Work Hours

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: Most studies have found that extended work shifts increase resident sleep deprivation and medical errors. To eliminate such shifts, many residency programs are implementing night-team systems. However, the effects of these systems on resident sleep and work hours are unclear.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: After implementation of a night-team system on general pediatric wards, there were borderline-significant decreases in work hours and shift length. Unexpectedly, however, sleep time decreased significantly. Specific features of the schedule (eg, reduced staffing) likely contributed to decreased sleep.

abstract

OBJECTIVE:In 2009, Children’s Hospital Boston implemented a night-team system on general pediatric wards to reduce extended work shifts. Residents worked 5 consecutive nights for 1 week and worked day shifts for the remainder of the rotation. Of note, resident staffing at night decreased under this system. The objective of this study was to assess the effects of this system on resident sleep and work hours.

METHODS:We conducted a prospective cohort study in which resi-dents on the night-team system logged their sleep and work hours on work days. These data were compared with similar data collected in 2004, when there was a traditional call system.

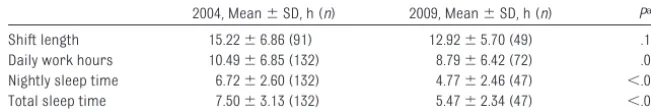

RESULTS:In 2004 and 2009, mean shift length was 15.22⫾6.86 and 12.92⫾5.70 hours, respectively (P⫽ .161). Daily work hours were 10.49⫾6.85 and 8.79⫾6.42 hours, respectively (P⫽.08). Nightly sleep time decreased from 6.72⫾2.60 to 4.77⫾2.46 hours (P⬍.001). Total sleep time decreased from 7.50⫾3.13 to 5.47⫾2.34 hours (P⬍.001).

CONCLUSIONS:Implementation of a night-team system was unexpect-edly associated with decreased sleep hours. As residency programs create work schedules that are compliant with the 2011 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education duty-hour standards, resident sleep should be monitored carefully.Pediatrics2011;128:1142–1147

AUTHORS:Kao-Ping Chua, MD,a,bMary Beth Gordon, MD,c

Theodore Sectish, MD,band Christopher P. Landrigan,

MD, MPHb,d,e

aHarvard Pediatric Health Services Research Fellowship and bDepartment of Medicine, Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston,

Massachusetts;cDepartment of Society, Human Development,

and Health, Harvard School of Public Health;dDivision of Sleep

Medicine, School of Medicine, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts andeDepartment of Medicine, Brigham and

Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

KEY WORDS

graduate medical education, accreditation, internship, residency, staffing, sleep deprivation, workload, night team

ABBREVIATION

ACGME—Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2011-1049

doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1049

Accepted for publication Aug 22, 2011

Address correspondence to Christopher P. Landrigan, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Children’s Hospital Boston, 300 Longwood Ave, Boston, MA 02115. E-mail: clandrigan@partners. org

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright © 2011 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine esti-mated that between 44 000 and 98 000 US patients per year die as a result of medical errors.1 Recent studies

sug-gested that rates of harm attributable to medical care are not decreasing.2,3

In July 2003, the Accreditation Council

for Graduate Medical Education

(ACGME) began enforcing resident duty-hour standards, partially in re-sponse to concerns that resident sleep deprivation contributes to medical er-rors.4,5Although the guidelines were

designed to improve sleep and patient safety, the literature suggests that they have not affected either out-come.6–9 In a study of pediatric

resi-dency programs, numbers of total work hours, sleep hours, and medica-tion errors were unchanged after im-plementation of the 2003 ACGME duty-hour standards.6

In recent years, the Institute of Medi-cine and the ACGME have called for more-substantive regulation of work hours.7,10,11In response, residency

pro-grams have experimented with multi-ple approaches to reduce work hours. Many of these approaches have contin-ued to allow extended work shifts (ⱖ16 consecutive hours), despite evi-dence that such shifts are associated with increased numbers of resident needlestick injuries,12a higher risk of

motor vehicle crashes,13 and

in-creased numbers of medical errors.14

Several residency programs have im-plemented schedules that reduce or eliminate extended work shifts, with mostly positive results. In the Intern Sleep and Patient Safety Study, ICU in-terns working on a schedule that re-stricted them to ⬍16 consecutive work hours committed fewer serious medical errors than did interns work-ing on an every-third-night call sched-ule.15,16A systematic review by Levine

et al17found that 7 of 11 residency

pro-grams experienced improved safety or quality of care after eliminating or

re-ducing extended work shifts; none ex-perienced worsened patient safety or quality.

To eliminate or to reduce extended work shifts, some residency programs have implemented night-team systems in which residents alternate between working strings of day and night shifts. Many more programs likely will imple-ment such systems in response to the ACGME 2011 duty-hour standards, which prohibit shifts of⬎16 hours for interns. However, the effects of night-team systems on resident sleep and work hours are unclear. In this study, we measured sleep and work hours before and after implementation of a night-team system at Children’s Hospi-tal Boston. We hypothesized that the night-team system would decrease work hours and increase sleep, com-pared with an overnight call system.

METHODS

Study Setting

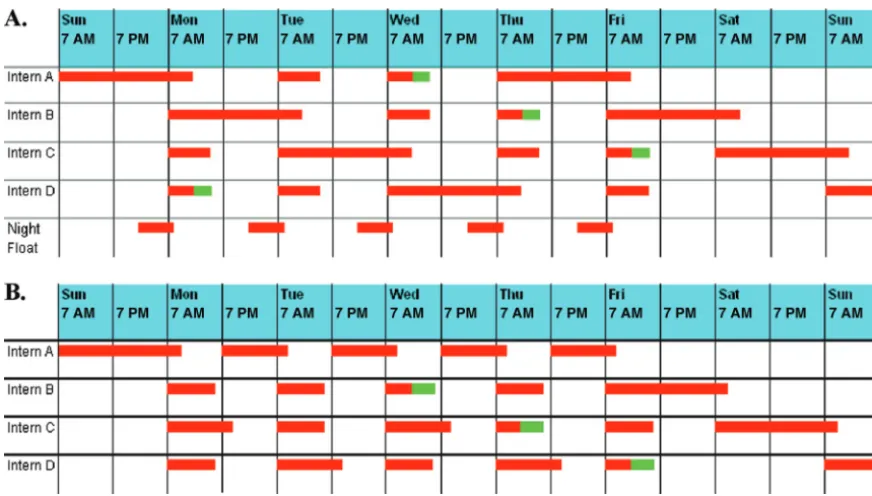

This study was conducted on 2 general pediatric inpatient wards at Children’s Hospital Boston. The Children’s Hospi-tal Boston institutional review board approved the study protocol. Data were collected in the spring of 2004 (as part of a study of the 2003 ACGME duty-hour standards6) and again in the

spring of 2009. In the spring of 2004, each ward was staffed by a team of 4 interns, 4 senior residents (a primary senior resident who supervised during the day, an associate senior resident who supervised when the primary se-nior resident was not present, and 2 senior residents who cross-covered for night call), and a “night float” se-nior resident (described below). The 4 interns and senior residents took call every fourth night, with a maximal scheduled shift length of 30 hours (Fig 1A). On Sunday through Thursday, on-call interns and residents took care of current ward patients and admitted new patients until midnight. From

mid-night until 8AM, the senior night float resident covered all new admissions; on-call interns and residents re-mained in the hospital to handle all other patient care issues. There was no night float resident on Friday or Saturday.

In the spring of 2009, Children’s Hospi-tal Boston implemented a night-team system on its 2 general pediatrics in-patient wards. Each ward team was staffed by a team of 4 interns and 2 senior residents (a primary senior resident and an associate senior resi-dent). The night float position was eliminated. In this system, each intern worked 1 “night week” and 3 “day weeks” during the 28-day rotation. During their night week, interns had a 25- to 26-hour shift starting Sunday morning, followed by four 13- to 14-hour night shifts, starting at 7PM, on Monday through Thursday. During the 3 day weeks, interns had five 10- to

12-hour daytime shifts on Monday

through Friday. They also stayed over-night on 1 Friday (which resulted in a 27–28-hour Friday shift) and worked one 27- to 28-hour Saturday shift (Fig 1B). The length of intern daytime shifts varied. On weekdays, 1 daytime intern stayed until⬃7:30 to 8:00PMto sign out the service to the night intern (which resulted in a 12- to 13-hour shift). The other 2 interns generally worked until 5 PM (10-hour shift) unless they had their weekly afternoon continuity clinic.

working nights or was in the afternoon continuity clinic.

Data Sources

In the spring of 2004, data on sleep and work hours were collected for 1 month from all residents at Children’s Hospi-tal Boston, as part of the ACGME duty-hours study.6 For the current study,

data from the 2 general pediatric inpa-tient wards were extracted from the larger data set. Data were collected by using written logs, which had been val-idated previously through compari-sons with continuous ambulatory poly-somnographic data and third-party observations of work hours.6,15,16Work

hour questions included when the sub-ject arrived and left work. Sleep hour questions included what time the sub-ject tried to fall asleep, how long it took the subject to fall asleep, when the subject woke up, and the duration of any daytime naps. Data were collected

only from the 4 primary interns and the primary senior resident on each team (10 possible participants).

In the spring of 2009, data on sleep and work hours on the 2 general pediatric wards were collected for 1 week in

April 2009, May 2009, and June 2009. Questions on sleep and work hours from the 2004 study were appended to an online survey for a separate ongo-ing study that collected data for 1 week during each 28-day rotation in general pediatrics.18Consequently, the timing

of data collection differed between 2004 and 2009. Participants were asked to complete the online survey every morning during the weeklong data collection period. In contrast to 2004, data were collected from 6 mem-bers of each team: the 4 primary in-terns, the primary senior resident, and the associate senior resident (36 pos-sible participants). All eligible subjects

were invited to participate; to maxi-mize participation rates, we person-ally contacted subjects and sent re-minder e-mails.

In 2009, the first question on the online survey asked whether the subject had worked that day. If the subject had not worked, the survey was terminated. Because of this design issue, we do not have sleep data from residents in 2009 who did not work on the day they com-pleted the survey. As discussed below, to address possible bias resulting from this problem, we conducted a secondary analysis of sleep hours that excluded the daily logs from 2004 that were collected from residents who did not work on the day they completed the logs.

Data Analyses

The main outcomes of interest were mean shift length, daily work hours,

⬃ ⬃

midnight until 8AMon Sunday through Thursday. B, Night-team schedule in 2009. Intern A is the night-team intern and starts with a 25- to 26-hour shift on Sunday, followed by four 13- to 14-hour night shifts, starting at 7PM, on Monday through Thursday. Intern B works 10- to 12-hour day shifts on Monday through Thursday and then works a 27- to 28-hour shift from Friday morning until Saturday morning. Intern C works day shifts on Monday through Friday and works a 27- to 28-hour shift on Saturday. Intern D works day shifts on Monday through Friday and then becomes the night-team intern and works a 25- to 26-hour shift on Sunday. In subsequent weeks, interns switch schedules (eg, intern A takes the intern B schedule). During the day, 1 intern stayed until 7:30 to 8:00PM

nightly sleep time, and total sleep time. Shift length was calculated by deter-mining the number of consecutive

work hours between arrival and de-parture from the hospital. Daily work hours were defined as hours of work in a 24-hour period from 6AMto 6AM. For instance, a resident who worked a day-time shift from 7 AMto 7 PM was as-signed a daily work hour total of 12 hours and a shift length of 12 hours; a

resident who worked a night shift from 7PMto 9AMwas assigned a daily work-hour total of 11 work-hours for the first part of the shift and 3 hours for the second part of the shift (which resulted in 2 work-hour data points for the shift). Nightly sleep time was calculated by determining the number of hours be-tween when a resident first tried to go

to sleep for the night and when the subject awoke in the morning, then subtracting the amount of time it took for the resident to fall asleep. Total sleep time (defined as the total amount of sleep in a 24-hour period) was deter-mined by adding any reported daytime naps to nightly sleep time.

The 4 primary outcomes were

com-pared between 2004 and 2009 by using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, because they were not normally distributed. All reported Pvalues are 2-sided, and P values of⬍.05 are considered statisti-cally significant. Analyses were per-formed by using Stata 11.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

Power

There were a total of 132 daily logs of

work hours and sleep in 2004. To have 80% power to detect a 25% difference in work and sleep hours in 2009, as-suming a 2-sided␣error of .05, we cal-culated that we would need 52 daily reports of shift length, 108 daily ports of daily work hours, 38 daily re-ports of nightly sleep time, and 44 daily reports of total sleep time.

RESULTS

Response Rates

In 2004, 100% of the 10 eligible subjects provided ⱖ1 daily report of work hours and sleep (total of 132 daily re-ports). In 2009, 58.3% of the 36 eligible subjects providedⱖ1 daily report (to-tal of 77 daily reports).

Sleep and Work Hour Data

As shown in Table 1, mean shift length was 15.22⫾ 6.86 hours in 2004 and 12.92⫾5.70 hours in 2009 (P⫽.161). Mean daily work hours were 10.49⫾ 6.85 hours in 2004 and 8.79⫾ 6.42 hours in 2009 (P ⫽ .08). Between 2004 and 2009, mean nightly sleep time decreased from .6.72⫾2.60 to 4.77 ⫾ 2.46 hours (P ⬍ .001) and mean total sleep time decreased from 7.50⫾3.13 to 5.47⫾2.34 hours (P ⬍.001). Because not every daily report had complete data for work hours and sleep in 2009, there were

⬍77 data points for the 4 outcomes. Overall, subjects provided data for 49 separate shifts in 2009, which pro-duced 72 data points for daily work hours.

We were concerned that sleep hour data in 2009 might be biased by the fact that we did not have sleep data from subjects who did not complete a full survey if they were not sched-uled to work. Overall, 12 (15.6%) of the 77 daily logs from 2009 were from residents who did not work that day, compared with 21 (15.9%) of the 132 daily logs in 2004. We conducted a secondary analysis that excluded these 21 logs from 2004, but the

re-sults did not fundamentally alter our conclusion. In that analysis, the mean nightly sleep time in 2004 was 6.55⫾2.70 hours and the mean total sleep time was 7.44 ⫾ 3.33 hours (P⬍.001, compared with 2009 data for both outcomes, Wilcoxon rank-sum test).

DISCUSSION

Main Findings

We found that implementation of a night-team system was associated with borderline-significant reductions in shift length and daily work hours. Contrary to our hypothesis, it also was associated with decreases in nightly and total sleep times. The decrease in total sleep time is particularly note-worthy, because it suggests that resi-dents were not making up for de-creased nightly sleep times by napping more during the day. Our study does not indicate that all efforts to eliminate or to reduce extended work shifts af-fect sleep adversely; rather, it indi-cates that implementation of this spe-cific night-team system at our hospital was associated with worsened sleep. Because of these negative sleep ef-fects and workflow difficulties, Chil-dren’s Hospital Boston reverted tem-porarily to a traditional overnight call schedule in July 2009. In July 2011, the hospital implemented a redesigned night-team schedule that sought to ad-dress many of the shortcomings of the earlier iteration.

Our findings differed from those of previous studies, which generally found improvements in sleep after the

TABLE 1 Comparison of Resident Work and Sleep Times With Traditional (2004) and Night-Team (2009) Systems

2004, Mean⫾SD, h (n) 2009, Mean⫾SD, h (n) Pa

Shift length 15.22⫾6.86 (91) 12.92⫾5.70 (49) .161

Daily work hours 10.49⫾6.85 (132) 8.79⫾6.42 (72) .08

Nightly sleep time 6.72⫾2.60 (132) 4.77⫾2.46 (47) ⬍.001

Total sleep time 7.50⫾3.13 (132) 5.47⫾2.34 (47) ⬍.001

aWilcoxon rank-sum test.

reduction or elimination of extended work shifts.17Several aspects of the

in-tervention schedule in this study may explain this discrepancy. Unlike many successful work hour interventions, the system we studied reduced but did not eliminate extended work shifts.17

Overall, the night-team system re-quired each resident to work 3 ex-tended work shifts per 28-day rotation, instead of 7 extended work shifts in the every-fourth-night call system of 2004. Another potential reason for the dis-crepancy is that residents in our study worked 5 nights in a row, starting with a 25- to 26-hour shift on Sunday. The Institute of Medicine recommended limiting residents to no more than 4 consecutive nights of work, in light of previous studies that showed that working⬎3 or 4 nights in a row in-creased the risk of errors in multiple occupations.7,19Because residents

be-gan their string of nights with a 25- to 26-hour shift, they could not take an afternoon nap before their first night shift (an intervention that mitigates the pressure to sleep after extended wakefulness and minimizes the circa-dian rhythm-based impairment in per-formance that typically occurs in the middle of the night).20Finally, the

night-team system decreased resident staff-ing overnight, because the night float position was eliminated. This might have led to increased resident work-loads and decreased sleep while on duty at night.

The finding that sleep time decreased after implementation of our

night-team system is particularly timely, given the new ACGME 2011 duty-hour standards (Table 2). Those standards include a 16-hour shift limit for interns, which might prompt residency

pro-grams to consider implementing

night-team systems. Our findings should not be taken as a blanket indict-ment of all night-team systems; rather, they should serve as a warning that

residency programs considering

these systems must pay particular at-tention to resident sleep. This is espe-cially true given the growing body of literature showing that resident sleep deprivation is associated with in-creased numbers of medical errors, increased risk of resident motor vehi-cle accidents, and increased risk of resident occupational exposures.5,15,16

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. First, our results might be positively or negatively confounded by changes that occurred between 2004 and 2009, in-cluding the institution of a computer-ized physician order entry system and changes in the cohorting of patients.18

In addition, there might have been dif-ferences in patient volume or acuity on general pediatric wards between 2004 and 2009. Because of these potential confounding factors and the design of our study, we cannot be certain that institution of the night-team system was the sole determinant of decreased resident sleep. However, no factor other than the changes in resident work schedules was intended to alter

creases in shift length and work hours, the study was underpowered to deter-mine whether this difference was real. In contrast, the study was well pow-ered to detect the observed 25% to 30% decreases in nightly sleep and to-tal sleep time. We conclude that it is unclear whether shift length and work hours decreased with the night-team system but sleep time decreased con-vincingly. Third, the study did not mea-sure outcomes such as medical er-rors, medical education, adequacy of patient handoffs, and resident safety. These are critical outcomes that should be examined in future studies of resident work schedules. Fourth, data from the baseline group in 2004 were obtained from 10 residents. Res-idents have different sleeping habits while on call, and this small sample of 10 residents might not have been representative of all residents. Fi-nally, we evaluated only 1 possible night-team system in a single pediat-ric residency program with a limited number of residents. Differences in the designs of night-team systems and hospital dynamics might signifi-cantly affect sleep and work hours. Importantly, this night-team system was not compliant with the 2011

ACGME duty-hour standards.

Al-though our study may provide guid-ance to residency programs that are implementing the new standards, it should not be used as a commentary on the standards themselves.

CONCLUSIONS

As residency programs consider solu-tions to achieve compliance with the 2011 ACGME duty-hour standards, it will be important to remember that not all solutions are created equal. In our study, we found adverse effects on sleep after institution of a night-team system that reduced but did not elim-inate extended work shifts,

sched-Minimum of 1 d/wk free of duty, averaged over 4-wk period PGY-1 interns must not exceed 16 h of continuous duty

PGY-2 residents and above must not exceed 24 h of continuous duty plus maximum of 4 h for effective transition of care

Minimum of 8 h between duty periods for all residents; intermediate-level residents must have 14 h free of duty after 24 h of in-house duty

Maximum of 6 consecutive nights of in-house night float

Maximal call frequency of every third night, averaged over 4-wk period

uled residents to work 5 nights in a row beginning with a 25- to 26-hour shift, and reduced staffing at night. Ideally, attempts to reduce extended work shifts should improve sleep without reducing staffing. These ef-forts may require an initial infusion

of resources, but they may ultimately be cost-effective if they decrease ad-verse events.21 Future research

should seek to measure how alterna-tive approaches to eliminating ex-tended work shifts affect resident sleep and patient safety.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Fred Lovejoy Resident Research and Educa-tion Fund at Children’s Hospital Bos-ton, Department of Medicine, and the Children’s Hospital Boston Program for Patient Safety and Quality.

REFERENCES

1. Institute of Medicine.To Err Is Human: Build-ing a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999

2. Landrigan CP, Parry G, Bones CB, Hackbarth AD, Goldmann DA, Sharek PJ. Temporal trends in rates of patient harm due to med-ical care. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(22): 2124 –2134

3. Office of the Inspector General.Adverse Events in Hospitals: Methods for Identifying Events. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. Publica-tion OEI-06-08-00221. Available at: www.oig. hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-06-08-00221.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2011

4. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.Report of the ACGME Work Group on Resident Duty Hours. Chicago, IL: Accred-itation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2002

5. Steinbrook R. The debate over residents’ work hours. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16): 1296 –1302

6. Landrigan CP, Fahrenkopf AM, Lewin D, et al. Effects of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education duty hour lim-its on sleep, work hours, and safety. Pediat-rics. 2008;122(2):250 –258

7. Institute of Medicine.Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2008

8. Volpp KG, Rosen AK, Rosenbaum PR, et al. Mortality among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries in the first 2 years following ACGME resident duty hour reform.JAMA. 2007;298(9):975–983

9. Landrigan CP, Barger LK, Cade BE, Ayas NT, Czeisler CA. Interns’ compliance with Ac-creditation Council for Graduate Medical Education work-hour limits.JAMA. 2006; 296(9):1063–1070

10. Volpp KG, Landrigan CP. Building physician work hour regulations from first principles and best evidence.JAMA. 2008;300(10): 1197–1199

11. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Require-ments. 2011. Available at: http://www. acgme.org/acwebsite/home/Common_ Program_Requirements_07012011.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2011

12. Ayas NA, Barger LK, Cade BE, et al. Extended work duration and the risk of self-reported percutaneous injuries in interns. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1055–1062

13. Barger LK, Cade BE, Ayas NT, et al. Extended work shifts and the risk of motor vehicle crashes among interns.N Engl J Med. 2005; 352(2):125–134

14. Barger LK, Ayas NT, Cade BE, et al. Impact of extended-duration shifts on medical errors, adverse events, and attentional failures.

PLoS Med. 2006;3(12):e487

15. Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Cronin JW, et al. Effect of reducing interns’ work hours on

serious medical errors in intensive care u n i t s . N E n g l J M e d. 2 0 0 4 ; 3 5 1 ( 1 8 ) : 1838 –1848

16. Lockley SW, Cronin JW, Evans EE, et al. Effect of reducing interns’ weekly work hours on sleep and attentional failures.N Engl J Med. 2004;351(18):1829 –1837

17. Levine AC, Adusumilli J, Landrigan CP. Ef-fects of reducing or eliminating resident work shifts over 16 hours: a systematic

re-view.Sleep. 2010;33(8):1043–1053 18. Gordon MB, Melvin P, Graham D, et al.

Unit-based care teams and the frequency and quality of physician-nurse communications.

Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(5): 424 – 428

19. Folkard S, Lombari DA, Tucker PT. Shiftwork: safety, sleepiness, and sleep.Ind Health. 2005;43(1):20 –23

20. Landrigan CP, Czeisler CA, Barger LK, Ayas NT, Rothschild JM, Lockley SW. Effective

implementation of work-hour limits and systemic improvements.Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33(11 suppl):19 –29 21. Nuckols TK, Bhattacharya J, Wolman DM,

Ul-mer C, Escarce JJ. Cost implications of re-duced work hours and workloads for resi-dent physicians.N Engl J Med. 2009;360(21): 2202–2215

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2011-1049 originally published online November 28, 2011;

2011;128;1142

Pediatrics

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/128/6/1142

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/128/6/1142#BIBL

This article cites 16 articles, 1 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/standard_of_care_sub

Standard of Care

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/safety_sub

Safety

sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/quality_improvement_

Quality Improvement

_management_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/administration:practice

Administration/Practice Management

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/workforce_sub

Workforce

b

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/medical_education_su

Medical Education following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2011-1049 originally published online November 28, 2011;

2011;128;1142

Pediatrics

Kao-Ping Chua, Mary Beth Gordon, Theodore Sectish and Christopher P. Landrigan

Effects of a Night-Team System on Resident Sleep and Work Hours

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/128/6/1142

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.