Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Computers

&

Security

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cose

The

rise

of

crypto-ransomware

in

a

changing

cybercrime

landscape:

Taxonomising

countermeasures

Lena

Y.

Connolly

∗,

David

S.

Wall

Cybercrime Group, Centre for Criminal Justice Studies, School of Law, University of Leeds, UK

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Article history:

Received20February2019 Revised9July2019 Accepted10July2019 Availableonline10July2019

Keywords: Crypto-ransomware Malware Socialengineering Securitycountermeasures Managementsupport Organisationalsettings Cybercrime

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Year in and year out the increasing adaptivity of offenders has maintained ransomware’s position as a major cybersecurity threat. The cybersecurity industry has responded with a similar degree of adaptive- ness, but has focussed more upon technical (science) than ‘non-technical’ (social science) factors. This article explores empirically how organisations and investigators have reacted to the shift in the ran- somware landscape from scareware and locker attacks to the almost exclusive use of crypto-ransomware. We outline how, for various reasons, victims and investigators struggle to respond effectively to this form of threat. By drawing upon in-depth interviews with victims and law enforcement officers involved in twenty-six crypto-ransomware attacks between 2014 and 2018 and using an inductive content analysis method, we develop a data-driven taxonomy of crypto-ransomware countermeasures. The findings of the research indicate that responses to crypto-ransomware are made more complex by the nuanced rela- tionship between the technical (malware which encrypts) and the human (social engineering which still instigates most infections) aspects of an attack. As a consequence, there is no simple technological ‘sil- ver bullet’ that will wipe out the crypto-ransomware threat. Rather, a multi-layered approach is needed which consists of socio-technical measures, zealous front-line managers and active support from senior management.

Crown Copyright © 2019 Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license. ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

1. Introduction

Inaworldofcloud-drivencomputing,manybusinessesand or-ganisations now rely wholly upon their IT and data systems to function effectively,to thepoint that“ITservices arebecoming a critical infrastructure, much like roads, electricity, tap water and financial services” (Franke,2017, p.130). Realising the importance of these IT assets to organisations, since early the 2000s cyber-criminals have increasingly explored different cyber-tactics to at-tackbusinesses(Wall,2015).Inrecentyears,offendershavesought toextortmoneyviacrypto-ransomwareattacks.Thisformof mal-ware scrambles valuable data with virtually-unbreakable encryp-tionanddoesnotrelease(decrypt)ituntilaransomispaid.Thisis asignificantshiftfromearlyvariantsofransomwaresuchas scare-ware andlockers andithasincreased theimpact ofransomware andtheoverallseriousnessofthethreat.

Thisarticleempiricallyexploreshoworganisationsand investi-gators have responded to the shift inthe ransomware landscape from scareware and locker attacks to the almost exclusive use

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mail address: alena.yuryna-connolly@fulbrightmail.org(L.Y.Connolly).

ofcrypto-ransomware. In it,we draw upon empiricalresearch to outline how, forvarious reasons, victims andinvestigators strug-gle to respondto thisform ofthreat effectively. In Section 2we describe changes in the ransomware landscape and explore the strengthsandweaknesses oftheliterature toidentifythekey re-searchobjectives.Section3outlinesthemethodologytoundertake theresearchandinSection4,wepresentanddiscussourfindings.

Section5concludes. 2. Background

2.1. The rise of crypto-ransomware

Asindicatedearlier,theransomwarelandscapeischanging dra-matically. In2018, Sophos found that half (54%) ofthe organisa-tionsthey surveyedhadbeenavictimofransomware inthe pre-viousyear withanaverage two attackseach.The healthcare sec-tor was hit most, followed by energy, professional services, and theretailsector.Indiahadthehighestlevelofinfection,followed byMexico,U.S.,andCanada.Threequarters(77%)oforganisations wererunningout-of-dateendpointsecurityatthetimeofthe at-tackandhalf(54%)didnothavespecificanti-ransomware protec-tioninplace(Sophos,2018).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2019.101568

Not surprisingly, when organisations are hit by crypto-ransomware,the costs ofrecovery are considerable.For example, Sophosfound intheir 2018survey thatthe mediancost ofan at-tack was $133,000, with most organisations experiencing losses of between $13,000 and $70,000 – a lot of money for a small enterprise which often omits hidden costs such as loss of repu-tation. These costs are overshadowed by the larger ransomware worm attacks, such as NotPetya, where international shipping firm Maerskis estimatedto havelost up to $300 million dollars (Mathews,2017).Theoverallcostofransomwaredamagesfor2017 wasestimatedtobe$5billionanditispredictedtoreach$11.5 bil-lionin2019(Morgan,2018).

In addition to significant financial losses, the risk of ran-somware victimisation has increased by 97% since 2017 (Dobran, 2019) andthe trend is continuing. Morgan (2018) esti-matedthatbytheendof2019 ransomwarewillattackabusiness every14sdecreasingto11sin2021.Thisiscomparedto40sin 2016 as reported by Kaspersky (Ivanov et al., 2016). The picture becomeseven more gloomy when new forms of attack enablers are considered such as Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) which opensthe‘gates’tooffenderswithouttechnicalexperience.

As the ransomware threat grows, then so does the list of offenders and the increased sophistication of their victimisation techniques. Ransomware actors (especially the enabling brokers who provide RaaS) increasingly employ advanced delivery tech-niques,includingpowerfulbotnets capable ofsendingmillions of maliciousmessagesper dayandalso Internetscanners that iden-tifyvulnerable Internet Protocol (IP) addresses. Furthermore,the useofanonymisedplatformsontheDarkWeb,spoofed email ad-dressesandcryptocurrenciesforpaymentsmakes iteasierfor of-fenderstoconcealtheirdigitalfootprints(Tayloretal.,2019).

All ofthesedevelopments intheransomware landscapemake it much harder forlaw enforcement agencies to investigate ran-somwarecrimesandisnothelpedby theoffender’suseofstrong encryptionwhichmakes ithardforvictimstoresisttheattackers demands.Ifvictims donothavebackupsinasecurelocationand thelostinformationismission-orsafety-critical,the incentiveto paytheransom ishigh, whichstrengthens theransomware busi-ness model.Even supposed decryption services havebeen found topaytheransomtoreleasethedataratherthanspendtime de-cryptingit(DudleyandKao,2019).

2.2. Related work

The subjectof ransomware hasreceived much attention from academics,practitionersandgovernmentbodies(Broadhead,2018). The FBI (2018), the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) (2018) and Europol (2016) issued documents providing guide-lines on how to protect organisations from ransomware. The

FBI (2018) warned that prevention is the most effective defence against ransomware, and it is critical to take precautions for protection. Security vendors are responding by offering sophis-ticated technical solutions against ransomware. Since 2016, due to its prevalence, Cyber Threats Reports by the European Union Agency for Network and Information Security (ENISA) included ransomwareas aseparate threat frommalware, offeringrelevant informationandstatistics(ENISA,2018).

Our search of the scholarly literature revealed that research onransomware has particularly mushroomedsince 2016. We re-viewed over 100 academic papers in ScienceDirect, IEEEXplore, ACM Digital, and Google Scholar databases. Technical analysis of ransomware (Subedi et al., 2018; Zimba et al., 2017) has im-proved our understanding of how this threat operates, subse-quentlyleadingtopromisingremedies.Ransomware countermea-sures research emphasised the importance of security education (Simmonds,2017),policies(RichardsonandNorth,2017),and tech-nical controls such as detection (Jung and Won, 2018),

securely-configured software andhardware(Saxenaand Soni,2018), anti-virus (AV) software (Pathak and Nanded, 2016), email hygiene (Jakobsson, 2017), and Intrusion PreventionSystem (Adamov and Carlsson,2017).Organisationsareadvised toupgradeold systems (Mansfield-Devine,2018),executeregularpatching(Gagneja,2017), apply the “least privileges” approach (Parkinson, 2017), segregate the network perimeter (Fimin, 2017), and implement effective backuppractices(GonzalezandHayajneh,2017).Additionally, sev-eralrecoverysolutionshavebeenproposedtorestore (Baeketal., 2018)ordecrypt(Kolodenkeretal.,2017)filesthatwerescrambled duringtheattack.

Although the abundance of research in ransomware demon-strates that academic and practitioner communities are acutely aware of the problem and are keen to find suitable solutions, mostof theliterature on ransomware focusesentirelyon techni-calsolutions,withtheexceptionofjustafew(forexample,Fimin, 2017; Gagneja, 2017; Richardson andNorth, 2017). Limitations of solelyfocusingontechnicalsolutionsinthecontextofcyber inci-dents has been already acknowledged in the academic literature (Connolly et al., 2017a). As Franke (2017, p.131) put it, “security breachescannotbe preventedby technicalmeansalone”.Besides, contemporaryresearch acknowledges the importance ofan inter-disciplinary approach to combatting cyber threats (Choo, 2014). Moreover, despite recent technical advancements (for example, AV softwarethat containsdedicatedransomware protection algo-rithms in place, advanced email filters etc.), ransomware attacks continuetohurtorganisationsaroundtheglobe.

Ransomware is not simply a technical problem, but an inter-disciplinary one (Sittig and Singh, 2016). Offenders increasingly usesocialengineeringtechniquestopenetrateorganisational net-worksasthefirstpointofentry.Theelementofextortionincludes manypsychologicaltricksinordertoforcevictims topay, includ-ing count-down clocks,explicit warnings ofconsequences of los-ingdata,anoffertoprovidesecurityadviceinordertoavoid sub-sequent attacks,or a strict deadline to pay withvery little time to think (in some cases only 24 h is given to victims to make thedecision).Professionaloffendersemploybusinessmodelsto as-sesstheoptimalransomamount.Ransomwareincidentsrepresent a complexecosystem andadversary actors exploit acombination ofweaknessescomprisingofthe‘humanfactor’element,technical shortcomings, the lack of expertisein the security domain, poor leadershipandinsufficientfundinginorganisations.Therefore,the objective of thisstudy is to understand the dynamics of crypto-ransomwareattacks andinformsolutions that willhelp organisa-tions respondto these incidents. We approach the issue of ran-somware holistically and take a more inclusive stance in under-standinganddefeatingthisthreat.

To the best of our knowledge, no similar research with such a specific focus on crypto-ransomware has yet been conducted. Crypto-isthefocusofthispaperasitiscurrentlythemost preva-lent type of ransomware when compared to lockers and scare-ware,andit inflictsmostdamage duetoits frequent irreversibil-ity. Moreover, empirical investigations of ransomware attacks are rarely reported.Our own literature searches discovered only one paper by Shinde et al. (2016), in which the authors based their findingsonasmall-sample surveyandtwo interviews.By collect-ingdata directlyfromvictims, practitionersandpolice,we devel-opedacomprehensivesetofpracticalrecommendationswhichare illustratedlater.

3. Researchmethod

We adopteda qualitative research approach usingan inductive content analysis method asa suitable methodology to reach this study’sgoal.Qualitativeinquiries aimto gaina deep understand-ingofaphenomenonunderstudy(MaykutandMorehouse,1994). We conducted a series of qualitative semi-structured interviews

and held a focus group through which we probed and explored in order to generate rich data and obtain a deep understanding of crypto-ransomware from an interdisciplinary perspective. Our sample comprised of individuals who had first-hand experience with crypto-ransomware attacks as victims or investigators, the latterincluded PoliceOfficersfromUK’s various cybercrimeunits (CCU). We also drew upon secondary data in the form of inter-viewfollow-upemailsandconfidentialIncidentReportssharedby victims. These secondary data sources were found to be useful throughout thedata analysisfor post-interview clarifications and verifying results.Inourdata collectionquest,we were interested inhoworganisationsbecameinfectedandhowtheysubsequently recovered. We focused on their self-reflections prior to and dur-ing the attacksand alsoanypractices that helped themmitigate attacksandrecoverquickly.Finally,wedrew outanylessonsthat victims learnedasaresultoftheattacksandlooked atthe post-attackorganisationalchangesthattheyimplemented.Weusedthe data to develop an all-inclusive taxonomy of crypto-ransomware countermeasures consisting ofa) socio-technical measures b) ac-tionsforfront-linemanagersandc)seniormanagement.This tax-onomy will be useful as the basis for a guide for practitioners whichwillenablean effectiveresponsetocrypto-ransomware at-tacks.

3.1. Sampling strategy

Twenty-six purposefully selected ransomware incidents were exploredindepth.Theattackstookplacebetween2014and2018. Theycomprisedofdiversecrypto-ransomwareexamples,including recently-emergedvariantssuchasCerber,Samas,BitPaymer, Wan-naCry, Dharma, andHiddenTear andoldersamplessuch as Cryp-toWall,CryptoLocker,TeslaCrypt, andKeyHolder.Seekingtofinda balancebetweentargetinghumansandmachinesasan initial vic-timisation point, we included a variety ofattack vectorssuch as malicious emails, brute-force, anddrive-by-downloads. Our sam-ple was comprised of organisations of various sizes, industries, andfromboth public andprivatesectors. The impact ofthe ran-somware attacks ranged from mild disruptions with a relatively quick recovery to severe outcomesthat affected theoperation of thebusinessesformonths.

Details of the attacks and the victim organisations who par-ticipatedin thisresearch are outlined inTable 1.It indicates the victim’s industry, organisation size and sector, and attack vector andtarget(humanormachine).Torespecttherespondents’ confi-dentiality,aliasesareusedandransomamountsconcealedasthey could otherwisebeusedtoidentifysome oftheinformants.Also, the names of theransomware variants and the time ofthe inci-dentswereintentionallynotlinkedtoorganisations’aliasesto fur-therpreservetherespondents’anonymity.Theseextraprecautions helpedusgaintrustoftheintervieweesandcollectsomevery sen-sitivedata.

3.2. Data collection

The data was collected between January and December 2018 andsampleinterviewquestionsare illustratedinAppendix1.The majorityofinterviews wereconductedface-to-face,buta few in-terviewswithoverseasrespondentswereconductedbySkypeand one wasdonevia emailcorrespondence. Whilstselecting respon-dents,wesoughtprofessionalswhohaddirectexperienceof deal-ing withtheransomware incidents.A totalof22respondents di-rectly participated in the research (5 in the focus group and 17 ininterviews).TheintervieweesincludedtenIT/SecurityManagers andExecutiveManagerswithanaverageof17yearsofprofessional experience, as well as six Police Officers with an average of 19

yearsofexperienceinthefield.Additionally,aSecurityResearcher froma cyber security company with15 years of experience was interviewed.Finally,afocusgroupwasconductedwithfour Detec-tiveConstables workinginthefield andaCivilianCybercrime In-vestigatorwhotogetherhadanaverageofsevenyearsinthefield. The average duration of interviews was about one hour and ten minutes,resultingin 386pages oftranscribedtext inaddition to 119pagesofdocumentation.

In any qualitative research, resource constraints often dictate whendatacollectionends,however,apointofsufficient “theoreti-calsaturation” isnormallyreachedafteraboutadozenorso obser-vations(MilesandHuberman,1994,pp.30–31;Eisenhardt,1989). In this study, we felt that we reached the point of diminish-ing returns after about twenty cases and in total we examined twenty-six crypto-ransomware incidents even though the incre-mentallearninghadalreadyreachedaplateau.

3.3. Data analysis procedure

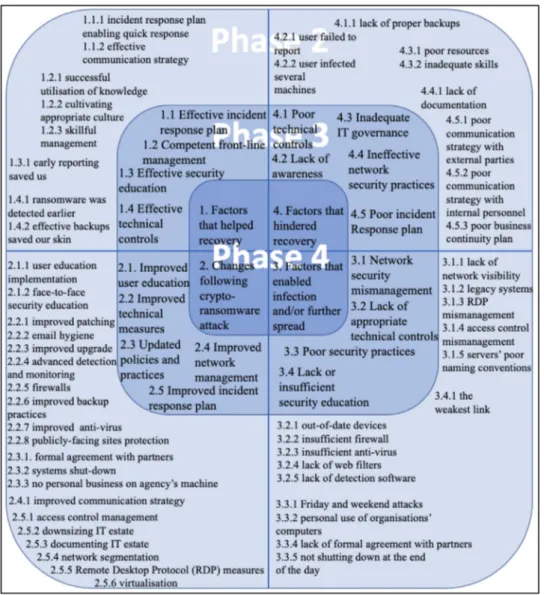

Thedataanalysisconsistedoffivephases(Fig.1).Phase1(open coding )beganwithreadingthroughtranscribedtextto“obtainthe sense of the whole inorder to learn what is going on, before it canbebrokendownintosmallermeaningunits” (Bengtsson,2016, p.11). Eachidentified unit was first condensed and then labelled with the code (Appendix 2). The process of open coding refers toanon-hierarchicalparticipant-drivendeconstructionofdataand resulted in112 distinctive codes (Appendix 3), includingpositive (1.1.1.1–2.5.5.2) and negative (3.1.1.1–4.5.3.1) codes. Positive codes representexperiencesthathelpedorganisationsrespondtoattacks, whilenegativecodesrefertofactorsthatinitiatedtheinfection, fa-cilitateditsfurtherspread,andhinderedtherecovery.Changes im-plementedafterattackshavebeenalsoreflectedinpositivecodes. InPhase2,the process of categorisation tookplace(seeFig.2for greaterdetail). Categories were identifiedandunits oftextsfrom Phase 1 were sorted into categories. Data units that fitted with theidentifiedcategoriesvalidatedthatcategory.Furthermore,data unitsthat failedtofit withexistingcategoriesgenerated leadsto theformationofadditionalcategories.Overthecourseofthis an-alyticalprocess the categoriesunderwent various changes: while someofthem weresubstantiatedquickly,others wereeliminated as irrelevant to the focus of inquiry; some were merged due to overlaporneededtobe re-defined, andnewcategories emerged. Due to the large volume of qualitative data, further sorting was required,andcategorieswere grouped into themes inPhase3(see

Fig.2).Bengtsson(2016,p.12)stressedthat“identifiedthemesand categories should be internally homogenous and externally het-erogeneous, which means that no data should fall between two groupsnor fit intomore than one group”;we certainly metthis condition.ThethemesfromPhase3werefurthersortedintofour overarching themes inPhase4(seeFig.2).

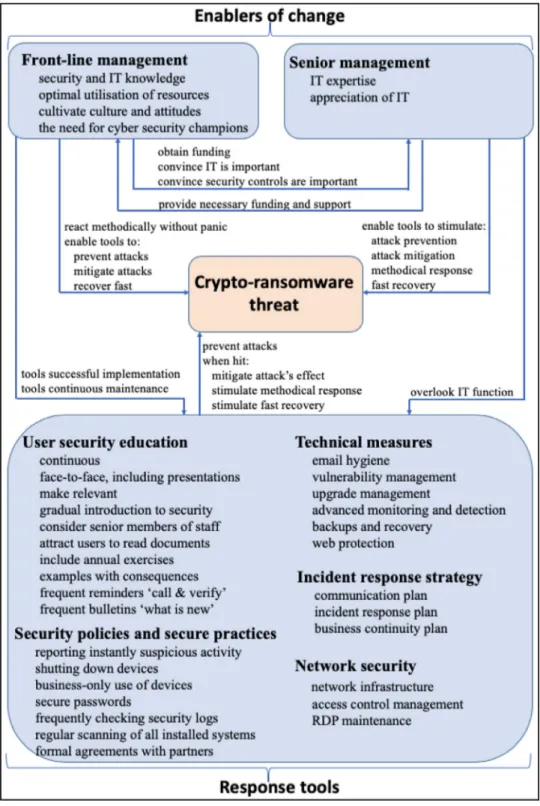

Inthefinalphase(Phase5),negativecodeswereconvertedinto positive,leadingto theformationof taxonomy that consistsof re- sponse tools (controlsandmeasures necessarytoimplementin or-ganisationsin ordertorespondto crypto-ransomwareeffectively) and enablers of change (a group of employees who must ensure theorganisationispreparedforcyber-attacks) (seeFig.3).To en-sure the validity of data analysis, and maintain the quality and trustworthiness of theprocedure, each phase waspeformed sev-eraltimes.Appendix 2transparently representsthe process from rawdatatoresultsrequiredto ensurethequalityofanalysis.The useofsecondary data wasa furthercheck on the validityof the dataanalysis;secondarydatawasalsousedthrougoutallphasesof dataanalysis(togetherwithprimarydata)asanimportantsource ofpost-interviewclarifications.

Table1

Aprofileofrespondents,organisationtypeandattackdetails.

Organisationalias Industry;size;sector Attackvector(s) Attackertarget LawEnfJ Lawenforcement;small;public Email Human GovSecJN Government;large;public Email Human GovSecJ Government;large;public Multipleattacks: Multipleattacks:

1.Drive-by-download 1.Machine 2.Email 2.Human 3.Drive-by-download 3.Machine 4.Drive-by-download 4.Machine EducInstF Education;large;public Drive-by-download Machine EducInstFB Education;large;public Brute-force Machine LawEnfM Lawenforcement;small Multipleattacks: Multipleattacks:

1.Email 1.Human 2.Email 2.Human GovSecA Government;large;public Bruteforce Machine LawEnfJU Lawenforcement;medium;public Maliciousemail Human HealthSerJU Healthservice;large;public Multipleattacks: Multipleattacks:

1.Brute-force 1.Machine 2.Maliciousemail 2.Human LawEnfF Lawenforcement;medium;public Maliciousemail Human ITOrgA IT;small;private Bruteforce Machine ConstrSupA Construction;small;private Bruteforce Machine EducOrgA Education;small;public Bruteforce Machine SecOrgM IT;small;private Email Human ITOrgJL IT;small;private Bruteforce Machine CloudProvJL IT;small;private Bruteforce Machine InfOrgJL Infrastructure;medium;private Bruteforce Machine ConstrSupJ Construction;small;private Bruteforce Machine RelOrgJ Religion;medium;private Email Human SportClubJ Sport;large;private Bruteforce Machine UtilOrgD Utilities;large;private Bruteforce Machine

Fig.1. Thephasesofdataanalysis.

3.4. Reliability and validity of findings

Severalmeasuresweretakentoverifythestudyresultsand en-sure the reliablity of the findings. First, the employment of the purposefulsamplingtechniquepreventedsamplingdistortion. Sec-ond,thesamplesizewasdeterminedbytheprincipleof theoreti-calsaturation.Third,secondarydataservedasanimportant valida-toroffindings.Fourth,wealsoaskedrespondentstoprovide feed-backoninterviewtranscriptsandstudyfindingsandsubsequently madeappropriate corrections. Fifth,the resultswere shared with anexperiencedresearcherfromTrendMicro,whoprovided impor-tantexpertcomments.Sixth,allfindingsaresupportedby intervie-wees’quotes,providingadditionalverification.Finally,thehigh de-greeofunanimityamongstudyinformantsaboutthenecessary or-ganisationalmeasurestorespondtothecrypto-ransomwarethreat suggeststhat the results are reliable and will not change signif-icantlyifadditionalorganisationswere tobeinterviewed.We be-lievetheseprecautionshaveeliminatedmostinaccuraciesand mis-understandingsfromthedatacollection.Althoughwedonotclaim thatthelistofproposed measuresisexhaustive,theutilisationof theaforementionedmeasuresensuresreasonablyreliableresults.

As for the validity offindings, the situation isgenerally more complex if the chosen method is interview because the inter-view process inevitably allows participants to answer questions in waysthat distort the facts. However, in this study, the

situa-tionappears tobe unique,that isparticipants hadvarious incen-tives to provide factual answers. Although we do not claim that the study participants were entirely honest or forthcoming, sev-eralfactorsallowustoconcludethatintervieweesprovided trust-worthyreplies.First,themajorityofvictimssufferedgreatlyfrom crypto-ransomware attacks, including personal emotional distress as well asphysical damage to the IT infrastructure. The key in-centive forparticipation in this studywas to share their experi-ences with the aimto prevent future attacks on other organisa-tions. Intervieweesappeared to be genuinely concerned withthe threat that crypto-ransomware presents,including its recent pro-liferationandtheconsequencesitmayentail,andseveral respon-dents strongly disapproved the fact that many organisations are hiding cyber-attacks. Second, several interviewees were appalled bythefactthatcriminalsheldthemhostagesandwantedto‘share their story’ and warn other organisations. Third, almost all vic-tims actively participated invalidation exercises andexpressed a keeninterestinreceivingfinalfindings.AsforPoliceOfficersfrom the CCUs, the very nature of their job is to reduce cybercrime. Hence, they have a genuine interest in providing objective data. Ourobservationwasthat lawenforcementrepresentatives readily shared data on ransomware attacks, carefully concealing victims’ identities. Other tactics that may haveensured honestyin infor-mants included clearly-communicated anonymity procedures, an optionto changeor deletepartsof text inthe transcriptsandin

Fig.2. Dataanalysisresults(Expandingphases2–4).

thispaper, andevento withdrawfromthestudy atanypoint of time.

4. Studyfindingsanddiscussion

The taxonomy’s components (response tools and enablers of change such asfront-line managersand senior management; see

Fig. 3) were derived from an analysis of the data from semi-structured interviewswhich sought toobtain respondents’ reflec-tions upon their personal experience of responding to crypto-ransomwareattacks.ThesenexttwoSections(4.1and4.2)outline theviewsoftherespondentswhichledtothetaxonomy.

4.1. Response tools

Theintervieweesfeltthatanall-roundcomprehensiveapproach towards security is absolutely vital in order to protect organisa-tions against ransomware attacks.Morespecifically, they strongly emphasised the importance of user security education, technical measures, network security, security policies and secure practices ,and the incident response strategy as essential response tools to pro-tect organisations against crypto-ransomware (see Fig. 3). As the IT/SecurityManager,GovSecJNputit:

“Theimportanceofacomprehensiveapproachtosecurity can-not be underestimated. That is, not only relying on controls whichpreventthesesortsofattacksformhappeninginthefirst place,butalsohowyouthenreactwhenyouarehit.Notifyou arehit,whenyou arehit.Becauseeverybodywillbehitifyou connecttotheInternet”.

Preparation istherefore essential, butas EducInstFBand Gov-SecJN warned, even with all the appropriate measures imple-mented, an organisationcan still easily become a victim. Never-theless,awell-preparedorganisationwillbeabletorespond effec-tively:

“Whentheransomwarehit,wewerenotpanicking.Wepractice goodbasicsecurityprinciples,sowewereconfident.Weknew thatwehadsolidbackups.We hadtheminmultiplelocations andthosefilesthatwereaffectedweregoingtobe easyto re-cover.” (IT/SecurityManager,LawEnfJ)

GovSecA,incontrast,hadnopropersecuritymeasuresinplace. Parts oftheir systemwere out-of-date,the networkmanagement was poor, there was no security education and they lacked an incident response strategy. The organisationalso suffered froma chroniclackoffundingandpoorleadership.Subsequently,the

ran-Fig.3. Ataxonomyofcrypto-ransomwarecountermeasures.

somwareattack hada severeimpact, making itunable to deliver criticalservices to customers for manymonths as well as a sig-nificantloss ofsensitive data. At thetime of the interview, Gov-SecAhadalreadybeenina post-attackrecoveryprocess foreight months and the interviewee stressed that the recovery was still notcompleted.

Although ourliterature search revealeda biastowards techni-cal advancements,our findingssuggest that a comprehensive ap-proachtosecurityisessentialtocountercrypto-ransomware. This is in line with research that focuses on cyber security in

gen-eral. For example, Kraemer et al. (2009) argued that a compre-hensiveapproach isnecessary tostrengthencybersecurity in or-ganisations.Bulgurcuetal.(2010)stressedthatalthoughtechnical controls help improve security in organisations, relying on them exclusively is seldom enough to combat cyber threats. While or-ganisations invest more in technology-based solutions, the over-all numberof securityincidentsis on therise (Thales, 2018). In-deed, technicalcontrols are importantbut neverthelesscomprise onlyaportionoftheall-inclusiveapproachdevelopedinthisstudy (Fig.3).Thebottomlineisthatthereisnosingleuniversalsolution

tocrypto-ransomwareattacks.Theproverbialsilverbulletdoesnot exist;rather,asuiteofmeasuresisrequiredwhichtakesonboard thetaxonomy(Fig.3).

4.1.1. User security education

The interviewees stressed that successful defence starts with usersecurityeducation,self-definedas continuous, face-to-face ,and relevant because“anorganisationisasvulnerableasitsleastsavvy user” (Executive Manager, EducInstFB). Education that gradually introduces users to security concepts, takes in consideration senior members of staff, attracts users to read relevant documents ,and in- cludes annual exercises, examples to demonstrate consequences, fre- quent reminders and bulletins/briefings (Fig.3).

In the observed sample, eleven infections out of the twenty-six were initiated by the user. An employee from LawEnfJU, for example, shut down the machine after receiving a ransom note and loggedonto several others(one-by-one) hopingto solve the problem, butinstead infectedmany morenodes onthe network. RelOrgJ said that their infection was initiated by a senior indi-vidual who had little security education and was not as com-petentwith computersasyounger colleagues. Anemployee from LawEnfMfailedtorecognisetheobvioussignsandopeneda mali-ciousemail;theExecutivePoliceOfficersubsequentlyrealisedthat their onlinetrainingwasineffectiveandreplaced itwith face-to-faceeducationfocusinguponsocialengineering.Followingthis in-cident, employees at LawEnfM regularly receive ‘call and verify’ warningstocontactITbeforeopeninganysuspiciouscontent. Sev-eral interviewees emphasised the importance of using examples of cyber incidents during training, clearly demonstrating conse-quencesfororganisationsandemployees.ITandsecuritypersonnel from LawEnfM, LawEnfJ, and GovSecJN issue periodical bulletins as a measure to increase employees’ awareness regarding new threats.

The IT/Security Manager from GovSecJ made the important point that security education isa continuousand also a gradual journey;itshouldbeginduringaninductionprocesswithaninitial introductiontosecurityconceptsandcontinuethroughout employ-ment to maintainsecurity knowledge. By making education pro-grammes relevantandemphasisingthat certain threatsmayhave knock-oneffectsonemployees’familymembers,willhavepositive influenceontheir attitudestowardssecurityandleadto security-cautious behaviour atwork.Additionally,the IT/SecurityManager fromGovSecJ recommendedannualpracticalexercisesforstaff at alllevels.

TheIT/SecurityManagerfromGovSecJNstressedthatoneofthe most challenging aspects of continuous security education is at-tractingtheusertoreadsecurity-relateddocuments:

“Youhavegot toattractpeople toread thedocumentbecause theyareallverybusy.Youcannotjustsay,‘Bewareofmalware’. Because peoplegetbored andthey willnot readit. Webegan sendinglotsofbriefingsoutwhichhadsongnamesinthetitle. And itbecamea thing… sopeople wouldlookout forit.And go,‘OhIknowwhatthatsongis.’Soundssilly,butitworked.” Thevalueofsecurityeducationismanifoldintheacademic lit-erature, for example, Connolly et al. (2017b) found that security educationincreasesemployee securityawareness andasa conse-quence,security-awareemployeesaremorelikelytofollowformal controls.HovavandD’Arcy(2012)andBulgurcuetal.(2010)found thatsecurityeducationcanreducethelevelofinformationsystems misuse.Barlowetal.(2013)observedthatmanagingemployee se-curity behaviour througha variety of trainingmethods is impor-tant. Varietyisimportantbecause thepurposeofsecurity educa-tionistoexplaintoemployees how toprotect vitalorganisational assets and why certain rules must be in place (Connolly et al., 2018).The ‘why’ isparticularlyvital becauseifemployees donot

understandthesignificanceofacertainrule,theymaynotbeable tojustifythe extraeffortthey needtomake tofollowit through and will violate security requirements. Security education must alsobe repeatedifthere areanychanges inrules andpoliciesin orderto ensure that employees keep abreast withorganisational requirements(Connollyetal.,2018).

4.1.2. Technical measures

Despiteongoingsecurityawarenessandeducationprogrammes, GovSecJN andHealthSerJUreported that employeesoftendidnot recognisemaliciousemailssenttotheirinboxesandsubsequently infectedthenetwork.Inone particularinstance,anemployeewas doubtful about opening an emailbut in the enddecided it was legitimate,onlyto open amalicious attachment.Several intervie-weesexplainedthathumanerrorneedstobeconsideredbut tech-nicalcontrolsarerequiredtosupportusers:“no matterwhatany organisationdoes, withall the traininginthe world, ifyou send enoughemailstoanorganisationwithanexciting looking attach-mentforsomeonetoclickon,someonewillclickonit” (Detective Sergeant,CyberBL).Moreover,“ifyourelysolelyonuserbehaviour, youaregoingtogetinfected… Itisabouthavingtechnicalcontrols inplace to supportthe user. And givingstaff tools to spot mali-ciousemails” (IT/SecurityManager,GovSecJN).Anumberof techni-calmeasures werealsosuggestedbyrespondents,including email hygiene, backup and recovery procedures, centrally-controlled vulner- ability management andupgrades, detection and monitoring ,and web protection (Fig.3).

4.1.2.1. Email hygiene. The IT/Security Manager from HealthSerJU reportedimprovements relatedto email hygiene, following mea-sures introduced after a user opened a malicious email and in-fected the network. The measures blocked certain links and at-tachments and put identifiers in the header of emails coming fromexternalsources.Similarly,LawEnfJstartedusingamalicious codeanalysisplatformtochecksuspiciousemails.Therespondents agreedthatalthoughemailhygienewillnotstopeverysingle ma-liciousemail,itwillfilterout themajority ofthem.Mohurleand Patil (2017)notedthat emailisthe mostcommonsourceof ran-somwareinfections,thereforefiltersmustbeimplementedtoavoid maliciousemailsreachingusers’inboxes.Prakashetal.(2017) ad-visedthemanual scanning ofemailscontaininglinksand attach-ments,eveniftheyseemtocomefromanauthenticuser.Referring toLocky attacks,Prakashetal.(2017)stressed thatoffenders can easily spoof an emailaddress to mislead users as to the source. But modern workplaces demonstrate challenging conditions that involvepressingdeadlines,therefore,employeesmaynothavethe time to query an emailthat looks legitimate andwill often just clickonalinkoranattachment.Organisationsshouldtherefore as-sumethatevery maliciousemailthat makes itswaytoemployee inboxwillbe openedandplantheimplementationofappropriate measures. Hence, relying solely on emailhygiene is not effective toprotectorganisationsagainstcrypto-ransomwareandadditional technologicalmeasuresarerequired.

4.1.2.2. Vulnerability management. The respondents also reported that crypto-ransomware managed to take advantage of various softwarevulnerabilities.Consequently,GovSecAandLawEnfJU im-plemented a centrally-controlled patching regime of all network devices,including software andhardware updates. LawEnfJU ad-ministeredmandatory updateswithin24h ofreleaseand recom-mended – within 30days. EducInstF made a decisionto remove Flashfromusers’machines.TheNCSC(2016)recommendsthat or-ganisationsperformanautomated vulnerabilityassessmentofthe entireITestateonamonthlybasis.Patchesshould beapplied ac-cordingtothelevelofseverityofvulnerabilities.Choo(2011), how-ever, stressed that many commercial off-the-shelf products form

thebackboneofmanyexisting systems,butalsocontain multiple security vulnerabilities. Jwalapuram (2018) argued that although considerableeffortscouldbemadetodevelop‘bug-free’ software, inpractice it is not easily achievable. Subsequently, it is reason-abletoexpectthatorganisationcannotpossiblypatcheverysingle vulnerability andneed to invest substantial resources (for exam-ple,timeandmoney) intoappropriate vulnerabilitymanagement. Attackers,ontheotherhand,havetofindonlyonevulnerabilityto initiateasuccessfulattack.

4.1.2.3. Upgrade management. Upgrade management was high-lighted by GovSecA and SportClubJ – these organisations had implemented a system to centrally manage upgrades after ran-somware penetrated networks via old machines. The watershed WannaCryattack demonstratedthecriticalimportance of upgrad-ingsystemsso,upgradesmustbeassessedandmanagedcentrally andona regular basis. The NCSC (2016),however, warnedabout realworldlimitationsthat preventregularupgrades.Inparticular, upgradingiscostlyandmaydisruptbusinessoperations.Moreover, certain systems may work differently after upgrades, presenting riskstobusiness operationsandsome specialistapplications may not be able to operateon upgraded systems at all. An Executive Manager disclosedthat some legacysystems atHealthSerJU can-notbeupgradedandthereforerequireextraprotectionifever con-nectedtotheInternet.ITspecialistsadvisekeepinglegacysystems onheavily-protectedsub-networksor,ifpossible,permanently of-fline.

4.1.2.4. Advanced monitoring and detection. Our respondents indi-cated that several ransomware incidents occurred due to insuf-ficient or lack of monitoring and detection controls, including AV software and firewalls. Learning from mistakes, HealthSerJU implemented AV systems with an advanced level of protection, LawEnfJswitched toacloud-based modelwheresecurityupdates are centrally-managed and EducInstF upgraded an AV solution fromsignature-basedtobehaviour-based.HealthSerJUandLawEnfJ alsoinstalledadvanced monitoringanddetectionsoftware,which proactively feeds information about any new threats and alerts businesses,allowing themtotakeactionbeforeattack campaigns. Moreover,HealthSerJUreplaceditsoldfirewallswithadvanced ver-sions that provide a higher level of protection andGovSecJN in-stalledsoftware thatcan recognise andblock maliciousIPswhen ransomwaretriestoconnectbacktothecontrolserver.

AV software is primarily designed to prevent, detect and re-movemalware.Atbestit mustofferanadvanced levelof protec-tionbeyond signature-based inorder to detect unknown threats. However, not all AV software are the same. Nevertheless, Al-rimy et al. (2018) found that even advanced detection methods haveflawsandransomware maystill remainonthe network un-detected. Sukwong et al. (2011) stressed that users must take precautions before downloading or opening any unknown files.

Kaspersky(2018)notedtheadvantagesofcloud-basedAV, includ-ingautomatic updatesandareducedamountofprocessingpower requiredtokeepthesystemsafe,comparedtothelocallymanaged AV.Severalleadingsecurityvendorshavedeveloped AVsolutions withdedicatedransomwareprotectioninplace,thoughtheir effec-tivenessisunknown.

Firewalls areused tofilterincomingtraffic andcanbe config-uredtoalloworblockpacketsfromspecificIPaddressesandports.

Sophos(2017)stressedthatmodernfirewallscaneffectivelydefend against ransomware attacks,for example, a sophisticated firewall mayincludean IntrusionDetectionSystem(IDS)thatprevents at-tacks like WannaCry and NotPetya by performing a deep packet inspectionandblockingnetworkexploitssuch asEternalBlue.The IDScan also recognise connections with malicious IPsand cause

routersto terminate them.Tosupport a useratthe network en-try, a firewall may include a sandboxing technology that identi-fiessuspiciousfilesatthegatewayandsendsthemtoasafe loca-tionforbehaviouralanalysis.However,Saådaouietal.(2014) cau-tioned that the effectiveness of firewalls mainly depends on the quality of configurationand hencea formal approach to manage firewalls is required. Generally, maintainingfirewalls necessitates specialised knowledge. Furthermore,Moore(2010) warned that a firewallisnotanultimatesolutiontosecuritythreats;itissimply oneofmanytoolsinabroadercybersecuritytoolkit.Although re-searchondetectionisongoing andassuring; organisationsshould notsolelyrelyondetectiontechnologiestoprotectagainst crypto-ransomware.

4.1.2.5. Backups and recovery. Our respondents stressed that ef-fective backup practices are essential to save organisations from a lengthy recovery and even bankruptcy. These include regular backup procedures, maintenance of backups in online and of-flinelocations,frequenttesting,andprocessesthatensurea struc-tured recovery, for example, according to the level of criticality of data and applications. EducInstFB, LawEnfM, LawEnfF, ITOrgA, and ITOrgJL all paid the ransom demand because of their inef-fective backupproceduresandcriticaldata/applicationsbeing en-crypted.Incontrast,LawEnfJ,GovSecJN,GovSecJ,EducInstF, Health-SerJU, CloudProvJL, InfOrgJL, RelOrgJ successfully recovered from crypto-ransomware because they had backups: “What helped us was that we backed up our data up. That ultimately saved our skin.” (IT/SecurityManagerfromGovSecJN).

Reflecting on past experiences, the interviewees shared their knowledge relevant to effective backup procedures. For example, the Executive Police Officer from LawEnfM brought attention to faultybackups,whereonlypartsoffileswerebackedup.Thiswas adevastatingdiscoveryduringtheattack,whichforcedthevictim to pay the ransom. Following the incident, the organisation im-plementedfrequentbackuptestingprocedures.MostofGovSecA’s backups were retained locally and thesebecame encrypted dur-ingtheattack.Theorganisationsincemovedtoabackupsolution that includesboth onlineandofflinelocations. ConstrSupJ admit-tedfiringtheirexternalITproviderforfailingtomaintaineffective backups,however,anExecutiveManagerfromEducInstFBwarned: “Backupsarenotlikefairydust… Youdonotjustpluginabackup andsuddenlyeverythingisupandrunningandyouaredoingwell. Recovering from backups is a lengthy process.” But, backing up dataisacomplexprocessthatalsorequirespreparation.

The importanceofbackups hasbeenstressedin theacademic literature(KumarandKumar,2013)astheyrepresenttheonlyreal lineoftechnicaldefenceagainstcrypto-ransomware (afterthe in-fectiontakesplace).Backups mustbe recent,regularlytested,and keptinlocationsinaccessibletoransomware(Al-rimyetal.,2018). Maintaining backups is more challenging inlarger networksand adoptingaclearrecoverystrategyisamust.

4.1.2.6. Web protection. Respondents recommended additional measures such as web filters and protection of public-facing websites.Webcontentfiltertoolsaimtopreventemployeesfrom accessingwebpagesthatmaypotentiallycontainamalicious con-tent.Althoughtheyareeffectivebecausetheyrestrictweb access, even legitimate sites could become a source of infection aswas thecasewithGovSecJandEducInstF,whereanemployeevisiteda legitimatebutinfectedwebsiteandcrypto-ransomwarepenetrated thenetworkviadrive-by-download.Besides,webcontentfiltering isnotasuitablemeasureinresearch-intenseorganisations,where employees could be prevented from doing their work. Website configuration and vulnerability scanning software can scan web contentforvulnerabilitiesandsubsequentlyincreaseprotectionof public-facingwebsites,however,aswithalldetectiontechnologies,

the problem of newly-emerged vulnerabilities and continuously changingthreatlandscaperemains.

4.1.3. Network security

Unprotected networks allow crypto-ransomware to propagate and infect a large numberof nodes. Severalvictims experienced attacksthatledtodramaticconsequencesduetonetworksecurity issues, including weak network infrastructure, inappropriate access control management and inefficient maintenance of the RDP (Fig.3). 4.1.3.1. Network infrastructure. Intervieweeshighlighted several is-sues which weaken network infrastructures, including poor net-work visibility, flatnetwork structure, inappropriate naming con-ventions,unnecessary-largeITestatesandinappropriatebackup lo-cations. The Executive Manager from EducInstFB,an organisation that is distributed across dozens of buildings, admitted that an overall lackofnetwork visibilityresultedin severeconsequences, includinghundreds ofinfecteddevices,largevolumesofsensitive data beingencrypted andparalysed critical systems.Prior to the attack, an unlimited number of deviceshad an unrestricted per-missiontoconnecttothenetwork,makingthesedevicesinvisible. Consequently,theITdepartmentwasnotabletoidentifyallthe lo-cations ofcrypto-ransomware orassesstheextentofthedamage. Ultimately,theymadethedecisiontopaycriminalsandwhilethe majorityof dataandsystemswere restored, therecovery process waschallengingandlastedformonths.

A lack of network visibility is a common problem and

Gigamon (2017) warned that two thirds (67%) of organisations have network blind spots, particularly in very large networks, wheremaintainingvisibilityisincreasinglydifficult.Security chal-lenges increase whenthere isa lack ofproper networkvisibility. More specifically, unaccountednetwork nodesmay containmany vulnerabilities, making an organisation an easy target for cyber-criminals. Subsequently, threat detection on so-called ‘invisible’ machinesisimpossible.Potentially,anattackercanpenetrate net-workviathe‘invisible’machineandstayundetectedforprolonged periodsoftime,assessingnetworktopologyandcarefullyplanning subsequentactions.Althoughmaintainingnetworkvisibilityis es-sential,itiseasiertobeachievedinthesmallerITestates. Virtual-isationisapotentialsolutionto‘in-house’hardwaremaintenance, however,cloudcomputingpresentsmanydistributedsecurityrisks (AhmedandHossain,2014) whichmust beprudently assessed.A properly documented IT estatewill also increase theoverall net-work visibility, so network segmentation becomes an important security measure asa properly segmentednetwork will make it more difficult for attackers to spread infection (US-CERT, 2016). GovSecA, forexample,experienced asubstantial attack, inwhich crypto-ransomware spreadto over 100 servers and infected crit-ical systems.The IT/Security Manager acknowledgedthat the flat network structureallowed thethreatto propagatetosuch an ex-tent.Althoughnetworksegmentationaimstoisolatesensitivedata and systems, and can potentially save millions in cyber-attacks (Guta,2017),thearchitecturerequiresspecialistknowledge andis costlytoimplementandmaintain.

Otherissuesrelatedtopoornetworkinfrastructureinclude un-necessarilylargeITestatesandinappropriatebackuplocations. Af-ter theywere attacked,the managementatGovSecArealised that numerousvulnerableserverswerenotevenservingaspecific pur-posewithin theorganisationandremovedthem.Furthermore,an employee from RelOrgJ was able to work from a backup loca-tion demonstrating that the system was not properly set up by IT professionals.Asa resultofthisoversight,the machinegot in-fected and the crypto-ransomware also encrypted backups caus-ing the IT team to restructure the network accordingly in the recovery.

Finally,ITOrgJLexperiencedasemi-targetedransomwareattack viaavulnerableRDP(asmentionedinSection4.1.3.3).Onceinside thenetwork, theattackers manually evaluatedits topology, gath-eringvery sensitiveinformation.Dueto weaknamingconvention practices,attackers swiftlyidentifiedtypes ofservers onthe net-work. Morespecifically, the organisation namedtheir servers ac-cordingtofunctionality,forexamplethebackupserverwasnamed ‘backupserver’, the email server – ‘email server’, andso on. Al-though the attack occurred as a result of a combination of fac-tors,thisparticularweakpracticegaveattackerstheadvantageof time.

4.1.3.2. Access control management. Inadequateaccesscontrol man-agementallowssomevariantsofcrypto-ransomwarelateral move-mentacrossinfectednetworkscausingdevastatingoutcomes.Such infections have far greater impact on organisations than attacks on individual systems. An IT/Security Contractor at GovSecA re-portedthat many employeeswere given administrative rights to systemsthey shouldnothaveaccessto,andweakpassword prac-ticesexposedtheorganisationtoaparticularlyharmfulattack, al-lowingattackerstoescalateprivilegesonthenetwork.Duringthe recovery process,the organisationimplemented severalmeasures tostrengthennetworkdefences.Morespecifically,employees’roles andresponsibilities were reviewed and documented, and an ad-ministrative access was granted appropriately. Two separate ac-countswere setupforadministrators;one underregularuser se-curitycontextforday-to-daywork,andanotherforadministrative tasks.Whilstthisis amajor inconvenience forallusers involved, itis anecessary securitymeasure.Furthermore,operation manu-alswere developedforeach business application, clarifyingroles, responsibilities,and,subsequently,thelevelofaccessforeach em-ployee,includingseniormanagement.

4.1.3.3. RDP maintenance. ITOrgA, ConstrSupA, EducOrgA, ITOrgJL, CloudProvJL,andConstrSupJwereinfectedduetoweakRDP prac-tices.RecoverymeasuresthereforeincludedRDPwhitelisting, dis-ablingRDPwhen notinuse,employingalternativesolutionssuch asVirtualPrivateNetwork(VPN)andappropriatepassword proce-dures(for example,usingstrong andavoiding defaultpasswords, changing passwordsfrequently). The Detective Sergeant from Cy-berBL explained that people do not realise that having the RDP turned on is unwise. They tend to use RDP once or twice for a specificpurposethenneverturnitoff:

“… Itisbesttoswitch off RDP.Orevenifyouwere tochange theport number tosomething justrandom,then it wouldbe much harderto identify. Butif you use it on its defaultport andleave it switched on, you are introuble … and what we haveseen isthat approximately50% oforganisations attacked viaRDPhadpassword‘password1’.Inapproximately25%ofthe cases,theadminpasswordwasthesameastheusername.So, iftheuserwascalledBob,thepasswordwasBob.”

AlthoughRDP offers some advantagescompared to VPNs, the drawbacksmustbeunderstood.Some VPN solutionsallow touse multi-factorauthenticationandmultipleports,whileRDPdoesnot support that. Moreover, a usercan lock down credentialswitha certificateofauthentication.Therefore,evenifanattackerobtained usernameandpassword,accesstonetworkwouldbedenied with-out an appropriate security certificate. Notonly is the VPN’s en-cryptionisstrongercomparedtoRDP,VPNsdonotsufferfromas manysoftwarevulnerabilitiesastheRDPandconnectionsviaVPNs enableamore secureremote access. Whenset up correctly,VPN allowsaremoteaccesswithoutexposingtheworkcomputertothe entireInternet.RDP, ontheother hand,becomesvulnerable once theconnectionisestablishedandport3389isopened.Itis impor-tanttonotethatRDPenablesaccesstothecomputer,whereasVPN

enablesaccesstothenetworkandcreatesamoresecure environ-ment(Scott,2017).

Keeping networks secure is a challenging task and, as with technical controls, it requires appropriate funding and highly-skilled specialists who can carefully weigh risks against benefits andsuggestoptimalsolutions.

4.1.4. Security policies and secure practices

Manyransomwareattackshappenedbecauseofweak organisa-tionalsecuritypoliciesandpractices whichmadeiteasierfor of-fenders.AnemployeefromLawEnfJU,forexample,wasawarethat somethingwaswrong,butunsuccessfullytriedtofixtheproblem aloneratherthanimmediatelyreportthesuspectedmalicious ac-tivitytoITservices.Asaresult,severaladditionalsystemsbecame infectedandtheopportunity to stop theattack waslost. Follow-ingthis incident,LawEnfJU implemented arequirementto report suspiciousactivitiesimmediately.

LawEnfJ,GovSecA,EducInstFB,HealthSerJUandConstrSupJwere all attacked on a weekend. Such timing gives offenders the op-portunitytoreconnoitrenetworktopology.Certainvariantsof ran-somwarecan alsostay dormantonthe networkforan unlimited period,untildevices ina ‘sleep’ mode are turned onby users. A DetectiveConstablefromCyberBRsaidthat:

“Weekend isa goodtime forcriminals totarget anycompany becauseeverybodyleavesworkat4o’clockonaFridayanddo not come back to workuntil Monday. Especiallytargetingthe server attheweekendisgood,because youhavenot got staff intotryandmitigateanyproblems.”

EducInstFB shared their experience of not shutting down de-vices:

“The other vulnerability that created an open door for ran-somware is people not shutting down at the end ofthe day. We all do that. Following the investigation, we did find that this particular ransomware was taking advantage of devices that wereasleep.Onceransomwarefoundsuchdevices,itwas stayingdormantuntilsomebodywokeupthedevice.Thispoor practice createdan open doorbecausewe hadmanydormant devices.Ifthey hadbeenactually trulyshutdown,theimpact oftheattackwouldnotbeassevere.”

Theaffectedorganisationssubsequentlyenforcedarule requir-ingemployeestoshutcomputersdownattheendofeachworking day.Inaddition,reminderstoshutdown computerswere sentto allstaff onFridaysandpriortoholidayfestivities.

LawEnfJ had several partnerships with other organisations, which involved sharing some systems, including email applica-tions.An employee fromLawEnfJreceived a maliciousemail into oneoftheexternalpartner’sinboxandopeneditontheLawEnfJ’s network. An investigation revealed that the partner-organisation didnot haveappropriate email hygiene.Subsequently, thevictim instigatedaformal agreementwithallexternalpartnerson mini-malsecuritymeasuresnecessarytoprotectLawEnfJ’snetwork.

A thorough investigation at EducInstF and LawEnfJU revealed thatemployeesusedcomputersforpersonalreasons,which effec-tively led to infections. While EducInstF did not implement any changes since thenature of the business wouldnot allow to re-strictusers’browsinghabits,LawEnfJUchangedthepolicy accord-ingly.

Following a ransomware infection, the IT/Security Manager from LawEnfJU implemented practices such as checking security logson adailybasis andregularly scanningall installed systems. Furthermore,EducInstFBandGovSecAenforcedstricterrulesin re-lationto passwordpractices, obliging employeesto createstrong passwords, change them frequently, use different passwords at homeandwork,andkeeppasswordssafe.

Several respondents shared that post-attack changes to secu-ritypolicieswere necessary,leadingtoimprovedsecurepractices. A security policy definesrules and guidelinesfor theproper use oforganisational IT resources (D’Arcy etal., 2009). Implementing securitypolicies inorganisationsisvitalforseveralreasons.First, policies outline rules but also consequences of disobeying these rules. Therefore, policies are viewed as a form of formal sanc-tions. Prior research demonstrates that sanctions positively influ-ence behaviour in organisational settings (Bulgurcu et al., 2010).

Connollyetal.(2018),however,warnedthatthesimple existence ofsecuritypolicies willnot havethedesiredeffect.Policiesmust be visible,up-to-date, easy to follow, properly enforced and tai-lored to a specific organisational environment oreven a depart-mentinlargerorganisations.Themostcommonwayofpromoting policiesisviaeducationandawarenessprogrammes.

Followingtheir ransomwarevictimisation,LawEnfJ,EducInstFB, LawEnfM, LawEnfJU, ITOrgA and ITOrgJL updated their organisa-tional security policies and practices. The measures included a mandatory reporting of suspicious activities, shutting down of devices at the end of the day, business-only use of computers, secure pass- words, security logs and systems scanning , and formal agreements with partners (Fig.3).

4.1.5. Incident response strategy

Our respondents indicated that the presence of an effective incident response strategy had a direct impact on reducing the consequences of ransomware attacks. The incident response ap-proaches vary in different organisations but typically the strat-egyrepresentsasuiteofdocuments.Ourintervieweesspecifically broughtto our attentionthe communication plan , the incident re- sponse plan andthe business continuity plan (Fig.3).

4.1.5.1. Communication plan. GovSecJN and LawEnfJ reported that attentionfrommedia andsecurityvendorshadanegativeimpact ontherecoveryprocess:

“Vendorsandmedia, trying toget aholdof us,created ‘com-municationwildwest’… Theycreatedalmosttheirown denial-of-service becauseIwastrying todo work[recover from ran-somwareattack] andIwasconstantly gettingphonecalls and emails…andpeopleturningup.DealingwiththatmeantIcould not deal with the fallout of the crypto-ransomware attack.” (IT/SecurityManager,GovSecJN)

Respondents also warned that not only does media attention hampertherecoveryprocess,butitisimportanttoavoid misinfor-mationinmedia:

“Themedia gruesomelyexaggeratedtheransomamount[from three-digitfiguretoseven-digitfigure].Andwithinhalfanhour IhadfivePoliceOfficersonthedoorstepbecausetheythought wewere subjecttoan ongoinglivefraudorbribery.Andalso, vendors…Andthatwasreallydisappointingactuallybecausewe expectsecurityvendorstotryandestablishfact.Anditjustdid not help because what the effect was – we were overloaded withdifferentparties contactingus…Employeesspent a lotof thetimeworryingaboutwhatisgoingtobesaidinthepress.” (IT/SecurityManager,GovSecJN)

Following these experiences, the respondents made several changestotheircommunicationplans;forexample,theIT/Security ManagerfromGovSecJNdesignatedapersontodealwithexternal stakeholdersduringtheir ongoingcyber-attack. In large organisa-tions,acommunicationteamisusuallyformedforsuchpurposes. GovSecJN also considered a switchboard to filter calls. Although EducInstF warned about being extremely cautious with wording themessagestotheoutsideworld,LawEnfM andEducInstFB sug-gestedthatitisimportanttobetransparentwiththeinformation

onsecuritybreaches:“AndIcantellyouoneofthethingsthat re-allybothersmeaboutall ofthis– whenpeople keepthisbehind closeddoors,Ithink thatwe aregivingtheadvantage tothebad guys” (ExecutiveManager,EducInstFB).

LawEnfMaddedthat onceasecuritybreachbecomespublic,it is reasonableto expect numerous external parties to contactthe victim. However, being reluctant to disclose will only exaggerate thelevelofhype:

“MyphilosophyingeneralistoletthemediaknowwhatIcan before they cometo me. The interest willdie down sooner if we share… Themediawasinterested,so wesent outapress release telling them what had happened in general. And, of course, that generatedsome response. ButIthink froma tac-ticalperspectivewewereabletobettercontroltheinformation thatgoesout.” (ExecutivePoliceOfficer,LawEnfM)

Another important aspect of the communication plan is in-forming staff throughout the organisation about the attack, in-cludingregularemployeesandmanagement.GovSecJandGovSecA did nothave a clearstrategy inplace thattakes inconsideration IT resources being down, including email. GovSecJ relied on the Internet-dependent telephone line and the communication plan did not include mobile numbers of senior management. Subse-quently,thecommunicationchannel withexecutivestaff was bro-ken and some big decisions had to be madewithout consulting toplevelmanagement.GovSecJandGovSecJNwarnedthatarobust procedureisnecessarytoinformallstaff acrosstheorganisations: “The cascadeapproach is very useful [top-downmethod], where you text top level managers first,then they text to middlelevel managers…and so on until everybody is informed.” (IT/Security Manager,GovSecJN)

Priortotheattack,allstaff atEducInstFBhademergency appli-cation installed ontheir mobile phones. Theapplication hadtwo channels – one to notify employees and a separate channel to communicate with senior leaders.Such proactive communication methodallowedtonotifystaff immediately.AnExecutiveManager from EducInstFBalso warned aboutthe importance ofinforming employeesaboutcrypto-ransomware attacksdueto thenatureof thismalware.Morespecifically,themajorityofcrypto-ransomware variantsare abletopropagate onnetworksandcertain actionsof employees can stimulate the spread (for example, turning on a ‘sleeping’device).Besides,theExecutiveManagerfromEducInstFB shared that informed staff can become instrumental to a robust recovery. In this case, they put up posters stating in prominent places “Please Do NotTurn OnOr Wake Up Your Computer” be-cause“we wereatrisk thatanybodywho cameinwokeup their computercouldhavethepotentialthatthisthingwaslyinginwait tolockyoudown.” (ExecutiveManager,EducInstFB).

4.1.5.2. Incident response plan. LawEnfJ,GovSecJN,HealthSerJU and EducInstFB commented that the incident response plan must in-cludeamethodicalresponseto thecrypto-ransomwareattack, in-corporatingclearly-documentedprocessesandanaccurate descrip-tionofresponsibilitiestomakevitaldecisions:

“An awful lotof lessons were learntfollowing the attack. We have completely redesigned ourmajor incident response plan aspartofthis.Thereisnothinglikealiveincidenttotestyour processes andmostofourprocesses workedwell butalotof themwereundocumented.Thereisalotmoreformalisationof our major incident action plan now. There is a lot more pro-cessesandpolicieswhichbackallofthatup.” (IT/Security Man-ager,HealthSerJU)

AnIT/SecurityManagerfromGovSecJalsoadvisedtodocument alldecisionsmadeduringtheattack.Sometimesdifficultdecisions must be madeinstantly andlateron accountedfor.For example,

following the attack, GovSecJ disabled the Internet access across the whole organisation in order to prevent infection spread. Es-sentially,thisdecisionhadanegativeeffectoneveryuserbecause majorcommunicationchannelslikeemailandtelephonywerecut off.Documentingthesedecisionsandthereasons whytheywere madeisvitalasseniormanagementwillseekanexplanationasto whysuchdrasticmeasuresweretaken.

Furthermore,theExecutiveManagerfromEducInstFBadvisedto createacostaccountduringongoingincidents:

“Atthetimeofthecrypto-ransomwareattack, wehadanother ongoingmajorevent.Wesetupseparatecostcontrolstructures to ensure that anyrelated costs were going into one specific bucketsothat when itis timeto getthe reimbursement,you donot haveto doa majorreconciliation. When time came to file our claim with our insurer, we just picked up those iso-latedcosts.Wedidnothavetopayateamofaccountantstogo throughthousandsofinvoicestotryandseparatethem,sothat wasveryimportant.”

4.1.5.3. Business continuity plan. Theincident responsestrategy at GovSecAhadnumerousscenariosrelatedtodifferentdisasters(for example,industrialaction,environmentalevents)butnota cyber-attack with the loss of IT. Such oversight led to the inability to servecustomersandhinderedarecoveryprocess,forexample,one “organisationhadbusinesscontinuityplansinplace,butthe sce-narios were regional emergency scenarios or environmental sce-narios. Theydid not havea scenario in place fora cyber-attack, whichgreatlydeterioratedtherecoveryprocess.” (IT/Security Con-tractor,GovSecA).TheIT/SecurityManagerfromGovSecJNstressed that business continuityshould be coordinated withtheincident investigation. An effectiveinvestigation of a cyber-attack aims to findthesourceoftheattackandclosedownall vulnerabilitiesto preventfurtherattacks.

Ahmadetal.(2012)stressedthatitisinevitableforan organi-sationthat has an Internet connection and uses informationand communication technologies to suffer a security breach at some stage. Anderson et al. (2012) noted that although a lot of mea-sures can be taken to prevent and mitigatesecurity incidents, it isnot economicallyfeasibletofullyprotectallsystems.Therefore, organisations need to be prepared and react appropriately when cyber-attacksstrike(Tøndeletal., 2014).Althoughan incident re-sponsestrategy is acomplex matter reflectedin asuite of docu-ments(forthecomprehensiveguidelinespleaserefertostandards outlined by ISO/IEC 27035), we specificallyfocused inthis paper onthecommunication, incidentresponse andbusiness continuity plans(asadvisedbyrespondents).

4.2. Enablers of change

The enablers of change (front-line and senior management ) rep-resentagroupofemployeeswhomustensuretheorganisationis preparedforcyber-attacks(Fig.3). Thefront-linemanagers (inter-changeablyreferredtoasmiddleormid-levelmanagers)havea re-sponsibilitytoimplementandmaintainappropriatesecurity mea-suresin organisations.In order to achieve thisgoal, they are re-quiredtoconvinceseniormanagementthatITandsecurityarethe toppriorityfortheorganisationinordertoobtainfunding.Onthe other hand,the functionof seniormanagement is to ensurethat theorganisationisreadytorespondmethodicallytocyber-attacks byoverlookingITfunctionandmakingoptimaldecisionsregarding securityfunding(Fig.3).

4.2.1. Front-line management

Ourrespondentssuggestedthatfront-linemanagersmust pos-sesscertain skillsandabilitiesto befitforthetask(Fig.3).First,

management is requiredto be knowledgeable in the area of secu- rity and IT in general .Second,the effective utilisation of external and internal resources is a must skill.Third, front-linemanagement is responsiblefor harvesting certain cultural traits and attitudes in or- ganisations inordertopromotebehavioursthatcompliment organ-isationalsecuritypriorities.Finally,organisationsneed toseek in-dividualswho arenotonlyinfluentialandareabletoinvoke nec-essarychangesbutalsohard-working,determinedandcommitted tothejob– thetrue champions (Fig.3).

4.2.1.1. Security and IT knowledge. LawEnfJ, GovSecJN, and Gov-SecJdemonstratedamethodicalandswiftresponsetothe crypto-ransomwareattackduetofront-linemanagersbeingsecurity-and IT-savvy. On the contrary, ransomware attacks at GovSecA and EducInstFBtookstaff bysurprise,leadingtodireconsequences, in-cludingalengthy recovery.The followingcommentsconfirm that front-linemanagersmustbeknowledgeableintheareaofsecurity inordertorespondeffectivelytoattacks.TheIT/SecurityManager fromLawEnfJsaid that theorganisation waswell-preparedwhen theransomwarehit: “Icreditthat alottomyknowledgein secu-ritysideofthings… WhenIgotaphonecallinformingmethatwe wereundercyber-attack,immediatelyIhadinkling aboutwhatit couldpossiblybe.Knowingwhattoexpectdefinitelyhelpedus re-coverfast.” ButtheIT/SecurityContractorfromGovSecAfoundthe oppositeinanothercase:

“There were two IT staff…they had been here for twenty years…and they left…the organisation only had desk support staff leftandtheydidnotunderstandthearchitectureoftheIT estate… and didnot haveanydocumentation tomake impor-tant decisions.Subsequently, theattack devastated the organi-sationandtherecoverywasverylengthy”.

4.2.1.2. Optimal utilisation of resources. Victimsofransomware at-tacks shared their experience on how they utilised various re-sources during attacks. Forexample, an ExecutiveManager from EducInstFBsuggestedpurchasingcyberinsurancebecausetheir cy-ber insurer also made several useful recommendations to help with the recovery process and reimbursed the victim some ex-penses. The IT/SecurityManager fromLawEnfJU shared that they hiredan externalcyber response teamto help withthe incident andtheywereabletodecryptthescrambleddata.TheIT/Security ContractorfromGovSecAsaidthattheirexternalcyberexpertwas able to stop the ransomware encryption process and the Execu-tiveManagerfromEducInstFBrecommendedengagingacyber re-sponseteamandabreachcoachbeforeanattack:

“Find a breach coach [i.e. a lawyer who specifically deals withcyber-breachesandadvisesclients],findacyberresponse team[i.e.to conductathoroughinvestigationandfindpatient zero]…get anengagementsetupwiththem,nota retainer,so there isno needto pay,justan engagement.Wewasted time trying to engage with specialists and that was really critical, andIwishwehadthisengagement.”

Severalparticipantssuggestedcautionwhenchoosingan exter-nal IT service provider. After being attacked, ConstrSupJ realised thattheexternal ITteamfailedtomaintainproperbackups. Sub-sequently,thevictim suffered severeconsequences, includingthe lossofvitalinformationandalengthyrecovery.TheExecutive Po-liceOfficerfromLawEnfMhadasimilarissuewiththeinternalIT teamanddecidedtotakethematterintheirownhands:

“Whenwegothitbyransomware,Iwasembarrassed,andIwas angry… I wasangryontwolevels.Iwasupsetthatwehad in-vitedthevirus.IwasupsetatourITfolksbecauseIthoughtwe

wereprotectedfromthis.Wehadwhatwethoughtwasan ade-quatelevelofsecurityandpoliciesinplaceforourstaff. Unfor-tunately, thebackup softwaremalfunctioned, and ourIT folks didnotpickuponit.Sincetheattack,Iperformregular cyber threatriskassessments.”

The IT/Security Manager from GovSecJN praisedthe response they received from theexternal IT provider that happened to be located nearby;thelocalpresence ofIT specialists greatlyhelped therecoveryprocess.

4.2.1.3. Cultivate culture and attitudes. IT/Security Managers from GovSecJNandGovSecJemphasisedtheimportanceofencouraging openreportingculturebecauseatimelyresponsetoransomwareis absolutelyessential.Withoutanopenreportingculture,staff worry aboutbeing subject to disciplinaryaction. It “discourages people frompickingupthephoneandtellingusaboutit.Wewantpeople totellus… everybodymakes mistakes.So,let’s moveawayfrom blaming somebody and understand why it happened and what we can do to try andreduce the risk of that happening again.” (IT/SecurityManagerGovSecJN).Buttheorganisationalculturealso hastoharvestacultureofsolidarityamongitsemployees.In high-solidarityenvironmentsemployeesunderstandandshare organisa-tionalgoals;theyarecooperative,loyal,andexpressgreat satisfac-tionandprideworkingfortheirorganisations.Onthecontrary,in low-solidarity organisationsemployeesbelieve thatorganisational problemsarenottheirproblems:“Anemployeereceivedanemail andtheyshouldnothaveclicked onit,butthey did.Therewasa certain amountofapathy.The usersaid, ‘Itdoesnot matter, itis not going toaffectme.’ Theywerenot happy withtheirworking environment.” (IT/SecurityManagerfromGovSecJ).

GovSecJN, GovSecJ, EducInstF, EducInstFB,and FinOrgJL added thatinternalstaff solidarityisalsothekeytoaneffectiverecovery. Followingattacks,peopleareforcedtoworkinchallenging condi-tions,includinglongerhours,theabsenceofmaincommunication channelsandcomputingdevices.Cultureofsolidarityisan impor-tantdriveinthesechallengingcircumstances.EducInstFBsaidthat despiteaverylong recoveryprocessanddisabledcommunication channels,employeesstayedsupportiveandhelpful:

“Whatwasveryinterestingandhugelyimportanttothe recov-eryprocessisthatwehadpeoplewithoutemail.Wehad peo-plewhocouldnotSkype.Wehadpeoplewhohadnocontacts ontheirphones.Andyeteveryone wassupportive…Istill mar-velthe fact thatwe hadnumerousransom notesandnot one wasleakedtothepressandnotonewastweetedoutonsocial media… Andit isalways good todo greatthings in thegood times,butitisprettyamazingtoseepeoplehelpinginthebad timesbecausethatreallydoessayalotaboutourculture.” (Ex-ecutiveManager,EducInstFB)

Incontrasttotheabove,GovSecAstressedthatwhilemanystaff wereincredibly positiveandwenttogreatlengthstosupportthe recovery(forexample,travellingmanymileseverydayformonths in order to continue to deliver services), there were employees who complained about difficulties in working during the recov-ery process andalso fed information to the press which fuelled stress amongstaff andhampered recovery.An ExecutiveManager fromEducInstFBstressedthat extra supportisneededto encour-ageemployees’cooperation,includingopencommunication, grati-tude,andnecessarysupplies:

“We believe in open transparent communication and we in-formedstaff immediately…If youtellpeoplewhat isgoingon, thenthey will feelthat theyare beingcaredfor,andthey are farmorelikelytobesupportive.Ifyouleavetheminthedark, first,theyaregoing tomakestuff up.Butsecond, theyare go-ing to feel very agitatedbecause nobody ishelping them