1333

C

ognitive impairment resulting from vascular or neurologi-cal abnormalities is an important issue for countries with an increasing number of elderly people. As shown in Table 1 of the review by Elias et al,1 many longitudinal studies reported a positive association between blood pressure (BP) and future cognitive decline.2,3 However, most previous prospective stud-ies were based on conventional BP measurements.1 No studies have investigated the association between home BP and cogni-tive decline.Home BP measurements are more reproducible,4 more indicative of target organ damage,5 and have greater prognostic significance than conventional BP measurements, even when the number of measurements is the same or less when com-pared with conventional BP measurements.6 Our recent study, the multicenter Hypertension Objective Treatment Based on Measurement by Electric Devices of BP (HOMED-BP), demonstrated that home BP provided a more reliable estimate of a patient’s true BP than conventional BP measurements

See Editorial Commentary, pp 1163–1165

Abstract—Although an association between high blood pressure and cognitive decline has been reported, no studies have investigated the association between home blood pressure and cognitive decline. Home blood pressure measurements can also provide day-to-day blood pressure variability calculated as the within-participant SD. The objectives of this prospective study were to clarify whether home blood pressure has a stronger predictive power for cognitive decline than conventional blood pressure and to compare the predictive power of the averaged home blood pressure with day-to-day home blood pressure variability for cognitive decline. Of 485 participants (mean age, 63 years) who did not have cognitive decline (defined as Mini-Mental State Examination score, <24) initially, 46 developed cognitive decline after a median follow-up of 7.8 years. Each 1-SD increase in the home systolic blood pressure value showed a significant association with cognitive decline (odds ratio, 1.48; P=0.03). However, conventional systolic blood pressure was not significantly associated with cognitive decline (odds ratio, 1.24; P=0.2). The day-to-day variability in systolic blood pressure was significantly associated with cognitive decline after including home systolic blood pressure in the same model (odds ratio, 1.51; P=0.02), whereas the odds ratio of home systolic blood pressure remained positive, but it was not significant. Home blood pressure measurements can be useful for predicting future cognitive decline because they can provide information not only on blood pressure values but also on day-to-day blood pressure variability. (Hypertension. 2014;63:1333-1338.)

•

Online Data SupplementKey Words: blood pressure ■ cohort studies ■ mild cognitive impairment

Received July 1, 2013; first decision July 15, 2013; revision accepted March 3, 2014.

From the Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics (A.M., T.Hashimoto, H.S.), Department of Preventive Medicine and Epidemiology (M.K., T.Obara), and Department of Community Medical Supports (H.M.), Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization, Department of Planning for Drug Development and Clinical Evaluation (T.Hirose, K.A., K.T., Y.I.), Department of Human Development, Faculty of Education (T.Hosokawa), Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan; Department of Pharmacy (M.S., T.Obara), Medical Information Technology Center (R.I.), Tohoku University Hospital, Sendai, Japan; Department of Hygiene and Public Health, Teikyo University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan (T.Ohkubo); The Faculty of Medical Science and Welfare, Tohoku Bunka Gakuen University, Sendai, Japan (M.H.); Department of Pharmacy, Sendai Open Hospital, Sendai, Japan (T.Hashimoto); Division of Hypertension and Cardiovascular Rehabilitation, Department of Cardiovascular Diseases, Studies Coordinating Centre, University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium (A.Hara, K.A); Early Development and Pathologies, Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Biology, Collège de France, Paris, France (T.Hirose); Department of Career Design, Sendai Seiyo Gakuin College, Sendai, Japan (A.Hosokawa); Department of Social Welfare, Tohoku Fukushi University, Sendai, Japan (K.T.); and Department of Medicine, Ohasama Hospital, Iwate, Japan (H.H.).

*These authors contributed equally to this work.

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at http://hyper.ahajournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA. 113.01819/-/DC1.

Correspondence to Takayoshi Ohkubo, Department of Hygiene and Public Health, Teikyo University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan. E-mail tohkubo@mail.tains.tohoku.ac.jp

Day-to-Day Variability in Home Blood Pressure

Is Associated With Cognitive Decline

The Ohasama Study

Akihiro Matsumoto,* Michihiro Satoh,* Masahiro Kikuya, Takayoshi Ohkubo, Mikio Hirano,

Ryusuke Inoue, Takanao Hashimoto, Azusa Hara, Takuo Hirose, Taku Obara, Hirohito Metoki,

Kei Asayama, Aya Hosokawa, Kazuhito Totsune, Haruhisa Hoshi, Toru Hosokawa, Hiroshi Sato,

Yutaka Imai

© 2014 American Heart Association, Inc.

provided.7 Thus, it can be hypothesized that home BP can bet-ter predict future cognitive decline than conventional BP.

One of the clinically significant aspects of home BP measure-ments is produced by the multiple BP measuremeasure-ments.6 These multiple home BP measurements can also produce day-to-day BP variability that is calculated from the SD of home BP. Our previous studies demonstrated that high day-to-day BP vari-ability was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality, independent of home BP values, and other risk fac-tors.8,9 However, no studies have investigated the associations of day-to-day BP variability with cognitive impairment.

The objectives of this prospective study were to examine and to confirm the stronger predictive power of home BP val-ues for cognitive decline than conventional BP and to com-pare the predictive power of the averaged home BP and the day-to-day home BP variability for cognitive decline.

Methods

Design

This report was part of the Ohasama study, a community-based BP measurement project ongoing since 1987. Socioeconomic and demo-graphic characteristics of this region and details of the study have been described previously.5,6

Study Population

Of the remaining 2400 eligible individuals, 1436 participated in the baseline examination, and 1396 gave informed consent for follow-up analyses. Of these, the total number of participants included in the present analyses was 485 without cognitive decline (defined as a baseline Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score, <24).10,11

A comparison of the characteristics of the excluded participants and the 485 participants who remained in this follow-up study is shown in Table S1 in the online-only Data Supplement.

BP Measurement

Participants were asked to measure BP and heart rate once every morn-ing for a period of 4 weeks usmorn-ing an oscillometric device (HEM 701C or 747IC-N; Omron Healthcare Co Ltd, Kyoto, Japan).12,13 The value

and variability of home BP were calculated as the average and within-participant SD of the measurements, respectively.8 Conventional BP

was measured twice consecutively by well-trained physicians or nurses in the sitting position, after a minimum 2-minute interval of rest using an automatic device (HEM 907; Omron Healthcare Co Ltd). The mean of the 2 readings was defined as the conventional BP.12 The details of

BP measurement are described in the online-only Data Supplement.

Assessment of Cognitive Function Outcome

Cognitive decline was defined as an MMSE score of <24 at follow-up.10,11 The outcome of this study was defined as new onset

of cognitive decline at follow-up examination. The details of MMSE measurements are described in the online-only Data Supplement.

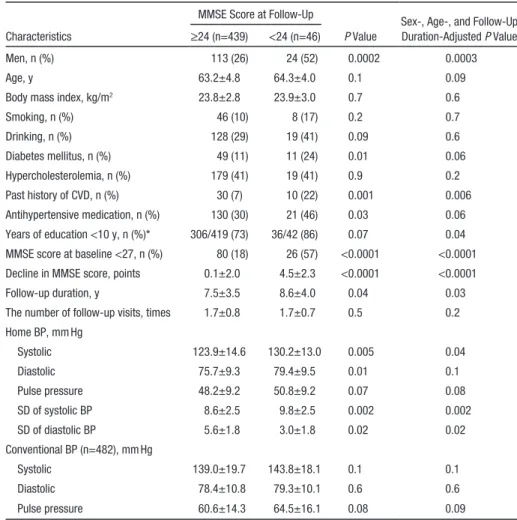

Table 1. Participants’ Characteristics

MMSE Score at Follow-Up

P Value

Sex-, Age-, and Follow-Up Duration-Adjusted P Value

Characteristics ≥24 (n=439) <24 (n=46)

Men, n (%) 113 (26) 24 (52) 0.0002 0.0003

Age, y 63.2±4.8 64.3±4.0 0.1 0.09

Body mass index, kg/m2 23.8±2.8 23.9±3.0 0.7 0.6

Smoking, n (%) 46 (10) 8 (17) 0.2 0.7 Drinking, n (%) 128 (29) 19 (41) 0.09 0.6 Diabetes mellitus, n (%) 49 (11) 11 (24) 0.01 0.06 Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) 179 (41) 19 (41) 0.9 0.2 Past history of CVD, n (%) 30 (7) 10 (22) 0.001 0.006 Antihypertensive medication, n (%) 130 (30) 21 (46) 0.03 0.06 Years of education <10 y, n (%)* 306/419 (73) 36/42 (86) 0.07 0.04

MMSE score at baseline <27, n (%) 80 (18) 26 (57) <0.0001 <0.0001

Decline in MMSE score, points 0.1±2.0 4.5±2.3 <0.0001 <0.0001

Follow-up duration, y 7.5±3.5 8.6±4.0 0.04 0.03

The number of follow-up visits, times 1.7±0.8 1.7±0.7 0.5 0.2

Home BP, mm Hg Systolic 123.9±14.6 130.2±13.0 0.005 0.04 Diastolic 75.7±9.3 79.4±9.5 0.01 0.1 Pulse pressure 48.2±9.2 50.8±9.2 0.07 0.08 SD of systolic BP 8.6±2.5 9.8±2.5 0.002 0.002 SD of diastolic BP 5.6±1.8 3.0±1.8 0.02 0.02 Conventional BP (n=482), mm Hg Systolic 139.0±19.7 143.8±18.1 0.1 0.1 Diastolic 78.4±10.8 79.3±10.1 0.6 0.6 Pulse pressure 60.6±14.3 64.5±16.1 0.08 0.09

Men were only adjusted by age and follow-up duration. Age was only adjusted by sex and follow-up duration. Follow-up duration was only adjusted by sex and age. BP indicates blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; and MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

Physical and Biochemical Examinations

The methods for physical and biochemical examinations in the pres-ent study are described in the online-only Data Supplempres-ent.

Statistical Analysis

The analyses of the data in the present study are described in the online-only Data Supplement. Because several previous studies reported that treatment with antihypertensive medication could affect the predictive power of BPs for prognosis,14,15 participants were

divided into 2 groups according to the use of antihypertensive medi-cation. SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Participants and Characteristics

The participants’ characteristics according to cognitive func-tion at follow-up are shown in Table 1. The proporfunc-tion of men, history of cardiovascular disease, low level of education, duration of follow-up, prevalence of a baseline MMSE score <27, home BP values, and SDs of home BP were significantly higher in participants with cognitive decline than in those without cognitive decline (Table 1).

Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis

After a median follow-up of 7.8 years, 46 (9.5%) participants showed cognitive decline. The risk for cognitive decline was significantly increased across the tertiles of home systolic BP values (trend P=0.04) and those of SD of home systolic BP (trend P=0.046) after adjustments for possible confound-ing factors (Figure 1). There were no significant associations between tertiles of conventional BP values and cognitive decline (odds ratio [95% confidence intervals] per tertile: 1.0 [ref], 2.24 [0.88–5.73], and 2.25 [0.87–5.81]; P≥0.09 for sys-tolic BP, and 1.0 [ref], 1.14 [0.46–2.83], and 1.73 [0.75–3.96];

P≥0.2 for diastolic BP).

Next, home or conventional systolic BP values and SDs of home systolic BP were analyzed as continuous vari-ables (Figure S1). Each 1-SD increase in the home systolic BP value showed a significant association with cognitive decline (odds ratio, 1.48; P=0.03). However, the conven-tional systolic BP value was not significantly associated with cognitive decline (P=0.2). Each 1-SD increase in SD of home systolic BP was significantly associated with cog-nitive decline, after including the averaged levels of home systolic BP in the same model (odds ratio, 1.51; P=0.02). Then, a positive association between the home systolic BP value and cognitive decline remained although it was weak-ened to a nonsignificant level (odds ratio [95% confidence interval], 1.30 [0.90–1.88]; P=0.2).

Stratified analyses according to the use of antihyperten-sive medication were then performed (Figure S1). A high home systolic BP value and a high conventional BP value were significantly associated with cognitive decline only in participants on no antihypertensive treatment (P for inter-action, 0.01 and 0.1, respectively) although the odds ratio per 1-SD increase in the conventional systolic BP value was lower than that of the home systolic BP value (1.77 [1.08– 2.89] versus 2.80 [1.55–5.07]; P≤0.02; Figure S1). No sig-nificant interaction between the SD of home systolic BP and antihypertensive medication on cognitive decline was

observed (P for interaction, 0.6; Figure S1). The patients’ characteristics according to use of antihypertensive drugs are shown in Table S2. Among the 334 on and the 151 not on antihypertensive treatment, 51 (15.3%) and 73 (48.3%), respectively, had home BPs ≥135/85 mm Hg. When the 283 untreated normotensives (home BPs, <135/85 mm Hg) were used as the reference, untreated hypertensives (home BPs, ≥135/85 mm Hg) and treated hypertensives had significantly higher risks for cognitive decline (Table S2).

When we divided the 485 study participants into 4 groups according to the medians of the home systolic BP values (124.7 mm Hg) and of the SD of the home systolic BP (8.55 mm Hg), the group with a higher SD of the home systolic BP (≥124.7 mm Hg) with a higher home systolic BP value (≥8.55 mm Hg) had the greatest risk for cognitive decline (Figure 2).

When all of the analyses were repeated using the dia-stolic BP value, similar trends, although not significant, were observed (Figure 1; Figures S2 and S3). Similar results were obtained when home BP values were defined as the mean of 2 measurements obtained from the initial 2 days (Table 2). When cognitive decline was defined as MMSE scores of <23 or <25, similar tendencies were also observed (Tables S3 and S4).

Home BP values (or initial 2 days’ home BP) and conven-tional BP values were used in the same model. In partici-pants on no antihypertensive treatment, only home BP values were significantly associated with cognitive decline (Tables S5 and S6).

For the sensitivity analyses, further adjustments were made for home pulse pressure, body mass index, total cholesterol levels, smoking status, drinking status, diabetes mellitus, the

0 1 2 3 <71.9 71.9-79.3 >79.3 0 1 2 3 <4.7 4.7-6.0 >6.0 re f (0.4 4-2.84 ) (0.8 5-5.04 )

Home diastolic BP value, mmHg 1.12 2.07 Trend P= 0.09 re f (0.7 3-4.90 ) (0.87-5.43 ) SD of home diastolic BP, mmHg 1.89 Trend P= 0.1 0 1 2 3 <117.6 117.6-129.5 >129.5 0 1 2 3 <7.3 7.3-9.6 >9.6 re f (0.81-5.67 ) (1.04-6.83)*

Home systolic BP value, mmHg

Odds ratios (95% C.I.) 2.14 2.67 Trend P= 0.046 re f (0.78-5.32 ) (1.06-6.95)* SD of home systolic BP, mmHg Odds ratios (95% C.I.) 2.04 2.72 Trend P= 0.04 2.17

Figure 1. Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals [CI]) for cognitive decline among the tertiles of home blood pressure (BP) values (top) and the tertiles of the SD of the home BPs (bottom), after adjusting for sex, age, history of cardiovascular disease, low level of education, baseline Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score <27, and follow-up duration. In the analysis of the SDs of the home BP measurements, further adjustments were made for the home systolic BP value. Cognitive decline was defined as MMSE score <24 at follow-up. P<0.05 vs reference (ref).

use of antihypertensive drugs, and the number of follow-up visits. Even after applying these adjustments, the significant association of the SD of the home systolic BP with cognitive decline was unchanged (odds ratio, ≥1.47; P≤0.03), whereas the significant association of the home systolic BP with cogni-tive decline remained only in participants not on antihyperten-sive treatment (odds ratio, ≥2.60; P≤0.002).

Discussion

There are 2 key novel findings of the present study. First, in line with the previous studies demonstrating the clear asso-ciation of home BP with cardiovascular disease6 or target

organ damage,5 the home BP values were more strongly associated with cognitive decline than conventional BP val-ues. Second, this is the first study demonstrating a significant association between day-to-day BP variability, defined as the SD of home measurements and cognitive decline indepen-dent of home systolic BP.

Previous longitudinal studies reported significant associa-tions between elevated conventional BP and an increased risk for cognitive decline.1 However, home BP values were more strongly associated with cognitive decline than conventional BP values. Consistent with the results of previous studies,14,15 the association of BP values with cognitive decline was strengthened for participants on no antihypertensive treatment. We previously reported that the predictive value of the initial 2 days’ home BP for stroke was greater than that of 2 office BP readings.6 Consistent with this, the results based on the initial 2 days’ home BP (Table 2) suggest that the home BP values might more strongly predict future cognitive decline than con-ventional BP, regardless of the number of measurements. The stronger association between the home BP value and cogni-tive decline than between the conventional BP value and cog-nitive decline can be explained by the fact that out-of-office BP measurements provide more reproducible information on BP,16 eliminate the white-coat effect,4 have more prognostic significance,6 and are more indicative of target organ damage than conventional BP measurements.5 Recent epidemiological studies have reported the strong prognostic value of home BP when compared with conventional BP.9,17,18 The conventional BP values were higher than the home BP values, suggesting the possibility that conventional BP included the white-coat effect in the present study (Table 1). This is consistent with previous studies.18 However, the relationships of the 2 mea-surements with cognitive decline do not resolve the issue of day-to-day BP variability in terms of white-coat hypertension because the conventional BP measurements cannot provide day-to-day BP variability.

Table 2. The Associations of the Initial 2-Day Home and Conventional BPs With Cognitive Decline Independent Variables

(Per 1 SD Increase) Subgroups

Odds Ratio (95% Confidence

Interval) for Cognitive Decline P Value

Interaction for P Value (BP×Antihypertensive Treatment)

Home systolic BP All participants 1.47 (1.04–2.07) 0.03 …

Treated 0.93 (0.51–1.71) 0.8 0.1

Untreated 2.12 (1.27–3.54) 0.004

Home diastolic BP All participants 1.55 (1.11–2.17) 0.01 …

Treated 1.04 (0.59–1.85) 0.9 0.01

Untreated 2.95 (1.62–5.36) 0.0004

Conventional systolic BP All participants 1.21 (0.88–1.67) 0.2 …

Treated 0.82 (0.50–1.34) 0.4 0.09

Untreated 1.75 (1.07–2.84) 0.02

Conventional diastolic BP All participants 1.09 (0.78–1.52) 0.6 …

Treated 0.93 (0.55–1.58) 0.8 0.5

Untreated 1.28 (0.79–2.08) 0.3

Home blood pressure (BP) values were based on 2 measurements obtained from initial 2 days. We analyzed in 491 participants who measured ≥2 morning home BP recordings. Overall, 23 and 25 participants had cognitive decline among subgroups treated (n=155) and untreated (n=336) with antihypertensive medication, respectively. Odds ratios were adjusted for sex, age, history of cardiovascular disease, low level of education, baseline Mini-Mental State Examination score <27, and follow-up duration. In the analysis of the SD of the home systolic BP measurement, we further adjusted for home systolic BP value.

23/158 6.40* 10/85 4.89* Odds ratios (95% C.I.) (2.11-19.4) (0.80-9.76) (1.44-16.7) ≥8.6 <8.6 ≥124.7 <124.7 ref 8/85 2.79 5/157 SD of home systolic BP, mmHg Home systolic BP, mmHg 1 0 2 3 4 5 6 7

Figure 2. Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals [CI]) for cognitive decline associated with the combination of home systolic blood pressure (BP) value and the SD of the home systolic BP, after adjusting for sex, age, history of cardiovascular disease, low level of education, baseline Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score <27, and follow-up duration. The incidence/number of subjects in each group is shown on each bar. A higher home systolic BP value is defined as ≥124.7 mm Hg (dichotomized at upper quartiles). A higher SD of the home BP is defined as ≥8.6 mm Hg

(dichotomized at upper quartiles). Cognitive decline is defined as an MMSE score <24 at follow-up. *P<0.05 vs reference (ref).

The present study demonstrated for the first time that day-to-day BP variability may predict cognitive decline in a general population. The visit-to-visit variability in office BPs was recently reported to be associated with impaired cognitive function.19 This report supports the present results. However, their study was conducted in a special patient population at high risk of cardiovascular disease, and the visit-to-visit BP variability was calculated from multiple office BPs measured every 3 months during a relatively short-term follow-up of 3.2 years.19 Furthermore, it is difficult to evaluate visit-to-visit BP variability in normotensives or untreated hypertensives who do not regularly go to a hospital. One cross-sectional study demonstrated the association of elevated short-term BP vari-ability with cognitive impairment in 202 patients aged ≥60 years with stable treatments for various chronic diseases.20 It has been reported that day-to-day BP variability and short-term BP variability can be related to autonomic dys-function,21 carotid intima-media thickness,22 and cardiovascu-lar mortality.8,23 Orthostatic hypotension, which is one of the symptoms of autonomic dysfunction, can cause cerebral isch-emia and has been reported to be associated with dementia.24 Several studies have reported that atherosclerosis can also be a factor related to cognitive decline or dementia.25,26 From these previous studies,21,22,25,26 the association of day-to-day BP variability with cognitive decline may be mediated partly by autonomic dysfunction and arterial stiffness although home pulse pressure was not associated with cognitive decline. Previously, we demonstrated the significant association of high day-to-day BP variability with the risk of cardiovascu-lar mortality in a general population.8 Therefore, measuring not only the BP value itself but also day-to-day BP variability may provide important information for detecting early stages of dementia and cardiovascular disease.

This study had several limitations. First, study participants included predominantly middle-aged and elderly women and were selected only from volunteers who could participate in health check-ups during the daytime. Furthermore, the num-bers of participants and cognitive decline events were small. These might, to some extent, limit the external validity of the findings. Second, the follow-up participants (n=485) were significantly younger, had lower home systolic BP values, included a higher proportion of participants on no antihyper-tensive medication, and had a higher level of education and lower mortality after the last examination than the excluded participants (n=617; Table S1). Thus, participants in the follow-up examination of the present study represent a rela-tively healthy group. This might have led to an underestima-tion of the true relaunderestima-tionships between BP values or day-to-day BP variability and cognitive decline. Third, marked differ-ences exist in the epidemiology of dementia between Japan and the United States or European countries. However, in rela-tion to the significant prognostic power of day-to-day vari-ability, similar findings to our previous study23 were obtained in the Finn-Home study, in which the subjects were Finnish.27 Thus, it is possible that the association of day-to-day BP vari-ability with cognitive decline in Japanese may also not differ from that in whites. Fourth, data on depression status, using the Sheehan Disability Scale, were collected in only 32 study participants, making it impossible to take into account the

effect of depression. Finally, conventional BP was defined as 2 measurements on a single occasion in the present study. The American Heart Association and other guidelines12,28 rec-ommend taking BP assessments on ≥2 separate occasions to diagnose a patient with hypertension. Furthermore, it has been reported that future cognitive decline is strongly predicted by office BP measured on multiple occasions.1–3 Thus, the predic-tive power of conventional BP for cognipredic-tive decline would be enhanced by multiple measurements. Further studies based on multiple BP measurements in an office are needed to eluci-date the stronger predictive power of home BP for cognitive decline when compared with that of BP measured in an office. Then, automated office BP measurement, which is recom-mended by the Canadian guideline, may be useful to assess multiple BP values in an office.29

Perspective

The present study provides the first prospective evidence that, in a general population, home BP values and day-to-day home BP variability may predict cognitive decline. Home BP measurement has already been recommended for manage-ment of hypertension by guidelines,12,16 including the 2013 European Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Cardiology guideline.28 In addition, the present study sug-gests that BP values and day-to-day BP variability derived from self-measurement at home may also be a simple method of providing useful clinical information for assessing cogni-tive decline.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the residents of the town of Ohasama, all relat-ed investigators and study staff, and staff members of the Ohasama Town Government, Ohasama Hospital, and Iwate Prefectural Stroke Registry for their valuable support for this project. A. Matsumoto and M. Satoh wrote the first draft of this article. All authors conducted the Ohasama Study and commented on the article.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by grants for Scientific Research (23249036, 23390171, 24591060, 24390084, 24591060, 24790654, 25461205, 25461083, and 25860156) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan; Grants-in-Aid for Japan Society for the Promotion of Science fellows (25.9328 and 25.7756); a Health Labor Sciences Research Grant (H23-Junkankitou [Seishuu]-Ippan-005) from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan; the Japan Arteriosclerosis Prevention Fund; a grant from the Daiwa Securities Health Foundation; and Research Funding for Longevity Sciences (23–32) from the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology.

Disclosures

None.References

1. Elias MF, Goodell AL, Dore GA. Hypertension and cognitive functioning: a perspective in historical context. Hypertension. 2012;60:260–268. 2. Elias MF, Robbins MA, Elias PK, Streeten DH. A longitudinal study

of blood pressure in relation to performance on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. Health Psychol. 1998;17:486–493.

3. Elias MF, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Cobb J, White LR. Untreated blood pressure level is inversely related to cognitive functioning: the Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:353–364.

4. Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, et al.; ESH Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring. European Society of Hypertension guidelines for

blood pressure monitoring at home: a summary report of the Second International Consensus Conference on Home Blood Pressure Monitoring.

J Hypertens. 2008;26:1505–1526.

5. Hara A, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, et al. Detection of carotid atherosclerosis in individuals with masked hypertension and white-coat hypertension by self-measured blood pressure at home: the Ohasama study. J Hypertens. 2007;25:321–327.

6. Ohkubo T, Asayama K, Kikuya M, Metoki H, Hoshi H, Hashimoto J, Totsune K, Satoh H, Imai Y; Ohasama Study. How many times should blood pressure be measured at home for better prediction of stroke risk? Ten-year follow-up results from the Ohasama study. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1099–1104. 7. Asayama K, Ohkubo T, Metoki H, Obara T, Inoue R, Kikuya M, Thijs

L, Staessen JA, Imai Y; Hypertension Objective Treatment Based on Measurement by Electrical Devices of Blood Pressure (HOMED-BP). Cardiovascular outcomes in the first trial of antihypertensive therapy guided by self-measured home blood pressure. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:1102–1110. 8. Kikuya M, Ohkubo T, Metoki H, Asayama K, Hara A, Obara T, Inoue

R, Hoshi H, Hashimoto J, Totsune K, Satoh H, Imai Y. Day-by-day vari-ability of blood pressure and heart rate at home as a novel predictor of prognosis: the Ohasama study. Hypertension. 2008;52:1045–1050. 9. Asayama K, Kikuya M, Schutte R, Thijs L, Hosaka M, Satoh M, Hara

A, Obara T, Inoue R, Metoki H, Hirose T, Ohkubo T, Staessen JA, Imai Y. Home blood pressure variability as cardiovascular risk factor in the population of Ohasama. Hypertension. 2013;61:61–69.

10. Mori E, Mitani Y, Yamadori A. Usefulness of a Japanese version of the Mini-Mental State Test in neurological patients. Jpn J Neuropsychol. 1985;1:82–90.

11. Folstein M, Anthony JC, Parhad I, Duffy B, Gruenberg EM. The meaning of cognitive impairment in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1985;33:228–235.

12. Ogihara T, Kikuchi K, Matsuoka H, et al.; Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2009). Hypertens Res. 2009;32:3–107. 13. Imai Y, Satoh H, Nagai K, Sakuma M, Sakuma H, Minami N, Munakata M, Hashimoto J, Yamagishi T, Watanabe N, Yabe T, Nishiyama A, Nakatsuka H, Koyama H, Abe K. Characteristics of a community-based distribu-tion of home blood pressure in Ohasama in northern Japan. J Hypertens. 1993;11:1441–1449.

14. Korf ES, White LR, Scheltens P, Launer LJ. Midlife blood pressure and the risk of hippocampal atrophy: the Honolulu Asia Aging Study.

Hypertension. 2004;44:29–34.

15. den Heijer T, Launer LJ, Prins ND, van Dijk EJ, Vermeer SE, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Association between blood pressure, white matter lesions, and atrophy of the medial temporal lobe. Neurology. 2005;64:263–267.

16. Imai Y, Kario K, Shimada K, Kawano Y, Hasebe N, Matsuura H, Tsuchihashi T, Ohkubo T, Kuwajima I, Miyakawa M; Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee for Guidelines for Self-monitoring of Blood Pressure at Home. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for

Self-monitoring of Blood Pressure at Home (Second Edition). Hypertens

Res. 2012;35:777–795.

17. Hänninen MR, Niiranen TJ, Puukka PJ, Johansson J, Jula AM. Prognostic significance of masked and white-coat hypertension in the general popula-tion: the Finn-Home Study. J Hypertens. 2012;30:705–712.

18. Niiranen TJ, Asayama K, Thijs L, Johansson JK, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Boggia J, Hozawa A, Sandoya E, Stergiou GS, Tsuji I, Jula AM, Imai Y, Staessen JA; International Database of Home Blood Pressure in Relation to Cardiovascular Outcome Investigators. Outcome-driven thresholds for home blood pressure measurement: international database of home blood pressure in relation to cardiovascular outcome. Hypertension. 2013;61:27–34. 19. Sabayan B, Wijsman LW, Foster-Dingley JC, Stott DJ, Ford I, Buckley

BM, Sattar N, Jukema JW, van Osch MJ, van der Grond J, van Buchem MA, Westendorp RG, de Craen AJ, Mooijaart SP. Association of visit-to-visit variability in blood pressure with cognitive function in old age: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2013;347:f4600.

20. Sakakura K, Ishikawa J, Okuno M, Shimada K, Kario K. Exaggerated ambulatory blood pressure variability is associated with cognitive dys-function in the very elderly and quality of life in the younger elderly. Am J

Hypertens. 2007;20:720–727.

21. Zhang Y, Agnoletti D, Blacher J, Safar ME. Blood pressure variability in relation to autonomic nervous system dysregulation: the X-CELLENT study. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:399–403.

22. Tatasciore A, Renda G, Zimarino M, Soccio M, Bilo G, Parati G, Schillaci G, De Caterina R. Awake systolic blood pressure variability correlates with tar-get-organ damage in hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 2007;50:325–332. 23. Kikuya M, Hozawa A, Ohokubo T, Tsuji I, Michimata M, Matsubara M,

Ota M, Nagai K, Araki T, Satoh H, Ito S, Hisamichi S, Imai Y. Prognostic significance of blood pressure and heart rate variabilities: the Ohasama study. Hypertension. 2000;36:901–906.

24. Allan LM, Ballard CG, Allen J, Murray A, Davidson AW, McKeith IG, Kenny RA. Autonomic dysfunction in dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg

Psychiatry. 2007;78:671–677.

25. Wendell CR, Zonderman AB, Metter EJ, Najjar SS, Waldstein SR. Carotid intimal medial thickness predicts cognitive decline among adults without clinical vascular disease. Stroke. 2009;40:3180–3185.

26. van Oijen M, de Jong FJ, Witteman JC, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Atherosclerosis and risk for dementia. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:403–410.

27. Johansson JK, Niiranen TJ, Puukka PJ, Jula AM. Prognostic value of the variability in home-measured blood pressure and heart rate: the Finn-Home Study. Hypertension. 2012;59:212–218.

28. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guide-lines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).

Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2159–2219.

29. Myers MG, Godwin M. Automated office blood pressure. Can J Cardiol. 2012;28:341–346.

What Is New?

•

This is the first prospective study to demonstrate that higher home blood pressure (BP) values and higher SD of home systolic BP were signifi-cantly associated with an increased risk for cognitive decline in a general population.What Is Relevant?

•

Home BP values and day-to-day home BP variability can be important predictors for cognitive decline in a general population.Summary

A higher home BP value with a higher SD of home BP was associ-ated with future cognitive decline. Thus, measuring not only the home BP value but also day-to-day BP variability may provide im-portant information for detecting early stages of cognitive decline.

![Figure 1. Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals [CI]) for cognitive decline among the tertiles of home blood pressure (BP) values (top) and the tertiles of the SD of the home BPs (bottom), after adjusting for sex, age, history of cardiovascular disease,](https://thumb-us.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_us/9952644.2889919/3.877.473.790.100.440/confidence-intervals-cognitive-tertiles-pressure-tertiles-adjusting-cardiovascular.webp)

![Figure 2. Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals [CI]) for cognitive decline associated with the combination of home systolic blood pressure (BP) value and the SD of the home systolic BP, after adjusting for sex, age, history of cardiovascular disease, l](https://thumb-us.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_us/9952644.2889919/4.877.153.725.761.1039/confidence-intervals-cognitive-associated-combination-systolic-adjusting-cardiovascular.webp)