After The 2004 Act On Punishment Of Intermediating In The Sex Trade

THE POLICE CRACKDOWN IN RED

LIGHT DISTRICTS IN SOUTH KOREA

AND THE CRIME DISPLACEMENT

EFFECT AFTER THE 2004 ACT ON THE

PUNISHMENT OF INTERMEDIATING

IN THE SEX TRADE

Kyungseok Choo*, Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology,

University Of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, Massachusetts, USA

Kyung-Shick Choi, Department of Criminal Justice, Bridgewater State

University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts, USA; and Yong-Eun Sung,

School of Criminal Justice, Rutgers University, Newark, New Jersey, USA

Abstract

In September of 2004, the government of South Korea enacted the ‘Act on the Punishment of Intermediating in the Sex Trade’. Included in the law are strict penalties such as large fines and long prison sentences for both the owners of brothels and their patrons. The enactment was initiated after shocking news of the deaths in a series of fire events of 24 sex workers confined in brothels within red light districts. The first tragedy was in Gunsan city in September 2000. Five sex workers who were confined in a sex establishment were unable to escape a fire and were killed. Five months later, four sex workers were killed in a fire in Busan city and, in January 2002, 14 sex workers, including two owners, were killed in Gunsan city. Subsequent investigations found that many sex workers were trafficked into the sex industry and treated as commodities by sex business owners. For example, some workers were sold in debt bondage to brothel owners. Numerous social activists and NGOs have raised concerns about existing policies and laws prohibiting prostitution, the cruel and inhuman conditions and practices of the sex business industry, and the human rights of sex workers (Presidential Commission on Policy Planning, 2008).

Immediately following the enactment of the Act on the Punishment of Intermediating in the Sex Trade, intensive police crackdowns were implemented on the owners of brothels and their patrons. A year later, the number of brothels and sex workers had reduced dramatically. According to the Criminal White Paper of the National Police Agency in South Korea, the number of brothels in red light districts decreased 37.5% from 1,698 in September 2004 to 1,061 in September 2005. In addition, the number of sex workers decreased 18.4% from 3,142 to 2,653 in the same period.

Despite aggressive police crackdowns, which resulted in a visible reduction of brothels and sex workers, many observers in Korea have suggested that the sex trade in South Korea has been displaced from red light districts to more clandestine locations, including barbershops, karaoke parlours, massage parlours, and even cyberspace (Ann, 2007; Choi, 2007; Heo, 2008; Kang, 2005; Lee, 2009; Park, 2006). They argue that the act does little more than suppress the sex trade in one place, which then causes it to resurface somewhere else. Crime displacement occurs when a criminal activity is relocated from one place, time, target, offence, or tactic to another, as result of some crime control initiative. Choi (2007), for example, observed that, unlike traditional brothels in red light districts, which were clustered together, the new forms of sex trade establishments that emerged after the act was implemented were scattered in a residential area and located among other small businesses, including dry cleaners and hardware stores. According to Choi, new patrons cannot find these new sex establishments because they are not distinguished by signs, and most of them operate in closed buildings with an underground entrance that is barred by an iron door. This new form of the sex trade business can be understood as spatial and tactical crime displacement from a red light district to a residential area and from traditional brothels to clandestine venues.

After The 2004 Act On Punishment Of Intermediating In The Sex Trade Whatever its specific type, displacement is an adaptive response and is a central concern of

researchers, policymakers, and others concerned with crime control/prevention and proactive policing. An examination of the impact of the new anti-prostitution law in South Korea will provide the potential for a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of displacement, if any, as well as important implications for policy. The paper first introduces the theoretical background of crime displacement. It provides compelling theories and general concepts of crime displacement. A discussion then follows, of an official crime data on prostitution in the years 2000 to 2009 and a news content analysis of crime displacement based on 174 newspaper articles, as well as a secondary data analysis derived from a survey of 1,078 Korean sex workers in seven cities throughout South Korea. Finally, the paper discusses the implications for both theory and policy in order to improve our understanding of the current anti-prostitution policy and efforts to control prostitution.

Crime displacement

Crime displacement can be examined from a number of angles, which would include temporal, spatial, target, tactical, and offence (see e.g. Reppetto, 1976; Hakim and Rengert, 1981; Guerette, 2009). These forms of crime displacement are elaborated as:

• Temporal: offenders change the time at which they commit crime

• Spatial: offenders switch from targets in one location to targets in another location • Target: offenders change from one type of target to another

• Tactical: offenders alter the methods used to carry out crime • Offence: offenders switch from one form of crime to another.

No matter what the type of displacement, the result is the same - the crime is not ultimately prevented or controlled, but simply altered in form or moved to a new location. An additional and more worrisome form of displacement is the possible escalation of the seriousness of crime in response to a preventive approach or a control measure, such as the enactment and enforcement of a law in targeting a particular crime problem. It can be argued that displacement eliminates any benefits that crime prevention or control initiatives bring, and may even make the situation worse.

The most important issue for displacement is the inevitability of crime displacement. The argument for the inevitability of crime displacement can be traced back to traditional ‘hydraulic’ theories of criminal behaviour, according to which offenders are seen as being almost compelled to commit crimes (Gabor, 1981). Based on this argument, the offenders (e.g., the sex workers and brothel owners in our study) must seek alternative ways of

that prompted them. Since much criminal activity can be attributed to this type of offender, eliminating opportunities should result in a dramatic decrease in overall crime (McNamara, 1994). Following this assumption, Felson and Clarke (1998) argued that opportunity does affect the motivation of opportunistic offenders. They included professional and chronic offenders while arguing that the reduction of opportunity does not displace crime. Furthermore, Cornish and Clarke (1987) argued that if there is any displacement, it occurs only under particular circumstances, assuming that offenders respond selectively to their opportunities by considering the cost and benefits of crime - the choice structuring properties of crime - in deciding whether or not to displace their activities elsewhere.

Both conflicting theoretical perspectives and inconsistent empirical evidence concerning the displacement of crime after prevention and control measures have resulted in different views on displacement. For instance, studies on suicide (Clarke and Mayhew, 1988), motorcycle theft (Mayhew, Clarke, and Elliott, 1989), cheque forgery (Knutsson and Kuhlhorn, 1981), and obscene phone calls (Clarke, 1990), all illustrated that crime displacement is minimal or can be avoided. The evidence provided by these empirical research projects has lent support to the belief that crime displacement is not inevitable, and that it can be prevented or controlled through the implementation of appropriate crime policies. Other compelling studies, however, showed empirical evidence suggesting that the threat of crime displacement occurs in burglary (Allatt, 1984; Gabor, 1981), street drug markets (Curtis and Sviridoff, 1994) and robbery (Chaiken, Lawless, and Stevenson, 1974).

After The 2004 Act On Punishment Of Intermediating In The Sex Trade prostitutes and ‘drift in and out’ girls simply desisted from the prostitution to which they

were only marginally committed, which led the Finsbury Park study to conclude that there was little displacement effect. However, Matthews (1993) reported that spatial and temporal displacement occurred in another area because the commitment to prostitution was much stronger than that of the ‘away-day’ and ‘drift in and out’ girls in Finsbury Park.

When displacement is a result of the implementation of control measures, a somewhat more sophisticated argument concerns the magnitude of the displacement. Barr and Pease (1990) introduced the concepts of ‘benign’ and ‘malign’ displacement. Benign displacement occurs if the crime is displaced from a ‘hot spot’ to another area (equal distribution of victimisation) and from more serious forms to less serious forms. This line of study provides evidence for the existence of displacement, although it is unknown whether the amount of displacement is less than or equal to the removed quantities of crime. Even if total benign displacement emerges after successful control measures, the effect of benign displacement is considered to be a partially successful crime control effort. Nevertheless, a scholarly debate continues regarding malign displacement, which refers to displaced crimes that are similar in seriousness to or more serious than those controlled. Some studies again implied the possibility of malign displacement (Chaiken et al., 1974; Ekblom, 1987), and many showed concern around whether crime control measures substantially escalate the level and seriousness of crime.

In this study, we discuss the possibility of malign displacement in the sex industry of South Korea after the 2004 act was implemented. In the following sections, we examine official crime statistics on the illegal sex trade and provide a media content analysis about spatial and tactical crime displacement from red light districts to more clandestine locations such as barbershops, room salons, karaoke, and massage parlours.

The effect of the Act on the Punishment of

Intermediating in the Sex Trade in South Korea

Figure 1 Number of brothels and prostitutes in South Korea, 2001–2009

*Source: Korean National Police Agency, Annual Report of Criminal White Paper, 2002-2010.

Figure 1 shows the number of brothels and prostitutes from 2001 to 2009 reported in the Criminal White Paper of the Korean National Police Agency. A total of 1,736 brothels and 5,846 prostitutes were reported in 2001, respectively. These figures remained relatively stable in 2002 and 2003. The number of prostitutes then dropped 46% from 5,793 in 2003 to 3,142 in 2004 when the Act on the Punishment of Intermediating in the Sex Trade was passed. The number of brothels also significantly dropped 38% from 1,698 in 2004 to 1,061 in 2005. Then, both the number of prostitutes and brothels remains at a low level until 2009, respectively. It is important to note that the immediate impact of the 2004 act resulted in a sudden decrease in the number of prostitutes, while the decline in the number of brothels occurred one year after the act was implemented. This lag effect provides a valuable insight into how prostitutes and brothel owners, respectively, responded to the police crackdown after the 2004 act was in place.

Figure 2 Number of prostitution cases reported in South Korea, 2000-2009

*Source: Supreme Prosecutor’s Office of the Republic of Korea, Annual Report of Crime Analysis (2001-2010).

*Note: All figures prior to the Act on the Punishment of Intermediating in the Sex Trade are the numbers of the violation of the Prostitution Prevention Act, which regulated prostitution in Korea before the new prostitution act of 2004.

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Number of Prostitutes 5,846 6,396 5,793 3,142 2,653 2,663 2,523 2,282 1,882 Number of Brothels 1,736 1,872 1,738 1,698 1,061 1,097 999 935 853

0 1,000 2,000 3,000 4,000 5,000 6,000 7,000 8,000 9,000

2,571 4,093 3,589 3,336 3,740 3,804

6,942 7,849

15,875 24,430

0 5,000 10,000 15,000 20,000 25,000 30,000

After The 2004 Act On Punishment Of Intermediating In The Sex Trade Figure 2 represents an aggregate data from the Annual Report of Crime Analysis from 2000

to 2009, compiled by the Supreme Prosecutor’s Office of the Republic of Korea. The annual reports include data not only on the total number of arrests but also on the number of crimes reported to law enforcement agencies. The number of reported prostitution cases is relatively stable from 2000 to 2005, until 2006 when the number starts to escalate significantly. Interestingly, when compared to the year 2000, the number of reported prostitution cases in 2009 was approximately ten times higher. The trend for the number of prostitution cases shown in figure 2 is virtually contrary to that of prostitutes and brothels in figure 1. This particular phenomenon may be explained by the enactment and enforcement of the Act on the Punishment of Intermediating in the Sex Trade. In other words, the rapid increase in reported prostitution cases during the post-2005 period is considered as a consequence of aggressive police crackdowns, driven by the new 2004 act.

When the reported prostitution cases are broken down into the actual number of arrestees by gender, not only is a different angle provided but also further evidence of a rapid change in the illegal sex trade market in South Korea is confirmed. Figure 3 shows the total number by gender of arrested offenders involved in prostitution from 2000 to 2009. The number of arrestees and the number of reported cases of prostitution have an identical pattern, which shows an increase since 2006. Almost all the male arrestees are clients, while the female arrestees are prostitutes, brothel or sex trade business owners, or managers. It should be noted that the male sex buyers were typically released with a caution during the period of the previous Prostitution Prevention Act. The new 2004 anti-prostitution act aggressively targets clients, pimps, and brothel owners while, from a human rights perspective, it treats prostitutes as victims of trafficking. Figure 3 clearly reflects the effects of the new 2004 act.

Figure 3 Number of the arrestees for prostitution by gender in South Korea, 2000-2009

*Source: Supreme Prosecutor’s Office of the Republic of Korea, Annual Report of Crime Analysis (2001-2010)

*Note: All figures prior to the Act on the Punishment of Intermediating in the Sex Trade are the numbers of the violation of the Prostitution Prevention Act, which regulated prostitution in Korea before the new prostitution act of 2004.

The increase in the number of female arrestees, combined with the significant increase in the overall number of prostitution cases during the post-2005 period shown in Figure 2, also implies that prostitutes were likely to be displaced to other forms of the sex trade business, instead of simply desisting from prostitution. Overall, the total number of arrestees increased about 10 times from 2000 to 2009. The data in Figures 2 and 3 shows that the sex trade in South Korea has even escalated despite the immediate impact of the 2004 act, which helped reduce the number of brothels and prostitutes in red light districts, as shown in Figure 1. Overall, the rapid increase in prostitution cases and arrested offenders during the post-2005 period indirectly implies that the anti-prostitution act was ineffective as a control measure. A news content analysis from 2004 to 2009 even suggests a possibility of displacement from red light districts to more clandestine locations after the new 2004 act.

Numerous news media articles were released on the effectiveness of the new anti-prostitution act. A total of 3,734 news articles regarding the 2004 act were released between September 2004 and September 2009 (see Jang, Choo and Choi, 2009 for news content analysis in detail). To determine the presence of crime displacement in media content, we used two key phrases: ‘effectiveness of the 2004 act’ and ‘balloon effect of the 2004 act’. The news articles were narrowed down to 408, of which 174 related to covert forms of sex trade business, i.e., tactical displacement. Figure 4 shows these news articles broken down by year. The number increased significantly in 2005 (n=34) from the previous year, 2004 (n=12). Thereafter, the number remained steady both in 2006 (n=30) and 2007 (n=28). In 2008 (n=38), the number increased again, although it dropped in 2009 (n=32). The news articles clearly indicated that many furtive forms of illicit sexual businesses right after aggressive police crackdown strategies on traditional sex trade businesses such as brothels in red light districts. In addition, the police and the prosecutors have encountered major impediments because secretive forms of prostitution have hindered investigation and prosecution due to the absence of the application of a law.

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Total Numebr of Arrested

Offenders 6,419 10,884 10,049 9,868 10,770 14,090 26,772 31,314 46,062 65,626 Male 2,978 4,766 4,712 4,519 6,120 10,415 22,007 25,220 38,330 53,999 Female 3,441 6,118 5,337 5,349 4,650 3,675 4,765 6,094 7,762 11,627

After The 2004 Act On Punishment Of Intermediating In The Sex Trade

Figure 4 Tactical displacement, 2004-2009

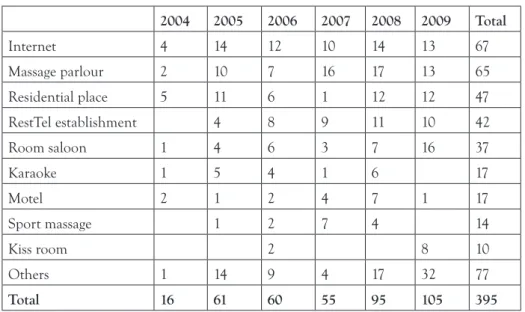

Within tactical displacement, we identified 32 different forms of sex trade and 395 counts of tactical displacements from 2004 to 2009. The numbers exceed the total number of news articles because more than one tactical displacement can be coded in a news article. Most of the news articles indicated more than one tactical displacement. Table 1 illustrates the first ten, most frequently cited, forms of sex trade since the 2004 act. It should be noted that the Internet (n=67, 17%) was the most frequently identified form of a new sex trade. (This is considered to be an individual sex trade arrangement.)

This is followed by the massage parlour business establishment (n=65, 16.4%), the residential place (n=47, 11.9%), a RestTel establishment (n=42, 10.6%), and room saloon (n=37, 9.4%). Although massage parlour establishments and room saloons were used as sex trade places before the 2004 act, sex trade arrangements through the internet, in residential places and RestTel establishments are considered to be new trends of the sex trade, emerging since the 2004 act. In addition, some articles indicated rare and unusual cases of new sex trade such as at a Sushi Bar, Golf Saloon, Doll Room, or Thematic Sex Trade establishment. Although many of these cases were counted only once, they were all found in news articles in 2009. From this, we assume that new forms of the sex trade are constantly evolving since the 2004 act. The breakdown of tactical displacements by year also shows the pattern of new forms in the sex trade evolving from 2004 to 2009. There were a few articles of tactical displacement in 2004 (n=16). The number more than tripled in 2005 (n=61), and kept more or less steady in 2006 (n=60) and 2007 (n=55). Interestingly, the number increases sharply in 2008 (n=95) and again in 2009 (n=105).

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 12

34

30

28

38

Table 1 Types of tactical displacement, 2004-2009

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Total

Internet 4 14 12 10 14 13 67

Massage parlour 2 10 7 16 17 13 65

Residential place 5 11 6 1 12 12 47

RestTel establishment 4 8 9 11 10 42

Room saloon 1 4 6 3 7 16 37

Karaoke 1 5 4 1 6 17

Motel 2 1 2 4 7 1 17

Sport massage 1 2 7 4 14

Kiss room 2 8 10

Others 1 14 9 4 17 32 77

Total 16 61 60 55 95 105 395

The data used are proxies for the actual behaviour of prostitutes. Nevertheless, from the results of the official law enforcement data and news content analysis, it is reasonable to assume that new and more clandestine forms of illegal sex trade business will continue to emerge and sex workers will displace into them. We now turn to our attention to the voices of sex workers in brothels in South Korea. We are particularly interested in any relationship between previous prostitution experience of the brothel sex workers and their willingness to move to other illegal sex trade businesses after the implementation of the 2004 act, which will be analysed using a secondary data set.

Voices of sex workers

Secondary data

The secondary data set was derived from a survey of 1,079 Korean sex workers in 11 major brothels in 7 cities throughout South Korea from February 3rd to 12th in 2006. The original data was collected for the purpose of cross-sectional assessment on the general circumstances of sex trade businesses after the implementation of the 2004 act. The original data set* completed a total of 999 participants (92.6%) out of 1,079 excluding 80 participants who responded to less than 50% of the questionnaire, and primarily focused on the assessment of 1) general characteristics among sex workers, 2) sex workers’ health conditions, 3) sexually transmitted diseases in the brothel areas, 4) current state of prostitution laws, and 5) new forms of prostitution.

After The 2004 Act On Punishment Of Intermediating In The Sex Trade Our focal interest is to measure displacement effects examining sex workers’ willingness to

engage in new forms of prostitution, as well as the likelihood of this event after implementing the 2004 act. For the purpose of this study, we identified 387 sex workers, who plan to work in different forms of sex trade within the 10 listed categories other than brothel prostitution, for the analysis. They are as follows: 1) Karaoke; 2) Massage Parlour; 3) Sex Barbershop; 4) Room Salon; 5) Out-call Massage; 6) Ticket Café; 7) Sex Inn; 8) RestTel; 9) Overseas Prostitution; and 10) Internet Prostitution.

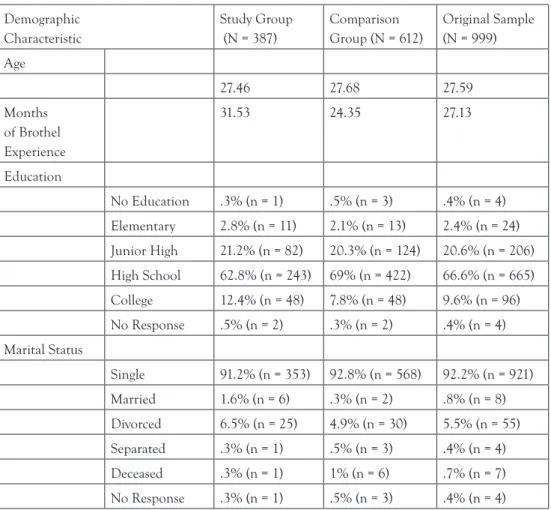

We compared general demographic characteristics of the 387 study samples and 612 sex workers who are not willing to work in different forms of sex trade in the future in terms of age, months of brothel experience, education, and marital status, as shown in Table 2. The mean age of both samples was almost identical (27.46 and 27.68 respectively). The mean months of brothel experience of the original sample was 27.13 months. Intriguingly, our study sample had about 6 additional months of experience in brothel life compared to that of the comparison group. Both samples indicated having a similar education background and marital status.

Table 2 Comparison of demographic characteristics between study and comparison group

Demographic Characteristic

Study Group (N = 387)

Comparison Group (N = 612)

Original Sample (N = 999) Age

27.46 27.68 27.59

Months of Brothel Experience

31.53 24.35 27.13

Education

No Education .3% (n = 1) .5% (n = 3) .4% (n = 4)

Elementary 2.8% (n = 11) 2.1% (n = 13) 2.4% (n = 24)

Junior High 21.2% (n = 82) 20.3% (n = 124) 20.6% (n = 206) High School 62.8% (n = 243) 69% (n = 422) 66.6% (n = 665)

College 12.4% (n = 48) 7.8% (n = 48) 9.6% (n = 96)

No Response .5% (n = 2) .3% (n = 2) .4% (n = 4)

Marital Status

Single 91.2% (n = 353) 92.8% (n = 568) 92.2% (n = 921)

Married 1.6% (n = 6) .3% (n = 2) .8% (n = 8)

A majority of the study group (n=243, 62.8%) and comparison group (n= 422, 69%) had a high school diploma, and the second most common level of education among samples was junior high school (n=82, 21.2% and n=124, 20.3% respectively). Interestingly, 12.4% of the study sample had a college degree while 7.8% of the comparison group indicated college degree completion. In terms of marital status, over 90% of both groups were single.

Hypotheses and variables

The study hypothesised that the number of exposures to other forms of prostitution prior to the 2004 act increases sex workers’ likelihood and motivation to engage in these forms of prostitution after the legal implementation.

Hypothesis 1:

Sex workers who previously experienced different types of prostitution forms other than brothel areas are likely to explore working in more diverse forms of prostitution after the legal implementation.

In order to estimate the number of exposures to other forms of prostitution, we examined each category of other forms of prostitution to test this hypothesis. The measure consisted of 10 items as indicated earlier, and each item was measured in the survey by asking the respondents to state what types of prostitution they experienced prior to the legal implementation. The respondents were also asked to state what types of prostitution they plan to engage in the future. The 10 items consisted of a dichotomous structure, which was identified with 0 as absence of engagement in the specific form of prostitution, and 1 as engagement in the specific form of prostitution. In other words, each scale was coded 1 for a Yes response and 0 for a No response to carry the statistical meaning. Thus, the dependent measure was reconstructed by summing the total scores via reflection of individual responses from each of categories in this study. The number of experiences within the 10 types of prostitution represents the level of exposure and likelihood of engagement in other forms of prostitution, based on before and after the legal implementation. Since respondents marked at least one of 10 types of prostitution, the scale’s possible aggregate range is 1 to 10, with higher scores reflecting higher exposure to other forms of prostitution.

Hypothesis 2:

A sex worker who worked in a specific form of prostitution before the legal implementation is likely to engage in the same type of prostitution after the legal implementation.

After The 2004 Act On Punishment Of Intermediating In The Sex Trade implementation. The dichotomous categories were originally assigned a code of 1 for a Yes

response and 0 for a No response, and the possible range for each of the independent and dependent measures was from 0 to 1.

Results of the analysis

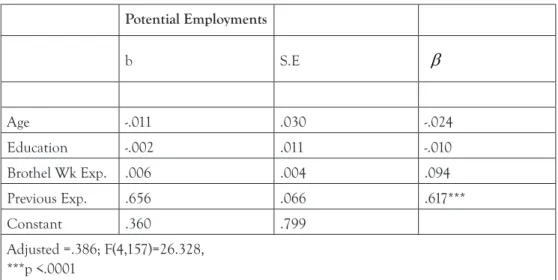

Multiple regression analysis was applied to examine whether the number of previous

experiences in other forms of prostitution has a substantial impact on the number of potential engagements in other forms of prostitution. We included variables such as age, education, and the duration of brothel experience in the analysis. Regression assumptions were previously checked and were not being violated.

Table 3 Summary of multiple regression analysis for age, education, brothel work experience, and previous experience predicting potential number of employments in different forms of prostitution (N = 162)

Potential Employments

b S.E

Age -.011 .030 -.024

Education -.002 .011 -.010

Brothel Wk Exp. .006 .004 .094

Previous Exp. .656 .066 .617***

Constant .360 .799

Adjusted =.386; F(4,157)=26.328, ***p <.0001

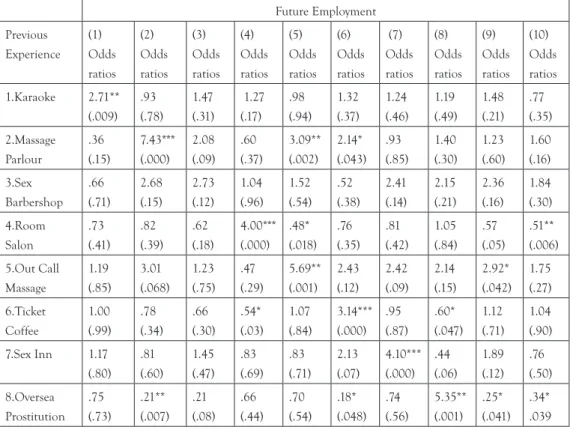

in the future. The Omnibus Tests of Model Coefficients table indicates that when we enter each of the predictors, each of the models is significant. In other words, when reflecting sex workers’ prostitution experiences, significant predictions are found in their potential future engagement in the same type of prostitution, coded as future employment. The ‘pseudo’ R2

(Nagelkerke R2) offers a rough estimate of the variance that can be predicted from each of the

previous work experiences, based on 10 types of prostitution.

The findings indicate that previous work experience in all types of prostitution was statistically significant, with the exception of previous experience in a sex barbershop. Interestingly, previous work experience in a massage parlour appears to be a very strong predictor when compared to each of other predictors. The odds ratio of 7.43 for massage parlour suggests that sex workers who had work experience in massage parlours are 7.4 times more likely to seek work in massage parlours as a future job. In addition, the odds ratio for out call massage was 5.69, which suggests that the odds of working in out call massage in the future improve by 5.69 for engagement in the same type of prostitution prior to the legal implementation. In addition, the odds of working in overseas prostitution, internet prostitution, and sex inns also increased substantially by 5.35, 4.94, and 4.10 respectively with previous experience.

Table 4 Logistic regression predicting future employments within 10 types of prostitution

Future Employment Previous Experience (1) Odds ratios (2) Odds ratios (3) Odds ratios (4) Odds ratios (5) Odds ratios (6) Odds ratios (7) Odds ratios (8) Odds ratios (9) Odds ratios (10) Odds ratios 1.Karaoke 2.71** (.009) .93 (.78) 1.47 (.31) 1.27 (.17) .98 (.94) 1.32 (.37) 1.24 (.46) 1.19 (.49) 1.48 (.21) .77 (.35) 2.Massage Parlour .36 (.15) 7.43*** (.000) 2.08 (.09) .60 (.37) 3.09** (.002) 2.14* (.043) .93 (.85) 1.40 (.30) 1.23 (.60) 1.60 (.16) 3.Sex Barbershop .66 (.71) 2.68 (.15) 2.73 (.12) 1.04 (.96) 1.52 (.54) .52 (.38) 2.41 (.14) 2.15 (.21) 2.36 (.16) 1.84 (.30) 4.Room Salon .73 (.41) .82 (.39) .62 (.18) 4.00*** (.000) .48* (.018) .76 (.35) .81 (.42) 1.05 (.84) .57 (.05) .51** (.006) 5.Out Call Massage 1.19 (.85) 3.01 (.068) 1.23 (.75) .47 (.29) 5.69** (.001) 2.43 (.12) 2.42 (.09) 2.14 (.15) 2.92* (.042) 1.75 (.27) 6.Ticket Coffee 1.00 (.99) .78 (.34) .66 (.30) .54* (.03) 1.07 (.84) 3.14*** (.000) .95 (.87) .60* (.047) 1.12 (.71) 1.04 (.90) 7.Sex Inn 1.17

After The 2004 Act On Punishment Of Intermediating In The Sex Trade

9.Rest-tel 1.29 (.78)

1.05 (.94)

2.55 (.14)

1.19 (.79)

2.14 (.19)

.48 (.26)

2.44 (.10)

1.27 (.67)

3.17* (.034)

1.77 (.29) 10.Internet

Prostitution .86 (.82)

1.12 (.79)

.51 (.34)

.25* (.02)

1.24 (.67)

1.48 (.41)

1.91 (.11)

2.24* (.047)

1.49 (.38)

4.94 (.000) N 387 387 387 387 387 387 387 387 387 387 -2 Log

likelihood

229.1 462.4 247.6 423.9 313.3 326.6 384.2 475.3 334.9 444.2

Nagelkerke R2 .06 .21 .11 .19 .24 .15 .16 .16 .16 .14

Figures in parentheses are p-values of Wald X2 statistics (with one degree of freedom),

computed as squares of the parameter estimates divided by their estimated standard errors. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

These results suggest the odds of working in the same type of prostitution in the future are increasingly greater when a sex worker has previously worked in the same type of prostitution. This is particularly noticeable in the areas of massage parlour, out call massage, overseas prostitution, and Internet prostitution. This implies previous work experience is a salient causal factor in displacement among the sex workers. Accordingly, effective enforcement for the mentioned sex trade forms would be crucial to minimise the overall displacement effects.

Theory and policy implication

Based on the findings drawn from our analysis of the official crime data, the news content, and the secondary data regarding crime displacement, we attempt in this section to provide a theoretical explanation of crime displacement. We assume that crime displacement is shaped and determined primarily by three factors: implementation of preventive or control measures (i.e., the act promoting punishment of the sex trade and law enforcement such as police crackdowns); characteristics of the target population (i.e., sex workers, pimps, brothel owners, clients); criminal opportunity structure (i.e., familiarity with the structure of sex trade business and accessibility to similar forms of sex trade businesses in other areas).

it should be understood that the 2004 act is considered to be intensive and permanent from the offenders’ perspective. Massive law enforcement practices of this law have forced them to make alternative plans and search for new opportunities, including clandestine forms of the sex trade business in residential areas and on the internet.

The characteristics of the target population will influence the nature of crime displacement. We assume that active sex workers, pimps, and owners will react immediately to a police crackdown or other control measures, compared with individuals primarily involved in other forms of sex trade businesses in non-targeted areas. For example, when the 2004 act was passed and implemented, thousands of active owners and sex workers demonstrated against a police crackdown, claiming that it was a violation of human rights and job equality. We assume that many of these protesters have subsequently desisted from the sex trade business. Nevertheless, if our findings from official data, news content, and secondary data analysis correctly support the tactical and spatial displacement phenomenon, then core and chronic offenders continue to work in non-targeted areas or in other forms of the sex trade business. In addition, it is expected that the ‘Johns’ (clients) who ‘demand the stability ‘of the illegal sex trade business will also influence sex trade displacement, as shown in Figure 3.

There is a time lag while offenders search for, and gain familiarity with, alternative criminal opportunities. This time lag will affect the process of crime displacement. Offenders in the sex trade business will seek out similarly structured forms of illegal sex trade to commit when their favoured method is blocked. They will move to non-targeted areas, or to other forms of sex trade business. However, their search for alternative criminal opportunities will be determined by factors such as the availability of information, the ability of the offenders, and acquaintance with their new target. In a drug market analysis of crime displacement, Curits and Svirdoff (1994) argued that it was not the actions of law enforcement per se that determined whether displacement takes place or not, but rather, the social organisation of street-level drug markets. Therefore, crime displacement in the sex trade business also depends on favourable social structures within other forms of sex trade in the non-targeted area. For the same reason, the time lag also refers to the period of adjustment required by ‘displaced offenders’ to become familiar with their new conditions. In other words, if offenders in the sex trade business are less familiar with their alternative criminal opportunities, their displacement will occur more slowly. If offenders become comfortable quickly with the new opportunities in other forms of sex trade business, the probability of crime displacement increases and speeds up. As these concepts indicate, offenders need time to adjust themselves to alternative forms of offence once their preferred path is blocked.

Conclusion

After The 2004 Act On Punishment Of Intermediating In The Sex Trade and Pease, 1990; Weisburd and Green, 1995) and researchers’ priorities on the main effects

(Eck, 1993).

Weiss (1995) stressed the importance of a theory-driven approach, arguing that it helps to avoid many of the pitfalls that threaten evaluation research after preventive/control measures are implemented. According to Weiss, a theory-driven approach appears to serve focusing on key aspects of the initiatives, generating knowledge about key theories of change, making explicit assumptions, defining methods, clarifying goals, and influencing policy. Our findings, driven by multiple data sources, are a guide for detailed and clear ‘propositions’ of crime displacement theory. Despite the complexity of the varying levels of displacement, we postulate that the likelihood and process of crime displacement is determined and shaped primarily by three main factors—opportunity structure, characteristics of the target population, and control/preventive measures.

An obvious question asks whether the propositions here can be tested and validated. The answer concerns methodology, which in turn requires us to develop or identify appropriate measurements of the displacement process. Regarding measurement issues, a unique evaluation design should be developed and followed. If our propositions are valid, then careful analysis of the possible impact, including the displacement effect of a control measure, must precede its implementation. In addition, the pre-implementation analysis should examine the characteristics of the target population, the opportunity structure, and the scope of the control measures. By acknowledging the need for follow up research and further theory development, our study has important implications for evaluation of the impact of new anti-prostitution laws and law enforcement strategies, especially with regard to the possibility of crime displacement.

References

Allatt, P. 1984. ‘Residential Security: Containment and Displacement of Burglary’. Howard Journal of Criminal Justice 23 (2): 99-116

Ann, H.J. 2007 (September, 10). ‘Changed Cultural Landscape after 3 Years of the Enactment of the Act on the Punishment of Intermediating in the Sex Trade’. Kukmin Newspaper

Barr, R. and Pease, K. 1990. ‘Crime Placement, Displacement and Deflection’. In M. Tonry and N. Morris (eds.), Crime and Justice: A review of Research, Vol. 12. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press

Chaiken, J., Lawless, M. and Stevenson, K. 1974. The Impact of Police Activity on Crime: Robberies on the New York City Subway System. Report No. R-1424-N.Y.C. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation

Choi, H.Y. 2007 (December). ‘Shocking! Infiltration Reportage: High School Prostitute Village in the Middle of Metropolitan Seoul’. Shindonga Magazine 579:168-177

Clarke, R.V. 1990. ‘Deterring Obscene Phone Callers: Preliminary Results of the New Jersey Experience’. Security Journal 1: 143-148

Clarke, R.V. and Mayhew, P 1988. ‘The British Gas Suicide Story and Its Criminological Implications’. In M. Tonry and N. Morris (eds.), Crime and Justice: A review of Research, Vol. 10. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press

Felson M. and Clarke. R.V. 1998. Opportunity Makes the Thief: Practical Theory for Crime Prevention. Crime Prevention Unit Paper 98. London: Home Office

Gabor, T. 1981. ‘The Crime Displacement Hypothesis: An empirical Examination’. Crime and Delinquency 26:390-404

Guerette, R.T. 2009. Analyzing Crime Displacement and Diffusion. Washington, D.C., USA: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, United States Department of Justice.

Hakim, S. and Rengert, G. 1981. ‘Introduction’. In S. Hakim and G.F. Rengert (eds.), Crime Spillover. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage

Haney, C., Banks, W. C., and Zimbardo, P. G. 1973. ‘Interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison’. International Journal of Criminology and Penology 1: 69–97.

Heo, J.H. 2008 (September 23). ‘Interview with Sex Workers: After 4 years of the Enactment of the Act on the Punishment of Intermediating in the Sex Trade’. Korea Times

Holt, T.J., Blevins, K.R., and Kuhns, J.B. 2008. ‘Examining the displacement practices of johns with on-line data’. Journal of Criminal Justice 36: 522-528

Hubbard, P. 1998. ‘Community Action and the Displacement of Street Prostitution: Evidence from British Cities’. Geoforum 29 (3): 269-286

Jang, J.O., Choo, K., and Choi, K.S. 2009. Human Trafficking and Smuggling of Korean Women for Sexual Exploitation to the United States. Seoul, South Korea: Korean Institute of Criminology

Kang, S.H. 2005. (March, 20). ‘One Year after the Act on the Punishment of Intermediating in the Sex Trade: New Pattern of Sex Trade Using the Internet’. Yonhap News

Kelling, G.L. and J.W. Wilson. 1982 (March). ‘Broken Windows’. The Atlantic Monthly

Knutsson, J. and Kuhlhorn, E. 1981. Macro-measures Against Crime. The Example of Check Forgeries. Information Bulletin No. 1. Stockholm, Sweden: National Swedish Council for Crime Prevention.

McNamara, R.P. 1994. ‘Hustlers in a Shifting Marketplace: The Effects of Displacement on Male Prostitution’. American Journal of Police 13(3): 95-117

Matthews, R. 1990. ‘Developing More Effective Strategies for Curbing Prostitution’. Security Journal 1:182-187 Matthews, R. 1993. Kerb-Crawling, Prostitution and Multi-Agency Policing. London. UK: Home Office Police

Department

Mayhew, P., Clarke, R.V. and Elliott, D. 1989. ‘Motorcycle Theft, Helmet Legislation and Displacement’. Howard Journal of Criminal Justice 28: 1-8

Murphy, A. K., and Venkatesh, S. A. 2006. ‘Vice careers: The changing contours of sex work in New York City’. Qualitative Sociology, 29, 129 154.

Lee, K.J. 2009. ‘Evaluation and Recommendation after 4 Years of the Enactment of the Act on Punishment of Intermediating Sex Trade’. Korean Criminological Review 20 (1): 701-720

Lowman, J. 1992. ‘Street Prostitution Control; Some Canadian Reflections on the Finsbury Park Experience’. British Journal of Criminology 32:1-17.

Park, S.W. 2006. (September, 25). ‘More than a Half is Married Men in Sex Trade’ Daily No-cut News

Presidential Commission on Policy Planning. 2008. Prevention of Sex Trade: toward Improvement of Women’s Right through Eradication of Sex Trade. Policy Report 2-29. Seoul: South Korea

Reppetto, T.A. 1976. ‘Crime Prevention and the displacement phenomenon’. Crime and Delinquency 22:166-177 Weisburd, D. and Green, L. 1995. ‘Policing Drug Hot Sports: The Jersey City Drug Market Analysis Experiment’.

Justice Quarterly 12(4): 711-734