Children

’

s Mental Health Emergency

Department Visits: 2007

–

2016

Charmaine B. Lo, PhD, MPH,aJeffrey A. Bridge, PhD,b,c,dJunxin Shi, MD, PhD,e,fLorah Ludwig, BS,gRachel M. Stanley, MD, MHSAa,c

abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:Emergency department (ED) visits for children seeking mental health care have increased. Few studies have examined national patterns and characteristics of EDs that these children present to. In data from the National Pediatric Readiness Project, it is reported that less than half of EDs are prepared to treat children. Our objective is to describe the trends in pediatric mental health visits to US EDs, with a focus on low-volume,

nonmetropolitan EDs, which have been shown to be less prepared to provide pediatric emergency care.

METHODS:Using 2007 to 2016 Nationwide Emergency Department Sample databases, we assessed the number of ED visits made by children (5–17 years) with a mental health disorder using descriptive statistics. ED characteristics included pediatric volume, children’s ED classification, and location.

RESULTS:Pediatric ED visits have been stable; however, visits for deliberate self-harm increased 329%, and visits for all mental health disorders rose 60%. Visits for children with a substance use disorder rose 159%, whereas alcohol-related disorders fell 39%. These increased visits occurred among EDs of all pediatric volumes, regardless of children’s ED classification. Visits to low-pediatric-volume and nonmetropolitan areas rose 53% and 41%, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS:Although the total number of pediatric ED visits has remained stable, visits among children with mental health disorders have risen, particularly among youth presenting for deliberate self-harm and substance abuse. The majority of these visits occur at nonchildren’s EDs in both metropolitan and nonurban settings, which have been shown to be less prepared to provide higher-level pediatric emergency care.

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT:Emergency department visits for children with mental health disorders have risen, but little is known about the types of emergency departments and the rates of mental health disorders that these children present with for emergency mental health care.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS:US children presenting with mental health disorders, particularly deliberate self-harm and substance use disorders, often seek care at facilities that are likely less prepared to provide higher-level pediatric emergency care.

To cite:Lo CB, Bridge JA, Shi J, et al. Children’s Mental Health Emergency Department Visits: 2007–2016.Pediatrics. 2020; 145(6):e20191536

aDivision of Emergency Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio;bCenters for Suicide Prevention

and Research,ePediatric Trauma Research, andfInjury Research and Policy, The Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio;cDepartments of Pediatrics,dPsychiatry, and Behavioral Health, College of Medicine, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio; andgEmergency Medical Services for Children, Division of Child, Adolescent, and Family Health, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, Rockville, Maryland

Drs Lo and Stanley conceptualized and designed the study, conducted the literature review, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised thefinal manuscript; Dr Shi assisted with the study design, performed the data analysis, and critically reviewed and revised thefinal manuscript; Dr Bridge contributed to the study design, provided research methodology guidance, and critically reviewed and revised thefinal manuscript; Ms Ludwig assisted with the literature review and critically reviewed and revised thefinal manuscript; and all authors have approved thefinal manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-1536

Accepted for publication Mar 5, 2020

One infive children in the United States experiences a mental health disorder.1Emergency departments (EDs) often serve as the safety net for children seeking mental health care.2,3There are more ED visits for children with mental health disorders, with hospitalizations for suicide ideation and suicide attempts more than doubling over the last 10 years.4,5

Children with mental health disorders make up∼2% to 5% of all pediatric ED visits nationally, and this number is increasing.6These children are evaluated in all settings ranging from children’s hospital EDs to EDs that see,500 children per year.7,8Most children seeking emergency care are seen in nonchildren’s hospital EDs.9

Although the escalation of ED use for children with mental health disorders has been documented in the

literature, there have been few studies focused on characteristics of the EDs in which these children seek care.10–14The National Pediatric Readiness Project (NPRP), a collaborative effort between the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) Emergency Medical Services for Children program, American Academy of Pediatrics, Emergency Nurses Association, and American College of Emergency Physicians, is a quality improvement initiative that aims to ensure that all US EDs have the essential guidelines and resources in place to provide effective emergency care to children.11,12In data from the NPRP’s Pediatric Readiness Survey, it was reported that less than half of hospital EDs are prepared with policies for children with mental health disorders, and in rural areas, this drops to one-third.8Recently, the NPRP has shown that EDs that see small numbers of children are less likely to be prepared to treat children and have worse outcomes, including mortality.9,15,16

We studied the 10-year trends in pediatric mental health visits in US EDs based on ED characteristics defined from the Pediatric Readiness Survey. Examining the characteristics of EDs that children present to is important because pediatric readiness has been linked to the pediatric volume and geographic location of EDs.

METHODS

We used data from the 2007 to 2016 Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.17NEDS tracks information about ED visits across the country and includes geographic, hospital, and patient information. NEDS is the largest all-payer ED database publicly available in the United States and contains information for∼20% of US EDs.18NEDS is a stratified sample of US hospital-owned EDs, which is representative of all US EDs because the sampling frame takes into account important hospital characteristics, such as geographic region, trauma center level, urban or rural location, teaching status, and hospital.17 We analyzed NEDS by looking at patient demographics, mental health conditions, and hospital ED characteristics.

Patient Demographics

Patient demographic information, such as sex, age, and ED disposition, was examined. We restricted the sample to children ages 5 to 17 years because age of onset for most mental health conditions typically does not occur before age 5.19Age was then categorized into tertiles: 5 to 9, 10 to 14, and 15 to 17 years. We then grouped children into 3 groups: (1) children with any mental health disorders, (2) children with substance use disorders, and (3) children who presented for deliberate self-harm.

Mental Health Conditions Case Definition

We identified any diagnosis of a mental and/or behavioral health disorder and aligned with the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Clinical Classification Software (CCS) groupings for mental and behavioral health disorders.20 CCS is a tool developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality that clustersInternational Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision(ICD-9) andInternational Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision(ICD-10) diagnosis and procedure codes into a clinically meaningful categorization and standard coding system.20–22The categories of any mental health disorders included adjustment disorders (650); anxiety disorder (651); attention-deficit, conduct, and disruptive behavior disorders (652); impulse control disorders (656); mood disorders (657); schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (659); and a miscellaneous mental health disorder group that was inclusive of CCS categories 653, 654, 655, and 670. Substance use disorders included alcohol-related disorders (660) and substance-related disorders (661). Thefinal group of deliberate self-harm was composed of the CCS category suicide and intentional self-inflicted injury (662). The CCS categories and corresponding International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical ModificationandInternational Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification codes are provided in Supplemental Table 2.

Hospital ED Characteristics

(10 000–24 999), very high (25 000–49 999), and extremely high ($50 000). Identification of children’s hospital EDs was

determined by taking the median age of all patients treated in a specific ED. A distinctive bimodal distribution was detected in which children’s hospital EDs had a median age of 10 years or less, whereas nonchildren’s hospital EDs had a median age of.20. NEDS has ED

urban-rural location split into a 4-category designation on the basis of the US Office of Management and Budget metropolitan and micropolitan statistical area standards. These categories are as follows: large metropolitan areas with at least 1 million residents, small metropolitan areas with,1 million residents, micropolitan areas, and not metropolitan or micropolitan (the last is essentially a nonurban

residual). Metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas are standards defined as having a core area containing a substantial population nucleus and close economic and social ties to nearby communities.23

Statistical Analyses

Survey weighted data analytic methods were used to calculate national estimates for each year.

TABLE 1Patient and Hospital Characteristics of ED Visits by Children With a Mental Health Disorder, 2007 vs 2016

Rate, per 1000 Population

2007 95% CI 2016 95% CI % Change P

Age, y

5–9 6.9 6–7.8 10.3 9.1–11.5 49.0 ,.001

10–14 14.5 13–15.9 23.7 21.4–26.1 63.8 ,.001

15–17 31.2 28.9–33.5 52.4 48.8–56.0 67.9 ,.001

Sex

Male 16.9 15.4–18.5 24.5 22.4–26.6 44.9 ,.001

Female 14.7 13.5–15.9 26.3 24.1–28.5 78.7 ,.001

All pediatric ED visits 273.5 249.6–297.5 305.5 272.1–338.8 11.7 .06 Mental health disorders

Total 15.9 14.5–17.2 25.4 23.3–27.5 60.2 ,.001

Any mental disorder 14.0 12.6–15.3 21.0 19.0–22.9 50.3 ,.001

650: adjustment disorders 0.7 0.6–0.9 1.0 0.9–1.2 41.7 .002

651: anxiety disorders 2.8 2.5–3 6.0 5.4–6.7 116.6 ,.001

652: attention-deficit conduct and disruptive behavior disorders 5.8 5.1–6.5 8.1 7.2–9.0 40.1 ,.001 656: impulse control disorders NEC 0.2 0.2–0.3 0.5 0.4–0.6 111.3 ,.001

657: mood disorders 5.2 4.6–5.7 7.4 6.7–8.2 44.0 ,.001

659: schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders 0.4 0.4–0.5 0.4 0.4–0.5 24.6 .27 Miscellaneous mental health disordersb 2.6 2.3–2.9 4.9 4.3–5.5 90.9 ,.001

Substance use disorder 2.6 2.4–2.8 4.6 4.3–4.9 75.4 ,.001

660: alcohol-related disorders 1.4 1.3–1.5 0.9 0.8–0.9 238.6 ,.001 661: substance-related disorders 1.5 1.4–1.7 4.0 3.7–4.2 159.4 ,.001

662: deliberate self-harm 1.1 0.9–1.2 4.6 4.0–5.2 329.3 ,.001

ED disposition

ED visit in which the patient is treated and released 12.5 11.5–13.6 21.3 19.7–22.9 70.0 ,.001 ED visit in which the patient is admitted to this same hospital 2.4 2.0–2.9 3.1 2.5–3.7 26.6 .05 ED visit in which the patient is transferred to another short-term hospital 0.4 0.4–0.4 0.9 0.8–1.1 134.3 ,.001 ED visit in which the patient died in the ED 0.0 0.0–0.0 0.0 0.0–0.0 54.7 .03

Other 0.5 0.3–0.7 0.0 0.0–0.1 290.1 ,.001

ED volume

Low (,4000) 2.5 2.2–2.9 3.9 3.5–4.3 52.6 ,.001

Medium (4000–9999) 6.3 5.4–7.2 6.8 5.9–7.6 7.4 .23

High (10 000–24 999) 4.3 3.4–5.2 8.0 6.5–9.4 84.0 ,.001

Very high (25 000–49 999) 1.6 0.8–2.4 3.5 2.0–5.0 117.4 .01

Extremely high ($50 000) 1.1 0.2–2.0 3.3 1.5–5.1 206.0 .02

Children’s hospital

Nonchildren’s hospital 14.6 13.5–15.8 22.7 21.0–24.4 55.1 ,.001

Children’s hospital 1.2 0.3–2.1 2.7 0.9–4.5 120.6 .08

Hospital urban-rural location

Large metropolitan area with at least 1 million residents 7.0 5.9–8.1 11.9 10.3–13.4 70.4 ,.001 Small metropolitan areas with,1 million residents 4.2 3.6–4.7 8.9 7.8–10.0 114.1 ,.001

Micropolitan areas 1.7 1.5–1.9 2.0 1.6–2.3 15.3 .11

Not metropolitan or micropolitan (nonurban residual) 0.7 0.6–0.8 1.0 0.8–1.2 41.4 .001 NEC, not elsewhere classifiable.

aInclusive of the following: CCS 653, delirium dementia and amnestic and other cognitive disorders; CCS 654, developmental disorders; CCS 655, disorders usually diagnosed in infancy

We used US Census data to estimate the population of corresponding age groups and then calculated incidence rates per 1000 population by demographics, diagnosis category, and hospital characteristics. We usedttests to determine the statistical significance of the difference between the rates. We calculated the percentage of changes from 2007 to 2016 and confidence intervals. All the analyses were done by using SAS (Enterprise Guide, Version 7.11 HF3 [SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC]).

RESULTS

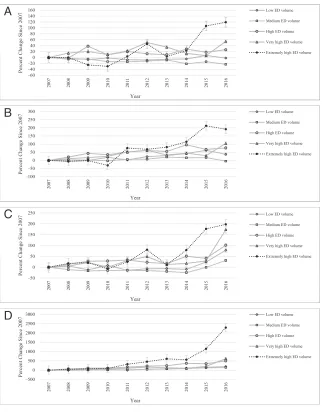

Over the 10-year study period, pediatric ED visits were stable; however, pediatric ED visits for all mental health disorders rose 60% (P,.001) (Table 1, Fig 1). Mental health ED visits among all 3 age tertiles rose, most notably a 68% increase in visits among the 15- to 17-year-old group (P,.001).

Significant rate increases were also observed among both sexes and was more pronounced among girls, with 74% (P,.001). Anxiety disorders (CCS 651) and impulse control disorders (CCS 656) significantly increased by 117% (P,.001) and 111% (P,.001), respectively (Table 1). All substance use disorders rose by 75%

(P,.001), with alcohol-related disorders decreasing by nearly 40% (P,.001), whereas substance use disorders significantly increased by .150% (P,.001) (Table 1, Fig 1). ED visits for deliberate self-harm increased 329% (P,.001) over the 10-year study period (Table 1, Fig 1). The rates for treated and released and transferred to another facility both rose 70% and 134%, respectively (P,.001; Table 1).

Significant rate increases were observed among nearly all ED volumes, except for medium-volume

facilities (P= .23), and was most pronounced among facilities with higher pediatric ED volumes

(Table 1, Fig 2). Although these types of visits rose 120% in children’s hospital EDs (P= .08), the absolute rate change among nonchildren’s hospital EDs was much greater, increasing from 14.6 per 1000 to 22.7 per 1000, a difference of 55% (P,.001) (Table 1). Similarly, pediatric mental health ED visits rose among all urban-rural locations; although greatest among the large and small metropolitan areas (P,.001), a 41% increase was observed among EDs classified as neither metropolitan nor micropolitan (P= .001) (Table 1, Fig 3).

DISCUSSION

Over the 10-year study period, pediatric ED visits were stable; however, pediatric ED visits for all mental health disorders rose 60%. Importantly, we observed a threefold increase in ED visits for deliberate self-harm, similar to trends reported by authors of other studies, suggesting that children are increasingly engaging in self-harm.9,10,24

Similarly, Torio et al4found increasing visits by children for mental health conditions between 2006 and 2011, and Kalb et al’s10 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey study found similar trends, particularly among those presenting for a suicide-related visit. However, neither of these studies examined hospital characteristics,

specifically the number of pediatric ED visits, and the data used are older.

We found that all substance use disorders rose 75%, largely driven by the almost twofold increase in the substance use disorders subgroup and not the alcohol disorders subgroup, which other studies have FIGURE 1

shown.4,25The rate increase in substance use disorders, despite the decline in alcohol use disorders, bears further investigation, especially as the opiate epidemic continues to escalate. EDs, regardless of pediatric specialty, volume, and location, will need to be prepared to handle these cases.26,27

Although the increased rate of pediatric mental health visits was greatest among high-pediatric-volume EDs, our results show that all

EDs, regardless of pediatric volume, experienced increased visits by children for mental health disorders. These visits increased by one-half among low-pediatric-volume EDs.28 The National Pediatric Readiness Assessment, conducted in 2013, found that lower-pediatric-volume EDs, with,4000 pediatric visits per year, and rural EDs are less prepared for all pediatric emergencies, and only one-third have pediatric mental health policies or mental health transfer agreements.7,11,13,29–31Our

findings of increased pediatric ED visits for mental health at smaller-volume EDs in rural centers are concerning given the potential decreased pediatric readiness for children with mental health problems. It will be important to focus future mental health

preparedness efforts and resources on all hospital EDs, particularly smaller-volume and rural EDs, and not just on children’s hospital EDs.28 HRSA’s recently published Critical Crossroads Care Pathway toolkit for EDs further highlights the rising rates of pediatric behavioral health conditions amid the gaps in hospital preparedness. This is a toolkit for EDs that is focused on pediatric mental health visits and offers a customizable framework with resources that can be used in all settings to improve the coordination and continuity of care for children presenting with mental health disorders.8Toolkits and online trainings addressing other important components of pediatric readiness, such as interfacility transfer

guidelines, are available and scalable to work within the resources available.32–34They offer pragmatic, actionable recommendations to effect change, especially in less-resourced, rural EDs.31

An opportunity to increase mental health services in rural, lower-volume EDs could include tele-mental health services. Telemedicine could also provide an avenue for increasing access to behavioral health specialists who can screen, assist with acute interventions, and support connections to continued care within the community, thereby avoiding long-distance transfers, transportation costs, and delays in care.35Recent literature looking at the use of telephone consultation programs on the impact of

children’s mental health care use have shown that the accessibility of these programs has led to greater FIGURE 2

receipt of mental health treatment of children.36

There is a nationwide shortage of mental health care providers, especially in nonurban areas.37–39 This gap between the supply of providers and the demand for mental health services has become especially pronounced among those who specialize in providing care to children.37,38,40,41This shortage will have a direct impact on the

accessibility and quality of mental

health care of children, particularly those who live in rural areas, are younger, and are uninsured.42–46

As the number of pediatric mental health visits continues to rise in EDs, research is needed to identify actionable solutions that will better equip all EDs with the tools, personnel, and resources to better manage these cases. Solutions like screening and assessment efforts for suicidal ideation, a requirement of the Joint Commission for all patients

being evaluated for behavioral health conditions, may impact and improve the quality and safety of care for children now and in years to come.47Further work exploring alternative care delivery methods, such a telepsychiatry and establishing partnership programs with institutions that have specialized pediatric mental health resources, can better ensure continuity of care and help address the mental health crisis that US EDs are facing.

This study has some limitations. NEDS is a national database but does not have patient identifiers that would allow for tracking of ED recidivism. Also, by design, NEDS does not have a primary diagnosis code, so children may be presenting for some reason other than their mental health condition. However, ED care has increasingly become more patient centered and mental health sensitive so that providers can adjust their practice to deliver more mental health–informed care. There is also the potential that cases were missed if the child did not have a diagnosis for one of the mental health conditions before presentation to the ED. However, because we limited our analysis to age 5 years and above, age of onset for these conditions is more likely to have occurred by then. Information on presence of inpatient pediatric psychiatric beds and on transfers to appropriate facilities (eg, pediatric transfer guidelines, interfacility agreements, etc) is not available in NEDS. The ability of NEDS to identify children’s hospitals is limited and as such does not explicitly sample children’s hospitals. We circumvented this by categorizing each facility by the median age of the patient; however, this may not have been foolproof, which may explain how the rate change was not statistically significant.

FIGURE 3

CONCLUSIONS

Although the total number of pediatric ED visits has remained stable, visits among children with mental health disorders have steadily risen, with ED visits by children presenting with deliberate self-harm tripling over the 10-year study period. The majority of children presenting with mental health disorders did not seek care at specialized pediatric EDs. We demonstrated significantly increased visits by children with mental health disorders to

small-pediatric-volume, rural EDs that may be least likely to be prepared to provide higher-level pediatric care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thefindings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the HRSA. The authors would like to acknowledge Doug MacDowell for his assistance with the preparation of figures and tables.

ABBREVIATIONS

CCS: Clinical Classification Software

ED: emergency department HRSA: Health Resources and

Services Administration ICD-9:International Classification

of Diseases,Ninth Revision ICD-10:International Classification

of Diseases,10th Revision NEDS: Nationwide Emergency

Department Sample NPRP: National Pediatric

Readiness Project

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright © 2020 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE:The authors have indicated they have nofinancial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING:No external funding.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST:The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

COMPANION PAPER:A companion to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2019-3542.

REFERENCES

1. Institute of Medicine.Emergency Care for Children: Growing Pains. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007

2. Mojtabai R. Trends in contacts with mental health professionals and cost barriers to mental health care among adults with significant psychological distress in the United States: 1997-2002.

Am J Public Health. 2005;95(11): 2009–2014

3. Sareen J, Jagdeo A, Cox BJ, et al. Perceived barriers to mental health service utilization in the United States, Ontario, and the Netherlands.Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(3):357–364

4. Torio CM, Encinosa W, Berdahl T, McCormick MC, Simpson LA. Annual report on health care for children and youth in the United States: national estimates of cost, utilization and expenditures for children with mental health conditions.Acad Pediatr. 2015; 15(1):19–35

5. Plemmons G, Hall M, Doupnik S, et al. Hospitalization for suicide ideation or

attempt: 2008-2015.Pediatrics. 2018; 141(6):e20172426

6. Abrams A, Badolato G, Goyal M. Racial disparities in pediatric mental health-related emergency department visits: afive-year multi-institutional study. In: Proceedings from the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference & Exhibition; November 2, 2018, 2018; Orlando, FL

7. Remick K, Gausche-Hill M, Joseph MM, Brown K, Snow SK, Wright JL; AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine and Section on Surgery; American College of Emergency Physicians Pediatric Emergency Medicine Committee; Emergency Nurses Association Pediatric Committee. Pediatric readiness in the emergency department.Pediatrics. 2018; 142(5):e20182459

8. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau.Critical

Crossroads Pediatric Mental Health

Care in the Emergency Department: A Care Pathway Resource Toolkit. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2019

9. Whitfill T, Auerbach M, Scherzer DJ, Shi J, Xiang H, Stanley RM. Emergency care for children in the United States: epidemiology and trends over time.

J Emerg Med. 2018;55(3):423–434 10. Kalb LG, Stapp EK, Ballard ED, Holingue

C, Keefer A, Riley A. Trends in psychiatric emergency department visits among youth and young adults in the US.Pediatrics. 2019;143(4): e20182192

11. Grupp-Phelan J, Harman JS, Kelleher KJ. Trends in mental health and chronic condition visits by children presenting for care at U.S. emergency

departments.Public Health Rep. 2007; 122(1):55–61

13. Santucci KA, Sather J, Baker MD. Emergency medicine training

programs’educational requirements in the management of psychiatric emergencies: current perspective.

Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19(3):154–156 14. Sheridan DC, Spiro DM, Fu R, et al.

Mental health utilization in a pediatric emergency department.Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(8):555–559

15. Ames SG, Davis BS, Marin JR, et al. Emergency department pediatric readiness and mortality in critically ill children.Pediatrics. 2019;144(3): e20190568

16. Gausche-Hill M, Ely M, Schmuhl P, et al. A national assessment of pediatric readiness of emergency departments.

JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(6):527–534 17. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

(HCUP). Overview of the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS). Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq. gov/nedsoverview.jsp. Accessed December 13, 2017

18. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Databases. Available at: https:// www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/databases.jsp. Accessed December 13, 2017

19. Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustün TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature.Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(4):359–364 20. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

(HCUP). Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/ toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed August 9, 2019

21. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM Fact Sheet. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq. gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccsfactsheet.jsp. Accessed August 9, 2019

22. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Beta Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-10-PCS. Available at: https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/

toolssoftware/ccs10/ccs10.jsp. Accessed August 9, 2019

23. United States Census Bureau. Metropolitan and micropolitan. Available at: https://www.census.gov/

programs-surveys/metro-micro.html. Accessed August 9, 2019

24. Bridge JA, Olfson M, Fontanella CA, Marcus SC. Emergency department recognition of mental disorders and short-term risk of repeat self-harm among young people enrolled in medicaid.Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018;48(6):652–660

25. Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2018. In:Secondary School Students, vol. Vol 1. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2019

26. Allareddy V, Rampa S, Allareddy V. Opioid abuse in children: an emerging public health crisis in the United States!.Pediatr Res. 2017;82(4):562–563 27. Mazer-Amirshahi M, Mullins PM,

Rasooly IR, van den Anker J, Pines JM. Trends in prescription opioid use in pediatric emergency department patients.Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014; 30(4):230–235

28. Gausche-Hill M, Schmitz C, Lewis RJ. Pediatric preparedness of US emergency departments: a 2003 survey.

Pediatrics. 2007;120(6):1229–1237 29. Doupnik SK, Esposito J, Lavelle J.

Beyond mental health crisis

stabilization in emergency departments and acute care hospitals.Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20173059

30. Seidel JS, Hornbein M, Yoshiyama K, Kuznets D, Finklestein JZ, St Geme JW Jr.. Emergency medical services and the pediatric patient: are the needs being met?Pediatrics. 1984;73(6): 769–772

31. Pilkey D, Edwards C, Richards R, Olson LM, Ely M, Edgerton EA. Pediatric readiness in critical access hospital emergency departments.J Rural Health. 2019;35(4):480–489 32. Emergency Medical Services for

Children. Interfacility transfer toolkit. Available at: https://emscimprovement. center/resources/publications/ interfacility-transfer-tool-kit/. Accessed January 10, 2018

33. Emergency Medical Services for Children. Readiness toolkit. Available at: https://emscimprovement.center/

projects/pediatricreadiness/readiness-toolkit/. Accessed January 5, 2018

34. Emergency Medical Services for Children. Ensuring pediatric readiness for all emergency departments. 2017. Available at: https://emscimprovement. center/about/nprp-white-paper/. Accessed January 5, 2018

35. Spooner SA, Gotlieb EM; Committee on Clinical Information Technology; Committee on Medical Liability. Telemedicine: pediatric applications.

Pediatrics. 2004;113(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/ 113/6/e639

36. Stein BD, Kofner A, Vogt WB, Yu H. A national examination of child psychiatric telephone consultation programs’ impact on children’s mental health care utilization.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(10):1016–1019 37. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

(HCUP). Shortage areas. Available at: https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/shortage-areas. Accessed December 13, 2017

38. Sills MR, Bland SD. Summary statistics for pediatric psychiatric visits to US emergency departments, 1993-1999.

Pediatrics. 2002;110(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/ 110/4/e40

39. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). National projections of supply and demand for selected behavioral health practitioners, 2013-2025. 2016. Available at: https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/ default/fi les/bhw/health-workforce-analysis/research/projections/ behavioral-health2013-2025.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2019

40. Thomas CR, Holzer CE III. The continuing shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(9):1023–1031 41. Koppelman J. Children with mental

disorders: making sense of their needs and the systems that help them.NHPF Issue Brief. 2004;(799):1–24

42. Kelleher KJ, Gardner W. Out of sight, out of mind - behavioral and developmental care for rural children.N Engl J Med. 2017;376(14):1301–1303

112(4). Available at: www.pediatrics. org/cgi/content/full/112/4/e308

44. Larkin GL, Claassen CA, Emond JA, Pelletier AJ, Camargo CA. Trends in U.S. emergency department visits for mental health conditions, 1992 to 2001.

Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(6):671–677 45. Robinson LR, Holbrook JR, Bitsko RH,

et al. Differences in health care, family,

and community factors associated with mental, behavioral, and developmental disorders among children aged 2–8 years in rural and urban areas -United States, 2011–2012.MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(8):1–11 46. Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet

need for mental health care among US children: variation by ethnicity and

insurance status.Am J Psychiatry. 2002; 159(9):1548–1555

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2019-1536 originally published online May 11, 2020;

2020;145;

Pediatrics

Stanley

Charmaine B. Lo, Jeffrey A. Bridge, Junxin Shi, Lorah Ludwig and Rachel M.

2016

−

Children's Mental Health Emergency Department Visits: 2007

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/145/6/e20191536 including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/145/6/e20191536#BIBL This article cites 27 articles, 8 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/emergency_medicine_

Emergency Medicine

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2019-1536 originally published online May 11, 2020;

2020;145;

Pediatrics

Stanley

Charmaine B. Lo, Jeffrey A. Bridge, Junxin Shi, Lorah Ludwig and Rachel M.

2016

−

Children's Mental Health Emergency Department Visits: 2007

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/145/6/e20191536

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/suppl/2020/05/08/peds.2019-1536.DCSupplemental Data Supplement at:

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.