GENERAL PEDIATRIC RESEARCH

Black and White Middle Class Children Who Have Private Health

Insurance in the United States

Michael Weitzman, MD*; Robert S. Byrd, MD, MPH‡; and Peggy Auinger, MS*

ABSTRACT. Objective. To compare the health, be-havior and school problems, and use of medical, mental health, and special education services of privately in-sured, middle class black and white children in the United States.

Design/Methods. Analyses of the Child Health Sup-plement to the 1988 National Health Interview Survey, with a nationally representative sample of 17 110 chil-dren age 0 –17 years.

Results. Privately insured middle class black chil-dren had fewer chronic health conditions, but were less likely to be reported to be in excellent health (46.2% vs 57.3%) and more likely to have had asthma (8.5% vs 5.8%) or to have been of low birth weight (10.7% vs 5.6%). There were no differences in rates of having a usual source of routine care (92.2% vs 93.8%) or of being up to date with well-child care (79.3% vs 78.2%), but black children made fewer physician visits, were less likely to use physicians’ offices, were more likely to lack continuity of care, and were twice as likely to use emer-gency departments. These differences in use of medical services persisted in multivariate analyses and analyses restricted to more affluent children. Despite similar rates of behavior problems, black children were more likely to repeat a grade (20.0% vs 12.3%) and to have been suspended from school (11.3% vs 5.0%). Although significantly fewer black middle class children received mental health or special education services in bivariate analyses, no differences in receipt of these services were noted in multivariate analyses. All differences reported were significant.

Conclusions. Among middle class children in the United States, black and white children have similar rates of health and behavior problems, but black chil-dren experience substantially increased rates of asthma, low birth weight, and school difficulties. Al-though not differing in the receipt of mental health or special education services, middle class black chil-dren, even in the presence of private health insurance, have markedly different sources and patterns of use of medical services.Pediatrics1999;104:151–157;black and white children, middle class, private health in-surance.

ABBREVIATION. BPI, Behavior Problem Index.

S

ubstantial time and resources have been

de-voted to identifying, attempting to

under-stand the causal mechanisms behind, and

rectifying racial disparities in health in the United

States.

1–10Much of our understanding of racial

dif-ferences in children’s health and access to health

services has been hindered by black race being

confounded and often confused with low

socioeco-nomic status,

4,9,11,12and we often fail to recognize

that

.

50% of all black children in the United States

do not live in poverty.

In contrast to the extensive literature comparing

the health and use of health services of poor and

nonpoor children

13–18or of uninsured and insured

children,

19virtually no literature has focused on

these issues for middle class black and white

chil-dren. The objectives of this study were to

investi-gate and compare the health, behavior and school

problems, sources of ambulatory care for, and use

of medical, mental health, and special education

services of middle class black and white children

with private health insurance in the United States.

These children were the focus because private

in-surance is the primary means of financing health

care for children in this country,

20and we wished

to examine the health and patterns of service use

among children for whom there are no, or minimal,

financial barriers to care.

METHODS

Data were from the Child Health Supplement to the 1988 National Health Interview Survey. This is a cross-sectional, ran-domized household survey conducted by the Bureau of the Census for the National Center for Health Statistics.21,22In se-lected years, the most recent being 1988, a Child Health Sup-plement is added to obtain detailed information about the health of and use of health services by the nation’s children. Informa-tion was obtained by face-to-face interviews with adult family members on 1 randomly chosen child per household surveyed, resulting in a sample of 17 110 children 0 to 17 years of age, representative of all noninstitutionalized children and youth in the United States in 1988.

The Census Bureau does not have an official definition of the “middle class,” but it does rank households from lowest to highest based on income and then divides them into equal population groups, typically quintiles. The lowest quintile often is used as a proxy measure of those in poverty and the highest quintile as those who are most affluent.23For the purposes of these analyses, children were categorized as being middle class if their families’ reported income was in the second, third, or fourth quintile. In 1988, family incomes in the second quintile

From the *Department of Pediatrics, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, New York, and the ‡Department of Pediatrics, University of California School of Medicine at Davis, Davis, California.

This work was presented in part at the 37th Annual Meeting of the Ambulatory Pediatric Association; May 1997; Washington, DC. Received for publication Dec 26, 1998; accepted Feb 4, 1999.

Address correspondence to Michael Weitzman, MD, Department of Pedi-atrics, Rochester General Hospital, 1425 Portland Ave, Rochester, NY 14621. E-mail: michael.weitzman@viahealth.org

ranged from $15 103 to $26 182, in the third quintile from $26 183 to $38 500, and in the fourth quintile from $38 501 to $55 906. Therefore, children in middle class families, as defined in these analyses, were in families whose incomes ranged from $15 103 to $55 906 in 1988. The comparable range in 1995 was $19 071 to $72 260. Because of concern that comparisons using children in families whose incomes are in the second through fourth quintiles might be biased because of the unequal distri-bution of black and white children across this income range, all bivariate analyses were repeated after analyses were restricted only to children in families whose incomes were in the third and fourth quintiles.

Children were categorized as being covered by private health insurance if the respondent answered yes to the question, “Is — now covered by a health insurance plan that pays any part of a hospital, doctor’s office or surgeon’s bill?” Although this ques-tion may be answered affirmatively by some children covered by Medicaid, such misclassification is likely to be minimized with the analyses limited to children whose family income is above the poverty level. Demographic and family characteristics, health status, behavior and school problems, and sources of ambulatory care and utilization of health services of privately insured, middle class black and white children and youth were compared, as presented below.

Demographic and Family Characteristics

Characteristics investigated included family income and size; region and degree of urbanization of residence24,25; maternal educational level and age at the time of child’s birth; single- or two-parent family; and index child’s age and gender. As is true of all other variables in this dataset, children’s race was based on parental report. Race and Hispanic ethnicity were asked sepa-rately. Hispanic children were not excluded from analyses, and racial comparisons in this study are likely to be less pronounced than in analyses confined to non-Hispanic children.

Health Status

The following aspects of children’s physical health were in-vestigated: parental rating of children’s overall health; the per-centage of children whose birth weights were low and very low (2500 and 1500 g, respectively) or who were reported as having asthma; the prevalence of chronic physical health conditions (ascertained from affirmative responses to a checklist of 76 childhood health conditions that respondents were asked whether the child had in the past 12 months— 68 of which were considered chronic, consistent with earlier work using the sur-vey)19,21,26,27; limitations of activities among children reported as having any of these chronic conditions; and the number of days spent in bed.

Behavior and School Problems

Extreme scores (top 10th percentile) on the 32-item Behavior Problem Index (BPI) developed by Zill for children 4 years of age and older and modeled after the Child Behavior Checklist of Achenbach and Edelbrock28,29were used to identify the percent of children who had behavior problems. This index has been used in several earlier studies,30 –35and extreme scores on it have been shown to correlate substantially with referrals to mental health professionals.30Whether the respondent believed that the child needed psychological help in the past year also was de-termined, as was whether the child had ever repeated a grade or been suspended from school.

Utilization of Medical, Mental Health, and Special Education Services

Sources of routine and sick care and whether the child uti-lized the same source for routine and sick care (continuity of routine and sick care) were assessed. Sources of care were cat-egorized as 1) physicians’ office (doctors’ offices, private clinics, and health maintenance organization/prepaid group plans); 2) outpatient clinics (hospital, school, and migrant clinics); 3) health centers (neighborhood and rural centers); and 4) emer-gency departments (hospital emeremer-gency departments and walk-in emergency care centers). Also investigated were the number of visits made to a physician, the number of hospital-izations in the past 12 months, and whether the child was up to

date for well-child care,19estimated by comparing the reported number of routine physician visits with age-specific guidelines established by the American Academy of Pediatrics.36Also as-sessed was whether the child had ever seen a psychiatrist or counselor or received special education services. No detailed information regarding the specific nature of special education services received was available, thus, it was not possible to determine whether parents were referring to educational coun-seling, tutoring, or other school-based support services, or to their children being placed in totally separate classes or educa-tional tracks.

Statistical Analyses

x2Tests were used to test for differences in weighted propor-tions. Logistic and linear regression modeling was conducted to investigate the independent association of children’s race and aspects of their physical health, behavior and school problems, sources of ambulatory care, and utilization of services.

All analyses were conducted on an IBM-compatible PC. PC SAS software was used for the initial analyses.37SUDAAN soft-ware was used to obtain precise confidence intervals, account-ing for the complex, two-stage survey design.38

RESULTS

Of the

;

64 million children in the United States

in 1988, 48.3% (4.3 million) of black and 67% (32.5

million) of white children lived in families whose

incomes were in the second, third, and fourth

quin-tiles of family incomes (

P

,

.001). Of these middle

class children, 75.9% of black and 85.3% of white

youth had private health insurance (

P

,

.001). All

subsequent results and all tabular presentations of

data refer to middle class children who were

re-ported to have had private health insurance.

Demographic and Family Characteristics

Among middle class children who had private

health insurance, black children were less affluent

and more likely to live in single-parent households

(31.3% vs 12.4%;

P

,

.001) of larger size (3.62 vs

3.34 family members per household;

P

5

.003) with

mothers whose age at their birth was

#

16 years

(3.6% vs 1.4%;

P

,

.01) (Table 1). Maternal

educa-tional status did not differ between groups.

Physical Health, Behavior, and School Problems

Black children were reported as having fewer

chronic health conditions, fewer days in bed

be-cause of illness, and comparable rates of limitations

of activity. However, they were less likely to be

reported to be in excellent health (46.2% vs 57.3%;

P

,

.001) (Table 2). They also were more likely to

have been born with a low birth weight (10.7% vs

5.6%;

P

,

.001) and to have asthma (8.5% vs 5.8%;

P

,

.01).

Whereas there were no differences in rates of

scoring in the top 10th percentile on the BPI or in

being perceived by parents as needing

psychologi-cal help in the past 12 months, black children were

almost twice as likely to have ever repeated any

grade (20.0% vs 12.3%;

P

,

.001), and they were

more than twice as likely to have ever been

sus-pended from school (11.3% vs 5.0%;

P

,

.001).

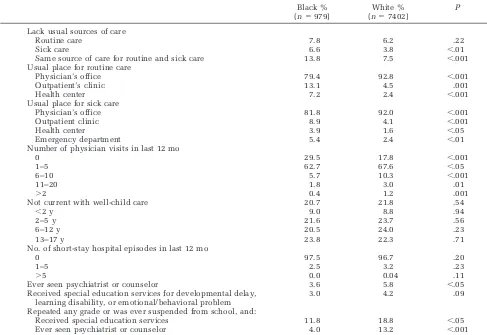

Utilization of Medical, Mental Health, and Special Education Services

were no differences in rates of being up to date with

well-child care or in the number of hospital

epi-sodes in the past 12 months, on every other

mea-sure, the two groups differed (Table 3). Black

chil-dren lacked a source for sick care (6.6% vs 3.8%;

P

,

.01) or continuity of routine and sick care more

frequently (13.8% vs 7.5%;

P

,

.001), used a

phy-sician’s office for routine (79.4% vs 92.8%;

P

,

.001) or sick care (81.8% vs 92.0%;

P

,

.001) less

frequently, and were more than twice as likely to

have used emergency departments for sick care

(5.4% vs 2.4%;

P

,

.01). They also made fewer

ambulatory care visits, were less likely to receive

mental health services (3.6% vs 5.8%;

P

,

.05), and

among children who repeated a grade or were

sus-pended from school, they were substantially less

likely to have received special education (11.8% vs

18.8%;

P

,

.05) or mental health services (4.0% vs

13.2%;

P

,

.001).

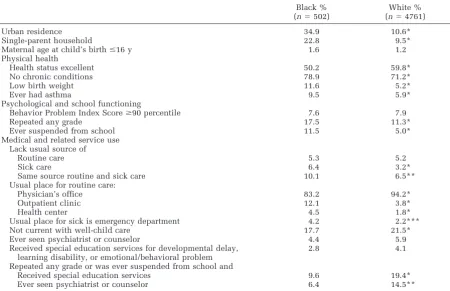

Children Whose Family Incomes Were in the Third and Fourth Quintiles

Analyses restricted to children whose family

in-comes were in the third and fourth quintiles

re-vealed findings similar to those from analyses that

also included children of less affluent families

hav-ing incomes in the second quintile. Although the

findings in the more restricted and smaller sample

did not reach statistical significance for some

mea-sures, the trend remained similar to that found in

the larger middle class sample. For example, black

children still were more likely to lack the same

source of care for routine and sick care (10.1% vs

6.5%;

P

5

.06), more likely to use emergency

de-partments as their source of sick care (4.2% vs

2.2%;

P

5

.07); and less likely to receive mental

health (4.4% vs 5.9%;

P

5

.22) or special education

services (2.8% vs 4.1%;

P

5

.13). Among children

who experienced educational difficulties, black

TABLE 1. Demographic and Family Characteristics of Black and White Middle Class Children and Youth with Private Health Insurance in the United States, Child Health Supplement to the 1988 National Health Interview Survey (N58381)

Black % (n5979)

White % (n57402)

P

Family income

Second quintile 39.3 26.3 ,.001

Third quintile 36.3 44.3 ,.001

Fourth quintile 13.8 20.5 ,.001

Middle class, quintile unknown* 10.5 8.9 NS Region

Northeast 15.4 20.2 ,.05

Midwest 18.0 30.6 ,.001

South 58.5 30.4 ,.001

West 8.1 18.8 ,.001

Degree of urbanization

Urban 34.4 10.4 ,.001

Suburban 16.8 25.5 ,.001

Other 48.9 64.1 ,.01

Maternal education

,High school 13.1 11.6 .28

High school 47.9 48.3 .87

.High school 39.0 40.1 .61

Household composition

Single parent 31.3 12.4 ,.001

Two parents 68.7 87.6 ,.001

Maternal age at child’s birth

#16 y 3.6 1.4 ,.01

.16 y 96.4 98.6 ,.01

* Family reported that income was$$20 000, but failed to give exact amount.

TABLE 2. Physical Health and Behavior and School Problems of Black and White Middle Class Children and Youth with Private Health Insurance in the United States, Child Health Supplement to the 1988 National Health Interview Survey (N58381)

Black % (n5979) White % (n57402) P

Physical health Health status

Excellent 46.2 57.3 ,.001

Very good or good 51.3 41.0 ,.001

Fair or poor 2.5 1.7 .30

Low birth weight (,2500 g) 10.7 5.6 ,.001

Very low birth weight (,1500 g) 1.4 0.6 .08

Ever had frequent ear infections 16.9 27.9 ,.001

Ever had asthma 8.5 5.8 .01

Chronic health conditions

None 80.8 71.5 ,.001

1 16.1 21.9 .001

2 2.0 4.8 ,.001

.2 1.0 1.8 .07

Chronic health condition and limitations of activity

Major activity limited 4.5 5.1 .45

School activity limited 5.1 6.1 .19

Days in bed in last 12 mo

0 63.3 44.1 ,.001

1–5 28.5 41.9 ,.001

6–10 5.7 8.6 .002

11–20 1.6 3.8 ,.001

.20 0.8 1.6 .02

Household member currently a smoker 41.9 39.2 .29

Household members smoked since child born 49.7 49.8 .95

Psychological and school functioning

Behavior Problem Index score$90 percentile 7.5 8.3 .51

Felt to need psychological help in the past 12 mo 1.8 1.7 .88

Repeated any grade 20.0 12.3 ,.001

children in these quintiles also were less likely to

receive both special education (9.6% vs 19.4%;

P

,

.05) and mental health (6.4% vs 14.5%;

P

,

.06)

services.

Multivariate Analyses

Table 5 demonstrates adjusted ORs for selected

measures of health, behavior and school problems,

and sources of care and use of services, controlling

for family income and size, source of routine care,

region, urbanization, gender, single- vs two-parent

household, and maternal age at child’s birth. Black

children in these quintiles still were less likely to

be reported as being in excellent health (OR: 0.7,

95% CI: 0.6 – 0.8), and they still were more likely to

have been born with a low birth weight (OR: 1.9,

95% CI: 1.3–2.8) and to have asthma (OR: 1.4, 95%

CI: 1.01–2.0;

P

,

.05). Black children also remained

at increased risk for having ever been suspended

from school (OR: 2.2, 95% CI: 1.5–3.3) and tended

to have higher rates of repeating a grade (OR: 1.4,

95% CI: 0.98 –1.9;

P

5

.07) in adjusted analyses.

In multivariate analyses, race no longer was

as-sociated with disparities in lack of a usual source of

sick care, but black children still were more likely

to lack continuity of routine and sick care. The

likelihood of black children overall ever having

received mental health or special education

ser-vices, although still less than that of white

chil-dren, was now of marginal statistical significance.

Similarly, among children who had ever repeated a

grade or had ever been suspended from school,

although no longer statistically significant, the

trend was still for black children to be less likely to

have received special education services or to have

seen a psychiatrist or counselor. Black children

still were found to use physicians’ offices for

rou-tine care half as often (OR: 0.4, 95% CI: 0.3– 0.5)

and emergency departments for sick care three

times as often as white children (OR: 3.2, 95% CI:

1.7–5.8). Not shown are data from a linear

regres-sion model indicating that black children still had

fewer physician visits than did white children (

P

,

.001).

DISCUSSION

This study differs from other studies of

chil-dren’s health and use of health services in that it

focuses on middle class black and white children

who have private health insurance. Black and

white children were found to have comparable

rates of being up to date with well-child care. In

contrast, they differed substantially on many

mea-sures of utilization of services, and most of these

differences persisted in multivariate analyses and

analyses restricted to more economically privileged

middle class children, as well as across the entire

middle class income range. Black children were

TABLE 3. Comparison of Sources of Care and Use of Medical, Mental Health, and Special Education Services by Black and White Middle Class Children and Youth with Private Insurance in the United States, Child Health Supplement to the 1988 National Health Interview Survey (N58381)

Black % (n5979)

White % (n57402)

P

Lack usual sources of care

Routine care 7.8 6.2 .22

Sick care 6.6 3.8 ,.01

Same source of care for routine and sick care 13.8 7.5 ,.001

Usual place for routine care

Physician’s office 79.4 92.8 ,.001

Outpatient’s clinic 13.1 4.5 .001

Health center 7.2 2.4 ,.001

Usual place for sick care

Physician’s office 81.8 92.0 ,.001

Outpatient clinic 8.9 4.1 ,.001

Health center 3.9 1.6 ,.05

Emergency department 5.4 2.4 ,.01

Number of physician visits in last 12 mo

0 29.5 17.8 ,.001

1–5 62.7 67.6 ,.05

6–10 5.7 10.3 ,.001

11–20 1.8 3.0 .01

.2 0.4 1.2 .001

Not current with well-child care 20.7 21.8 .54

,2 y 9.0 8.8 .94

2–5 y 21.6 23.7 .56

6–12 y 20.5 24.0 .23

13–17 y 23.8 22.3 .71

No. of short-stay hospital episodes in last 12 mo

0 97.5 96.7 .20

1–5 2.5 3.2 .23

.5 0.0 0.04 .11

Ever seen psychiatrist or counselor 3.6 5.8 ,.05

Received special education services for developmental delay, learning disability, or emotional/behavioral problem

3.0 4.2 .09

Repeated any grade or was ever suspended from school, and:

Received special education services 11.8 18.8 ,.05

more likely to lack a usual source for sick care and

continuity of routine and sick care, get their care

from outpatient clinics and health centers, and use

emergency rooms, and they made fewer physician

visits.

Privately insured middle class black children

were more likely to have been born with low birth

weight, a finding consistent with other studies

showing this same difference among infants born to

nonpoor parents.

39,40They also were more likely to

have asthma, a finding compatible with results of

other studies

32,41– 43that show that higher rates of

this condition among black children cannot be

ex-plained entirely by social or economic factors. In

contrast, black children were reported as having

fewer chronic health conditions overall and similar

TABLE 4. Physical Health, Behavior and School Problems, Sources of Care, and Use of Medical, Mental Health, and Special Education Services by Black and White Children with Private Health Insurance and Family Incomes in the Third and Fourth Quintiles Child Health Supplement to the 1988 National Health Interview Survey (N55263)

Black % (n5502)

White % (n54761)

Urban residence 34.9 10.6*

Single-parent household 22.8 9.5*

Maternal age at child’s birth#16 y 1.6 1.2

Physical health

Health status excellent 50.2 59.8*

No chronic conditions 78.9 71.2*

Low birth weight 11.6 5.2*

Ever had asthma 9.5 5.9*

Psychological and school functioning

Behavior Problem Index Score$90 percentile 7.6 7.9

Repeated any grade 17.5 11.3*

Ever suspended from school 11.5 5.0*

Medical and related service use Lack usual source of

Routine care 5.3 5.2

Sick care 6.4 3.2*

Same source routine and sick care 10.1 6.5**

Usual place for routine care:

Physician’s office 83.2 94.2*

Outpatient clinic 12.1 3.8*

Health center 4.5 1.8*

Usual place for sick is emergency department 4.2 2.2***

Not current with well-child care 17.7 21.5*

Ever seen psychiatrist or counselor 4.4 5.9

Received special education services for developmental delay, learning disability, or emotional/behavioral problem

2.8 4.1

Repeated any grade or was ever suspended from school and

Received special education services 9.6 19.4*

Ever seen psychiatrist or counselor 6.4 14.5**

*P,.05; **P5.06; ***P5.07.

TABLE 5. Adjusted ORs* for Selected Measures of Health, Behavior and School Problems, Sources of Care, and Health Services Utilization by Privately Insured, Middle Class Black Children and Youth in the United States,** Child Health Supplement to the 1988 National Health Interview Survey (N58381)

OR 95% CI P

Excellent health 0.7 0.6–0.8 ,.001

Ever had asthma 1.4 1.01–2.0 ,.05

Low birth weight 1.9 1.3–2.8 ,.001

Repeated any grade 1.4 0.96–1.9 .09

Ever suspended from school 2.2 1.5–3.3 ,.001

Lack

Usual source of sick care 1.3 0.8–2.2 .34

Same source of care for routine and sick care 1.9 1.2–2.9 .01

Physician’s office is usual place for routine care 0.4 0.3–0.5 ,.001

Emergency department is usual place for sick care 3.0 1.7–5.5 ,.001

Ever seen psychiatrist or counselor 0.5 0.2–1.1 .10

Psychiatrist or counselor felt needed, but never seen 0.7 0.3–1.9 .50

Ever seen psychiatrist or counselor, child has BPI$90th percentile*** 2.0 0.5–7.9 .30

Ever received special education services 0.6 0.4–1.1 .09

Repeated any grade or ever suspended from school

Received special education services 0.6 0.3–1.2 .12

Ever seen psychiatrist or counselor 0.5 0.2–1.8 .31

* Independent Variables tested include second (lower), third (middle), and fourth (upper) middle class income quintiles; age; source of routine care (outpatient clinic, health center, emergency department, physician’s office); region (Midwest, South, West, Northeast); urbanization (large or small city, suburban, rural); gender; household composition (single- or two-parent); maternal age at child’s birth (#16 y or.16 y); and family size.

rates of limitations of activity because of these

con-ditions, yet they were less likely to be perceived by

their parents as being in excellent health. Although

black children and white children had similar rates

of behavior problems, black children were twice as

likely to have repeated a grade or to have been

suspended from school. In multivariate analyses,

the association of children’s race and repeating a

grade was no longer statistically significant (OR:

1.4;

P

5

.09), but black children were still more

than twice as likely to have been suspended from

school compared with their white peers. We are

unaware of any previous studies indicating this

heightened risk for black middle class children.

Other studies, although not focusing on middle

class children, also have found increased rates of

discontinuity of routine and sick care, increased

use of hospital outpatient departments and

com-munity health centers,

1,2,18,44and decreased

num-bers of ambulatory care visits by black

chil-dren.

13,45,46Although it appears that the increased

rates of lacking continuity of care were attributable

to their increased use of community health centers

and hospital outpatient departments, this does not

appear to account for black children’s diminished

use of private physicians for routine care, their

increased reliance on emergency departments for

sick care, or their fewer ambulatory care visits,

because these differences persisted in multivariate

analyses that controlled for their source of routine

care. The data available provide no insights into

whether these differences are attributable to

nonfi-nancial barriers to care,

46,47such as long waits and

diminished evening and weekend availability at

hospital outpatient departments and community

health centers; longer distance to or more difficult

access to private physicians’ offices; families

feel-ing out of place in some practice settfeel-ings; or overt

or covert discrimination.

There are other limitations to these data. All data

were from parent report, with limited information

available about many important aspects of

chil-dren’s insurance and health care. Potentially

im-portant unassessed factors include the

comprehen-siveness, cost-sharing (ie, copays or deductibles),

and limits of insurance coverage; content,

compre-hensiveness, and cultural appropriateness of care

received; variability of any of these characteristics

with degree of urbanization, specific city, state, or

region of the United States; and factors influencing

choice of sources of care. There also was no

infor-mation available regarding family wealth (ie,

finan-cial assets), and resources such as home ownership,

cars, other material possessions and liquid savings

might influence the patterns of service use noted.

Also, the data are 10 years old, predating the rapid

introduction of managed care into many

communi-ties.

Despite the limitations, these data offer what we

believe is the first detailed picture of the health,

behavior and school problems, and use of medical,

mental health, and special education services of

black and white middle class children in the

United States. They demonstrate similar rates of

health and behavior problems, but substantially

in-creased rates of school difficulties among black

children. They also demonstrate no differences in

rates of having a usual source of routine care being

current with well-child care, or receiving mental

health or special education services. In contrast,

even in the presence of private health insurance,

middle class black children had markedly different

sources and patterns of ambulatory medical service

use. Although the findings do not identify the

mechanisms behind the differences, they clearly

demonstrate the increased risk and relative

disad-vantage that black race appears to portend for

mid-dle class children in the United States. These and

similar findings, we believe, are crucial to our

ef-forts to ensure equal access to medical services for

all our children, irrespective of their income,

insur-ance, or race.

REFERENCES

1. Blendon RJ, Aiken LH, Freeman HE, Corey CR. Access to medical care for black and white Americans.JAMA.1989;261:278 –281 2. Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. Black–white disparities in

health care.JAMA.1990;263:2344 –2346

3. Strogatz D. Use of medical care for chest pain: differences between blacks and whites.Am J Public Health.1990;80:290 –294

4. Navarro V. Race or class versus race and class: mortality differentials in the United States.Lancet.1990;336:1238 –1240

5. Council on Scientific Affairs of the American Medical Association. Hispanic health in the United States.JAMA.1991;265:248 –252 6. Public Health Service. Healthy People 2000: National Health

Promo-tion and Disease PrevenPromo-tion Objectives. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. DHHS publica-tion no. (PHS)91-50212; 1991

7. Lieu TA, Newacheck PW, McManus MA. Race, ethnicity, and access to ambulatory care among US adolescents.Am J Public Health.1993; 83:960 –965

8. Gornick ME, Eggers PW, Reilly TW, et al. Effects of race and income on mortality and use of services among Medicare Beneficiaries.

N Engl J Med.1996;335:791–799

9. Geiger HJ. Race and health care—an American dilemma?N Engl J Med.1996;335:815– 816

10. Peterson ED, Shaw BS, DeLong ER, Pryor DB, Califf RM, Mark DB. Racial variation in the use of coronary revascularization procedures.

N Engl J Med.1997;336:480 – 486

11. Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, Folkman S, Syme SL. Socioeco-nomic inequalities in health: no easy solution. JAMA. 1993;269: 3140 –3145

12. Pappas G. Elucidating the relationships between race, socioeconomic status, and health.Am J Public Health.1994;84:892– 893

13. Kleinman JC, Gold M, Makuc D. Use of ambulatory care by the poor: another look at equity.Med Care.1981;19:1011–1029

14. Egbuonu BS, Starfield B. Child health and social status.Pediatrics.

1982;69:550 –557

15. Starfield B. Family income, ill health, and medical care of US chil-dren.J Public Health Policy.1982;3:244 –259

16. Newacheck PW, Halfon N. Preventive care use by school-aged chil-dren. Differences by socioeconomic status. Pediatrics. 1988;82: 462– 468

17. Wise PH, Meyers A. Poverty and child health.Pediatr Clin North Am.

1988;35:1169 –1186

18. St. Peter RF, Newacheck PW, Halfon N. Access to care for poor children: separate and unequal?JAMA.1992;267:2760 –2764 19. Holl JL, Szilagyi PG, Rodewald LE, Byrd RS, Weitzman M. Profile of

uninsured children in the United States.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.

1995;149:398 – 406

20. Sheils JF, Wolfe PR. The role of private health insurance in children’s health care.Future Child.1992;2:115–133

21. Adams PF, Hardy AM. Current estimates from the National Health Interview Survey: United States, 1988.Vital Health Stat.1989;173: 1–11, 133–144

Health Statistics. Advance data fromVital Health Stat.No. 188; 1990 23. US Bureau of the Census.Middle Class and Income Inequality. Cur-rent Population Reports, Series P60. Washington, DC: US Bureau of the Census; 1997. http://www.census.gov/hhes/income/midclass/ midclsan.html

24. Massey JT.Design and Estimation for the National Health Interview Survey, 1985–94. Data Evaluation and Methods Research. Vital Health Stat–Series 2;1989;110:1–33

25. Collins JG, Hendershot GE.Health Characteristics of Large Metro-politan Statistical Areas: United States, 1988 – 89. Vital Health Stat–Series 10; 1993;187:1–97. Data from the National Health Sur-vey. US Bureau of the Census. Statistical Abstracts of the United States: 1993 (113th ed). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1993

26. Newacheck PW, Stoddard JJ, McManus P. Ethnocultural variations in the prevalence and impact of childhood chronic conditions. Pediat-rics.1993;91:1031–1039

27. Weitzman M, Byrd RS, Auinger P. Children in big cities in the United States: health and related needs and services.Ambulatory Child Health.1996;1:347–359

28. Peterson JL, Zill N. Marital disruption, parent– child relationships, and behavior problems in children.J Marriage Fam.1986;48:295–307 29. Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C.Manual for the Child Behavior Check-list and Revised Child Behavior Profile.Burlington, VT: Queen City Printers; 1983

30. Gortmaker SL, Walker DK, Weitzman M, Sobol AM. Chronic condi-tions, socioeconomic risks, and behavioral problems in children and adolescents.Pediatrics.1990;85:267–276

31. Byrd RS, Weitzman M. Predictors of early grade retention among children in the United States.Pediatrics.1994;93:481– 487 32. Weitzman M, Gortmaker SL, Sobol AM, Perrin JM. Recent trends in

the prevalence and severity of childhood asthma.JAMA.1992;268: 2673–2677

33. McCormick MC, Gortmaker SL, Sobol AM. Very low birthweight children: behavior problems and school difficulty in a national sam-ple.J Pediatr.1990;117:687– 693

34. Weitzman M, Gortmaker SL, Sobol AM. Maternal smoking and

be-havior problems of children.Pediatrics.1992;90:342–349

35. Byrd RS, Weitzman M, Auinger P. Behavior problems, age-for-grade and grade retention among children in the United States.Pediatrics.

In press

36. American Academy of Pediatrics.Guidelines for Health Supervision II. Elk Grove Village, IL American Academy of Pediatrics; 1988 37. SAS Institute Inc.SAS/STAT User’s Guide: Statistics. Release 6.03

ed. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1988

38. Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Hunt N, LaVange LM.SUDAAN User’s Man-ualRelease 6.40. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 1995

39. Barfield WD, Wise PH, Rust FP, Rust KJ, Gould JB, Gortmaker SL. Racial disparities in outcomes of military and civilian births in Cal-ifornia.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.1996;150:1062–1067

40. Schoendorf KC, Hogue CJR, Kleinman JC, Rowley D. Mortality among infants of black as compared with white college-educated parents.

N Engl J Med.1992;326:1522–1526

41. Weitzman M, Gortmaker S, Sobol A. Racial, social, and environmen-tal risks for childhood asthma.Am J Dis Child.1990;144:1189 –1194 42. Cunningham J, Dockery DW, Speizer FE. Race, asthma, and persistent wheeze in Philadelphia school children.Am J Public Health.1996; 86:1406 –1409

43. Gergen P. Social class and asthma— distinguishing between the dis-ease and the diagnosis.Am J Public Health.1996;86:1361–1362 44. Hahn BA. Children’s health. Racial and ethnic differences in the use

of prescription medications.Pediatrics.1995;95:727–732

45. Wood DL, Hayward RA, Corey CR, Freeman HE, Shapiro MF. Access to medical care for children and adolescents in the United States.

Pediatrics.1990;86:666 – 673

46. Orr ST, Miller CA, James SA. Differences in use of health services by children according to race: relative importance of cultural and sys-tem-related factors.Med Care.1984;22:848 – 853