THE UTILISATION AND CONSERVATION OF INDIGENOUS

MEDICINAL PLANTS IN SELECTED AREAS IN BARINGO

COUNTY, KENYA

By

CAROL JERUTO ROTICH (B.ENV S. ERC)

A Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment for the Award of Degree of Master of Environmental Science of Kenyatta University, Nairobi.

DECLARATION

This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for a degree or award in

any other University.

CAROL JERUTO ROTICH Date

Reg. No: N50/CTY/PT/23013/2011

Declaration by Supervisors

We confirm that the work reported in this thesis was carried out by the candidate

under our supervision as the University Supervisors.

Dr. Najma Dharani Date

Department of Environmental Sciences Kenyatta University

Kenya.

Dr. Esther Kitur Date Department of Environmental Sciences

DEDICATION

I dedicate this work to my husband Hillary and sons Leroy, Lerin and Leron for

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Foremost, I would like to express my deepest thanks to my two supervisors, Dr.

Najma Dharani and Dr. Esther Lesan Kitur. Their patience, encouragement, and

immense knowledge were key motivations throughout my Master Programme.

They carried out their supervision with an objective and principled approach to

Environmental Science. They persuasively conveyed an interest in my work.

Dr. Dharani has been my supervisor and guiding beacon from proposal

development to report writing. I am truly thankful for her steadfast integrity and selfless dedication to my academic development. Dr. Kitur is a mentor from whom

I have learnt the vital skill of disciplined critical thinking in the field of research

and environment. Her supervision, guidance and scrutiny of my proposal and

thesis writing have been invaluable. She has always found the time to propose

consistent excellent improvements. I owe a great debt of gratitude to Dr. Dharani

and Dr. Kitur.

Special thanks to Mr. Demissew for his assistance and guidance in data analysis

and report writing.

To my parents Mr&Mrs Rotich, thank you for everything; Moral, financial and spiritual support. You made me into who I am today! I thank my parents‟ in-law

Mr&Mrs Kwambai for their constant support and invaluable encouragement to

Idah, Ruth & Tito and in-laws Viola, Kathurima, Lyce & Becky; I am grateful for

their encouragement, prayers and constant reminder that I had to complete my

work as soon as possible.

To Mr. Paul Maiyo and his family, I am grateful for your support and treating me

as one of your children all times.

To my friends Ndeda, Mirriam, Jela, Kiptore and Faith I say thank you for your

continued friendship, support, encouragements and prayers. To my classmates

Linet, James, Nkatha, Eric-Moses, Kipchumba, Mbugua, Philip, Aura, Shikorire,

David and Wadegu, thank you all for the helpful discussions and for providing

enlightenment and encouragement every now and then.

Finally, I would like to thank my sons-Leroy, Lerin & Leron and husband Hillary

for their love and constant support, for all the late nights and early mornings, and

for keeping me sane when I thought I could not go on with this thesis. Hillary,

thank -you for being my editor, proof-reader and sounding board. But most of all,

thank you for being my best friend. I owe you everything.

Above all, I thank the Almighty God for constantly renewing my strength and

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DECLARATION ...ii

DEDICATION ... iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ... iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... vi

LIST OF TABLES ... ix

LIST OF FIGURES ... x

LIST OF PLATES ... xi

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ...xii

ABSTRACT ... xiii

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1 Background to the Problem ... 1

1.2. Statement of the Problem and Justification of the Study ... 3

1.3. Research questions ... 5

1.4. Research Hypotheses ... 5

1.5. Broad objective ... 6

1.5.1. The Specific objectives ... 6

1.6. Significance of the study ... 6

1.7. Conceptual framework ... 7

1.8. Definition of operational terms ... 9

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW ... 12

2.1. Overview of traditional Medicinal Plants ... 12

2.2. Arid and Semi-Arid Lands and Indigenous Medicinal Plants ... 15

2.3. Threats to Traditional Medicinal Plants ... 17

2.3.1. Deforestation ... 19

2.3.2. Human density and biodiversity risk ... 21

2.3.3. Land tenure policies ... 21

2.3.4. Erratic Rainfall and Droughts ... 22

2.3.5. Impact of livestock grazing ... 22

2.4. Health seeking and use of herbal medicines ... 23

2.5. Use of indigenous medicinal plants in various communities in Kenya ... 24

2.6. Composition of medicinal plants ... 24

2.7. Abundance of Medicinal plants ... 25

2.8. Medicinal plants diversity and conservation ... 25

2.9. Utilization of IMPs ... 26

CHAPTER 3: METHODOLOGY ... 28

3.1. Introduction ... 28

3.2. Study area ... 28

3.2.1. Study area location ... 28

3.2.2. Climate and Relief ... 28

3.2.3. Vegetation ... 30

3.2.6. Population of the Study area ... 31

3.3. Research design ... 31

3.3.1. Selection of the Study Area ... 31

3.4. Sampling procedure ... 32

3.5. Data collection ... 32

3.5.1 Administration of questionnaires ... 32

3.5.2 Transects ... 33

3.6. Data analysis and presentation ... 34

CHAPTER 4: RESULTS AND DISCUSIONS ... 35

4.1. Introduction ... 35

4.2. Respondents profile and background ... 35

4.2.1. Gender of the respondents ... 35

4.2.2. Household head ... 35

4.2.3. Ages of the respondents ... 36

4.2.4. Education Level ... 37

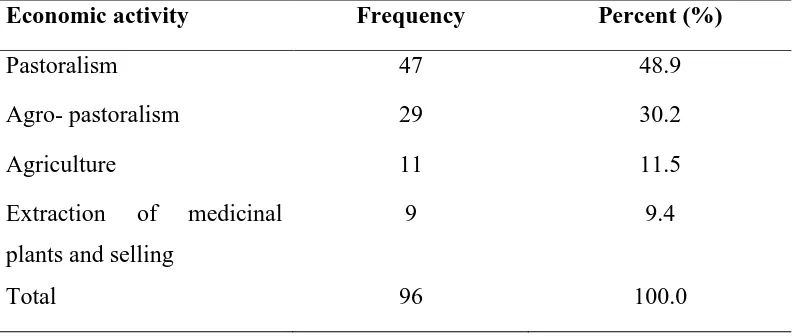

4.2.5. Household Economic Activity ... 38

4.2.6. Preferred means of treatment ... 39

4.3. Composition and abundance of the common Indigenous Medicinal Plants (IMPs) in Koipiriri, Ikumae and Ilchurai ... 40

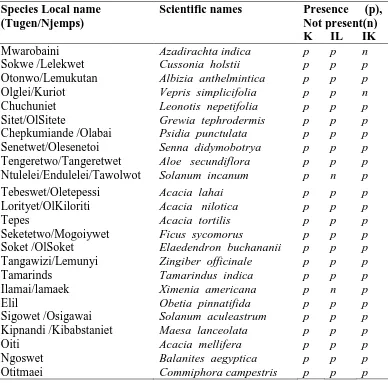

4.3.1. Composition of the Common IMPs in the study areas ... 40

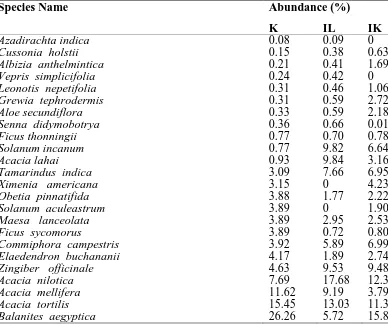

4.3.2. Abundance of IMPs in the study sites ... 41

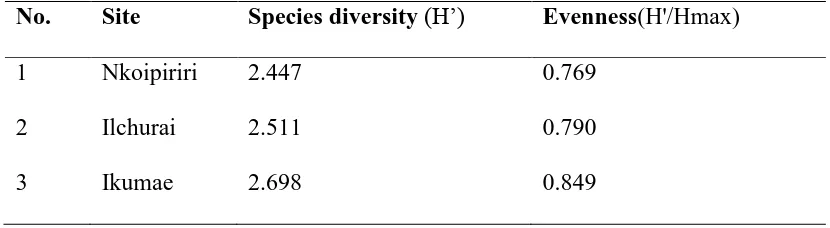

4.4. Diversity and evenness of Indigenous Medicinal Plants (IMPs) in the study sites ... 43

4.4.1. Species diversity in the study sites ... 43

4.4.2. Species evenness ... 44

4.5. Modes of utilization and harvesting of Indigenous medicinal plants among the rural communities in the study area ... 45

4.5.1. Mode of utilization of the identified common IMPs in the study areas ... 45

4.5.2. Other uses of IMPs in the study areas ... 49

4.5.2.1. Statistic Mean of Various utilization of IMPs ... 50

4.5.2.2. Correlation of use values of medicinal plants ... 51

4.6. Harvesting Techniques ... 53

4.6.1. Parts Used as IMPs ... 53

4.6.2. Quantity and frequency of harvesting medicinal plants ... 54

4.7. Conservation measures in place to conserve Indigenous medicinal plants of IMPs in the study areas ... 55

4.7.1. Habit of the common IMPs ... 55

4.7.2. Declining Species ... 56

4.7.3. Respondents‟ views on the importance of conservation ... 58

4.7.4. Herbalist view of the locally available IMPs ... 59

4.7.5. Threats to locally available IMPs ... 59

4.7.6. Suggested Conservation measures in the study areas ... 60

4.7.6.1. Restrictions on the harvesting ... 61

4.7.6.3. Cultivation of medicinal plants in the farms ... 62

4.7.6.4. Cultivation of other woody species ... 63

4.7.6.5. Setting aside a conservation area/preservation area ... 63

4.7.7. Activities carried out within the conservation area ... 64

4.7.8. Recommendations on what to be done so as to ensure conservation and sustainability of IMPs in the study area ... 65

CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ... 67

5.1. Introduction ... 67

5.2. Conclusions ... 67

5.3. Recommendation ... 68

5.4. Areas for future research ... 70

REFERENCES ... 71

APPENDICES ... 79

6.1. Questionnaire ... 79

6.2. Observations –photographs ... 85

6.3. Results of Eveness and Diversity in Ikumae site ... 93

6.4. Results of Eveness and Diversity in Koipirir site ... 94

6.5. Results of Eveness and Diversity in Ilchurai site ... 95

LIST OF TABLES

Table 4.1. Respondents Gender and Household headError! Bookmark not

defined.

Table 4.2. Households economic activity ... 39

Table 4.3. Composition of Indigenous Medicinal Plants in Koipiriri (K), Ikumae (IK) and Ilchurai(IL) areas ... 41

Table 4.4. Abundance of IMPs in the study areas (%) ... 42

Table 4.5. Species diversity H' and Evenness (H'/Hmax) for Koipirir, Ilchurai and Ikumae (Using Shannon Weiner Index) ... 43

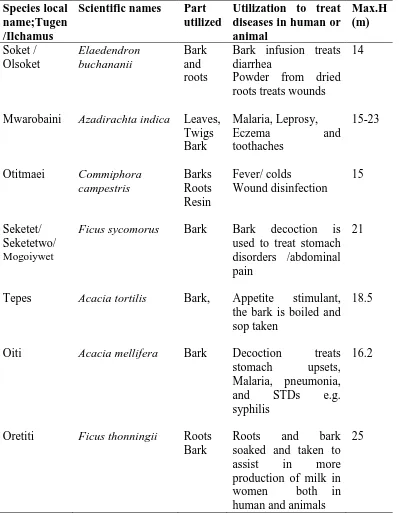

Table 4.6. Mode of utilization of the identified common IMPs-above14m H ... 46

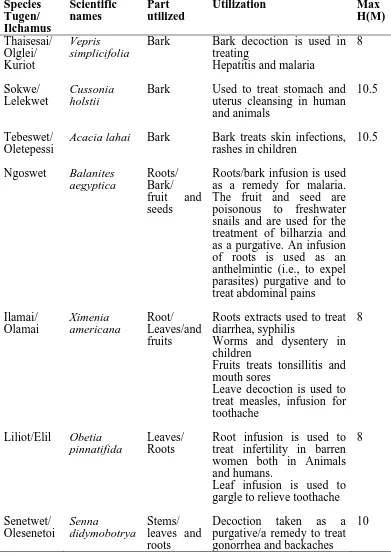

Table 4.7. Mode of utilization of the identified common IMPs 8-10.5m H ... 47

Table 4.8. Mode of utilization of the identified common IMPs 4.9-6.5mH ... 48

Table 4.9. Mode of utilization of the identified common IMPs 0.6-4.0m H ... 49

Table 4.10. Pearson Correlation of other uses of IMPs against Medicinal Use ... 52

Table 4.11. Quantity of medicinal plants harvested ... 54

Table 4.12. Threats to Locally available IMPs ... 60

Table 4.13. Impacts of setting aside a conservation area ... 63

Table 4.14. Activities carried out within the conservation area ... 64

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure1.1. Conceptual Framework on the utilization and conservation of

indigenous medicinal plants ... 8

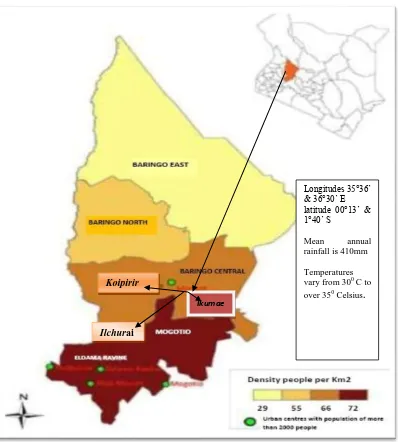

Figure 3.1. Map of Baringo Central showing Koipiriri, Ikumae and Ilchurai study areas ... 29

Figure 4.1. The age of the respondents at the study site ... 37

Figure 4.2. Respondents Education level at the study sites ... 38

Figure 4.3. Various utilization/exploitation modes of IMPs in the study area ... 50

Figure 4.4. Parts being utilized ... 53

Figure 4.5. Habit of the common IMPs in the study area ... 56

LIST OF PLATES

Plate 1 Azadirachta indica ... 85

Plate 2 Cussonia holstii ... 85

Plate 3 Albizia anthelmintica... 85

Plate 4 Vepris simplicifolia ... 86

Plate 5 Leonotis nepetifolia ... 86

Plate 6 Grewia tephrodermis... 86

Plate 7 Aloe secundiflora... 87

Plate 8 Senna didymobotrya ... 87

Plate 9 Aloe secundiflora... 87

Plate 10 Solanum incanum ... 88

Plate 11 Acacia lahai ... 88

Plate 12 Acacia nilotica ... 88

Plate 13 Acacia tortilis ... 89

Plate 14 Ficus sycomorus ... 89

Plate 15 Elaedendron buchananii ... 89

Plate 16 Zingiber officinale ... 90

Plate 17 Tamarindus indica ... 90

Plate 18 Ximenia americana ... 90

Plate 19 Obetia pinnatifida ... 91

Plate 20 Solanum aculeastrum ... 91

Plate 21 Maesa lanceolata ... 91

Plate 22 Acacia mellifera ... 92

Plate 23 Balanites aegyptica ... 92

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

ASAL Arid and Semi-Arid Land

BCI Biodiversity Calculator Index

CR Critically Endangered

DFO District Forest Officer

EN Endangered

IMP(s) Indigenous Medicinal Plant(s)

IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature

KEFRI Kenya Forest Research Institute

NMK National Museums of Kenya

PHC Primary Health Care

R Rare

SPSS Statistical Package for Social Sciences

STDs Sexually Transmitted Diseases

USAID United States Agency International Development

ABSTRACT

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background to the Problem

Increasing demand for medicinal plants internationally has resulted in the

over-exploitation and indiscriminate over-harvesting of medicinal plants (Dharani and

Yenesew, 2010). The degree of vulnerability of medicinal plants to

overexploitation and disturbance largely depends on the part used be it bark,

leaves, twigs, roots or stem and the life form (Fratkin, 1996). Indigenous

medicinal plants are particularly vulnerable to over-exploitation because they are

slow growing species and partly because of their scarcity (Giday et al., 2003).

The harvesting technique employed in the prevailing area is important in the

conservation of medicinal plants as some of the practices may be destructive. In

view of these threats to medicinal plants there is need for sustainable management,

cultivation and conservation of medicinal plants (WHO et al., 1993). According to

Giday et al., (2003), the conservation of African medicinal plant species is critical

for local health as well as for international drug development. As much as 95% of

African drug needs come from medicinal plants, and as many as 5000 plant

species in Africa are used for medicinal purposes (Taylor et al., 2001; Dharani and

According to Gauto et al., (2011), one of the major concerns of our times is the

loss of the Earth‟s biological diversity. The world‟s flora and fauna are facing an

alarming decline of its wild populations, mainly due to the loss of their natural

existing habitats. A lack of ecological knowledge can seriously hinder the

conservation and sustainable use of medicinal plant species, especially in the face

of anthropogenic threats such as overexploitation and land use changes.

Along with overexploitation, land use changes threaten many medicinal plant

species in Africa (Giday et al., 2003; Alves and Rosa, 2007). Research has shown

that medicinal plants with ruderal life history characteristics tend to be more

tolerant of habitat disturbance and degradation (Giday et al., 2003). The

insufficient knowledge about the conservation and sustainable use of medicinal

plants is a serious problem for resource managers. The creation of protected areas

may facilitate the conservation of medicinal plant species by reducing habitat loss

and, via restrictions on access and extractive use, reducing disturbance and

overexploitation (Okello et al., 2009; Ndangalasi et al., 2007).

The communities‟ knowledge on traditional medicine, changing lifestyles and

practices is also affecting the status of medicinal plants (Kiringe, 2005). It is

generally agreed that in the less developed countries like those of Africa, human

activities are taking a serious toll on renewable resources including plant species

Deforestation is one of the activities that have led to tremendous loss of important

plant resources in both the developed and developing countries.

Tremendous land use changes have taken place in the recent past in Baringo

County which made agriculture become popularized as in other areas, including

West Pokot and Samburu where medicinal plants are preferred as means of

treatment (Campbell et al., 2000), and this has the potential to undermine the

conservation of important plant resources to the community. Based on these

changes that appear to move swiftly across Baringo land, this study tried to

investigate the utilization and conservation measures of locally available

indigenous medicinal plants in Koipirir, Ilchurai and Ikumae in Baringo County.

1.2. Statement of the Problem and Justification of the Study

Unmonitored trade in medicinal plant resources, destructive harvesting techniques,

overexploitation, habitat loss and habitat change are the primary threats to

medicinal plant resources in most developing countries (IUCN, 2002). Also, the

plant parts used and the harvesting technique of medicinal plants affect plant

population, structure, availability and abundance. Cunningham (2000) indicated

that little is known about the sustainability of harvesting strategies being employed

currently in harvesting medicinal plants. The study area has little documented data

human and animal diseases, exploitation of medicinal plants for different uses and

also on the conservation strategies of these plants.

Anthropogenic activities such as deforestation in quest to get more land for

grazing, cultivation and charcoal making are being carried out in the study area

hence a threat to indigenous medicinal plants. According to the Institute of

Economic Affairs (2011), Baringo is the third County to seek for medical

treatment using medicinal herbs after Samburu and West Pokot. The vegetation of

Baringo County is an important source of local building materials, fuel wood and

also used as traditional medicines for the treatment of diseases in both human

beings and their livestock (WHO et al., 1993).

Due to lack of awareness, research and education in conservation of natural

resources and biodiversity, deforestation resulting in land degradation has been a

major problem of the area. Habitat loss is threatening the survival of many

important medicinal plants which in turn causes a great challenge in treating

human and livestock diseases such as headaches, toothaches, stomach problems

and other diseases as the rural communities depend on herbal medicine for primary

1.3. Research questions

The study was guided by the following questions:

(i) What is the composition and abundance of the common Indigenous

Medicinal Plants (IMPs) in Koipirir, Ikumae and Ilchurai in Baringo

County?

(ii) What is the diversity and evenness of Indigenous Medicinal Plants (IMPs)

in Koipirir, Ikumae and Ilchurai in Baringo County?

(iii) What are the modes of utilization and harvesting of Indigenous medicinal

Plants among the rural communities in the study area?

(iv) Which conservation measures are in place to conserve Indigenous

Medicinal Plants in Koipirir, Ikumae and Ilchurai?

1.4. Research Hypotheses

The study was guided by the following hypotheses:

(i) The composition and abundance of the common Indigenous Medicinal

Plants (IMPs) in Koipirir, Ikumae and Ilchurai is significantly diverse.

(ii)The diversity and evenness of Indigenous Medicinal Plants (IMPs) in

Koipirir, Ikumae and Ilchurai is significantly different.

(iii)The modes of utilization and harvesting of Indigenous Medicinal Plants is

significantly different in Koipirir, Ikumae and Ilchurai.

(iv)There are no measures in place to conserve Indigenous Medicinal Plants in

1.5. Broad objective

The broad objective of the study was to determine the utilization and conservation

of Indigenous Medicinal Plants among the rural communities in Koipiriri, Ikumae

and Ilchurai sites in Baringo County, Kenya.

1.5.1. The Specific objectives

The specific objectives were:

(i) To assess the composition and abundance of the common Indigenous

Medicinal Plants (IMPs) in Koipiriri, Ikumae and Ilchurai in Baringo

County.

(ii) To find out the diversity and evenness of Indigenous Medicinal Plants

(IMPs) in Koipiriri, Ikumae and Ilchurai in Baringo County.

(iii)To determine the modes of utilization and harvesting of Indigenous

Medicinal Plants among the rural communities in the study area.

(iv)To find out the conservation measures in place to conserve Indigenous

Medicinal Plants among the rural communities in Baringo County.

1.6. Significance of the study

The study will provide information on composition, abundance, diversity,

evenness, utilization and harvesting techniques of IMPs in Koipiriri, Ikumae and

Ilchurai. Thus, the information is important as it forms the basis of their

similar studies. The study also contributes to knowledge on the utilization,

harvesting and conservation measures of Indigenous Medicinal Plants.

1.7. Conceptual framework

This study conceptualized on the basis that medicinal plants are a valuable

biological resource that can be sustainably exploited or utilized and contribute in

measurable ways to better livelihood of the local community in the study area. In

general, there is a relationship between utilization of IMPs and their conservation.

On utilization, their uses are explained together with the parts used and modes

used. IMPs have threats which include deforestation, overgrazing, over harvesting,

genetic erosion etc. These threats affect conservation. Therefore, the following

Relationship

Figure1.1. Conceptual Framework on the utilization and conservation of indigenous medicinal plants

Threats

-Genetic erosion

-Erosion of traditional knowledge -Over harvesting

-Deforestation

-Increased human population

-Overgrazing and inadequate policies

UTILIZATION CONSERVATION

Uses/

Exploitation

-Treatment of human

1.8. Definition of operational terms

Abundance indicates the percentage of individuals within each species present in a community and how that species relates numerically to the abundance of any

other species present in that community. It also reveals ecological patterns that

indicate which species is dominant or least dominant on that specific site (WHO,

2012).

Bark is outermost layer of stems and roots in woody plants; all tissue outside the cambium.

Correlation between sets of data is a measure of how well they are related. The most common measure of correlation in statistics is the Pearson Correlation. It

shows the linear relationship between two sets of data.

Composition in this study refers to the common species that are available in the study area.

Diversity refers to the quality of being different or with variety. It can be described as the product of the richness or variety of entities (usually species) and

the variance of that richness or its importance value.

Ecology is the study of the interaction of organisms with each other and with their environment.

Ecosystem is the total of all organisms and their interaction with each other, habitat and environment within a specific area.

Herb is a plant without a persistent woody stem above ground.

Herbalist is a person who treats diseases by means of medicinal herbs and is mainly referred to as herb doctor.

Indigenous means that something is originating locally and performed by a community or society in a specific place. It emerges as peoples‟ perceptions and

experience in an environment at a given time in a continuous process of

observation and interpretation in relation to locally acknowledged everyday

rationality and transcendental power.

Indigenous Knowledge is human life-experience in distinct natural and social compound within unique local and contemporary setting. It is not formally taught

but perceived in a particular context at a certain stage of the perceiver‟s

consciousness that grows in the world of local events.

Indigenous Knowledge System is the inter-relationship developed and maintained by indigenous people using their own system of knowledge suitable to

their environment, underutilized and valuable for their livelihood, which is the

basis for local level decision-making in agriculture, education, natural resources

management and the host of other activities in rural communities. It is dynamic

and is continually influenced by internal creativity and experimentation as well as

by contact with external systems (Institute of Economic Affairs, 2011).

Population refers to all individuals of a particular species in a given area.

always not available to local inhabitants. It is retained within them, modified over

time and transferred to the next generation.

Shrub is a self-supporting woody plant branching at or near the ground or with several stems from the base.

Species refers to Linnaean unit of plant classification; group of populations of similar morphology and constant distinctive characters, thought to be capable of

interbreeding and producing offspring.

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW

Traditional medicinal plants are important source of local building materials, fuel

wood and also used for the treatment of diseases in both human beings and their

livestock in developing countries where 80% of the population has been reported

to depend on traditional medical systems (Dharani and Yenesew, 2010; Dharani et

al., 2010; Njoroge et al., 2010). The use of herbal medicines however, is on the

increase even in developed countries because of the belief that herbal remedies are

safe because of their natural origin. Globally, there are about 120 plant-derived

drugs in professional use; three quarters being obtained from traditional medicinal

plants (Fabricant and Farnsworth 2001).

2.1. Overview of traditional Medicinal Plants

In developing countries, it has been estimated that up to 90% of the population rely

on the use of medicinal plants to help meet their primary health care needs (WHO,

2002). Apart from the importance in the primary health care system of rural

communities, medicinal plants also improve the economic status of the people

involved in their sale in markets all over the world (Taylor et al., 2001). In Kenya,

traditional medicine has still continued to play a major role as a source of local

building material and fuel wood and in Primary Health Care (PHC) for example

Acacia lahai is used to treat skin infections as well as used as firewood by the

malaria as well as a source of firewood and at times timber by many communities

(Arwa et al., 2010).

More than 70% of the Kenyan population relies on traditional medicine as its

primary source of health care, while more than 90% use medicinal plants at one

time or another (Dharani and Yenesew, 2010; Dharani et al., 2011). This is

because of the accessibility to the traditional medicine as compared to modern

health facilities for most of the population in the country and it is relatively

inexpensive, locally available, and usually accepted by the local communities as

compared to modern conventional medicine.

Although there have been intensive efforts to identify medicinal plants and explore

their biochemistry (Fabricant and Farnsworth, 2001; Fennell et al., 2004), very few

studies have investigated the conservation biology of medicinal species. A major

constraint being faced in obtaining information about medicinal plants in the

marketplace, however, lies in the difficulty of identifying many of the species

being sold. In many medicinal plant shops, piles of barks, roots, and herbs are

unlabeled and lack identifying characteristics of fruit, flower, or leaf (Kipkore et

al., (2013).

According to Gauto et al., (2011), one of the major concerns of our times is the

alarming decline of its wild populations, mainly due to the loss of their natural

existing habitats. A lack of ecological knowledge can seriously hinder the

conservation and sustainable use of medicinal plant species, especially in the face

of anthropogenic threats such as overexploitation and land use changes. Along

with overexploitation, land use changes threaten many medicinal plant species in

Africa (Giday et al., 2003; Alves and Rosa, 2007). Research has shown that

medicinal plants with ruderal life history characteristics tend to be more tolerant of

habitat disturbance and degradation (Giday et al., 2003; Shanley and Luz, 2003;

Voeks, 2004).

The insufficient knowledge about the conservation and sustainable use of

medicinal plants is a serious problem for resource managers (Ayaad, 2003). The

creation of protected areas may facilitate the conservation of medicinal plant

species by reducing habitat loss and, via restrictions on access and extractive use,

reducing disturbance and overexploitation (On et al., 2001; Ndangalasi et al.,

2007). According to Njoroge et al., (2010), in Kenya, 90% of the population has

used medicinal plants at least once for various health conditions. Also 95% of the

population has used medicinal plants as firewood or timber with and without

knowing. In other regions such as Peru, it has been found that about 84% of the

local people prefer traditional medicinal plants for their health care needs in

the fact that they are of natural origin and no risks or harm is experienced when

used (Bussman et al., 2007).

Hamilton, (2009), indicated that almost one third of medicinal plant species could

become extinct, with losses reported in China, India, Kenya, Nepal, Tanzania and

Uganda. Greater losses are expected to occur in arid and semi-arid areas due to

factors such as: climate change, erosion, expansion of agricultural land, wood

consumption, and exploitation of natural vegetation, increased global trade in

natural resources, domestication, selection and grazing among other factors

(Weizel and Rath, 2002).

2.2. Arid and Semi-Arid Lands and Indigenous Medicinal Plants

In Kenya, arid and semi-arid land (ASAL) ecosystems are globally significant

repository of biodiversity (including indigenous medicinal plants) and are

acclaimed for their species richness and habitat diversity, Baringo County

included. Other ASALs, in Kenya include Garissa, Isiolo, Mandera, Marsabit,

Moyale, Samburu, Tana River, Turkana and Wajir counties. ASALs account for 88% of the land‟s surface area and are home to over 10 million people (Njoroge et

al., 2010). These areas are facing intense degradation due to pressure arising from

It is estimated that 70% of Kenya‟s rural population use a combination of

traditional and modern medicine, with a larger percentage using indigenous

medicinal plants for other uses such as firewood, charcoal, and as income

generating mechanism (Lekoyiet, 2006) and the traditional knowledge of

medicinal plants is most often passed down within families and communities from

generation to generation. According to Sindiga et al., (1995), high dependence on

traditional medicine revolves around its ability to meet four criteria of “accessibility, availability, acceptability and dependability”. High rate of reliance

on medicinal plants in Kenya comes about due to the inability to reach modern

health facilities even in urban areas where supplements to western forms of

medicine are available (Pandit and Babu, 1998).

For thousands of years worldwide, plants have been used in traditional medicine,

resulting in the development of a large body of local knowledge. This knowledge

base arises primarily from trial and error experiences and is rarely embedded in

complete and systematic theories of medicine (Bo et al., 2003). In many cases,

local knowledge of medicinal plants remains poorly documented in the scientific

literature. For example, in a study of herbs used for medicinal baths among the

Red-headed Yao in China, only 5% of 110 species registered had been previously

identified as having medicinal properties, and 79%were newly recorded for their

Local knowledge of how medicinal plants are used may be a rich basis for the

phytochemical, pharmacological, and clinical studies necessary to secure

sustainable and rational use of these plants as a resource (Taylor et al., 2001). In

addition to the limited documentation, much traditional medical plant knowledge

is being lost before its incorporation into modern science. Environmental

degradation and large changes in modern social and economic systems have

affected medicinal plant use over the past few decades (Kipkore et al., 2013). A

study of medicinal plants of the Zay in Ethiopia reported the use of 33 species, but

the informants all agreed that more species had been used in the past. It was

suggested that deforestation, degradation, and acculturation over many years

caused the reduction (Giday et al., 2003). Likewise, in northwestern Yunnan in

China, over-exploitation and deforestation are depleting the medicinal plants used

by the Lisu (Ji et al., 2005).

2.3. Threats to Traditional Medicinal Plants

The most serious threat to local medicinal plant knowledge, however, appears to

be cultural change, particularly the influence of modernization and the western

worldview (Voeks and Leony, 2004). Knowledge loss has possibly also been

aggravated by the expansion of modern education, which has contributed to under-

mining traditional values among the young (Giday et al., 2003). Bussmann and

Sharon (2006), based on a study of medicinal plant knowledge in southern

evolved in traditional cultures over hundreds of years, and to keep it alive, it is

necessary to document and describe traditional use of plants.

Accordinf to Farnsworth et al., (1985) many researchers have made the

assumption that all plants mentioned as useful are also actually being used. But a

few studies have teased apart what people say and what they do, and it turns out that the “local knowledge,” represented by what the informants tell the researcher,

is not always equal to “local use,” which refers to which plants and which uses are

actually practiced (Byg and Balslev, 2001). This gap between local knowledge and

local use can be taken as the first sign of degradation of traditional ethno botanical

knowledge and can be used to measure loss of knowledge (Reyes-García et al.,

2005).

The high anthropogenic pressures and associated fragmentation of the landscapes

has resulted in loss of habitat and species (Altmann et al., 2002). Under these

conditions, medicinal plants are also being under constant threat due to over

exploitation from natural habitats even in the absence of cultivation (Njoroge et

al.,2010). During periods of food scarcity in the dry areas of Kenya or during

famines the poor rural communities harvest wild plants, including fruits and leaves

for food (Pascaline et al., 2010). The type of plants and parts removed vary from

one locality to another and their use depends on the local indigenous knowledge

Deforestation caused by the need for human settlement and allied infrastructure

development and cultural expansion, charcoal production, timber sales and

overgrazing have further caused the shortage of herbal plants (Hosier,1988).

Deforestation directly reduces the biodiversity of wild plant resources and

indirectly so through the loss of the habitat areas as well as other organisms

important for ecosystem function (Njoroge, 2012). Demand for herbal products

however, is on the increase, exerting a lot of pressure on the remaining indigenous

medicinal plants (Lykke et al., 2003). This calls for the need to devise strategies to

increase the supply of these resources as well as protecting the source habitats. The

major threat in the conservation of medicinal plant can be given as deforestation,

human density and biodiversity risk, land tenure policies, erratic rainfall and

droughts and impact of livestock grazing (Njoroge, 2012).

2.3.1. Deforestation

The vegetation of Baringo County is important source of local building material,

fuel wood and also used as traditional medicines for the treatment of diseases in

both human beings and their livestock (Bryan, 1994). The Tugen and Ilchamus

pastoralists rely on IMPs for healthcare in both human beings and their livestock.

IMPs are not only used in primary healthcare but also means of generating income

for several traditional herbalists in this area (Cunningham, 2001). Currently, in the

rate at which old indigenous tress are cut down and forests are being destroyed for

unsustainable logging and making charcoal. Deforestation results in land

degradation and catastrophic habitat loss are threatening the survival of many

important medicinal plants (Giday et al., 2003). This poses an acute challenge to the survival of their livestock and local community‟s livelihood.

According to Njoroge (2012), rural farmers may be responsible for clearing land,

but rural firewood users rarely cause deforestation. While urban charcoal users

may contribute more to the process, they frequently purchase charcoal produced

from surplus wood left after the clearance of land for agriculture (Reta,2012). In

both cases where trees are felled to provide fuel and trees; agricultural land,

economic development seems to lead inevitably to environmental deterioration

(McGeoch et al., 2008).

Species like Balanites aegyptica, Acacia tortilis and Acacia mellifera have been

observed to be on decrease on ASALs such as in Mwingi, Machakos and Narok

due to anthropogenic factors including deforestation and over exploitation

(Njoroge et al., 2010).

Srithi et al.,(2009) indicated that the primary causes of deforestation can be the

clearance of land for agricultural production and the harvesting of wood for fuel.

energy balance for all the countries in this region (Hosier, 1988). Thus, wood fuel

consumption places a major pressure on forest resources.

2.3.2. Human density and biodiversity risk

The driving forces behind land transformation resulting biodiversity losses include

mainly growth of the human population and its greater demand for resources. The

link between high human population densities and risk to biodiversity is mainly

indirect, but are nevertheless linked (Cincotta et al.,2000). The correlation of

human density with forest cover suggests that increasing human population density

may make forests vulnerable as they are converted to agricultural or urban areas,

or logged to provide timber. In addition, forests in heavily populated areas also

remain vulnerable to overharvesting (Cunningham,2000).

2.3.3. Land tenure policies

Ill-defined tenure rights over forest adjoining or in nature reserves also make

effective forest management impossible. In the study conducted by Sodhi et al.,

(2010), user rights for conservation areas are not well-defined or difficult to

enforce. Vijay (2006) indicates that disputes over grazing rights between villages

in Nujiang and Diqing prefectures have continued for decades. In 2000, the alpine

pasture was adjudicated by a provincial agency to belong to Diqing, but villagers

in Nujiang continue to contest the decision. Fearing that a conflict may erupt,

degradation of pasture in those areas. In both cases, difficulties in enforcing tenure

rights have adverse impacts on biodiversity (Garcia, 2006)

Moreover, the study in Southeast Asia by Sodhi et al., (2010), sudden changes in

tenure policy have historically been related to increases in the use of forest

resources and even clear-felling. The introduction of the household responsibility

system and forestland allocation policies in the early 1980s are two examples of

forest tenure policy changes which in many sites led to excessive felling of timber,

from which the forest has still not recovered.

2.3.4. Erratic Rainfall and Droughts

The degraded lowlands of Baringo County exemplify the challenges experienced throughout Kenya‟s dry lands (Bryan, 1994). Seventy per cent of Baringo County

is arid or semi-arid unproductive land (Wahome, 1984) due to soil erosion which

leads to loss of vegetative cover.

Erratic rainfall in the County causes increased water run-off and flash floods when

it fall (Institute of economic affairs,2011). Also the intensive storms are worsened

by deforestation, as well as intensified grazing which threatens the medicinal

plants in the study areas, (Lekoyiet, 2006).

2.3.5. Impact of livestock grazing

Free grazing of livestock is another threat to the viability of medicinal plant

degradation of pastures containing numerous medicinal plants, herbs and shrubs.

(Seno and Shaw, 2002). Also, expanding agriculture is also contributing to the

elimination of many medicinal plants. The study by Xu and Wilkes (2004)

indicated that, more than 80% of the total population in Northwest Yunna of

Astore valley is highly dependent on agriculture and livestock for its livelihood,

thus putting tremendous pressure on pastures and associated natural resources. Due

to limited cultivable land there is rapid encroachment of forests and pastures

(Harms et al., 2001).

2.4. Health seeking and use of herbal medicines

The substantial contribution to both socio-economic and human health and

well-being made by traditional medicinal plant species is now widely appreciated and

understood (Njoroge, 2012). Indeed, there is a growing demand for many of the

species and an increasing interest in their use. This, combined with continued

habitat loss and erosion of traditional knowledge, is endangering many important

medicinal plant species and populations and creating an urgent need for improved

methods of conservation and sustainable use of these vital plant resources

(Leamann et al., 1999).

The incidence of diseases in Baringo remains quite high approximately at 34%

according to Institute of Economic Affairs, (2011). The main diseases by the

chest, lungs and skin problems. Most of the residents in these areas still value

IMPs as a form of treatment.

2.5. Use of indigenous medicinal plants in various communities in Kenya

Several communities value IMPs for the treatment of diseases both in human and

animals (Njoroge, 2012). For example in the Nyanza region in Gwasi Hills, the

Abasuba local community is widely known for using herbal and forest products in

traditional rituals of rain making or ritual cleansing alongside other medicinal uses

including remedies for common ailments such as headaches, malaria fever,

stomach aches, etc. (Institute of Economic Affairs, 2011). In the western region,

the Luhya community around the Kakamega Forests also use the forest resources

as a source of health remedy to diseases such as malaria, stomach aches, cancer,

appetizer and vigour booster etc. (Odera, 1997). In the coast region, the Gede

community are known to use the IMPs found in the Gede forest to cure different

types of diseases (Kamau, 2009).

2.6. Composition of medicinal plants

Medicinal plants species found in different areas usually vary depending on factors

such as climate, soils and the vulnerability to anthropogenic factors (WHO, 1999).

The beneficial medicinal effects of plant materials typically result from the

combinations of secondary products present in the plant and more than 50,000

al., 2002). The medicinal actions of plants are unique to particular plant species or

groups in a particular plant and are often taxonomically distinct (Wink, 1999). In

many studies on medicinal plants, local and scientific names are used to identify

the composition of IMPs.

2.7. Abundance of Medicinal plants

The abundance of a plant species is usually the percentage of individuals within

each species present in a community and how that species relates numerically to

the abundance of any other species present in that community (WHO,2012). It also

reveals ecological patterns that indicate which species is dominant or least

dominant on that specific site.

The results of species abundance and scarcity are used to inform what kind of

conservation measures should be taken in an area. According to Odat et al., 2009,

disturbed and fragmented habitats are usually dominated by a very few species

compared to the undisturbed sites.

2.8. Medicinal plants diversity and conservation

Biological diversity can be described as the product of the richness or variety of

entities (usually species) and the variance of that richness or its importance value.

heterogeneity (Addo-Fordjour et al., 2008). Biological diversity also can be

appreciated by the number of endemic species whose distributions are restricted to

a confined geographic area (Robert et al., 1995). In recent years, public attention

has been given to diversity at the world level. The diversity of medicinal plants

mainly gives priority to conservation of medicinal plants (Barbhuiya, 2009).

In studies of IMPs, the observed species diversity is affected not only by the

number of individuals but also by the heterogeneity of the sample (Sodhi et al,

2010. If individuals are drawn from different environmental conditions (or

different habitats), the species diversity of the resulting set can be expected to be

higher than if all individuals are drawn from a similar environment. Increasing the

area sampled increases observed species diversity both because more individuals

get included in the sample and because large areas are environmentally more

heterogeneous than small areas (Odum, 1971).

2.9. Utilization of IMPs

Medicinal plants can be taken as decoctions where the plant parts are boiled or

simply soaked in water and the decoction taken alone, or in some instances

combined with honey, soup, or milk if the decoction is from a bitter plant (Jeruto

et al, .2008). The soup is made from the head, intestines and hooves of an animal,

herbs may also be used depending on the condition being treated and the

concoction administered to the patient.

Again, they can be taken in form of ashes where leaves are dried and burnt to form

powder ash (Okello et al., 2009). The ashes may then be licked, or in some

instances applied on incisions that are made on the skin to treat particular ailments.

In other cases the green leaves are crushed, and sometimes soaked in water and the

resultant concoction may be drunk, or applied directly on the affected area such as

in the treatment of toothache. The latex may also be applied on the affected area of

the skin, an example being in the treatment of allergy (Kipkore et al., 2013).

Apart from the indigenous medicinal plants being taken as medicine, other uses

include being used as firewood, source of timber, shade, fencing trees and at times

CHAPTER 3: METHODOLOGY 3.1. Introduction

This chapter describes the study area, study location, selection of the study site,

methods of data collection, methods of data analysis and presentation.

3.2. Study area

The study area is Koipiriri, Ilchurai and Ikumae sites in Baringo Central

Constituency, Baringo County.

3.2.1. Study area location

Baringo County is situated between longitudes 35°36‟ and 36°30‟ East and

between latitude 00°13‟ and 1°40‟ south. Baringo County is to the southern part of

the entire Rift Valley region and borders Nakuru to the South, Turkana County to

the North, Samburu and Laikipia Counties to the East and Elgeyo Marakwet

County to the West (Figure 3.1).

3.2.2. Climate and Relief

The climate of the area is influenced by relief. The altitude varies from 300m at

the plains to 1,000m above the sea level. The rainfall is bimodal with short rains

being experienced between November to January and long rains in March to May.

The mean annual rainfall is 410 mm. Temperatures vary from 300 C and

temperatures of above 300 C. The coldest months have temperatures ranging from

160 C to 180 C but can drop to as low as 100 C (Ministry of State Development of

Northern Kenya and other Arid Areas, 2009).

Figure 3.1. Map of Baringo Central showing Koipiriri, Ikumae and Ilchurai study areas

(Source: Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, 2000).

Koipirir

Ilchurai

Ikumae

Longitudes 35°36‟ & 36°30‟ E latitude 00°13‟ & 1°40‟ S

Mean annual

rainfall is 410mm

3.2.3. Vegetation

The vegetation is characteristic of a dry savannah. The natural vegetation consists

of several species of acacia and grasses. Common tree species are Acacia tortilis,

Acacia seyal, Acacia nilotica, Acacia brevispica, Acacia mellifera and other acacia

species. Other species include Balanites aegyptica, Tarconanthus comphratus and

Terminalia. The grasses found in the area are Cynodon, Digitaria, Hyperhenia and

Cenchrus sp. (Wetangula et al., 2010). Baringo Central specifically consists of

traditional medicinal plants which can survive the harsh climatic conditions as the

area is an ASAL (MoE, 2000).

3.2.4. Soils and drainage

The soils in the area are sandy and poor in humus. There are several seasonal

rivers which flow from the hills to the escarpments through very deep gorges. One

of the prominent river valleys is the Kerio Valley which is fairly a flat plain. In the

eastern part of the county near Lake Baringo and Bogoria is the Liboi Plain

covered mainly by the latchstring salt-impregnated silts and deposits (MoE, 2000).

3.2.5. Economic activities

The main economic activity in the area is agriculture with pastoralism being the

most practiced. The livestock kept include goats, hardy cows, and few sheep and

in some places camels as there are large grazing pastures. Irrigated agriculture is

pawpaws, passion fruits and maize mainly as food crops and for income generation

(Insitute of Economic Affairs, 2011).

3.2.6. Population of the Study area

The population of Baringo County is 555,561 people and Baringo Central Sub

County is 80,871 and 15,730 in Ilchamus Ward (Population census, 2009). The

tribes consist of Tugen (Samor) mainly from the upper regions that is the south,

south east and south west and Ilchamus mainly from the low regions northwards

and at the western Pokot communities who are mainly pastoralists and the main

economic activity has remained semi-nomadic pastoralism with the vast majority

relying on livestock.

3.3. Research design

3.3.1. Selection of the Study Area

The actual study was preceded by a preliminary survey. The aim of the

preliminary survey was to test the instrument to be used in the actual study, collect

background information on the Indigenous medicinal plants and assess the

accessibility of the study sites. During the survey, it was found out that the

indigenous medicinal plants were mainly found in five areas in Baringo Central,

Baringo County (Koipiriri, Namunyak, Ilchurai, Naserian and Ikumae). Only 3

sites were purposefully chosen for the study because of their accessibility and the

3.4. Sampling procedure

Prior to the sampling, the local administration informed the researcher that

approximately 50% of the houses had been displaced due to high state of cattle

rustling and the drought which had made people look for greener pastures in other

areas. In each study site questionnaires were administered randomly to 32

households per study site (using the Fischers equation Formula) to collect data on

common IMPs used to treat /human and animal disease and other uses, their

names, method of administration, part used, availability, modes of exploitation and

conservation strategies which are in place. Herbalists who had at least a structure

to administer/sell the medicine were purposefully selected in the nearby markets of Murda, Ntepes, Lororo and Ngo‟swe and were systematically interviewed. In total

twelve herbalists were interviewed. Purposive sampling was used to select the key

informants who included the Ecosystem Conservator, a Botanist, a District Forest

Officer (DFO) and a registered herbalist because they know about the area and

were conversant about the local culture.

3.5. Data collection

Primary data was mainly through use of questionnaire, key informants, interviews,

observations and photography.

3.5.1 Administration of questionnaires

The semi structured questionnaire was used to obtain information on utilization,

study area. In total 96 questionnaires were randomly administered to the

households with the assistance of three trained research assistants who understood

the local language and culture of the respondents. The household number was

arrived by using the formulae below:

(Fisher et al. 1991)

Where n=sample size, z score =1.96 for a confidence limit of 95%, p is the

standard deviation (in this study was 0.021), d = degree of desired precision of 0.5

and q=1 - p.

The questionnaires were administered to the household head (male) and where the

male was not present then the female head was allowed to fill. After explaining the

purpose of the study and obtaining oral prior informed consent, interviews were

undertaken. The questionnaires were written in English but translated in Tugen

and or Ilchamus local language by the research assistants in cases where the

interviewee indicated that they could not read/write. The questionnaires were

administered and collected once it was completed. Also 12 herbalists in the nearby markets of Murda, Ntepes, Lororo and Ngo‟swe were purposeful selected and the

questionnaires were systematically administered to them.

3.5.2 Transects

Plot based line transects were used where the composition, abundance, evenness

a quadrant was used on both sides of the transect 50m from the main transects thus

forming 50 by 50 meter grids, which were assigned a number. Six plots, 15 long

transects (500m long) and 150 quadrats were taken for each study site therefore in

total 45 transects were used forming 450 quadrats. In each quadrat, all plants

identified as used for medicinal purposes were numbered. A botanist helped to

identify the plants. Identification was also done using the relevant taxonomic

literature on the Flora of Tropical East Africa (Njoroge et al., 2010).

3.6. Data analysis and presentation

Data obtained from the questionnaires was captured in SPSS version 20.0; coded

and analyzed mainly using descriptive statistics and Pearson Correlation was used

to compare between medicinal use and other uses. Data on IMPs abundance were

captured and analyzed using Biodiversity Calculator Index (BCI). The abundance

of the locally available IMPs was calculated in terms of percentage abundance.

Shannon Weiner Index was used to calculate Species diversity and evenness. The

CHAPTER 4: RESULTS AND DISCUSIONS 4.1. Introduction

This chapter presents results and discussions from the findings. The chapter also

compares the results of the study and those of other similar studies.

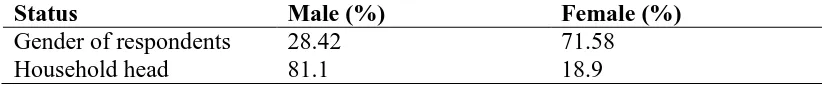

4.2. Respondents profile and background 4.2.1. Gender of the respondents

The study showed that female respondents were 71.58% while male respondents

were 28.42% (Table 4.1). The high percentage of women (71.58%) could be

attributed to the fact that the study was conducted at homestead level and during

the day when most women stay at home while men are away in the grazing fields.

The distribution above therefore does not necessarily reflect the population gender

distribution in the study area. According to the population structure for 2012 based

on the 2009 population and housing census, the ratio of male to female in Baringo

County is 1.01:0.99.

Table 4.1. Gender and Household head

Status Male (%) Female (%)

Gender of respondents 28.42 71.58

Household head 81.1 18.9

4.2.2. Household head

The study showed that 81.1% of the household were headed by men and 18.9% by

attributed to the strong culture and tradition of the community which states that “a

man is the head of the home / family and the woman can only take up the role after

the death of the husband. It is also a taboo and an abomination for a woman to

disrespect the husband or take his leadership role in the family” (Source: the

respondents).

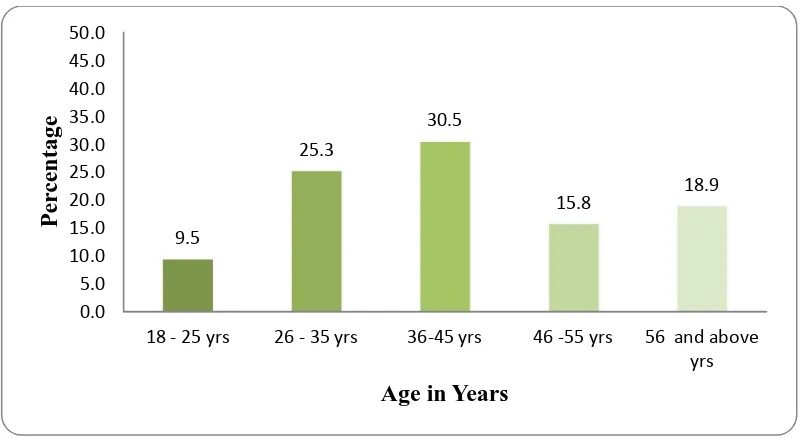

4.2.3. Ages of the respondents

For this study, ages of the respondents were important so as to identify those in

position to recognize the use and conservation of IMPs. 18.9% of the respondents

were 56 years of age and above, while 15.8% accounted for respondents between

46-55 years, 30.5% were 36-45 years, 25.3 % of the respondents 26-35 years and

9.5% were between ages 18-25 years (Figure 4.1). Approximately 90.5% of the

respondents therefore were between ages 26 and 55 years.

The study showed that ages 36-45 (30.5%) of the respondents were more involved

Figure 4.1. The age of the respondents

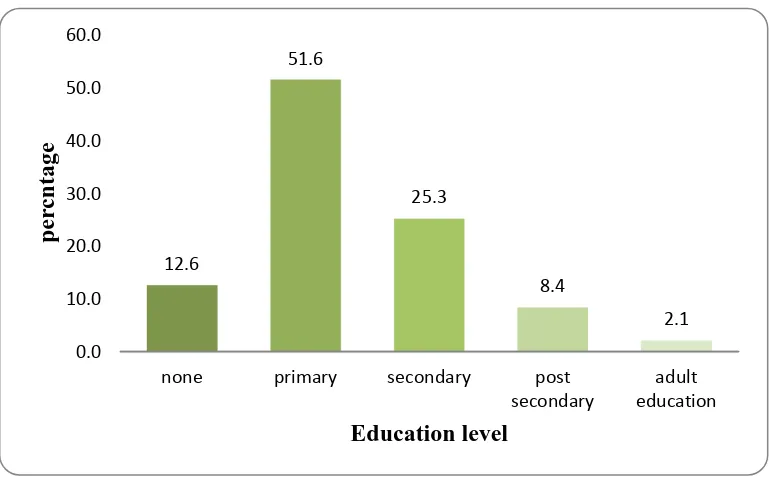

4.2.4. Education Level

The study showed that 51.6% of the respondents had attained primary education as

their highest level of education, 25.3% secondary school education while 12.6%

had never gone to school, 8.4 % had attained post-secondary education and only

2.1% had attained adult education (Figure 4.2).

Baringo Central being in an ASAL area, attaining even secondary education is a

great challenge because of the disturbance of floods, community strife, droughts

and pastoralism which usually make families move from one place to another.

Therefore, these findings are a true reflection of one of the many challenges the

rural communities in the study area undergo in their day to day lives. Also these

findings are in line with findings by the Kenya Population and Census, 2009 which 0.0 5.0 10.0 15.0 20.0 25.0 30.0 35.0 40.0 45.0 50.0

18 - 25 yrs 26 - 35 yrs 36-45 yrs 46 -55 yrs 56 and above yrs 9.5

25.3

30.5

15.8 18.9

P er ce n tage

showed that 69% of Baringo residents had attained primary education level while

3.4% post-secondary education.

Figure 4.2. Respondents Education level at the study sites

4.2.5. Household Economic Activity

The study showed that the main economic activity in the study area that brought

income to the household was pastoralism with 48.9%, agro-pastoralism 30.2%,

agriculture 11.5% and the least activity was extraction and selling of medicinal

plants which contributed to 9.4%. Pastoralism formed the main economic activity

and this could be attributed to the climatic conditions experienced in the area

which is mostly dry throughout the year with mean annual rainfall of 410mm. This

makes people move with their livestock from one place to another in search of

green pastures and water, agriculture done only along the rivers and medicinal

plants obtained far from the homes. According to Kitur (2009), pastoralism is 0.0 10.0 20.0 30.0 40.0 50.0 60.0

none primary secondary post

practiced in areas which have harsh climatic conditions and scarce water

availability.

Table 4.2. Households economic activity

Economic activity Frequency Percent (%)

Pastoralism 47 48.9

Agro- pastoralism 29 30.2

Agriculture 11 11.5

Extraction of medicinal plants and selling

9 9.4

Total 96 100.0

This study agrees with a report by Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of

Planning and National Development (2005/2006) which indicated that 62% of the

residents in Baringo are absolute poor and 34% are hardcore poor. The study also

found out the rural communities of in the study areas of Baringo County are still

practicing pastoralism and even though 51.6% had attained primary education they

are still absolute poor.

4.2.6. Preferred means of treatment

The study revealed that the preferred means of treatment was use of IMP with 84%

while 16% preferred modern medicine. This is the case because of easy

accessibility to the traditional medicine as compared to modern health facilities for

are relatively inexpensive, locally available, and usually accepted by the local

communities as compared to modern conventional medicine (Njoroge et al., 2010;

Odera, 1997). This study compares well with a study by Dharani et al., (2011)

which shows that large area of the country especially ASALs rely on traditional

medicine as its primary source of health care, while more than 90% use medicinal

plants at one time or another.

4.3. Composition and abundance of the common Indigenous Medicinal Plants (IMPs) in Koipiriri, Ikumae and Ilchurai

4.3.1. Composition of the Common IMPs in the study areas

The study revealed that the composition of IMPs in the study areas varied (Table

4.3). All the studied medicinal plants were found in the three areas. Solanum

incanum and Ximenia americana were absent in Ilchurai while Azadirachta indica

and Vepris simplicifolia were absent in Ikumae. However in the IUCN Red List

2015 of Species, the above absent species are not indicated as threatened.

The absence of these species could be attributed to the harsh climatic changes

such as the prolonged dry periods that have been taking place especially in the

ASALs of Baringo (Lekoyiet, 2006), which could affect the soil hence their

unavailability. Also the unavailability of plants such as Solanum incanum,

Azadirachta indica and Ximenia americana could be attributed to the fact that they

Table 4.3. Composition of Indigenous Medicinal Plants in Koipiriri (K), Ikumae (IK) and Ilchurai(IL) areas

Species Local name (Tugen/Njemps)

Scientific names Presence (p), Not present(n) K IL IK

Mwarobaini Azadirachta indica p p n

Sokwe /Lelekwet Cussonia holstii p p p

Otonwo/Lemukutan Albizia anthelmintica p p p

Olglei/Kuriot Vepris simplicifolia p p n

Chuchuniet Leonotis nepetifolia p p p

Sitet/OlSitete Grewia tephrodermis p p p

Chepkumiande /Olabai Psidia punctulata p p p

Senetwet/Olesenetoi Senna didymobotrya p p p

Tengeretwo/Tangeretwet Aloe secundiflora p p p

Ntulelei/Endulelei/Tawolwot Solanum incanum p n p

Tebeswet/Oletepessi Acacia lahai p p p

Lorityet/OlKiloriti Acacia nilotica p p p

Tepes Acacia tortilis p p p

Seketetwo/Mogoiywet Ficus sycomorus p p p

Soket /OlSoket Elaedendron buchananii p p p

Tangawizi/Lemunyi Zingiber officinale p p p

Tamarinds Tamarindus indica p p p

Ilamai/lamaek Ximenia americana p n p

Elil Obetia pinnatifida p p p

Sigowet /Osigawai Solanum aculeastrum p p p

Kipnandi /Kibabstaniet Maesa lanceolata p p p

Oiti Acacia mellifera p p p

Ngoswet Balanites aegyptica p p p

Otitmaei Commiphora campestris p p p

4.3.2. Abundance of IMPs in the study sites

The study revealed that the abundance of the species in the study areas was varied