Sleep of Excessively Crying Infants: A 24-Hour Ambulatory Sleep

Polygraphy Study

Jarkko Kirjavainen, MD*; Liisa Lehtonen, MD‡; Turkka Kirjavainen, MD§; and Pentti Kero, MD‡

ABSTRACT. Objective. Parents’ reports suggest that excessively crying or colicky infants sleep less compared with control subjects. The aim of this study was to de-termine the sleep-wake structure of excessively crying infants throughout a 24-hour cycle.

Methods. A 24-hour sleep polygraphy study was con-ducted at home for 24 excessively crying infants and 23 control subjects at the age of 6 weeks. In addition, pa-rental diaries were kept for 4 days.

Results. In sleep polygraphy recordings, no major differences between study groups were observed in ei-ther the duration or the structure of the 24-hour sleep. In the diaries, the parents overestimated the amount of sleep in both study groups. The parents of the control infants overestimated the amount of sleep more than the parents of excessively crying infants (69.8 minutes dard deviation: 79.3] compared with 27.1 minutes [stan-dard deviation: 65.4], respectively). In excessively crying infants, the proportion of rapid eye movement sleep was higher during the 3-hour period from the beginning of the first long sleep in the evening and lower during the preceding 3-hour period compared with the control group.

Conclusions. The results of this study suggest that diary-based studies are prone to be biased as the parents of the control infants are more likely to overestimate the amount of infant’s sleep and, therefore, report more sleep than the parents of the crying infants. Although no differences in the total amount of sleep or propor-tions of sleep stages were observed, excessively crying infants may be characterized by a disturbance that affects rapid eye movement and non–rapid eye movement sleep stage proportion during evening hours.Pediatrics2004; 114:592–600;cry, infant, infantile colic, sleep, polysomnog-raphy, rapid-eye-movement sleep, behavioral states.

ABBREVIATIONS. REM, rapid eye movement; NREM, non–rapid eye movement; EEG, electroencephalogram; EMG, electromyogram.

C

rying in early infancy has a tendency to in-crease after birth.1–3When the amount of cry-ing is at its maximum, a proportion of infants cry more than is tolerated by the caregivers. Infants who cry⬎3 hours a day for 3 days or more a weekare referred to as colicky infants.4No organic cause can be demonstrated in the vast majority of these infants, and they recover from the crying period without any obvious consequences.5

Crying episodes tend to cluster in the evenings, especially at the age of high amounts of crying.2 Simultaneously, the development of sleep goes through rapid changes. At the age from 2 weeks to 3 months, infant’s sleep-wake rhythm changes from regular 4-hour cycles to a well-defined day-night rhythm. The longest awake period tends to occur during evening hours6,7at the time when infants also cry the most.3 During the same time period, the structure of sleep changes. Neonatal sleep character-istics such as sleep onset with rapid eye movement (REM) periods rapidly subside after the age of 4 to 5 weeks, and the variable length of REM and non– rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep cycle length sta-bilizes at 4 months of age.8 During the night, the REM and NREM ratio decreases by increasing age.9 The coincidence of these phenomena suggests that excessive crying in infancy may be associated with disturbances in the developing sleep structure or sleep-wake rhythm.

An association between colic and later sleep prob-lems originally received support from questionnaire studies in which mothers who reported sleep prob-lems also recalled more colic in their children retro-spectively,10,11and mothers who reported more colic reported more sleep problems prospectively in their children at 3 years of age.12 These results are con-fronted by our later prospective study of colicky infants using daily diaries to document the amount of crying. It did not show any differences in the duration of night sleep, amount of night awakenings, duration of night awakenings, or day time sleep at either 8 or 12 months of age.13This finding has been confirmed by a recent study by Canivet et al.14

Diary-based studies during colic have suggested that the total daily sleep time is shorter in colicky infants compared with control subjects. St James Roberts et al15reported that the total daily sleep time was 77 minutes shorter in the group of excessively crying infants compared with control subjects at 6 weeks of age. When the 24-hour day was split into 6-hour quartiles, the difference was observed only during daytime (between 6 am and noon). Prud-homme et al16 showed that 2-month-old colicky in-fants slept 2 hours less per day than control inin-fants. In a study by Papousˇek and von Hofacker,17 exces-sively crying infants slept 93 minutes per day less than control subjects at the age of 3.6 months. In our

From the Departments of *Pediatric Neurology and Clinical Neurophysiol-ogy and ‡Pediatrics, Turku University Hospital, Turku, Finland; and §De-partment of Pediatrics, Hospital for Children and Adolescents, Helsinki, Finland.

Accepted for publication Feb 17, 2004. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2003-0651-L

Reprint requests to (J.K.) Department of Pediatric Neurology, Central Hos-pital of Central Finland, Keskussairaalantie 19, 40620 Jyva¨skyla¨, Finland. E-mail: jarkko.kirjavainen@utu.fi

earlier study, the diary data at 5 weeks of age showed 108 minutes less sleep a day in the group of excessively crying infants compared with the control subjects. There was less reported sleep during each quartile of the day, but the difference was statisti-cally significant only during evening hours and nighttime. However, this difference was not ob-served in later overnight sleep polygraphy record-ings of the same infants in a sleep laboratory at 2 or 7 months of age.18

Wolff19 proposed that crying is 1 of 5 behavioral states in infancy. According to his observations, fuss-ing is a state of transition. Excessive proportion of fussing and crying may be taken off from either awake or sleep states. The diary-based studies have suggested that excessive fussing or crying is at least partly taken “off” from sleep time and therefore will be reflected also in the development of infants’ sleep-wake rhythm. However, excessive fussing and cry-ing could also be a consequence of sleep deprivation, which may lead to difficulty in behavioral control.

Excessively crying infants may have characteristics that disturb the sleep structure. Cow milk allergy as a distressing factor has been described to cause a disruption of sleep and an increase in the proportion of undetermined NREM sleep in infants.20 Because REM sleep is easily disturbed in infants, a REM sleep disturbance would also be expected.21–23

In this study, we performed an ambulatory 24-hour sleep polygraphy in a home environment in excessively crying and control infants at the age of 6 weeks. The setting was designed to compare parental diary reports and sleep polygraphy during a whole 24-hour sleep-wake cycle and to asses whether ex-cessive crying is associated with changes in sleep structure.

METHODS Study Infants and Study Design

The study infants were recruited to the study by informing all of the parents of newborn infants at the Turku University Hospi-tal. The written information included the following description of “colic”: crying or fussing for 3 hours or more a day on 3 or more days a week in an otherwise healthy and thriving infant. If the symptoms of colic had lasted ⬎1 week and the parents were interested in participating the study, then they were asked to contact the researchers. Control infants were invited to the study through a telephone call interview. The parents of control infants reported that the amount of crying of their infants was in a normal range. The study infants were healthy at the study entry and had an uneventful neonatal history. All parents were interviewed, and infants were examined by a child neurologist at their homes (J.K.). All parents kept a diary for 4 successive days during a study at the age of 6 weeks. In the diary, they recorded whether the infant was awake and content, fussing, crying, feeding, or sleeping. They also recorded their own behavior in respect to the infant: holding the infant, moving the infant around (eg, in a stroller), or taking care of the infant.24The diaries were kept with the accuracy of 5 minutes, but the codes were filled in by parents as convenient. The sleep polygraphy recording was performed during 1 of the diary days. The diary data during sleep polygraphy were not included in the baseline diary data; thus, the diary data were averaged across the 3 days.

The follow-up of the infants was organized as a health ques-tionnaire at the age of 8 months. In the quesques-tionnaire, the follow-ing questions were asked in dichotomous manner (when the an-swer was yes, parents were asked to describe the problem in detail): “Has your child problems falling in sleep?” “Has your child problems in sleeping?” “How many times your child wakes

up during a night?” “Has your child any allergies?” “Has your child eczema?” “Has your child any limitations in diet?” “Please, give the number of antibiotic treatments; the number of otitis media.” “Has your child been diagnosed to have a disease?”

A written consent for the study was obtained from the parents of each infant. The study protocol was approved by the Joint Commission on Ethics of the University of Turku and the Turku University Hospital.

Sleep Polygraphic Recordings

The sleep polygraphic recordings were performed during 1 of the diary days. The preparations for ambulatory sleep polygraphic recording were done at the hospital. After mounting the electrodes at the hospital, the recording was continued at home in the natural environment of the infant. The recording was started daytime (between 9:30amand 4:30 pm) and continued for the next 25 hours. The first 30 minutes to 1 hour at the beginning of the recording were excluded from the analysis to exclude the time needed to return home from the hospital.

The recordings were made with EMBLA sleep recording polygraph and analyzed by Somnologica 3 software (Medcare, Reykjavik, Iceland). The following channels were recorded: 2 elec-troencephalograms (EEGs; C4/A1 and C3/A2), 2 electro-oculo-grams, chin electromyogram (EMG), and an abdominal strain gauge for respiration movements. Two electrocardiogram elec-trodes were placed on the chest area, and 2 electrogastrography electrodes were placed on the abdominal area. Disposable elec-trodes were used (Blue Sensor; Medicotest, Ølstykke, Denmark) on the hairless skin area, and silver cup electrodes were used on the hairy scalp area. The sampling frequency was 100 Hz for all signals, but respiration belt was recorded using 10-Hz data sam-pling.

The 24-hour ambulatory sleep recordings were scored in 30-second epochs. The infant state was scored as REM sleep, light NREM sleep, deep NREM sleep, movement time, or awake. Sleep scoring was based on the criteria published by Guilleminault and Souquet25with some modifications. All sleep states that did not meet the criteria for REM sleep were scored as NREM sleep. The deep NREM sleep was scored when the criteria for scoring stages 3 to 4 were met without the strict amplitude criterion of EEG⬎150

V or whenever EEG showed a trace alternate pattern. All NREM sleep epochs that did not meet the criteria of deep NREM sleep were scored as light NREM sleep. Scoring of awake included also modified criteria, because no observational data were available, ie, direct information about body movements or whether eyes were open or closed. Awake was scored when 1) low-voltage, mixed-frequency EEG was associated with moderate or high chin EMG tone with eye movements ⫾ irregular respiration or 2) in the presence of high EMG tone⫾eye movements⫾movement arti-facts and 3) when 2 or more successive movement time epochs occurred. The epochs of movement time were ignored in the determination of the length of sleep stages and in the number of sleep-stage transitions. The parameters analyzed from the sleep recordings were reported for each quartile of the day. The first incomplete quartile at the beginning of the recording was summed together with the last (corresponding) quartile at the end of the recording.

Statistical Analysis

As a way to report statistical data, the expression mean (stan-dard deviation, range) was used. The estimation of the size of the study groups was based on our previous study.18According to a power analysis, 18 study infants were needed to observe a 10% difference in a whole-day sleep time at the significance level of .05. For statistical analysis, 1-way analysis of variance or analysis of variance for repeated measures was used for the continuous and normally distributed variables and2test for the categorical vari-ables. The SPSS 10.0 for Windows statistical software was used (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS Patients

pro-tein allergy and 1 infant in the control group as a result of technical failure in the power supply during the recording. Finally, 24 infants were included in the group of excessively crying infants, and 23 were included in the control group. The demographic data of the study infants are shown in Table 1.

Diaries

The reported duration of daily fussing and crying was longer and the number of fussing and crying bouts was higher in the group of excessively crying infants than in the control group (Table 1). In the group of excessively crying infants, the duration of fussing and crying exceeded 3 hours in 12 infants during 3 or 4 diary days, in 9 infants during 1 or 2 diary days, and in 3 infants during none of the diary days. In the control group, 3 infants had⬎3 hours of fussing and crying during 1 or 2 days and the rest of group during none of the days.

As shown in Fig 1, the duration of fussing and crying was longer in the group of excessively crying infants than in the control group during all quartiles of the day. The fussing and crying clustered in the evening hours in both groups. Caregivers used a longer time to hold the infant in the group of exces-sively crying infants than in the control group during the day (308 minutes [142; 107–702] compared with 231 minutes (93; 58 – 445);P⫽.03). The time used to move the infant in a stroller or in a car did not differ between the study groups (66 minutes [43; 0 –155] in

the group of excessively crying infants compared with 90 minutes [68; 0 –330] in the control group [P⫽

.25]); neither did the time used for caregiving (69 minutes [26; 30 –138] compared with 66 minutes [24; 25–117;P ⫽.62], respectively).

The reported duration of sleep was shorter in the group of excessively crying infants compared with the control group. According to the diaries, the av-eraged daily sleep time was 808 minutes (63; 675– 943) in the group of excessively crying infants and 869 minutes (110; 630 –1058) in the control group (P

⫽.02). The distribution of the sleep in the quartiles of day is shown in Fig 1. The duration of the nighttime sleep was reported to be shorter in the group of excessively crying infants than in the control group (P ⫽ .002; Fig 1). The differences during the other quartiles of the day were not significant between the study groups. The reported amount of the sleep was highest during the nighttime (midnight to 6am) and reduced steadily the following quartiles of a day in both study groups (P ⫽ .1 for group difference; Fig 1).

The duration of fussing and crying correlated in-versely with the duration of reported sleep time. Within the group of excessively crying infants, the Pearson correlation coefficient was for the whole day (r⫽ ⫺0.34 (P⫽.1) and for quartiles of a day: night-time (midnight to 6am;r⫽ ⫺0.84;P⬍.001), morn-ing (6am to noon; r ⫽ ⫺0.69;P ⬍ .001), afternoon (noon to 6 pm; r ⫽ ⫺0.66; P ⬍ .001), and evening

TABLE 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Mothers and Infants in the Study Groups Excessively Crying Infants

(n⫽24)

Control Infants (n⫽23)

Mothers’ age*, y 31.9 (5.3, 21–43) 29.1 (3.5, 23–36)

Mothers’ education

School educationⱕ9 y 2 5

School educationⱖ9 y, nonacademic 14 15

Academic training (university student or degree) 8 3

Single/married or living with a partner 1/23 0/23

Primiparous/multiparous 9/15 10/13

Infant’s gender, female/male 13/11 11/12

Gestational age, wk 40.0 (1.1, 37.3–42.0) 39.9 (1.1, 37.7–42.0)

Birth weight, g 3439 (408, 2735–4120) 3616 (431, 2520–4260)

Type of delivery

Vaginal 22 21

Cesarean section 2 2

Apgar score

1 min 9 (8–10) 9 (8–10)

5 min 9 (8–10) 9 (8–10)

Diet

Breastfed 13 13

Formula fed 4 —

Mixed 7 10

Weight gain, g

1 mo of age 4330 (519, 3500–5640) 4392 (546, 3710–5200)

2 mo of age 5320 (656, 4350–6660) 5614 (580, 4835–6500)

6 mo of age 7921 (1116, 6300–10 840) 8416 (771, 6940–9960)

Study age, wk 6.3 (1.0, 5.9–6.7) 6.0 (0.6, 5.7–6.3)

Mean fuss time, min/d† 155 (67, 55–307) 62 (39, 0–150)

Mean cry time, min/d† 68 (45, 7–167) 12 (17, 0–72)

Mean fuss and cry time, min/d† 222 (80, 92–383) 74 (48.7, 0–155)

No. of fuss bouts per day† 10.2 (4.5, 1.7–20.0) 5.3 (3.5, 0–13.0)

No. of cry bouts per day† 4.9 (3.3, 0.7–16.7) 1.1 (1.3, 0–4.3)

No. of fuss and cry bouts per day† 15.1 (6.5, 5.3–36.7) 6.4 (4.6, 0–16.0)

Data are mean (standard deviation, range). The median (range) is shown for Apgar scores. The reported cry and fuss parameters are averaged across the 3 nonpolygraphy diary days.

(6 pm to midnight; r ⫽ ⫺0.27; P ⫽ .2). Within the control group, the duration of fussing and crying correlated with sleep during the nighttime (r ⫽

⫺0.50;P⫽ .02) but not other quartiles of day (6am to noon:r⫽ ⫺0.25;P⫽.3; noon to 6pm:r⫽ ⫺0.15;

P⫽ .5; 6pm to midnight:r ⫽ ⫺0.23;P ⫽ .3) or the whole day (r⫽0.09;P⫽ .7).

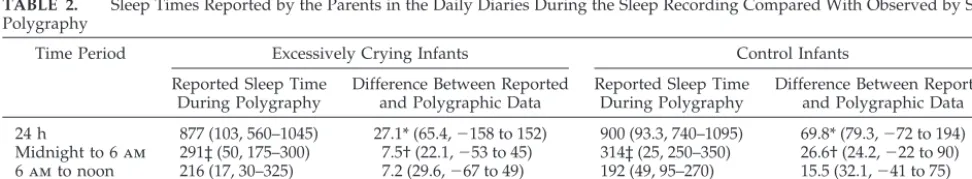

The diary data of the 24-hour polygraphy period showed shorter nighttime sleep in the group of ex-cessively crying infants compared with the control subjects (Table 2), but the total reported duration of sleep did not differ between the study groups during the recording hours (P⫽.3). The reported amount of fussing and crying during the sleep polygraphy was 202 minutes (73; 110 –395) in the group of excessively crying infants and 76 minutes (54; 0 –170) in the control group (P ⬍ .001). The reported amount of holding or carrying did not differ between the study groups during the recording hours (276 minutes [165; 15–595] in the group of excessively crying in-fants compared with 201 minutes [116; 40 –545] in the

control group; P ⫽ .08). The reported amounts of sleep (r⫽0.61), fussing and crying (r⫽0.89), carry-ing (r⫽0.84), moving (r⫽0.59), and caregiving (r⫽

0.63, P ⬍ .001 for all) correlated with the averaged 3-day diary data. The reported amount of sleep was higher during the polygraphy recording than during the 3-day diary period (P⬍ .001), and the reported amounts of carrying and caregiving were lower (31 minutes [81;⫺136 to 263) for carrying [P⫽.01] and 18.5 minutes [21;⫺30 to 77) for caregiving [P⫽.001]) in both study groups. No group differences were found (P⫽ .1,P⫽.9, and P⫽.6, respectively).

Sleep Polygraphy

No difference between the study groups was found in the total duration of sleep in the 24-hour sleep recording. When the structure of total sleep was analyzed, there were no differences in the pro-portions of sleep stages between the groups (Table 3).

The duration and structure of sleep during the quartiles of a day are shown in Fig 2. The only significant difference in the duration was longer sleep time during the morning hours (6amto noon) in the group of excessively crying infants compared with the control group (Fig 2). When the sleep struc-ture was analyzed separately according to the quar-tiles of day, the proportion of REM sleep was found to be greater during nighttime (midnight to 6am) in the group of excessively crying infants compared with the control subjects (Fig 2). The proportion of REM sleep during nighttime was 31.2% (7.5; 17.5– 47.4) in the group of excessively crying infants com-pared with 26.0% (5.8; 17.9 –36.2) in the control group (P ⫽ .01). The mean length of uninterrupted REM periods was also longer in the group of excessively crying infants than in the control group during the nighttime (4.4 minutes [1.0; 2.6 – 6.0] compared with 3.7 minutes [0.9; 2.0 –5.0];P ⫽ .01). However, when REM period was determined so that it included a 1-minute interruption instead of 30-second epoch by another sleep stage, no differences were found be-tween the study groups (P⫽.2). All other differences between sleep parameters were insignificant.

The parental reports of sleep were overestimations compared with sleep polygraphic observations. For all study infants, the difference in the total 24-hour sleep time was 48.0 minutes (74.9;⫺158 to 193;P⬍

Fig 1. Distribution of infant behaviors reported in daily diaries is shown in the quartiles of day.䊐, nighttime (midnight to 6am);o, morning hours (6amto noon);s, afternoon (noon to 6 pm);■, evening hours (6pmto midnight). On the left side, the combined duration of crying and fussing was higher in the group of exces-sively crying infants than in the control group during all quartiles of the day (Pⱕ.001). In both groups, the highest amount of crying and fussing occurred during the evening hours (6pmto midnight). On the right side, the duration of reported sleep was shorter during the nighttime in the group of excessively crying infants compared with the control group (P⫽.008). Sleep times did not differ between the study groups during any other quartiles of the day.

TABLE 2. Sleep Times Reported by the Parents in the Daily Diaries During the Sleep Recording Compared With Observed by Sleep Polygraphy

Time Period Excessively Crying Infants Control Infants

Reported Sleep Time During Polygraphy

Difference Between Reported and Polygraphic Data

Reported Sleep Time During Polygraphy

Difference Between Reported and Polygraphic Data

24 h 877 (103, 560–1045) 27.1* (65.4,⫺158 to 152) 900 (93.3, 740–1095) 69.8* (79.3,⫺72 to 194) Midnight to 6am 291‡ (50, 175–300) 7.5† (22.1,⫺53 to 45) 314‡ (25, 250–350) 26.6† (24.2,⫺22 to 90) 6amto noon 216 (17, 30–325) 7.2 (29.6,⫺67 to 49) 192 (49, 95–270) 15.5 (32.1,⫺41 to 75) Noon to 6pm 199 (59, 110–305) 10.9 (24.0,⫺36 to 64) 227 (66, 85–330) 22.6 (31.5,⫺31 to 78) 6pmto midnight 171 (171, 30–280) 1.4 (24.9,⫺36 to 47) 168 (63, 30–280) 5.2 (36.5,⫺74 to 88)

The sleep times reported by parents during recordings were subtracted from the sleep times observed in sleep polygraphy. Data are (standard deviation, range) in minutes.

.001), 16.9 minutes (24.8;⫺53 to 90;P⬍.001) during nighttime, 16.6 minutes (28.2; ⫺67 to 75; P ⬍ .001) during daytime, 11.3 minutes (30.8;⫺74 to 88;P ⬍

.05) during morning hours, and 3.3 minutes (30.9;

⫺74 to 88;P⫽.7) during evening hours. There was a group difference such that the parents in the con-trol group overestimated the sleep time significantly more compared with the group of excessively crying infants (Table 2).

Individual variation occurs between infants in the circadian sleep-wake periodicity. That is why a rigid division of a day into 4 quartiles may hide group differences. We analyzed also the proportions of sleep stages using the longest sleep period in the evening as a starting point. The study infants usually had a long sleep period after a long evening waking period typical for their age. This procedure allowed

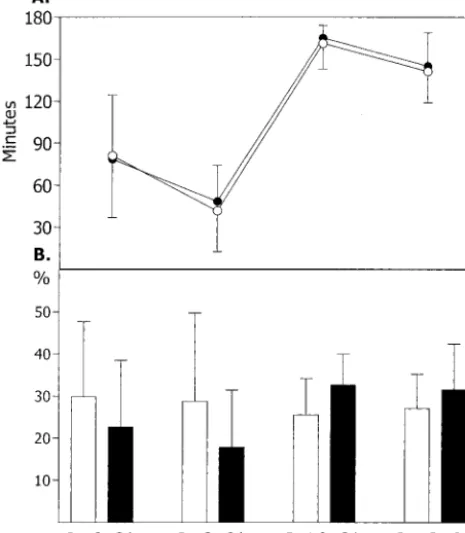

comparison of the infants “in the same physiologic circadian rhythm.” The beginning of the long sleep period was at 10:42pm(1:51; 8:06pm– 4:02am) in the group of excessively crying infants and at 10:37 pm (1:29; 7:26pm–1:50am) in the control group (P⫽.8). The reported duration for fussing and crying during the 3-hour period before a long sleep period was 54 minutes (28; 10 –110; 40% [19; 8 –73] from awake time) in the group of excessively crying infants and 25 minutes (27; 0 –90; 20% [20; 0 – 60] from awake time) in the control group (P ⫽ .001). The 2 subse-quent 3-hour periods before and after the starting point were analyzed. The observed duration of sleep did not differ between the study groups in any of these 3-hour periods in polygraphic recordings (Fig 3A). The reported amount of fussing and crying cor-related negatively to the observed amount of sleep in polygraphy in the group of excessively crying infants during the 3-hour period before a long sleep (Pear-son correlation: ⫺0.52 [P ⫽ .01] for the group of excessively crying infants and⫺0.25 [P⫽.2] for the control group). However, no such a correlation was found when total 24-hour observed sleep was com-pared with fussing and crying (P⫽ .6).

There was a significant group difference in a sleep structure such that during the periods preceding the long sleep period, the proportion of REM sleep was lower in the group of excessively crying infants and during a long sleep period the proportion of REM sleep was higher in the group of excessively crying infants compared with control subjects (P⫽.001; Fig 3B). The proportion of light NREM sleep differed between 3-hour periods (P ⫽ .01) but not between the study groups (P ⫽ .4). The proportion of deep NREM sleep did not differ between 3-hour periods (P⫽.08) or between the study groups (P⫽.1). When the 3-hour periods were analyzed separately, the excessively crying infants showed more deep NREM sleep than control infants during the 3-hour period before a long sleep (39.0% [15.4; 0 – 84.4] compared with 27.8% [21.3, 0 – 61.7], respectively [P⫽.05]), and the excessively crying infants showed less light NREM sleep than control subjects during the first 3-hour period of long sleep (27.7% [8.3; 11.6 – 43.9] compared with 35.4% [9.7; 16.6 –51.4];P⫽.005). No

Fig 2. The circadian distribution of the observed sleep times and the proportions of different sleep stages are shown. The bars represent the total sleep time in minutes. The sections of bars represent the durations of different sleep stages:■, REM sleep stage;o, light-NREM sleep stage;䊐, deep NREM sleep stage;s, movement time. Standard deviation of total sleep time is illus-trated by an upward line on the top of the bar, standard deviations of the NREM sleep stage durations are illustrated by downward lines, and REM sleep is illustrated by upward lines. Total sleep time was longer in the group of excessively crying infants than in the control group in the morning (6amto noon;P ⫽.03). The proportion of REM sleep stage was greater in the group of exces-sively crying infants than in the control group during the night-time (P⫽ .01). All other differences between the study groups were insignificant.

TABLE 3. The 24-Hour Sleep Polygraphic Data in the Study Groups

Excessively Crying Infants Control Infants

Total sleep time, min 850.2 (79.8, 718.0–991.5) 830.2 (74.8, 669.0–1002.5) Proportion of sleep stages from sleep

time, %

REM sleep 29.4 (6.5, 14.8–42.5) 27.4 (5.8, 17.4–38.0)

Light NREM sleep 31.6 (6.2, 17.7–41.8) 34.5 (5.6, 26.5–43.8) Deep NREM sleep 36.7 (3.9, 31.1–44.6) 35.9 (3.6, 30.1–43.1)

Movement time 2.3 (0.7, 1.2–3.9) 2.2 (0.6, 1.2–3.6)

No. of sleep-stage transitions per hour of sleep time

9.8 (1.7, 6.6–13.0) 10.0 (1.9, 7.1–14.2)

No. of REM periods 66.6 (19.1, 35.0–102.0) 66.6 (18.9, 38.0–106.0) Length of REM periods, min 4.0* (0.7, 2.5–5.2) 3.6* (0.5, 2.7–4.4) No. of light NREM sleep periods 93.3 (17.0, 65.0–125.0) 92.4 (17.9, 69.0–132.0) Length of light NREM sleep periods, min 3.1 (0.8, 1.5–4.2) 3.3 (0.9, 2.1–5.2) No. of deep NREM sleep periods 19.9 (3.5, 15.0–28.0) 19.0 (3.4, 13.0–29.0) Length of deep NREM sleep periods, min 16.0 (2.9, 10.9–23.3) 16.0 (2.3, 8.9–18.9)

differences between the study groups were observed in the number of REM periods (P⫽.1), the length of REM periods (P⫽ .4), or the number of sleep-stage transitions (P⫽ .5).

The temporal relation between diaries and sleep polygraphy was evaluated by comparing the begin-ning of the long sleep period. The time difference between these 2 methods for all infants was 8 min-utes (25;⫺65 to 182), and there was no group differ-ence (P ⫽.6).

Follow-up Questionnaire

To follow the general health of the studied infants, we sent a questionnaire to the parents after 6 months of age. The questionnaire was returned by the par-ents of 20 excessively crying infants and 22 control infants. The mean age of infants at the time of the questionnaire was 8.7 months (1.5; 6.4 –12.6) in the group of excessively crying infants and 8.6 months (1.9; 6.1–12.7) in the control group (P ⫽ .9). No dif-ferences were found in suspected (by the parents or physician) or diagnosed illnesses (Table 4). One ex-cessively crying infant had received cisapride medi-cation for clinical suspicion (without pH recording) of gastroesophageal reflux after the study.

The parents in the group of excessively crying

infants reported more problems in falling asleep than in the control group (Table 4). There was a trend toward more perceived sleeping problems in the group of excessively crying infants (P ⫽ .09). The number of awakenings during nighttime was similar between the study groups.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shown that 24-hour sleep in the excessively crying and control infants was similar in the amount and structure in the sleep polygraphy recordings. The contradictory finding in parental di-ary recordings was explained by the bias as the par-ents of control infants overestimated the amount of sleep in their infants more than the parents of exces-sively crying infants. Also, parents in both study groups reported more sleep in the diaries than was observed using polygraphic home recordings. Exces-sively crying infants had a relative REM sleep defi-ciency during the evening hours followed by REM sleep rebound during the following long sleep pe-riod, although no major group differences in the total sleep structure of a 24-hour day were found.

Parental perception of crying was used to deter-mine the groups of colicky and control infants, cause parents may reach characteristics of infant be-havior that are not quantifiable by using simple measurement of crying amounts by diaries.26,27 Pa-rental perception correlated well with the amount of fussing and crying according to the diary records, and only a little overlapping occurred in the amount of fussing and crying between the groups. According to follow-up questionnaires, the excessively crying infants did not differ from the control subjects in the amount of atopic illnesses or the amount of received antibiotic therapies. The reported amount of sleep was higher during the polygraph recordings than the averaged 3-day diaries (P ⬍ .001; text and Table 2), suggesting that the polygraphy recordings did not disturb the sleep of infants. However, fewer parental activities with their infants (holding and caregiving) were reported during polygraphic recording hours, suggesting that recordings affected infant–parent

in-Fig 3. The total sleep time and the proportion of REM sleep stages before and after the beginning of a long sleep period during the evening are shown. The beginning of the long sleep period was determined individually for each study infant, and the 2 subse-quent 3-hour periods before and after the beginning time were analyzed. A, Total sleep times during 3-hour periods did not differ between study groups.F, excessively crying infants (standard error is shown as upward error bars);E, control infants (standard error is shown as downward error bars). B, Proportions of REM sleep stage during 3-hour time periods. ■, excessively crying infants;䊐, control infants.P⫽.002 for differences in REM sleep proportion between study groups (analysis of variance for re-peated measures).

TABLE 4. Questionnaire at the Age of 8 Months Excessively Crying Infants

(n⫽20)

Control Infants (n⫽22)

Problems in falling asleep 8 (40%) 2 (9%)* Problems in maintaining sleep 7 (35%) 3 (14%) No. of night wakings

0–1 9 (45%) 11 (50%)

2–4 6 (30%) 8 (36%)

⬎4 4 (20%) 3 (14%)

Problems in feeding 5 (25%) 2 (9%)

Suspicion or proven food allergy 2 (10%) 2 (9%) No. of antibiotic therapies

0 13 (65%) 18 (82%)

1–2 6 (30%) 3 (14%)

⬎2 1 (5%) 1 (5%)

No. of otitis media

0 13 (65%) 15 (18%)

1 6 (30%) 5 (23%)

⬎2 1 (5%) 2 (9%)

teraction, which may be reflected as increased sleep of their infant. No difference was observed in the total reported amount of sleep between the study groups during the polygraphic recordings, which may be attributable to the day-to-day variability of the amount of sleep and too low power of the study to find a difference in 1-day data.

The diary data suggesting less sleep in excessively crying infants is consistent with previous studies based on parental reports.15,16,18A negative correla-tion between parental reports of the amount of sleep and fussing and crying also was found earlier.16 However, polygraphic recordings suggest that the total duration of daily sleep was not affected by excessive fussing and crying. This finding is consis-tent with our earlier sleep laboratory study.18 Com-pared with our first study,18 the strengths of this study had some advantages. The recordings were performed in infants’ natural home environment and lasted throughout a whole 24-hour sleep-wake cycle. Our second finding was that parental reports over-estimated infant sleep more in the control group than in the group of excessively crying infants. The pre-vious results suggesting shorter sleep in excessively crying infants were based on parental reports that, according to this study, may be biased by parents’ tendency to report more sleep than actually occurs. It is likely that parents miss quiet periods of wakeful-ness. It is logical that waking periods are easily missed in infants who do not fuss or cry when awake. It has been shown that 3-month-old infants who cry at night receive more interventions by moth-ers and are removed from the crib when awake more often than the self-soothers who do not cry and receive maternal intervention when awake.28

With this study setting, the observational compo-nent was not included in the scoring of sleep-wake states; therefore, we were not aware of whether eyes were open or closed and did not differentiate short manipulation periods by caregivers from active wake periods during polygraphy recordings. This may have caused some inaccuracy in the comparison between diary and polygraphic data. We have com-pared a behavioral scoring method (parental diaries) with a polygraphic method in assessing infants’ be-havioral states instead of comparing parental report-ing with another objective behavioral scorreport-ing method such as video recording. Sleep polygraphy has been used as a gold standard to determinate the behavioral states, although there could be inconsis-tency between polygraphic signals and sleep states in 6-week-old infants. In our scoring system, we relied on appearance of eye movements and chin EMG activity and basal tone in distinguishing be-tween quiet awake and light NREM sleep and also between REM sleep stage and awake. It has been shown that there may be a lack of concordance be-tween EMG tone and other sleep polygraphic signals in infants younger than 3 months. This may be at-tributable to immaturity of infants’ physiology or may reflect ambiguity in scoring infants’ states gen-erally.29 Because of these characteristics of infant sleep, it is possible that some quiet awake states (behaviorally eyes open) were scored as sleep (light

NREM) in the present study; therefore, overestima-tion of the amount of sleep compared with behav-ioral method can be possible in the sleep recordings. This kind of error would only strengthen our results as we already scored less sleep compared with the reported diary data. However, eye movements would be expected when eyes are open. Similarly, awakenings as a result of carrying or manipulation of the infants cannot be differentiated from the spon-taneous awakenings. The study groups did not differ in carrying time during the polygraphic recordings, although the difference was found in 3-day diary data. The observed overall sleep time as well as total REM and NREM proportions were similar to what was described by Guilleminault and Coons6in their 24-hour sleep polygraphy study of 10 infants at the age of 6 weeks in a sleep laboratory. Also, the results were similar to our earlier sleep polygraphy study in which the behavioral observation (video recording) was included in sleep-stage scoring.18

Because there was no other evidence for REM sleep disruption than decreased proportion of REM sleep, it is also possible that this was attributable to an increase of NREM proportion of sleep. During the 3-hour period preceding the long sleep, excessively crying infants showed more deep NREM sleep than control subjects. During that 3-hour period, exces-sively crying infants slept⬃27% of time, and fussing and crying occurred⬃40% of wake time. Thus, the sleep during that time period was associated with a stressful awake time. It has been described in 4-month-old infants that allergy to cow milk can cause a disturbance of sleep structure, frequent awakenings, and an increase in the proportion of undetermined NREM sleep.20 Sleep deprivation, which was not supported in our study in excessively crying infants, has been described to cause a similar type of change by increasing both S4 and REM sleep stages in adults.30

An association between REM sleep and crying spells has been proposed by Weissbluth,31especially during fussy REM state defined by Emde and Met-calf32 in which the infant is fussing according to behavioral criteria but is in REM sleep according to polygraphic criteria. In this study, the recording of infant fussing and crying was based on parental reports, and accuracy of time matching between di-ary reports and sleep recordings was too low to allow direct comparison between cry onset and in-fant state.

The finding that there was no difference in the beginning time of the long evening sleep period be-tween the study groups suggests that the diurnal sleep-wake cycle did not differ between the study groups. However, both observed and reported sleep time during polygraphy was longer during morning hours in excessively crying infants than in control subjects, which suggest a short sleep-wake cycle shift. This may be attributable to the recording pro-cedure as there was a difference only during polyg-raphy (Fig 2) but not in the averaged 3-day data (Fig 1). Because one third of the sleep recordings were started during morning hours, that quartile of day is a mixture of 2-day data and therefore the data are less clear.

The length of uninterrupted REM sleep was longer in the group of excessively crying infants than in the control group. It may be concluded that the exces-sively crying infants had fewer short (30 seconds) interruptions of REM sleep, because no difference in the length of REM periods between the study groups was observed when 1-minute interruptions were al-lowed in the middle of REM periods. In our previous sleep laboratory study, we found a tendency that infants with colic had a fewer number of movements during sleep. The results of this study suggest that sleep of excessively crying infants may be more con-solidated during nighttime and morning hours than in control subjects.

The parents of excessively crying infants perceived that their infants had more problems in falling asleep at 8 months of age than the parents of control infants. However, the number of night waking was not dif-ferent between study groups. This is consistent with

earlier findings. Despite a lack of evidence of objec-tive differences in later child behavior in colicky infants, parental perception of child behavior is dif-ferent.5,12–14

In conclusion, this study, together with our earlier study, shows that the duration of sleep and the over-all structure of sleep are similar between normal and excessively crying infants at the time when crying amounts are shown to peak during early infancy. These results suggest that crying time does not re-duce the sleeping time. That most of the crying is clustered in the evening hours may reflect normal maturing of the sleep-wake rhythm with the wake-fulness occurring in late afternoon or evening.7,33 However, the present study suggests that excessively crying infants may have characteristics that lead to a relative REM sleep deficiency during evening hours, at the time when the most crying and fussing occurs. Later in night, a REM sleep rebound was observed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported financially by the South-West Finn-ish Fund of Neonatal Research, the Turku University Foundation, and the Turku University Hospital.

We thank Helena Haapanen for informing parents of newborn infants about the study. We also thank the parents and infants who participated in this study.

REFERENCES

1. Barr RG, Konner M, Bakeman R, Adamson L. Crying in !Kung San infants: a test of the cultural specificity hypothesis.Dev Med Child Neurol.1991;33:601– 610

2. Barr RG, Chen S, Hopkins B, Westra T. Crying patterns in preterm infants.Dev Med Child Neurol.1996;38:345–355

3. James-Roberts I, Halil T. Infant crying patterns in the first year: normal community and clinical findings. J Child Psychol Psychiatry.1991;32: 951–968

4. Wessel M, Cobb JC, Jackson EB, Harris GS, Detwiler AC. Paroxysmal fussing in infancy, sometimes called “colic.”Pediatrics.1954;14:421– 434 5. Lehtonen L, Gormally S, Barr RG. Clinical pies for etiology and outcome in infants presenting with early increased crying. In: Barr RG, Hopkins B, Green JA, eds.Crying as a Sign, a Symptom, and a Signal. London, United Kingdom: Mac Keith Press; 2000:169 –178

6. Coons S, Guilleminault C. Development of sleep-wake patterns and non-rapid eye movement sleep stages during the first six months of life in normal infants.Pediatrics.1982;69:793–798

7. Giganti F, Fagioli I, Ficca G, Salzarulo P. Polygraphic investigation of 24-h waking distribution in infants.Physiol Behav.2001;73:621– 624 8. Coons S, Guilleminault C. Development of consolidated sleep and

wakeful periods in relation to the day/night cycle in infancy.Dev Med Child Neurol.1984;26:169 –176

9. Hoppenbrouwers T, Hodgman JE, Harper RM, Sterman MB. Temporal distribution of sleep states, somatic activity, and autonomic activity during the first half year of life.Sleep.1982;5:131–144

10. Weissbluth M, Davis AT, Poncher J. Night waking in 4- to 8-month-old infants.J Pediatr.1984;104:477– 480

11. Stahlberg MR. Infantile colic: occurrence and risk factors.Eur J Pediatr.

1984;143:108 –111

12. Rautava P, Lehtonen L, Helenius H, Sillanpaa M. Infantile colic: child and family three years later.Pediatrics.1995;96(suppl):43– 47 13. Lehtonen L, Korhonen T, Korvenranta H. Temperament and sleeping

patterns in colicky infants during the first year of life. J Dev Behav Pediatr.1994;15:416 – 420

14. Canivet C, Jakobsson I, Hagander B. Infantile colic. Follow-up at four years of age: still more “emotional.”Acta Paediatr.2000;89:13–17 15. James-Roberts IS, Conroy S, Hurry J. Links between infant crying and

sleep-waking at six weeks of age.Early Hum Dev.1997;48:143–152 16. White BP, Gunnar MR, Larson MC, Donzella B, Barr RG. Behavioral and

physiological responsivity, sleep, and patterns of daily cortisol produc-tion in infants with and without colic.Child Dev.2000;71:862– 877 17. Papousek M, vonHofacker N. Persistent crying and parenting: search

Kero P. Infants with colic have a normal sleep structure at 2 and 7 months of age.J Pediatr.2001;138:218 –223

19. Wolff PH.The Development of Behavioral States and the Expression of Emotions in Early Infancy: New Proposals for Investigation. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1987

20. Kahn A, Francois G, Sottiaux M, et al. Sleep characteristics in milk-intolerant infants.Sleep.1988;11:291–297

21. Shapiro CM, Devins GM, Hussain MR. ABC of sleep disorders. Sleep problems in patients with medical illness.BMJ.1993;306:1532–1535 22. Harrington C, Kirjavainen T, Teng A, Sullivan CE. Cardiovascular

responses to three simple, provocative tests of autonomic activity in sleeping infants.J Appl Physiol.2001;91:561–568

23. McNamara F, Sullivan CE. Sleep-disordered breathing and its effects on sleep in infants.Sleep.1996;19:4 –12

24. Barr RG, Kramer MS, Boisjoly C, McVey-White L, Pless IB. Parental diary of infant cry and fuss behaviour.Arch Dis Child.1988;63:380 –387 25. Guilleminault C, Souquet M. Scoring criteria. In: Guilleminault C, ed.

Sleeping and Waking Problems: Indications and Techniques. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co; 1982:415– 426

26. Lester BM, Boukydis Z, Garcia-Coll CT, Hole WT. Colic for develop-mentalists.Inf Ment Health J.1990;11:321–333

27. Zeskind PS, Barr RG. Acoustic characteristics of naturally occurring cries of infants with “colic.”Child Dev.1997;68:394 – 403

28. Anders TF, Halpern LF, Hua J. Sleeping through the night: a develop-mental perspective.Pediatrics.1992;90:554 –560

29. Hoppenbrouwers T. Polysomnography in newborns and young infants: sleep architecture.J Clin Neurophysiol.1992;9:32– 47

30. Webb WB, Agnew HW Jr. The effects of a chronic limitation of sleep length.Psychophysiology.1974;11:265–274

31. Weissbluth M. Sleep and the colicky infant. In: Guilleminault C, ed.

Sleep and Its Disorders in Children. New York, NY: Raven Press; 1987: 129 –140

32. Emde RN, Metcalf DR. An electroencephalographic study of behavioral rapid eye movement states in the human newborn.J Nerv Ment Dis.

1970;150:376 –386

33. Bamford FN, Bannister RP, Benjamin CM, Hillier VF, Ward BS, Moore WM. Sleep in the first year of life.Dev Med Child Neurol.1990;32:718 –724

STUDY FAULTS COLLEGES ON GRADUATION RATES

“As growing numbers of Americans enter college, most colleges and universities have failed to ensure that those students will graduate, according to a study released yesterday by the Education Trust in Washington. Only 63 percent of full-time college students at four-year colleges graduate within six years—a com-mon yardstick for measuring graduation rates—the report said, and those rates have basically remained flat for 30 years. Graduation rates are especially low for minority students and those from low-income families, the trust said. Only 46 percent of black students, 47 percent of Latino students, and 54 percent of low-income students graduate within six years. ‘The typical American college or university has a graduation rate gap between white and African-American stu-dents of over 10 percentage points,’ the report said, and a quarter of the institutions have a gap of 20 points or more. The pattern for Hispanic students is similar, it said.”

Arenson KW.New York Times. May 27, 2004

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2003-0651-L

2004;114;592

Pediatrics

Jarkko Kirjavainen, Liisa Lehtonen, Turkka Kirjavainen and Pentti Kero

Study

Sleep of Excessively Crying Infants: A 24-Hour Ambulatory Sleep Polygraphy

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/114/3/592 including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/114/3/592#BIBL This article cites 29 articles, 5 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/fetus:newborn_infant_ Fetus/Newborn Infant

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2003-0651-L

2004;114;592

Pediatrics

Jarkko Kirjavainen, Liisa Lehtonen, Turkka Kirjavainen and Pentti Kero

Study

Sleep of Excessively Crying Infants: A 24-Hour Ambulatory Sleep Polygraphy

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/114/3/592

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.