110

Business Process Management in Organization:

A Critical Success Factor

∗

Euphrasia S. Suhendra, Teddy Oswari

Gunadarma University, Depok, Indonesia

The principle aim of this paper is to investigate the relationship between business process management (BPM) and business performance, and the effectiveness of business process management in an organization. This study has been undertaken with the specific objectives of understanding the difference between business process reengineering (BPR) and business process management, whether business process management can be successfully implemented in organizational environment and if so, how to implement and apply business process management in industry in order to achieve business success. Industry is seeking to improve operational efficiencies, meet customer demands more quickly and leverage existing technology investments. Business process management has the potential to deliver the benefits of process efficiency throughout all stages of a business process and to all areas of the organization. Business process management focuses on business practices and management disciplines as the underlying enablers of a process-centric organization, the exploratory study was conducted to identify the process performance and readiness of organization to implement business process management.

Keywords: management, business process, organization

Over the last decade, the concept of “business process” has entered the business mainstream. Leading organizations in virtually every industry have discovered that by harnessing, managing and redesigning the organization’s business processes, organizations can achieve spectacular improvements in business performance and customer service. In a business world that promises to continue to be characterized by slow growth, intense global competition, worldwide overcapacity and powerful customers, process management offers organizations the opportunity to outperform competitors and take market share away from competitors. Smith and Finger (2003, p. 2) pointed out that while the vision of process management is not new, existing theories and implementations have not been able to cope with the reality of business process management. At first, the theory of management processes implicit in work practices dominated within business process management. In the past decade or so, processes were manually re-engineered. Harmon (2003, p. 37) added that the business environment has changed and organizations that have implemented process projects have learned important lessons.

The lessons learnt were looked how to relate specific improvement projects to corporate goals. Many of

∗

Acknowledgement: To Prof. E. S. Margianti and Prof. H. S. Suryadi, thanks for their support and encouragement given for this study; and to Mrs. E. Susy Suhendra, thanks for her assistance and support and making this a truly enriching experience.

Corresponding author: Euphrasia S. Suhendra, professor, Faculty of Economics, Gunadarma University; research fields: management, productivity, project management. E-mail: susys@staff.gunadarma.ac.id.

Teddy Oswari, professor, Faculty of Economics, Gunadarma University; research fields: banking management, financial management, risk management theory, project management theory.

the projects, undertaken by organizations in the mid-1990s, developed process paths and solved business problems that were not strategically important to the organization. The implementation of redesigned business processes maximized the effect on business process but did not take into consideration the broader reasoning and context of redesign. During the late 1990s, individual processes were aligned to organizational strategies and goals, and focused on the problems of implementing reengineered processes. According to Rosemann and de Bruin (2005, p. 10), BPM consolidates business objectives and methodologies, and a number of approaches have been proposed, including business process reengineering, process innovation, business process modeling and business process automation/workflow management.

Business process management is widely recognized as a foundation for contemporary management approaches, as it goes via the analysis of business processes to the roots of an organization. Smith and Finger (2003, pp. 10-18) indicated that the change is currently the primary design goal, because in the world of business process management, the ability to change is far more prized than the ability to create in the first place. It is through business process management that entire value chains can be monitored, continuously improved and optimized. However, the question remains, can business process management show a change to increasing achievement in company?

A process, according to Davenport (1993a, p. 3), is “a structured, measured set of activities designed to produce a specified output for a particular customer or market. It implies a strong emphasis on how work is done within an organization”. Balle defined a process as “a sequence of dependent events. In practice, almost everything which involves time can be called a process under some form or other” (Balle, 1995, p. 167).

Davenport and Short (1990, p. 15) defined business process as: “a set of logically related tasks performed to achieve a defined business outcome”. Davenport and Short (1990, p. 20) subsumed business processes under three dimensions: (1) Entities: Processes take place between organizational entities. Processes could be inter-organizational, inter-functional or inter-personal; (2) objects: Processes result in manipulation of objects. These objects could be physical or informational; (3) activities: Processes could involve two types of activities: managerial (e.g., develop a budget) and operational (e.g., fill a customer order).

Davenport and Short (1990, p. 16) viewed processes as having two important characteristics: Processes have customers (internal or external), processes cross organizational boundaries (processes occur across or between organizational subunits). Processes are generally identified in terms of beginning and end points, interfaces and organization units involved, particularly the customer unit. High impact processes should have process owners. Examples of processes include: developing a new product; ordering goods from a supplier; creating a marketing plan; processing and paying an insurance claim. Hammer (2001, p. 12) stated that processes are what create the results that a organization delivers to its customers. Process is a technical term with a precise definition: “… an organized group of related activities that together create a result of value to customers. Processes are not random or ad hoc, processes are related and organized. All activities in a process must work together toward a common goal and processes are not ends in themselves, processes have a purpose that transcends and shapes all processes constituent activities”.

Hammer and Champy (1993, pp. 11-24) stated the following reasons:

(1) Processes associated with twenty-first century products and services are far more complicated than manufacturing pins in a factory, and require many more tasks. Managing and coordinating these tasks as prescribed by the division of labor model are very difficult;

and management. Customers’ needs become too abstract and unknown to managers;

(3) As task decomposition and coordination becomes an intricate process, adapting it to changes in the environment becomes more difficult. This presents the concept of redesigning business processes on a clean slate, with the aim of evolving and organization consisting of a mesh of narrow, task-oriented jobs into one comprising multi-dimensional jobs where employees are expected to think, take responsibility, and act.

Hammer and Champy’s original seven best practices and principles (1993, p. 110) are: (1) Organize around results and outcomes, not tasks (several jobs are combined into one); (2) have the users of the process output, perform the process (employees make decisions); (3) subsume information-processing work into the real work that produces the information (the steps of the process are performed in a natural order); (4) treat geographically dispersed resources as though the resources were centralized (hybrid centralized/decentralized operations prevail); (5) link parallel activities instead of integrating the results of these activities (reconciliation is minimized); (6) put the decision point where the work is performed, and build control into the process (checks and controls are reduced); (7) capture information once and at the source (work is performed where it makes most sense). Furthermore, Smith and Finger (2003, p. 15) stated that the term “process management” has resonated most strongly in the consciousness of the business world ever since the advent of business process reengineering. A completely new approach to process design and implementation has therefore emerged. It provides for the creation of a single definition of a business process from which different views of that process can be rendered. This unified representation means that different people with different skills can each view and manipulate the same process. Business process management is not a point solution or a single product, it is a mandatory business capability that allows the business to take control of its current and future process needs. End-to-end process visibility, agility and accountability are now the keys to business innovation.

The general objective of the paper is to investigate the relationship between business process management and business performance, and investigate the effectiveness of business process management in industry. In defining the limits of the study, the literature review conducted identified the study areas to be addressed. The literature review led to the development of the following specific research objectives.

Business Process Reengineering and Business Process Management

Business process reengineering builds on total quality management (TQM) and therefore business process reengineering is further defined to illustrate the key components of reengineering, fundamental thinking, radical redesign, processes and dramatic improvements. The definition of business process reengineering and its components are not adequate to fully understand business process reengineering, and therefore the methodologies in business process reengineering are included to provide a greater insight into the concept. The expectations of business process reengineering exceeded what business process reengineering in reality delivered to organizations and this provided an opportunity to further evolve business process reengineering.

A total quality organization implementing the TQM programmed is an organization that operates with certain underlying core values and concepts, including customer driven quality, involved and active leadership, continuous improvement and learning, employee participation and development, fast response, design quality and loss prevention, a long range view, management by fact, partnership development, corporate responsibility and citizenship, and the organization is result-oriented.

BPR is about establishing and defining customer requirements and then aligning horizontal processes, that is, across departments and/or functions, to meet those needs. BPR has the potential to remove all wasted effort

in the workplace, thus allowing clear roles and responsibilities to be defined. The result is an optimized process that promotes an environment of continuous improvement through a dedicated and empowered workforce (Mckay & Radnor, 1998, p. 926).

Hammer and Champy (1993, p. 32) have defined reengineering as “the fundamental rethinking and radical redesign of business process to achieve dramatic improvement in critical contemporary measures of performance such as cost, quality, service, and speed”.

PR advocates that enterprises go back to the basics and re-examine the enterprise’s very roots. BPR does not consider small improvements in business; rather it aims at total reinvention (Muthu, Whitman, & Cheraghi, 1999, p. 1). During the last decade, many authors have produced ideas regarding what BPR really is, and there are many authors with different BPR definitions (Choi & Chan, 1997, p. 51). The various authors’ views and beliefs correspond with the definition of Hammer and Champy (1993, p. 32). Nevertheless, the idea of BPR began to evolve where many theoretical propositions underlying BPR surfaced (Khong & Richardson, 2003, p. 56). Table 1 shows some of the developments that BPR has undergone. Although the theoretical propositions differ, similarities are present (Khong & Richardson, 2003, p. 56).

Table 1

Approaches or Perspectives to BPR and Theoretical Basis of BPR

Authors Approaches of perspectives to BPR Theoretical basis of BPR Davenport and Short Operational An extension of industrial engineering

Davenport Strategic and operational Combination of industrial engineering, quality movement and technological innovation

Harrington Strategic and operational Quality movement

Hammer and Champy Strategic, organizational and operational Change management, strategic IT and process innovation Rigby Organizational Scientific management and value analysis

Zairi and Sinclair Strategic, organizational and operationalStrategic management, strategic IT, industrial engineering, change management, process innovation and management Jarrar and Aspinwall Operational and strategic Change management, human resource management, process

innovation and management

Al-Mashari and Zairi Strategic, organizational and operational

Strategic management, human resource management, change management, quality movement, process innovation and management and strategic IT

Note. Source: Adapted from Davenport & Short, 1990; Davenport, 1993b; Harrington, 1991; Hammer & Champy, 1993; Rigby, 1993; Zairi & Sinclair, 1995; Jarrar & Aspinwall, 1999; Al-Mashari & Zairi, 1999.

A concise discussion of the concepts according to Hammer and Champy (1993, p. 32) of reengineering, fundamental rethinking, radical redesign, process and dramatic improvement will follow.

Methodologies in Business Process Reengineering

BPR may be characterised from the definitions, but the definitions do not include a well-defined methodology to show how to perform the actual BPR effort (Choi & Chan, 1997, p. 43). The methods range from aligning employees possessing certain skills with core competencies within an organisation (Horney & Koonce, 1995, pp. 37-44) to estimating the value of business processes and determining the return on investment for reengineering each process (Housel, Bell, & Kanevsky, 1994, pp. 5-40; Davenport, 1993b; I. Jacobson, Ericcson, & A. Jocabson, 1995; Manganelli, 1993) proposed methodologies for BPR (see Table 2).

Table 2

BPR Methodologies

Davernport proposed the following steps Jacobson et al. intended for BPR The suggested methodology by Manganelli (1) Identify processes for innovation;

(2) Identify change layers; (3) Develop process visions; (4) Understand existing processes; (5) Design and prototype the new process; (6) Identify processes for innovation; (7) Identify change layers;

(8) Develop process visions; (9) Understand existing processes; (10) Design and prototype the new process.

(1) Develop business vision; (2) Understand the existing business; (3) Design the new business; (4) Install the new business.

(1) Preparation: Organize the project team; (2) Identification: Develop a

customer-oriented process model; (3) Vision: Select processes and formulate redesign opportunities;

(4) Solution: Define technical and organization requirements for the new process;

(5) Transformation: Implement the reengineering plan.

Note. Source: Adapted from Davenport, 1993b; Jacobson et al., 1995; Manganelli, 1993.

Critical Success Factors and Failures of Business Process Reengineering

The execution of BPR claims remarkable results on performance improvements and is capable of producing a broad range of results for organizations (Attaran & Wood, 1999, p. 752; Choi & Chan, 1997, p. 43). Several organizations achieved large cost reductions and higher profits, improved quality and productivity, faster response to market, and better customer service (Attaran & Wood, 1999, p. 752). Factors that lead to successful outcomes for reengineering projects include:

(1) Strategic alignment with the organizations strategic direction;

(2) Compelling business case for business change with measurable objectives; (3) Proven methodology;

(4) Effective change management that addresses cultural transformation; (5) Line management ownership and accountability;

(6) Knowledgeable and competent reengineering teams.

Not every BPR project is successful. An estimate, reinforced by Hammer and Champy (1993), indicated that 70 percent of organizations failed to achieve benefit from reengineering efforts. In addition, a survey was performed of the experience of Fortune 500 companies and large British companies with reengineering. The finding was that executives were only partially pleased with the reengineering results (Berman, 1994, p. 22).

Reasons for failure according to Peltu, Clegg and Sell (1996, p. 10) and Choi and Chan (1997, p. 44) are: (1) Unclear concepts—too many terms and definitions as well as the misuse of terms;

(2) Pursuing a restructuring or downsizing strategy rather than a reengineering approach; (3) Lack of well-established methodology—problems with redesigned methods and approaches; (4) Unrealistic expectations;

(5) Misinterpretation of BPR; (6) Skills and resource shortages;

(7) Resistance and lack of top management commitment; (8) Fear of downward decision making authority;

(9) The best people not seconded or dedicated on BPR design teams;

(10) Lack of corporate information systems and inadequate attention to providing appropriate new IT-based business systems;

(11) Incorrect objectives, scope and process selection—reengineering the wrong processes, without sufficient process improvement;

(12) Incapable of recognizing the benefits of BPR.

Expectations of Business Process

According to Hammer and Champy (1993, p. 32), the aim of BPR is to achieve a dramatic improvement in performance. But BPR has failed to deliver the expected results (Harrington, 1991, pp. 69-71). Guidelines for measurement of the degree of dramatic improvement for BPR do not exist. As a result, BPR is incorrectly interpreted as a miracle prescription which can provide a quick-fix solution for all problems (Manganelli, 1993, pp. 7-86). Inflated expectations by top management about the speed, scope or benefits of reengineering exist (Kiely, 1995, p. 15). The unrealistic expectations lead to management disappointment with BPR because of the modest achievement. Although there has been no absolute figure to indicate the success of BPR, a guideline on performance indication is that 30 percent improvement can be a breakthrough in business performance and design (Klien, 1993, pp. 2-40). In order to minimize the chance of process failure owing to inflated expectations, clear process goals and expectations should be set according to specific requirements and conditions. In the progress from BPR to BPM, process goals and expectations should be reviewed and adjusted according to an organizations situation (Choi & Chan, 1997, p. 44). The key elements of BPR have been identified (see Table 3).

Table 3

The Types of Business Processes in an Organization

Finance Human resources Operations

(1) Customer/product profitability; (2) Credit request/authorization; (3) Treasury/cash management; (4) Property tracking/accounting; (5) Internal audit; (6) Collections; (7) Physical inventory; (8) Cheque request processing; (9) Capital expenditures; (10) Asset management.

(1) Time and expense processing; (2) Payroll processing; (3) Performance management; (4) Recruitment; (5) Hiring/orientation; (6) Succession planning; (7) Benefit administration; (8) Performance review. (1) Procurement; (2) Order management; (3) Invoicing; (4) Shipping/integrated logistics; (5) Order fulfillment; (6) Manufacturing; (7) Inventory management; (8) Production scheduling;

(9) Advance planning and scheduling; (10) Demand planning;

(11) Capacity planning; (12) Timekeeping/reporting. Customer relationship management Marketing and sales Specific processes (1) Service agreement management;

(2) Internet customer service; (3) Call centre service;

(4) Problem/resolution management; (5) Customer inquiry;

(6) Sales channel management; (7) Inventory management; (8) Service fulfillment.

(1) Account management; (2) Market research and analysis; (3) Product/brand marketing; (4) Program management; (5) Sales cycle management; (6) Installation management; (7) Sales commission planning; (8) Customer acquisition; (9) Security fulfillment; (10) Sales planning. (1) Commissions processing; (2) Service provisioning; (3) Proposal preparation; (4) Capacity reservation;

(5) Advance planning and scheduling; (6) Product data management; (7) Supply chain planning;

(8) Order management and fulfillment; (9) Returns management.

Note. Source: Adapted from Smith, 2003.

Business Process Management

to increase profitability; BPM emerged out of TQM and BPR (Llewellyn & Armistead, 2000, p. 225) and spans the business and technological gap to create synergy (Gartner, 2003, p. 2; Ultimus, 2003, p. 3). Definitions of BPM range from IT-focused views to BPM as a holistic management practice (Rosemann & de Bruin, 2005, p. 1). The IT-focused definition characterizes BPM as follows:

(1) Harmon (2003) defined BPM from the perspective of business process automation;

(2) BPM has multiple uses, from a simple personal flow to complex system-to-system flows under performance constraints; it is therefore difficult to find a common definition for the technological aspect of BPM (Gartner, 2003, p. 1);

(3) Tibco (2003): “BPM technology is a framework of applications that effectively tracks and orchestrates business process. BPM solutions automatically manage processes, allow manual intervention, extract customer information from a database, add new customer transaction information, generate transactions in multiple related systems, and support straight-though processing without human intervention when needed…”;

(4) According to Sinur and Bell (2003, p. 2), BPM is the general term for the services and tools that support workflow (combination of tasks that define a process), human-to-human flow and related tasks, support for human and application level interaction, system-to-system flow automation and process management, including process analysis, process definition, process execution, process monitoring and administration.

Other researches, such as Zairi and Sinclair (1995, pp. 8-30); Detoro and McCabe (1997, pp. 55-60); Pritchard and Armistead (1999, pp. 10-32), agree stating that BPM entails an holistic management approach: (1) The focus is often on analyzing and improving processes (Zairi & Sinclair, 1995, pp. 8-30);

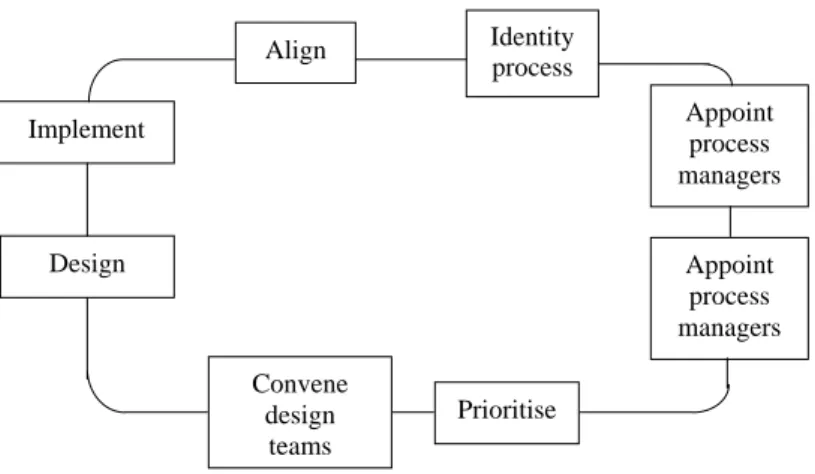

Figure 1. Business process management. Source: Towers, 2004.

(2) A new way of managing an organization, which is different from a functional, hierarchical management approach (Detoro & McCabe, 1997, pp. 55-60; Pritchard & Armistead, 1999, pp. 10-32);

(3) Armistead and Machin (1997, pp. 886-898) stated that BPM is “concerned with how to manage processes on an ongoing basis, and not just with the one-off radical changes associated with BPR...”

(4) Zairi (1997, pp. 64-80) is of the opinion that BPM does not only rely on good systems and structural changes, but even more important, on cultural change. The holistic approach requires alignment to corporate objectives and an employee’s customer focus and involves, besides horizontal focus, strategy, operations, techniques and people. In addition to the need for measurement, improvement and benchmarking and customer focus the need for systematic methodology is stressed;

(5) At the business level, BPM is the management of explicit processes from beginning to end. The processes generally contain a long-running set of business activities for example activities required to underwrite policy or deliver an order under varying numbers of business scenarios (Gartner, 2003, p. 1).

Breyfogle (2003, p. 3) and Tibco (2003) further defined BPM as an holistic approach to business

BPM Management discipline Modern technology

+

=

Total quality management BPM application

Business process reengineering Application development Business process motivation Systems integration Process innovation Workflow

Business process modelling Transaction management Business process automation

processing. Breyfogle (2003, p. 3) defined BPM as following: (1) Coordination between people and the data in IT systems;

(2) Giving the data context and turning it into meaningful business information (rather than just automatically routing it from system to system);

(3) BPM delivers contextual information to participants in the process, so that the participants can make well-researched and informed decisions in the most efficient way;

(4) From a management perspective, it gathers and analyses process metrics, such as process duration and cost savings, so that performance and value can be accurately tracked.

According to Tibco (2003), BPM allows organizations to: (1) Automate tasks involving information from multiple systems;

(2) Develop rules to define the sequence in which the tasks are performed; (3) Define responsibilities, conditions and other aspects of the process.

BPM (see Figure 2) not only allows a business process to be executed more efficiently, but also provides the tools to measure performance, identify opportunities for improvement and easily make changes in processes to act upon opportunities. The varying approaches above have shown that BPM operates on processes and process improvement activities. BPM consolidates objectives and methodologies, which has been proposed in a number of approaches including process innovation, business process modeling, BPR and business process automation (Rosemann & de Bruin, 2005, p. 1).

Figure 2. Business process steps. Source: Adapted from Hammer, 2003, p. 7.

The Key Characteristics That Differentiate Business Process Management From Business

Process Reengineering

The focus of BPM is to improve organizational productivity and responsiveness, reduce costs and accelerate cycle times. The focus of BPM is a key driver for profitability (Ultimus, 2003, p. 2). The key aspects of BPM and BPR are as follows (see Table 4).

BPR focuses on a very theoretical approach to process change. The objectives of BPR are a “big-bang” implementation, whereby all the processes in an organization are redesigned from scratch, and then re-implemented all at once. BPM, on the other hand, takes a pragmatic approach. BPM complements existing systems within an organization; processes can be automated quickly and then changed incrementally over time to evolve in step with the business (Ehmke, 2004).

Identity process Align Implement Design Convene design teams Prioritise Appoint process managers Appoint process managers

Table 4

Difference Between BPM and BPR

Business process management Business process reengineering (1) Convert paper-based business process into electronic

processes that eliminate paper folders, file folders, documents and the inefficiencies associated with these;

(1) Minimize “as-is” business process analysis;

(2) Completely automate steps by integrating with enterprise applications;

(2) Streamline business operations and leverage the capabilities of the software, and the process inherent in the software package drive the “to-be” process;

(3) Add intelligence to forms to reduce errors of omissions or

inaccurate data; (3) Minimize the number of custom development objects; (4) Incorporate control features that ensure integrity of

processes and compensate for human or system failure;

(4) Focus on the “real” business requirements and challenge processes that merely accommodate the way it has always been done;

(5) Provide real time feedback about the status of processes;

(5) Reduce cost of doing business by eliminating obsolete and inefficient processes, obsolete regulations and controls, lengthy review and approval cycles;

(6) Measure the time and cost of processes so that the processes can be measured.

(6) Ensure business processes are integrated across all impacted functional areas.

Note. Source: Ultimus, 2003, p. 2.

Business Process Management: A Critical Success Factor

The common factors that are critical for the success of BPM are (Rosemann & de Bruin, 2005, p. 2): (1) Organization and cultural change;

(2) Aligning the BPM approach with corporate goals and strategy. BPM must be based on a process architecture, which captures the interrelationships between the key business processes and the enabling support processes and the alignment with the strategies, goals and policies of an organization;

(3) Focusing on the customer and the customer’s requirements; (4) Process measurement and improvements;

(5) The need for a structured approach to BPM, of having process disciplines and fully understood and documented processes that can be supported by a sound methodology;

(6) Top management commitment, involvement and understanding; (7) Process-aware information systems, infrastructure and realignment; (8) Well-defined accountability and a culture receptive to business processes.

Conclusion

BPR is the practice of modeling, documenting, analyzing and redesigning business processes for the purpose of enhancing processes. BPR is not involved in the automation of processes or the continuous monitoring and capturing of data from automated processes. However, BPR can be achieved by simply using paper and pencil without technology involved. BPM, on the other hand, is the practice of modeling, automating, integrating and monitoring business processes for improving the business performance (profitability) of the organization. The early stages of BPM may involve BPR in some cases. In that sense, BPR is a subset of BPM (Khan, 2005).

The objective of this study is to identify the process performance and readiness of an organization to implement business process management. The methodologies in business process reengineering are included to provide a greater insight into the concept. The expectations of business process reengineering exceeded what

business process reengineering in reality delivered to organizations and this provided an opportunity to further evolve business process reengineering.

References

Al-Mashari, M., & Zairi, M. (1999). BPR implementation process: Analysis of key success and failure factors. Business Process Management Journal, 5(1), 87-112.

Armistead, C., & Machin, S. (1997). Implications of business process management for operations management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 17(9), 886-898.

Attaran, M., & Wood, G. G. (1999). How to succeed at reengineering. Management Decision, 37(10). Balle, M. (1995). The business process reengineering action kit. London: Kogan Page.

Berman, S. (1994). Strategic direction: Don’t reengineer without it. Planning Review, 22(6), 18-23.

Breyfogle, F. W. (2003). Leveraging business process management and six sigma in process improvement initiatives. Retrieved from http://www.bptrends.com/publicationfiles

Choi, F. C., & Chan, S. L. (1997). Business process reengineering: Evocation, elucidation and exploration. Business Process Management Journal, 3(1).

Davenport, T. H. (1993a). Process innovation. Harvard Business School Press, 2(1), 3-5.

Davenport, T. H. (1993b). Process innovation: Reengineering work through information technology. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Davenport, T. H., & Short, J. E. (1990). The new industrial engineering: Information technology and business process redesign. Sloan Management Review, 7(2), 11-27.

Detoro, I., & McCabe, T. (1997). How to stay flexible and elude fads. Quality Progress, 30(3), 55-60.

Ehmke, M. (2004, August 26-27). Using business process management to effectively close the gap between business people and technology. Paper presented at the Business Process Management Congress, Sandton.

Gartner. (2003). The business process management scenario. Retrieved from http://www.gartner.com Gartner Research. (2004). When to adopt BPM. Stamford: Gartner.

Hammer, M. (2001). The agenda. United Kingdom: Random House Business Books.

Hammer, M. (2003). Business process in financial services. Retrieved from http://www.microsoft.com.industry/ financialservices/process.mspx

Hammer, M., & Champy, J. (1993). Re-engineering the corporation: A manifesto for business revolution. London: Nicholas Brealey.

Harmon, P. (2003). Business process change: A manager’s guide to improving, redesigning, and automating processes. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers.

Harrington, H. (1991). Business process improvement. London: McGraw-Hill.

Horney, N. F., & Koonce, R. (1995). The missing piece in reengineering. Training and Development, 12(1), 37-44.

Housel, T. J., Bell, A. H., & Kanesky, V. (1994). Calculating the value of reengineering at Pacific Bell. Planning Forum, 1(2), 40-45.

Jacobson, I., Ericsson, M., & Jacobson, A. (1995). The object advantage: Business process reengineering with object technology. ACM Press Books: Addison Wesley.

Jarrar, Y. F., & Aspinwall, E. M. (1999). Integrating total quality management and business process reengineering: Is it enough? Total Quality Management, 10(4), 584-593.

Khan, R. (2005). Ask the expert. Retrieved from http://www2.cio.com/ask/expert/2005/questions/questions2026.html

Khong, K. W., & Richardson, S. (2003). Business process re-engineering in Malaysian banks and finance companies. Managing Service Quality, 13(1), 54-71.

Kiely, T. J. (1995). Managing change: Why reengineering projects fail. Harvard Business Review, 73(2).

Klien, M. M. (1993). IE’s fill facilitator role in benchmarking operations to improve performance. Industrial Engineering, 25(9). Llewellyn, N., & Armistead, C. (2000). Business process management: Exploring social capital within processes. International

Journal of Service Industry Management, 1(3), 225-243.

Manganelli, R. L. (1993). Define reengineering. Computerworld, 27(29), 7-86.

Mckay, A., & Radnor, Z. (1998). A characterization of a business process. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 18(9), 924-936.

Muthu, S., Whitman, L., & Cheraghi, S. H. (1999, November 17-20). Business process reengineering: A consolidated methodology. Paper presented at the 4th Annual International Conference on Industrial Engineering Theory, Applications and Practice, San Antonio, Texas, USA.

Peltu, M., Clegg, C., & Sell, R. (1996). Business process reengineering: The human issues. Business Processes Resource Centre: Warwick University.

Pritchard, J. P., & Armistead, C. (1999). Business process management: Lessons from European business. Business Process Management Journal, 5(1), 10-32.

Rigby, D. (1993). The secret history of process reengineering. Planning Review, 24(7).

Rosemann, M., & de Bruin, T. (2005). Application of a holistic model for determining BPM maturity. Retrieved from http://www.bptrends.com/publicationfiles

Sinur, J., & Bell, T. (2003). A BPM taxonomy: Creating clarity in a confusing market. Retrieved from http://www.gartner.com Smith, H., & Finger, P. (2003). Business process management: The third wave. Florida: Megan-Kiffer Press.

Tibco. (2003). A user’s guide to BPM. Retrieved from http://www.tibco.com/mk/tbpmwp.jsp Ultimus. (2003). An introduction to BPM. Retrieved from http://www.ultimus.com

Zairi, M., & Sinclair, D. (1995). Business process reengineering and process management. Business Process Reengineering and Management Journal, 1(1).

Zairi, M. (1997). Business process management: A boundaryless approach to modern competitiveness. Business Process Management Journal, 3(1), 64.