Implications of Welfare Reform for Child Health: Emerging Challenges

for Clinical Practice and Policy

Lauren A. Smith, MD, MPH*; Paul H. Wise, MD, MPH*; Wendy Chavkin, MD, MPH‡; Diana Romero, MPhil, MA‡; and Barry Zuckerman, MD*

ABBREVIATIONS. PRWORA, Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act; AFDC, Aid to Families With De-pendent Children; TANF, Temporary Assistance for Needy Fam-ilies; SCHIP, State Child Health Insurance Program; SSI, Supple-mental Security Income.

T

he passage of the Personal Responsibility andWork Opportunity Reconciliation Act

(PRWORA) in 1996 represented one of the most profound developments in American social policy since the Great Society programs of the mid-1960s and has the potential to affect the health of millions of American children. The overall purpose of the legislation, commonly referred to as welfare reform, was to decrease reliance on welfare and in-crease the economic independence of poor families. Its impact has been far-reaching, affecting many de-terminants of child health and well-being, such as family resources, reproductive choices, maternal em-ployment, parental supervision, childcare, and ac-cess to health insurance.

The implementation of PRWORA has been associ-ated with unprecedented declines in the number of children receiving public benefits. In the first 2 years after welfare reform, the number of children receiv-ing welfare benefits fell by 28%.1,2 In addition, the

number of children enrolled in Medicaid, the princi-pal public health insurance program for poor chil-dren in the United States, also fell, despite provisions in the legislation to extend Medicaid coverage to all children who lose welfare benefits.3 Similarly, the

number of children receiving food stamps has dropped by 20% between 1996 and 1998.4 – 6

Al-though there is consensus that both growth in the economy and welfare policies themselves have con-tributed to these declines, the exact proportion attrib-utable to each factor remains unclear.7–9

This discussion considers how these major shifts in public support for poor children and their families are likely to affect patterns of child health and the provision of clinical services to children. It addresses these concerns by exploring 4 related issues: the

el-ements of the welfare legislation most likely to affect child health, the impact of this legislation on enroll-ment in public programs for children, the potential health effects of welfare reform, and the role of pe-diatric and other child health practitioners in ad-dressing these health effects through clinical practice and public advocacy.

ELEMENTS OF WELFARE REFORM LEGISLATION The PRWORA legislation ended the federal guar-antee of income support to poor families by replac-ing the longstandreplac-ing entitlement program Aid to Families With Dependent Children (AFDC) with lim-ited block grants to the states under the new Tem-porary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) pro-gram. Through these block grants, the states were given substantial power over many aspects of wel-fare policy and implementation, which has led to unprecedented variation in state welfare programs. Among the many changes in welfare that PRWORA imposed, there are 6 key elements of the new welfare law that have implications for child health: time lim-its, work requirements, family caps, the uncoupling of TANF and Medicaid, sanctions, and changes in related social programs.

Time Limits

The federal law mandates a 5-year lifetime limit for cash benefits. Once families reach their time limit, benefits are terminated regardless of their social or economic situation. States can institute shorter limits and 23 states have done so; several states have time limits of 2 years or less (Table 1).10 Exemptions and

extensions are permitted for factors such as domestic violence, parent disability, or caring for a young child; however, 18 states do not allow extensions in any circumstance.

Work Requirements

The federal law also mandates that single parents receiving TANF must seek work (Table 1).11In many

states, educational activities such as pursuing high school diploma equivalency, job training, or college, no longer fulfill work requirements. Although 28 states have adopted the federal guideline that ex-empts parents of children younger than 1 year of age from work, 12 states have set the age for exemption much lower at 3 months of age (Table 1). Although states can provide exemptions to women with chron-ically ill children, most states have adopted highly

From the *Department of Pediatrics, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; and the ‡Center for Population and Family Health, Columbia University, New York, New York.

Received for publication Dec 23, 1999; accepted May 8, 2000.

Reprint requests to (L.A.S.) Boston Medical Center, Department of Pediat-rics, Dowling 3 S, 1 Boston Medical Center Pl, Boston, MA 02118. E-mail: lauren.smith@bmc.org

restrictive criteria. For example, in Massachusetts work exemptions are limited to only those women whose children meet SSI disability standards, a prac-tice that has recently been challenged in court.12

Sim-ilarly, state exemptions for when a parent is disabled or a victim of domestic violence have been highly restrictive.13 Failure to comply with work

require-ments can result in reduction or termination of ben-efits (Table 1).

Family Caps

Although there was no specific federal require-ment to eliminate benefits for children born to women already on welfare, states were allowed to do so and 23 states have chosen to restrict cash assis-tance to such family cap children to provide a disin-centive for childbearing while on welfare.10Nineteen

of these states provide no additional assistance, 2 provide partial increases in cash benefits, 1 provides additional assistance as vouchers rather than cash, and 1 provides additional assistance to a third party rather than to the parent (Table 1). For families who have an additional child while on welfare, the family cap restrictions do not reduce total benefits to the family, but effectively result in a decrease in house-hold income per family member. In an additional effort to discourage childbearing while on welfare, 4 states have provisions that require mothers who

have children while receiving TANF to work soon after birth.10,13

Uncoupling of TANF From Medicaid

Before 1996, welfare and Medicaid were adminis-tratively linked. The PRWORA legislation created different eligibility requirements and funding mech-anisms for the 2 programs. Families found ineligible for TANF could still qualify for Medicaid, which remains an entitlement program. PRWORA main-tained Medicaid eligibility guidelines similar to those of the former AFDC program and specified that Medicaid benefits could continue for a transi-tional year after families leave TANF for employ-ment (Table 1). This provision was intended to ad-dress the likelihood that the jobs available to this population may not provide health insurance. The State Child Health Insurance Plan (SCHIP) was also established in 1997 to reduce the number of unin-sured low-income children. By the beginning of fiscal year 1999, the majority of states had begun imple-menting their SCHIP enrollment plans, although the pace of enrollment has varied across states.14

Sanctions

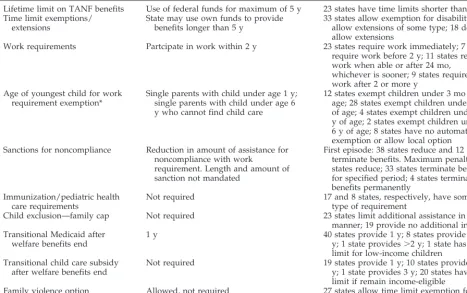

The welfare law mandated that cash benefits must be reduced if parents fail to comply with work re-quirements, a practice that many states had imple-TABLE 1. Selected Elements of PRWORA10,13

Element of Legislation Federal Rule State Implementation Decisions

Lifetime limit on TANF benefits Use of federal funds for maximum of 5 y 23 states have time limits shorter than 5 y Time limit exemptions/

extensions

State may use own funds to provide benefits longer than 5 y

33 states allow exemption for disability; 29 allow extensions of some type; 18 do not allow extensions

Work requirements Partcipate in work within 2 y 23 states require work immediately; 7 states require work before 2 y; 11 states require work when able or after 24 mo,

whichever is sooner; 9 states require work after 2 or more y

Age of youngest child for work requirement exemption*

Single parents with child under age 1 y; single parents with child under age 6 y who cannot find child care

12 states exempt children under 3 mo of age; 28 states exempt children under 1 y of age; 4 states exempt children under 2 y of age; 2 states exempt children under 6 y of age; 8 states have no automatic exemption or allow local option Sanctions for noncompliance Reduction in amount of assistance for

noncompliance with work

requirement. Length and amount of sanction not mandated

First episode: 38 states reduce and 12 states terminate benefits. Maximum penalty: 14 states reduce; 33 states terminate benefits for specified period; 4 states terminate benefits permanently

Immunization/pediatric health care requirements

Not required 17 and 8 states, respectively, have some

type of requirement

Child exclusion—family cap Not required 23 states limit additional assistance in some manner; 19 provide no additional income Transitional Medicaid after

welfare benefits end

1 y 40 states provide 1 y; 8 states provide 1–2

y; 1 state provides⬎2 y; 1 state has no limit for low-income children

Transitional child care subsidy after welfare benefits end

Not required 19 states provide 1 y; 10 states provide 1–2 y; 1 state provides 3 y; 20 states have no limit if remain income-eligible

Family violence option Allowed, not required 27 states allow time limit exemption for domestic violence

Modified with permission from Wise et al. Assessing the effects of welfare reform on reproductive and infant health.Am J Public Health.

1999;89:1514 –1521

mented even before this legislation.13 States vary

regarding the causes, severity, and duration of sanc-tions. For example, some states will impose sanctions if immunization or routine pediatric health care is not appropriately documented (Table 1).

Changes in Related Social Programs

The welfare legislation also included changes in 2 other important programs that benefit low-income children—food stamps and the Supplemental Secu-rity Income (SSI) programs. New restrictions were imposed in the food stamps program, including a reduction of benefit levels and allowances for reduc-tions in food stamp benefits if families were penal-ized under TANF rules.4,15Welfare reform tightened

SSI eligibility by eliminating the Individualized Functional Assessment as a basis for evaluating dis-ability in children and by requiring eligibility rede-terminations.16,17 These individualized assessments

allowed children to be considered disabled if their conditions were of comparable severity to those of an adult or if they had a combination of impairments that did not individually meet disability criteria.18

THE IMPACT OF WELFARE REFORM ON ENROLLMENT IN WELFARE, MEDICAID, AND

RELATED PROGRAMS FOR CHILDREN Since the enactment of PRWORA, there have been substantial declines in enrollment of children in im-portant programs that serve as the safety net for poor children—TANF, Medicaid, food stamps, and SSI. The difference between states in the size of enroll-ment decreases is likely caused by differences in their specific welfare policies as well as their overall economic situation.7,8,19There is evidence that there

is persistent need for these programs despite a strong economy, which has implications for future periods of economic slowdown.20,21

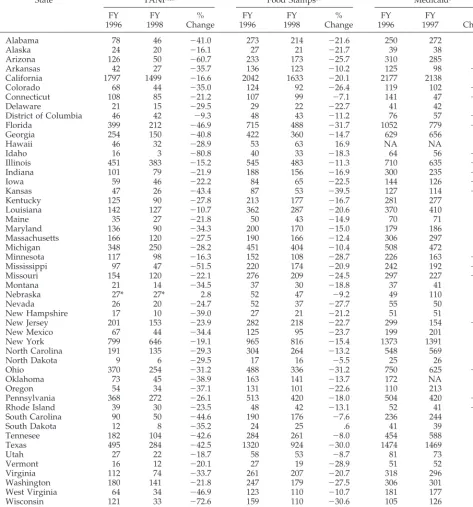

TANF Enrollment

Since the enactment of welfare reform, the number of children receiving welfare benefits decreased by 28%, from 8.6 million in 1996 to 6.2 million in 1998 (Table 2).1,2During this same period, the rate of child

poverty decreased by 1.6%. However, this decrease reflected overall poverty trends and did not neces-sarily represent the experiences of children leaving welfare.22 An even more striking decline occurred

among adults, with the total number of people re-ceiving TANF falling by 43% from 12.2 million in August 1996 to 6.9 million in June of 1999.23

Al-though the welfare caseload began to decline from its peak of 14.2 million in 1994, before passage of wel-fare reform, 61% of the decrease since 1994 occurred in the last 2 years. The size of the drop varies from 12% in Rhode Island and Nebraska to over 80% in Idaho, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.23,24

Medicaid and SCHIP

One problem with evaluating Medicaid enroll-ment trends is the significant time lag in reporting these data.25 Fiscal year 1998 data are only now

becoming available and have yet to be verified. Med-icaid enrollment data compiled from a recent survey

of 21 states are available but do not include informa-tion for children.26However, the data that are

avail-able for the period between 1996 and 1997 indicate that the number of children enrolled in Medicaid fell by 1 million, from 16.3 to 15.3 million, a 6% decrease (Table 2).3,27This reduction occurred while the child

uninsurance rate remained stable at 15%, translating to 11 million uninsured children.21 As with the

TANF decline, the reason for the decreases in Med-icaid enrollment are understood to be multifactorial but are likely to include practical administrative bar-riers resulting from the uncoupling of Medicaid and TANF, as well as improvements in local economic conditions.7,28In addition, part of the decline in

Med-icaid enrollment is attributable to a decrease in the participation rate in the program among poor chil-dren from 63% in 1996 to 58% in 1998.29

The effort to expand coverage to a larger propor-tion of poor children through SCHIP has only offset a portion of the Medicaid declines. A recent survey of the 12 states with the most uninsured children demonstrated that increases in SCHIP enrollment were overshadowed by even larger decreases in Medicaid enrollment, resulting in substantially fewer children enrolled in federally funded health insur-ance programs 3 years after welfare reform.30

In-deed, evidence indicates that there are at least 2.6 million uninsured children eligible for SCHIP and 4.7 million uninsured children eligible for Medic-aid.31,32 SCHIP enrollment data suggest that

al-though enrollment increased by over 50% from 833 000 to 1.3 million between December 1998 and June 1999 this only accounted for 50% of those pre-dicted to be eligible.33 As SCHIP enrollment

pro-ceeds, information must be gathered on how many of these uninsured yet eligible children are captured.

Food Stamps

Food stamps are an important resource for low-income families regardless of whether they receive welfare benefits. Concurrent with the dramatic de-crease in the total number of TANF recipients from 1996 to 1998, there has been a comparable 24% de-crease in overall food stamp enrollment from 24.9 million to 18.9 million participants, the lowest num-ber since 1979.4 In the face of this decline, the

in-creased need for food assistance was documented in a 1999 survey of 26 major cities that found requests for food assistance by families with children in-creased by 15% in the previous year and that two thirds of those requesting food assistance were work-ing.20This evidence suggests that food stamp

enroll-ment cannot be explained only by a decreased need for food assistance. Rather, the overall decline is likely to be attributable to a combination of overall economic conditions, specific tightening of food stamp eligibility requirements under PRWORA and to spillover effects of other welfare reform policies geared to reducing caseloads.4

receiv-ing food stamps.15These declines are not caused by

ineligibility because most families are still eligible because their incomes have remained low after leav-ing welfare.4,34 –38

Not surprisingly, the number of children receiving food stamps also decreased, falling 20% from 13.2 million in 1996 to 10.5 million in 1998 (Table 2).39

This drop accounts for nearly one half of the total decline in food stamp enrollment. In addition, the rate of participation of poor children decreased from 94% to 84% between 1995 and 1997, despite rising rates of demand for subsidized school lunches and emergency food assistance.4

SSI

The SSI program is one of the most important programs providing supplemental income support for families with disabled children. After the stricter eligibility standards for SSI went into effect, elimi-nating the Individualized Assessment Plan and requiring eligibility redeterminations, the overall enrollment dropped by 11%, from 955 000 to 847 000 between December 1996 and December

1999.40 Children who lost their SSI benefits

through redeterminations also lost their Medicaid coverage until this was reinstated by the 1997 Bal-anced Budget Act.18,40

TABLE 2. Enrollment Trends of Children in TANF, Food Stamps, and Medicaid (Population in Thousands*)

State TANF1,2 Food Stamps39 Medicaid3

FY 1996

FY 1998

% Change

FY 1996

FY 1998

% Change

FY 1996

FY 1997

% Change

Alabama 78 46 ⫺41.0 273 214 ⫺21.6 250 272 8.8

Alaska 24 20 ⫺16.1 27 21 ⫺21.7 39 38 ⫺3.5

Arizona 126 50 ⫺60.7 233 173 ⫺25.7 310 285 ⫺8.1

Arkansas 42 27 ⫺35.7 136 123 ⫺10.2 125 98 ⫺21.3

California 1797 1499 ⫺16.6 2042 1633 ⫺20.1 2177 2138 ⫺1.8

Colorado 68 44 ⫺35.0 124 92 ⫺26.4 119 102 ⫺14.5

Connecticut 108 85 ⫺21.2 107 99 ⫺7.1 141 47 ⫺66.6

Delaware 21 15 ⫺29.5 29 22 ⫺22.7 41 42 1.3

District of Columbia 46 42 ⫺9.3 48 43 ⫺11.2 76 57 ⫺24.3

Florida 399 212 ⫺46.9 715 488 ⫺31.7 1052 779 ⫺25.9

Georgia 254 150 ⫺40.8 422 360 ⫺14.7 629 656 4.2

Hawaii 46 32 ⫺28.9 53 63 16.9 NA NA NA

Idaho 16 3 ⫺80.8 40 33 ⫺18.3 64 56 ⫺12.3

Illinois 451 383 ⫺15.2 545 483 ⫺11.3 710 635 ⫺10.6

Indiana 101 79 ⫺21.9 188 156 ⫺16.9 300 235 ⫺22.0

Iowa 59 46 ⫺22.2 84 65 ⫺22.5 144 126 ⫺12.3

Kansas 47 26 ⫺43.4 87 53 ⫺39.5 127 114 ⫺10.2

Kentucky 125 90 ⫺27.8 213 177 ⫺16.7 281 277 ⫺1.5

Louisiana 142 127 ⫺10.7 362 287 ⫺20.6 370 410 10.6

Maine 35 27 ⫺21.8 50 43 ⫺14.9 70 71 2.4

Maryland 136 90 ⫺34.3 200 170 ⫺15.0 179 186 3.9

Massachusetts 166 120 ⫺27.5 190 166 ⫺12.4 306 297 ⫺2.9

Michigan 348 250 ⫺28.2 451 404 ⫺10.4 508 472 ⫺7.1

Minnesota 117 98 ⫺16.3 152 108 ⫺28.7 226 163 ⫺28.0

Mississippi 97 47 ⫺51.5 220 174 ⫺20.9 242 192 ⫺20.9

Missouri 154 120 ⫺22.1 276 209 ⫺24.5 297 227 ⫺23.6

Montana 21 14 ⫺34.5 37 30 ⫺18.8 37 41 13.0

Nebraska 27* 27* 2.8 52 47 ⫺9.2 49 110 126.2

Nevada 26 20 ⫺24.7 52 37 ⫺27.7 55 50 ⫺9.2

New Hampshire 17 10 ⫺39.0 27 21 ⫺21.2 51 51 ⫺.7

New Jersey 201 153 ⫺23.9 282 218 ⫺22.7 299 154 ⫺48.6

New Mexico 67 44 ⫺34.4 125 95 ⫺23.7 199 201 .9

New York 799 646 ⫺19.1 965 816 ⫺15.4 1373 1391 1.3

North Carolina 191 135 ⫺29.3 304 264 ⫺13.2 548 569 3.8

North Dakota 9 6 ⫺29.5 17 16 ⫺5.5 25 26 4.2

Ohio 370 254 ⫺31.2 488 336 ⫺31.2 750 625 ⫺16.6

Oklahoma 73 45 ⫺38.9 163 141 ⫺13.7 172 NA NA

Oregon 54 34 ⫺37.1 131 101 ⫺22.6 110 213 93.3

Pennsylvania 368 272 ⫺26.1 513 420 ⫺18.0 504 420 ⫺16.6

Rhode Island 39 30 ⫺23.5 48 42 ⫺13.1 52 41 ⫺22.1

South Carolina 90 50 ⫺44.6 190 176 ⫺7.6 236 244 3.4

South Dakota 12 8 ⫺35.2 24 25 .6 41 39 ⫺2.9

Tennesee 182 104 ⫺42.6 284 261 ⫺8.0 454 588 29.5

Texas 495 284 ⫺42.5 1320 924 ⫺30.0 1474 1469 ⫺.3

Utah 27 22 ⫺18.7 58 53 ⫺8.7 81 73 ⫺9.7

Vermont 16 12 ⫺20.1 27 19 ⫺28.9 51 52 2.1

Virginia 112 74 ⫺33.7 261 207 ⫺20.7 318 296 ⫺6.7

Washington 180 141 ⫺21.8 247 179 ⫺27.5 306 301 ⫺1.6

West Virginia 64 34 ⫺46.9 123 110 ⫺10.7 181 177 ⫺2.1

Wisconsin 121 33 ⫺72.6 159 110 ⫺30.6 105 126 20.1

Wyoming 8 2 ⫺74.7 17 13 ⫺30.1 27 26 ⫺4.0

Total United States 8570 6183 ⫺27.9 13 190 10 519 ⫺20.2 16 281 15 258 ⫺6.3

FY indicates fiscal year; NA, not available.

POTENTIAL HEALTH EFFECTS OF WELFARE REFORM

Although there are many potential ways welfare reform can influence the well-being of poor children and their families, we consider the principal path-ways to be: changes in family resources, influences on parental supervision, and alterations in access to health care.

Changes in Family Resources and Income

Although PRWORA has many complex compo-nents, its primary impact will depend on whether it serves to increase or decrease resources for families who leave and those who remain on welfare. Despite the centrality of this issue, there are limited data on the long-term economic status of families after they leave the welfare rolls. Recent studies of different states have shown that one half to two thirds of people who left welfare were employed when sur-veyed 3 to 12 months later.34 –38However, all of these

welfare leaver studies are limited by relatively short follow-up periods. These studies also indicate that although many former recipients are working, their earnings do not raise them above the poverty level, because most are employed in low-wage, entry-level work.34,41

This concentration in low-wage work is consistent with the evidence that families who leave welfare for work face significant barriers to employment, includ-ing inadequate education, traininclud-ing, and previous work experience.42– 44Former recipients also tend to

be young single parents with young children.34Child

health is often cited as a barrier to parental employ-ment among welfare recipients.42– 44This is not

sur-prising because recent studies indicate that children of welfare recipients have a higher burden of illness than do other poor children—20% to 40% of families receiving AFDC had children with chronic illnesses, compared with 10% of all poor families.45– 47

Because it may be difficult for women with chron-ically ill children to meet the new work require-ments, they will be more vulnerable to sanctions or benefit terminations for noncompliance. Although states can provide exemptions to work requirements because of child illness, many base such exemptions on strict criteria such as SSI disability designation. Such exemptions, however, will not affect mothers of chronically ill children who have significant health needs and require parental participation in their medical care, but who may not meet SSI disability standards. For example, chronically ill children with respiratory diseases have 3 times the number of phy-sician visits and 4 times the rate of hospitalizations of healthy children.47

Although the dramatic declines in TANF rolls may well reflect improved social conditions for some fam-ilies previously reliant on public assistance, a portion of poor families will likely experience significant hardship, particularly during difficult economic times. Taken together, the barriers to employment, sanctions, and the termination of benefits outlined above will cause some families to experience declines in available income. There is much evidence to

indi-cate that decreases in family resources, including food stamps, resulting from welfare policies have the potential to cause predictable and substantial ad-verse child health effects.48 –55

The impact of the substantial declines in food stamp participation on the nutritional status of poor children must also be considered. Poor children are 5 times more likely to experience food insecurity and hunger, and they have significantly lower intake of calories, iron, folate, and other nutrients, compared with nonpoor children.56,57Undernutrition is

associ-ated with numerous adverse health outcomes, in-cluding poor growth, iron deficiency, lead poisoning, and impaired cognitive development.53,55,57–59 In

contrast, food stamp use is associated with a lower risk of inadequate food intake and improved nutri-tional status.

Changes in Parental Supervision: Work Flexibility and Day Care

Parental work requirements included in welfare reform raise important questions regarding childcare arrangements while parents are working. Inadequate or substandard childcare poses a variety of risks, including injuries, communicable diseases, and non-compliance with prescribed medical regimens.60 In

the case of chronically ill children, flexibility in pa-rental employment as well as appropriate child care are essential to maintaining reasonable health. For example, children with asthma who adhere to their medical regimens are more likely to have their dis-ease well-controlled.61– 63 Depending on the age of

the child, parental time and supervision are needed for the recognition of symptoms, administration of appropriate treatments, and attendance at medical visits.64 – 67

Former welfare recipients are unlikely to find jobs that provide the flexibility needed to care for a chron-ically ill child, because most find low-wage work in industries characterized by limited parental benefits or leave policies.41,68National data suggest that

em-ployed poor mothers and mothers of chronically ill children have less sick leave than do other mothers.60

In particular, a substantial proportion of former wel-fare recipients lacked sick leave or vacation leave or a flexible schedule that might allow them to care for a sick child.41,46 This disparity between the amount

of illness poor families experience and the degree of work flexibility available to them suggests that these parents will be faced with the difficult decision of what to do when their child is sick or needs to go to the doctor and they are unable to take time off from work.

The problem of inadequate day care for current and former TANF recipients was underscored by recent data suggesting a shortage of affordable day care, especially for infants and toddlers.69,70The gap

in available care is particularly striking for poor fam-ilies who work nonday schedules because most child care providers are unavailable during these off hours.69 –71 For many families, this means that they

families, a factor that increases the risk of deleterious child health and developmental outcomes.71–73

PRWORA provided additional funding for child care subsidies, which are critical in assisting former recip-ients to obtain affordable quality day care.69

How-ever, most states are unable to provide child care subsidies to all families who meet the eligibility cri-teria, resulting in waiting lists and copayments to restrict access to limited child care funds.69,74

Changes in Access to Health Care

The primary means of providing health insurance to children on welfare has been the Medicaid pro-gram. The reduction in Medicaid enrollment since the passage of PRWORA raises concerns about un-insured children in families leaving welfare. Despite provisions for continued coverage, several studies provide consistent evidence that up to one half of children in the examined states were not enrolled in Medicaid 6 months after leaving welfare and that there was limited use of available transitional Med-icaid coverage.34,36,75,76Medicaid dropout of eligible

children is at least partly caused by administrative barriers and the lack of coordination between Med-icaid and welfare agencies.19,25,28 Overall, 40% of

former recipients and 25% of their children were uninsured.75 Recipients uninsured by Medicaid are

unlikely to have employer-based private insurance because the proportion who found jobs providing such insurance varies considerably, from 10% to 60% and even those who have access to employer insur-ance may not be able to afford the cost of the premi-ums.27,28,36 The fact that a substantial proportion of

children who leave welfare become uninsured is of concern because research has repeatedly shown that poor children without health insurance experience impaired access to health care. They are less likely to have a regular source of care and are more likely to have difficulty obtaining prescription medications and to delay seeking care because of cost con-cerns.77,78 Moreover, uninsured children with a

chronic illness are more likely to have had no phy-sician visit in the previous 12 months.79,80Thus,

wel-fare policies that unintentionally result in higher rates of uninsured children can be expected to result in a variety of adverse health outcomes and a grow-ing burden on the financial well-begrow-ing of clinical practices and institutions that care for poor children in the United States.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CHILD HEALTH POLICY AND CLINICAL PRACTICE

The nature and scale of welfare reform will create new challenges and opportunities for clinicians who care for poor children in the United States. The per-sistence of continued high rates of uninsurance in the face of a decline in Medicaid enrollment represents a serious barrier to improved child health and will generate new financial burdens for clinical practices and institutions serving poor families. The extent to which uninsurance remains a problem depends on how successful individual states are in enrolling eli-gible children in their Medicaid and SCHIP pro-grams. Early evidence suggests that there is

consid-erable variation in how effective states have been in their outreach efforts and in overcoming important administrative barriers to enrollment, such as fre-quent eligibility redeterminations and complicated applications.25,28,81In addition, hospitals and clinics

that are confronted with higher rates of uncompen-sated care because of uninsured children will have a strong financial incentive to address this problem.

From a policy perspective, there is an urgent need to understand what portion of the declines noted in Medicaid, food stamps, and SSI is attributable to economic growth or welfare policies. This will be key in determining whether more attention should be focused on revising inherently problematic program policies or on modifying policies in preparation for an economic slowdown. The pediatric community could help to raise public awareness of these trends and help to seek policy-based remedies, including those recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics.82Although the data on enrollment trends

in these programs are from a relatively short time frame, these are the only data currently available. Better and more timely information on child health and well-being would contribute to a more informed debate regarding PRWORA as it approaches its re-authorization in 2002. Policy makers must consider the prospect that if some families are unable to leave welfare and escape poverty during the current ro-bust economy, it is likely that the potential for ad-verse consequences will increase during an economic downturn.8

As enrollment efforts proceed, greater attention should be paid to population groups that are lagging behind. One such group is US-born children of im-migrants who avoid applying for Medicaid because of fear that Medicaid receipt will be used as evidence of being a public charge and will adversely affect their application for citizenship.28 Clinicians will

need to maintain a heightened awareness of the problem of uninsured children and institute vigor-ous outreach efforts, such as those suggested by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Covering Kids initiative sponsored by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Insure Kids Now campaign co-sponsored by the Department of Health and Human Services and the National Governor’s Associa-tion.14,83,84

and maintaining health insurance for children with special health care needs. To provide optimal assis-tance for their patients, clinicians caring for poor children should have a working knowledge of local welfare policies and should develop linkages with social service agencies and community-based orga-nizations. For example, one urban pediatric clinic has instituted a model of routine screening regarding health insurance, food availability, and welfare re-ceipt followed by a referral and follow-up process to assist families in obtaining needed services.85

The clinical arena could also serve as an essential source of empirical data on the impact of welfare reform on children. Clinical cohorts, particularly those focused on children with chronic illness, could provide information on the health of children who undergo changes in their welfare status. Health care providers could also play an important role in iden-tifying families who fall more deeply into poverty under welfare reform provisions even if the overall experience of the entire disenrolled population seems positive. Such narrative-based medicine can use the power of patients’ stories to set research and policy agendas.86,87 Practitioners can contribute to

welfare reform policy debates by providing clinically relevant, qualitative insights regarding sentinel cases to effectively supplement or trigger larger, quantita-tive evaluations and epidemiologic studies. Al-though we await forthcoming data from sources such as the Urban Institute’s National Survey of American Families as well as the Census Bureau’s Survey of Program Dynamics, the availability of clin-ically applicable data on child health in these studies will be limited.88,89

Clinicians are in a position to make significant contributions to promoting the health and well-being of children during the implementation of welfare reform by using the experience of clinical practice and applied research to inform the development of child health policy. Because control over welfare reg-ulations has fallen increasingly to the states, health care providers are in a better position to influence local policy through their advocacy efforts. Through informed advocacy, the pediatric community can en-sure that the health of children is included in the assessment of the effects of social welfare policy. Through our clinical experiences, we can ensure that the discussion of welfare reform is informed by a deeper understanding of the human experience that the numbers imply.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by funding from the Ford Foundation, the Peabody Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the William T. Grant Foundation, and the Alpert Endowment for the Children of the City.

We thank Howard Bauchner, MD, who reviewed previous drafts of this article, and Michelle Villarta and Giliane Joseph, who assisted in the preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Administration for Children and Families.Characteristics and Financial Circumstances of TANF Recipients, Fiscal Year 1998. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for

Chil-dren and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1999 2. Administration for Children and Families.Characteristics and Financial Circumstances of AFDC Recipients, Fiscal Year 1996. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Chil-dren and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1997 3. Health Care Financing Administration. Medicaid recipients by basis of eligibility and by region and state: fiscal year 1996. Available at: http:// www.hcfa.gov/medicaid/mstats.htm. Accessed April 14, 2000 4. US General Accounting Office.Food Stamp Program: Various Factors Have

Led to Declining Participation.Washington, DC: US General Accounting Office; 1999. GAO/RCED-99-185

5. US Department of Agriculture.Who Is Leaving the Food Stamp Program? An Analysis of Caseload Changes From 1994 to 1997. Washington, DC: Office of Analysis, Nutrition and Evaluation, Food and Nutrition Ser-vice, US Department of Agriculture; 1999

6. US Department of Agriculture.Characteristics of Food Stamp Households: Fiscal Year 1998. Washington, DC: Office of Analysis, Nutrition and Evaluation, Food and Nutrition Service, US Department of Agriculture; 1999

7. Ku L, Garrett B.How Welfare Reform and Economic Factors Affected Med-icaid Participation: 1984 –1996. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2000. Assessing the New Federalism, 00-01

8. Danziger SH, ed.Economic Conditions and Welfare Reform. Kalamazoo, MI: WE Upjohn Institute; 1999

9. Council of Economic Advisors. The Effects of Welfare Policy and the Economic Expansion of Welfare Caseloads: An Update. Washington, DC: The White House, Office of the Press Secretary; 1999

10. Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services. Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: se-lected provisions of state plans. Available at: http://www.acf.dhhs. gov/programs/ofa. Accessed April 14, 2000

11. Administration for Children and Families. Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Program (TANF): Final Rule. Washington, DC: US Depart-ment of Health and Human Services; 1999. Federal Register, vol. 64, no. 69

12.Minnefield v McIntire, Civil Action 99-3349-G (Suffolk Superior Court 1999)

13. Gallagher LJ, Gallagher M, Perese K, Schreiber S, Watson K.One Year After Federal Welfare Reform: A Description of State Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Decisions as of October 1997. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 1998. Assessing the New Federalism, Occasional Paper 6

14. Health Care Financing Administration. The State Children’s Health Insurance Program annual enrollment report: October 1, 1998 –September 30, 1999. Available at: http://www.hcfa.gov/init/ children.htm. Accessed April 14, 2000

15. US House of Representatives, Committee on Agriculture.Declines in Food Stamp and Welfare Participation: Is There a Connection?Hearings before the Department Operations, Oversight, Nutrition and Forestry Subcommittee of the Committee on Agriculture; August 1999; Wash-ington, DC

16. Perrin J. The implications of welfare reform in developmental and behavioral pediatrics.Dev Behav Pediatr. 1997;18:264 –266

17. Stapleton DC, Fishman ME, Livermore GA, Wittenburg D, Tucker A, Scrivner S.Policy Evaluation of the Overall Effects of Welfare Reform on SSA Programs. Washington, DC: The Lewin Group, Inc; 1999

18. Rogowski J, Karoly L, Klerman J, et al.Background and Study Design Report for Policy Evaluation of the Effect of the 1996 Welfare Reform Legis-lation on SSI Benefits for Disabled Children. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 1998. DRU-1808-SSA

19. Chavkin W, Romero D, Wise PH. State welfare reform policies and declines in health insurance.Am J Public Health. 2000;90:900 –908 20. US Conference of Mayors. Status report on hunger and homelessness in

America’s cities: 1999. Available at: http://www.usmayors.org. Ac-cessed April 25, 2000

21. US Bureau of the Census. Health insurance coverage: 1998. Available at: http://www.census.gov/hhes/hlthins/hlthin98/hi98t5.html. Ac-cessed April 14, 2000

22. US Bureau of the Census.Poverty in the United States. Washington, DC: US Bureau of the Census; 1998:60 –207

23. Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services. Change in TANF caseloads. Available at: http:// www.acf.dhhs.gov/stats/caseload.htm. Accessed April 14, 2000 24. Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health

and Human Services. Change in welfare caseload since enactment of new welfare law. Available at: http://www.acf.dhhs.gov/news/stats/ aug-sept.htm. Accessed September 18, 1999

Enroll-ment Problems Persist. Findings From a Five-State Study. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 1999. Assessing the New Federalism, Occasional Paper 30

26. Ellis ER, Smith VK.Medicaid Enrollment in 21 States. Washington, DC: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2000. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured

27. Ellwood M, Ku L. Welfare and immigration reforms: unintended side effects for Medicaid.Health Aff. 1998;17:137–151

28. US General Accounting Office.Medicaid Enrollment: Amid Declines, State Efforts to Ensure Coverage After Welfare Reform Vary. Washington, DC: US General Accounting Office; 1999. GAO/HEH-99-163

29. Guyer J, Broaddus M, Cochran M.Missed Opportunities: Declining Med-icaid Enrollment Undermines the Nation’s Progress in Insuring Low-Income Children. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; 1999 30. Pulos V.One Step Forward, One Step Back: Children’s Health Coverage after CHIP and Welfare Reform. Washington, DC: Families USA Foundation; 1999

31. Selden TM, Banthin JS, Cohen JW. Medicaid’s problem children: eligible but not enrolled.Health Aff. 1998;17:192–200

32. Selden TM, Banthin JS, Cohen JW. Waiting in the wings: eligibility and enrollment in the State Children’s Health Insurance Program.Health Aff. 1999;18:126 –133

33. Smith VK.Enrollment Increases in State CHIP Programs: December 1998 to June 1999. Washington, DC: Health Management Associates; 1999 34. Loprest P.Families Who Left Welfare: Who Are They and How Are They

Doing?Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 1999:99 –102

35. Prendergast M, Nagle G, Goodro B.How Are They Doing?: A Longitudinal Study of Households Leaving Welfare Under Massachusetts Reform. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Department of Transitional Assistance; 1999 36. National Governors’ Association, National Conference of State

Legisla-tures, and American Public Welfare Association. Tracking recipients after they leave welfare: summaries of state follow-up studies. Available at: http://www.nga.org/welfare/statefollowup.html. Accessed April 14, 2000

37. Tweedie J, Reichert D, O’Connor M. Tracking recipients after they leave welfare. Available at: www.ncsl.org/statefed/welfare/leavers.html. Accessed April 14, 2000

38. Department of Social and Health Services.Washington’s TANF Single Parent Families After Welfare. Olympia, WA: Washington State Division of Program Research and Evaluation, Department of Social and Health Services; 1999

39. US Department of Agriculture.Distribution of Children Receiving Food Stamps by State, Fiscal Years 1996 –1998. Washington, DC: Office of Analysis, Nutrition and Evaluation, Food and Nutrition Service, US Department of Agriculture; 1999

40. Pickett C.Children Receiving SSI: December 1999. Baltimore, MD: Office of Research, Evaluation and Statistics, Division of SSI Statistics and Analysis, and Social Security Administration; 1999

41. Parrott S.Welfare Recipients Who Find Jobs: What Do We Know About Their Employment and Earnings? Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; 1998

42. Olson K, Pavetti L.Personal and Family Challenges to the Successful Tran-sition From Welfare to Work. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 1997 43. Pavetti L.How Much More Can Welfare Mothers Work?Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin-Madison, Institute for Research on Poverty; 1999. No. 20

44. Danziger S, Corcoran M, Danziger S, et al. Barriers to Work Among Welfare Recipients. Madison, WI: Institute for Research on Poverty; 1999. No. 20

45. The Urban Institute. Profile of disability among AFDC families. Avail-able at: http://www.urban.org/periodc/26 2/prr26 2d.htm. Ac-cessed July 15, 1997

46. Heymann SJ, Earle A. The impact of welfare reform on parents’ ability to care for their children’s health.Am J Public Health. 1999;89:502–505 47. Newacheck PW, Halfon N. Prevalence and impact of disabling chronic

conditions in childhood.Am J Public Health. 1998;88:610 – 617 48. Wise PH, Meyer A. Poverty and child health.Pediatr Clin North Am.

1988;35:1169 –1186

49. Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ. The effects of poverty on children.Future Child. 1997;7:55–71

50. Askew GL, Wise PH. The neighborhood: poverty, affluence, geographic mobility, and violence. In: Levine M, Carey W, Crocker A, eds. Devel-opmental-Behavioral Pediatrics. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Company; 1999:177–187

51. Halfon N, Newacheck PW. Childhood asthma and poverty: differential impacts and utilization of health services.Pediatrics. 1993;91:56 – 61 52. Weitzman M, Gortmaker S, Sobol A. Racial, social, and environmental

risks for childhood asthma.Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:1189 –1194

53. Frank DA, Zeisel SH. Failure to thrive.Pediatr Clin North Am. 1988;35: 1187–1206

54. Parker S, Greer S, Zuckerman B. Double jeopardy: the impact of poverty on early child development.Pediatr Clin North Am. 1988;35:1227–1240 55. Korenman S, Miller JE, Sjaastad JE. Long-term poverty and child

de-velopment in the United States: results from the NLSY.Child Youth Serv Rev. 1995;17:127–155

56. Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics.America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being. Washington, DC: Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, US Government Printing Office; 1998

57. Cook JT, Martin KS.Differences in Nutrient Adequacy Among Poor and Non-Poor Children. Medford, MA: Center on Hunger, Poverty and Nu-trition Policy, Tufts University School of NuNu-trition; 1995

58. Lewitt EM, Kerrebrock N. Child indicators: population-based growth stunting.Future Child. 1997;7:149 –156

59. Center on Hunger, Poverty and Nutrition Policy.Statement on the Link Between Nutrition and Cognitive Development in Children. Medford, MA: Center on Hunger, Poverty and Nutrition Policy, Tufts University School of Nutrition; 1995

60. Heymann SJ, Earle A, Egleston B. Parental availability for the care of sick children.Pediatrics. 1996;98:226 –230

61. Fireman P, Friday GA, Gira C, Vierthaler WA, Micheals L. Teaching self-management skills to asthmatic children and their parents in an ambulatory care setting.Pediatrics. 1981;68:341–348

62. Milgom H, Bender B, Ackerson L, Bowry P, Smith B, Rand C. Noncom-pliance and treatment failure in children with asthma.J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;98:1051–1057

63. Milgom H, Bender B. Nonadherence to asthma treatment and failure of therapy.Curr Opin Pediatr. 1997;9:590 –595

64. Gibson NA, Ferguson AE, Aitchison TC, Paton JY. Compliance with inhaled asthma medication in preschool children. Thorax. 1995;50: 1274 –1279

65. Ferguson AE, Gibson NA, Aitchison TC, Paton JY. Measured broncho-dilator use in preschool children with asthma. Br Med J. 1995;310: 1161–1164

66. Leickly FE, Wade SL, Crain E, Kruszon-Moran D, Wright EC, Evans R III. Self-reported adherence, management behavior, and barriers to care after an emergency department visit by inner city children with asthma. Pediatrics. 1998;101:917–918

67. Ordonez GA, Phelan PD, Olinsky A, Robertson CF. Preventable factors in hospital admissions for asthma.Arch Dis Child. 1998;78:143–147 68. Cancian M, Haveman R, Kaplan T, Meyer D, Wolfe B.Work, Earnings,

and Well-Being After Welfare: What Do We Know?Madison, WI: Univer-sity of Wisconsin-Madison, Institute for Research on Poverty; 1999. No. 20

69. US General Accounting Office.Child Care: States’ Efforts to Expand Pro-grams Under Welfare Reform. Washington, DC: US General Accounting Office; 1998. GAO/T-HEHS-98-148

70. US General Accounting Office.Welfare Reform: Implications of Increased Work Participation for Child Care. Washington, DC: US General Account-ing Office; 1997. GAO/HEHS-97-75

71. Hofferth SL. Child care in the United States today.Future Child. 1999; 6:41– 61

72. Phillips DA, Voran M, Kisker E, Howes C, Whitebook M. Child care for children in poverty: opportunity or inequity? Child Dev. 1994;65: 472– 492

73. Helburn SW, Howes C. Child care cost and quality.Future Child. 1999; 6:62– 82

74. Piecyk JB, Collins A, Kreader JL.A Report of the NCCP Child Care Research Partnership: Patterns and Growth of Child Care Voucher Use by Families Connected to Cash Assistance in Illinois and Maryland. New York, NY: National Center for Children in Poverty; 1999

75. Garrett B, Holahan J. Health insurance coverage after welfare.Health Aff. 2000;19:175–184

76. US General Accounting Office.Welfare Reform: Information on Former Recipients’ Status. Washington, DC: US General Accounting Office; 1999. GAO/HEHS-99-48

77. Simpson G, Bloom B, Cohen RA, Parsons PE. Access to health care: children.Vital Health Stat. 1997;10:1– 46

78. Newacheck PW, Hughes DC, Stoddard JJ. Children’s access to primary care: differences by race, income, and insurance status.Pediatrics. 1996; 97:26 –32

79. Holl JL, Szilagyi PG, Rodewald LE, Byrd RS, Weitzman ML. Profile of uninsured children in the United States.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995; 149:398 – 406

health care for children with special health care needs.Pediatrics. 2000; 105:760 –766

81. Perry M, Kannel S, Valdez RB, Chang C.Medicaid and Children: Over-coming Barriers to Enrollment. Findings From a National Survey. Washing-ton, DC: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2000. Kaiser Commis-sion on Medicaid and the Uninsured

82. American Academy of Pediatrics. The American Academy of Pediatrics’ proposal to insure America’s children. Available at: http://www.aap. org/advocacy/washing/web101199.htm. Accessed November 9, 1999 83. American Academy of Pediatrics. SCHIP outreach. Available at: http://

www.aap.org/advocacy/washing/schip.html. Accessed April 14, 2000 84. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. About covering kids. Avail-able at: http://www.coveringkids.org/about.html. Accessed April

14, 2000

85. Lawton E, Leiter K, Todd J, Smith L. Welfare reform: advocacy and intervention in the health care setting. Public Health Rep. 1999;114: 540 –549

86. Greenhalgh T. Narrative based medicine: narrative based medicine in an evidence based world.Br Med J. 1999;318:323–325

87. Greenhalgh T, Hurwitz B. Narrative based medicine: why study narra-tive?Br Med J. 1999;318:48 –50

88. US Bureau of the Census. Overview of the survey of program dynamics. Available at: http://www.sipp.census.gov/spd/overvu2.htm. Ac-cessed March 23, 1999

89. The Urban Institute.Snapshots of America’s Families. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2000. Assessing the New Federalism

A COUGH SYRUP INGREDIENT IS A POPULAR DRUG

School officials weren’t sure what was going on, but concerned students had an idea. They said their friends might have taken DXM, or dextromethorphan, a drug commonly found in cough medicine. “We went into the boy’s room and found a white, powdered substance,” says Susan James, director of communications for Peddie School, a preparatory school in Hightstown, New Jersey. “Then we down-loaded information on the drug from the Internet and took it with us to the hospital.”

James says getting the information this quickly might have helped emergency medical workers treat 4 students, one of whom was briefly in intensive care. But ready access to the Internet also partially caused the problem. One of the 4 had purchased the drug from an Internet site—and had it shipped directly to the school . . . Chugging cough syrup— or “roboing” as it is often called, after the over-the-counter medication Robitussin— has been around for decades, but experts believe that use of DXM, in syrup or powder form, is on the rise. That comes not only from online availability but also because DXM is considered a poor man’s version of the popular drug Ecstasy. . .

Schultz S.US News & World Report.June 5, 2000

DOI: 10.1542/peds.106.5.1117

2000;106;1117

Pediatrics

Zuckerman

Lauren A. Smith, Paul H. Wise, Wendy Chavkin, Diana Romero and Barry

Clinical Practice and Policy

Implications of Welfare Reform for Child Health: Emerging Challenges for

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/106/5/1117

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/106/5/1117#BIBL

This article cites 34 articles, 14 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/child_health_financing

Child Health Financing

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/advocacy_sub

Advocacy

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/for_your_benefit

For Your Benefit

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.106.5.1117

2000;106;1117

Pediatrics

Zuckerman

Lauren A. Smith, Paul H. Wise, Wendy Chavkin, Diana Romero and Barry

Clinical Practice and Policy

Implications of Welfare Reform for Child Health: Emerging Challenges for

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/106/5/1117

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.