Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=raer20

ISSN: 1814-6627 (Print) 1753-5921 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/raer20

Kenyan Secondary Teachers’ and Principals’

Perspectives and Strategies on Teaching and

Learning with Large Classes

Sophia M. Ndethiu, Joanna O. Masingila, Marguerite K. Miheso-O’Connor,

David W. Khatete & Katie L. Heath

To cite this article: Sophia M. Ndethiu, Joanna O. Masingila, Marguerite K. Miheso-O’Connor, David W. Khatete & Katie L. Heath (2017): Kenyan Secondary Teachers’ and Principals’ Perspectives and Strategies on Teaching and Learning with Large Classes, Africa Education Review, DOI: 10.1080/18146627.2016.1224573

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2016.1224573

Published online: 11 Apr 2017.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 12

View related articles

DOI: 10.1080/18146627.2016.1224573 Print ISSN 1814-6627 | Online 1753-5921 © University of South Africa Africa Education Review

Volume xx | Number xx | 2017 | pp. xx–xx

http://www.tandfonline.com/raer20

KENYAN SEcONDARY tEAcHERS’

AND PRINcIPAlS’ PERSPEctIVES AND

StRAtEGIES ON tEAcHING AND lEARNING

WItH lARGE clASSES

Sophia M. Ndethiu Kenyatta University, Kenya ndethiu.sophia@ku.ac.ke

David W. Khatete Kenyatta University, Kenya khatete.david@ku.ac.ke Joanna O. Masingila

Syracuse University, NY, United States jomasing@syr.edu

Katie L. Heath

Syracuse University, NY, United States klnichip@syr.edu

Marguerite K. Miheso-O’Connor Kenyatta University, Kenya

miheso.marguerite@ku.ac.ke

ABStRAct

the reality that teachers in developing countries teach large, and even overcrowded classes, is daunting and one that may not go away any time soon. class size in Kenyan public

secondary schools is generally 40–59 students per class. This article reports initial findings

on teachers’ and principals’ perspectives related to large classes. We used questionnaires, interviews and classroom observation data to examine teachers’ and principals’ perspectives regarding their capacities to teach and manage large classes; what challenges large class sizes present; and what additional supports teachers and principals perceive to be necessary. Both teachers and principals reported that the current class size has a negative impact on teaching and learning. Additionally, both teachers and principals cited a need for more support in the form of (a) professional development; (b) workload reduction; and (c) increased resources. these areas of support could help to mediate the effects of large class size, including an almost sole reliance on lecturing with little teacher-to-student and student-to-student interaction.

INtRODUctION

The reality that teachers in developing countries teach large, and even overcrowded, classes is daunting and one that may not go away any time soon. The resolution arising from the 1990 Jomtien World Conference on Education for All, and the follow up later at the 2000 Dakar World Education Forum, has placed a very high emphasis on the need to expand access to education for all children. This goal, followed by high population growth has led to one positive, but also complex outcome – soaring enrolments, which in most cases are not accommodated by the recruitment of additional qualified teachers, the increase of physical space, and the provision of more textbooks and other teaching equipment. Sub-Sahara Africa is home to some of the largest classes where pupil-to-teacher ratios (PTR) are 70:1 in countries such as Congo, Ethiopia and Malawi, while South and East Asia follow closely with Afghanistan and Cambodia holding ratios of 55:1 or slightly higher (UNESCO 2006). According to the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO 2011, 2), data from 45 African countries shows that Sub-Sahara Africa has an average of 50 pupils per class, ‘a number that is much higher than average class sizes in the European Union or OECD member countries which are below 20 in the majority of classes and below 30 in all countries’. Although the concept of class size and how size impacts student performance has been and is still a matter of serious debate, research evidence is leading researchers to the conclusion that there are not two different strategies for teaching – one set of strategies for teaching small classes and a different set for teaching large classes. What really constitutes a large class is more a matter of context than a particular number of students or PTR.

Very large classes are the norm in many developing countries and are often perceived to be a threat to educational quality. In Kenya, we have seen that the introduction of the Free Primary Education (FPE) Policy in 2003 and the launching of the Free Secondary Education Programme in 2008 have more than doubled the number of pupils in both primary and secondary public schools. This problem has not only eroded teacher confidence, but has also placed the issue of class size at the forefront of the educational and political agenda in the country. As evidenced in numerous stories in the national newspapers, there has been an outcry from teachers and all citizens for the government to reduce class size by employing more teachers, and in recent times the shortage of teachers has led to union agitation against the government. Clearly, due to economic as well as political factors, the problem of large classes may not disappear from the Kenyan school system any time soon.

what challenges large class sizes present; and what additional supports teachers and principals perceive to be necessary.

cONtEXt

Argument for increasing teacher quality

Findings from current research on class size and its impact on student performance are increasingly leading to the dominant belief that merely reducing class size does not of itself guarantee positive student achievement. Rather than focus on the perceived benefits of small classes, attention is shifting to understanding teacher characteristics that foster positive change in students within large classes. Several studies have identified teacher quality as a key factor for successful learning in large classes (Benbow et al. 2007; Coleman 2011; Nakabugo et al. 2008; O’Sullivan 2006; Otienoh 2010; Wößmann and West 2006). Although it is logical to conclude that teaching practices shift when teachers move from a small class to a large class, research has consistently shown that teachers use the same strategies with small classes as they do with larger classes (Nakabugo et al. 2008) and that capable teachers are able to enhance the learning of their students no matter the class size (Wößmann and West 2006); it all rests on the quality of the teacher. This essentially means that a poor teacher would not be effective even with a small class. Coleman (2011) concludes that reducing PTR makes no difference based on a UNESCO report entitled ‘Financing the quality of education in Sub-Sahara Africa’. The report, published by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics in Montreal, was based on a thorough and comprehensive study carried out by the World Bank in Togo in 2003. It is evident, based on Coleman’s (2011) study and other studies on class size and student achievement, that class size on its own does not lead to any significant difference in learning outcomes, an observation that has invited focus on the need to study teacher roles in the context of large classes and approaches that are beneficial for teachers and students in large classes (Benbow et al. 2007; Nakabugo et al. 2008; O’Sullivan 2006; Otienoh 2010; Wößmann and West 2006). Coleman (2011) suggests that more investments should be focused on improving teacher quality instead of making any drastic attempts to reduce class size. Given that efforts in class size reduction could be hampered by economic and other factors, research in such contexts should address one critical question: How can teachers in developing countries be supported in coping with the pedagogical challenges of teaching large classes? The answer seems to lie in building teacher capacity in large class pedagogy (LCP). Buckingham (2003, 71) asserts the importance of quality teacher preparation by stating that,

class size has less effect when teachers are competent and the single most important influence on

student achievement is teacher quality. Research shows unequivocally that it is far more valuable

Thus, teachers need to be prepared with pedagogical skills to meet all of the challenges they will face, including large class size.

In order to enhance teaching and learning in large classes, there is a need for a paradigm shift. Benbow et al. (2007), Nakabugo et al. (2008), O’Sullivan (2006), and Wößmann and West (2006) have urged educators to move away from worrying about class reductions to focusing on the needs of teachers in large classes. Wößmann and West’s (2006) study, under the International Association for Evaluation and Educational Achievement (IEA) for the Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), reviewed class size effects in 18 different school systems around the world. By removing the bias often associated with conventional estimates of the effects of class size, the researchers found that out of the 18 countries in the study, small classes were beneficial in Greece and Iceland but were not at all beneficial in Japan and Singapore. In Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Korea, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia and Spain, the effects of class size on student performance were ruled out while the study did not document any conclusive evidence in class size and performance (Wößmann and West 2006). The authors noted that in countries where class size does not seem to have any effects on performance, teachers are highly qualified, which is true for Japan and Singapore (Wößmann and West 2006).

Although there have been efforts in different countries to introduce class size reduction policies, with specific reference to the United States (US) following the research findings from Project STAR, large class sizes are not likely to disappear in the near future (UNESCO 2006). For most developing countries in particular, reducing class sizes to numbers where a positive impact begins to be felt is not economically viable. In reference to research by the World Bank (2003) on the effects of class size in Togo, Coleman (2011) summarises the conclusions of that study as follows:

1. Most expensive innovation is increasing teacher qualifications to first degree. 2. Cheapest innovation is increasing the number of textbooks.

3. Biggest impact on scores comes from increasing teachers’ qualifications to secondary school certificate.

4. Least impact on scores (zero) comes from decreasing class size.

5. Most cost effective innovation per dollar is increasing the number of textbooks. 6. Least cost effective innovation (zero) is decreasing class size.

In his Ugandan example, the following strategies were observed among effective teachers: teachers praised the children; asked lots of questions; explained clearly; used eye contact; scanned the classroom constantly; used repetition when necessary; used detailed lesson plans; and were animated and enthusiastic. Therefore, the current study was motivated by the need to understand how graduate secondary school teachers perceive their capacity to handle large classes, as well as obtain their principals’ perspectives on this issue.

lItERAtURE REVIEW

large class pedagogy

There are various problems associated with large classes that affect both teachers and students. According to Benbow et al. (2007), large classes in developing countries adversely impact two significant and interrelated aspects of a teacher’s practice, namely, instructional time and classroom management. These researchers have observed that the teaching of mathematics, reading and writing suffer the most due to time constraints and that balancing time between instructional activities and classroom management is a serious challenge for many teachers. There are also effects on teacher motivation and classroom motivation, which in turn affects student engagement. Students in large classes suffer academically in that it is more difficult for teachers to evaluate and meet the needs of individual students.

Teachers who are faced with overcrowded or large class sizes face obstacles in the quality of education being delivered (Benbow et al. 2007). Most teachers feel that it is easier to teach smaller classes and some researchers propose that smaller classes result in increased student performance because teachers are able to give individual students more attention, which is related to better morale among teachers (Anderson 2000; Rice 1999). Anderson (2000) also reports that in small classes there is greater knowledge of students and in-depth coverage of content. Knowing students is important in teaching and learning. Teachers with smaller classes give more individual attention to students, interact more with students, and use small groups more frequently than teachers with large classes (Rice 1999). Blatchford, Bassett and Brown (2011) examined the effect of class size on teacher-to-student interactions and noted a tendency for students in large classes to drift off task due to lack of individualised attention. In spite of the general view that large classes are problematic, Blatchford (2003) has argued that large classes also provide opportunities that may not be available in small classes. For example, in large classes, teacher-to-student interactions may decrease, but students may interact more with their peers, meaning that large classes present not just difficulties but also opportunities for both teachers and students.

achievement at all levels of the education system (Blatchford et al. 2011; Carbone and Greenberg 1998; Cuseo 2007). Notably, large class size reduces active engagement by students in the learning process; decreases retention rates; lowers the frequency and quality of teacher-to-student interactions; while at the same time affecting how teachers give and obtain feedback from students (Blatchford et al. 2011; Cuseo 2007). Students in large classes have reported reduced motivation for learning and may not benefit from the development of the same level of cognitive skills as students in smaller classes (Carbone and Greenberg 1998; Cuseo 2007; Fischer and Grant 1983). Judging teacher quality based on students’ perceptions has shown that the quality of a teacher tends to decrease substantially with large class sizes (Bedard and Kuhn 2008). Effectiveness in teachers’ use of instructional resources is often affected by large class size to such an extent that the lecture method becomes the primary option and hence the dominant mode of instruction in large classes (Cooper and Robinson 1998).

What constitutes a large class is a matter of a person’s perspective, culturally, economically and politically. There have been differences documented on student, teacher and also societal perceptions of what may be termed as a large class. In the US, there have been notions of congestion, yet the average class size in a typical lower secondary school classroom is 24:1 (Rampell 2009). In China, a large English class is one that has 50–100 students, what most foreigners would describe as very large (Coleman 1989). In Kenya, the average class size is 45 according to the Institute for Public Policy and Research (Coleman 1989). Benbow et al. (2007, 2) report that, ‘overcrowded or large classrooms are those where the PTR exceeds 40:1. Such classroom conditions are particularly acute in the developing world where class size often swells up to and beyond 100 students’. However, O’Sullivan (2006) disagrees by stating that PTRs do not provide an accurate reflection of class size.

argue that class size effect depends on the specific school system, since schools differ in examination style; the existence of high stakes for students and teachers; remedial instruction for lagging students or enrichment programmes for outstanding students; the allocation of resources; teacher quality; and average class size.

Although class size reductions are often proposed as a way to improve student learning, research does not suggest that smaller classes will necessarily lead to improved student achievement (Hattie 2005; O’Sullivan 2006). It has been observed that even small classes can be seriously affected by inadequate teacher education as well as a lack of teacher experience. Lowering the number of students in a class does not guarantee quality of instruction; neither does increasing class size necessarily imply poor education (Maged 1997; Nakabugo et al. 2008). Ehrenberg et al. (2001) stress that class size reduction leads to improved student achievement only if teachers modify their instructional practices to take advantage of small classes.

Pre-service and in-service preparation

Any fruitful discussion of class size issues needs to take into account how teachers are being prepared to manage large classes by their pre-service programmes, as well as how they are supported at the in-service level. Even though changes have been made in the Kenyan schooling system, the teacher-training curriculum has not been modified (Otienoh 2010). Otienoh (2010) further suggests that teacher preparation programmes have failed to prepare future teachers to handle large classes. Benbow et al. (2007) point to a gap in preparation of teachers for large classes and observe that even though different methods are available for teachers, such as small groups, peer tutoring, shift teaching, team teaching, and lecturing depending on goals, there is a tendency for teachers to feel that teaching practices for overcrowded classes are limited. They argue that most teacher education coursework in developing countries does not seem to address the topic of teaching large classes; hence, ‘teachers are left unprepared for the unique challenges faced in the large classroom’ (Benbow et al. 2007, 8). The Kenya Ministry of Education (MoE 2004 in Otienoh 2010, 59) has accepted this responsibility, stating, ‘The MoE has not put in place a comprehensive teacher training curriculum to prepare teachers to cope with the changes and emerging challenges in teaching’. The MoE goes on to suggest that teacher preparation time is not enough; the several years of pre-service training does not prepare students for the rapid changes in social-economic changes (Otienoh 2010).

Garret and Bowles (1997 in Otienoh 2010, 57) express the need for training in context, ‘Effective teacher development cannot take place alienated from the context of practice’. Otienoh (2010) and Robinson (1990) also reiterate this point, stating that such support should be contextualised since class size effects vary depending on grade level, student characteristics, nature of the programme, teaching approach, and other interventions. Otienoh (2010) expresses the need for teachers to work with administrators to make decisions about the professional support they receive because the top-down approach seems not to work since teachers lack a sense of obligation when told what to do.

Bain, Lintz and Word (1989 in Underwood and Lumsden 1994, 5) researched the professional as well as the personal characteristics of 50 teachers who participated in Project STAR. The 50 teachers were selected for what was evaluated as exemplary teaching that resulted in students’ above average gains in reading and mathematics, within the state of Tennessee, US. These teachers were reported to have the following professional characteristics:

• high expectations of student learning; • clear, focused instruction;

• close monitoring of student learning and progress; • use of alternative methods when students did not learn; • use of incentives and rewards when students did not learn; • efficiency in their classroom routines;

• high standards of classroom behaviour; and • excellent personal interactions with students.

Through professional development, these American teachers were able to gain the needed experiences to advance their students intellectually.

‘teachers had to make the sudden shift without any prior arrangement for professional support to ease the transition’. We can infer that secondary school teachers were faced with similar demands with the introduction of Free Secondary Education (FSE) and hence they require focused and also contextualised support in large class pedagogy during pre-service preparation and in-service trainings.

RESEARcH QUEStIONS AND MEtHODS

In this research study, we used questionnaire, interview and classroom observation data to address the following research questions:

1. What are the sizes of secondary school classes in Kenya?

2. What are teachers’ perspectives regarding the effect of class size on teaching and learning?

3. What are principals’ perspectives on the effect of class size on teaching and learning? 4. What are teachers’ practices in teaching large classes?

We analysed these data in light of research literature in this area, while being open to other factors and patterns emerging within the context in which we were investigating. We collected data through questionnaires, interviews and classroom observations (see the appendices for the questionnaire and classroom observation protocols). Here, we report on the findings from the data collected through (a) questionnaires completed by 194 teachers from among 19 subject areas; (b) interviews with 18 Kenyan public secondary school principals; and (c) classroom observations of 18 classroom lessons across seven subject areas in Kenya public secondary schools.

Sample and data collection

In selecting schools and teachers, we began with the eight provincial regions of Kenya and selected at least one county from each of these regions, for a total of 12 counties. Kenya has 47 counties in all. Then we selected at least one school from each county with the overall criterion of having fairly equal representation from three types of schools – national schools (single gender, boarding school), county schools (single gender, boarding school), and district schools (most of which are mixed gender). We selected 18 schools across the 12 counties, with six national schools, six county schools, and six district schools. Thirty-eight per cent of the schools were boys’ schools, 36 per cent were girls’ schools, and 26 per cent were mixed gender schools, and were split almost equally between urban (56%) and rural (44%) schools.

total of 194 teachers who were teaching across 19 subjects. Forty-one per cent of the teachers who completed the questionnaire were females (n = 79) and 59 per cent were males (n = 115). The largest age group of teachers who completed the questionnaire were 30–39 years old (31.8%, n = 52), with the next largest group being 40–49 years old (27.1%, n = 52), followed closely by the group who were 25–29 years old (26.6%,

n = 51). More than half of the teachers who completed the questionnaire had taught for 10 years or less (31.3% had taught for less than five years; 21.4% had taught from five up to 10 years).

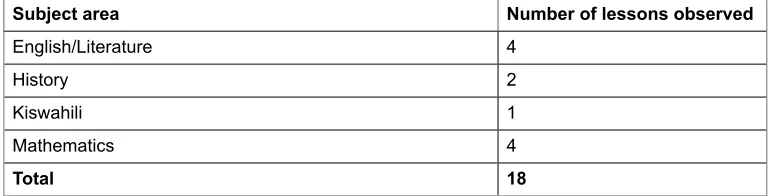

At each of the 18 schools, we interviewed the principal and observed a lesson. Female teachers taught 56 per cent of the lessons we observed (n = 10) and male teachers taught 44 per cent of the lessons we observed (n = 8). Table 1 shows the distribution of the counties and teachers who completed the questionnaire, while tables 2 and 3 show the distribution of the observed lessons across subject areas and grade levels.

Table 1: Distribution of counties and teachers who completed the questionnaire

Provincial region County Number of teachers

central (n = 29) Murang’a 29 coast (n = 19) Mombasa 19 Eastern (n = 26) Machakos 9

Makueni 17

Nairobi (n = 23) Nairobi 23 Northeastern (n = 25) Garissa 25 Nyanza (n = 24) Homa Bay 10

Nyamira 8

Kisii 6

Rift Valley (n = 26) trans Nzoia 26 Western (n = 22) Kakamega 15

Vihiga 7

Total 194

Table 2: Distribution of subject areas for observed lessons

Subject area Number of lessons observed

Biology 1

chemistry 3

Subject area Number of lessons observed

English/literature 4

History 2

Kiswahili 1

Mathematics 4

Total 18

Table 3: Distribution of grade levels for observed lessons

Grade level of students Number of lessons observed

Form I (first year of high school) 1 Form II (second year of high school) 9 Form III (third year of high school) 5 Form IV (fourth year of high school) 3

Total 18

Data analysis

We used an inductive approach to analyse the data by first compiling the data using SurveyMonkey (https://www.surveymonkey.com). We used data from the questionnaires and the observed lessons to answer the first research question: ‘What are the sizes of secondary school classes in Kenya?’ We used data from the questionnaires to answer the second research question: ‘What are teachers’ perspectives regarding the effect of class size on teaching and learning?’ We used data from the principal interviews to answer the third research question: ‘What are principals’ perspectives regarding the effect of class size on teaching and learning?’ We used data from the classroom observations to answer the fourth research question: ‘What are teachers’ practices in teaching large classes?’ We used open coding to establish codes for the data that appeared able to help answer the second and third research questions and then used axial coding to look for patterns and make sense of the data. Initially, we coded the data individually and then went over our codes to discuss any discrepancies and to resolve them so that we had shared understandings of the codes being used.

RESUltS

Sizes of Kenyan secondary school classes

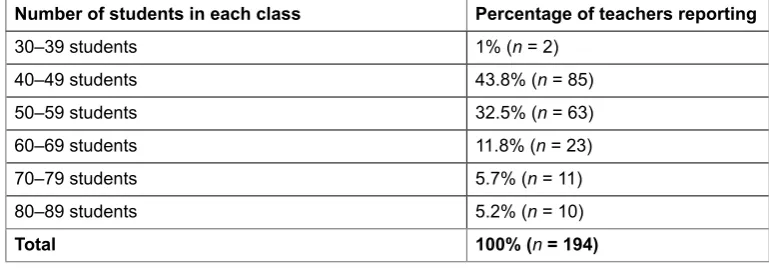

In analysing the data from the 194 teachers who completed a questionnaire and from the 18 observed lessons, we found a range of sizes of Kenyan secondary school classes. However, the vast majority of schools had between 40 and 59 students in each class. Researchers reported that 72.2 per cent of the 18 observed lessons (n = 13 lessons) had 40–59 students, while 76.3 per cent of the teachers (n = 148 teachers) who completed the questionnaire reported the number of students in each class at their schools being between 40 and 59 students. Table 4 shows the distribution of the number of students per class as reported by the teachers who completed the questionnaire, and Table 5 shows the distribution of the number of students in the lessons observed.

Table 4: Distribution of number of students in each class as reported by teachers

Number of students in each class Percentage of teachers reporting

30–39 students 1% (n = 2) 40–49 students 43.8% (n = 85) 50–59 students 32.5% (n = 63) 60–69 students 11.8% (n = 23) 70–79 students 5.7% (n = 11) 80–89 students 5.2% (n = 10)

Total 100% (n = 194)

Table 5: Distribution of number of students in observed lessons

Number of students in each class Number of lessons observed

40–49 students 7

50–59 students 6

60–69 students 4

70–79 students 1

Total 18

teachers’ perspectives on the effect of class size on teaching and

learning

The questionnaire responses from the teachers regarding the effect of class size on teaching and learning painted a picture of strong agreement on the negative effects of large classes (see Table 6).

Table 6: teachers’ perspectives on class size

Statement Percentage of teachers

teachers in my school have very large classes. 88.0% agree or strongly agree teaching large classes is not a problem in my school. 76.2% disagree or strongly disagree the school is adequately staffed with enough

graduate teachers. 71.9% disagree or strongly disagree classrooms in my school are too congested for

effective teaching. 58.3% agree or strongly agree

Ministry of Education officials play a very important

role in helping us become better teachers for large classes.

72.3% disagree or strongly disagree

Student performance in my school is not affected by

class size. 72.6% disagree or strongly disagree Performance in the subject I teach is negatively

affected by having large numbers of students. 68.1% agree or strongly agree teachers in my school are overworked. 70.8% agree or strongly agree

The vast majority of teachers (88%) agreed or strongly agreed that their schools have large classes. More than half of the teachers (58.3%) agreed or strongly agreed that classrooms in their schools are congested. More than two-thirds of the teachers (68.1%) agreed or strongly agreed that student performance in their classes is negatively affected by having a large number of students, and 70.8 per cent of the teachers agreed or strongly agreed that teachers in their schools are overworked.

There was clear support by more than 70 per cent of the teachers that teaching large classes is a problem in their schools (76.2%); the school is not adequately staffed with enough graduate teachers (71.9%); MoE officials do not play a very important role in helping them become better teachers for large classes (72.3%); and student performance is affected by class size (72.6%).

Table 7: Teachers’ confidence in handling large classes

Teaching task Percentage of teachers

Ability to identify learning needs of all my students 58.3% good or very good Ability to interact effectively with all my students 53.6% good or very good Ability to assist lagging students 56.5% fair or poor Ability to enrich well-performing students 69.8% good or very good Ability to manage my classroom 78.6% good or very good Ability to create warm and motivating learning atmosphere 75.3% good or very good Ability to create assessment modes that lead to meaningful

learning 66.3% good or very good

Ability to grade and provide quick feedback 61.3% good or very good Ability to support students with special needs in my classes 55.0% fair or poor

These tasks included identifying learning needs of all students (58.3%); interacting effectively with all students (53.6%); assisting lagging students (56.5%); enriching well-performing students (69.8%); providing quick feedback (61.3%); and supporting students with special needs (55%).

However, teachers were also able to identify a number of changes that could support more effective teaching (see Table 8).

Table 8: teachers’ perspectives on changes that could support more effective teaching

Category Number of teachers listing*

Professional development 41

Workload reduction

Employ more teachers 39

Reduce number of students per class 22 Reduce number of lessons per teacher 10 Integrate Ict into teaching and learning 8 Revise the syllabus to cover less material 4 Resources

Category Number of teachers listing*

Books, including textbooks 12 Excursions and practicals 8 Additional pay for teachers 6

More time for teaching 6

larger classrooms 5

Other

Parents provide textbooks 3 Parents pay school fees on time to avoid disruptions 1 Have an enrolment policy 1

*Some teachers listed more than one item

More than 20 per cent of the teachers (n = 41) listed a need for professional development, including teaching new pedagogical skills; a variety of ways of assessing student learning; ICT skills; team-teaching skills; and how to develop learner-centred materials. Many teachers (n = 83) commented on the need to reduce teachers’ workload, through employing more teachers; reducing the number of students per class; reducing the number of lessons per teacher; integrating ICT into teaching and learning; and revising the syllabus to cover less material. More than 60 per cent of the teachers (n = 117) noted the need for increased resources, including materials, facilities, equipment, books, excursions and practicals, additional pay, more time for teaching, and larger classrooms.

The teachers who completed the questionnaire were almost evenly split in viewing the role of their teacher training programme as supportive in preparing them for teaching large classes (48%) and as not helpful in this regard (52%). Many of those who saw their teacher training as helpful noted how the programme has helped them ‘handle my classes and to ensure I get the best out of each student’. Those who noted that their teacher training was not helpful in preparing them to teach large classes made comments that the training was not very effective ‘as it did not foresee the emerging issues in the education sector’, and ‘because they dwell on manageable numbers’.

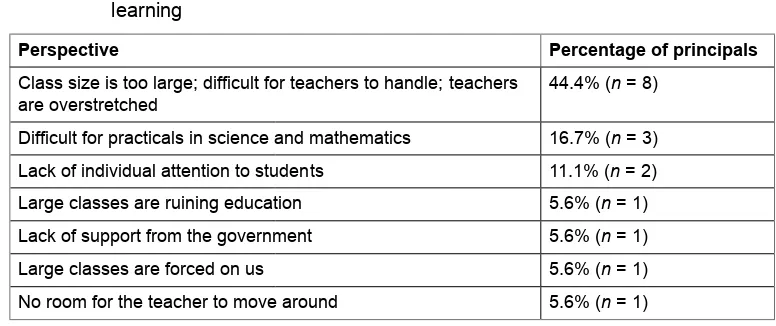

Principals’ perspectives on the effect of class size on teaching and

learning

Each of the 18 principals interviewed noted that class sizes in their school are too large. Two-thirds of the principals mentioned that the size is making the classes difficult to manage; two-thirds also noted that there is no end in sight to the issue – class size will continue to grow. The principals made remarks such as: ‘not healthy’; ‘overcrowded and inaccessible during teaching’; ‘teacher-to-student interaction is very low’; ‘little attention to individual differences’; and ‘a challenge to teachers, especially when managing slow learners who may not participate fully’.

The researchers asked the principals what they consider to be an ideal class size for their schools. Out of 18 responses, 14 fell in the range of 30–40 students per class, while four responses were in the 40–50 students range. Five principals gave an exact number of 35 students per class; one principal thought 30 students per class would be ideal; another thought 45 students would be ideal; and one thought 40 students would be the maximum number of students per class that would be manageable.

The principals who were interviewed had a range of perspectives on the effect of class size on teaching and learning, all of them negative. Table 9 lists these perspectives, which are in line with the teachers’ responses to the questionnaires.

Table 9: Principals’ perspectives on the effects of class size on teaching and learning

Perspective Percentage of principals

Class size is too large; difficult for teachers to handle; teachers

are overstretched 44.4% (n = 8)

Difficult for practicals in science and mathematics 16.7% (n = 3) lack of individual attention to students 11.1% (n = 2) large classes are ruining education 5.6% (n = 1) lack of support from the government 5.6% (n = 1) large classes are forced on us 5.6% (n = 1) No room for the teacher to move around 5.6% (n = 1)

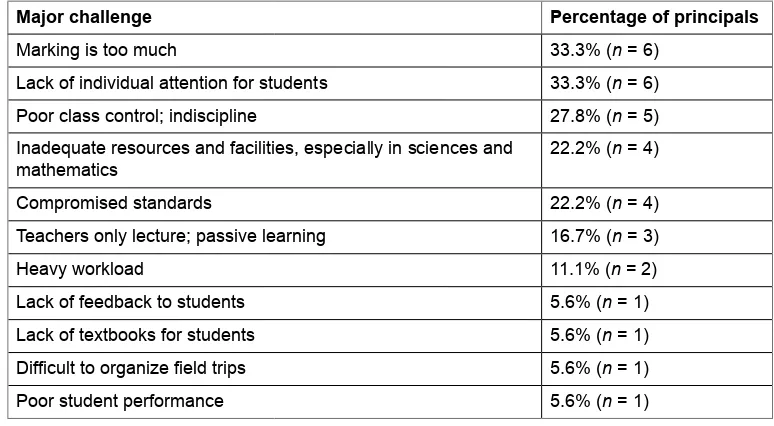

Researchers asked the principals their perspectives on the major challenges related to large class sizes and the principals’ responses demonstrated a concern for the teaching and learning occurring in their schools (see Table 10).

Table 10: Principals’ perspectives on the major challenges related to class size

Major challenge Percentage of principals

Marking is too much 33.3% (n = 6) lack of individual attention for students 33.3% (n = 6) Poor class control; indiscipline 27.8% (n = 5) Inadequate resources and facilities, especially in sciences and

mathematics 22.2% (n = 4)

compromised standards 22.2% (n = 4) teachers only lecture; passive learning 16.7% (n = 3)

Heavy workload 11.1% (n = 2)

lack of feedback to students 5.6% (n = 1) lack of textbooks for students 5.6% (n = 1)

Difficult to organize field trips 5.6% (n = 1) Poor student performance 5.6% (n = 1)

Almost all of the challenges noted can affect student learning. When asked how class size affects student performance in their schools, the principals noted the lack of individual attention (33.3%); poor class control (27.8%); inadequate resources and facilities (22.2%); and compromised standards (22.2%). All of the principals noted that they lacked resources; needed more teachers; had inadequate classroom space; a lack of textbooks and other books; inadequate laboratory equipment and materials; inadequate boarding facilities; and a lack of ICT equipment for teachers and students.

Out of the 18 principals, 12 noted that there is no support in the school or through the government to improve teachers’ skills in meeting the diverse needs of large classes. Six of the principals reported that there are workshops or seminars for teachers in their schools. Almost the same percentages of principals reported similar responses related to support for teachers who find it difficult to manage teaching large classes: 11 out of 18 principals said there is no support; six said that there are workshops or seminars for this purpose (with several providing lunch as motivation for teachers); and one noted that all the teachers at his/her school are competent.

and/or had students work in groups in class; and two mentioned that the teachers use ICT as a way of engaging students in learning more actively.

The principals overwhelmingly (77.8%) viewed pre-service teacher programmes as not preparing teachers with the attitudes and skills necessary to teach large classes, with another principal noting that he/she did not know. Three principals thought that pre-service teacher programmes were preparing the teachers adequately with regard to teaching large classes. One principal noted the need for pre-service teacher programmes to include this in their programmes ‘now that the problem is with us’. The vast majority of the principals (72.2%) see teaching experience as important in teachers being able to handle large classes. Their comments indicated that experienced teachers ‘have devised their own ways that work’; ‘can handle classes differently depending on the students’ level’; and ‘learn to diversify teaching and methods and become more innovative with time’.

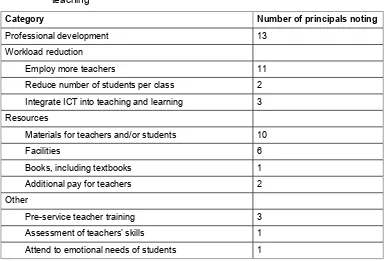

We found that the principals’ perspectives on changes that could support more effective teaching coincided in many ways with the teachers’ perspectives (see Table 11).

Table 11: Principals’ perspectives on changes that could support more effective teaching

Category Number of principals noting

Professional development 13 Workload reduction

Employ more teachers 11

Reduce number of students per class 2 Integrate Ict into teaching and learning 3 Resources

Materials for teachers and/or students 10

Facilities 6

Books, including textbooks 1 Additional pay for teachers 2 Other

Pre-service teacher training 3 Assessment of teachers’ skills 1 Attend to emotional needs of students 1

for example, by employing more teachers; reducing the number of students per class; or integrating ICT into teaching and learning. All of the principals identified additional resources as being necessary to have more effective teaching with large classes, including materials for teachers and students, facilities, books, and additional pay for teachers. Three principals spoke about the need for training pre-service teachers to teach large classes, while one spoke extensively about the need to attend to the students’ emotional needs.

teachers’ practices in teaching large classes

In the 18 classroom lessons that we observed, we found that the teachers spent the majority of the lesson time lecturing. As shown in Table 12, the teachers spent little lesson time on demonstration, class practicals, question and answer time, pair or group work, or class discussion.

Table 12: lesson time spent on different instructional methods

Instructional method Lesson time spent

lecture 58.8% of teachers spent 50–100% of lesson time Demonstration 100% of teachers spent 0–25% of lesson time class practical 100% of teachers spent 0–25% of lesson time Question and answer 66.7% of teachers spent 0–25% of lesson time Pair or group work 88.9% of teachers spent 0–25% of lesson time class discussion 88.9% of teachers spent 0–25% of lesson time

For half of the lessons (nine out of 18) we observed, the teachers had a lesson plan or lesson notes. In five of these cases, the lesson plan was drawn from a scheme of work (the plans for the entire term). Researchers noted that in 15 out of the 18 lessons, the classroom was congested, and noted that while in some cases the classrooms were large enough to accommodate the number of students, in other cases there was no space between the desks and the students were too close to the blackboard and to the teacher. One researcher noted that there was no room for the teacher to manoeuvre in the classroom so the teacher stayed at the front. Another researcher noted the same situation and commented, ‘The classroom did not allow the teacher to reach all learners effectively. The teacher stood in front of the classroom throughout the lesson.’ For another lesson, the researcher noted that the students were sharing desks and participation was very limited. Another researcher noted that the students ‘had to write on their laps’.

of the lessons (9 out of 18) researchers noted that the textbooks were adequate; for the other half of the lessons, the researchers noted that students had to share textbooks.

Researchers rated the teacher-to-student interaction as ‘good’ in two of the lessons; as ‘fair’ in six of the lessons; and as ‘poor’ in 10 of the lessons. Researcher comments included: ‘There was minimal interaction due to space. The large numbers of students hindered movement of the teacher to maintain the attention of all students’; and ‘She tries to reach all students, but only a few can get turns to read and contribute’. These ratings and comments demonstrate the constraining effect of a large number of students on teacher-to-student interaction. Large class size may also have contributed to the minimal student-to-student interaction noted by the researchers. In 15 of the 18 observed lessons, researchers noted that there was no student-to-student interaction or very minimal, if any. Researchers further noted that for two of the lessons, student-to-student interaction was good, while for another lesson the researcher commented that student-to-student interaction was ‘fairly good given the prevailing circumstances; only limited due to facilities and time’.

Despite the large class size, researchers noted that the teacher was able to manage classroom activities effectively within the time and space available in 12 out of the 18 lessons, and in 16 of the 18 observed lessons researchers noted that the teacher had good control of the class. Researchers also noted in 14 out of the 18 lessons that the lesson objectives had been achieved, and that in all 18 lessons the teachers were generally confident.

cONclUSION

Class size in Kenyan public secondary schools is generally 40–59 students per class, which the participants (teachers and principals) agreed is too large. The research literature would also classify this as a large class (Benbow et al. 2007). Both teachers and principals reported that the current class size has a negative impact on teaching and learning due to a heavy workload for the teachers in terms of marking; a lack of individual attention for the students; inadequate resources such as textbooks; and the teachers feeling limited to using mainly lecture as an instructional approach.

Approximately two-thirds of the principals reported that there is no support at the school or MoE level for preparing the teachers in large class pedagogy. Most also did not see the pre-service teacher programmes preparing teachers with these skills. Further research is needed to determine what type of professional development and pre-service teacher education would be most helpful and most effective in preparing the teachers in large class pedagogy.

and (c) increased resources (e.g. materials for teaching and learning, books, facilities, equipment). These areas of support could help to mediate the effects of large class size that researchers observed in the lessons, which included an almost sole reliance on lecturing with little teacher-to-student and student-to-student interaction.

The Kenyan government’s role in assisting schools to realise the goals of quality education is evident through efforts to increase the number of teachers in order to cope with the increased enrolment brought about by the FPE Policy (Abuya et al. 2015). In spite of this, Kenyan schools continue to grapple with the problem of teacher shortage (Majanga, Nasongo and Sylvia 2011). Additionally, a lack of resources, especially printed materials and textbooks. has affected instruction in large classes, as well as a lack of trained teachers (Oketch et al. 2010).

The implementation process for FPE, which was to ensure that the massive enrolment in Kenyan schools was effectively managed failed as a result of weak implementation policies that relied mainly on top-down instead of bottom-up approaches or a combination of both (Abuya et al. 2015). Bottom-up approaches encourage team work, focused leadership and excellent communication, whereas top-down approaches hinder the translation of policy into practice.

Although ICTs have been reported to play a key role in managing large classes, and in improving learning outcomes, many developing countries, including Kenya, have not utilised technology in classrooms as might have been expected (Kisirkoi 2015; Kombo 2015). This difficulty has been noted in Kenya in spite of the government’s demonstrated effort to support the use of ICT in teaching and learning (Kombo 2015). In making recommendations that could see improved ICT use in Kenyan schools, Kisirkoi (2015) advises that the teachers be encouraged to take the initiative, with the school leadership supporting them, to create an enabling environment for ICT use. Her case study of one school that had successfully integrated ICT into teaching and learning in a Kenyan secondary school found that school leadership is a key factor in its successful implementation. The Kenyan government can promote ICT use by encouraging the formulation and implementation of school-based policies.

It is clear that the demand for secondary school education in Kenya, and in many developing countries, will continue to grow. While the need for hiring more graduate teachers is high, equally important is the need for training all teachers, pre-service and in-service, in large class pedagogy, the use of ICT and other tools to support teaching and learning, and providing sufficient resources for teachers to be able to support students in learning. Dealing with these needs appears to be critical in helping teachers cope with the difficulties associated with teaching large classes.

AcKNOWlEDGEMENtS

Education for Development (HED) office, as well as by the Schools of Education at Kenyatta University and Syracuse University. The contents are the responsibility of the researchers from Kenyatta University and Syracuse University and do not necessarily reflect the views of HED, USAID or the United States Government.

REFERENcES

Abuya, B. A., K. Admassu, M. Ngware, E. Onsomu and M. Oketch. 2015. Free primary education and implementation in Kenya: The role of primary school teachers in addressing the Policy Gap. SAGE Open January–March: 1–10. DOI: 10.1177/2158244015571488

Anderson, L. W. 2000. Why should reduced class size lead to increased student achievement? In How small classes help teachers do their best, ed. M. C. Wang and J. D. Finn, 3–24. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Center for Research in Human Development and Education.

Bedard, K. and P. Kuhn. 2008. Where class size really matters: Class size and student ratings of instructor effectiveness. Economics of Education Review 27(3): 253–265.

Benbow, J., A. Mizrachi, D. Oliver and L. Said-Moshiro. 2007. Large classes in the developing world: What do we know and what can we do? New York: American Institute for Research under the EQUIP1 LWA.

Blatchford, P. 2003. A systematic observational study of teachers’ and pupils’ behavior in large and small classes. Learning and Instruction 13(6): 569–595.

Blatchford, P., P. Bassett and P. Brown. 2011. Examining the effect of class size on classroom engagement and teacher-pupil interaction: Differences in relation to pupil prior attainment and primary vs. secondary schools. Learning and Instruction 21: 715–730.

Buckingham, J. 2003. Class size and teacher quality. Educational Research for Policy and Practice 2(1): 71–86.

Carbone, E. and J. Greenberg. 1998. Teaching large classes: Unpacking the problem and responding creatively. In To improve the academy, ed. M. Kaplan, Vol. 17, 311–326. Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press and Professional and Organizational Development Network in Higher Education.

Coleman, H. 1989. How large are large classes? Lancaster-Leeds Language Learning in Large Classes Research Project Report 4: 1–59.

Coleman, H. 2011. Reducing teacher-pupil ratio makes no difference. http://telcnet.weebly.com/1/ post/2011/08/first-post.html (accessed June 25, 2014).

Cooper, J. and P. Robinson. 1998. Small-group instruction in Science, Mathematics, Engineering and Technology (SMET) disciplines: A status report and an agenda for the future. Journal of College Science Teaching 27(6): 383–388.

Ehrenberg, R., D. Brewer, A. Gamoran and J. Willms. 2001. The class size controversy. CHERI Working Paper #14. http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/working/papers/25/ (accessed June 25, 2014).

Fischer, C. and G. Grant. 1983. Intellectual levels in college classrooms. In Studies of college teaching: Experimental results, ed. C. L. Ellner and C. P. Barnes. Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath.

Harfitt, G. 2012. An examination of teachers’ perceptions and practice when teaching large and reduced size classes: Do teachers really teach them in the same way? Teaching and Teacher Education 28(1): 132–140.

Hattie, J. 2005. The paradox of reducing class size and improving learning outcomes. International Journal of Educational Research 43(6): 387–425.

Hayes, U. 1997. Helping teachers to cope with large classes. ELT Journal 51(2): 106–116.

Kisirkoi, F. K. 2015. Integration of ICT in education in a secondary school in Kenya: A case study. Literacy, Information and Computer Education Journal 6(2): 1345–1350.

Kombo, N. 2013. Enhancing Kenyan students’ learning through ICT tools for teachers. Centre for Educational Innovation: An initiative of Results for Development Institute. http://www.educationinnovations. org/blog/enhancing-kenyan-students-learning-through-ict-tools-teachers

Maged, S. 2007. The pedagogy of large classes: Challenging the ‘Large classes equals gutter education myth’. Doctoral dissertation, University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

Majanga, E. K., J. W. Nasongo and V. K. Sylvia. 2011. The effect of class size on classroom interaction during mathematics discourse in the wake of free primary education: A study of public primary schools in Nakuru Municipality. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences 3(1): 44–49.

Nakabugo, M., C. Opolot-Okurut, C. Ssebbunga, J. Maoni and A. Byamugisha. 2008. Large class teaching in resource constrained context: Lessons from reflective research in Ugandan primary schools.

Journal of International Cooperation in Education 11(30): 85–102.

Oketch, M., M. Mutisya, M. Ngware and A. C. Ezeh. 2010. Why are there proportionately more poor pupils enrolled in non-state schools in urban Kenya in spite of FPE policy? International Journal of Educational Development 30(1): 23–32.

O’Sullivan, M. 2006. Teaching large classes: The international evidence and a discussion of some good practice in Ugandan primary schools. International Journal of Educational Development 26(1): 24– 37.

Otienoh, R. 2010. The issue of large classes in Kenya: The need for professional support for primary school teachers in school contexts. International Studies in Educational Administration 38(2): 57–72.

Rampell, C. 2009. Class size around the world. www.economix.blogs.nytimes.com (accessed June 25, 2014).

Rice, J. 1999. The impact of class size on instructional strategies and the use of time in high school mathematics and science courses. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 21(2): 215–229.

Underwood, S. and L. Lumsden. 1994. Class size. Research Roundup: National Association of Elementary School Principals 11(1): 2–5.

United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). 2006. Comparing education statistics across the world. Global Education Digest. Montreal: UNESCO Institute of Statistics.

United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). 2011. School and teaching resources in sub-Sahara Africa: Analysis of the 2011 UIS Regional Data on Education. UIS Information Bulletin No. 6. Montreal: UNESCO Institute of Statistics.

Ur, P. 1996. A course in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

APPENDIcES

APPENDIX 1: teacher Questionnaire on large classes

This questionnaire has been prepared by both Kenyatta University and Syracuse University in collaboration with the Ministry of Education. Its major purpose is to collect information about issues, challenges, teaching and management of large classes in Kenyan secondary schools. The information you provide will be used to help improve the teacher-training programme at our local universities.

A. PERSONAl INFORMAtION tick one space as appropriate

1. Gender: □ Male □ Female

2. Age: □ less than 24 □ 25–29 □ 30–39 □ 40–49 □ 50–59

3. Teaching experience: □ Less than 5 years □ 5–10 □ 10–15 □ 15–20 □ 20 and above

4. Subjects taught: 1 ___________________________

2 ___________________________

B. ScHOOl INFORMAtION 1. □ Girls □ Boys □ Mixed 2. □ Rural □Urban

3. county ___________________________________________ 4. Average number of students per class ___________________

c. tEAcHER VIEWS

Please indicate whether you agree or disagree with statements below by placing a tick in the appropriate space.

Strongly Agree (SA), Agree (A), Disagree (D), Strongly Disagree (SD), Not Sure (NS) 1. teachers in my school have very large classes.

□ SA □ A □ D □ SD □ NS

2. Teachers in my school are confident in handling large classes. □ SA □ A □ D □ SD □ NS

3. teaching large classes is not a problem in my school. □ SA □ A □ D □ SD □ NS

4. the school has enough resources and facilities to support teaching and learning. □ SA □ A □ D □ SD □ NS

5. the school is adequately staffed with enough graduate teachers. □ SA □ A □ D □ SD □ NS

7. the school administration provides teachers with support for teaching large classes. □ SA □ A □ D □ SD □ NS

8. Ministry of Education officials play a very important role in helping us become better teachers for large classes.

□ SA □ A □ D □ SD □ NS

9. Student performance in my school is not affected by class size. □ SA □ A □ D □ SD □ NS

10. Performance in the subject l teach is negatively affected by having large number of students.

□ SA □ A □ D □ SD □ NS

11. teachers are able to cover syllabus using regular regular class lessons. □ SA □ A □ D □ SD □ NS

12. teachers in my school are overworked. □ SA □ A □ D □ SD □ NS

13. teachers in my school are motivated to do their work. □ SA □ A □ D □ SD □ NS

D. tEAcHER SKIllS IN HANDlING lARGE clASSES

Please rate your level of confidence and your skills in handling large classes. Tick as appropriate.

Very good (VG), Good (G), Fair (F), Poor (P)

1. Ability to identify learning needs of all my students. □ VG □ G □ F □ P

2. Ability to interact effectively with all my students. □ VG □ G □ F □ P

3. Ability to assist lagging students. □ VG □ G □ F □ P

4. Ability to enrich well performing students. □ VG □ G □ F □ P

5. Ability to manage my classroom. □ VG □ G □ F □ P

6. Ability to create warm and motivating learning atmosphere. □ VG □ G □ F □ P

7. Ability to create assessment modes that lead to meaningful learning. □ VG □ G □ F □ P

8. Ability to grade and provide quick feedback. □ VG □ G □ F □ P

9. Ability to use different student activities. □ VG □ G □ F □ P

10. Ability to use the lecture method effectively. □ VG □ G □ F □ P

12. Ability to use computers. □ VG □ G □ F □ P

13. Ability to create your own teaching materials. □ VG □ G □ F □ P

14. Ability to creatively use other methods apart from lecturing. □ VG □ G □ F □ P

15. Ability to support students with special needs in my classes. □ VG □ G □ F □ P

E. SUPPORt WItH tEAcHING OF lARGE clASSES

1. Would you like any kind of assistance in order to teach your class more effectively?

□ Yes □ No

2. If your answer is yes, what kind of assistance or skills would you need? _______________________________________________________________ 3. How would you describe the role played by your teacher training programme in

making you better able to teach large classes?

_______________________________________________________________ 4. Identify any specific support that your school administration and the Ministry of

Education have provided to support you in teaching large classes.

_______________________________________________________________ 5. What additional information or comments would you like to share with us

regarding teaching of large classes in your specific school?

APPENDIX 2: classroom Observation Guide

this instrument was prepared by both Kenyatta University and Syracuse University in collaboration with the Ministry of Education. Its purpose is to collect information in Kenyan secondary schools regarding issues, challenges as well as strategies relating to large classes in Kenya.

1. Date: ________________________ 2. class level: ___________________ 3. Subject: ______________________ 4. School category :_______________ 5. No of students in class: __________

6. a) What percentage of lesson time is used by teacher based on following instructional methods?

Lecture □ 100%, □ 75%, □ 50%, □ 25%, □ 0% Demonstration □ 100%, □ 75%, □ 50%, □ 25%, □ 0% Class practical □ 100%, □ 75%, □ 50%, □ 25%, □ 0% Question/Answer □ 100%, □ 75%, □ 50%, □ 25%, □ 0% Pair and group work □ 100%, □ 75%, □ 50%, □ 25%, □ 0% Class discussion □ 100%, □ 75%, □ 50%, □ 25%, □ 0% Other (specify) ___________________________________________ 6. b) Does the teacher have a lesson plan or lesson notes? □ Yes □ No 6. c) Is lesson drawn from a scheme of work? □ Yes □ No 7. Is classroom too congested? □ Yes □ No Explain ____________________________________________________ 8. Has teacher used special classroom arrangement in order to adequately to

address today’s lesson objectives? □ Yes □ No Explain ____________________________________________________

9. Describe nature of teacher student interaction and effects of large class size if any. __________________________________________________________

10. Describe nature of student to student interactions.

__________________________________________________________ 11. Describe availability of resources, desks, books, etc.

__________________________________________________________ 12. Is teacher able to manage classroom activities effectively within time and space

available? □ Yes □ No

APPENDIX 3: Principal Interview Protocol

this protocol was prepared by both Kenyatta University and Syracuse University in collaboration with the Ministry of Education. Its purpose is to collect information in Kenyan secondary schools regarding issues, challenges as well as strategies relating to large classes in Kenya.

1. What do you think about the size of secondary school classrooms in Kenya? __________________________________________________________

2. What do you consider to be the ideal class size in your school or education zone? __________________________________________________________

3. What are your views about class size in your specific school?

__________________________________________________________ 4. What do teachers in your school feel about class size?

__________________________________________________________ 5. What major issues relate to class size in your school?

__________________________________________________________ 6. How do you think class size affects student performance in your school? __________________________________________________________

7. Do you feel that you have adequate resources for the number of students in your school, such as teachers, classrooms, print and other materials?

__________________________________________________________ 8. Do you think that teachers in your school are skilled enough to meet diverse

needs of large classes?

__________________________________________________________

9. Is any specific support provided for teachers that are not able to manage teaching effectively due to large classes?

__________________________________________________________

10. Do you think teachers in your school use any specific strategies to meet the needs of large classes?

__________________________________________________________ 11. Do you think preservice training in Kenya prepares graduate teachers with

attitudes and skills necessary for teaching large classes?

__________________________________________________________

12. Is the length of teaching experience important in handling a large class? Explain. __________________________________________________________