R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E

Open Access

Is HRQOL in dialysis associated with patient

survival or graft function after kidney

transplantation?

Nanna von der Lippe

1*, Bård Waldum-Grevbo

1,2, Anna Varberg Reisæter

3,4and Ingrid Os

1,2Abstract

Background:Health related quality of life (HRQOL) is patient-reported, and an important treatment outcome for patients undergoing renal replacement therapy. Whether HRQOL in dialysis can affect mortality or graft survival after renal transplantation (RTX) is not determined. The aims of the present study were to investigate whether pretransplant HRQOL is associated with post-RTX patient survival or graft function, and to assess whether improvement in HRQOL from dialysis to RTX is associated with patient survival.

Methods:In a longitudinal prospective study, HRQOL was measured in 142 prevalent dialysis patients (67 % males, mean age 51 ± 15.5 years) who subsequent underwent renal transplantation. HRQOL could

be repeated in 110 transplant patients 41 (IQR 34–51) months after RTX using the self-administered Kidney

Disease and Quality of Life Short Form (KDQOL-SF) measure. Kaplan-Meier plots were utilized for survival analyses, and linear regression models were used to address HRQOL and effect on graft function.

Results: Follow-up time was 102 (IQR 97–108) months after RTX. Survival after RTX was higher in patients

who perceived good physical function (PF) in dialysis compared to patients with poorer PF (p= 0.019). Low

scores in the domain mental health measured in dialysis was associated with accelerated decline in graft function (p= 0.048). Improvements in the kidney-specific domains “symptoms” and “effect of kidney disease” in the trajectory from dialysis to RTX were associated with a survival benefit (p= 0.007 and p= 0.02,

respectively).

Conclusion: HRQOL measured in dialysis patients was associated with survival and graft function after RTX. These findings may be useful in clinical pretransplant evaluations. Improvements in some of the kidney-specific HRQOL domains from dialysis to RTX were associated with lower mortality. Prospective and interventional studies are warranted.

Background

Patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD) may be treated with dialysis or renal transplantation (RTX). RTX is considered superior to chronic dialysis, as it prolongs survival and alleviates uremic symptoms [1, 2]. It is also considered more cost-effective based on quality adjusted life years [3]. Dialysis patients in Norway are considered with regard to eligibility for RTX, independent of chrono-logical age. During the last decades, short-term graft and patient survival have improved due to upgraded surgical procedures, more efficient immunosuppressive regimens

and improved care for complications and comorbidities. However, long-term term attrition rates for renal grafts have only shown small improvements, and survival in RTX patients is reduced compared to the general popula-tion [4–6].

Patient-related outcome measures (PROMs) have be-come important as they may capture the impact of disease perceived by the patients themselves. PROMs in a clinical setting are important for both the patient and the health provider as they may lead to more adequate intervention and treatment. The concept health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is an example of a PROM, and includes the subjective perception of e.g. physical function, mental well-being and social aspects.

* Correspondence:n.v.d.lippe@medisin.uio.no

1Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

Although aspects of HRQOL may improve after RTX compared with dialysis [7, 8], generic HRQOL is reported inferior by transplanted patients compared to that of the general population [1, 9]. Disease-specific HRQOL instru-ments may reveal other aspects of clinical importance than the generic tools, and unmask more subtle changes. Our group has recently reported that kidney-specific domains closely related to daily life complaints and nui-sances improved the most after RTX [9].

HRQOL has been shown to be a predictor of morbidity and mortality in dialysis patients, also after multiple adjustments [10–12]. In a large, prospective study by Mol-nar Varga et al. [13], poor HRQOL measured after RTX was associated with mortality and graft failure. These observations support that PROMS are important in the follow-up of RTX patients.

Whether self-perceived physical function reported during dialysis may be associated with mortality after renal transplantation has recently been addressed in two trials [14, 15]. Both reported that pretransplant physical function was associated to survival after RTX. Whether other aspects of HRQOL measured in dialysis could predict mortality after RTX has not been addressed.

Deteriorating renal graft function is associated with immunologic and non-immunologic factors, including reduced HRQOL measured after RTX [16–18]. Whether poor HRQOL during the time of dialysis may be related to graft function has not previously been addressed. Nor do we know whether improvement in HRQOL in the transition from dialysis to transplantation may be asso-ciated with survival.

We hypothesized that poor HRQOL during dialysis could be related to mortality and reduced graft function after RTX, and that patients with improvement in HRQOL from dialysis to transplantation had better survival com-pared to patients without improvement. Thus, the aims of our study were to explore whether generic or kidney-specific HRQOL measured during chronic dialysis was associated with mortality or graft function after successful renal transplantation. Secondly, to assess whether im-proved self-perceived HRQOL in the transition from dialy-sis to transplantation could be related to patient survival.

Methods

Between August 2005 and February 2007, a total of 301 prevalent dialysis patients from 10 different hospitals in Norway were included in a cross-sectional study address-ing HRQOL issues. The study details have been described previously, and are therefore only briefly presented here [19]. All patients >18 years receiving either hemodialysis (HD) or peritoneal dialysis (PD) for more than two months were invited to participate. Patients came from both rural and urban areas. Cognitive dysfunction, major psychiatric disorder and inadequate Norwegian language

skills were exclusion criteria. Hospitalization during the investigation period led to exclusion, but patients could be enrolled four weeks or more after hospital discharge if they were clinically stable. The questionnaires were answered by the patients during a regular HD session or during a scheduled visit for the PD patients.

In 2010–2011, a follow-up study was conducted, where patients who had taken part in the first study were invited to participate, whether they had undergone renal transplantation or were still in dialysis. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were unchanged from the previous study, except for the dialysis criteria. Transplanted patients completed the questionnaires during a regular visit at the renal outpatient clinic [9]. The present study provides results from transplanted patients only.

Clinical and demographical data were collected from hospital charts and/or direct questioning of the patients. Renal transplantation, graft function, patient survival, and cause of death were reported by the Norwegian Renal Registry [20]. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated on the basis of the simplified Modification of Diet in Renal Disease prediction equation [21]. Graft function was defined as eGFR. Comorbidity was mea-sured using the modified Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [22, 23]. CCI has been validated for dialysis patients [23] and kidney transplanted patients [24], and is a com-posite score of age and 19 weighted comorbid conditions, including coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, malignancy and chronic pulmonary disease. Diabetes as a comorbid condition scored one point, and diabetes as cause of ESRD scored two points. In the present study, CCI was also calculated without including age in order to enable evaluation of age as a separate variable in multivariate analysis.

HRQOL

patients and dialysis patients [27, 28]. In the present study, the item concerning dialysis access was not included in the KDQOL domain “symptoms”, as it is irrelevant for transplanted patients.

Half a standard deviation (SD) of the baseline score in each HRQOL domain was chosen as a measure of clinical relevant change in HRQOL from dialysis to RTX [29]. This is equivalent to Cohen’s d effect size of = 0.50 [30]. According Cohen’s d, an effect size of 0.2–0.5 is regarded a small effect, 0.5–0.8 a medium effect and 0.8 to infinity a large effect.

Statistics

Clinical and demographic data were presented as mean with SD if assumptions of normality were fulfilled, or as median with interquartile range (IQR) if data were skewed. Percentages were given for categorical variables. Dependent on the distribution of the variables, Student’st -test or Mann–WhitneyU test were used for comparison between two groups. Chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. The observation period for the survival analyses was defined as time from transplantation until death or study end (May 2015).

Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank statistics were ap-plied to identify significant differences in survival. Death (including death after return to dialysis) was defined as end point. All the KDQOL-SF domains were investigated regarding survival except “dialysis staff encouragement” and “satisfaction with care”, as these domains were con-sidered not relevant in transplanted patients. Based on pretransplant HRQOL scores, patients were categorized by tertile levels, and survival differences between the three patient groups were assessed.

Survival was compared between patients with clinical relevant improvement and patients with no clinical rele-vant improvement in the transition from dialysis to trans-plantation. The product term of age and HRQOL domains was entered in Cox regression analyses to check for inter-action regarding survival.

Multiple linear regression analyses were performed with yearly eGFR decline as dependent variable. 1-year post-transplant eGFR was used as the reference point for calcu-lating yearly decline, as eGFR levels might fluctuate during the first months after transplantation. For patients with graft loss, eGFR was set as zero the year they returned to dialysis. Patients who lost their graft or died within one year after transplantation were excluded in the regression analyses. Independent variables were age, gender, HRQOL domains, and comorbidity (CCI score without including age to avoid double adjustment for age). These variables were chosen on a clinical basis. The assumptions of linea-rity of continuous variables were checked and found to be adequately met.

Missing values in the generic part of KDQOL-SF were substituted with the patient’s mean score if less than half of the items were missing. No substitution was done in the kidney-specific part, if a question was left unanswered, the total score was calculated as suggested by the RAND group [25]. Missing data were treated by pairwise deletion in the statistical analyses.

All data were analysed using SPSS for Windows version 22 (IBM SPSS Statistics, New York, USA). Level of signifi-cance was set top< 0.05.

Results

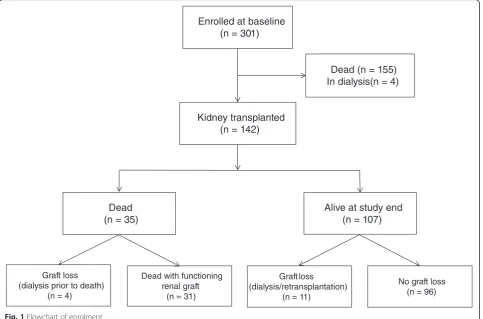

HRQOL measured in dialysis and survival

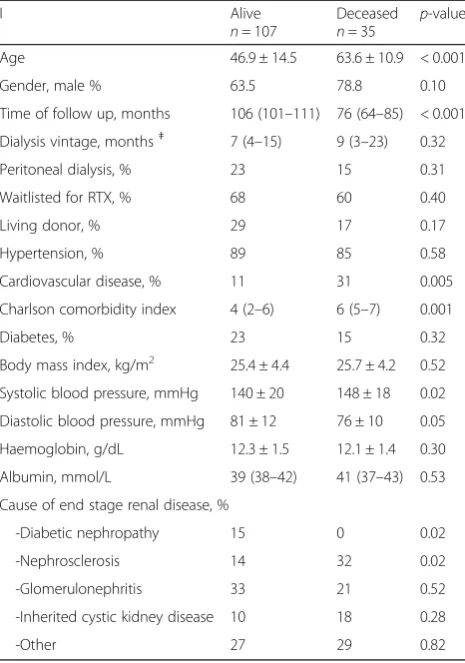

Of the 301 prevalent dialysis patients who had completed the HRQOL questionnaires in 2005–2007, 142 were sub-sequently transplanted (Fig. 1). Clinical and demographic characteristics are given in Table 1. The immunosuppres-sive regimen of cyclosporine/mycophenolate mofetil/ prednisolone was used in 43 %, while 39 % used a com-bination of tacrolimus/mycophenolate mofetil/prednisol-one. Median time from baseline to RTX was 11 (range 0–64) months, time from RTX to death or study end was 7.4 (0.8–9.7) years.

Differences in all-cause mortality after RTX appeared in the Kaplan-Meier survival plot between tertiles of patients with different scores of“physical function” mea-sured in dialysis (p= 0.063). The two upper tertiles (with the best physical function) were combined as the curves were close and different from the curve of those with the worst perceived physical function (Fig. 2). Five years after RTX, 88 % of patients with good physical function (the upper two tertiles) were alive, and 83 % of patients with poor physical function (the lower tertile). No inter-action between age and physical function was found (p= 0.38). Patient characteristics in the groups of poor vs. better physical function are given in Table 2. No other pretransplant KDQOL-SF domains were associated to survival after RTX.

HRQOL in dialysis and graft function

Within the first year post-RTX two patients died, one of them experienced graft loss prior to death, and another three patients lost their graft within one year. These patients were not included in the regression analyses regarding GFR decline.

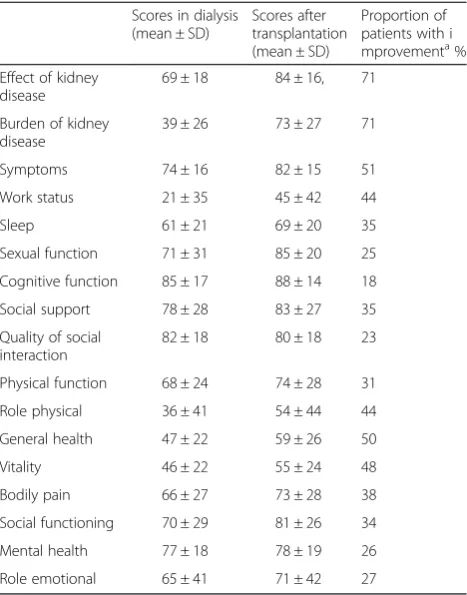

Change in HRQOL from dialysis to transplantation and survival

Of the 142 transplanted patients, 110 participated in the follow-up study, providing data of change in HRQOL scores from dialysis to RTX. Baseline KDQOL-SF scores (in dialysis) of these patients and the proportion with clinical relevant change from dialysis to RTX are given in Table 4. Reasons for not taking part in the follow-up study were exclusion due to mental deterioration or prolonged hospitalization (n= 19), death before follow-up (n= 5), returned to dialysis or still in dialysis at time of follow-up (n= 5) and unwillingness (n= 3). The patients participa-ting in the follow-up study did not differ in age, gender or comorbidity from those who did not take part, and the KDQOL-SF scores differed in two domains only, cognitive function (85 ± 17 vs. 74 ± 20, p= 0.001) and sexual func-tion (71 ± 31 vs. 54 ± 33p= 0.03) respectively.

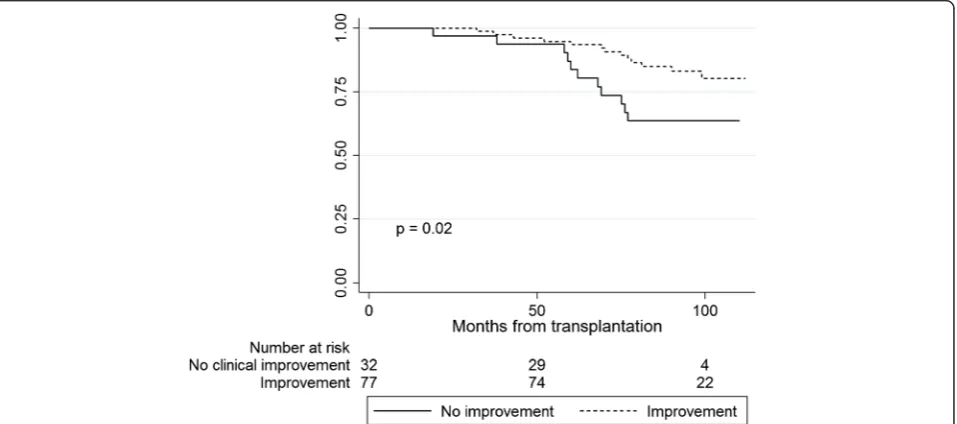

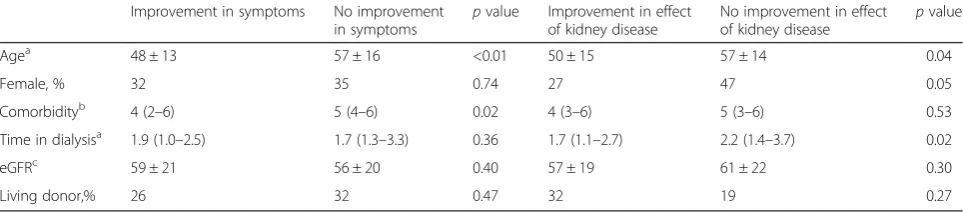

Kaplan-Meier curves revealed a survival advantage for patients with clinical relevant improvement from dialysis to transplantation in the HRQOL domains“symptoms”(p = 0.007) and“effect of kidney disease”(p= 0.02) compared to patients with no improvement or deterioration (Figs. 3 and 4). Five years after RTX, 96 % of the patients with improvement in symptoms were alive and 85 % of the patients with no improvement. For “effect of kidney

disease”, the proportion of patients alive after five years was 94 % amongst those with improvement, and 84 % for patients with no improvement. Patient characteristics of the groups with and without clinical relevant improve-ment in symptoms and effect of kidney disease are given in Table 5. There was no statistical interaction between age and“symptoms”(p= 0.15) or between age and“effect of kidney disease”(p= 0.40) in the Cox regression survival analyses. Changes in the generic HRQOL (SF-36) domains from dialysis to transplantation did not predict survival

Discussion

This prospective study is the first to address whether pre-transplant generic and kidney-specific HRQOL domains measured in dialysis were associated with survival after renal transplantation. That a single domain, i.e. physical function, obtained during dialysis could serve as an indica-tor of survival after renal transplantation, is an important finding with possible clinical implications for the pretrans-plant evaluation.

are also independently associated to survival [13, 17]. Only two studies have previously addressed whether HRQOL measured during dialysis could affect survival after trans-plantation [14, 31]. Kutner et al. [14] reported that poor pretransplant physical function affected the combined endpoint hospitalization and death six years after trans-plantation. As the number of deaths was very low, only five, the endpoint seemed driven mainly by hospitalization. That death rate was much lower than what has been reported in other transplantation registries [32–34]. The inclusion criteria in that study may have favoured younger and possibly healthier patients with short time in dialysis before RTX. Furthermore, contrasting the present study, 71 % of the patients had been treated with peritoneal dialysis suggesting a certain selection of patients.

During the preparation of the present manuscript, a large retrospective registry study from the US was published, including 10875 patients subsequently trans-planted [31]. Only the SF-36 domain “physical function” was investigated with regard to survival, and the authors concluded that poor functional status predicted 3-year mortality after transplantation. This is in accordance with our results from a much smaller cohort. In our prospective study, several other domains of generic and kidney-specific HRQOL were assessed with regard to survival. Thus, albeit small, the present study added new information, suggesting that the only KDQOL-SF do-main measured in dialysis that was associated to survival after RTX, was the physical function. The large US regis-try study [15] corroborated our findings that the effect of physical function on survival was not affected by age, as no interaction was found. Johansen et al. [35] suggested that frailty in dialysis patients could be assessed using self-reported physical function (SF-36) rather than cum-bersome objective testing. Frailty is a multidimensional Table 1Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in

dialysis (n= 142) who were subsequently renal transplanted. During follow up, 35 patients died

I Alive

n= 107

Deceased

n= 35 p -value

Age 46.9 ± 14.5 63.6 ± 10.9 < 0.001

Gender, male % 63.5 78.8 0.10

Time of follow up, months 106 (101–111) 76 (64–85) < 0.001

Dialysis vintage, monthsǂ 7 (4–15) 9 (3–23) 0.32

Peritoneal dialysis, % 23 15 0.31

Waitlisted for RTX, % 68 60 0.40

Living donor, % 29 17 0.17

Hypertension, % 89 85 0.58

Cardiovascular disease, % 11 31 0.005

Charlson comorbidity index 4 (2–6) 6 (5–7) 0.001

Diabetes, % 23 15 0.32

Body mass index, kg/m2 25.4 ± 4.4 25.7 ± 4.2 0.52

Systolic blood pressure, mmHg 140 ± 20 148 ± 18 0.02

Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg 81 ± 12 76 ± 10 0.05

Haemoglobin, g/dL 12.3 ± 1.5 12.1 ± 1.4 0.30

Albumin, mmol/L 39 (38–42) 41 (37–43) 0.53

Cause of end stage renal disease, %

-Diabetic nephropathy 15 0 0.02

-Nephrosclerosis 14 32 0.02

-Glomerulonephritis 33 21 0.52

-Inherited cystic kidney disease 10 18 0.28

-Other 27 29 0.82

construct describing vulnerability to various stressors [36]. The classic diagnostic criteria of frailty imbed both self-reported physical impairment and objective testing of muscle weakness. Frailty has been associated with disabi-lity, morbidity and mortality in older persons [36, 37]. Numerous dialysis patients suffer from severe neuropathy, myopathy and muscle weakness due to the kidney disease and possibly the dialysis treatment, explaining the high prevalence of frailty also in younger patients [38]. Comor-bidity also contributes to frailty, and we observed that patients with better self-reported physical function had less comorbidity in the present study. That frailty observed in patients while in dialysis may affect mortality even after they have undergone renal transplantation, needs to be confirmed in larger, prospective studies.

If a single domain in KDQOL-SF, physical function, measured in dialysis may predict survival after RTX, this could be of clinical importance as it might serve to iden-tify patients at increased risk after RTX. Furthermore, it may remind clinicians that physical activity in dialysis patients should be recommended as suggested in the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guidelines [39]. Self-reported physical activity has been shown to be associated with mortality and HRQOL both in dialysis patients and RTX patients [40, 41], but causality is not established and larger interventional studies are awaited.

Yet another exciting and novel finding in the present study was that the domain mental health measured in dialysis was associated with graft function after RTX, even after multiple adjustments. Actually, in the regression model, poor mental health in dialysis was the only variable that predicted an accelerated loss of graft function. That pretransplant scores in mental health predicted decline in graft function has not previously been addressed. How-ever, mental health as well as the mental composite score measured several years after transplantation has been shown to predict graft loss [13]. That effect on graft loss could not be confirmed in a later study of transplanted patients [17].

We have previously shown that there is surprisingly small changes in mental health from dialysis to transplan-tation [9]. Poor mental health is closely related to depres-sive symptoms [42, 43], which may increase the risk of non-adherence of immunosuppressive medication after transplantation [44]. Non-adherence in transplanted patients can be substantial [45], and enlarges the risk of graft failure [46]. Other factors contributing to accelerated graft decline in patients with poor mental health are likely Table 2Characteristics of patients (n= 142) with different

scores of“physical function”during dialysis Lower tertile physical function

Upper two tertiles physical function

pvalue

Agea 56 ± 14 50 ± 16 0.03

Female,% 34 32 0.64

Comorbidityb 5 (4–7) 4 (3–6) 0.02

Time in dialysisa 2.3 (1.5–3.5) 1.7 (1.1–2.5) 0.01

Albuminc 39.2 ± 4.4 39.6 ± 4.3 0.82

Living donor,% 17 32 0.06

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range as appropriate

a

At time of renal transplantation, in years;b

Charlson Comorbidity Index in dialysis;cIn dialysis, mmol/l

Table 3Linear regression model showing associations of yearly decline in graft function in kidney transplanted patients (n= 137)

Yearly GFRadecline, ml/min/1.73 m2

B p

Mental healthb, +10 points - 0.5 0.048

Agec,+10 years - 0.3 0.29

Gender, female 0,3 0.47

Comorbidityd, +1 point 0.4 0.32

a

Glomerular filtration rate. Higher values of yearly decline indicate more rapid loss of graft function from reference value one year after transplantation.

b

Mental health measured in dialysis.c

Age at time of transplantation.d

Charlson comorbidity index without adding points for age

Table 4KDQOL-SF scores in dialysis and after transplantation (n= 110) and the proportion of patients with clinical relevant improvementafrom dialysis to transplantationb

Scores in dialysis (mean ± SD)

Scores after transplantation (mean ± SD)

Proportion of patients with i mprovementa% Effect of kidney

disease

69 ± 18 84 ± 16, 71

Burden of kidney disease

39 ± 26 73 ± 27 71

Symptoms 74 ± 16 82 ± 15 51

Work status 21 ± 35 45 ± 42 44

Sleep 61 ± 21 69 ± 20 35

Sexual function 71 ± 31 85 ± 20 25

Cognitive function 85 ± 17 88 ± 14 18

Social support 78 ± 28 83 ± 27 35

Quality of social interaction

82 ± 18 80 ± 18 23

Physical function 68 ± 24 74 ± 28 31

Role physical 36 ± 41 54 ± 44 44

General health 47 ± 22 59 ± 26 50

Vitality 46 ± 22 55 ± 24 48

Bodily pain 66 ± 27 73 ± 28 38

Social functioning 70 ± 29 81 ± 26 34

Mental health 77 ± 18 78 ± 19 26

Role emotional 65 ± 41 71 ± 42 27

a

Improvement in score from dialysis to transplantation > 0.5 SD of the score in dialysis

b

numerous, including somatic, psychological, social and socioeconomic dimensions. Possible clinical implications of this finding should be closer follow-up of patients with low scores in mental health in dialysis.

We observed that patients with perceived clinical relevant improvement in the kidney specific domain “symptoms” and “effect of kidney disease” had a survival advantage compared to those without improvement. Comorbidity might have been a contributing factor. The domain“effect of kidney disease”encompasses questions about restrictions

in everyday life due to the kidney disease. Improvement could reflect the perception of returning to“a normal life” after transplantation.

Strengths and limitations

The prospective design, the representative cohort inclu-ding a third of the prevalent dialysis population at the time of investigation, and that none of the patients was lost to follow-up, were important strengths of the study. The quality of the data was good, with less than 1.5 % Fig. 3Kaplan-Meier plots showing survival of renal transplant patients with improvement vs. no improvement in“symptoms”from dialysis to transplantation

missing values in SF-36. Data on renal function and mortality were complete. The acceptance criteria for renal transplantation were based on national consensus. All transplantations in Norway were performed in one national center.

A limitation of the study was the size of the cohort and the number of events. Due to the inclusion criteria, only clinically stable patients without prolonged hospitalization during the inclusion period, severe cognitive dysfunction, psychiatric illness or drug abuse were included. This may have led to selection bias towards healthier patients. As the majority of patients were Caucasians, the applicability to other populations may be limited. The transplantation rate in Norway is high, the time in dialysis is short, and the dialysis population in Norway may therefore differ from other dialysis populations with less access to renal transplantation [20]. Causality cannot be determined, as the study design is observational. The likelihood of type 1 errors increases when multiple comparisons are per-formed without statistical adjustments. This study is observational and with a limited sample size, hence no corrections were performed to avoid omitting of impor-tant clinical findings. Thus, the findings should be inter-preted with caution.

Conclusion

Poor physical function measured during dialysis was associated with increased mortality up to seven years after transplantation. This finding might have clinical implica-tions. HRQOL measured in dialysis is a simple and time effective tool that could easily be included as a supplement to the pretransplant evaluation and particularly in recom-mendations with regard to physical function. Of clinical interest is also the finding that poor mental health in dialysis patients was associated to accelerated decline in graft function after RTX. Patients who perceive poor mental health in dialysis may need closer follow-up in the time after transplantation. Whether interventions to im-prove physical function and mental health in dialysis could

affect survival even after transplantation needs to be confirmed in larger studies.

Improvement in HRQOL in the transition from dialysis to transplantation seemed to indicate improved survival. This new finding needs to be addressed in future studies.

Abbreviations

CCI; Charlson Comorbidity Index; eGFR, Estimated glomerular filtration rate; EKD, Effect of kidney disease; ESRD: End stage renal disease; HD, hemodialysis; HRQOL, Health related quality of life; KDQOL, Kidney Disease Quality of Life; KDQOL-SF, Kidney Disease and Quality of Life Short Form measure version 1.3; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PROM, patient-related outcome measure; RTX, Renal transplantation; SF-36, Medical Outcome Study 36-item Short Form Health Survey.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for the collaboration of Torbjørn Leivestad, MD, PhD (Norwegian Renal Registry), and professor Leiv Sandvik, PhD, (University of Oslo) for assistance in statistical questions. Tone Brit Hortemo Østhus, MD, PhD, dialysis nurses and physicians at the ten participating hospitals (Oslo University Hospital, Innlandet Hospital Elverum and Lillehammer, Akershus University Hospital, Vestre Viken Hospital, Drammen, Vestfold Central Hospital, Stavanger University Hospital, Haukeland University Hospital, Østfold Central Hospital, and the University Hospital of North Norway, Tromsø) are measurement acknowledged for their work in collection of data. Without the participation of the transplanted patients, this study would not have been possible

Funding

The first author is research fellow and funded by the Institute of Clinical Medicine at the University of Oslo. Travel expenses associated with collecting the data at different hospitals were funded by research grants from the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting our findings are contained within the manuscript. According to the approval obtained from the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Norway and the hospital’s Human Research Ethics Committee, the data cannot be published or shared outside the hospital and research group.

Authors’contributions

NvdL has been involved in preparing the database, in cleaning data, she has participated in preparing the protocol which included the transplanted patients, she has prepared the manuscript, performed statistical analyses, and contributed in the discussion. BW has been co-supervisor, contributed in the discussion, overview the statistical analyses, and in editing the manuscript. AVR contributed to the discussion and edited the manuscript. IO has been main supervisor, has written the protocol, and contributed to the discussion and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Table 5Characteristics of patients (n= 110) with clinical relevant improvement vs. no improvement in the transition from dialysis to transplantation in the domains“symptoms”and“effect of kidney disease”

Improvement in symptoms No improvement in symptoms

pvalue Improvement in effect of kidney disease

No improvement in effect of kidney disease

pvalue

Agea 48 ± 13 57 ± 16 <0.01 50 ± 15 57 ± 14 0.04

Female, % 32 35 0.74 27 47 0.05

Comorbidityb 4 (2–6) 5 (4–6) 0.02 4 (3–6) 5 (3–6) 0.53

Time in dialysisa 1.9 (1.0–2.5) 1.7 (1.3–3.3) 0.36 1.7 (1.1–2.7) 2.2 (1.4–3.7) 0.02

eGFRc 59 ± 21 56 ± 20 0.40 57 ± 19 61 ± 22 0.30

Living donor,% 26 32 0.47 32 19 0.27

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range as appropriate

a

At time of renal transplantation, in years;b

Charlson Comorbidity Index in dialysis;c

Estimated glomerular filtration rate in ml/min/1.732

Authors’information

Nanna von der Lippe is a research fellow and a clinical lecturer at the Institute of Clinical Medicine at the University of Oslo. She is a specialist in internal medicine and is in training as a nephrologist at. Bård Waldum-Grevbo, MD, PhD, is an internist and nephrologist. He has previous held a position as post-doctoral fellow in the renal research group at Oslo University Hospital. Anna Varberg Reisæter, MD, DMSc, is nephrologist and head of the renal transplantation department at Oslo University Hospital. Ingrid Os, MD, DMSc is professor in nephrology and currently vice dean at the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Oslo. She is leader of the renal research group and is the main supervisor of the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Norway approved the protocol of the present study (reference number 2010/94), and concession was obtained from the National Data Inspectorate. The study was accomplished according to the Helsinki Declaration [47]. Written and oral information was provided, and informed signed consent was required.

Author details

1Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway.2Department

of Nephrology, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway.3Department of

Transplantation Medicine, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway.4The

Norwegian Renal Registry, Oslo, Norway.

Received: 10 February 2016 Accepted: 19 July 2016

References

1. Laupacis A, Keown P, Pus N, Krueger H, Ferguson B, Wong C, Muirhead N. A study of the quality of life and cost-utility of renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 1996;50(1):235–42.

2. Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, Held PJ, Port FK. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(23):1725–30.

3. Ferguson TW, Tangri N, Rigatto C, Komenda P. Cost-effective treatment modalities for reducing morbidity associated with chronic kidney disease. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15(2):243–52.

4. Lamb KE, Lodhi S, Meier-Kriesche HU. Long-term renal allograft survival in the United States: a critical reappraisal. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(3):450–62. 5. Meier-Kriesche HU, Schold JD, Srinivas TR, Kaplan B. Lack of improvement in

renal allograft survival despite a marked decrease in acute rejection rates over the most recent era. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(3):378–83.

6. Marcen R. Immunosuppressive drugs in kidney transplantation: impact on patient survival, and incidence of cardiovascular disease, malignancy and infection. Drugs. 2009;69(16):2227–43.

7. Kovacs AZ, Molnar MZ, Szeifert L, Ambrus C, Molnar-Varga M, Szentkiralyi A, Mucsi I, Novak M. Sleep disorders, depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life–a cross-sectional comparison between kidney transplant recipients and waitlisted patients on maintenance dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(3):1058–65.

8. Fujisawa M, Ichikawa Y, Yoshiya K, Isotani S, Higuchi A, Nagano S, Arakawa S, Hamami G, Matsumoto O, Kamidono S. Assessment of health-related quality of life in renal transplant and hemodialysis patients using the SF-36 health survey. Urology. 2000;56(2):201–6.

9. von der Lippe N, Waldum B, Brekke FB, Amro AA, Reisaeter AV, Os I. From dialysis to transplantation: a 5-year longitudinal study on self-reported quality of life. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:191.

10. Mapes DL, Lopes AA, Satayathum S, McCullough KP, Goodkin DA, Locatelli F, Fukuhara S, Young EW, Kurokawa K, Saito A, et al. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Kidney Int.

2003;64(1):339–49.

11. Osthus TB, Preljevic VT, Sandvik L, Leivestad T, Nordhus IH, Dammen T, Os I. Mortality and health-related quality of life in prevalent dialysis patients: Comparison between 12-items and 36-items short-form health survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:46.

12. Knight EL, Ofsthun N, Teng M, Lazarus JM, Curhan GC. The association between mental health, physical function, and hemodialysis mortality. Kidney Int. 2003;63(5):1843–51.

13. Molnar-Varga M, Molnar MZ, Szeifert L, Kovacs AZ, Kelemen A, Becze A, Laszlo G, Szentkiralyi A, Czira ME, Mucsi I, et al. Health-related quality of life and clinical outcomes in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(3):444–52.

14. Kutner NG, Zhang R, Bowles T, Painter P. Pretransplant physical functioning and kidney patients’risk for posttransplantation hospitalization/death: evidence from a national cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(4):837–43. 15. Reese PP, Bloom RD, Shults J, Thomasson A, Mussell A, Rosas SE, Johansen

KL, Abt P, Levine M, Caplan A, et al. Functional status and survival after kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2014;97(2):189–95.

16. Neri L, Dukes J, Brennan DC, Salvalaggio PR, Seelam S, Desiraju S, Schnitzler M. Impaired renal function is associated with worse self-reported outcomes after kidney transplantation. Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1689–98.

17. Griva K, Davenport A, Newman SP. Health-related quality of life and long-term survival and graft failure in kidney transplantation: a 12-year follow-up study. Transplantation. 2013;95(5):740–9.

18. Bohlke M, Marini SS, Rocha M, Terhorst L, Gomes RH, Barcellos FC, Irigoyen MC, Sesso R. Factors associated with health-related quality of life after successful kidney transplantation: a population-based study. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(9):1185–93.

19. Osthus TB, Dammen T, Sandvik L, Bruun CM, Nordhus IH, Os I. Health-related quality of life and depression in dialysis patients: associations with current smoking. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2010;44(1):46–55.

20. Annual Report 2014, The Norwegian Renal Registry [http://www.nephro.no/ nnr/AARSM2014.pdf]

21. Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a New prediction equation. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(6):461–70.

22. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

23. Beddhu S, Bruns FJ, Saul M, Seddon P, Zeidel ML. A simple comorbidity scale predicts clinical outcomes and costs in dialysis patients. Am J Med. 2000;108(8):609–13.

24. Jassal SV, Schaubel DE, Fenton SS. Baseline comorbidity in kidney transplant recipients: a comparison of comorbidity indices. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(1):136–42.

25. Hays RD, Kallich JD, Mapes DL, Coons SJ, Carter WB. Development of the kidney disease quality of life (KDQOL) instrument. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(5):329–38.

26. Ware Jr JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83.

27. Korevaar JC, Merkus MP, Jansen MA, Dekker FW, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT. Validation of the KDQOL-SF: a dialysis-targeted health measure. Qual Life Res. 2002;11(5):437–47.

28. Barotfi S, Molnar MZ, Almasi C, Kovacs AZ, Remport A, Szeifert L, Szentkiralyi A, Vamos E, Zoller R, Eremenco S, et al. Validation of the Kidney Disease Quality of Life-Short Form questionnaire in kidney transplant patients. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(5):495–504.

29. Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41(5):582–92.

30. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc: NJ; 1988.

31. Reese PP, Shults J, Bloom RD, Mussell A, Harhay MN, Abt P, Levine M, Johansen KL, Karlawish JT, Feldman HI. Functional status, time to transplantation, and survival benefit of kidney transplantation among wait-listed candidates. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(5):837–45. 32. 37th Report, Transplantation [http://www.anzdata.org.au/anzdata/

AnzdataReport/37thReport/c08_transplantation_print_20150929.pdf] 33. Reisaeter AV, Foss A, Hartmann A, Leivestad T, Midtvedt K. The kidney

34. Annual report on kidney transplantation, UK [http://www.odt.nhs.uk/pdf/ organ_specific_report_kidney_2014.pdf]

35. Johansen KL, Dalrymple LS, Delgado C, Kaysen GA, Kornak J, Grimes B, Chertow GM. Comparison of self-report-based and physical performance-based frailty definitions among patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(4):600–7. 36. Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the

concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(3):255–63. 37. Cawthon PM, Marshall LM, Michael Y, Dam TT, Ensrud KE, Barrett-Connor E,

Orwoll ES. Frailty in older men: prevalence, progression, and relationship with mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(8):1216–23.

38. Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Jin C, Kutner NG. Significance of frailty among dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(11):2960–7.

39. k/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Cardiovascular Disease in Dialysis Patients [https://www.kidney.org/professionals/guidelines/guidelines_ commentaries]

40. Lopes AA, Lantz B, Morgenstern H, Wang M, Bieber BA, Gillespie BW, Li Y, Painter P, Jacobson SH, Rayner HC, et al. Associations of self-reported physical activity types and levels with quality of life, depression symptoms, and mortality in hemodialysis patients: the DOPPS. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(10):1702–12.

41. Rosas SE, Reese PP, Huan Y, Doria C, Cochetti PT, Doyle A. Pretransplant physical activity predicts all-cause mortality in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35(1):17–23.

42. van den Beukel TO, Siegert CE, van Dijk S, Ter Wee PM, Dekker FW, Honig A. Comparison of the SF-36 Five-item Mental Health Inventory and Beck Depression Inventory for the screening of depressive symptoms in chronic dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(12):4453–7.

43. Preljevic VT, Osthus TB, Sandvik L, Opjordsmoen S, Nordhus IH, Os I, Dammen T. Screening for anxiety and depression in dialysis patients: comparison of the hospital anxiety and depression scale and the beck depression inventory. J Psychosom Res. 2012;73(2):139–44.

44. Jindal RM, Neff RT, Abbott KC, Hurst FP, Elster EA, Falta EM, Patel P, Cukor D. Association between depression and nonadherence in recipients of kidney transplants: analysis of the United States renal data system. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(9):3662–6.

45. Dew MA, DiMartini AF, De Vito DA, Myaskovsky L, Steel J, Unruh M, Switzer GE, Zomak R, Kormos RL, Greenhouse JB. Rates and risk factors for nonadherence to the medical regimen after adult solid organ

transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;83(7):858–73.

46. Denhaerynck K, Dobbels F, Cleemput I, Desmyttere A, Schafer-Keller P, Schaub S, De Geest S. Prevalence, consequences, and determinants of nonadherence in adult renal transplant patients: a literature review. Transpl Int. 2005;18(10):1121–33.

47. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki [http://www.wma.net/en/ 30publications/10policies/b3/17c.pdf]

• We accept pre-submission inquiries

• Our selector tool helps you to find the most relevant journal • We provide round the clock customer support

• Convenient online submission • Thorough peer review

• Inclusion in PubMed and all major indexing services • Maximum visibility for your research

Submit your manuscript at www.biomedcentral.com/submit