Barriers and Stigma Experienced

by Gay Fathers and Their Children

Ellen C. Perrin, MD, a, b Sean M. Hurley, PhD, c Kathryn Mattern, BA, a Lila Flavin, BA, d Ellen E. Pinderhughes, PhDbBACKGROUND: Gay men have become fathers in the context of a heterosexual relationship, by adoption, by donating sperm to 1 or 2 lesbian women and subsequently sharing parenting responsibilities, and/or by engaging the services of a surrogate pregnancy carrier. Despite legal, medical, and social advances, gay fathers and their children continue to experience stigma and avoid situations because of fear of stigma. Increasing evidence reveals that stigma is associated with reduced well-being of children and adults, including psychiatric symptoms and suicidality.

METHODS: Men throughout the United States who identified as gay and fathers completed an online survey. Dissemination of the survey was enhanced via a “snowball” method, yielding 732 complete responses from 47 states. The survey asked how the respondent had become a father, whether he had encountered barriers, and whether he and his child(ren) had experienced stigma in various social contexts.

RESULTS: Gay men are increasingly becoming fathers via adoption and with assistance of an unrelated pregnancy carrier. Their pathways to fatherhood vary with socioeconomic class and the extent of legal protections in their state. Respondents reported barriers to becoming a father and stigma associated with fatherhood in multiple social contexts, most often in religious institutions. Fewer barriers and less stigma were experienced by fathers living in states with more legal protections.

CONCLUSIONS: Despite growing acceptance of parenting by same-gender adults, barriers and stigma persist. States’ legal and social protections for lesbian and gay individuals and families appear to be effective in reducing experiences of stigma for gay fathers.

abstract

aDivision of Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics, Floating Hospital for Children, Tufts Medical Center, Boston,

Massachusetts; bDepartment of Child Study and Human Development and dSchool of Medicine, Tufts University,

Boston, Massachusetts; and cDepartment of Leadership and Developmental Sciences, University of Vermont,

Burlington, Vermont

Drs Perrin and Pinderhughes conceptualized and designed the study, created the survey instrument, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Hurley designed the analytic approach, conducted the analyses, and created the figures; Ms Mattern assisted in creating the survey instrument, supervised the data collection, and managed the data; Ms Flavin assisted in editing and preparing the manuscript for submission; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

DOI: https:// doi. org/ 10. 1542/ peds. 2018- 0683 Accepted for publication Oct 25, 2018

Address correspondence to Ellen C. Perrin, MD, Division of Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics, Floating Hospital for Children, Tufts Medical Center, 800 Washington St, Boston, MA 02111. E-mail: eperrin@tuftsmedicalcenter.org

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275). Copyright © 2019 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: Gay men are increasingly becoming fathers in various ways. Barriers and stigma have been described in their experiences as fathers in their families, in jobs and children’s schools, and in health care settings. WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: The frequency and pathways by which gay men are becoming fathers is changing, but barriers and stigma remain. Structural stigma reflected in state laws and the beliefs of religious communities affect gay fathers’ experiences in multiple social contexts.

Social attitudes about gay and lesbian parenting have changed dramatically. Heterosexual identity is no longer considered a prerequisite for the formation of intimate partnerships, marriage, or even parenthood. Many court cases over the past decade have been resolved in favor of same-gender parents’ rights to legal parenthood. The 2013 US Supreme Court’s legalization of full rights to marriage for same-gender partners provided full legitimacy to families created by lesbian and gay couples and recognized that their children would be beneficiaries of the sanctioned legal status of their parents. Social science research has documented the well-being of children raised by same-gender parents, 1, 2 and many professional

associations that address parenting have endorsed confidence and optimism about gay or lesbian parents raising children, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, Academic Pediatric Association, American Medical Association, and American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. The American Academy of Pediatrics noted that

“… children’s well-being is affected much more by their relationships with their parents, their parents’

sense of competence and security, and the presence of social and economic support for the family than by the gender or the sexual orientation of their parents.”3

As a result of these developments, over half of gay teenagers expect to become fathers, 4, 5 and their possible

pathways to parenthood have expanded enormously.6 Previously,

most gay men became fathers in the context of a heterosexual marriage; some knew that they were gay and saw marriage as the only route to parenthood; others recognized and acknowledged their homosexuality later.7 Occasionally,

gay men partnered with single or lesbian women, donating sperm and working out unique arrangements for

coparenting.8 Same-gender couples

have been increasingly invited and even encouraged to become foster parents and/or to adopt children through domestic and international agencies.9–11 More recently, new

reproductive technologies have allowed gay men to provide sperm to a woman who would carry a pregnancy for them, a surrogate carrier.12

Thus, gay fathers have risen in numbers and visibility over the last decade, challenging assumptions that embracing a gay identity meant forgoing the possibility of parenthood. Most national surveys do not include questions about parental sexual orientation, limiting large-scale research regarding these families. The 2010 census reported 377903 male-couple households in the United States, of which 11% are raising a biological, step, or adopted child <18 years old.13 An unknown

number of gay men who are raising children without a cohabiting partner are not counted in the census.

Nevertheless, gay men report suspicion and criticism for their decision to be parents from gay friends who have not chosen parenthood, barriers in the adoption process, and isolation in their parental role.14, 15 Gay men

who became parents while in a heterosexual relationship may face difficulties maintaining custody or obtaining legal parenting rights for a new spouse.14 Adoption and

surrogacy options are also limited by their high cost.16 Gay fathers have to

contend with the still-prevalent belief that children need a mother to thrive and stereotypes associated with gay men as frivolous, unstable, and unfit parents.15 A recent study revealed

that although gay fathers did not differ from heterosexual fathers in the strength and quality of their relationships, feelings of rejection and having to justify themselves as parents affected fathers’ feelings of competence as parents.17 Moreover,

children with gay fathers must learn to cope with the pressure of being different from their peers in both their biologic origins and family structure.

Our objective in this study was to discover whether gay men continue to encounter barriers in becoming fathers and stigma in various contexts and to examine associations between these experiences and legal and social structures that surround these families.

We report on a survey of gay men from 47 states who became parents through diverse pathways. Respondents provided information about the pathways they used to become fathers, barriers they faced in becoming parents, and their experiences of stigmatization. We consider individuals’ experiences of “active stigma” and avoidance of desirable activities on the basis of “anticipated stigma.”18 We

also consider “structural stigma”: beliefs, policies, and laws that either intentionally or unintentionally limit the well-being of particular individuals.19 We use each state’s

laws and policies and the stated beliefs of religious institutions to reflect elements of structural stigma.

METHODS

Survey Instrument

We created an anonymous online survey instrument that required

∼30 minutes to complete and was approved by the Tufts University Institutional Review Board. Participants gained access to the survey after self-identifying as a gay father, >18 years old, living in the United States, and giving consent. Participants were asked to send the survey link to other gay fathers and encourage them to participate. Sections of the questionnaire included the following:

2. the method(s) by which the child(ren) joined the family; 3. whether the respondent had faced

barriers in accessing pathways to parenthood; and

4. whether respondents had been

“made to feel uncomfortable, excluded, shamed, hurt, or unwelcome” in specific social contexts because of being/having a gay father (active stigma), or had “avoided various situations because of worry about people’s judgments” (anticipated stigma). Fathers of children between 5 and 18 years old were asked similarly about their children’s experiences of stigma. Table 2 lists the social contexts specified (eg, family, friends, school, religious gatherings, etc). Each respondent thus received 4 scores: the sum of social contexts in which he reported active stigma, the sum of contexts that he reported avoiding, and parallel categories for his child(ren).

Procedures

Recruitment of Sample

We distributed a link to the survey through targeted Facebook advertising, an advertisement in

Gay Parent Magazine, Twitter, Meetup groups, and direct contacts with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) parenting groups, advocacy organizations, LGBT community and cultural centers, surrogacy and adoption agencies, and church groups

throughout the United States. Groups were asked to share the survey link with their membership through their listservs or newsletters and/or by physically posting an advertisement. We contacted >100 organizations throughout 50 states and staffed a table at the Family Equality Council’s Gay Parents’ Weekend in Provincetown, Massachusetts.

Social Climate

To understand the influence of the social environment on gay fathers and their children, we used the

“equality ratings” created by the Movement Advancement Project (http:// www. lgbtmap. org/ state- policy- tally- faq) based on each state’s laws for protection of LGBT families (eg, laws regarding adoption and foster care by lesbians and gay men, the availability of legal domestic partnerships, civil unions, and civil marriage, regulations about bullying in schools, etc). Each state is rated between 0 and 3; higher numbers reflect more legal protections offered by the state. We used rankings of specific religious groups reported by Hatzenbuehler et al, 20 which were

based on the explicit beliefs of each religion regarding homosexuality and marriage equality; each religion was ranked from 0 to 4. Higher numbers reflect greater tolerance.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated to describe the demographics, pathways and barriers to

parenthood, and stigma experiences in a variety of social contexts, both globally and by state equality ratings. Reported experiences and avoidance of stigma in each context were dichotomized (experienced, avoided, or not in past year). Overall stigma was calculated as the sum of these dichotomized values across all contexts (range = 0–9 for fathers, and 0–7 for children), although we recognize that stigma in various social contexts may vary in their relative impact on individuals (for example stigma from family members may be experienced differently from stigma in the workplace, etc). Statistical tests of the relations between stigma experiences and state equality ratings, household income, and family racial composition were conducted by using the sum of these dichotomized scores across contexts. These

analyses, as well as those in which the link between the religion’s tolerance scores and stigma

experienced in religious contexts was examined, were conducted as mixed-effects regressions with state-specific random intercepts (to account for clustering within the state) and the distribution defined as log-normal to account for the positively skewed distribution of the dependent variables.

Analyses examining the associations between state equality score and barriers to parenthood by various pathways, and fathers’ experiences of stigma, were conducted similarly, but with an additional parent-specific intercept to account for the fact that some fathers reported on more than 1 child. All inferential statistics were calculated by using the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS software, version 9.4 of the SAS System (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) for Windows.

RESULTS

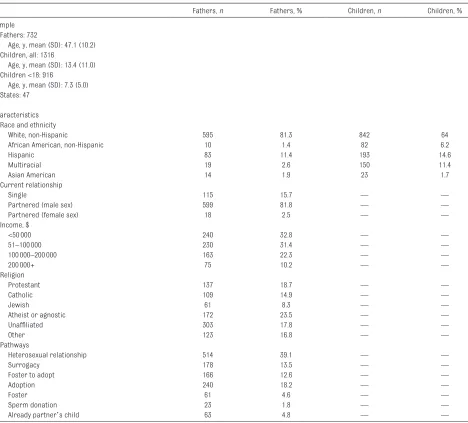

Table 1 describes the sample. In total, 732 fathers reported on 1316 children, with an average age of 13.4 years (916 were <18 years). With an anonymous survey, we cannot know whether respondents were partners or reporting on the same children. The majority (81.3%) of respondents were white and non-Hispanic; 64.2% had earned a bachelor’s degree or higher. Household income ranged from <$25k to >$200k. Over 80% had a male partner, and 2.5% had a female partner.

Pathways to Parenthood

gay men becoming parents in recent years. Over 70% of respondents who became fathers before 1996 had done so in the context of a heterosexual relationship, whereas <6% of respondents who became fathers after 2010 reported this pathway. Fathers had adopted through a private US agency (36.5%), independently (12.8%), via foster care (39.3%), or internationally (8.8%). Because the cost of adoption varies considerably and enlisting the cooperation of a surrogate carrier is often expensive, the pathways used by each respondent were closely

associated with their income. Among fathers with household income <$100000, 78.7% of the children were conceived in a heterosexual relationship, and 18.8% had been foster children. Children of fathers with household incomes >$100000 were more likely to have been born through the assistance of a surrogate carrier (26.2%) or adopted through a private agency (12.5%).

Families in states with fewer legal protections were more likely to have been formed through heterosexual relationships (odds ratio [OR], 1.42; 95% confidence interval [CI],

1.11–1.81). Families living in states with higher equality scores were more likely to have been formed by surrogacy (OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.08–1.84).

Because a growing number of respondents became fathers with the assistance of a surrogate carrier, we explored this pathway further. Most arrangements were made through an agency (70.6%), whereas 12% were arranged through a relative or friend. Usually 1 man’s sperm was used for conception, but 17.5% used a mixed sample from both partners. In 86% of these pregnancies, the egg

TABLE 1 Demographic Information on the Sample

Fathers, n Fathers, % Children, n Children, %

Sample Fathers: 732

Age, y, mean (SD): 47.1 (10.2) Children, all: 1316

Age, y, mean (SD): 13.4 (11.0) Children <18: 916

Age, y, mean (SD): 7.3 (5.0) States: 47

Characteristics Race and ethnicity

White, non-Hispanic 595 81.3 842 64

African American, non-Hispanic 10 1.4 82 6.2

Hispanic 83 11.4 193 14.6

Multiracial 19 2.6 150 11.4

Asian American 14 1.9 23 1.7

Current relationship

Single 115 15.7 — —

Partnered (male sex) 599 81.8 — —

Partnered (female sex) 18 2.5 — —

Income, $

<50000 240 32.8 — —

51–100000 230 31.4 — —

100000–200000 163 22.3 — —

200000+ 75 10.2 — —

Religion

Protestant 137 18.7 — —

Catholic 109 14.9 — —

Jewish 61 8.3 — —

Atheist or agnostic 172 23.5 — —

Unaffiliated 303 17.8 — —

Other 123 16.8 — —

Pathways

Heterosexual relationship 514 39.1 — —

Surrogacy 178 13.5 — —

Foster to adopt 166 12.6 — —

Adoption 240 18.2 — —

Foster 61 4.6 — —

Sperm donation 23 1.8 — —

Already partner’s child 63 4.8 — —

was donated by a separate donor who was permanently anonymous (45%) or could be identified when the child was an adult (23.7%). In 15.3% of cases, the egg donor was a friend or relative of 1 of the partners. In general (>90%), neither the egg donor nor the surrogate carrier was reported to have legal parenting status or to function as a parent figure in the child’s life, but 51% of surrogate carriers continued some involvement with the family after the child’s birth.

Many fathers reported having experienced barriers to becoming or being a parent: 40.6% of those who attempted to adopt a child faced barriers, and 33% had difficulties in arranging for custody of their child(ren) born in a heterosexual relationship. Figure 2 reveals

differences in the number of fathers who described barriers to becoming and/or being a parent in relation to the state’s equality score.

Experiences of Stigma

Almost two-thirds of respondents (63.5%) reported that they had experienced stigma based on being a gay father, and half (51.2%) had avoided situations for fear of stigma, in the past year. Most stigma had occurred in religious environments (reported by 34.8% of fathers). Approximately one-fourth of respondents reported experiencing stigma in the past year from family members, neighbors, gay friends, and/or service providers such as waiters, service providers, and salespeople (see Table 2). Notably,

children’s school and health care environments were unlikely contexts for stigma.

The likelihood of experiencing stigma differed on the basis of the state’s equality rating. In lower-equality states, fathers reported more active (b = −0.059, F1, 682 = 5.10, P = .024) and avoidant (b = −0.054, F1, 680 = 6.30, P = .012) stigma experiences across social contexts, especially in religious settings (OR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78–0.95), among family members (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.90–1.00), and neighbors (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.87–

0.97; Fig 3).

Among fathers who identified with a particular religion, the likelihood of having experienced stigma in a religious context was directly associated with the tolerance ranking of the religious group with which they affiliated; greater tolerance was associated with a lower probability of having experienced active stigma (OR, 0.575; 95% CI, 0.462–0.714). Almost one-third of respondents affiliated with a religious community had avoided such contexts in anticipation of stigma.

Additionally, we looked at whether experiences of stigma differed on the basis of the partnership status of the father (partnered versus nonpartnered), as well as on the basis of the racial composition of the family (at least 1 member is a person of color versus all members are white). We found no significant differences attributable to either characteristic. With 1 exception, there was also no association between reports of stigma among fathers or children and household income. Fathers with household income >$100000 reported slightly fewer instances of avoiding certain social contexts (b = −0.124, F1, 657 = 5.62, P = .018). Fathers reported few stigma experiences related to having gay parents directed at children from family members, neighbors, or in religious, school, or health care

FIGURE 1

contexts. However, 32.8% of fathers reported that their child(ren) had experienced active stigma in the past year from their own friends,

and almost 19% reported that their child(ren) had avoided friendship activities for fear of experiencing stigma.

DISCUSSION

This national sample of gay fathers reflects historical changes in pathways through which gay men have become parents, as previously reported.21 Adoption and surrogacy,

2 routes dependent on systems supporting the formation of families, have been increasingly common in recent years and in states with more legal protections, whereas heterosexual relationships were more common in earlier years and in states with fewer protections. Respondents reported experiencing difficulties in the process of becoming fathers by all methods, more often in states with fewer legal protections. Despite encouraging legal and social changes, gay men and their children still face stigma and discrimination. It is noteworthy that >60% of gay fathers experienced stigma in at least 1 context within the past year. Because perceived stigma has been shown to interfere with both mental and physical health, 22–24 we

attempted to understand the extent and contexts of these experiences. The reported stigma experiences occurred most often in the context of religious institutions, but some fathers also reported experiencing exclusion and discrimination at the

FIGURE 2

Barriers to parenthood by state equality score. Custody refers to obtaining legal custody of the child(ren) after divorce.

TABLE 2 Number and Percent of Fathers and Children Who Experienced and Avoided Stigma by Social Context

Father Stigma Child Stigma

Active Avoid Active Avoid

n % n % n % n %

Family 169 23.9 147 20.7 35 10.6 32 9.5

Neighbors 195 27.7 146 20.7 46 14.7 32 10.2

Religious 151 34.8 141 31.9 37 17.0 28 13.0

Health care 78 11.2 49 7.02 12 3.7 9 2.7

Child’s school 91 18.3 5 10.1 50 16.4 25 8.2

Dad’s gay friends 167 23.7 107 15.2 NA NA NA NA

Dad’s straight friends 141 19.7 101 14.1 NA NA NA NA

Workplace 111 16.3 94 13.7 NA NA NA NA

Restaurant, salespeople 180 25.5 89 12.7 NA NA NA NA

Child’s friends NA NA NA NA 96 32.8 54 18.6

Child’s extracurriculars NA NA NA NA 42 14.3 27 8.9

Only 1 context 159 21.8 159 21.9 59 16.8 50 14.2

2–3 contexts 165 22.6 125 17.2 54 15.3 30 8.6

4 or more contexts 139 19.1 88 12.1 27 7.7 18 5.1

hands of their families, neighbors, and friends. Although these experiences were not commonly reported, the fact that they happened in settings that are traditionally expected to be sources of support and nurturing is particularly troubling. It is important for

pediatricians caring for these families to help families understand and cope successfully with potentially stigmatizing experiences.

The legal protections afforded in each state to its LGBT citizens are disparate and have a meaningful link to the experience of gay fathers and their children. Both active and avoidant stigma were reported more frequently by fathers who lived in states with fewer legal protections. The amount of community support provided to members of sexual minorities has been shown to be related to the well-being of lesbian and gay adolescents, 25, 26 adults, 24, 27

and children with lesbian or gay parents, 28 including rates

of suicidality and psychiatric

disorders.29, 30 Particularly relevant

is the recent work demonstrating the associations between structural stigma (eg, state equality scores, religions’ tolerance ratings) and indicators of individual mental health. Given their important role as leaders in the community’s support for all families, pediatricians caring for children and their gay fathers should recognize the likelihood that stigma may be a part of the family’s experience and help both families and communities to counteract it. Pediatricians also have the

opportunity to be leaders in opposing discrimination in religious and other community institutions.

This study has limitations that must be considered. The recruitment of the sample through informal distribution networks, and its limited ethnic and/or racial diversity limit its generalizability; however, the sample size of >700 fathers from 47 states is a strength. Fathers’ responses were anonymous, constraining our ability to determine whether fathers

reported on multiple children or fathers were partners. We believe that anonymity increased the number of respondents, especially in low-equality states. We did not use a standardized stigma scale; unfortunately, appropriate scales are still in their infancy. Despite a renewed interest in studying prejudice and discrimination and assessing their impact on health outcomes, individuals tend to underreport these experiences and psychometrically valid measures are still not available.31 In addition,

it is difficult to correctly categorize variations in social environments, especially in the context of rapid political change. We relied on the Movement Advancement Project’s assessment of the legal protections in place in 2012 in each state, and on Hatzenbuehler et al’s20 calculations

to estimate religious climate.

CONCLUSIONS

We provide information about gay fathers and their children that will be helpful for clinical care and advocacy. Discussions of decisions about and pathways to parenthood can facilitate understanding of families and children. Ongoing health supervision should include discussions about stigma and help families learn strategies to counteract its corrosive effects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate many people’s contributions to this study. We thank all the men who took the time in the midst of their busy lives as parents to respond to our survey and to pass it along to their friends. Many people contributed financially to allow us to create and distribute the survey and to do the analyses: James D. Marks, Mark Scott, Mark Hostetter, Alexander Habib, William Donnell, Robert Mancuso, and Richard Meelia. In addition, we appreciate supplementary funding

FIGURE 3

provided by the Boston Gay Rights Fund, the Gill Foundation, and the Arcus Foundation. We profited from the advice of Josh Rosenberger and Kelly Woyewodzic in the design of the survey instrument. Our advisory group provided wise feedback

about the construction of the survey instrument and about its distribution, including William Lewis Walker, Ricardo Antonio Tan, Liming Zhou, Kevin Johnson, Christopher Harris, Ru Ortiz, Miguel Stevens-Ortiz, and Edward Coleman.

REFERENCES

1. Cornell University. What does the scholarly research say about the well-being of children with gay or lesbian parents? Available at: http:// whatweknow. law. columbia. edu/ topics/ lgbt- equality/ what- does- the- scholarly- research- say- about- the- wellbeing- of- children- with- gay- or- lesbian- parents/ . Accessed December 8, 2018

2. Tasker F. Lesbian mothers, gay fathers, and their children: a review. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26(3):224–240 3. Perrin EC, Siegel BS; Committee on

Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Promoting the well-being of children whose parents are gay or lesbian. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4). Available at: www. pediatrics. org/ cgi/ content/ full/ 131/ 4/ e1374

4. Patterson CJ, Riskind RG. To be a parent: issues in family formation among gay and lesbian adults. J GLBT Fam Stud. 2010;6(3):326–340 5. D’Augelli AR, Rendina HJ, Sinclair

KO, Grossman AH. Lesbian and gay youths aspirations for marriage and raising children. J LGBT Issues Couns. 2007;1(4):77–98

6. Golombok S, Tasker F. Gay fathers. In: Lamb ME, ed. The Role of Father in Child Development. New York, NY: Wiley; 2010:319–333

7. Tasker F. Lesbian and gay parenting post-heterosexual divorce and separation. In: Goldberg AE, Allen KR, eds. LGBT-Parent Families: Innovations in Research and Implications for Practice. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:3–20

8. Bos H. Lesbian-mother families formed through donor insemination. In: Goldberg AE, Allen KR, eds. LGBT-Parent Families: Innovations in Research and Implications for Practice. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2013:21–37 9. Goldberg AE. Gay Dads: Transition to

Adoptive Fatherhood. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2012 10. Farr RH, Patterson CJ. Lesbian and gay

adoptive parents and their children. In: Goldberg AE, Allen KR, eds. LGBT-Parent Families: Innovations in Research and Implications for Practice. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2013:39–55 11. Gianino M. Adaptation and

transformation: the transition to adoptive parenthood for gay male couples. J GLBT Fam Stud. 2008;4(2):205–243

12. Berkowitz D. Gay men and surrogacy. In: Goldberg AE, Allen KR, eds. LGBT-Parent Families: Innovations in Research and Implications for Practice. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2013:71–85

13. Gates GJ. LGBT parenting in the United States. Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute; 2013. Available at: http:// williamsinstitute . law. ucla. edu/ wp- content/ uploads/ LGBT- parenting. pdf. Accessed December 8, 2018

14. Perrin EC, Pinderhughes EE, Mattern K, Hurley SM, Newman RA. Experiences of children with gay fathers. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;55(14):1305–1317 15. Vinjamuri M. Reminders of

heteronormativity: gay adoptive fathers navigating uninvited

social interactions. Fam Relat. 2015;64(2):263–277

16. Riggs DW, Due C. Gay fathers’

reproductive journeys and parenting experiences: a review of research. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2014;40(4):289–293

17. Furlong M. Planned gay father families in kinship arrangements. Aust N Z J Fam Ther. 2010;31(4):372–373 18. Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing

stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–385

19. Hatzenbuehler ML. Structural stigma: research evidence and implications for psychological science. Am Psychol. 2016;71(8):742–751

20. Hatzenbuehler ML, Pachankis JE, Wolff J. Religious climate and health risk behaviors in sexual minority youths: a population-based study. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(4):657–663

21. Tornello SL, Patterson CJ. Timing of parenthood and experiences of gay fathers: a life course perspective. J GLBT Fam Stud. 2015;11(1):35–56 22. Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: a prospective study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(3):452–459

23. Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J. How does stigma “get under the skin”?: the mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychol Sci. 2009;20(10):1282–1289

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. FUNDING: Funded by the Gil Foundation, Arcus Foundation, and private donations.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

ABBREVIATIONS

CI: confidence interval

LGBT: lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender

24. Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Starks TJ. The influence of structural stigma and rejection sensitivity on young sexual minority men’s daily tobacco and alcohol use. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:67–75

25. Hatzenbuehler ML, Jun HJ, Corliss HL, Austin SB. Structural stigma and cigarette smoking in a prospective cohort study of sexual minority and heterosexual youth. Ann Behav Med. 2014;47(1):48–56

26. Hatzenbuehler ML, Pachankis JE. Stigma and minority stress as social determinants of health among lesbian,

gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: research evidence and clinical implications. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63(6):985–997

27. Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. State-level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(12):2275–2281

28. Lick D, Tornello S, Riskind R, Schmidt K, Patterson C. Social climate for sexual minorities predicts well-being among heterosexual offspring of lesbian and gay parents. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2012;9(2):99–112

29. Hatzenbuehler ML. The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):896–903

30. Raifman J, Moscoe E, Austin SB, McConnell M. Difference-in-differences analysis of the association between state same-sex marriage policies and adolescent suicide attempts. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(4):350–356

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2018-0683 originally published online January 14, 2019;

2019;143;

Pediatrics

Pinderhughes

Ellen C. Perrin, Sean M. Hurley, Kathryn Mattern, Lila Flavin and Ellen E.

Barriers and Stigma Experienced by Gay Fathers and Their Children

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/143/2/e20180683

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/143/2/e20180683#BIBL

This article cites 23 articles, 3 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/lgbtq

LGBTQ+

al_issues_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/development:behavior

Developmental/Behavioral Pediatrics

_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/community_pediatrics

Community Pediatrics following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2018-0683 originally published online January 14, 2019;

2019;143;

Pediatrics

Pinderhughes

Ellen C. Perrin, Sean M. Hurley, Kathryn Mattern, Lila Flavin and Ellen E.

Barriers and Stigma Experienced by Gay Fathers and Their Children

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/143/2/e20180683

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.