyuni in Kalama Location are located in remote areas away from the main roads. Thus, reaching them involved use of motor cycles and even walking. This resulted in financial

constraint and fatigue on the part of the researcher and his assistants.