Effectiveness of Integrated care programmes in adults with

chronic conditions: a systematic review

Authors

N. Martinez M.Sc.

PD Dr. P. Berchtold

Prof. Dr. A. Busato

Prof. Dr. M. Egger

Institution

Institute for Social and Preventive Medicine (ISPM), University of Bern, Finkenhubelweg 11,

CH-3012 Bern

Contact address for correspondence

PD Dr. P. Berchtold college-M Freiburgstrasse 41 CH-3010 Bern peter.berchtold@college-m.ch +41 31 632 30 70

CONTENT SUMMARY ... 3 INTRODUCTION ... 5 METHODS ... 7 RESULTS ... 10 DISCUSSION ... 19 LIMITATIONS ... 20 CONCLUSIONS ... 20 REFERENCES ... 21

SUMMARY Objectives

Stronger integration among health care providers is seen as an effective measure to improve quality of care while constraining cost growth in the setting of ageing populations and increasingly limited resources. In Switzerland, a growing part of primary care is provided by networks of physicians acting on the principles of gatekeeping and several initiatives targeting to improve care of chronic diseases have been developed by these networks as well as at regional and/or cantonal levels. The objectives of this study were to synthetize the evidence from published systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the effectiveness of integrated care programs on adult patients with chronic conditions.

Methods

Following the PRISMA guidelines for the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, a search strategy using broad definitions of comprehensive care with focus on vertical integration was developed and a literature search in major databases was performed. Reviews of studies of adult patients with chronic conditions published up to the end of March 2012 except AIDS, addiction, mental disorders and the field of midwifery were included.

Results

4008 citations were initially retrieved and 118 potentially relevant publications were identified. After assessing the full text we included 27 reviews reported in 28 publications for the final evaluation. Only eighteen of the 27 reviews reported the countries where primary studies were conducted: 49% in the USA, 34% in Europe and 17% in Canada, Australia and other countries.

A variety of concepts and components of integrated care have been reported in the reviews. Disease management was the most frequently used term to describe the concept of integrated care, other terms included case management, shared care, managed care, comprehensive care, multidisciplinary care, organised and coordinated care and chronic care model. Since these general terms represent a wide range of different integrated care concepts, we appraised these concepts further using a set of ten key elements of successful care integration. “Comprehensive services across the care continuum”, “patient focus” and “standardized care delivery through inter-professional teams” were the most frequent elements found. However, in almost half of the reviews only a small number of these elements could be identified suggesting that many initiatives to integrate health services follow a too selective approach and have a too narrow focus.

Various chronic conditions were investigated across the reviews. Chronic heart failure was the most commonly investigated condition (12/27) followed by diabetes and COPD each in seven reviews, asthma in four reviews. Cancer and rheumatoid arthritis were investigated in only two of the reviews. Information on the settings where the primary studies were conducted was available from 23 reviews and included a wide variety from inpatients to outpatients, ambulatory, discharge, nursing homes, rehabilitation centres etc..

All reviews examined complex concepts with multiple outcomes. Despite this heterogeneity, we report positive effects of integrated care concepts on patient satisfaction in diabetes and CHF patients, on functional capacity in CHF patients as well as better guideline adherence of providers and disease management for patients with diabetes. In contrast, inconclusive or no effects were

found regarding quality of life in patients with CHF, diabetes, COPD and asthma as well as mortality of patients with CHF or COPD.

Conclusions

Our systematic review provides evidence mainly from RCTs (506/603) showing variable effectiveness of care programmes for patients with chronic conditions. However the wide variety of concepts and programmes of integrated care evaluated in the literature limit the comparability between studies. Moreover, our review demonstrates that many initiatives and programmes of integrated care follow a too selective approach. Failure to include important dimensions for integrating health services such as "organizational culture and leadership" and "governance structure" may reduce the effectiveness of such programmes. Organisations that successfully integrate their health services align with and support all key dimensions of integration.

INTRODUCTION

Stronger integration and dedicated collaboration are viewed by many stakeholders within healthcare as an effective and sustainable package of measures suitable for improving the high quality and economy of healthcare in the future (Leape 2009). The reasoning behind is the realisation, that healthcare systems are basically fragmented or simply "non-integrated" because of the contradictory logic espoused by the individual players (Glouberman 2001). The consequences of this non-integration are well known: patient-care processes of low coherency, duplicate treatment tracks, treatment errors, etc. However, the true importance of integration will become evident in the future in light of the increase in prevalence of chronic and multimorbid disease conditions due to aging populations and increasing complexity of medical treatment (Strandberg-Larsen 2009).

Programmes for improving quality and effectiveness of patient care usually focus on single concepts and individual measures or comprise only parts of the whole process of patient care (Grol 2000). However, there is a growing interest for integration within and between the outpatient and inpatient sectors as well as for more collaboration between health professionals and medical disciplines (Ouwens 2005). In Switzerland, a growing part of primary care is provided by networks of physicians acting on the principles of gatekeeping. To date, an average of one out of six insured persons in Switzerland, and one out of three in the regions in north-eastern Switzerland, opted for the provision of care by general practitioners in one of the seventy six currently active physician networks. About 50% of all general practitioners have joined a physician network. Moreover, several initiatives targeting to improve care of chronic diseases have been developed by these networks as well as at regional and/or cantonal levels, such as clinical pathways for heart failure and breast cancer patients or chronic disease management programmes for patients with diabetes (Berchtold 2011).

Despite these developments, there is still only sparse information about the impact of health service delivery integration on feasibility and effectiveness and efficiency of care and on implications for potential health care reforms. A recent review of systematic reviews investigating effectiveness, definitions and components of integrated care programmes for chronic patients concluded that these programmes have positive effects on the quality of care. However, the conclusions were hampered by the fact that the studies were characterized by varying definitions of integrated care and components of care were described inaccurately (Ouwens 2005).

We aimed to synthesise the evidence of the effectiveness of integrated care programmes in the care of adult patients with chronic conditions from published systematic reviews and meta-analyses. We also assessed the interventions of the integrated care programmes evaluated in the included systematic reviews and meta-analyses. This review was conducted on request by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) within a legislative process of introducing a new bill for integrated care in Switzerland.

Definition of integrated care

Since integrated Care is a polymorphous concept viewed and understood very differently between national health systems as well as between the various actors within the health systems, there is no commonly accepted definition. In general, integrated care may be described as a “coherent set of

methods and models on the funding, administrative, organisational, service delivery and clinical levels designed to create connectivity, alignment and collaboration within and between the cure and care sectors” in order to overcome well-known shortcomings in health care such as the fragmentation of cure and care (processes), the concerns for equal access or the inefficiencies of and within health systems (Kodner 2009). Besides this rather abstract definition, many different terms are used in research projects and publications, such as disease management, case management, care coordination or multidisciplinary patient care.

In view of the increasing importance of physician networks in Switzerland, it is important to differentiate between two major orientations of care integration: (1) horizontal integration, where similar professionals or organisational units at the same level of care (e.g. within primary care) join together and (2) vertical integration which means collaboration over several levels with upstream and downstream care providers along the patient process of care (e.g. collaboration between primary care networks, hospitals and nursing homes). Ten years ago, almost all Swiss physician networks limited their membership to general practitioners, whereas today, more than two thirds of the networks also include specialised physicians and/or have contractual relationships with preceding (e.g. call center) and/or following service organisations (e.g. hospitals). It is obvious that vertical integration is the major driver for more comprehensive health service (Kodner 2009). In a previous review on the effectiveness of integrated care programmes, Ouwens et al. have stressed the fact that integrated care programmes use widely varying definitions and that failure to recognize these variations may lead to inappropriate conclusions and to inappropriate applications of the results (Ouwens 2005). A recent systematic review summarizing the current research literature on health system integration has identified ten universal key elements for successful integration (Suter 2009):

1) Comprehensive services across the care continuum 2) Patient focus

3) Geographic coverage and access

4) Standardized care delivery through inter-professional teams

5) Performance management

6) Information systems

7) Organisational culture and leadership 8) Physician integration

9) Governance structure 10)Financial management

These elements define the key dimensions for integrating care delivery (appendix). It has been suggested that concepts to integrate care delivery which embrace multiple of these dimensions are more capable of improving service quality and patient satisfaction. Although these key elements were intended to be used for strategic planning or restructuring initiatives, we suggest that these

METHODS

We followed the PRISMA guidelines for the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses and a protocol was developed a priori.

Reviews inclusion and exclusion criteria

We sought all systematic reviews and meta-analyses published in any language, from all years and from any country that examined the effects of integrated care in adult patients with chronic conditions except AIDS, addiction, mental disorders and the field of midwifery .

We focused on integrated care programmes that included at least two different institutional areas or services at different stages or levels of the patient care process, which were involved in the process of decision making and for which delivery of interventions was conducted under a multidisciplinary concept. We also included: studies reporting on transition of services and those in which adult patients with chronic conditions received integrated care for end-of-life; all components, all concepts and all comparisons regardless of whether any combination was reported; and we investigated all outcomes except costs. We excluded reviews with a focus on intensive care units, health technology assessments and clinical guidelines, non-systematic reviews and overviews. Finally, we excluded reviews from which data on the populations of interest –if more than one reported- could not be analysed separately, i.e. with distinction from each other.

At least two authors carried out independent inclusion and exclusion process resolving disagreements by discussion and when necessary unresolved differences were referred to a third author and consensus was reached. Inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in the appendix. Study identification and search strategy

In addressing the objective of this review, we performed a literature search on a variety of electronic databases including MEDLINE Ovid, EMBASE, The Cochrane Library of Systematic Reviews and CINHAL.

We developed a comprehensive search strategy to identify all the literature published up to the end of March 2012. The search strategy included a combination of MeSH terms, text words, free text terms and synonyms for integrated care and it also expanded the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC) and included related terms. The EPOC is a Cochrane Review Group focusing on reviews of concepts designed to improve professional practice and the delivery of effective health services and to retrieve overlapping groups we broaden the search by including populations of all ages. The search was not limited to specific concepts, outcomes, language, date or country and we tailored it to identify systematic reviews and meta-analyses using previously validated filters (see appendix) excluding any other design or publication type and restricted it to studies in humans. We ran the search with a full Boolean operation to combine the populations, integrated care concepts and comparisons and study design filters. It included modifications to indexing terms for different databases and was reviewed by the information scientists in the Institute. The full electronic search strategy run in MEDLINE is reported in the appendix.

We also scrutinised extra sources for further identification of studies by hand-searching the reference lists of all included reviews, relevant major review articles and by consulting experts in the team.

Study selection

We selected studies in three stages. First, one author screened the titles and abstracts of all retrieved citations by applying a broad inclusion criterion. At second stage, two authors carried out independent screening of titles and abstracts using the specific inclusion and exclusion criterion reported on the appendix. We ordered the full text of all citations that met the eligibility criteria, appeared relevant, or where relevance/eligibility was not clear from the abstract. In the final screening, two authors independently scrutinised the full texts of studies and recorded the reasons when reviews or meta-analyses were excluded resolving disagreements by discussion and when necessary referred to a third author.

Information and data extraction

We designed and standardised the forms for collection of data and two independent authors pilot-tested them. For each included review, we extracted information for sections on: reference details (author, year, country where study was carried out); aim of the review, topic, whether a meta-analysis was performed or not and the conclusions reached by the review authors; information on the primary studies included in each review (number included, study design, setting and geographic distribution), details on the populations (total number of participants, health status and demographics including chronic condition, age, proportion of males, ethnicity and whether studies included children and), characteristics of the integrated care programmes evaluated (definition, purpose, settings, components, concepts and comparisons, intervention duration and follow up), and outcomes data (outcome type, definitions and measurements, number of primary studies contributing data, number showing/reporting significant improvement and summary of the results per outcome). Data was extracted between two reviewers and double checked by one author resolving disagreements by discussion.

Data synthesis

We analysed the data qualitatively and are summarised and described with a discussion of the total body of evidence and its interpretation. The transferability of the results and the relevance of this study to the Swiss Health Care System are also discussed.

Assessment of integrated care programmes

We appraised the integrated care programmes i.e. the integrated care intervention which were evaluated for their impact on the quality of care, using 10 key elements for successful integration. These elements have been identified by a recent systematic review and represent the key dimensions of organizational integration in health care (Suter 2009). Based on these, we assessed the integrated care concepts studied in each systematic review or meta-analysis to obtain an overall picture of the level, quality and principles associated with successful integration.

Assessment of methodological quality of reviews

We appraised the methodological quality of each systematic review or meta-analysis using AMSTAR an 11-point measurement tool that has good reliability and validity (appendix). We only present a qualitative assessment since we did not perform a formal numerical scoring on the elements of quality.

Two authors carried out independent assessment of the integrated care programmes and the methodological quality of each systematic review or meta-analysis and resolved disagreements by discussion and when necessary referred to a third author.

RESULTS Study retrieval

The flow diagram shows our study selection process and the number of studies included (see appendix). Of 4,008 citations retrieved by the searches, we identified 118 potentially relevant publications and after assessment of full text we excluded 88 with reasons (see appendix).

We initially included a total of 30 studies but excluded two of these at data appraisal stage. Both of these were additional publications of a review originally published in English (Renders 2001) and which had been excluded at an earlier stage because the concepts were not clearly defined as integrated care. One (Bodenheimer 2002) used the review as a substrate and the other (Hansen 2002) was the review translated into Danish. Thus 27 reviews reported in 28 publications were included for assessment.

Characteristics of the included reviews

Characteristics of the 27 reviews are summarised in the appendix.

Of the 28 publications, there were two Cochrane Reviews (Smith 2008, Taylor 2009). One (Smith 2008) of these had a version (Smith 2008) with exactly the same results published in a print journal. We treated these two as one using both as complementary sources.

Of the 27 reviews, twenty six were published in English and one in German.

All but two (Vliet Vlieland 1997, Rich 1998) of the reviews were published from 2001 to 2011. Within this period 60% (15/25) were published from 2005 onwards with a gap in 2010 and the years with the most publications were 2002, 2004, 2008 and 2009.

Based on the title, thirteen reviews were described as systematic (Ouwens 2009, Norris 2002, Mitchel 2008, Mitchell 2002, Adams 2007, McAlister 2001, Lemmens 2011, Lemmens 2008, Smith 2008, Taylor 2009, Niesink 2007, Knight 2005, Ofman 2004), four as meta-analyses (Phillips 2004, Tsai 2005, Weingarten 2002, Elissen 2011), three as systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Göhler 2006, Peytremann-Bridevaux 2008, Gonseth 2004), three as structured, critical or descriptive reviews (Sutherland 2009, Gensichen 2004, Rich 1998), and four did not include systematic review or meta-analysis in their titles but aimed at reviewing the evidence systematically (Badamgarav 2003, Vliet Vlieland 1997, Higginson 2002, Boult 2009). All had a well described and pre-established aim which in general terms consisted of locating and appraising the published evidence on integrated care programmes.

In four of the reviews at least two of the investigators of the same group were authors. The earliest reported (Weingarten 2002) a meta-analysis of various chronic conditions and the other three systematic reviews (Badamgarav 2003 2003, Ofman 2004, Knight 2005) focused solely on one chronic condition from the early report. There were two other reviews of the same first author: one focused on stroke only (Mitchell 2008) and one reported on various conditions except stroke (Mitchell 2002).

diabetes (Elissen 2011) or COPD (Lemmens 2011) and the other reported on both COPD and Asthma (Lemmens 2008). For COPD we included the most complete and largest of the two reviews. The most recent (Lemmens 2011) was an update and included all those studies already appraised and analysed in the older review (Lemmens 2008). Another review (Phillips 2004) was described to complement and expand on the findings by an earlier one (McAlister 2001).

Geographic distribution of the evidence

Of the 27 reviews, 51.85% (14/27) were performed by research groups from European countries including The Netherlands (6), The UK (3), Austria (2), Switzerland (1), Spain (1) and Germany (1). The other 48.15% (13/27) were from North America, 12 from the USA and one from Canada.

The twenty seven reviews appraised a total of 834 studies and the number of studies included ranged from 4 to 112 across reviews.

Only eighteen of the 27 reviews reported the countries where primary studies were conducted and most were from high-income countries. Seventeen of the eighteen reviews included a total of 408 studies: 49.02% (200/408) conducted in the USA and 1 in Puerto Rico, 4.9% (20/408) in Canada, 10.78% in the UK (44/408), 7.84%(32/408) in Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Norway, Finland and Sweden), 15.93% (65/408) in other European countries (Malta, The Netherlands, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece),and the smaller proportion of studies, 10.54% (43/408), were conducted in Australasia, East Asia, Middle East and Latin American countries. In three of the 408 studies (0.74%), the country where these were conducted was not reported. The remaining review stated that the studies were conducted mainly in the USA (Rich 1998). In a few cases, the reviews stated that these details were not available from the primary studies.

Demographics and health status of populations

The age of participants was reported in thirteen of the twenty seven reviews. The participants were mostly middle-aged to elderly and had a mean age of 42 to 80 years in eleven reviews (Elissen 2011, Lemmens 2011, Boult 2009, Taylor 2009, Peytremann-Bridevaux 2008, Adams 2007, Niesink 2007, Göhler 2006, Phillips 2004, Vliet Vlieland 1997, McAlister 2001, Gonseth 2004, Rich 1998). The other three reviews included younger participants who were between 16 and 84 years of age (Badamgarav 2003, Lemmens 2008, Smith 2008).

Three of the twenty seven reviews included primary studies in which some proportion of the participants were children: one included a small sample of 13 children (Elissen 2011), another included one study in children who had a mean age of 9.8 years (Badamgarav 2003) and one more stated to have used material from undergraduate education as part of the intervention programmes (Mitchell 2002).

The gender of the participants was reported in fourteen of the twenty seven reviews. Data was not available from all of the included studies for some of the reviews (Vliet Vlieland 1997, Adams 2007, Gonseth 2004, Elissen 2011, Peytremann-Bridevaux 2008). The proportion of males ranged from 22% to 100% in elven reviews (Elissen 2011, Lemmens 2011, Taylor 2009, Peytremann, Smith 2008, Adams 2007, Niesink 2007, Göhler 2006, Phillips 2004, Gonseth 2004, Vliet Vlieland 1997). Three of

these included one primary study conducted in male populations only (Adams 2007, Niesink 2007, Gonseth 2004) and another included two studies in women only. Another of the fourteen reviews stated to have included one study in women and another in men only (Badamgarav 2003). Of the two remaining reviews, one stated that there were more women (Mitchell 2002) and the other stated that populations were predominantly of mixed gender (Norris 2002).

Limited data were available for ethnicity in only five of the twenty seven reviews. In three reviews, 45 to 97% of the populations were White (Phillips 2004, Taylor 2009, Gonseth 2004). However this proportion is based on 21.4% (15/70) of the included studies in two of these reviews (Taylor 2009, Gonseth 2004). Another review stated that populations were of mixed ethnicity and ranged from ethnic minorities to Caucasians and New Zealand Europeans (Smith 2008). One other review stated that populations were of mixed race including minority groups but a great amount of information from primary studies was missing; and 40% to 77% of the populations were White in eight of the forty two included studies (Norris 2002).

Various chronic conditions were investigated across the reviews. Of the twenty seven reviews, 74% (20/27) focused on participants with only one of the following conditions: diabetes (Elissen 2011, Knight 2005, Norris 2002), heart failure (Taylor 2009, Göhler 2006, Phillips 2004, Gonseth 2004, Gensichen 2004, McAlister 2001, Rich 1998) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Lemmens 2011, Peytremann-Bridevaux 2008, Adams 2007, Niesink 2007), asthma (Lemmens 2008), cancer (Ouwens 2009), rheumatoid arthritis (Badamgarav 2003, Vliet Vlieland 1997), stroke (Mitchell 2008) or progressive threatening illness (Higginson 2002). The other 26% (7/27) reviews included participants from various groups of conditions including asthma, congestive heart failure, diabetes, cancer, angina, patients on osteoarthritis treatment, patients with chronic respiratory disease hypertension, coronary artery disease, back pain and chronic pain, hyperlipidaemia and frail people (Sutherland 2009, Smith 2008, Tsai 2005, Boult 2009, Weingarten 2002, Ofman 2004, Mitchel 2002).

Among all reviews, chronic heart failure (CHF) was the most commonly (12/27) investigated condition (Taylor 2009, Göhler 2006, Phillips 2004, Gonseth 2004, Gensichen 2004, McAlister 2001, Rich 1998, Sutherland 2009, Smith 2008, Tsai 2005, Weingarten 2002, Ofman 2004), followed by diabetes (Elissen 2011, Knight 2005, Norris 2002, Sutherland 2009, Smith 2008, Tsai 2005, Mitchel 2002) and COPD in seven reviews (Lemmens 2011, Peytremann-Bridevaux 2008, Adams 2007, Niesink 2007, Sutherland 2009, Smith 2008, Weingarten 2002); and asthma in four reviews (Lemmens 2008, Smith 2008, Tsai 2005, Mitchel 2002, Weingarten 2002). Cancer (Ouwens 2009, Smith 2008) and rheumatoid arthritis (Badamgarav 2003, Vliet Vlieland 1997) were investigated in only two of the reviews while stroke (Mitchell 2008) and other conditions were rarely reported among the reviews.

Design of studies included

The design and number of included primary studies was reported in twenty four reviews (Elissen 2011, Taylor 2009, Peytremann-Bridevaux 2008, Smith 2008, Niesink 2007, Göhler 2006, Lemmens 2008, Lemmens 2011, Phillips 2004, Gonseth 2004, Mitchell 2002, Badamgarav 2003, Vliet Vlieland 1997, Adams 2007, McAlister 2001, Mitchell 2008, Gensichen 2004, Knight 2005, Boult 2009, Ouwens

Taylor 2009, Smith 2008, Niesink 2007, Göhler 2006, Phillips 2004, McAlister 2001). Of the 663 primary studies included in all twenty four reviews, 73.32% (506/663) were described as RCTs. The remaining 23.68%(157/663) additionally included a variety of other study combinations, e.g. quasi randomised trials, controlled clinical trials, prospective single blinded controlled trials, before and after studies, controlled trials, cross-sectional, observational, qualitative and descriptive studies, pilot scheme before and after studies.

Sample sizes from primary studies were available from nineteen reviews. These ranged from 669 to 18378 with a mean of 6380.65 patients in seventeen reviews. In another review this information was available from RCTs (N=631) only (Mitchel 2008) and from 30 of 32 (N=8686) studies in another (Adams 2007).

Quantitative analyses were performed in eighteen of the twenty seven reviews. All of these used meta-analysis tools to pool data on various outcomes across studies (Elissen 2011, Lemmens 2011, Taylor 2009, Peytremann-Bridevaux 2008, Lemmens 2008, Smith 2008, Adams 2007, Göhler 2006, Tsai 2005, Knight 2005, Phillips 2004, Ofman 2004, Gonseth 2004, Gensichen 2004, Badamgarav 2003, Higginson 2002, Weingarten 2002, McAlister 2001). Data across reviews were reported in various forms and the neither confidence intervals nor significance values were always reported. We therefore present a summary of findings where it was possible to obtain per condition and outcome on Appendix.

Settings of care

Information on the settings where the primary studies were conducted was available from all but four reviews (Weingarten 2002, Mitchell 2002, Gensichen 2004) and included a wide variety from inpatients to outpatients, ambulatory, discharge, nursing homes, rehabilitation centres, community, secondary and semi-rural country hospitals, home care and referral (Elissen 2011, Taylor 2009, Peytremann-Bridevaux 2008, Smith 2008, Adams 2007, Niesink 2007, Göhler 2006, Lemmens 2008, Lemmens 2011, Phillips 2004, Gonseth 2004, Badamgarav 2003, Vliet Vlieland 1997, Ofman 2004, Norris 2002, McAlister 2001, Mitchell 2008, Knight 2005, Boult 2009, Ouwens 2009, Sutherland 2009).

Assessment of methodological quality

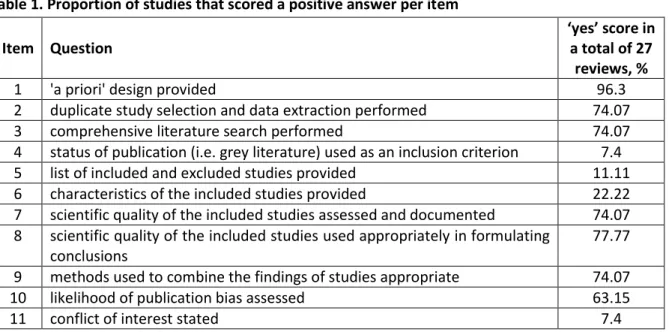

In general, the methodological quality of the twenty seven systematic reviews and meta-analyses included could be described as medium as they addressed an average of only 5.59 of the eleven criteria set out in the AMSTAR tool. However, the quality varied widely as the number of elements with a positive answer across reviews ranged from 0 to 10. Of the twenty seven reviews only seven were of highest quality by scoring a positive answer in 8 to 10 items (Taylor 2009, Smith 2008, Adams 2007, Peytremann-Bridevaux 2008, Phillips 2004, Gonseth 2004, Higginson 2002). Other twelve reviews scored positively on 5 to 7 items, eight scored 1 to 4 items and one review did not score positively in any of the criteria.

Only sixteen of the twenty seven reviews had a clear research question, a method for duplicate study selection and data extraction and performed a comprehensive literature search (Questions 1-3) (Elissen 2011, Taylor 2009, Ouwens 2009, Peytremann-Bridevaux 2008, Smith 2008, Mitchell 2008, Adams 2007, Niesink 2007, Knight 2005, Ofman 2004, Gonseth 2004, Badamgarav 2003, Higginson 2002, Norris 2002, Weingarten 2002, McAlister 2001). However many of these did not described the publication status in their inclusion criteria, did not report on the likelihood of publication bias, did not described in good detail the characteristics of participants from primary studies, did not include the lists of both included and excluded studies and did not state the potential conflict of interest for both the primary studies. For one review all the aspects of quality were difficult to assess or not reported (Rich 1998 1998).

In summary, the main weaknesses in the reviews were as follows: publication status used as an inclusion criterion had a positive score in only two reviews (Smith 2008, Higginson 2002); the lists of included and excluded studies reported in only three reviews (Taylor 2009, Smith 2008, Gonseth 2004); the description of the characteristics of the included studies and populations scored positively in only six reviews (Taylor 2009, Peytreman-Bridevaux 2008, Lemmens 2008, Smith 2008, Adams 2007, Phillips 2004); the conflict of interests for both the primary studies included in the reviews and the reviews themselves was stated in only two reviews (Taylor 2009, Phillips 2004); and the likelihood of publication bias was assessed and reported in twelve of the nineteen reviews in which this was applicable. Although eighteen of the twenty seven reviews integrated a meta-analysis and combined findings with appropriate methods only ten assessed the likelihood of publication bias. Also, selection bias is evident in one of the reviews although the selective criterion for inclusion of studies focused purely on “successful” models of care was defined ‘a-priori’ (Boult 2009).

Table 1 summarises the quality showing the proportion of reviews that scored a positive answer per item. The full assessment of the quality of the included reviews is reported in the Appendix.

Table 1. Proportion of studies that scored a positive answer per item Item Question

‘yes’ score in a total of 27

reviews, %

1 'a priori' design provided 96.3

2 duplicate study selection and data extraction performed 74.07

3 comprehensive literature search performed 74.07

4 status of publication (i.e. grey literature) used as an inclusion criterion 7.4

5 list of included and excluded studies provided 11.11

6 characteristics of the included studies provided 22.22

7 scientific quality of the included studies assessed and documented 74.07

8 scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions

77.77

9 methods used to combine the findings of studies appropriate 74.07

10 likelihood of publication bias assessed 63.15

11 conflict of interest stated 7.4

Table 2. Summary of key principles associated with successful integration identified in the reviews

Item Key element for integrated care Studies, n

I Comprehensive services across the care continuum 26

II Patient focus 22

III Geographic coverage and rostering 1

IV Standardized care delivery through interprofessional teams 25

V Performance management 17

VI Information systems 13

VII Organizational culture and leadership 5

VIII Physician integration 15

IX Governance structure 1

Integrated care programmes and concepts

A variety of models and components of integrated care have been reported in the twenty seven reviews. Several terms were used to map the definition of integrated care and disease management was the most frequently used (Lemenns 2008, Niesink 2007, Göhler 2006, Knight 2005, Ofman 2004, Gonseth 2004, Badamgarav 2003, Weingarten 2002, McAlister 2001, Norris 2002, Peytremann-Bridevaux 2008). Other terms included case management (Sutherland 2009, Gensichen 2004, Norris 2002, Taylor 2009, Peytremann-Bridevaux 2008), shared care (Smith 2008), managed care (Mitchell 2002), comprehensive care (Phillips 2004), multidisciplinary care (Ouwens 2009, Taylor 2009, Mitchell 2008, Rich 1998, Vliet Vlieland 1997), organised and coordinated care (Ouwens 2009, Mitchell 2002), team care (Higginson 2002), managed care cooperation (Mitchell 2002) and chronic care model (Elissen 2011, Lemmens 2011, Adams 2007, Tsai 2005, Boult 2009). However, behind these general terms there was a large variety of different integrated care concepts. To further appraise these concepts, we used ten key elements of successful care integration (Suter 2009). Table 2 summarises assessment of the integrated care concepts showing the proportion of reviews per item. The full assessment of the quality of the included reviews is reported in the Appendix. The most frequently identified elements in almost all of the reviews were (1) comprehensive services across the care continuum, (2) patient focus and (3) standardized care delivery through interprofessional teams. Performance management, information systems and physician integration were identified in half of the twenty-seven reviews. Of all reviews, we identified between five and more elements in fifteen reviews and four and less elements in twelve reviews. Particularly important seems the lack of focus on “Organizational culture and leadership” as well as on “Governance structure”.

Effectiveness of integrated care concepts

The effect of integrated care on patient-centred outcomes such as quality of life and patient satisfaction were the most frequently reported. Sixteen of the twenty-seven reviews assessed quality of life: six in chronic heart failure, five in COPD, four in diabetes, two in asthma and four other reviews in one other condition each including, stroke, angina and progressive life threatening conditions. For CHF, diabetes and asthma, the reviews showed mixed results with improvement only in a small number of studies (Gensichen 2004, Knight 2005, Norris 2002, Phillips 2004, Rich 1998, Sutherland 2009, Tsai 2005, Taylor 2009, Lemmens 2008). There was a positive trend towards improvement of quality of life in patients with COPD in favour of the intervention group (Adams 2007, Lemmens 2011, Niesink 2007, Peytremann-Bridevaux 2008 2008, Sutherland 2009). Patient satisfaction was appraised in five reviews and three reported significant improvement in the integrated care groups of diabetes patients (Norris 2002, Sutherland 2009, Mitchell). However, these findings were limited by both the small number of primary studies contributing to this improvement and the lack of reported numeric results. Two other reviews in CHF patients found higher satisfaction levels in the intervention group but only one study in each review contributed to this improvement (Sutherland 2009, Rich 1998). Four other reviews on cancer, hypertension, angina or progressive life threatening conditions reported mostly positive effects on patient information and satisfaction (Ouwens 2009, Higginson 2002, Sutherland 2009, Mitchell 2002). These findings were also limited by the small number of studies and by the inconclusive evidence of significant effects associated with

integrated care found in cancer patients. None of the reviews assessed the effect on patient satisfaction in COPD or Asthma.

Ten of the twenty-seven reviews evaluated the effect of integrated care concepts on mortality and status of functional capacity. For patients with COPD, no beneficial effect on mortality was observed in three reviews (Adams 2007, Lemmens 2011, Peytremann-Bridevaux 2008). Mixed results were obtained in five reviews for patients with CHF: one meta-analysis stated significant reduction of mortality at six months whereas another meta-analysis did not reach significant difference (Gensichen 2004, Göhler 2006, Phillips 2004, McAllister, Taylor 2009). Other functional outcomes such as exercise capacity, functional status and the capacity to perform daily activities were shown to be significantly ameliorated in patients with CHF (Gensichen 2004, Rich 1998) and in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (Badamgarav 2003, Vliet Vlieland 1997). In contrast, three reviews have reported only mixed results regarding the effect of integrated care concepts on exercise capacity (walking test) and functional tests (FEV1) in COPD patients (Adams 2007, Peytremann-Bridevaux 2008, Sutherland 2009). For patients with diabetes, asthma and stroke there was only one study in each review contributing to a significant improvement in functional status, disability and functional tests (Norris 2002 2002, Lemmens 2008, Mitchell 2008). The same was the case for physical health measures such as functional tests (FEV1) for various conditions in another review (Smith 2008). Significantly improved glycaemic control (HbA1c and glucose levels) associated to integrated care was reported in six reviews (Elissen 2011, Knight 2005, Mitchell 2002, Norris 2002, Sutherland 2009, Tsai 2005). Other outcomes included better provider performance to screen for symptoms associated with diabetes such as retinopathy, neuropathy and nephropathy and significant better self-monitoring of blood glucose although the number of primary studies contributing for this was small (Elissen 2011, Knight 2005, Mitchell 2002, Norris 2002, Sutherland 2009, Tsai 2005). One review on cancer patients included 2 studies showing that case management can lead to significant improvements of morbidity (Ouwens 2009). Another review found significant improvement for disease control in patients with hyperlipidaemia and with hypertension from a small number of studies (Ofman 2004). Finally, only one study in one more review on patients with CHF showed an improvement in low density lipoprotein but not in blood pressure (Sutherland 2009).

Significant improvement of compliance with medications and diet, adherence to treatment and to guidelines was reported for patients with diabetes in four reviews (Elissen 2011, Mitchell 2002, Sutherland 2009, Tsai 2005) and for patients with hyperlipidaemia in one review (Ofman 2004). Mostly significant improvements of these outcomes were stated for CHF and COPD patients in six reviews (Gensichen 2004, Peytremann-Bridevaux 2008, Ofman 2004, Rich 1998, Sutherland 2009, Tsai 2005). Two other reviews reported mixed results in patients with asthma (Tsai 2005, Lemmens, 2008). One of these showed significant improvement from thirteen studies on self-management-behaviour, compliance and patient knowledge (Lemmens 2008) whereas the other showed uncertain benefits from two primary studies prescription of medication (Tsai 2005). Another review found significant benefits with appropriate prescribing and compliance with medication for patients under treatment for oral anticoagulant therapy (OAT), diabetes and CHF but these findings were supported by only one primary study (Smith 2008 2008). No effect on adherence to treatment and guidelines has been consistently reported for patients with coronary heart disease, hyperlipidemia and hypertension by one review (Ofman 2004).

Two other reviews described the effects of integrated care on various outcomes by models of care (Boult 2009, Weingarten 2002). One of these summarised the effect of “successful” models of comprehensive care on health related outcomes including quality of care, quality of life, functional autonomy and survival Use/Cost of Health Services (Boult 2009). Based on fifteen models of care identified from RCTs, quasi experimental and cross-sectional studies, the review showed an improvement in at least one of these outcomes. The other review evaluated the effect of integrated care on health outcomes related to the control of disease such as FEV1, reinfarction, HbA1c, HLPD, LDL, and cholesterol concentration and the adherence to guidelines (e.g. blocker prescribing rate, funduscopy performed, screening for retinal complications, screening for renal complications, screening for foot lesions, HbA1c test performed, etc.) (Weingarten 2002). Based on 118 programs identified from trials the review showed improvements in these outcomes from at least one of the programs evaluated.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this review was to synthesise the evidence of the effectiveness of integrated care programmes in the care of adult patients with chronic conditions from published systematic reviews and meta-analyses. This implied to appraise a large body of highly heterogeneous data regarding patient population, medical conditions and concepts of integrated care. Most of the evidence comes from empirical studies mainly RCTs (506/663) and despite heterogeneity, we identified significant improvements of integrated care on patient outcomes: there is solid evidence for higher patient satisfaction in diabetes and to a lesser degree for CHF patients, better functional capacity in CHF patients as well as significant amelioration of disease control and compliance with treatment and guidelines in patients with diabetes. In contrast, inconclusive or no evidence was found for the effect of integrated care on quality of life in patients with CHF, diabetes, COPD and asthma as well as on mortality of patients with CHF or COPD.

The studies included in our review assessed a broad variety of concepts of integrated care. In order to clarify the effectiveness of these concepts we intended to identify the nature of the concepts. However, it was difficult to extract precise information from many studies with regards to type of control/comparisons, team delivering the intervention, length of follow up, frequency and duration. Ouwens et al. have suggested that failure to recognize appropriately the varying definitions and nature of integrated care concepts may lead to false conclusions about the effectiveness of integrated care concepts (Ouwens 2005). Using a set of ten key elements of successful care integration, we identified “comprehensive services across the care continuum”, “patient focus” and “standardised care delivery through interprofessional teams” as the most frequently evaluated elements of integrated care (Suter 2009). As Suter et al. have suggested, successfully integrated delivery systems combine many if not all of the ten key elements (Suter 2009). It is therefore noteworthy that in twelve of the reviews only a small number of these elements could be identified. These findings suggest that many initiatives to integrate health services follow a too selective approach and have a too narrow focus. An important driving force for strong fragmentation in health care are diverse cultures, rigid differentiation and distinct mindsets between the various sectors of health care such as between ambulatory and inpatient service providers or between general practitioners and specialized physicians (Glouberman 2001). Bringing diverse cultures and distinct mindsets together requires strong leadership taking up a clear stance on integration and promoting ownership among staff (Campbell 1998, Porter 2007). Integrating health services also means to bring more accountability to networks of partly independent health professionals requiring governance structures which foster coordination and decision-making throughout the delivery organisation (Plsek 2001).

Overall, the reviews evaluated are limited by the amount of descriptive information and data provided in the primary studies. Factors making comparison between studies difficult include insufficient details on demographic information, the nature of the programmes and concepts. For example, the reporting of gender and ethnicity was very poor among reviews. A minimum amount of demographic information should be reported including, age, gender, race or ethnicity, and type of condition. The quality of reporting remains of high importance for the interpretation and transferability of findings. Moreover, many of the reviews lacked basic and important elements of a

systematic process including the use of publication status as an inclusion criterion, reporting of lists of included and excluded studies, the description of the characteristics of primary studies and populations, the likelihood of publication bias and missing statements on the conflict of interest.

LIMITATIONS

Various concepts of integrated care with multiple disease categories were studied in this review and comparative analyses can only be performed for generic outcomes such as quality of life, patient satisfaction, or disease unspecific indicators of process quality such as provider adherence to guidelines. The review can therefore provide only disease specific conclusions on effects of integrated care and general conclusions are not possible.

The review was focused on patient and clinical outcomes. The results of specific studies on cost efficiency of integrated care programmes and on health care utilisation were not included. Further research is therefore needed to provide more conclusive evidence on the overall cost and effectiveness of integrated care.

The review is based on primary studies mainly RCTs from a variety of countries with health systems differing from Swiss health care, an immediate translation of findings for Swiss health care remains limited.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our systematic review shows significant although variable effectiveness of integrated care programmes for patients with chronic conditions. However the various concepts and programmes of integrated care evaluated in the literature include a wide variety of components limiting the comparability between studies. Moreover, our review demonstrates that many initiatives and programmes of integrated care follow a too selective approach. Failure to include important dimensions for integrating health services such as "organizational culture and leadership" and "governance structure" may reduce the effectiveness of such programmes. Organisations that successfully integrate their health services align with and support the key dimensions of integration.

REFERENCES

Reference list of included studies

1. Adams, S. G., P. K. Smith, et al. (2007). "Systematic review of the chronic care model in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevention and management (Structured abstract)." Archives of Internal Medicine(6): 551-561.

2. Badamgarav, E., J. D. Croft Jr, et al. (2003). "Effects of disease management programs on functional status of patients with rheumatoid arthritis." Arthritis Care and Research 49(3): 377-387.

3. Boult, C., A. F. Green, et al. (2009). "Successful models of comprehensive care for older adults with chronic conditions: evidence for the institute of medicine's "Retooling for an aging America" report." Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 57(12): 2328-2337.

4. Elissen, A. M., L. M. Steuten, et al. (2012). "Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of chronic care management for diabetes: Investigating heterogeneity in outcomes." Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice.

5. Gensichen, J., M. Beyer, et al. (2004). "Primary Case based Case Management for Patients with Congestive Heart Failure - A critical review." Zeitschrift fur Arztliche Fortbildung und Qualitatssicherung 98(2): 143-154.

6. Gohler, A., J. L. Januzzi, et al. (2006). "A Systematic Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy and Heterogeneity of Disease Management Programs in Congestive Heart Failure." Journal of Cardiac Failure 12(7): 554-567.

7. Gonseth, J., P. Guallar-Castillon, et al. (2004). "The effectiveness of disease management programmes in reducing hospital re-admission in older patients with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of published reports." European Heart Journal 25(18): 1570-1595. 8. Higginson, I. J., I. Finlay, et al. (2002). "Do hospital-based palliative teams improve care for

patients or families at the end of life?" J Pain Symptom Manage 23(2): 96-106.

9. Knight, K., E. Badamgarav, et al. (2005). "A systematic review of diabetes disease management programs." American Journal of Managed Care 11(4): 242-250.

10. Lemmens, K. M., A. P. Nieboer, et al. (2009) "A systematic review of integrated use of disease-management interventions in asthma and COPD (Structured abstract)." Respiratory Medicine, 670-691.

11. Lemmens, K. M. M., L. C. Lemmens, et al. (2011). "Chronic care management for patients with COPD: A critical review of available evidence." Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice.

12. McAlister, F. A., F. M. Lawson, et al. (2001). "A systematic review of randomized trials of disease management programs in heart failure." American Journal of Medicine 110(5): 378-384.

13. Mitchell, G., C. Del Mar, et al. (2002). "Does primary medical practitioner involvement with a specialist team improve patient outcomes? A systematic review." British Journal of General Practice 52(484): 934-939.

14. Mitchell, G. K., R. M. Brown, et al. (2008). "Multidisciplinary care planning in the primary care management of completed stroke: a systematic review." BMC Family Practice 9: 44.

15. Niesink, A., J. C. A. Trappenburg, et al. (2007). "Systematic review of the effects of chronic disease management on quality-of-life in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease." Respiratory Medicine 101(11): 2233-2239.

16. Norris, S. L., P. J. Nichols, et al. (2002). "The effectiveness of disease and case management for people with diabetes: A systematic review." American Journal of Preventive Medicine 22(4 SUPPL. 1): 15-38.

17. Ofman, J. J., E. Badamgarav, et al. (2004). "Does disease management improve clinical and economic outcomes in patients with chronic diseases? A systematic review." American Journal of Medicine 117(3): 182-192.

18. Ouwens, M., M. Hulscher, et al. (2009). "Implementation of integrated care for patients with cancer: A systematic review of interventions and effects." International Journal for Quality in Health Care 21(2): 137-144.

19. Peytremann-Bridevaux, I., P. Staeger, et al. (2008) "Effectiveness of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-management programs: systematic review and meta-analysis (Structured abstract)." American Journal of Medicine, 433-443,e434.

20. Phillips, C. O., S. M. Wright, et al. (2004). "Comprehensive discharge planning with postdischarge support for older patients with congestive heart failure: a meta-analysis." JAMA 291(11): 1358-1367.

21. Rich, M. W. (1999). "Heart failure disease management: A critical review." Journal of Cardiac Failure 5(1): 64-75.

22. Smith, S. M., S. Allwright, et al. (2008) "Does sharing care across the primary-specialty interface improve outcomes in chronic disease? A systematic review (Brief record)." American Journal of Managed Care, 213-224.

23. Smith Susan, M., S. Allwright, et al. (2007) "Effectiveness of shared care across the interface between primary and specialty care in chronic disease management." Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004910.pub2.

24. Sutherland, D. and M. Hayter (2009). "Structured review: evaluating the effectiveness of nurse case managers in improving health outcomes in three major chronic diseases." Journal of Clinical Nursing 18(21): 2978-2992.

25. Taylor Stephanie, J. C., C. Bestall Janine, et al. (2005) "Clinical service organisation for heart failure." Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002752.pub2. 26. Tsai, A. C., S. C. Morton, et al. (2005). "A meta-analysis of interventions to improve care for

chronic illnesses." American Journal of Managed Care 11(8): 478-488.

27. Vliet Vlieland, T. P. and J. M. Hazes (1997). "Efficacy of multidisciplinary team care programs in rheumatoid arthritis." Semin Arthritis Rheum 27(2): 110-122.

28. Weingarten, S. R., J. M. Henning, et al. (2002). "Interventions used in disease management programmes for patients with chronic illness-which ones work? Meta-analysis of published reports." BMJ 325(7370): 925.

Other references cited in the manuscript

1. Berchtold, P. and I. Peytremann-Bridevaux (2011). "Integrated care organizations in Switzerland." Int J Integr Care 11 Spec Ed: e010.

2. Campbell, H., R. Hotchkiss, et al. (1998). "Integrated care pathways." Bmj 316(7125): 133-137. 3. Glouberman, S. and H. Mintzberg (2001). "Managing the care of health and the cure of

disease--Part I: Differentiation." Health Care Management Review 26(1): 56-69; discussion 87-59.

4. Grol, R. (2000). "Between evidence-based practice and total quality management: the implementation of cost-effective care." Int J Qual Health Care 12(4): 297-304.

5. Leape, L., D. Berwick, et al. (2009). "Transforming healthcare: a safety imperative." Qual Saf Health Care 18(6): 424-428.

6. Plsek, P. E. and T. Wilson (2001). "Complexity, leadership, and management in healthcare organisations." Bmj 323(7315): 746-749.

7. Porter, M. E. and E. O. Teisberg (2007). "How physicians can change the future of health care." JAMA 297(10): 1103-1111.

8. Strandberg-Larsen, M. and A. Krasnik (2009). "Measurement of integrated healthcare delivery: a systematic review of methods and future research directions." Int J Integr Care 9: e01

References for the search filters used for the identification of systematic reviews or meta-analyses 1. The University of Texas, School of Public Health: Search filters for systematic reviews and

meta-analyses. Accessed 25 Nov 2011. [Ovid, PubMed]. https://sph.uth.tmc.edu/current-students/library/search-filters/

2. Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB, Hedges Team. EMBASE search strategies achieved high sensitivity and specificity for retrieving methodologically sound systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2007;60(1):29-33. [Ovid]. BMJ Clinical Evidence strategy [undated] [Ovid]. http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com/x/set/static/ebm/learn/665076.html

Reference list of excluded studies

1. Agencia de Evaluacion de Tecnologias, S. (2005) "Utilization of information and communication technology in managing chronic diseases: a systematic review IPE-05/45 (Public report) (Structured abstract)." Madrid: Agencia de Evaluacion de Tecnologias Sanitarias (AETS).

2. Alberts, M. J., G. Hademenos, et al. (2000). "Recommendations for the establishment of primary stroke centers." Journal of the American Medical Association 283(23): 3102-3109.

3. Ann McKibbon, K., C. Lokker, et al. (2012). "The effectiveness of integrated health information technologies across the phases of medication management: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials." Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 19(1): 22-30.

4. Atun, R., T. E. de Jongh, et al. (2011). "Integration of priority population, health and nutrition interventions into health systems: systematic review." BMC public health 11: 780.

5. Belanger, E. and C. Rodriguez (2008). "More than the sum of its parts? A qualitative research synthesis on multi-disciplinary primary care teams." Journal of Interprofessional Care 22(6): 587-597.

6. Blaiss, M. S. (2005). "Asthma disease management: A critical analysis." Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology 95(5 SUPPL. 1): S10-S16.

7. Bodenheimer, T. (2003). "Interventions to improve chronic illness care: Evaluating their effectiveness." Disease Management 6(2): 63-71.

8. Bodenheimer, T., K. Lorig, et al. (2002). "Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care." JAMA 288(19): 2469-2475.

9. Bodenheimer, T., E. H. Wagner, et al. (2002). "Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness." Journal of the American Medical Association 288(14): 1775-1779.

10. Bott, D. M., M. C. Kapp, et al. (2009). "Disease management for chronically ill beneficiaries in traditional Medicare." Health Affairs 28(1): 86-98.

11. Boulet, L. P. (2008). "Improving knowledge transfer on chronic respiratory diseases: a Canadian perspective. How to translate recent advances in respiratory diseases into day-to-day care." Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging 12(10): 758S-763S.

12. Bourbeau, J. (2003) "Disease-specific self-management programs in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a comprehensive and critical evaluation (Structured abstract)." Disease Management and Health Outcomes, 311-319.

13. Boyd, C. M., J. Darer, et al. (2005). "Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance." JAMA 294(6): 716-724.

14. Bravata, D. M., A. L. Gienger, et al. (2009). "Quality improvement strategies for children with asthma: A systematic review." Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 163(6): 572-581. 15. Brouwers, M., T. K. Oliver, et al. (2009). "Cancer diagnostic assessment programs: Standards for

the organization of care in Ontario." Current Oncology 16(6): 29-41.

16. Cerimele, J. M. and J. J. Strain (2010). "Integrating primary care services into psychiatric care settings: A review of the literature." Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 12(6).

17. Chaudhry, S. I., C. O. Phillips, et al. (2007). "Telemonitoring for patients with chronic heart failure: a systematic review." Journal of Cardiac Failure 13(1): 56-62.

18. Chin, M. H. (2010). "Quality improvement implementation and disparities: the case of the health disparities collaboratives." Medical Care 48(8): 668-675.

19. Chiu, W. K. and R. Newcomer (2007). "A systematic review of nurse-assisted case management to improve hospital discharge transition outcomes for the elderly." Professional case management 12(6): 330-336; quiz 337-338.

20. Chodosh, J., S. C. Morton, et al. (2005). "Improving patient care. Meta-analysis: chronic disease self-management programs for older adults." Annals of Internal Medicine 143(6): 427.

21. Cochran, J. (2007). Meta-analysis of quality of life outcomes following diabetes self-management training. Ph.D., University of Missouri - Columbia.

22. Coleman, K., B. T. Austin, et al. (2009). "Evidence on the Chronic Care Model in the new millennium." Health Affairs 28(1): 75-85.

23. Conklin, A. a. N., E (2011). Disease Management Evaluation. A Comprehensive Review of Current State of the Art, Cambridge: The RAND Corporation.

24. Courtenay, M. and N. Carey (2008). "The impact and effectiveness of nurse-led care in the management of acute and chronic pain: A review of the literature." Journal of Clinical Nursing 17(15): 2001-2013.

25. Cunningham, F. C., G. Ranmuthugala, et al. (2012). "Health professional networks as a vector for improving healthcare quality and safety: A systematic review." BMJ Quality and Safety 21(3): 239-249.

26. Currell, R., C. Urquhart, et al. (2000). "Telemedicine versus face to face patient care: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes." Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(2): CD002098.

27. Dancer, S. and M. Courtney (2010). "Improving diabetes patient outcomes: framing research into the chronic care model." Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 22(11): 580-585.

28. de Bruin, S. R., C. A. Baan, et al. (2011). "Pay-for-performance in disease management: a systematic review of the literature." BMC Health Services Research 11: 272.

29. De Bruin, S. R., R. Heijink, et al. (2011). "Impact of disease management programs on healthcare expenditures for patients with diabetes, depression, heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review of the literature." Health Policy 101(2): 105-121.

30. Effing, T., E. M. Monninkhof Evelyn, et al. (2007) "Self-management education for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease." Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002990.pub2.

31. Ehrlich, C., E. Kendall, et al. (2009). "Coordinated care: what does that really mean?" Health & Social Care in the Community 17(6): 619-627.

32. Eklund, K. and K. Wilhelmson (2009). "Outcomes of coordinated and integrated interventions targeting frail elderly people: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials." Health & Social Care in the Community 17(5): 447-458.

33. Freund, T., F. Kayling, et al. (2009) "Effectiveness and efficiency of primary care based case management for chronic diseases: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized trials. (Protocol for a systematic review) (Structured abstract)." HTA Database, Crd32009100316.

34. Frich, L. M. H. (2003). "Nursing interventions for patients with chronic conditions." Journal of Advanced Nursing 44(2): 137-153.

35. Gohler A, O. Z., Siebert V (2004). "Long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of disease management programs in congestive heart failure a decision-analytic view." Circulation 110(S III): 639.

36. Greenhalgh, P. M. (1994). "Shared care for diabetes. A systematic review." Occas Pap R Coll Gen Pract(67): i-viii, 1-35.

37. Greenhalgh, P. M. (1994) "Shared care for diabetes: a systematic review (Structured abstract)." Royal College of General Practitioners, 35.

38. Griffiths Peter, D., E. Edwards Margaret, et al. (2007) "Effectiveness of intermediate care in nursing-led in-patient units." Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002214.pub3.

39. Gruen, R., T. Weeramanthri, et al. (2006). "Specialist outreach clinics in primary care and rural hospital settings (Cochrane Review)." Community Eye Health 19(58): 31.

40. Grundel, B. L., G. L. White, Jr., et al. (1999). "Diabetes in the managed care setting: a prospective plan." Southern Medical Journal 92(5): 459-464.

41. Guzman, J., R. Esmail, et al. (2002). "Multidisciplinary bio-psycho-social rehabilitation for chronic low back pain." Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(1): CD000963.

42. Guzman, J., R. Esmail, et al. (2007). "WITHDRAWN: Multidisciplinary bio-psycho-social rehabilitation for chronic low-back pain." Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online)(3): CD000963.

43. Hansen, L. J. and T. B. Drivsholm (2002). "[Interventions to improve the management of diabetes mellitus in primary health care and outpatient community settings]." Ugeskrift for Laeger 164(5): 607-609.

44. Hayes Sara, L., K. Mann Mala, et al. (2011) "Collaboration between local health and local government agencies for health improvement." Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007825.pub5.

45. Hearn, J. and I. J. Higginson (1998). "Do specialist palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients? A systematic literature review." Palliat Med 12(5): 317-332.

46. Hickman, L., P. Newton, et al. (2007). "Best practice interventions to improve the management of older people in acute care settings: a literature review." Journal of Advanced Nursing 60(2): 113-126.

47. Higginson, I. J., I. G. Finlay, et al. (2003). "Is there evidence that palliative care teams alter end-of-life experiences of patients and their caregivers?" Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 25(2): 150-168.

48. Inglis Sally, C., A. Clark Robyn, et al. (2010) "Structured telephone support or telemonitoring programmes for patients with chronic heart failure." Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007228.pub2.

49. Inglis, S. C., R. A. Clark, et al. (2011). "Which components of heart failure programmes are effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the outcomes of structured telephone support or telemonitoring as the primary component of chronic heart failure management in 8323 patients: Abridged Cochrane Review." European Journal of Heart Failure 13(9): 1028-1040. 50. Inglis, S. C., S. Pearson, et al. (2006) "Extending the horizon in chronic heart failure: effects of

multidisciplinary, home-based intervention relative to usual care (Provisional abstract)." Circulation, 2466-2473.