BAME Organ Donation 2014

behaviours s in the UK L REPORT epared for: Transplant epared by: a Research search.comGaining a deeper understanding of attitudes, cultural and lifestyle influences and towards organ donation within BAME communitie

FINA Pr NHS Blood and Pr Optimis www.optimisare

Contents

1

Introduction... 5

1.1.1 Key findings from the research ...5

1.1.2 Four key principles underpin any organ donation campaign...7

2

Background... 8

3

The project objectives... 11

4

Methodology ... 12

1. The ‘Explore and build’ stage ...12

2. Groups ...12

3. Depth interviews ...13

4. The ‘Measure’ Stage...14

5

Current attitudes to organ donation ... 17

6

Opportunities for behavioural change in organ donation... 29

7

Information and influence channels... 35

8

Driving a change in attitudes to organ donation... 38

9

Four key principles for any organ donation campaign ... 49

10

Conclusions... 51

11

Recommendations ... 53

12

Appendix ... 56

Table of Figures

Figure 1: Ethnic breakdown amongst religions based on 2011 Census data... 12 Figure 2: Sample structure of group discussions... 13 Figure 3: Sample structure of depth interviews... 14 Figure 4: Ethnic breakdown of interviews achieved versus 2011 Census data ... 14 Figure 5: Age profile of interviews achieved versus 2011 Census data ... 15 Figure 6: Proportion of interviewees stating a religion versus 2011 Census data... 15 Figure 7: Religious profile of interviews achieved versus 2011 Census data... 16 Figure 8: Support for organ donation in principle and willingness to donate own organs ... 17 Figure 9: Getting BAME audiences to talk about organ donation is a key challenge .... 19 Figure 10: Getting BAME audiences to talk about organ donation is a key challenge .. 20 Figure 11: Pakistani and Bangladeshi groups less likely to support organ donation in principle ... 22 Figure 12: Pakistani and Bangladeshi groups more likely to think organ donation is against religion ... 23 Figure 13: For Muslims, the influence of religion on decisions around organ donation is stronger than for other faiths... 24 Figure 14: Religious and cultural beliefs and traditions around death are passed down through generations... 26 Figure 15: The influence of family on key decisions... 28 Figure 16: Hindus, Sikhs and Christians are more likely to view organ donation as a personal decision... 28 Figure 17: Uncertainty around willingness to consider organ donation suggests some opening for discussion... 29 Figure 18: Support and consideration for organ donation by age... 30 Figure 19: Multiple channels likely to be consulted for more information on organ donation ... 31 Figure 20: The vast majority know nothing or very little about their own faith’s stance on organ donation ... 31 Figure 21: Key words used by followers of different religions in the sample to describe the central tenets of their faith ... 32 Figure 22: The importance of a local focus on charity ... 33 Figure 23: The most motivating statements tended to be individual not societal... 38 Figure 24: Guidelines for promotional messaging around organ donation... 39 Figure 25: Faith leaders’ video and posters from a New York campaign... 40 Figure 26: Prove It, Save Dave, and Would you take an organ? posters ... 40 Figure 27: Family stories and the ‘Pass it on’ video ... 42 Figure 28: Leila video, ‘Eyes campaign and organ donation poster... 42 Figure 29: Donate life, ‘’Hero’ and ‘Dustbin’... 43 Figure 30: The importance of specific ethnic references and respecting religious and cultural sensitivities ... 44 Figure 31: The ability of different messages to encourage or deter people from considering organ donation ... 46 Figure 32: The ability of different messages to encourage by ethnicity... 47Figure 33: Rank order appeal shows common appreciation for some of the same

messages ... 47 Figure 34: Rank order of appeal of messages combined with 4 key principles for a successful campaign ... 50

Executive Summary

1

Introduction

NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) is the Special Health Authority that manages the voluntary donation system for blood, tissues, organ and stem cells across the UK. As part of this remit NHSBT is also responsible for the NHS Organ Donor Register (ODR) which is a national, confidential list of people who are willing to become donors after their death. Despite significant increases in recent years in the number of people registering on the ODR, there is still a shortage of suitable organs and a large number of patients on the transplant waiting list.

As part of ongoing initiatives to increase organ donation rates a need has been identified to engage with Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities. This is vital because patients from BAME communities are more likely to need an organ transplant; a quarter of those on the waiting list are from a BAME background while representing just 12% of the UK population as a whole. This is because BAME communities are more vulnerable than non BAME communities to illnesses that can lead to organ failure. At the same time, 66% of people from BAME communities refuse permission for a family member’s organs to be donated. Organs are matched by blood group and tissue type (for kidney transplants) and the best‐matched transplants have the best outcome. Patients from the same ethnic group are more likely to be a close match. It is therefore critical that consent rates from BAME communities are increased.

Research conducted in 2013 by Optimisa Research as well as previous work conducted by NHSBT and other key stakeholders including the National Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) Transplant Alliance (NBTA) revealed a number of religious and cultural barriers within BAME communities towards organ donation. As a result, a need was identified to achieve a deeper understanding of these factors in order to inform future strategy for increasing donation and consent rates within these communities. Optimisa Research was engaged to conduct a programme of qualitative and quantitative research specifically with BAME audiences. This report sets out the findings of the 2014 BAME organ donation research.

1.1.1 Key findings from the research

Levels of support for organ donation in principle are much lower than in the general

population

44% of those surveyed support organ donation in principle, vs. 86% in the population as a whole in the 2013 research

28% say they would donate or consider donating their own organs vs. 82% in the population as a whole in 2013

3% say they definitely want to donate all or some of their organs vs. 51% in the population as a whole in 2013

This fundamental difference in attitudes towards donation appears to be driven by a number of contextual factors; low general awareness, knowledge and very low levels of debate or discussion, mistrust of the medical profession, perceived or assumed religious barriers, and a range of beliefs, traditions and practices around death.

Despite 85% of those surveyed saying that the subject of organ donation has never come up, only 6% say they have never discussed it because they would feel uncomfortable discussing it. This was confirmed by the qualitative research where it was clear that in many households organ donation has simply never been on the radar. It was also clear that there is an appetite for more information about the process, the particular implications of organ donation for BAME communities and the need for consent.

The qualitative research revealed some strong beliefs that organ donation goes against the teaching of some faiths; it was also clear that in some cases this was assumed rather than known to be the case, with many individuals saying that they simply didn’t know their faith’s position on the issue. What is clear is that cultural and religious factors are closely interwoven (particularly amongst Muslim communities), and that it is difficult for individuals to identify whether organ donation is uncommon because it is prohibited on grounds of religion or because it doesn’t fit with cultural practices.

There is potential for raising awareness and starting a dialogue about organ

donation

Despite some of the barriers uncovered by the research many individuals are unsure how they feel about organ donation and are open to learning more about it. Similarly, there appears to be scope for more clarity on the stance different religions have taken on the issue; 68% of Christians and 81% of Muslims say they don’t know how their religion views organ donation. Added to this, irrespective of the different levels of orthodoxy or devotion in the research, the qualitative research revealed a common desire to do good, to help others and to be a good member of the community. All of these factors suggest an opportunity to provide more information and open up

discussions on organ donation, allowing people to make an informed choice on their personal stance towards the issue. The importance of family and community suggests that this can best be done by boosting the scope and scale of the current outreach programmes, working within communities rather than from outside the community and encouraging discussion amongst the whole family unit.

Some of the tested messages have the power to motivate and alienate in equal

measure

A number of different marketing campaigns from around the world were tested in the qualitative research, and a range of communication messages were tested in the quantitative survey. The campaigns showed that targeted messages showing the positive outcomes and benefits of organ donation for families and communities are the most motivating while graphic portrayals of the shortage of organs can create negative feelings of pressure and guilt. Of the communications messages tested ‘One day it could be someone you know or love – or even you – in need of a transplant’ strongly resonated, with 72% feeling that this message would encourage them to consider and discuss organ donation.

1.1.2 Four key principles underpin any organ donation campaign

It is clear from the research that achieving behavioural change in organ donation, particularly among BAME audiences with the cultural and religious influences that need to be considered, need a gradual, step by step approach. This will help individuals to make an informed choice they are comfortable with and is likely to be the most effective way to proceed. The research identified 4 key principles that can be used to create a framework to underpin different campaigns and initiatives. While these can be applied with any target audience for organ donation, there are some specific considerations when working with BAME communities:

INFORM – address some of the knowledge gaps identified: the need for organs, the

importance of ethnicity in organ transplantation, consent, processes and procedures EMPOWER – give people the tools they need to seek out information and guidance from known, trusted sources and to make a personal choice ENCOURAGE – help communities to see the positive outcomes, benefits and wider consequences of organ donation INCLUDE – ensure that communications speak to the audiences they are aimed at: tailored, relevant and inclusive The remainder of this report provides more detail on all aspects of the research.

2

Background

NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) is the Special Health Authority that manages the voluntary donation system for blood, tissues, organ and stem cells across the UK. As such it ensures the safe, reliable supply of blood components, organs, stem cell and diagnostic services to hospitals in England and North Wales as well as providing tissue and solid organs to hospitals across the UK. As part of this remit NHSBT is also responsible for the NHS Organ Donor Register (ODR) which is a national, confidential list of people who are willing to become donors after their death. On average three people a day die in need of an organ transplant because there are not enough organs

available. There are currently around 7,000 people in the UK on the waiting list (this

figure changes constantly as people join and leave the waiting list), and many more in need of, an organ transplant.

The 2008 publication ‘Organs for Transplants’ from the Organ Donation Taskforce set out a number of recommendations for increasing donation rates and within these was an explicit recommendation to engage with Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities. This initiated the development of a range of educational and faith based materials, a number of public awareness campaigns and a calendar of BAME activities in collaboration with key stakeholders and in particular the NBTA. In May 2013 NHSBT hosted a ‘Faith and Organ Donation Summit’ which resulted in a number of recommendations from faith leaders.

According to NHSBT audit figures, 66% of people from BAME communities refuse permission for their loved ones’ organs to be donated. At the same time, patients from

BAME Communities are more likely to need an organ transplant than the rest of the

population as they are more susceptible to illnesses such as diabetes and

hypertension, which may result in organ failure. Organs are matched by blood group

and tissue type (for kidney transplants) and the best‐matched transplants have the best outcome. Patients from the same ethnic group are more likely to be a close match. 27% of patients waiting for a transplant are from a BAME background while BAME communities make up just 12% of the total UK population. It is therefore critical that consent rates from BAME communities are increased;

One consequence of the high refusal rate among BAME communities, and thus the

acute shortage of suitable organs, is that on average, patients from the BAME

communities will wait a year longer for a kidney transplant than a white patient.

While overall in the last six years the number of deceased organ donors has increased by 50%, this progress was driven by improvements in infrastructure and an increase in the number of families being asked to donate. The consent or authorisation rate (the percentage of families who, when asked, agree to donation), has remained broadly static.

Consent rates have a huge impact on NHSBT’s efforts to increase organ donation. In

the UK family refusal rates are among the highest in Europe at 45% for 2011/2012

compared with 19% in Spain and just under 5% in the Czech Republic. Given the

greater need for organs in the BAME population, it is vital that the refusal rate within

BAME families is reduced.

Taking Organ Transplantation to 2020 was published in July 2013 by the four UK

Health Ministers and NHSBT setting out the strategy to further increase organ

donation. It identified that a change in public behaviour is critical so that people

donate when and if they can and it becomes a normal and expected part of end of life

care. With little change in consent rates over the last six years the behaviour change

strategy has been developed based on quantitative and qualitative audience research

and an extensive audit of past and current public health behaviour change activity at a regional, national and international level. www.nhsbt.nhs.uk

The behaviour change strategy identifies three campaigning objectives:

To increase the number of people on the ODR by at least 50% by 2020 (from a

baseline of 20m in 2014), rebalancing it towards people who are from BAME

groups, older (50+) and from DE socio‐economic groups

To stimulate conversations and debate about donation, particularly through

leveraging the ODR as a marketing tool

To present donation as a benefit to families in the end‐of‐life and grieving process

The 2013 Optimisa research looked at multi‐faith and multi‐ethnic issues in the context of the UK population as a whole, with a proportion of the sample belonging to BAME communities. The research findings from these groups identified a need to look more closely at the cultural and religious factors influencing BAME attitudes to organ donation specifically. This need was endorsed in the Big Wins paper produced by the NBTA, which also highlighted in particular a need for more data on religion as a factor.

NHSBT subsequently engaged Optimisa Research to conduct qualitative and quantitative research specifically with BAME audiences to examine attitudes to organ

donation, the influence of religious and cultural factors on attitudes, and to explore in more detail any barriers to organ donation either personally or on behalf of loved ones.

3

The project objectives

The purpose of the research was ultimately to inform the development of NHSBT’s new behavioural change strategy for organ donation with particular regard to BAME communities. The learnings will facilitate the targeting and prioritisation of different groups within BAME communities and ensure that the messaging and channels used to reach out to these audiences are relevant, impactful and appropriate. One of the key stated aims of ‘Taking Organ Transplantation to 2020’ is for the UK to become a world leader in terms of its record for organ donation; the NBTA’s Big Wins paper (December 2013) highlights that increasing BAME awareness of the need to donate and putting the appropriate support in place to facilitate this within BAME communities will be critical in helping achieve this goal.

With this overarching goal in mind, the research set out to achieve a deeper understanding of two key areas;

1. BAME attitudes towards organ donation

2. The potential effectiveness of different channels in providing BAME communities with information about organ donation

In terms of exploring BAME attitudes towards organ donation the aim of the research was to build on the insight gained from the 2013 study. The research sought to explore some of the key themes from the previous research such as individuals’ willingness to join the ODR but not to discuss their wishes, and to identify any additional barriers and explore how these might be addressed, bearing in mind the role and influence of religious and cultural factors.

An equally important element of the research was to explore how best to equip BAME communities with the knowledge to make an informed choice about organ donation. In order to do this the research sought to understand

Usage of and preferences for TV, PR, radio, internet, advertising, word of mouth and events and which of these are recognised as being the most influential

The role of different local/community initiatives such as community groups, local newspapers/newsletters/magazines/radio, local events and activities including faith‐led activities and events at places of worship.

As highlighted in the campaigning objectives of the behavioural change strategy there is particular interest in the views of C2DE audiences who are currently under‐ represented on the Organ Donor Register. Accordingly, the qualitative research sample was designed to focus on these socio‐economic groups.

4

Methodology

The programme of research used to address the aforementioned research objectives fell into two key stages which have been brought together into one set of findings.

1. The ‘Explore and build’ stage

An initial qualitative approach was recommended to further explore attitudinal themes and awareness uncovered in the 2013 research before focusing on an exploration of different information channels. The qualitative stage and timings were designed to allow the findings to inform the development of the subsequent quantitative questionnaire.

A key consideration in designing the qualitative stage concerned who to speak to. With regards to religion, we knew from the 2013 research that the most resistance to organ donation was likely to come from Christians and Muslims since these were the groups where most concerns were expressed. The ethnic breakdown among these religions excluding white European and based on Census 2011 data is as follows:

Buddhist Christian Hindu Muslim Sikh

Asian/Asian British 90% 19% 97% 73% 89%

Black/African/Caribbean/ Black

British 2% 53% 1% 11% ‐

Mixed/multiple ethnic group 6% 23% 1% 4% 1%

Other ethnic group 2% 5% 1% 12% 10% Figure 1: Ethnic breakdown amongst religions based on 2011 Census data

For the qualitative stage, rather than attempting a nationally representative structure a more focussed approach was adopted, as seeking to cover all groups would not have been feasible in terms of time or cost. At the quantitative stage we aimed for a representative sample of ethnicities and religions across England; this is discussed in more detail in the quantitative ‘measure’ section below.

2. Groups

Given the exploratory nature of some of the objectives a focus group approach was recommended. While discussion groups are often avoided for researching potentially sensitive topics the 2013 research had shown that for BAME groups in particular ‘external’ factors such as religion, community and culture might be more influential for some than individual views.

In comparison to traditional groups of 8‐9 participants ‘midi‐groups’ of between 6‐7 individuals were convened to ensure respondents didn’t feel overwhelmed and were able to express themselves as much as possible. The structure of the groups was as follows:

Figure 2: Sample structure of group discussions

The sessions brought together individuals of a similar age, ethnic and religious background in a familiar or homely setting such as a local community centre or a recruiter’s home. This ensured individuals felt comfortable and relaxed, to allow for a free flowing and immersive discussion where, particularly in the community centres, we could also get an added feel for their environment. The groups were single gender to ensure no participants felt inhibited or obliged to defer to members of the opposite sex.

In total 14 x 90 minute discussion groups were conducted in Leeds, London, Oldham, Birmingham and Wellingborough. The research took place between 15th and 30th April 2014.

Participants were screened to ensure a mix of C2DE socio‐economic group, a range of attitudes to organ donation and a spread of more and less devout followers of their religion.

3. Depth interviews

In order to gain more in‐depth understanding of specific Muslim/Black communities and some ethnic groups that were not covered in the groups 12 x 60 minute depth interviews were conducted in Leeds and London.

Here the recruitment criteria sought to ensure that six of the twelve participants were on the organ donor register but had not spoken to others about it. This enabled the interviewers to gain additional insight around why they had not shared their decision to donate. The structure of the depth sample was as follows: 12 x 60 minute depth interviews Younger (18‐ 39 years) MALE Younger (18‐ 39 years) FEMALE Older (40‐65 years) MALE Older (40‐65 years) FEMALE

Pakistani Muslim 1 1 1 1 Bangladeshi Muslim ‐ 1 1 ‐ Somali Muslim 1 ‐ ‐ 1 Black African 1 ‐ ‐ 1 Black Caribbean ‐ 1 1 ‐ TOTAL SAMPLES 3 3 3 3

Figure 3: Sample structure of depth interviews

These sessions were conducted on a one to one basis in a location respondents felt comfortable in, such as their home, place of work or a local café.

4. The ‘Measure’ Stage

The measurement element of the study following on from the qualitative research took the form of an Ethnibus survey; a face to face omnibus among ethnic minorities where data is sampled and weighted to be representative of the BAME population in England, including region. For this study we spoke to five BAME audiences who had been identified by NHSBT as key populations to understand and research ‐ Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Black African and Black Caribbean. All data is therefore representative of these BAME audiences in accordance with Census data.

To be as inclusive as possible this face‐to‐face methodology was conducted using a specialist agency. A key benefit of this was that it used interviewers proficient in different languages who were able to speak to participants in their native tongue where appropriate. This ensured that the survey was as accessible as possible to the majority of potential respondents.

A total of 684 interviews were conducted during June 2014, among the following ethnic groups:

Ethnicity No. interviews % sample % Census 2011

Asian – Bangladeshi 55 10% 10%

Asian – Indian 237 35% 31%

Asian – Pakistani 152 22% 25%

Black – African 137 20% 22%

Black ‐ Caribbean 103 15% 13%

Figure 4: Ethnic breakdown of interviews achieved versus 2011 Census data

The interviews were evenly split by gender and those interviewed had a similar profile to the national population among these ethnic groups in terms of age, religion and proportion of first generation migrants.

Age

Our age profile was highly similar to the Census 2011 breakdown among the same ethnic groups:

Age % sample % Census 2011

18‐34 48% 44% 35‐54 38% 38% 55+ 16% 18%

Figure 5: Age profile of interviews achieved versus 2011 Census data

Religion

The Black Caribbean group in our sample tended to be more likely to state a religion compared with the same ethnic group in the 2011 Census, while the other ethnicities were broadly in line with Census data.

BangladeshiAsian – Asian – Indian Asian – Pakistani Black‐ African Black ‐ Caribbean

Sample Census OR Census OR Census OR Census OR Census % Stating

a religion (excluding not stated)

100% 99% 100% 97% 100% 99% 100% 97% 98% 86%

Figure 6: Proportion of interviewees stating a religion versus 2011 Census data

Among those stating a religion, the breakdown was broadly similar to the Census 2011 data. Our Indian respondents were more likely to be from Hindu communities, which may reflect the community based sampling approach. Indians/ British Indians are the most diverse in religious profile, but clustered communities tend to share a common faith. As the most widespread religion among this group, Indian communities in the UK are more likely to be Hindu, while other religious communities are sparser.

BangladeshiAsian – Asian – Indian Asian – Pakistani Black‐ African Black ‐ Caribbean

Sample Census OR Census OR Census OR Census OR Census

Christian 0% 2% 0% 10% 0% 2% 70% 77% 97% 96%

Hindu 0% 1% 85% 47% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

Muslim 100% 97% 2% 15% 100% 97% 30% 23% 0% 2%

Sikh 0% 0% 13% 24% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

Other 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 3% 2%

Figure 7: Religious profile of interviews achieved versus 2011 Census data

First generation migrants

Although slightly higher, the sample was similar to the 2011 Census in terms of the proportion of first generation migrants, with 62% saying they were born outside the UK (compared with 56% of those from comparable ethnic groups in Census 2011).

The core Optimisa Research team working on this project was Gemma Allen, Richard Fincham, Charlotte Jones, Cathy O’Brien, Julie Taylor and Sharron Worton.

Main Findings

5

Current attitudes to organ donation

Levels of support for organ donation in principle are much lower than in the general

population

It is clear that the high refusal rates seen in the BAME population relative to the population as a whole is underpinned by corresponding low levels of support for organ donation in principle and low willingness to donate or consider donating one’s own organs. In this research, 44% of those surveyed support organ donation in principle compared to 86% in the population as a whole in the 2013 research. Importantly, lower levels of support translate into lower levels of willingness to donate, with 28% saying they would or would consider donating their own organs compared to 82% in the population as a whole in the 2013 research. To break this down further, in the 2013 research 51% said they definitely wanted to donate all or some of their organs and a further 31% said they were willing to consider it. In the 2014 BAME research, just 3% say they definitely want to donate all or some of their organs with 25% saying they would consider it.

Figure 8: Support for organ donation in principle and willingness to donate own organs

Q08. Which of these statements best describes your views on organ donation after death? /Q12. Which of the

following describes how you personally feel about organ donation? Base: 684

In order to understand these figures better, we need to consider a number of contextual factors that are likely to be consciously or subconsciously influencing attitudes. A number of themes appear to be having an impact;

Low general awareness of organ donation resulting in very low levels of debate and discussion around the subject Mistrust of the medical profession and a lack of information about organ donation Perceived or assumed religious barriers to organ donation Religious/cultural beliefs, traditions and practices around death

Organ donation is very rarely on the radar for BAME audiences

While the influence of religious and cultural factors on attitudes cannot be underestimated, the key challenge is getting organ donation on the agenda. The overwhelming majority of those we spoke to in this research have never discussed organ donation before, with 85% reporting that the subject has simply never come up. This contrasts starkly with the 2013 research where just half of the general population sample said they had never discussed it and 44% said this was because the subject had simply never come up. Only 6% of the 2014 BAME sample state that they haven’t discussed organ donation because they wouldn’t feel comfortable bringing it up. It is likely that there is some ‘under claim’ here and that as we saw in the 2013 research the subject of death generally is taboo in many households, and may be exacerbated in some BAME communities either on religious/cultural grounds or out of respect for older family members.

“It [death] is a taboo in our culture. People don’t talk about it” Younger Male, Somali, Sunni Muslim

“I wouldn’t want to discuss it in front of my Nan. She’d get really upset. No‐one wants

to think about anyone dying do they?” Young female, Black Caribbean, Christian

“Donating our organs is just not something we do. I’ve never heard anyone talking

about it”

Older female, Bangladeshi, Muslim

“Organ donation? I don’t know a lot about it‐ it’s never really discussed. You kind of

know of it, but it doesn’t feel particularly directed at me” Younger female, Indian, Sikh

Discussion of organ donation is rare even among registered individuals

It is worth noting at this point that the lack of discussion of organ donation is not limited to those who have never considered it; in the qualitative discussions almost none of those on the ODR had discussed their wishes with anyone. Most were unaware of the consent process and therefore of the importance of discussing their wishes. Once aware, people often felt unsure of how they would approach the conversation; when should they bring it up, how should they position it, how could they handle objections or any distress caused? A minority felt resentful of the process, believing that they should not need to have their personal decision ‘endorsed’ by anyone else.

“I didn’t know I needed to discuss it. Why should I? It’s my body, and my right to do

what I want with it!”

Younger Female, Black Caribbean, Christian

This low awareness of the consent process is consistent with findings from the 2013 research, and an issue that needs to be addressed across the ODR. Even among the minority in the qualitative sample who were on the ODR and had discussed their wishes, awareness of the consent process was lacking. These individuals had discussed their wishes because organ donation had impacted on their families – one was an organ recipient, another the relative of a recipient and the subject was ‘out in the open’. As such their motivation for sharing was personal, not because they knew or thought they should share their decision.

A common characteristic here was a passionate belief in organ donation; it was clear from talking to them that they and individuals like them would make very good advocates for organ donation.

The figure below illustrates how rarely organ donation is discussed in BAME communities.

Figure 9: Getting BAME audiences to talk about organ donation is a key challenge

Q9. To what extent have you heard about or discussed organ donation after death? Q16. Have you, or has someone

you know ever needed an organ transplant? Base: 684

Mistrust of the medical profession and a lack of information about organ donation

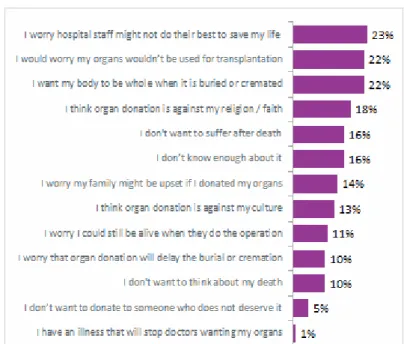

Mistrust in the medical profession was a key finding in the 2013 (general population) research and was, and continues to be, a key barrier among BAME communities. Almost a quarter (23%) were concerned that medical staff would not do enough to save their life, 22% that their organs might not ultimately be used for transplantation and 11% that they might still be alive when their organs were removed.

Figure 10: Getting BAME audiences to talk about organ donation is a key challenge

Q15. Which of these apply to you when thinking about whether you would consider donating your organs after

death? Base: 684

These concerns were echoed in the qualitative research, where in every discussion group at least one participant was able to relate a story of poor practice. There were some examples where people felt personally let down by the system; this was particularly evident in discussions with Pakistani and Bangladeshi males both young and old.

“This country’s medical department is very bad; I cry every night. The doctor sends me

for MRI, the results come in 5 days but my next appointment is not for a month” Older Male, Bangladeshi, Muslim

Other stories ranged from references to the 1999 investigation into organ retrieval at Alder Hey to more recent stories about patients lying for hours unattended in hospital corridors and others dying of dehydration. While these examples do not always involve organ donation and it is clear that many are anecdotal / driven by media coverage of ‘NHS scandals’, they illustrate a level of mistrust in the profession generally.

“There may be someone out there who has a better chance of survival than you have,

so they may think well we’ll just let her slip.” Younger female, Black Caribbean, Christian

Some first generation migrants are also influenced by their perceptions of organ donation in their home country, including stories of live donations in return for money, and of organs being taken after death without consent. While there were some views expressed qualitatively about the British health system being ‘better’ and more ‘trustworthy’ than in some other areas of the world, there was a sense that this may

be in recognition of the fact that there is access to free healthcare for all. Some of the participants in the qualitative research talked about access to healthcare being difficult or prohibitively expensive for family members ‘back home’; in this context any mistrust is balanced with a sense of gratitude or of being more fortunate than others. In any event, there is a clear need to address the issue of mistrust in the medical profession as part of any educational campaign around organ donation, both within BAME communities and in the population as a whole.

Lack of information about organ donation is another factor that is influencing attitudes and something that goes hand in hand with organ donation not being on the radar. 16% of those interviewed said that they didn’t know enough about the subject, compared to 11% of the general population sample in 2013. This became apparent very quickly in the qualitative discussions, where participants spontaneously thought of and started talking about living donation when the topic of organ donation was first introduced. The fact that organ donation is not understood when prompted and needs to be explained as ‘after death’ illustrates how effective positive stories about living donations have been, while positive stories about organ donation appear to be much thinner on the ground. It is unsurprising then that the majority of our sample say they have little or no knowledge of the subject.

“Everyone’s ignorant to it. I don’t know of anyone who ever needed it” Younger female, Pakistani, Muslim

“I should have researched this, that’s really bad” Younger Male, Somali, Sunni Muslim

Perceived or assumed religious barriers to organ donation

Across the 2014 BAME sample a number of major religions are represented and within these a range of levels of devotion and orthodoxy, from the very devout, ‘strict’ followers of their faith’s teaching through to those who are less devout, born into a faith but not really practising and lapsed. Irrespective of this, the research highlights some clear differences in attitudes to organ donation between Muslims and those of other faiths. Pakistani and Bangladeshi groups for example, predominantly Muslim by faith, are less likely to support organ donation in principle than people from predominantly non‐Muslim communities. Strikingly, many admitted in the qualitative discussions that they did not know their faith’s position and wanted some sort of consensus.

“I think it needs to be clarified. Scholars have got to tell us their opinion” Older Male, Bengali, Muslim

“Some Alims say yes, some say no – there is a lot of disagreement” Older Female, Bengali, Muslim

“If one says yes and one says no, I would go with what the majority say” Younger Female, Pakistani, Muslim

“For older generations there is a strong sense you should leave the world the way you

enter it. But I think that religion is how you want to see it and interpret it‐ it’s all

personal choice”

Younger Female, Indian, Sikh

Figure 11: Pakistani and Bangladeshi groups less likely to support organ donation in principle

Q08. Which of these statements best describes your views on organ donation after death? Base: 684

The qualitative research also suggests that religion is likely to be a key influencing factor for Muslims in particular, as it was noticeable in the discussions that many Muslims immediately and spontaneously thought about whether or not Islam allows or forbids donation, whereas for other faiths other factors such as personal concerns or generally mistrust of the profession were top of mind.

“I haven’t researched this, it’s just a feeling based on the idea of ‘qiyamat’ (afterlife)

and your obligation to Allah – you will be brought back to life (Resurrection Day)” Younger male, Somali, Sunni Muslim

“I’ve never really given it any serious thought. I don’t know enough about it” Older male, Black Caribbean, Christian

“It’s forbidden in our Islam. It’s in Hadith (reporting or teaching of the Sunnah in Islamic

tradition). It is forbidden”

Older Female, Pakistani, Muslim

The quantitative research supports this observation, with Pakistani and Bangladeshi respondents being particularly likely to think organ donation is against their religion compared to the ethnic groups predominantly representing other faiths such as

Hindus, Sikhs and Christians. Those in Pakistani communities were most likely to believe that organ donation is against their faith ‐ 36% stating this as a barrier. This is compared to 31% Bangladeshi and a significantly lower 11% Indian, 7% Caribbean and 15% African respondents. Figure 12: Pakistani and Bangladeshi groups more likely to think organ donation is against religion

Q15. Which of these apply to you when thinking about whether you would consider donating your organs after

death? Base: 684

Although the qualitative discussions uncovered some strong convictions about organ donation being against the teachings of some faiths, it was also clear that in many cases assumptions were being made; many participants admitted that they did not know for sure and would need to do some research or seek advice. It is here perhaps that religion and culture are most interwoven; there must be a reason why it doesn’t

happen, and maybe that reason is religion, maybe it is tradition. As discussed later in this report, this uncertainty and speculation when asked to think about the subject of organ donation suggests an opportunity to inform and educate. At the same time, the desire shown by many to avoid anything that is forbidden demonstrates how important it is for the major faiths to endorse organ donation.

“People are afraid of pain in the afterlife. It might not be religion but culturally it might

not be accepted. If everyone did it, everyone would be ok about it” Younger Female, Pakistani, Muslim

The likely influence of Islam on decisions around organ donation is clear when responses to the quantitative survey are broken down between Muslims and non‐ Muslims. While personal views on organ donation are very similar, Muslims are much

more likely to feel that their religion prohibits organ donation, and to say that religion will be a key influence on any decision they make about becoming a donor.

Figure 13: For Muslims, the influence of religion on decisions around organ donation is stronger than for other

faiths

Q08. Which of these statements best describes your views on organ donation after death? /Q12. Which of the

following describes how you personally feel about organ donation?/ Q15. Which of these apply to you when

thinking about whether you would consider donating your organs after death?/ Q6. Thinking about the following

situations, who would be most likely to influence the decision you make? Base: Non‐Muslim (431)/Muslim (253)

In contrast, the qualitative discussions with non‐Muslims uncovered more of a separation between religion and organ donation. Organ donation tended to be considered much more as a personal choice; non‐Muslims did not always feel they would need the endorsement of their faith in order to make a decision. In discussions with some devout non‐Muslims, for whom religion was more of a consideration, organ donation was felt to align well with their beliefs and the teachings of their faith; as such there was no expectation that a decision to donate would cause offence or have any other negative consequences.

“I can’t remember it ever having been discussed in my church but I would expect them

to see it as a personal choice, between me and God. I think most people at my church

would see it as a good thing.”

Older Male, Black Caribbean, Christian

“If Hindus are not donating I believe it is because of apathy, shyness and lack of

awareness, not because they don’t support it. They just need to be asked” Older Male, Indian, Hindu

“I don’t think there is anything in our religion that says you shouldn’t donate‐ I’ve never

heard anything. Obviously organ donation is relatively new and when the religion’s

started out no one knew about it then” Older Male, Indian, Sikh

A note on the Muslim sample in the research:

While many of the Muslims who took part in the quantitative survey felt their religion to be a barrier to organ donation, a feeling that was also very evident in the qualitative discussions, it was clear that this is underpinned by several other factors. Islam is seen by many as a way of life, more all‐encompassing than is evident in the relationship between non‐Muslims and their faith, and very much intertwined with culture and tradition within particular communities. The qualitative research in particular revealed that while many Muslims are seeking knowledge about Islam for themselves, and consulting those with greater perceived knowledge of Islam – as is common in Islamic culture – where less personal study is undertaken there appears to be more reliance on faith leaders and other sources of guidance for interpretation. This has implications for organ donation as decisions are likely to be made in consultation with other respected sources rather than in isolation. In addition, debate and discussion are frequently mentioned as being very important aspects of Islam, suggesting that there is the potential to start a dialogue about organ donation even where doors may initially seem to be closed.

Religious/cultural beliefs, traditions and practices around death

Across the qualitative research, irrespective of the level of devotion or orthodoxy demonstrated by participants of different faiths, the observance of long established practices and traditions around death is very clear. While many rituals and procedures have their roots in religious belief and/or teaching, and many families turn to (or sometimes back to) God when approaching death or in times of bereavement whatever their faith or religious upbringing, observing custom and tradition appears to be even more important within BAME families and communities.

For those born outside of the UK, upholding traditions is an important part of making sure that heritage is not lost or forgotten, and that family history is passed on and lives through second, third and future generations.

The impact of losing loved ones means that death and its rituals are almost sacrosanct in terms of the desire to uphold tradition. This is evidenced by the fact that while death is a taboo subject in many BAME households, many are well prepared for the eventuality and know exactly what arrangements need to be made should a family member pass away. It is unsurprising then that there is concern that organ donation could be disruptive. In essence, while this is an area of concern that needs addressing in the general population, it is important to keep in mind the particular implications for BAME audiences when seeking to encourage support for organ donation specifically within these communities. It is worth noting that in the case of Islam, the notion of death being taboo is somewhat at odds with the Islamic stance that death should be thought and spoken about freely, to encourage people to feel closer to their Maker, to pray and do good deeds, in the belief that they will be assured of a place in Jannah (heaven) in the afterlife. For many Muslims therefore it is not the subject of death itself that is difficult to broach, but rather the emphasis on after death arrangements.

The illustration below highlights some of the concerns raised in this research around organ donation and the traditions and customs surrounding death:

Figure 14: Religious and cultural beliefs and traditions around death are passed down through generations

Importantly, there are some clear differences in attitudes depending on whether the tradition in the deceased’s family is for burial or cremation. Where burial is ‘the norm’ there appears to be very often greater attachment to the physical form, leading many to express a desire or need to be ‘whole’.

“My body belongs to Allah Subhana T’ala (Allah, the most Glorified and Exalted); I want

to leave as I came into this world” Older Male, Pakistani, Muslim

“Your body should be as it was”

Younger Female, Black Caribbean, Christian

“After death there is nothing I can do. As a Muslim I am not allowed to give any part of

my body to someone”

Younger Male, Pakistani, Muslim

“Black people go with the Christian point of view. Stay as a whole, not taking bits away

from them which is given by God” Older Male, Black Caribbean, Christian

For some Muslims there is an additional consideration; a belief among some that the body continues to feel pain until it is buried (although it is unclear whether this is driven by religion or culture, and concerns about disfigurement / alterations to the

body and how this might impact on preparing/washing the body for burial and on those viewing the body before the funeral.

“In my religion we feel the dead body does still feel. When we wash a dead body, are

taught to be very delicate with them.” Younger Female, Somali, Muslim

In contrast, cultures and religions that favour cremation appear to have much less attachment to the physical remains of the deceased (their own or others’) and as a result do not feel that organs are ‘needed’ by the deceased person following death. This inevitably makes the notion of organ donation easier to contemplate. When this point of view is coupled with an assumption either that the family’s faith would endorse or at least not reject organ donation, or a belief that the decision to donate is a personal choice distinct from religious considerations, encouraging individuals to support or consent to organ donation will be less of a challenge.

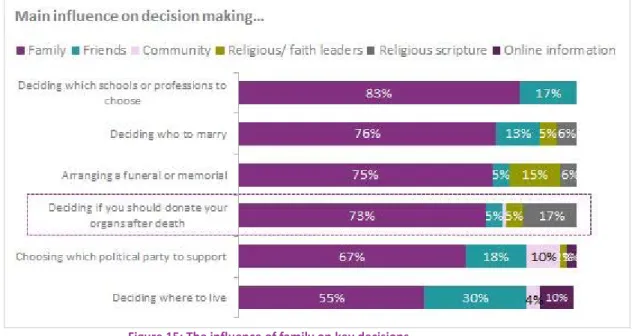

There is a fourth dimension to add to the influence that Faith, Culture and Knowledge have on BAME attitudes towards organ donation: Family. The importance of family is evident both in the qualitative discussions and in the quantitative sample where 14% of those surveyed cited being worried about upsetting family members when considering the idea of supporting organ donation. Across the whole BAME sample family was found to be a key influence, whether it surfaced as respect for the values and beliefs of elders or a desire to avoid upsetting older relatives. The deeper insight gained around BAME communities and family in this research helps us to understand why concerns about what the family may think is such an important barrier to overcome. The importance of family means that there is often greater focus on the collective than the individual, with the family at the heart of decision making. The closeness of the family structure means that values get passed down, together with cultural practices and tradition.

In some Muslim communities in particular there seems to be more adherence to tradition and customs than is the case in non‐Muslim BAME communities. Organ donation as a case in point is not customary for Muslims and can be seen as counter to tradition. Cultural norms such as respect for elders mean that (mainly younger) less observant Muslims will sometimes ‘shield’ older relatives from their own more relaxed views and behaviours. The observation of The 5 Pillars – the key tenets of Islam that are obligatory for all Muslims – is passed down to children as early as possible: Shahadah (The Pledge), Ramadan (fasting), Zakat (charity), Salaah (5 times a day prayer) and Hajj (pilgrimage). There is some sense that while younger members of the family may not always be as active as their elders, they rarely explicitly reject or distance themselves from Islam. Finding a way to ‘target’ the whole family – not just the elders, or younger family members – and get families talking will be critical to moving BAME organ donation forward. This is evidenced in the quantitative research where we can see the level of influence the family has across all BAME groups in a whole range of decision making areas:

Figure 15: The influence of family on key decisions

Q6. Thinking about the following situations, who would be most likely to influence the decision you make? Base:

684

Of the four broad areas of influence shown in the chart below, faith, family and culture all have the potential to discourage Muslims to consider supporting organ donation as things stand at present. For the most orthodox or devout, the influence of faith leaders is key; endorsement of organ donation locally and at a higher level would be transformative.

Within non‐Muslim families and communities, religion appears to be much less of an influence but culture and family hold a lot of sway. With religion as less of a barrier, there appears to be more potential for greater knowledge about organ donation to overcome cultural and familial considerations.

Figure 16: Hindus, Sikhs and Christians are more likely to view organ donation as a personal decision

6

Opportunities for behavioural change in organ donation

The contextual factors and influences at play in BAME communities are considerable but possible to address; the research has uncovered a number of indications that there is potential for raising awareness and having a dialogue that should encourage increased levels of consent and support for organ donation.

From this research we have been able to identify 4 opportunities to build support and engage with BAME communities:

1. Four in ten are unsure about their position on organ donation

Willingness to consider organ donation is not as straightforward as Yes or No – between a quarter and half of those surveyed were unsure. Combined with relatively strong support for organ donation in principle, and a further proportion ‘on the fence’, the biggest potential appears to be within Indian (Hindu/Sikh) communities:

Figure 17: Uncertainty around willingness to consider organ donation suggests some opening for discussion

Q12. Which of the following describes how you personally feel about organ donation? Base: 684

The picture is even more encouraging if we look at the total BAME sample by age. Around half of those aged between 18 and 34 say they support organ donation in principle, and are more likely than older age groups to consider donating their own organs:

“I wasn’t interested in this subject before but I am now” Younger Male, Pakistani, Muslim

“I was asked about joining [the ODR] when I changed doctors. It seems like a good

deed, a good thing to do. I won’t need them” Younger Female, Black Caribbean, Christian

“If there is any chance of it being acceptable in my religion then I would be happy to

consider”

Younger Male, Somali, Sunni Muslim

“None of these barriers are enough to put me off donating provided I knew enough

about it I just need to have a conversation with my family about it” Young Female, Indian, Sikh

Figure 18: Support and consideration for organ donation by age

Q08. Which of these statements best describes your views on organ donation after death? /Q12. Which of the

following describes how you personally feel about organ donation? Base: 684

2. An openness to discussing organ donation

The 2013 research established that many people feel they don’t know enough about organ donation to make an informed choice, and that when forced to make a decision the default or ‘safest’ decision is ‘No’. The 2014 BAME research highlights lack of information as a key barrier once again, but also tells us that there is some expectation that such a decision should be discussed and debated within family circles. Over half of those surveyed say they would turn to a family member to find out more about the subject. Around than 1 in 4 would seek out other information sources rather than speak to someone, and well over half of 18‐34 year olds would look online. This suggests an encouraging openness to further dialogue, but also emphasises the need for a multi‐channel approach.

Figure 19: Multiple channels likely to be consulted for more information on organ donation

Q11. Which of the following might you do if you were looking to find out more about organ donation after death

and whether your community or religion supports it? Base: 684

3. Very little visibility on religious stances on organ donation

Although religion is held up as a barrier, well over half agree that they don’t know their own religion’s actual position on organ donation; not surprising given that the overwhelming majority of those surveyed have never discussed the subject and cannot recall it having been discussed in the context of their faith. Over two thirds (68%) of Christians and 8 in 10 (81%) Muslims say they know nothing about how their religion views organ donation. While there was a lot of debate in the qualitative discussions surrounding the Islamic stance on organ donation, non‐Muslims appeared fairly confident that their faith would endorse it.

Figure 20: The vast majority know nothing or very little about their own faith’s stance on organ donation

Q10. Which of the following describes you? Base: 684

Lack of visibility of different religious stances ‘on the ground’ suggests that stronger, more faith‐specific messages could be useful for a) engaging undecided non‐Muslims