Is Noncompliance Among Adolescent Renal Transplant Recipients

Inevitable?

Sofia Feinstein, MD*; Rami Keich, MA*; Rachel Becker-Cohen, MD*; Choni Rinat, MD*; Shepard B. Schwartz, MD‡; and Yaacov Frishberg, MD*

ABSTRACT. Objective. To evaluate the prevalence of noncompliance and factors that influence poor adherence to immunosuppressive drug regimens among kidney transplant recipients.

Methods. We reviewed immunosuppressive drug compliance in 79 posttransplant patients. Patient self-report and low plasma calcineurin inhibitor levels served as indicators of noncompliance.

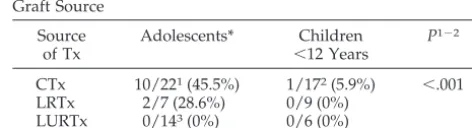

Results. The prevalence of noncompliance was found to be highest in adolescents who were responsible for their own medications and who underwent cadaveric kidney transplantation (CTx; 45.5%) and lower after liv-ing related transplantation (28.6%). There were no docu-mented cases of noncompliance among any recipient of living unrelated (commercial) transplantation. Among 13 noncompliant patients, the first indication of “drug hol-iday” was low plasma calcineurin inhibitor levels in 11 children. Two additional children presented with acute rejection. In 7 patients, repeated episodes of “drug holi-days” led to acute rejection later: 21.4ⴞ13.2 months after the first decrease in plasma calcineurin inhibitor level had been recorded. All 9 patients who experienced acute rejection subsequently developed chronic rejection. In 4 patients, noncompliance did not influence graft function. Psychosocial factors that were associated with noncom-pliance included insufficient family support, low self-awareness caused by poor cognitive abilities, and denial.

Conclusions. The absence of cases of noncompliance in adolescents who underwent commercial living unre-lated kidney transplantation suggests that although non-compliance is prevalent, it is not inevitable. Strategies to decrease noncompliance in young patients with chronic illnesses can be learned from the experience with trans-plant recipients. The general pediatrician has a central role in identifying and addressing the problem of non-compliance in adolescents with chronic disease.Pediatrics

2005;115:969–973;kidney transplantation, adolescents, com-pliance, chronic illnesses, commercial transplantation.

ABBREVIATIONS. Tx, transplantation; CsA, cyclosporine A; CTx, cadaveric kidney transplantation; LRTx, living related kidney transplantation; LURTx, living unrelated kidney transplantation.

I

nadequate immunosuppression is an important cause of rejection episodes in posttransplant (post-Tx) patients. Significant research is devoted to the development of new immunosuppressive medications, aimed at preventing rejection episodes and improving graft survival, yet many transplanted organs are lost as a result of noncompliant behav-ior.1–6Although noncompliance is common inmed-icine,7,8it is surprising that this phenomenon is also

prevalent among post-Tx patients, despite the high risk for consequent graft loss. We, as other pediatric nephrologists, have had experience caring for a num-ber of poorly compliant children but were not aware of the extent of this problem. Recently, we noted that a significant portion of late acute rejections in our post-Tx patients was caused by noncompliance with immunosuppressive therapy. This observation prompted us to undertake the following study. The aims were to evaluate the incidence of and factors that influence noncompliance in kidney Tx recipients and to determine their relationship to graft outcome.

METHODS

Medical records of 79 patients (46 boys and 33 girls) who underwent their first kidney Tx were reviewed. All patients were followed closely in our unit for at least 1 year.

Noncompliant behavior was defined as discontinuation of 1 or more immunosuppressive medications, deviation from prescribed dose or frequency, and/or “drug holidays.” Patient self report and/or cyclosporine A (CsA)/tacrolimus levels (CsA⬍20 ng/ml, tacrolimus⬍2 ng/ml) served as indicators of noncompliance.

The mean follow-up period was 4.8⫾2.7 years (range: 1–13). All children were followed at our unit during the predialysis period, while on dialysis, and after kidney Tx by the same team of pediatric nephrologists. Kidney Txs were performed in 2 centers in Israel or abroad. Fifty-one patients were of Arab descent, and 28 were Jewish. Data on the number of Txs, the source of the organ (cadaveric [CTx], living related [LRTx], and living unrelated do-nors [LURTx]), age at Tx, time on dialysis, and post-Tx follow-up are presented in Table 1. All LURTx were commercial Txs and were performed abroad (mostly in Iraq) at the parents’ initiative and against our advice, as this practice is illegal in Israel. Four patients underwent preemptive Tx. All but 2 patients received triple immunosuppressive therapy, including CsA/tacrolimus (41/36), mycophenolate mofetil/azathioprine, and prednisone. Nine patients included in the tacrolimus group were switched from CsA because of adverse effects.

Adolescents or young adults were included in this study when they were followed in our service for at least 1 year after their 12th birthday. The incidence of noncompliance after Tx was compared with the pre-Tx period in a subgroup of 53 patients who had been on dialysis for at least 6 months.

Routine follow-up for our post-Tx patients entailed twice-weekly visits during the first 3 months after transplantation, with a gradual decrease in frequency to a monthly visit after 1 year. Patients who missed their appointment to the clinic received a From the *Division of Pediatric Nephrology and ‡Department of Pediatrics,

Shaare Zedek Medical Center and Hebrew University–Hadassah School of Medicine, Jerusalem, Israel.

Accepted for publication Aug 5, 2004. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-0211 No conflict of interest declared.

Address correspondence to Yaacov Frishberg, MD, Division of Pediatric Nephrology, Shaare Zedek Medical Center, PO Box 3235, Jerusalem, Israel. E-mail: yaacov@md.huji.ac.il

telephone call from our team. Blood tests, including CsA/tacroli-mus levels, were drawn at each visit. None of our adolescent or young adult patients were transferred to an adult transplant unit. For the last 3 years, patients who received a transplant were also followed by a psychologist, who is a member of our team.

RESULTS

Noncompliance with immunosuppressive medica-tions was documented in 13 (5 girls) of 79 patients. Age at Tx was 13.6⫾4.8 years (SD) (range: 2.5–22.5), and the age when noncompliance was first recog-nized was 16.1 ⫾ 5.1 years (range: 6 –27). All but 1 patient were older than 12 years (Table 2). Two thirds of the patients demonstrated noncompliant behavior before Tx, while on dialysis. Among chil-dren with adequate post-Tx compliance, the fre-quency of poor drug adherence while on dialysis was significantly lower (Table 2).

The first indication of “drug holiday” in 2 of the 13 patients was an acute rejection episode (Table 3). In the remaining 11 children, it was low levels of plasma calcineurin inhibitors, with very mild (⬍20%) or no elevation of serum creatinine levels. In 7 of these 11 patients, repeated episodes of “drug holi-day” led to acute rejection later (21.4⫾13.2 months after the first decrease in plasma CsA/tacrolimus level). Noncompliant behavior with frequent “drug holidays” did not influence graft function in the re-maining 4 children for at least 32.3 ⫾ 16.8 months. Chronic rejection ensued in all 9 patients who devel-oped acute rejection. Three of them progressed to end-stage renal failure 3 to 7 years after the first indication of noncompliance. Three patients re-sumed taking immunosuppressive medications reg-ularly after the first episode of acute rejection. Others

continued with “drug holidays” and subsequently experienced repeated rejection episodes.

Noncompliance varied with graft source: it was highest (26.2%) among CTx recipients, lower after LRTxs (12.5%), and not documented in any patient after LURTx. The time from Tx to the first indication of noncompliance was 19.1⫾15.5 months in the CTx group and 20 and 48 months in the 2 patients from the LRTx group. In all 3 groups (CTxs, LRTxs, and LURTxs), there was a similar percentage of children above 12 years of age (Table 1). Most of these ado-lescents were responsible for taking their own med-ications. The prevalence of noncompliance among adolescents was 45.5% in CTx group, 28.6% in LRT group, and 0% in the LURTx group (Table 4). Only 1 of 17 children who were younger than 12 years and underwent CTx and none of the 15 children in the other groups was found to be noncompliant with immunosuppressive medications.

The prevalence of noncompliance was similar be-tween Jewish and Arab children (21.4% vs 13.7%), a consistent finding even when patients after CTx were evaluated separately (29.4% vs 30.0%). Gender, type of immunosuppression (CsA or tacrolimus), and du-ration of dialysis before transplantation did not affect the rate of low drug adherence (data not shown).

Noncompliance with nonimmunosuppressive medications (including antihypertensives, magne-sium and phosphorus supplements, and erythro-poietin injections) was much more common than with immunosuppressive medications: it was docu-mented in all patients who were noncompliant with immunosuppressive medications and in 10 addi-tional children.

Psychosocial Characteristics

We compared various personal and family charac-teristics between the compliant and noncompliant adolescents. There seemed to be an association be-tween the incidence of family crises (severe illness or death of a family member or divorce of parents) and noncompliant behavior, but this trend did not

TABLE 1. Characteristics of Post-Tx Patients Source of Tx No. of Patients No. of Adolescents (%)

Age at Tx, Mean, y⫾SD (Range)

Time on Dialysis, Mean, y⫾SD (Range)

Follow-up After Tx, Mean, y⫾SD (Range)

No. of Jews/Arabs

CTx 42 26 (60.4) 11.4⫾5.4 (2.5–19.0) 2.2⫾1.8 (0.1–9.0) 5.1⫾3.4 (1.0–13.0) 18/24

LRTx 16 7 (43.8) 10.9⫾7 (1.7–23.0) 0.9⫾1.4 (0–5.0) 5.2⫾3.4 (1.1–10.1) 7/9

LURTx 21 14 (66.6) 13.0⫾4.7 (2.9–19.5) 2.9⫾2.5 (0–6.2) 3.9⫾3.0 (1.0–10.0) 3/18

Total 79 28/51

P NS NS

NS indicates not significant.

TABLE 2. Characteristics of Noncompliant Post-Tx Patients Adolescents Pre-Tx

Noncompliance*

Jewish/ Arab

Noncompliant 12/13 (92.3%) 6/9 (66.7%) 6/7 Compliant 32/66 (48.5%) 6/44 (13.6%) 22/44

P ⬍.001 ⬍.05 NS

* More than 6 months on dialysis.

TABLE 3. First Indication and Outcome of Noncompliance First indication of noncompliance

Acute rejection 2/13

Low CsA/tacrolimus level 11/13

Consequent acute rejection 7/11

Outcome of noncompliance

Acute rejection, followed by chronic rejection

9/13

Resumed dialysis 3/9

Normal kidney function (32⫾18 mo) 4/13

TABLE 4. Incidence of Noncompliance in Relation to Age and Graft Source

Source of Tx

Adolescents* Children ⬍12 Years

P1⫺2

CTx 10/221(45.5%) 1/172(5.9%) ⬍.001

LRTx 2/7 (28.6%) 0/9 (0%)

LURTx 0/143(0%) 0/6 (0%)

P1⫺3 ⬍.01

achieve statistical significance (Table 5). Family sup-port was assessed by a psychologist and the medical team according to parents’ involvement in the pa-tient’s care (the frequency of accompanying the child to clinic, missing appointments, and providing the child with medications on time), as well as the mode of interaction between the child and his or her par-ents. Family conflicts, chaotic family style, chronic diseases of other family members, and psychosocial problems all could contribute to insufficient family support, which was significantly more common (P⬍ .001) in the noncompliant group.

Ten individuals had low self-awareness as a result of mild mental delay that required special education. Five of these adolescents who were responsible for their own medications and who seemed to be with-out adequate family support were noncompliant. Additional factors, including antisocial behavior, de-fined as having a criminal record or depressive symptoms that require antidepressants, did not seem to affect significantly the tendency of being noncom-pliant with immunosuppressive medications.

In the majority of noncompliant patients, 2 or more of the above-mentioned factors were noted. Psycho-logical interviewing revealed excessive denial in ap-proximately half of the noncompliant patients and fear of losing secondary gain in 1 patient of the same group. Denial not only served as a defense mecha-nism against anxiety and depression but also was associated with self-destructive behavior.

DISCUSSION

Noncompliant behavior in post-Tx patients may be a problem that is unique to adolescents who become independent enough to be made responsible for tak-ing their own medications. Durtak-ing this period, the risk for noncompliance and the consequent deterio-ration of graft function in kidney Tx recipients rises dramatically. The problem of poor drug adherence in adolescent patients has been described in other chronic diseases. For example, in asthma, the most common chronic illness of childhood,9noncompliant

behavior is particularly high in adolescents10,11 and

may contribute to the high level of morbidity and mortality in this age group.10Low compliance with

prednisone and antibiotic treatment was also found in half of adolescent outpatients with lymphoblastic lymphoma.12

For various psychological reasons, being an ado-lescent makes one more vulnerable and less ap-proachable. Teenagers with chronic illnesses realize that they remain different from their peers despite their continual effort to lead a normal life. These

existential issues bring about anxiety, and denial be-comes one’s worst enemy in a situation in which compliance is essential. These issues should be dis-cussed with each adolescent and his or her family individually, based on their cognitive and emotional level. Among the teenagers who were responsible for their own medications and followed in our service, the overall incidence of noncompliance was 26.2% compared with only 3% in children who were younger than 12 years.

There is wide variation in post-Tx noncompliance rate as recorded in previously published stud-ies.1,13–16This may be attributable to the use of

dif-ferent definitions and methods of assessment of non-compliance. Meyers et al15 found an overall

noncompliance rate of 22% with no difference in frequency between teenagers (11–15 years) and all other age groups. Blowly et al,16using an

electronic-monitoring device that detected access to medication containers, identified noncompliance in 21% of post-Tx adolescents. Watson17 reported a very high

noncompliance rate with consequent graft loss in 40% of adolescents and young adults after they had been transferred from pediatric to adult transplant units. A high rate of noncompliance was noted in our patient population despite that none of them was transferred to an adult unit.

The rate of noncompliance in patients who under-went CTx was a remarkable 45.5%. This figure may still underestimate the scope of the problem because our means of identifying noncompliance are limited. Noncompliance was suspected in cases of poor clinic attendance, absence of signs of steroid toxicity de-spite high prescribed doses, suboptimal control of hypertension, or unexplained late graft dysfunction. Low plasma CsA/tacrolimus levels were usually confirmatory of “drug holiday.” Adequate levels, however, do not exclude irregular use and may have merely reflected adherence to medications during the few days preceding testing. Patients with either low drug levels or declining renal function were questioned to elicit a report of compliance.

In most patients, an episodic decrease of plasma CsA/tacrolimus levels with stable renal function was the first indication of noncompliance. Acute rejection episodes occurred significantly later with a mean lag time of 21 months after the first sign of noncompli-ance. These episodes in turn led to gradual deterio-ration of graft function.

The exact dose required for adequate immunosup-pression varies between individual patients and is difficult to assess. Therefore, the recommended reg-imen is based on standard protocols. In 4 of 13

pa-TABLE 5. Psychosocial Characteristics in Post-Tx Adolescents Noncompliant

(N⫽12)

Compliant (N⫽32)

P

Family crises 6 8 NS

Insufficient family support 7 1 ⬍.001

Low self-awareness as a result of poor cognitive and behavioral abilities

5 5 NS

Responsible for their medications 5 0 ⬍.001

Antisocial behavior 3 0 NS

tients, graft function remained stable despite non-compliant behavior. This may suggest that the standard regimen may be excessive for individuals with some degree of tolerance. Preservation of renal function after discontinuation of immunosuppres-sants has previously been described.18,19

The Hartford Transplant Center group of investi-gators did not find in adults an association between the source of the organ (CTx or LRTx) and the ten-dency to be noncompliant.4,5In contrast, the majority

of our noncompliant patients were from the CTx group, and only 2 were from the LRTx group. All patients who underwent LURTx (commercial) were found to be adherent to their medications. This may suggest that financial considerations motivate pa-tients and their families to adhere to treatment. Al-ternatively, better compliance in the LURTx group may be attributable to better preparedness of the patient and his or her family for Tx, which is pre-ceded by a lengthy and arduous process including raising the necessary funds, planning a long trip abroad (which was the first of its type for all of the participants), and establishing connections with liai-sons in the health care chain, all in a clandestine atmosphere because of the illegality of commercial Tx. This requires initiative, persistence, and ample resources. It seems that parents who were capable of making a difficult decision to undergo LURTx and successfully pursued their initiative demonstrate similar abilities when strict adherence to therapeutic regimens is required and transmit this imperative to their children.

Individuals who undergo CTx, although cognizant of the procedure and its potential benefits, invest little of themselves as they await an unexpected tele-phone call and then are suddenly confronted with the availability of an organ for transplantation. Even the simple but potentially anxiety-provoking ques-tions of, “Who is the donor?” will be addressed only after surgery. The recipient will subsequently un-dergo a long process of adjustment to the new life-style, a vulnerable situation for the patients and their accompanying relatives. Suboptimal psychological readiness may lead to noncompliant behavior. Edu-cating adolescents who are awaiting CTx regarding the process that lies before them with emphasis on the virtue of medication compliance may have an impact on their post-Tx outcome. Participation of dialysis (pre-Tx) patients in a support group with post-Tx adolescents may help to crystallize the ben-efits of renal Tx and enhance the importance of drug adherence.

Wolff et al20suggested that noncompliance is

mul-tifactorial and should not be perceived solely as a fault of the patient. They claim that interaction be-tween patients and their care providers plays a major role in adherence to treatment plans. Our observa-tion that all of the children who underwent LURTx showed compliant behavior and had strong family support underscores the pivotal role of the cohesive-ness of the family in determining compliance. Drug adherence in young recipients similarly emphasizes the important role of the family. It should be noted that the families of children who underwent LURTx

received less support before Tx from the medical team, as they chose an illegal practice and therefore had to make the arrangements for Tx as well as face the moral dilemmas involved on their own. Living related kidney donors demonstrate altruistic behav-ior, which seems to be appreciated by the recipients as manifested in low rate of noncompliance. This is in contrast to families of children who undergo CTx, who display a passive attitude. The correlation be-tween family structure and noncompliant behavior should be addressed in a more systematic study. Although we object to the practice of LURTx, there are lessons that may be learned from this group of patients and applied to others to achieve better drug adherence. Our experience substantiates the notion that although noncompliance is prevalent, it is not inevitable.

How should the experience with renal Tx recipi-ents be applied to adolescrecipi-ents with chronic ailmrecipi-ents in general? A number of suggestions have already been proposed in the literature.8,13,21–24 These

in-clude increasing the frequency of clinic visits in sus-pected patients, reducing the number of nonessential drugs, using long-acting medications, inviting the truly responsible adolescent for follow-up without his or her parents, and being careful to provide rel-evant information based on the patient’s cognitive abilities. Reducing the dose of medications with po-tential cosmetic side effects, such as steroids, is im-perative. Our results suggest that children with even a mild cognitive deficit require continuous supervi-sion by a family member or caregiver. Transfer of medical care of noncompliant adolescents to adult units may result in deterioration of their health and should be conducted only once the patient is mature and psychologically prepared. The establishment of support groups for adolescents may have beneficial effects, especially if these are guided by a psycholo-gist. This will enable them to share without shame their unique medical experiences with their peers, as well as foster learning from one another of the health benefits of adhering to medications. Because individ-ual adolescents often seek to conform with their peers, support groups may be particularly effective in promoting compliance in this age group. Finally, we must utilize multidisciplinary resources and work creatively to better understand and improve communication between staff and families, as well as between patients and their parents. This underscores the role of the general pediatrician, who should be aware of the extent of noncompliance among adoles-cents with chronic illnesses and be able to detect early signs of this practice.

REFERENCES

1. Korsch BM, Fine RN, Negrete VF. Noncompliance in children with renal transplants.Pediatrics.1978;61:872– 876

2. Burke G, Esquenazi V, Gharagozloo H, et al. Long term results of kidney transplantation at the University of Miami.Clin Transpl.1989; 215–228

3. Dunn J, Golden D, Van-Buren CT, et al. Causes of graft loss beyond two years in the cyclosporine era.Transplantation.1990;49:349 –353 4. Schweizer RT, Rovelli M, Palmeri D, et al. Non-compliance in organ

5. Swanson MA, Palmeri D, Vossler ED, et al. Non-compliance in organ transplant recipients.Pharmacotherapy.1991;11:173S–174S

6. Hong JH, Shurani N, Delaney V, et al. Causes of late renal allograft failure in the ciclosporin era.Nephron.1992;62:272–279

7. Cramer JA, Mattson RH, Prevey ML, et al. How often is medication taken as prescribed? A novel assessment technique.JAMA.1989;261: 3273–3277

8. Wainwright SP, Gould D. Non-adherence with medications in organ transplant patients: a literature review.J Adv Nurs.1997;26:968 –977 9. Kaur B, Anderson HR, Austin J, et al. Prevalence of asthma symptoms,

diagnosis, and treatment in 12–14 year old children across Great Britain (international study of asthma and allergies in childhood, ISAAC UK). Br Med J.1998;316:118 –124

10. Price J, Kemp J. The problem of treating adolescent asthma: what are the alternatives to inhaled therapy?Respir Med.1999;93:677– 684 11. Buston KM, Wood SF. Non-compliance amongst adolescents with

asthma: listening to what they tell us about self-management.Fam Pract. 2000;17:134 –138

12. Festa RS, Tamaroff MH, Chasalow F, Lanzkovsky P. Therapeutic adherence to oral medication regimens by adolescents with cancer. 1. Laboratory assessment.J Pediatr.1992;120:807– 811

13. Beck DE, Fennel RS, Yost RL, et al. Evaluation of educational program on compliance with medication regimens in pediatric patients with renal transplants.J Pediatr.1980;96:1094 –1097

14. Ettenger RB, Rosental JT, Marik JL, et al. Improved cadaveric renal transplant outcome in children.Pediatr Nephrol.1991;5:137–142

15. Meyers KEC, Weiland H, Thomson PD. Paediatric renal transplantation non-compliance.Pediatr Nephrol.1995;9:469 – 472

16. Blowley DL, Hebert D, Arbus GS, et al. Compliance with cyclosporine in adolescent renal transplant recipients.Pediatr Nephrol. 1997;11: 547–551

17. Watson AR. Non-compliance and transfer from pediatric to adult trans-plant unit.Pediatr Nephrol.2000;14:469 – 472

18. Owens ML, Maxwell JG, Goodnight J, et al. Discontinuance of immu-nosuppression in renal transplant patients. Arch Surg. 1975;110: 1450 –1451

19. Uehling DT, Hussey JL, Weinstein AB, et al. Cessation of immunosup-pression after renal transplantation.Surgery.1976;79:278 –282 20. Wolff G, Strecker K, Vester U, et al. Non-compliance following renal

transplantation in children and adolescents.Pediatr Nephrol.1998;12: 703–708

21. Cochat P, De Geest S, Ritz E. Drug holiday: a challenging child-adult interface in kidney transplantation.Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15: 1924 –1927

22. Davis MC, Tucker CM, Fennel RS. Family behavior, adaptation, and treatment adherence of pediatric nephrology patients.Pediatr Nephrol. 1996;10:160 –166

23. Fielding D, Duff A. Compliance with treatment protocols: interventions for children with chronic illnesses.Arch Dis Child.1999;80:196 –200 24. Spinetta JJ, Masera G, Eden T, et al. Refusal, non-compliance, and

abandonment of treatment in children and adolescents with cancer.Med Pediatr Oncol.2002;38:114 –117

MASTER OF HYPOXIA

BAR-HEADED GOOSE

Migrates from India to Tibet, flying across the Himalayas at altitudes of up to 11 000 meters. There, oxygen levels are 20% of those at sea level—low enough to kill a human, but not the goose. While flying, it still has enough spunk left to honk, or so say delirious mountaineers who claim to have heard it.

LOIC LEFERME, freediver

Last year he descended to a world-record depth of 162 meters on a single breath of air. When freedivers like Leferme hit the water, their hearts slow by 50%, and their circulation shifts, lavishing most of their blood on the heart and brain.

Fox D.New Scientist. March 8, 2003

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2004-0211

2005;115;969

Pediatrics

Schwartz and Yaacov Frishberg

Sofia Feinstein, Rami Keich, Rachel Becker-Cohen, Choni Rinat, Shepard B.

Is Noncompliance Among Adolescent Renal Transplant Recipients Inevitable?

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/115/4/969

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/115/4/969#BIBL

This article cites 23 articles, 3 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/urology_sub

Urology

icine_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/adolescent_health:med

Adolescent Health/Medicine

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2004-0211

2005;115;969

Pediatrics

Schwartz and Yaacov Frishberg

Sofia Feinstein, Rami Keich, Rachel Becker-Cohen, Choni Rinat, Shepard B.

Is Noncompliance Among Adolescent Renal Transplant Recipients Inevitable?

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/115/4/969

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.