A Prospective, Randomized Trial of an Emergency Department

Observation Unit for Acute Onset Atrial Fibrillation

Wyatt W. Decker, MD Peter A. Smars, MD Lekshmi Vaidyanathan, MBBS Deepi G. Goyal, MD Eric T. Boie, MD Latha G. Stead, MD Douglas L. Packer, MD Thomas D. Meloy, MD Andy J. Boggust, MD Luis H. Haro, MD Dennis A. Laudon, MD Joseph K. Lobl, MD Annie T. Sadosty, MD Raquel M. Schears, MD Nicola E. Schiebel, MD David O. Hodge, MS Win-Kuang Shen, MD

From the Department of Emergency Medicine (Decker, Smars, Vaidyanathan, Goyal, Boie, Stead, Meloy, Boggust, Haro, Laudon, Lobl, Sadosty, Schears, Schiebel), Cardiology (Packer, Shen), and Division of Biostatistics (Hodge), Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, MN.

Study objective:An emergency department (ED) observation unit protocol for the management of acute onset atrial fibrillation is compared with routine hospital admission and management.

Methods:Adult patients presenting to the ED with atrial fibrillation of less than 48 hours’ duration without hemodynamic instability or other comorbid conditions requiring hospitalization were enrolled. Participants were randomized to either ED observation unit care or routine inpatient care. The ED observation unit protocol included pulse rate control, cardiac monitoring, reassessment, and electrical cardioversion if atrial fibrillation persisted. Patients who reverted to sinus rhythm were discharged with a cardiology follow-up within 3 days, whereas those still in atrial fibrillation were admitted. All cases were followed up for 6 months and adverse events recorded.

Results:Of the 153 patients, 75 were randomized to the ED observation unit and 78 to routine inhospital care. Eighty-five percent of ED observation unit patients converted to sinus rhythm versus 73% in the routine care group (difference 12%; 95% confidence interval [CI]⫺1% to 25%];P⫽.06). The median length of stay was 10.1 versus 25.2 hours (difference 15.1 hours; 95% CI 11.2 to 19.6;P⬍.001) for ED observation unit and inhospital care respectively. Nine ED observation unit patients required inpatient admission. Eleven percent of the ED observation unit group had recurrence of atrial fibrillation during follow-up versus 10% of the routine inpatient care group (difference 1%; 95% CI⫺9% to 11%;P⫽.93). There was no significant difference between the groups in the

frequency of hospitalization or the number of tests, and the number of adverse events during follow-up was similar in the 2 groups.

Conclusion:An ED observation unit protocol that includes electrical cardioversion is a feasible alternative to routine hospital admission for acute onset of atrial fibrillation and results in a shorter initial length of stay. [Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:322-328.]

0196-0644/$-see front matter

Copyright©2008 by the American College of Emergency Physicians. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.12.015

INTRODUCTION

Background

The prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the US population is currently estimated to be 2.3 million and will continue to increase as the population ages. By 2050, it has been projected that the prevalence of atrial fibrillation will be greater than 5.6 million.1The incidence of new onset atrial fibrillation increases

with age and is about 1% in persons aged 60 to 68 years, increasing to almost 5% in persons older than 69 years. During the past 20 years, hospital admissions for atrial fibrillation have increased by 66%2primarily because of the rapidly growing

elderly population.3 Importance

Atrial fibrillation is a significant contributor to national health care expenditures. In 2005, total annual costs for treatment of atrial fibrillation were estimated at $6.65 billion, including hospitalizations, with a principal discharge diagnosis of atrial fibrillation ($2.93 billion), inpatient cost of atrial fibrillation as a comorbid diagnosis ($1.95 billion), outpatient treatment of atrial fibrillation ($1.53 billion), and prescription drugs ($235 million).4

Diagnosis and appropriate management of this increasingly prevalent heart arrhythmia are critical because of its

complication of heart failure and stroke, which may result in high levels of functional debility or death.5The presence of

atrial fibrillation confers a 5-fold increased risk of stroke. It is estimated that 15% of all strokes may be directly attributable to atrial fibrillation. Also of concern is that a stroke episode resulting from a cause of atrial fibrillation has a worse outcome in comparison with strokes of other origin.6The Framingham Study has revealed a 1.5 to 1.9-fold higher risk of death associated with chronic atrial fibrillation, attributable largely to thromboembolic stroke.7Studies have been done suggesting that emergency department (ED) observation unit care is a feasible option in patients with acute onset atrial fibrillation in whom initial ED stabilization has been achieved.8Because current American Heart Association practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with atrial fibrillation do not advise routine anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation of less than 48 hours’ duration (or transesophageal echocardiograph) before cardioversion,9there is an opportunity for definitive treatment in the ED for these patients.

Goals of This Investigation

Our study randomized patients with acute onset atrial fibrillation presenting to the ED to the observation unit with electrical cardioversion versus routine inpatient admission to compare outcomes in care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS Setting

This prospective randomized study was performed during a period of 3 years (September 1999 to December 2002) in the ED of a tertiary referral center and was approved by the authors’ institutional review board.

Study Design

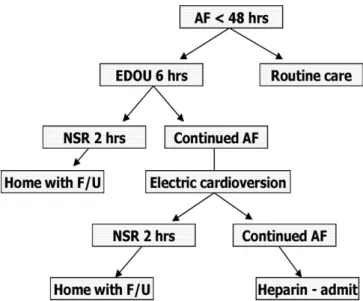

Only patients willing and able to sign an informed consent were included in this study. After granting consent, participants were randomized by telephone call to a remote, designated randomization center uninvolved in the patients’ care. Patients were then managed per the protocol to either care in the ED observation unit or routine inpatient hospital care (Figure 1).

Selection of Participants

Our cohort consisted of adult patients older than 18 years who presented to the ED of a tertiary referral center with atrial fibrillation of less than 48 hours’ duration, without

hemodynamic instability or other conditions requiring hospitalization. Only patients from the 10 local counties served by the institution were enrolled to ensure comprehensive follow-up and minimize selection bias. Less than 48 hours’ duration was established from patient history of onset of symptoms, and any uncertainty in duration was a criterion for exclusion.

Exclusion criteria for the study included atrial fibrillation of greater than 48 hours’ duration and hemodynamic instability. Those patients presenting with an unclear duration of symptoms were presumed to have had them greater than 48 hours. Hemodynamic instability was defined as any patient with

Editor’s Capsule Summary

What is already known on this topic

Hospital admissions for atrial fibrillation have increased by 66% during the past 2 decades, primarily because of the rapidly growing elderly population.

What question this study addressed

This 153-patient randomized trial compared observation unit care that included early cardioversion with routine hospitalization in patients with uncomplicated atrial fibrillation of less than 48 hours’ duration.

What this study adds to our knowledge Patients treated in the observation unit had

substantially shorter hospitalizations and were 12% (95% confidence interval –1% to 25%) more likely to be discharged in sinus rhythm.

How this might change clinical practice

Early cardioversion in the emergency department or observation unit may be a feasible alternative to hospitalization in patients with uncomplicated atrial fibrillation of short duration.

a systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg, diastolic less than 50 mm Hg, or a pulse rate of 130 beats/min or more after attempts to rate control. Known intracardiac thrombus, class IV congestive heart failure, ejection fraction less than 30%, chest pain consistent with class IV angina, acute myocardial infarction within 4 weeks before atrial fibrillation onset, stroke or transient neurologic ischemic attack in the past 3 months, previous unsuccessful electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation or active medical problems other than atrial fibrillation such as unstable angina, pneumonia, transient neurologic ischemic attacks, and strokes requiring inpatient evaluation were also excluded from this study. Patients from outside of Olmsted County or its surrounding 9 counties were not eligible for enrollment. Interventions and Methods of Measurement

The 8-hour ED observation unit protocol included recording of an ECG, chest radiograph, and routine laboratory

investigations, including electrolyte levels, CBC count, and glucose level. This was followed by pharmacologic pulse rate control using a calcium channel blocker or a-blocker. Rate control was defined as a ventricular response less than 100 beats/ min at rest. All patients received continuous cardiac monitoring and were reassessed after 6 hours. Those still in atrial fibrillation were sedated and electrically cardioverted with the Physio Lifepak 6 (Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN) (before 2001) or the Zoll M Series Biphasic Manual device (Zoll Medical Corporation, Burlington, MA) (after 2001) for correction of atrial fibrillation and observed for a further period of 2 hours. Those in sinus rhythm after the 2-hour observation period were discharged home, with cardiology follow-up arranged within 3 days. Patients who were enrolled in the study in the evening were observed overnight and cardioverted between 7 and 9AM. Study patients treated in the ED observation unit were not

given any antiarrhythmic on discharge and were not anticoagulated. Those remaining in atrial fibrillation after unsuccessful attempts to electrically cardiovert were admitted to the hospital cardiology service. All care, including initial evaluation, ED observation unit care, procedural sedation, and cardioversion, was overseen by the emergency medicine attending physician on duty.

The patients randomized to routine hospital care underwent an ECG and routine laboratory investigations in the ED. They were given an intravenous calcium channel blocker or a -blocker for rate control, began receiving a heparin infusion, and were admitted to a monitored bed on the cardiology service. ED management was at the discretion of the emergency medicine attending physician on duty.

Follow-up for recurrence of atrial fibrillation, adverse events, and further visits to the hospital was performed during a 6-month period. We used telephone follow-up, in addition to record review. The patients were contacted at 30 days and 6 months, and no patients were lost to follow-up.

Outcome Measures

The primary endpoint was conversion to sinus rhythm or rate control at the completion of initial ED observation unit or hospital stay. Secondary endpoints were recurrence of atrial fibrillation and adverse events (subsequent myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, or death). Further utilization of health care resources was measured by further recurrent visits to the hospital. All secondary endpoints were recorded during a 6-month follow-up period.

Primary Data Analysis

Factors were summarized with percentages, means, medians, and standard deviations, depending on the type of variable of interest (using SAS software, version 8.2; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Categorical factors were compared between the groups by using the2test for independence. For each of the continuous measurements, there was evidence that the values were nonnormal, so the comparisons between the groups were carried out with the Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for each of the measurements. AP⬍.05 was considered to be significant. RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Subjects

Throughout the 39-month study period, 252,392 patients presented to the ED; 2,096 of these patients were found to have atrial fibrillation, and 153 patients were eligible and enrolled to this study after written consent was obtained. Seventy-five of the 153 patients were randomized to the ED observation unit and 78 to routine inpatient hospital care (Figure 2). Reasons for exclusion and number of patients excluded are outlined inTable 1. The average age of the patients admitted to the ED

observation unit was 58⫾18 years, and 53% were men, whereas the average age of the inpatient service group was 59⫾16 years, of whom 69% were men.Table 2shows demographic

characteristics of the study population. Figure 1.Protocol for ED observation unit care.AF, Atrial

fibrillation,EDOU, emergency department observation unit;

Main Results

Of the 2 groups, 85% (64) converted to normal sinus rhythm in the ED observation unit cohort compared with 73% (57) in the routine care group (P⫽.06,2test;

difference⫽12%; 95% CI⫺1% to 25%) (Table 3). The median length of stay for the ED observation unit set was 10.1 hours and mean 12.6 hours, whereas the median and mean length of stay for admitted patients was 25.2 hours and 50.1 hours, respectively (P⬍.001, rank-sum test; difference in

medians is⫽15.1; 95% CI 11.2 to 19.6). Among the cases randomized to the ED observation unit, 24 (32%) reverted to normal sinus rhythm after pharmacologic rate control and 38 (51%) required electrical biphasic cardioversion (Table 4). 153 patients eligible enrolled Randomized EDOU Care N=75 In-hospital care N=78 2096 presentations of AF

Exclusion criteria applied 1. Duration >48 hours 2. Hemodynamic instability 3. Intracardiac thrombus 4. Class IV CHF 5. EF < 30% 6. Class IV Angina 7. Acute MI within 4 weeks 8. Stroke/ TIA within 3 months

9. Prior unsuccessful electrical cardioversion for AF 10.

11.

Other co-morbid conditions in addition to AF From outside predefined geographical area

EDOU Care (N = 75)

Inpatient care (N = 78)

• ECG, CXR, Labs

• Ventricular rate control using BB/CCB

• Electrical cardioversion

• Admit to ward

• ECG, CXR, Labs

• Ventricular rate control using BB/CCB • Electrical cardioversion Follow Up • Recurrence of AF: 11% (8) • Return visits: 33% (25) • Adverse Events: 0 Follow Up • Recurrence of AF: 10% (8) • Return visits: 35% (27) • Adverse Events: 1% (1) Converted to sinus: 85% (64) Converted to sinus: 73% (57)

252,392 presentations to the ED

Figure 2.Randomization and outcome algorithm.CHF, Congestive heart failure;EF, ejection fraction;MI,

myocardial infarction;TIA, transient ischemic attack;CXR, chest X-ray;BB, betablocker;CCB, calcium-channel blockers.

Table 1.Exclusion criteria and frequency.

Eligibility Frequency (n) Percentage

Enrolled patients with signed consent 153 7.30

Refused participation 46 2.19

Out of local county area 457 21.80

Social admission 49 2.34

Direct admission 10 0.48

Left against medical advice 1 0.05

Dismissed home from the ED 107 5.10

AF⬎48 h 197 9.40

Unstable hemodynamics in AF* 6 0.29

Class IV CHF 79 3.77

Known EF⬍30% 1 0.05

Chest pain consistent with class IV angina

140 6.68

Acute myocardial infarction within 4 weeks before AF

9 0.43

Stroke/transient ischemic attack during the past 3 mo

2 0.10

Previous unsuccessful electrical cardioversion for AF

5 0.24

Patients previously included in the study

75 3.58

Active medical problems (other than AF) requiring inpatient evaluation

338 16.13

Other 421 20.09

Total 2,096 100.00

*Systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure less than 50 mm Hg, or pulse rate greater than 130 beats/min after attempt to rate control.

Table 2.Baseline characteristics in the cohorts.

Characteristic

ED Observation

Unit Group Inpatient Group Combined

(nⴝ75) (nⴝ78) (nⴝ153) Demographics Age, y (SD) 57.5 (18.3) 58.5 (15.7) Male (%) 40 (53) 54 (69) 94 (61) Female (%)* 35 (47) 24 (31) 59 (39) Risk factors (%) Previous myocardial infarction 8 (11) 4 (5) 12 (8)

Congestive heart failure 2 (5) 0 2 (3)

Coronary artery disease/angina 15 (20) 16 (21) 31 (20) Previous atrial fibrillation/flutter 44 (59) 52 (67) 96 (63) Previous successful cardioversion 14 (19) 22 (29) 36 (24) Previous stroke 1 (1) 1 (1) 2 (1) Hypertension 36 (48) 32 (41) 68 (44) Diabetes 1 (1) 1 (1) 2 (1) Smoking 28 (37) 35 (44) 63 (41) Recreational drugs 2 (3) 1 (1) 3 (2 )

Twenty-four patients underwent spontaneous/nonelectrical conversion from the ED observation unit group, as did 34 patients in the inpatient group. The remaining cases (N⫽9) failed to meet the criteria for discharge and required inpatient admission after the 8-hour observation period. Four of these patients had recurrent atrial fibrillation after an attempt at electrical cardioversion, whereas 2 were admitted because of increased cardiac marker levels and 1 because of hemodynamic instability after successful cardioversion. Two patients denied ED observation unit care and requested admission after randomization.

During follow-up within 6 months of the study, 11% (8) of the ED observation unit group had recurrence of atrial

fibrillation in comparison with 10% (8) of the routine inpatient care group (P⫽.93,2test; difference in percentages 1%; 95% CI of the differences⫺9% to 11%). There were no significant differences between the groups in the frequency of

hospitalization, number of tests/procedures, or adverse events during their 6-month follow-up (Tables 3,4). No patients were lost to follow-up.

LIMITATIONS

The limitations involve the sample size at a single center, which may limit the ability to generalize to other patient populations. Sample size also makes it difficult to assess the risk of stroke and other major complications. Further, no distinction was made between new and recurrent atrial fibrillation and the various underlying causes of atrial fibrillation. This reflects the investigators’ desire to develop a protocol for most acute onset atrial fibrillation patients, but we recognize there are some subtle differences in these groups. A significant difference in sex between the cohorts was observed with more women in the ED observation unit group. The sex-related difference in the Rate Control versus Electrical Cardioversion (RACE) study showed that women were more likely to have a poorer outcome in the rhythm control treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation.10,11

But no disparity in outcome was observed between the groups despite the difference in distribution. Also, treatment of the patients in the inhospital arm was not standardized and was up to the discretion of the cardiologist.

DISCUSSION

ED observation units have been described as a rational choice for improving the utilization of health care resources and improving the quality of patient care.12They have been used

successfully in the treatment of common conditions such as chest pain,13asthma,14and syncope15and have been suggested

for atrial fibrillation.16We sought to determine the benefit of

observation unit management of atrial fibrillation, an

increasingly prevalent condition, over traditional inhospital care. Our study showed that the management of acute onset atrial fibrillation of less than 48 hours’ duration in the ED

observation unit was comparable to inpatient care with regard to rhythm conversion and recurrence of atrial fibrillation and adverse events (subsequent myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, or death). Though fewer patients received electrical cardioversion in the inpatient arm, the overall conversion rates were comparable. This may also be due to a function of time. ED observation unit care resulted in a shorter hospital length of stay, without any change in overall utilization of health care visits during the 6 months after enrollment.

Much attention has been given to the rate versus rhythm control strategies for chronic atrial fibrillation. The Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) and RACE studies, which included patients with longstanding atrial fibrillation, showed no significant difference in survival or quality of life with rate control compared with a rhythm control strategy. Most patients who experienced strokes in AFFIRM were not treated with warfarin or had a

subtherapeutic international normalized ratio at the stroke, and more patients in the rhythm control arm had warfarin

Table 3.Follow-up data at 6 months, with intergroup comparison.

Data

ED Observation

Unit Inhospital Difference, (95% CI) Conversion to normal sinus rhythm, % 64 (85) 57 (73) 12 (⫺1 to 25) Mean number of adverse events at 6 mo (median) 0.63 (1.0) 0.71 (1.0) ⫺0.08 (⫺0.28 to 0.12) Mean number of procedures at 6 mo (median) 1.2 (1.0) 1.3 (1.0) ⫺0.1 (⫺0.4 to 0.3) Mean number of health care visits (median) 2.9 (3.0) 2.9 (3.0) 0 (⫺0.6 to 0.5)

Table 4.Management and outcome between the ED observation unit and inpatient groups.

Treatment ED Observation Unit Group (%) (nⴝ75) Inpatient Group (%) (nⴝ78) Electrical cardioversion 38 (51) 18 (23) Spontaneous conversion

after rate control

24 (32) 34 (44) Rate-controlling agents -Blocker 15 (20) 27 (35) Calcium channel blockers 56 (75) 57 (73) Digoxin 4 (5) 6 (8) Outcome (6 mo) Recurrent atrial fibrillation 8 (10) 8 (10) Myocardial infarction 0 1 (1) Congestive heart failure 0 0

Stroke 0 0

Death 0 0

discontinued.17There was also a significant increase in fatal noncardiovascular events in the rhythm control arm in contrast to rate control.18This was suggested to be due to the increased use of amiodarone for rhythm control, which has been shown to increase noncardiac mortality.19But both of the above studies

did not examine a population with atrial fibrillation of less than 48 hours’ duration. With prolonged atrial fibrillation, there is difficulty in restoring sinus rhythm because of electrical and structural remodeling of the heart, which favors permanent atrial fibrillation. This makes it important to ensure that an attempt is made to restore sinus rhythm early in the course of treatment of a patient with atrial fibrillation.9

Cardioversion performed early after admission can successfully restore a sinus rhythm in most patients. A

retrospective study done in 2005 suggested that shorter duration of atrial fibrillation (⬍48 hours) and absence of heart failure are reliable predictive factors of a successful conversion to sinus rhythm.20A similar prospective cohort study that used ibutilide

and cardioversion in the ED for patients with atrial fibrillation less than 48 hours’ duration had results comparable to our data with respect to conversion to sinus rhythm.21Our trial

encompassed a larger cohort and was controlled to compare the efficacy of treatment. Earlier studies have also likewise

concluded that most patients with recent onset atrial fibrillation who undergo successful ED electrical cardioversion do not appear to require admission to the hospital and that immediate and short-term complications were relatively uncommon.22,23 In a prospective cohort of 1822 patients, Weigner et al24found

that the likelihood of clinical thromboembolism is 0.8% among patients with atrial fibrillation lasting less than 48 hours who convert to sinus rhythm, which supports the recommendation for early cardioversion in these patients.

Atrial fibrillation is a significant contributor to health care costs. Approximately 350,000 hospitalizations each year are attributable to atrial fibrillation in the United States. Total annual costs for treatment of atrial fibrillation are estimated at $6.65 billion, including $2.93 billion for hospitalizations with a principal discharge diagnosis of atrial fibrillation.4Therefore, an

ED observation unit management approach would play a part in reducing the annual national expense in the management of atrial fibrillation.

During the past 20 years, there has been a 66% increase in hospital admissions for atrial fibrillation2because of a combination of factors, including the aging of the population, an increasing prevalence of chronic heart disease, and more frequent diagnosis through use of ambulatory monitoring devices. Atrial fibrillation is a costly public health problem, with hospitalizations as the primary cost driver.16Considering the mean number of admissions per year, initiating ED observation unit admission and management would potentially decrease the number of beds occupied on the wards, thus increasing the availability of beds.25

Costs of care throughout the RACE study were comparable for the rhythm control, as well as for the rate control group, at

the end of the follow-up period.26Hence, an ED observation unit approach with adequate rate control in the ED setting might provide comprehensive management with a lower expenditure rate for a patient with new onset atrial fibrillation, considering the absence of comorbid conditions, acute onset, and low risk of thromboembolism.8Few prospective data are available on the management of atrial fibrillation in the ED. A retrospective study done in 1996 showed 216 patients admitted for atrial fibrillation, of which 66% met predetermined admission criteria. Their criteria for a medically justified admission included variables recorded in the ED on

presentation (hypotension with a systolic blood pressure⬍90 mm Hg; presence of comorbid condition in addition to atrial fibrillation that warranted admission, such as congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, and significant complication during ED; or inhospital stay).27

The benefits of our study include its prospective randomized nature and similarity of the groups. Inclusion of patients from only the local counties helped minimize referral bias. Thus, there might be a large number of patients eligible from outside the local counties, and our tertiary practice may have under estimated the eligible patients presenting to community hospitals.

Ideally, this study would be followed by a multicenter trial with larger patient numbers as we would like assess

generalizability. We used both monophasic and biphasic defibrillators in our trial because biphasic units were just being introduced during our study. We would have preferred to use biphasic defibrillating pulse waveforms throughout the study. Improved success rates of biphasic over monophasic

defibrillators have been published by Greene et al.28 The data suggest that atrial fibrillation management guidelines for new onset atrial fibrillation should perhaps be revisited to include an ED observation unit as an alternative to inpatient admission in selected patients presenting with acute onset atrial fibrillation. Such a protocol may reduce hospital stay and annual expenditure for this increasingly prevalent condition while maintaining the same quality and outcome of care.

In summary, an ED observational unit protocol with rate control and electrical cardioversion capabilities is a feasible alternative to inhospital admission of acute onset atrial fibrillation presentations of less than 48 hours’ duration. A multicenter trial would be helpful to assess the safety of this approach.

The authors wish to gratefully acknowledge the expert assistance of Ms. Susan Puetz, the research assistance of Ms. Ann Walker, and the patients themselves.

Supervising editor:W. Brian Gibler, MD

Author contributions:WWD, PAS, DGG, ETB, DLP, TDM, AJB, LHH, DAL, JKL, ATS, RMS, NES, and W-KS made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. DOH was responsible for

analysis of the data and statistical support. WWD, PAS, LV, LGS, DLP, DOH, and W-KS were responsible for drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. WWD takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Funding and support: By Annals policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article, that might create any potential conflict of interest. See the Manuscript Submission Agreement in this issue for examples of specific conflicts covered by this statement. This research was funded by a clinical research grant from the Mayo Foundation for Education and Research.

Publication dates: Received for publication May 21, 2007. Revision received November 1, 2007. Accepted for publication December 12, 2007. Available online March 14, 2008. Reprints not available from the authors.

Address for correspondence: Wyatt W. Decker, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, Genrose G-410, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905; 507-255-6501, fax 507-255-6592; E-mail decker.wyatt@mayo.edu.

REFERENCES

1. Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study.JAMA. 2001;285:2370-2375. 2. Friberg J, Buch P, Scharling H, et al. Rising rates of hospital

admissions for atrial fibrillation.Epidemiology. 2003;14:666-672. 3. Arias E. United States Life Tables, 2002. National Vital Statistics

Reports; Vol. 53 No: 6. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2004.

4. Coyne KS, Paramore C, Grandy S, et al. Assessing the direct costs of treating nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in the United States. Value Health. 2006;9:348-356.

5. Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Scheinman MM, Aliot EM, et al. ACC/ AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias: executive summary; a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Supraventricular Arrhythmias).Circulation.2003;108:1871-1909. 6. Lip GY, Watson T, Shantsila E. Anticoagulation for stroke

prevention in atrial fibrillation: is gender important?Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1893-1894.

7. Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1998;98:946-952.

8. Koenig BO, Ross MA, Jackson RE. An emergency department observation unit protocol for acute onset atrial fibrillation is feasible.Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:374-381.

9. Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm

Association and the Heart Rhythm Society.Circulation. 2006;114:e257-354.

10. Van Gelder IC, Hagens VE, Bosker HA, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with recurrent persistent atrial fibrillation.N Eng J Med. 2002;347:1834-1840. 11. Rienstra M, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Hagens VE, et al; RACE

Investigators. Gender-related differences in rhythm control treatment in persistent atrial fibrillation: data of the RACE study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1307-1308.

12. Roberts R, Graff LG 4th. Economic issues in observation unit medicine.Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2001;19:19-33. 13. Farkouh ME, Smars PA, Reeder GS, et al. A clinical trial of a

chest-pain observation unit for patients with unstable angina. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1882-1888.

14. Rydman RJ, Isola ML, Roberts RR, et al. Emergency department observation unit versus hospital inpatient care for a chronic asthmatic population: a randomized trial of health status outcome and cost.Med Care. 1998;36:599-609.

15. Smars PA, Decker WW, Shen WK. Syncope evaluation in the emergency department.Curr Opin Cardiol. 2007;22:44-48. 16. Raghavan AV, Decker WW, Meloy TD. Management of atrial

fibrillation in the emergency department.Emerg Med Clin North Am.2005;23:1127-1139.

17. The AFFIRM Investigators. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation.N Engl J Med. 2002;34:1825-1833.

18. Stead LG, Decker WW. Rhythm versus rate control for atrial fibrillation and flutter.Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:496-498. 19. Steinberg JS, Sadaniantz A, Kron J, et al. Analysis of

cause-specific mortality in the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) Study.Circulation. 2004;109: 1973-1980.

20. Zahir S, Lheureux P. Management of new-onset atrial fibrillation in the emergency department: is there any predictive factor for early successful cardioversion?Eur J Emerg Med.2005;12:52-56. 21. Domanovits H, Schillinger M, Thoennissen J, et al. Termination of

recent-onset atrial fibrillation/flutter in the emergency

department: a sequential approach with intravenous ibutilide and external electrical cardioversion.Resuscitation. 2000;45:181-187.

22. Michael JA, Stiell IG, Agarwal S, et al. Cardioversion of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in the emergency department.Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:379-387.

23. Burton JH, Vinson DR, Drummond K, et al. Electrical cardioversion of emergency department patients with atrial fibrillation.Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:20-30.

24. Weigner MJ, Caulfield TA, Danias PG, et al. Risk for clinical thromboembolism associated with conversion to sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation lasting less than 48 hours.Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:615-620.

25. Crenshaw LA, Lindsell CJ, Storrow AB, et al. An evaluation of emergency physician selection of observation unit patients.Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:271-279.

26. Rienstra M, Van Gelder IC, Hagens VE, et al. Mending the rhythm does not improve prognosis in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation: a subanalysis of the RACE study.Eur Heart J. 2006; 27:357-364.

27. Mulcahy B, Coates WC, Henneman PL, et al. New-onset atrial fibrillation: when is admission medically justified?Acad Emerg Med.1996;3:114-119.

28. Greene HL, DiMarco JP, Kudenchuk PJ, et al. Comparison of monophasic and biphasic defibrillating pulse waveforms for transthoracic cardioversion.Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:1135-1139.