Int J Geriatr Psychiatry2003;18: 839–843.

Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com).DOI: 10.1002/gps.994

Locations of facilities with special programs for older

substance abuse clients in the US

Susan K. Schultz

1, Stephan Arndt

1,2,3* and Jill Liesveld

1 1Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA

2Department of Biostatistics, College of Public Health, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA

3Iowa Consortium for Substance Abuse Research and Evaluation, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA

SUMMARY

Background Given the growth of our aging population, developing strategies for managing late-life alcoholism is increas-ingly important.

Objective We compared substance abuse treatment facilities with and without services designed for older adults and explored the location of these services relative to the regional distribution of older adults across the United States. Methods A public use dataset from a national survey of facilities offering substance abuse treatment was used to address this issue. This survey included all identified substance abuse/dependence treatment facilities in the US and surveyed the facilities’ treatment services, services for special groups, number of clients admitted, type of ownership (e.g. public, private for profit), and whether or not the facility was associated with a hospital, as well as questions about licensure and income sources.

Results Of the 13 749 responding facilities, relatively few programs (17.7%) were specifically designed for older adults (i.e. over age 65). Facilities with such programs tended to be associated with hospitals, particularly those with a psychiatric inpatient service. Importantly, the number of facilities with special programs for older adults did not correlate with size of the older population in each state.

Conclusion Despite an increasing need for older adult substance abuse services, there are relatively few programs avail-able designed for this age group. The setting where patients with substance abuse are identified (e.g. in a hospital) may partially explain the pattern of locations of age-specific programs. Copyright#2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

key words— alcoholism; substance abuse; substance abuse treatment

INTRODUCTION

There is a relatively low rate of substance abuse in the older population, often estimated at 10–15% or less (Peterson and Zimberg, 1996). However, the implica-tions for increased medical morbidity with advanced age make this a particularly serious public health pro-blem. For example, a review of medical records from 1988 and 1997 indicated a 46% increase in

alcohol-related hospitalizations among older pa-tients (Whitmoreet al., 1999). Another recent report (SAMHSA, 2002a) indicated a 58% increase in emer-gency room visits with a notation of alcohol and other drug involvement for patients over age 55. A similar study exploring 32 382 trauma visits for persons over age 65 showed that only 5% were tested for the pre-sence of alcohol, but within this group 50% tested positive for significant blood alcohol levels (Zautcke, 2002). This study also demonstrated that falls and motor vehicle accidents were the most common sources of trauma among those who were positive for alcohol, attesting to the severe implications of alcohol abuse in late life.

The study by Zautcke (2002) highlights the impor-tance of increased identification of alcoholism in late

Received 3 February 2003

* Correspondence to: S. Arndt, Director, Iowa Consortium for Substance Abuse Research, 100 Oakdale Campus M317 OH, Iowa City, IA 52242-5000, USA. Tel: +1 319 335-4921.

Fax: +1 319 353-3003. E-mail: stephan-arndt@uiowa.edu Contract/grant Sponsor: State of Iowa to the Iowa Consortium for Substance Abuse Research and Evaluation, University of Iowa.

life. However, once the problem is identified in a given patient, agencies and clinicians then face a need to initiate necessary treatment referrals. There is some evidence that older individuals with substance abuse problems may respond more favorably to treatment programs designed for their age group (Blow et al., 2000). Indeed some centers have modeled commu-nity-based substance abuse programs designed speci-fically for the elderly that involve home visits and multi-dimensional treatment planning (Brymer and Rusnell, 2000). This study reported a significant reduction in drugs of abuse, including narcotic, ben-zodiazepines and other prescription medications. While not all programs may be this intensive, at a minimum older subjects may benefit from programs geared for their age-specific issues and challenges. Furthermore, given that older clients are often less mobile and may have transportation problems if grams are not local, it is also important that these pro-grams are distributed in a way that is accessible to the population of interest. In sum, the clinician may find it difficult to find suitable treatment facilities for older adults that are also accessible.

Given these barriers, clinicians may opt to postpone referrals to see if the problem remits without treat-ment. However, a three-year longitudinal study which followed older adults with alcohol problems found that few problems resolved over time (Waltonet al., 2000). For older persons with substance abuse disor-ders, the alcohol problems remained stable and did not mitigate over the period. This suggests that it may be in the best interest of the patient to initiate referrals promptly after recognition of the problem.

Given the significant incidence of hospitalizations and emergency visits associated with alcoholism, locating treatment facilities for older clients is an important concern. We addressed this issue using a national survey of substance abuse facilities that inquired whether programs for older clients were available. We then characterized whether the facilities did or did not offer services for older adults, and then compared them in terms of various clinical features. The locations of these facilities were also explored relative to the regional distributions of older adults across the United States.

METHODS

The dataset utilized was comprised of data from the National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Ser-vices (National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services or N-SSATS; 2000, 2002). Surveys were mailed to all known facilities in the United States,

public and private, that provide substance abuse treat-ment. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Ser-vices Administration (SAMHSA), Office of Applied Studies conducted the N-SSATS survey (SAMHSA, 2002b). Following the letters of introduction by the state’s licensing authority, surveys were mailed to facility directors. Follow-up mailings and telephone calls were made to the facility directors to increase the response rates.

Of 17 374 facilities contacted for the survey, 15.7% were not eligible since they had closed, did not pro-vide substance abuse treatment, or served incarcer-ated clients only. Of those eligible facilities, 94% (13 749) responded.

The survey included information about services, number of clients admitted, type of ownership (e.g. public, private for profit), whether or not the facility was associated with a hospital and questions about licensure and income sources.

For the statistical analysis,2-tests, Mann–Whitney U-tests, and Spearman correlations were used. A logis-tic regression analysis was also performed predicting whether the facility provided special services for older adults. To control for an inflated type I error from mul-tiple tests, we set the significance threshold at 0.01 and for the simple analysis of two by two cross-tabulation tables, we regarded a 5% difference as the minimal meaningful difference. Our outcome variable was the facility’s response to the question ‘Does this facility offer substance abuse treatment specifically designed for seniors/older adults?’ Twelve respondents did not respond, such that the resultingn¼13 416.

RESULTS

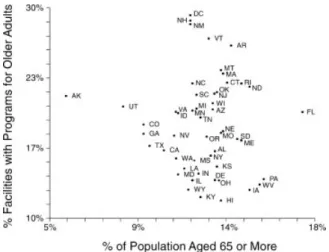

Only 17.7% (2374) facilities reported providing ser-vices designed specifically for older adults, although states varied widely. The percentage of facilities offering an older adult program against the percentage of the population aged 65 or older based on 2001 US Census data (Census Bureau Population Estimates as of 1 July 2001, 2002) are presented in Figure 1. Hawaii (11.7%), Kentucky (12%), and Iowa (12.7%) had few such programs given the relatively high percentages of people over age 65 in these states. In contrast, the District of Columbia (29.3%), New Hampshire (28.8%), and New Mexico (28.4%) had large proportions of facilities with programs for older substance abusers. There was no appreciable correla-tion across the US between the states’ populacorrela-tion proportion aged 65 and older and the proportion of treatment facilities with services for these clients (Spearman’sr¼ 0.20,n¼51,p>0.15).

Facilities that had more admissions were slight-ly more likeslight-ly to have programs for older adults (Mann–Whitney test, z¼3.64, n¼12 046, p<

0.0003). For facilities offering programs for older adults, the median number of admissions was 162 (mean¼362.6, SD¼649.1) compared to a median of 139 (322.9, SD¼980.7) for facilities that did not offer programs. The type of administrative manage-ment was also associated with whether a program for older adults was offered (2¼87.68, df¼5, p<0.0001). Private for profit (21.9%), tribal govern-ment (29%) and federal governgovern-ment (21.6%) facilities were more likely to offer such programs while private not-for-profit (15.7) and state government (13.3%) facilities were least likely. Among federal facilities, those run by the Department of Veteran Affairs (28.3%) and the Indian Health Service (27.5%) pro-vide specialized services most often.

Substance abuse treatment facilities owned by or operated in a hospital most commonly offered pro-grams for older adults (24.6%vs 16.4%;2¼80.99, df¼1,p<0.0001). Among facilities associated with hospitals, 23.1% of those within a general hospital and 31.9% of those within a psychiatric hospital offered services for older clients. Facilities that offered both hospital inpatient detoxification and rehabilita-tion were more likely (37.6%) to provide services for older clients than facilities that only offered inpa-tient detoxification (35.9%) or inpainpa-tient rehabilitation (25.9%,2¼19.57, df¼2,p<0.0001).

The facility’s clinical focus was also associated with offering a special program for older clients (2¼93.02, df¼4, p<0.0001). Facilities focused

on general health care (22.6%) or a mix of mental health and substance abuse (22.6%) often provided the specialized service. Facilities that focused primar-ily on substance abuse treatment were the least likely (15.4%) to offer special services for older adults.

Facilities that supported programs for older adults differed from facilities that did not in terms of the types of payment received. The full model based on a logistic regression using all questioned sources indi-cated a significant overall effect (likelihood

2¼262.69, df¼7,p<0.0001). A backwards elimi-nation procedure left four reimbursement sources associated with special programs for older adults. Facilities that accepted Medicare payments were 1.825 [Confidence Intervals (CI)¼1.6–2.1] times more likely to provide such services (Wald

2¼85.53, df¼1, p<0.0001). Accepting federal military insurance was also marginally associated with delivering such programs [odds ratio (OR)¼

1.26, CI¼1.2–1.4, Wald 2¼15.24, df¼1, p<

0.0001]. Facilities accepting Medicaid (OR¼ 0.79, CI¼0.7–0.9) or other sources of federal, state, and local funds for substance abuse treatment (OR¼

0.65, CI¼0.6–0.7) offered fewer programs for older adults. These associations persisted after controlling for the facilities’ hospital association status.

Facilities that were not part of a network of sub-stance abuse treatment sites tended to provide special programs (22.5%) more often than facilities asso-ciated with a network (14.9%; 2¼122.60, df¼1, p<0.0001). Although only 2.6% of the facilities reported accreditation from the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), those that were accredited were more apt to provide these services (30%) than those that were not accredited (16.9%,

2¼35.90, df¼1,p<0.0001).

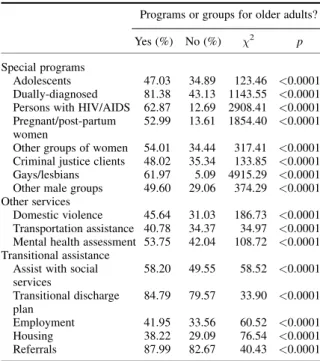

Table 1 compares facilities with and without pro-grams for older adults on their provision of other spe-cial services are compared in Table 1. Facilities that offered groups or programs for older adults also pro-vided more specialized programs for other groups of clients. For instance, facilities with programs for older adults, more often provided programs for dually diagnosed clients, gay and lesbian groups, pregnant or post-partum women, and adolescents.

DISCUSSION

Despite an increasing need for older adult services for alcohol treatment, there are relatively few programs for this age group; less than one in five existing pro-grams offer services specifically designed for older adults. Moreover, the presence of such programs does Figure 1. Percent of each state’s population who were aged 65 or

more and the percent of substance abuse treatment facilities offering special programs for older adults

not correlate with the size of the older population within each state. Even when age-appropriate services do exist, a referral may pose a number of problems for the older client who may have transportation difficul-ties or other special needs. The findings from this study point to a number of interesting relationships and elucidate some of the barriers encountered by the older patient that may affect the success of the treatment referral for substance abuse services.

An interesting finding was that facilities that pro-vided programs for older clients were frequently asso-ciated with hospitals. There may be several reasons for this. Older clients most often have a problem with alcohol as opposed to other substances of abuse (Fingerhood, 2000). Older alcohol users also experi-ence greater medical complications during alcohol withdrawal such as delirium tremens and hypokale-mia and require a greater length of hospital stay (Ing-ster and Cartwright, 1995; Wojnaret al., 2001). Thus, older clients need more medical care due to condi-tions associated with age and due to the potential complications from withdrawal. Furthermore, the abuse problem in an older patient is frequently detected when withdrawal symptoms occur during hospitalizations for other conditions and procedures. Hence referrals may be made directly from the hospi-tal setting to the substance abuse treatment unit.

Within one hospital based substance abuse consul-tation service, the most common reason for an older

(aged 60 or older) patient to enter the hospital and trigger the referral was trauma (e.g. from falls), fol-lowed by cardiac and gastro-intestinal difficulties (Weintraubet al., 2002). In another study of hospital admissions that was associated with a substance abuse diagnosis, 71% of the patients were initially admitted for medical or surgical reasons and the remaining 29% were admitted to psychiatry (Mulinga, 1999). It is possible that the higher rate of special programs for older adults in hospitals results from the fact that the older adults’ alcohol problems come to light within the hospital setting. As other agencies become involved in identification of substance abuse among older clients, alternative methods of interventions may become more widespread (Blow and Barry, 2000) and programs for older adults may become more common in community facilities and alternative providers.

There are also issues about the perceived need for specialized services for older substance abusing clients. Increased medical complications may make the treatment of older clients somewhat different from the general adult population. There is also evi-dence that older clients seem to do well in elder specific treatment programs (Blowet al., 2000). How-ever, there is little direct evidence that older clients do better with the specifically designed treatment, since older clients also do well in standard programs (Fitzgerald and Mulford, 1992; Lemke and Moos, 2002). Standards of care for treatment include sensi-tivity to the client’s special needs and, when imple-mented properly, may be sufficient for addressing the needs of the older adult. As awareness of sub-stance abuse treatment issues surrounding the older adult increases, we expect to see clinical trials con-trasting specifically designed programs to standard care.

There are several limitations to the present study. The N-SSATS database attempts to be inclusive of treatment facilities throughout the United States. However, it is likely that the survey does not include every treatment facility. Facilities funded through public sources (e.g. state funded facilities) may be more easily identified than facilities such as small pri-vate hospitals. Also, the N-SSATS questions are necessarily limited in scope. There are many ques-tions about special programs for older clients that might be interesting, e.g. the size, intensity, and spe-cific attributes of the program. Thus, the results pre-sented here can only address broad questions regarding accessibility of such programs. A more detailed survey on a smaller sample of these programs would yield much richer information.

Table 1. Characteristics of programs with older client services Programs or groups for older adults? Yes (%) No (%) 2 p

Special programs

Adolescents 47.03 34.89 123.46 <0.0001 Dually-diagnosed 81.38 43.13 1143.55 <0.0001 Persons with HIV/AIDS 62.87 12.69 2908.41 <0.0001 Pregnant/post-partum 52.99 13.61 1854.40 <0.0001 women

Other groups of women 54.01 34.44 317.41 <0.0001 Criminal justice clients 48.02 35.34 133.85 <0.0001 Gays/lesbians 61.97 5.09 4915.29 <0.0001 Other male groups 49.60 29.06 374.29 <0.0001 Other services

Domestic violence 45.64 31.03 186.73 <0.0001 Transportation assistance 40.78 34.37 34.97 <0.0001 Mental health assessment 53.75 42.04 108.72 <0.0001 Transitional assistance

Assist with social 58.20 49.55 58.52 <0.0001 services Transitional discharge 84.79 79.57 33.90 <0.0001 plan Employment 41.95 33.56 60.52 <0.0001 Housing 38.22 29.09 76.54 <0.0001 Referrals 87.99 82.67 40.43 <0.0001

The need for specialized programs for older clients is an important issue to address in the near future. Potential solutions may involve creating more specia-lized programs for older adults or modifying current programs to better accommodate the older clients’ special needs. As the US population ages, particularly in rural states with rapidly growing populations of older individuals, accessibility of treatment for older clients will become a critical issue.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This project was funded, in part, by an appropriation from the state of Iowa to the Iowa Consortium for Substance Abuse Research and Evaluation, Univer-sity of Iowa.

REFERENCES

Blow FC, Barry KL. 2000. Older patients with at-risk and problem drinking patterns: new developments in brief interventions.J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol13(3): 115–123.

Blow FC, Walton MA, Chermack ST, Mudd SA, Brower KJ. 2000. Older adult treatment outcome following elder-specific inpatient alcoholism treatment.J Subst Abuse Treat19: 67–75. Brymer C, Rusnell I. 2000. Reducing substance dependence in

elderly people: the side effects program.Can J Clin Pharmacol 7: 161–166.

Fingerhood M. 2000. Substance abuse in older people.J Am Geriatr Soc48(8): 985–995.

Fitzgerald JL, Mulford HA. 1992. Elderly vs. younger problem drinker ‘treatment’ and recovery experiences. Br J Addict 87(9): 1281–1291.

Ingster LM, Cartwright WS. 1995. Drug disorders and cardiovascu-lar disease: the impact on annual hospital length of stay for the medicare population.Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse21(1): 93–110.

Lemke S, Moos RH. 2002. Prognosis of older patients in mixed-age alcoholism treatment programs.J Subst Abuse Treat22: 33–43. Mulinga JD. 1999. Elderly people with alcohol-related problems:

where do they go?Int J Geriatr Psychiatry14(7): 564–566. Peterson M, Zimberg S. 1996. Treating alcoholism: an age-specific

intervention that works for older patients.Geriatrics 51(10): 45–49.

SAMHSA. 2002a.Emergency Department Trends from the Drug Abuse Warning Network, Final Estimates 1994–2001. DAWN Series D-21.DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 02-3635. DHHS: Rockville, MD.

SAMHSA. 2002b.National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS) 2000 [Computer file]. SAMHSA (ICPSR Ver-sion). Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research: Washington, DC.

Schucket MA, Tipp JE, Reich T, Hesselbrock VM, Bucholz KK. 1995. The histories of withdrawal convulsions and delirium tremens in 1648 alcohol dependent subjects. Addiction 90: 1335–1347.

US Administration on Aging. 2002. Census Bureau Population Estimates as of July 1, 2001 [http://www.aoa.dhhs.gov/aoa/ stats/2001pop/Pop-070102.html]. Washington, DC.

Walton MA, Mudd SA, Blow FC, Chermack ST, Gomberg ES. 2000. Stability in the drinking habits of older problem-drinkers recruited from nontreatment settings.J Subst Abuse Treat18(2): 169–177.

Weintraub E, Weintraub D, Dixon L,et al.2002. Geriatric patients on a substance abuse consultation service.Am J Geriatr Psychia-try10(3): 337–342.

Whitmore CC, Stinson FS, Dufour M. 1999.Surveillance Report #50, Trends in Alcohol-Related Morbidity Among Short-Stay Community Hospital Discharges in the United States 1979–97.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: Rockville, MD.

Wojnar M, Wasilewski D, Zmigrodzka I, Grobel I. 2001. Age-related differences in the course of alcohol withdrawal in hospi-talized patients.Alcohol Alcohol36: 577–583.

Zautcke JL, Coker SB, Morris RW, Stein-Spencer L. 2002. Geria-tric trauma in the State of Illinois: substance use and injury pat-ters.Am J Emerg Med20: 14–17.