Effective Strategies Small Retail Leaders Use to Engage

Employees

Dr. Janet L. Deskins*

*

College of Management and Technology, Walden University

DOI: 10.29322/IJSRP.8.11.2018.p8357 http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.8.11.2018.p8357

Abstract- Research suggests that 70% of North American employees are disengaged in the workplace. Some small retail managers lack strategies for engaging employees. Using the employee engagement framework, the purpose of this descriptive case study was to explore successful strategies that small retail managers use to engage employees. The target population was small retail leaders, purposefully selected because of their success with engaging employees at an Orlando, Florida, company. Data collection was through face-to-face interviews with 5 leaders; and a review of archived organizational documents, including company memorandums, central email software, and online customer reviews through social media websites such as Google, Yelp, and Facebook posts. Data were analyzed using inductive coding of phrases and words from participant interviews, whereas secondary data were collected from participant memorandums, the company website, central email software, and online social media posts supporting the theme interpretation through methodological triangulation. The findings on these Orlando leaders revealed that supportive leaders improved employee engagement, direct communication improved employee engagement, and training improved employee performance. Improving employee engagement contributes to social change because small retail managers can use the findings to improve employee engagement through the implementation of effective strategies, direct communication, and training initiatives.

Index Terms- Employee engagement, Effective leader strategies, Personal engagement, Small retail leaders

I. INTRODUCTION

mployee disengagement is at an all-time high in the North American workplace and leads to what is known as an

engagement gap (Saks & Gruman, 2014). Disengagement hinders the productivity of the employee and prohibits an effective workplace environment (Hollis, 2015). When employees become disengaged, they withdraw and defend themselves and promote a lack of connectedness and emotional absence (Shuck, Adelson, & Reio, 2016). High levels of employee engagement provide enhanced job performance, effective commitment, and organizational citizenship behavior, which improve workplace productivity (Albrecht, Bakker, Gruman, Macey, & Saks, 2015).

Researchers have discovered that employee engagement provides a positive working environment in terms of productivity and competitiveness (Shuck & Reio, 2011). Managers who choose to attract and retain high-caliber, committed, productive, and engaged employees should provide strategic methods to meet the working contexts of the role expectations and a subsequent working environment (Albrecht, Bakker, Gruman, Macey, & Saks, 2015). An ethical leadership style from managers creates a moral guidance and encourages employees to interact with coworkers respectfully, thereby, developing and building a trustworthy workplace environment (Babalola, Stouten, Euwema, & Ovadje, 2016).

Companies that have been studied have revealed an increase in employee engagement when managers provided safe workplace practices and a genuine concern for the well-being of their employees (Vitt, 2014). Employees have displayed improved personal accomplishments and an overall connection to well-being when company managers implemented a healthy workplace climate through strategic leadership practices (Shuck & Reio, 2014). Organizations that provided managers with clear, effective, and principled leadership training provide employees with stability, safety, and psychological meaning to their work tasks (Nel, Stander, & Latif, 2015).

Employee engagement is a positive tool to aid organizational leaders to strive and gain a competitive advantage (Anitha, 2014). Companies can gain a competitive advantage when their employees are engaged in their work and believe they can positively influence the success of the organization (Kumar & Pansari, 2016). Employee engagement influences the organizational climate when managers embed strategic practices such as personnel selection, socialization, performance management, and training and development of the employees (Albrecht et al., 2015). Job and organizational engagement indicate positive job satisfaction, organizational commitment, reduced intentions to quit, and organizational citizenship behavior (Saks & Gruman, 2014).

II. STATEMENTOFTHEPROBLEM

The specific business problem that I addressed in this study is that some small retail business leaders lack strategies to engage employees in the workplace.

III. PURPOSEOFTHESTUDY

The purpose of this qualitative descriptive study was to explore strategies that some small retail business leaders use to engage employees in the workplace. The population of the study consisted of five small retail business managers located in Orlando, Florida, who have implemented strategies to engage employees. The implications for positive social change include the potential to enhance leaders’ understanding of effective strategies necessary to increase employee engagement, which may lead to positive social behaviors of employees who can volunteer their time to assist people in the community and society.

IV. CONCEPTUALFRAMEWORK

Shuck and Reio’s (2011) employee engagement theory served as the conceptual framework of the study. Shuck and Reio (2014) expanded on Fredrickson’s (1998) broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions and Kahn’s (1990) theory of engagement, because the employee engagement theory pertains to the workplace climate, employee engagement, and indicators of employee well-being. The employee engagement theory suggests that employees engage in their workplace environment when upper-echelon leaders orchestrate the firm’s resources into a unique motivational capability (Barrick, Thurgood, Smith, & Courtright, 2015). The three key constructs underlying the employee engagement theory are (a) cognitive engagement, (b) emotional engagement, and (c) behavioral or physical engagement at work (Barrick et al., 2015). Rana, Ardichvili, and Tkachenko (2014) noted that organizational leaders use Shuck and Reio’s (2011) theory to predict financial performance levels based on employee engagement. Sarti (2014) noted that an employee’s opportunities for development in learning and personal growth could affect employee engagement. Furthermore, Shuck and Reio (2014) observed that the key employee engagement constructs represent the intention to act and encompass motivation-like qualities separate from constructs such as job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The employee engagement theory served as a potential lens through which the exploration of the participants’ perceptions and experiences was used to improve employee engagement. Shuck and Reio’s (2011) employee engagement theory aligns with my study by providing a potential means for understanding the strategies that retail leaders use to improve employee engagement.

V. LITERATUREREVIEW

The purpose of this qualitative descriptive study was to explore strategies that some small retail business leaders use to engage employees in the workplace. Employee engagement, as described by Anitha (2014), is an effective tool that organizational managers can strive to achieve to gain a

competitive advantage within their industries. A researcher can gain knowledge on employee engagement but must understand how work conditions may encourage positive job performance that affects the employees’ experience of being engaged (Shuck, Collins, Rocco, & Diaz, 2016). Leaders who strategically implement positive employee engagement practices experience enhance employee job performance, organizational citizenship behaviors, higher productivity, and advanced levels of employee commitment (Popli & Rizvi, 2016).

VI. EMPLOYEEENGAGEMENTTHEORY

Shuck and Reio (2011) introduced the employee engagement theory in human resource development. Byrne et al. (2017) noted there is no single definition of employee engagement and most researchers rely on Kahn’s (1990) theory of personal engagement. Shuck and Reio based their theory on Kahn’s personal engagement concept and created three separate facets: cognitive engagement, emotional engagement, and behavioral engagement. Shuck and Reio revealed that leaders must remain at the forefront of the emerging engagement conversation. In 2008, academy-sponsored conferences began publishing engagement proceedings and in 2009, the first article termed the phrase employee engagement

in an Academy of Human Resource Development sponsored journal (Shuck & Reio, 2011). Shuck and Reio remarked that employee engagement lacks a certain level of consistency in definition and application where some scholars view the term as a reconceptualization of other well-researched variables. Other researchers advocate and address the distinctiveness of employee engagement and leave a gap for scholarly exploration (Shuck & Reio, 2011). A working relationship exists between employee engagement and job performance (Shuck & Reio, 2014).

Shuck and Reio readdressed the development of employee engagement and found that poor workplace engagement deemed detrimental to organizations because of a decrease of employee well-being and productivity (Shuck & Reio, 2014). Shuck and Reio’s (2011) employee engagement theory includes the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral energy of the employee, and the authors found a transition beyond the traditional predictors of workplace performance and into employee job attitudes. The findings of the researchers revealed employee engagement as more predictive of task performance than intrinsic motivation, job immersion, and job fulfillment (Shuck & Reio, 2014). The researchers noted a link of higher levels of employee engagement with an organization’s overall revenue (Shuck & Reio, 2014). Gilbert, Laschinger, and Leiter (2010) suggested evidence-based strategies where managers can empower employees and emphasize individual contributions toward organizational goals as pertinent steps in producing a positive workplace environment toward engagement.

employees (Vitt, 2014). Anitha (2014) identified work environment, leadership, team and co-worker relationships, training and career development, compensation, organizational policies, and workplace well-being as the driving factors towards employee engagement.

Employee engagement through a critical lens is one of privilege and power on who (a) controls the context of the work, (b) determines the experience of engagement, (c) defined the value of engagement, and (d) benefits from high levels of engagement (Shuck et al., 2016). Shuck et al. declared both the organization and employee benefit from the outcomes associated with the experiences of employee engagement. Employee engagement is a separate construct from job satisfaction, as it relates to the active, work-related positive psychological state of the employee (Nimon et al., 2016). Barrick et al. (2015) revealed engagement as an organizational-level construct influenced by organizational practices that are motivationally focused. Sarti (2014) stated engagement as a characterization of vigor, dedication, and absorption.

Researchers communicated how a positive leadership has an indirect effect on the work engagement and job satisfaction of employees with life fulfillment through a psychological empowerment (Nel et al., 2015). Other empirical research has provided evidence on the utility of employee engagement beyond the traditional workplace performance, such as job attitudes (Shuck & Reio, 2014). Leaders can address the workplace environment by evaluating the needs of the employees and create a positive impact of staff productivity (Hollis, 2015).

Bakker (2011) suggested that engaged employees could create their own person-job (P-J) relationship and increase their P-J fit perceptions. Even so, engaged employees might learn to increase their skills at work and meet or exceed the job requirements more effectively through a positive environment of psychological or financial rewards (Lu et al., 2014). Similarly, researchers discovered that employees recognized the importance of well-being, positive psychological, and eudemonic dimensions of engagement (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014).

Employees are the backbone of the organization and workplace engagement is vital to the organization’s success (George & Joseph, 2014). Airila et al. (2014) studied work engagement over 10 years and found resourceful jobs and positive self-esteem play an important role in maintaining and promoting work ability and possibly decreasing employees’ intentions to retire early from the organization. Successful employee engagement results in improved financial revenues to the organization as a positive construct and predictor of contextual performance above and beyond the positive effects of job satisfaction (Byrne et al., 2017).

Development of successfully engaged employees requires a certain amount of investment on behalf of the organization and its leaders (Shuck & Rose, 2013). The investment from the organization goes beyond a monetary one and involves the strategic application by the company managers. Leadership strategies may be required by managers to challenge employees in difficulties and hardships for workplace success (Gawke et al., 2017). The service triangle

indicates a relationship among the organization, the employee, and the customer (Popli & Rizvi, 2017). Popli and Rizvi found engagement has a positive relationship to customer satisfaction. Therefore, a positive customer experience is derived from a more productive employee, improves customer service, and remains in their job longer (Byrne et al., 2017).

Kahn (1990) created a distinction between the physical, cognitive, and emotional paths in which employees engage and disengage personally. The three facets of employee engagement suggest the construct consists of cognitive engagement, emotional engagement, and behavioral engagement (Shuck & Reio, 2011). Shuck and Reio combined the works of researchers on the newly developing topic of employee engagement and set out to assist organizations in developing strategic methods of capturing their employees’ attention, dedication, and longevity. By leaders implementing the facets of cognitive engagement, emotional engagement, and behavioral engagement, employees may experience positive emotions that draw them into an expansion of their human capital (Fredrickson, 1998). The three constructs of employee engagement are necessary conditions for employee engagement; mostly towards psychological meaningfulness, workplace safety, and employee availability (Barrick et al., 2015).

VII. COGNITIVEENGAGEMENT

The concept of cognitive engagement construct involves employees appraising their work environment on whether the work is meaningful and safe, as well as if there are adequate resources to complete their work (Kahn, 1990). Cognitive engagement is a delicate phenomenon that is both challenging to develop and tough to sustain because of the interpretation of the work environment (Shuck & Reio, 2014). Shuck and Reio stated employees use the cognitive decision-making process to determine the overall worth of the circumstances in a silent effort to begin the process of work engagement. An employee’s cognitive or intellectual resources may improve through a manager’s strategic engagement within the workplace and may provide employees with a means of inspired exploration on the job (Fredrickson, 1998).

Employees become physically involved in their work tasks and cognitively vigilant while empathically connecting to others through their performance of the job and how they display what they think and feel (Kahn, 1990). An employees’ cognitive engagement revolves around the way the employee understands their job, the company, and the environment of the workplace (Shuck & Reio, 2011). Shuck and Reio (2011) stated that cognitive resources allow the employee to experience positive emotions to momentarily draw on the expansion of their human capital. Therefore, a joyous employee is more apt to be flexible, creative, and use critical thinking skills on the job (Shuck & Reio, 2014). Researchers have discovered that cognitive flexibility presents a positive association between the employee’s thoughts and manner of mental processing to complete the assignment (Wong et al., 2016). Once employees appraise the circumstances as a positive work encounter, they can move to the next process of emotional engagement (Shuck & Reio, 2014).

on any one person, object, or behavior (Saks & Gruman, 2014). The interactions are responsive and provide supportive attachments imparting a sense of safety, and provoke positive emotions (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2017). Bakker (2011) noted that job resources become salient when high job demands expand employees’ emotional and cognitive abilities.

VIII. EMOTIONALENGAGEMENT

Employee satisfaction is an emotional reaction of the employee engaging in the job circumstances and other work factors, such as the leadership qualities of the manager and cohesion of the co-workers (Kumar & Pansari, 2016). The participation of engagement is a role of performance for the employee (Rana et al., 2014). Researchers suggest the level in which an employee engages on the job includes an emotional factor of engagement in work-related tasks (Shuck & Reio, 2014). An employee’s emotional bond in their work creates a willingness to involve personal resources such as pride, belief, and knowledge (Shuck & Reio, 2011).

An employee’s emotional engagement is a bond with their organization and is an important determinant of commitment and loyalty (Shuck & Reio, 2011). An emotionally engaged employee has a positive attitude in the workplace, values the system, and goes beyond the call of duty to perform their role in excellence (Anitha, 2014). The self-management process requires an employee to use and make sound decisions on the meaningfulness or purpose of their job and in the manner of making the right choice and in the right way (Saxena & Srivastava, 2015). Researchers have proved that formally negative emotions from employees have been reversed into positive emotions of engagement with psychological actions of readiness (Fredrickson, 1998).

Researchers discovered the emotional engagement of employees to be a collective phenomenon which spreads from individual to individual (Rana et al., 2014). Other researchers’ findings exposed that employees thrive on intrinsic rewards the employee may receive from the work performed and act as reinforcements to keep the employee actively self-managing and engaged in their work (Saxena & Srivastava, 2015). Emotional engagement produces emotional responses from employees that lead to behavior patterns, or behavioral engagement actions on the job (Karatepe & Aga, 2016).

IX. BEHAVIORALENGAGEMENT

Behavioral engagement is the most evident form of employee engagement (Shuck & Reio, 2011). Researchers observed that cognitive and emotional engagement spawns the physical manifestation of discretionary behavioral engagement (Shuck et al., 2016). Circumstances within the job appear as fleeting contracts to the employee and if certain conditions are met, the employee deems these conditions as acceptable and can personally engage in moments of task behaviors (Kahn, 1990). The employee’s perception of the job objective allows for a positive reaction of behavior based on the motivation from encouraging managers (Hackman & Oldham, 1976).

Leaders who identify a style that works best for a situation and matches the expectations of the employees brings

forth high levels of engagement for better work performance through improved employee behavior (Popli & Rizvi, 2016). Changes in behavioral patterns occur during positive emotions and broaden a person’s momentary thought-action repertoire (Fredrickson, 1998). Behavioral engagement allows the employee to broaden their available resources and openly display these behaviors in the workplace (Shuck & Reio, 2014). Fredrickson further claimed certain positive emotions prompt individuals to abandon instinctive behavioral scripts and pursue innovative, creative, and unscripted paths of thoughts and actions. Positive behavioral engagement from employees may create an interaction with customers who may talk positively about the brand and recommend the brand or service to their family and friends (Kumar & Pansari, 2016). Employee job performance satisfaction and high levels of commitment benefit the organization through positive behavioral engagement actions (Rana et al., 2014). The social implications of behaviorally engaged employees predict a health working environment that reflects the social impact of the organization (Anitha, 2014).

X. EFFECTIVEEMPLOYEEENGAGEMENTSTRATEGIES Effective employee engagement strategies may include managers who implement meaningful work characteristics like self-actualizing work, social impact, feelings of personal accomplishment, and perceived ability to meet the employee’s projected career goals (Shuck & Reio, 2011). Gilbert et al. (2010) suggested engagement strategies to empower employees and emphasize individual contributions to organizational goals as important steps in producing positive workplace environments. Managers who focus on engaging employees may also engage customers through listening, servicing, and treating the customer in the best manner (Kumar & Pansari, 2016). However, organizational leaders should ensure all levels of hierarchy are involved in fostering employee engagement to improve the cultural setting (Rana et al., 2014).

Workplace practices of enhanced recruitment and safe work environments showed an increase of employee engagement with excellent retention, stronger customer relationships, and a deeper understanding of organization (Vitt, 2014). Managers who empower employees enhance employee feelings of self-efficacy (Nel et al., 2015). Researchers also proved that engaged employees present a competitive advantage in the marketplace for the organization (Glavas, 2016).

Moreover, engaged employees who analyze the strategic structure of their firm generate shared perceptions and collectively engage as a group (Barrick et al., 2015). Managerial support presents a positive contribution to the organization and a feeling of value to the employees (Shuck & Reio, 2014). The role performed by employees reveals a dimension of self-expression and the use of skills within their designated roles (Kahn, 1990). Therefore, managers who offer a positive perception of the work environment present a supportive workplace for employee engagement (Anitha, 2014). Managers who reengage their employees through a thoughtful change intervention benefit the entire organization (Shuck & Reio, 2011).

and executing organizational strategies, facilitating workplace changes, generating effective working environments, ensuring operations run efficiently, building up and motivating teams and individuals (Agarwal, 2014). Self-efficacy is partially the mediator between the manager’s rated effectiveness and employee engagement (Ugwu et al., 2014).

Communicate with employees. Communicating with people is a means to the manager figuring out the best method to respond to certain situations with employees (Kahn, 1990). Technology offers managers an effective way to communicate and engage with their employees (Men & Hung-Baesecke, 2015). Managers can build trust with employees by implementing internal campaigns such as kick-off meetings, flyers and announcements via the company’s intranet, and publishing articles in the company’s magazine (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Strategic managers work with employees to improve time management skills and help them learn effective communication skills to increase their job effectiveness (Byrne et al., 2017). According to Gordon et al. (2015), communication helps employees perform their daily work tasks and enhance both their and other’s professional development.

Share knowledge. Communication of the manager’s knowledge allows for knowledge sharing of the company’s procedures with employees (Ford et al., 2015). Leadership traits include the manager’s motives, values, social and cognitive ability, and knowledge; which they share with their employees (Offord et al., 2016). Researchers have found knowledge sharing and innovation encourage creativity and participation among employees (Martinez, 2015). Kahn (1990) stated effective leaders share their personal philosophy and vision with employees to build relationships. Knowledge sharing among team members also fosters individual and team creativity and employee engagement (Dong, Bartol, Zhang, & Li, 2016). Internal knowledge sharing promotes proactive work behaviors where the behavioral characteristics of the employees reveal initiative, risk taking, and the introduction of innovative ideas (Gawke et al., 2017).

Provide employee resources. Job resources refer to the physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job function that help the employee achieve their work goals (Balunde & Paradnike, 2016). Sufficient job resources may provide employees with a sense of security to improve their engagement practices (Byrne et al., 2017). Job resources provide employees with greater learning opportunities and have direct effects on increasing work engagement (Sarti, 2014). Managers should seek resources to positively associate with employee engagement practices where employees can seek challenges to associate adaptivity and reduce demands from a negative environment (Petrou, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2016). Job resources, along with the employees’ personal resources, help to balance the employee’s personal abilities and needs (Gawke et al., 2017).

Empower employees. Empowerment allows a person to feel the need to serve, aspire, and respect the power and receive the support of their supervisor (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2017). Social media outlets allow employees to articulate their opinions and engage in a more personalized and intimate relationship with the organization (Men & Hung-Baesecke, 2015). Transformational leaders empower their employees, and

provide a leader-member exchange, influence forms of engagement in the workplace (Saks & Gruman, 2014). Therefore, empower your employees and give them freedom to make decisions, respect their failures, and let them learn lessons from those failures so they can become successful leaders (Rao, 2017).

Encourage employees. Employees with low morale are likely to view their manager as disengaged and unethical (Bonner et al., 2016). Adequate salary and career opportunities may provide employees with the motivation to engage in high work performance (Balunde & Paradnike, 2016). Some managers may use a reward system to encourage and stimulate employees to engage in their job functions (Peng et al., 2016). Managers should pay attention to improving their personal integrity as employees soon discover their manager’s integrity builds their own engagement and improves citizenship behaviors (Reunanen, Penttinen, & Borgmeier, 2017).

Build trustworthiness. Researchers noted that without trust, employees focus on placing blame on others, miss deadlines, fail to service customers efficiently and fail to deliver positive results (Rao, 2017). Transparency among management builds a relationship of trust with the employees (Men & Hung-Baesecke, 2015). Employee engagement, as an organizational strategy should be a leadership goal of managers that involves all members of the organization and one that offers a supportive culture and builds on trust (Popli & Rizvi, 2017). When managers provide consistent responsiveness and attention, individuals develop positive internal processes of trustworthiness (Byrne et al., 2017). Trust in the supervisor creates the development of an employee’s social capital outcome and positive attitudes and behaviors (Lapointe & Vandenberghe, 2016). Employees who believe in the wow factor in their work environment are more likely to lead results and transfer the excitement and engagement forward to others (Reunanen et al., 2017). Trust allows individuals to fulfill their job roles in an efficient manner (Trépanier, 2014).

Link engagement to high performance. Employee engagement is a motivational state where employees invest themselves emotionally, cognitively, and physically in their work role (Kahn, 1990). Employees who demonstrate high performance skills in their job are more likely to further develop their cohesion levels and be a benefit to the entire organization in future tasks (Rodríguez-Sánchez, Devloo, Rico, Salanova, & Anseel, 2016). Managers can customize individual performance levels for each employee and in turn, create influence follower development by communicating lofty expectations and stimulate followers’ intrinsic needs for growth (Dong et al., 2016). High performers want to believe their work is meaningful and believe they can give and receive in their work role (Kahn, 1990). Superior job performance boosts employee engagement and self-efficacy because it encourages motivation-enhancing experiences of excellence and success (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014).

collective goals, and establishing themselves as a role model for the team (Dong et al., 2016). Employees observe managers and respond well to leaders who lead through example (Zhu, Treviño, & Zheng, 2016).

A responsive leader repeats interactions with responsive and supportive actions to their employees and creates a cohesive pattern where the employees can psychologically function on the job (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2017). Effective leaders also leverage the talents of others so business-oriented leaders can focus on their business roles within the organization and perform their tasks more efficiently (Rucker, 2017). A leadership strategy with a scheme of effective nurturing and collaborative capabilities draws employees towards engagement in their work roles (Beckmann, 2017). Inspirational leaders close the gap between themselves and employees and develop positive employee engagement in the workplace (Rao, 2017).

XI. FACTORSTHATENHANCEEMPLOYEEENGAGEMENT Employee engagement is a level of commitment and involvement an employee has towards their organization and company values (Anitha, 2014). According to researchers, many leaders are turning to scholars to test strategies on how to develop an engaged workforce (Shuck & Reio, 2011). Job crafting links work engagement and opens opportunities for individuals to expand their career (Lu et al., 2014). A fair pay structure creates a sense of self-efficacy for the employee and promotes employee engagement (Olafsen, Halvari, Forest, & Deci, 2015). Shuck, Adelson, and Reio (2016) noted how engaged employees bring their whole selves into their work roles. Kahn’s (1990) personal engagement foundation reveals that engaged employees show cognitive attentiveness, become emotionally vested, and are physically energetic in the work environment.

Leadership. Leadership was an important criterion identified through research as a fundamental factor to employee engagement (Anitha, 2014). Researchers suggested leadership as one of the largest factors affecting employee perceptions and the workplace and workforce engagement actions (Popli & Rizvi, 2016). Effective leaders translate organizational systems to their employees and reinforce their behaviors to create different degrees of supportiveness and openness (Kahn, 1990). Kahn further stated supportive managers create a supportive environment that allow employees to try and to fail without fear of the consequences. Leaders who inspire employees create trust through civility, honest communication, and concern towards a healthy workplace (Hollis, 2015). Managers should recognize and implement focal areas of employee development that require immediate attention (Kumar & Pansari, 2016).

Organizational leaders can enhance employee engagement through effective use of current resources or in purchasing external resources and develop new capabilities to create improved employee and customer value (Barrick et al., 2015). The positive leadership role of managers in an organization help develop reliable and valid perceptions by the employees towards their work environment (Nel et al., 2014). Managers need the ability to facilitate directions to employees in a manner of collaboration; instead of enforcing the power of one over another (Shuck et al., 2016). When employees are

encouraged and supported by their managers, they are willing to engage in the workplace environment to help their organization achieve functional and social success (Paillé et al., 2014).

Fair pay. Workers associate fair compensation with task assignment and task completion (Borromeo, Laurent, Toyama, & Amer-Yahia, 2017). Fair compensation systems attract and retain valuable employees based on their heterogeneous ability, motivation levels, and social relationships (Larkin & Pierce, 2015). Samnani and Singh (2014) reported that performance-enhancing compensation practices help to increase employee productivity through greater accountability.

Employees tend to engage in their work efforts based on what they consider fair wages (Cohn, Fehr, Herrmann, & Schneider, 2014). According to Borromeo et al. (2017), engaged workers may contribute more than their disengaged counterparts if they believe their wages are fair. Larkin and Pierce (2016) noted that fair wages encourage engaged employees to work harder, obtain promotions in the workplace, and increase their psychological well-being.

Responsible organizational leaders influence a culture that drives employee engagement and compensates their workers to ensure fairness and employee satisfaction in the workplace (Taneja, Sewell, & Odom, 2015). Compensation motivates an employee to achieve more and therefore focus more on their work and personal development within the organization (Anitha, 2014). Therefore, compensation systems represent a critical influence and driver of employee attitudes and behaviors towards employee engagement in the workplace (Samnani & Singh, 2014).

Cultural diversity. A healthy working environment should consist of a moral cultural diversity that includes an effective team, an attentive manager, job security, a sustainable compensation package, proper resources, and a safe working environment (Anitha, 2014). Productive and successful firm cultures are comprised of skillful employees who perform routines with knowledge of organizational processes and a full understanding of the daily operations (Charlier et al., 2016). Kish-Gephart et al. (2014) stated that fairness generates moral standards and honest motives across corporate culture.

Effective employee engagement affects all work groups, industries, and organizational cultures and requires dedication from managers and employees (Shuck et al., 2016). Employee engagement combines an affective commitment and intrinsic motivation between an employee’s attachment and relationship with the organizational culture and colleagues (Taneja et al., 2015). Organizational culture influences whether an employee chooses to engage in their work and is based on the work environment (Reis, Trullen, & Story, 2016). The key competitive advantage of a firm is to attract top talent, apply strategic practices, develop respectable leadership, and engage employees within a healthy organizational culture of motivated employees (Evangeline & Ragavan, 2016).

(a) narrative, (b) ethnography, (c) grounded theory, (d) case study, and (e) phenomenology (Palinkas et al., 2015). The phenomenon explored for this study encompassed retail managers with experience in using successful strategies to engage employees within the workplace. A single case study design is the most appropriate choice for this research because the data collected was consistent with the topic of the study and phenomenon of successful practices by managers in employee engagement.

The population for this qualitative single-case study included managers from a small business who were based in Orlando, Florida. Purposeful sampling is the desired sampling method choice of qualitative researchers, and the essence of purposeful sampling is to select information-rich cases that allow for the highest level and use of limited resources from diverse conditions (Duan Bhaumik, Palinkas, & Hoagwood, 2015). Purposeful sampling was used to select the study participants.

Sample sizes are typically small in qualitative research studies; nevertheless, the researcher should address credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Brown, Strickland-Munro, Kobryn, & Moore, 2017). The justification of sample size is evident in the data reaching the saturation point of redundancy, however a sample size may include three

semistructured interviews (Campbell, 2015; Marshall, Cardon, Poddar, & Fontenot, 2013). In qualitative work, the sample size is generally small and based on similar research on the same topic (Karimi et al., 2017). A homogenous population should consist of six and 12 participants for the researcher to obtain data saturation (Saunders & Townsend, 2016). However, this study consisted of five eligible managers from a retail business who implemented successful strategies to engage employees in the workplace.

Participants met the eligibility criteria as managers leading successful teams through strategic engagement practices. Data was collected from five managers with semistructured, open-ended, and in-depth interview questions. Managers who participated in the study had at least 1 year of leadership experience and met the criteria for inclusion in this study. Secondary data from company memorandums, central email software, and online customer reviews provided information towards data collection and validation for the past 5 years (2012-2016).

Fusch and Ness (2015) defined data saturation as a difficult task for the researcher, as the ability to reach data saturation depends on the varying available studies and willing participants. In qualitative inquiry, there is a purposeful strategy of ambiguities where the researcher examines the purpose of the inquiry, seeks what is at stake, provides useful data of credible input, provides information throughout the available time, and incorporates the obtainable resources as a method to reach redundancy (Marshall et al., 2013). The most suitable unit of investigation in reaching data saturation is sufficiently large enough, but small enough for the researcher to provide relevant meaning for the reader to evaluate the trustworthiness of the findings (Elo et al., 2014). Data saturation was reached with five participants and the data collection process ceased.

Participant eligibility includes a series of criteria which the researcher identifies to enable a consensual evaluation guide for a qualitative study (Santiago-Delefosse, Gavin, Bruchez,

Roux, & Stephen, 2016). The rationale of selecting participant criteria is for the researcher to strategically categorize areas of unique, different, or important perspectives on the phenomenon in question (Robinson, 2014). In qualitative methodology, the researcher selects participants who meet or exceed a specific set of criteria and who can share intimate knowledge of the phenomenon toward an information-rich case study (Palinkas et al., 2015).

To determine the eligibility criteria, the experience of each participant was evaluated with their employee engagement strategies in the retail industry. Eligible participants need at least one year of management experience and knowledge related to the phenomenon (Karimi et al., 2017). Flexibility in criteria allows the researcher to meet the needs and specificities of the study and present a consensual and explicit evaluation protocol of the participants (Santiago-Delefosse et al., 2016). The appropriate participants needed management experience and proven leadership skills to fulfill the requirements of this study.

XIII. DATACOLLECTIONINSTRUMENTS

As the data collection instrument, the semistructured method was used with open-ended, and in-depth interview questions to gather data for this study. An investigation of the organizational documents included administrative memorandums for the past 5 years (2012-2016). Directly following the interview process, member checking was incorporated to confirm the validity of each participant’s responses. By validating the correct interpretation of each participants’ data, the information was solidified as credible and ensured the truthfulness of the information to eliminate any potential interview misinterpretations.

The interview process was the principal foundation of data collection for this study. As the data collection instrument, both advantages and disadvantages occurred. One advantage is in how interviewers ask open-ended and relevant questions during the interview process (Chan et al., 2013). Another advantage is that an interviewer can observe the reactions of participants and make assumptions of the freely-given responses by the

individuals (Saunders & Townsend, 2016). A disadvantage, as described by Paulo et al. (2015), is a participants’ attitude and failure to release information could be a deterrent to the progression of the research. Another disadvantage is the researcher’s tendency to misinterpret nonverbal cues during the interview process and make incorrect assumptions (Lin et al., 2016). Potential advantages and disadvantages were incorporated into the interview process. To prevent misinterpretations, participants were asked to clarify their response to the interview questions and were encouraged to provide any additional information.

XIV. FINDINGSOFTHESTUDY

their employees successfully. The data emanated from semistructured interviews with the participants and in reviewing of the company’s memorandums, job description criteria, central email software, and online employee reviews by the company’s customers. Audio files were uploaded, interviews were transcribed, and all of the interview data, company policies, and documentation were entered into NVivo 11 software. NVivo software was used to organize the text data, code the text, and manipulate the text data to display the desired codes. Finally, the themes were generated from the node attributes and queries from the participant responses through the NVivo 11 program. After analyzing the data in NVivo 11, three major themes emerged. These three themes included (a) supportive leadership improved employee engagement, (b) direct communication improved employee engagement, and (c) training improved employee performance.

Theme 1: Supportive Leadership Improved Employee Engagement

The findings in the study identified the described theme of supportive leadership and improved employee engagement. Employee engagement, according to Karatepe and Aga (2016), has a positive effect on the workplace environment. All participants (P1, P2, P3, P4, and P5) demonstrated supportive leadership by building effective working relationships and by listening to their employees and encouraging teamwork. Most of the participants (P1, P2, P4, and P5) shared that the employees accomplished their tasks efficiently because managers dedicated time to the employees through constant discussions and guidance. Several of the participants revealed that employee engagement is identified when the employee becomes a benefit to the business by completing their job assignments through managerial support (P1, P2, and P4). Byrne et al. (2017) revealed that supportive leaders engage employees to perform effectively and produce higher results that benefit the employee and the company.

Based on a comprehensive review of company

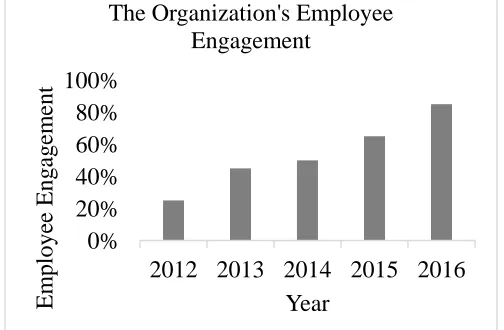

[image:8.612.38.290.526.691.2]memorandums on employee engagement, managers documented these improvements based on their supportive leadership. Figure 1 reflects the organization’s 5 years (2012–2016) of engagement.

Figure 1. 5-year (2012–2016) employee engagement increases in the company.

The data in Figure 1 shows that the overall engagement levels drastically improved from 2012 during the next 5 years. The data in Figure 1 shows that the employee engagement levels in 2012 was 25%. In 2013, the engagement was 40%, which is an increase of 15%. In 2014, the engagement was 50%, which is an increase of 10%. In 2015, the engagement was 60%, which is an increase of 10%. In 2016, the engagement was 80%, which is an increase of 20%. The improvement in employee engagement over the past 5 years is due to managers listening, discussing, and working alongside of their employees (P1, P2, P3, P4, and P5). All managers revealed that employee engagement improved by 60% during a 5-year period (P1, P2, P3, P4, and P5).

The findings represented in this theme convey that supportive managers dedicate time with employees through documented memorandums, open discussions, and in their guidance in job-site duties. The supportive strategies used by these managers helped to improve the company’s effective business practices on employee engagement over five years (2012–2016). Shuck and Reio (2014) noted that managerial support provides a positive contribution to the organization and a feeling of value to the employees. Anitha (2014) found that managers who offer a positive perception of the work environment present a supportive workplace for employee engagement. Therefore, managers who engage their employees through a thoughtful change intervention provide a benefit to the entire organization (Shuck & Reio, 2011).

Theme 2: Direct Communication Improved Employee Engagement

The findings represented in Theme 2 aligned with the findings of Shuck et al. (2016) that employee engagement affects all work groups in the organization and requires direct

communication from managers and employees. P1 used a calm speaking voice as a gentle approach of direct communication to give instructions to employees. Most participants (P1, P2, and P5) praised their employees with direct and immediate

communication as the employee performed their job function. P5 preferred the employees directly communicate with each other and share information with the group so everyone could learn together. Each manager (P1, P2, P3, P4, and P5) expressed an understanding of the process of direct communication and positively encouraged their employees to engage in their work.

Direct communication creates behaviors to develop an employee’s social capital outcome and build trust in the organization (Lapointe & Vandenberghe, 2016). Honest

communication creates trust between the employee and manager and provides for a healthy workplace environment (Hollis, 2015). The findings of direct communication in the workplace were consistent with the literature from Byrne et al. (2017) who revealed that strategic managers work with employees to expand their skills and help employees learn effective communication skills to improve engagement.

Theme 3: Training Improved Employee Performance

The findings aligned with the study by Samnani and Singh (2014) where the researchers found performance-enhancing compensation practices helped to increased employee productivity through greater accountability. Additionally, the findings from the participants aligned with Kumar and Pansari’s

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

E

m

pl

oye

e E

nga

ge

m

ent

Year

The Organization's Employee

(2016) review of how effective training may encourage employees to communicate with customers through listening, servicing, and treating the customer in the most effective manner. Nel et al. (2101) noted that training programs result in positive performance towards successful employee performance. Therefore, the findings revealed that employee training may build a direct line of knowledge between the employee and customer towards the utilization of effective customer service practices to improve employee performance.

The findings in Theme 3 aligned with the findings of Nel et al. (2015) that company training improved employee performance because training created stability, safety, and psychological meaning to the employees’ work tasks. According to Lloyd, Bond, and Flaxman (2017), employees perceived intrinsic value in attending training programs and were more apt to learn and use the training material on the job. Albrecht et al. (2015) found that employee engagement influences the organizational climate when managers implement strategic practices such as training and development. Furthermore, Kane (2017) discovered that employers are offering employees with opportunities of organizational grow through technical training and carefully curated work experiences towards career

development.

XV. RECOMMENDATIONS

The purpose of this qualitative descriptive study was to explore strategies that some small retail business leaders use to engage employees in the workplace. While the participants interviewed provided valuable insight and feedback to engage employees effectively, further research is recommended. The limitations identified in Section 1, Limitations, can be addressed in future research by scholars through alternative interview questions. Some of the participants appeared nervous in the recording of their responses. A participant may experience limitations in their response by not recollecting all the specifics related to the strategies used to implement employee engagement. Another limitation can be a participant’s episodic memory, which may have limited the participant to accurately reconstruct their response, based on memory (Szpunar et al., 2013). The lack to recollect from memory may create a false response during the interview. The limitations in replicating past events can be time-consuming and present challenges to the early researchers’ findings(Clement et al., 2015).

Although the findings of this study extend to existing research on employee engagement, employee disengagement was not always the same for each person. Employee engagement contains a human element and creates a complex business problem that future qualitative scholars should explore. A researcher should consider other effective strategies to improve employee engagement. Future research may include the interviewing of employees as an additional means to explore their perceptions of effective strategies that may provide valuable insight on this topic.

Recommendations for further qualitative descriptive research also includes the exploration of effective engagement strategies in different geographical locations and diverse types of retail industries. By exploring employee engagement in diverse geographical locations and industries, future researchers may

contribute to the understanding of employee engagement in the workplace. Future qualitative researchers should consider examining employee engagement within the office environment or the external field environment. Further research may provide managers and leaders with valuable insight to improve employee engagement which may increase productivity, improve sustainability, and approach survivability in a competitive market.

XVI. CONCLUSION

The findings from this qualitative descriptive study revealed that supportive leaders, direct communication, and company training as a management strategy improved employee engagement. According to research findings, disengaged employees represent more than 70% of the workforce in the United States (U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board, 2015). Through investigative research, Shuck and Reio (2016) found engaged employees are more likely to be productive, remain longer with their current employer, and positively interact with customers. Employee engagement through a critical lens is one of privilege and power on who (a) controls the context of the work, (b) determines the experience of engagement, (c) defines the value of engagement, and (d) benefits from high levels of engagement (Shuck et al., 2016).

The findings from this descriptive case study revealed that small retail managers could improve employee engagement by focusing on the supportive leadership styles, exercising direct communication, and investing in company training as a management strategy. Based on the participants’ experiences, managers should implement the above strategies to improve organization’s employee engagement strategy. The findings of this study also indicated that by managers applying the strategies that emerged from the participants’ responses, organizational leaders could increase employee engagement, which leads to organizational productivity as the result of increased performance. Most importantly, implementing these strategies is cost-effective and managers can integrate these recommendations into the organizational engagement strategy.

REFERENCES

[1] Agarwal, U. A. (2014). Linking justice, trust and innovative work behaviour to work engagement. Personnel Review, 43, 41-73. doi:10.1108/PR-02-2012-0019

[2] Airila, A., Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B., Luukkonen, R., Punakallio, A., & Lusa, S. (2014). Are job and personal resources associated with work ability 10 years later? The mediating role of work engagement. Work & Stress, 28, 87-105. doi:10.1080/02678373.2013.872208

[3] Albrecht, S. L., Bakker, A. B., Gruman, J. A., Macey, W. H., & Saks, A. M. (2015). Employee engagement, human resource management practices and competitive advantage: An integrated approach. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 2, 7-35. doi:10.1108/JOEPP-08-2014-0042

[4] Anitha, J. (2014). Determinants of employee engagement and their impact on employee performance. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 63, 308-323. doi:10.1108/IJPPM-01-2013-0008

[5] Babalola, M. T., Stouten, J., Euwema, M. C., & Ovadje, F. (2016). The relation between ethical leadership and workplace conflicts: The mediating role of employee resolution efficacy. Journal of Management, 1-27. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/0149206316638163

[6] Bakker, A. B. (2011). An evidence-based model of work engagement.

Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20, 265-269. doi:10.1177/10963721411414534

[7] Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2014). Burnout and work engagement: The JD–R approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychological and Organizational Behavior, 1, 389-411. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031314-091235

[8] Balunde, A. & Paradnike, K. (2016). Resources linked to work engagement: The role of high performance work practices, employees’ mindfulness, and self-concept clarity. Social Inquiry into Well-Being, 2, 55-62. doi:10.13165/SIIW-16-2-2-06

[9] Barrick, M. R., Thurgood, G. R., Smith, T. A., & Courtright, S. H. (2015). Collective organizational engagement: Linking motivational antecedents, strategic implementation, and firm performance.

Academy of Management Journal, 58, 111-135. doi:10.5465/amj.2013.0227

[10] Beckmann, E. A. (2017). Leadership through fellowship: Distributed leadership in a professional recognition scheme for university educators. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 39, 155-168. doi:10.1080/1360080X.2017.1276663

[11] Bernard, M. (2016). The impact of social media on the B2B CMO.

Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 31, 955-960. doi:10.1108/JBIM-10-2016-268

[12] Bonner, J. M., Greenbaum, R. L., & Mayer, D. M. (2016). My boss is morally disengaged: The role of ethical leadership in explaining the interactive effect of supervisor and employee moral disengagement on employee behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 137, 731-742. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2366-6

[13] Borromeo, R. M., Laurent, T., Toyama, M., & Amer-Yahia, S. (2017). Fairness and transparency in crowdsourcing, 466-469. Advance online publication. doi:10.5441/002/edbt.2017.46

[14] Brown, G., Strickland-Munro, J., Kobryn, H., & Moore, S. A. (2017). Mixed methods participatory GIS: An evaluation of the validity of qualitative and quantitative mapping methods. Applied Geography,

79, 153-166. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2016.12.015

[15] Byrne, Z., Albert, L., Manning, S., & Desir, R. (2017). Relational models and engagement: An attachment theory perspective. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 32, 30-44. doi:10.1108/JMP-01-2016-0006 [16] Campbell, K. (2015). Flexible work schedules, virtual work programs,

and employee productivity (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Full Text database. (UMI No. 3700954)

[17] Charlier, S. D., Guay, R. P., & Zimmerman, R. D. (2016). Plugged in or disconnected? A model of the effects of technological factors on employee job embeddedness. Human Resource Management, 55, 109-126. doi:10.1002/hrm.21716

[18] Chughtai, A., Byrne, M., & Flood, B. (2015). Linking ethical leadership to employee well-being: The role of trust in supervisor.

Journal of Business Ethics, 128, 653-663. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2126-7

[19] Clement, S., Schauman, O., Graham, T., Maggioni, F., Evans-Lacko, S., Bezborodovs, N., ... & Thornicroft, G. (2015). What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological medicine, 45, 11-27. doi:10.1017/S00332917140000129

[20] Cohn, A., Fehr, E., Herrmann, B., & Schneider, F. (2014). Social comparison and effort provision: Evidence from a field experiment.

Journal of the European Economic Association, 12, 877-898. doi:10.1111/jeea.12079

[21] Dong, Y., Bartol, K. M., Zhang, Z. X., & Li, C. (2016). Enhancing employee creativity via individual skill development and team knowledge sharing: Influences of dual‐focused transformational

leadership. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38, 439-458. doi:10.1002/job.2134

[22] Duan, N., Bhaumik, D. K., Palinkas, L. A., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Optimal design and purposeful sampling: Complementary methodologies for implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42, 524-532. doi:10.1007/s10488-014-0596-7

[23] Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative content analysis. Sage Open, 4(1), 1-10. doi:1-10.1177/2158244014522633

[24] Evangeline, E. T., & Ragavan, V. G. (2016). Organisational culture and motivation as instigators for employee engagement. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 9(2) 1-4. doi:10.17485/ijst/2016/v9i2/86340

[25] Ford, D., Myrden, S. E., & Jones, T. D. (2015). Understanding “disengagement from knowledge sharing”: Engagement theory versus adaptive cost theory. Journal of Knowledge Management, 19, 476-496. doi:10.1108/JKM-11-2014-0469

[26] Fortenberry Jr., J. L., & McGoldrick, P. J. (2016). Internal marketing: A pathway for healthcare facilities to improve the patient experience.

International Journal of Healthcare Management, 9, 28-33. doi:10.1179/2047971915Y.0000000014

[27] Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2, 300-319. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300 [28] Fusch, P. I., & Ness, L. R. (2015). Are we there yet? Data saturation

in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 20, 1408-1416. Retrieved from http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/

[29] Gawke, J. C., Gorgievski, M. J., & Bakker, A. B. (2017). Employee intrapreneurship and work engagement: A latent change score approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 100, 88-100. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2017.03.002

[30] George, G., & Joseph, B. (2014). A study on employees’ engagement level in travel organisations with reference to Karnataka. Indian Journal of Commerce and Management Studies, 5, 8-15. Retrieved from http://scholarshub.net

[31] Gilbert, S., Laschinger, H. K., & Leiter, M. (2010). The mediating effect of burnout on the relationship between structural empowerment and organizational citizenship behaviours. Journal of Nursing Management, 18, 339-348. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01074.x [32] Glavas, A. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and employee

engagement: Enabling employees to employ more of their whole selves at work. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(796), 1-10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00796

[33] Gordon, H. J., Demerouti, E., Bipp, T., & Le Blanc, P. M. (2015). The job demands and resources decision making (JD-R-DM) model.

European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24, 44-58. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2013.842901

[34] Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16, 250-279. doi:10.1016/0030-5073(76)90016-7 [35] Hollis, L. P. (2015). Bully university? The cost of workplace bullying

and employee disengagement in American higher education. SAGE Open, 5(2), 1-11. doi:10.1177/2158244015589997

[36] Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 692-724. doi:10.2307/256287

[37] Kane, G. (2017). The evolutionary implications of social media for organizational knowledge management. ScienceDirect, 27, 37-46. doi:10.1016/j.infoandorg.2017.01.001

Journal of Bank Marketing, 34, 368-387. doi:10.1108/IJBM-12-2014-0171

[39] Karimi, M., Brazier, J., & Paisley, S. (2017). How do individuals value health states? A qualitative investigation. Social Science & Medicine, 172, 80-88. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.027

[40] Kish-Gephart, J., Detert, J., Treviño, L. K., Baker, V., & Martin, S. (2014). Situational moral disengagement: Can the effects of self-interest be mitigated? Journal of Business Ethics, 125, 267-285. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1909-6

[41] Kumar, V., & Pansari, A. (2016). Competitive advantage through engagement. Journal of Marketing Research, 53, 497-514. doi:10.1509/jmr.15.0044

[42] Lapointe, É., & Vandenberghe, C. (2016). Trust in the supervisor and the development of employees’ social capital during organizational entry: A conservation of resources approach. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1-21. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/09585192.2016.1244097

[43] Larkin, I., & Pierce, L. (2016). Compensation and employee misconduct: The inseparability of productive and counterproductive behavior in firms. Organizational Wrongdoing, 10, 1-27. Advance online publication. doi:10.1017/CB09781316338827.011

[44] Lloyd, J., Bond, F. W., & Flaxman, P. E. (2017). Work-related self-efficacy as a moderator of the impact of a worksite stress management training intervention: Intrinsic work motivation as a higher order condition of effect. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22, 115-127. doi:10.1037/ocp0000026

[45] Lu, C. Q., Wang, H. J., Lu, J. J., Du, D. Y., & Bakker, A. B. (2014). Does work engagement increase person–job fit? The role of job crafting and job insecurity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 84, 142-152. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2013.12.004

[46] Marshall, B., Cardon, P., Poddar, A., & Fontenot, R. (2013). Does sample size matter in qualitative research? A review of qualitative interviews in IS research. Journal of Computer Information Systems,

54, 11-22. doi:10.1080/08874417.2013.11645667

[47] Martinez, M. G. (2015). Solver engagement in knowledge sharing in crowdsourcing communities: Exploring the link to creativity.

Research Policy, 44, 1419-1430. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2015.05.010 [48] Men, L. R., & Hung-Baesecke, C. J. F. (2015). Engaging employees

in China: The impact of communication channels, organizational transparency, and authenticity. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 20, 448-467. doi:10.1108/CCIJ-11-2014-0079 [49] Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2017). Augmenting the sense of

attachment security in group contexts: The effects of a responsive leader and a cohesive group. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 67, 161-175. doi:10.1080/00207284.2016.1260462 [50] Nel, T., Stander, M. W., & Latif, J. (2015). Investigating positive

leadership, psychological empowerment, work engagement and satisfaction with life in a chemical industry. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 41(1), 1-13. doi:10.4102/sajip.v4i1.1243

[51] Nimon, K., Shuck, B., & Zigarmi, D. (2016). Construct overlap between employee engagement and job satisfaction: A function of semantic equivalence? Journal of Happiness Studies, 17, 1149-1171. doi:10.1007/s10902-015-9636-6

[52] Offord, M., Gill, R., & Kendal, J. (2016). Leadership between decks: A synthesis and development of engagement and resistance theories of leadership based on evidence from practice in royal Navy warships.

Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 37, 289-304. doi:10.1108/LODJ-07-2014-0119

[53] Olafsen, A. H., Halvari, H., Forest, J., & Deci, E. L. (2015). Show them the money? The role of pay, managerial need support, and justice in a self‐determination theory model of intrinsic work

motivation. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 56, 447-457. doi:10.1111/sjop.12211

[54] Paillé, P., Chen, Y., Boiral, O., & Jin, J. (2014). The impact of human resource management on environmental performance: An employee-level study. Journal of Business Ethics, 121, 451-466. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1732-0

[55] Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research.

Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42, 533-544. doi:10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y [56] Paulo, R. M., Albuquerque, P. B., Saraiva, M., & Bull, R. (2015). The

enhanced cognitive interview: Testing appropriateness perception,

memory capacity and error estimate relation with report quality.

Applied Cognitive Psychology, 29, 536-543. doi:10.1002/acp.3132 [57] Peng, A. C., Lin, H. E., Schaubroeck, J., McDonough III, E. F., Hu,

B., & Zhang, A. (2016). CEO intellectual stimulation and employee work meaningfulness: The moderating role of organizational context.

Group & Organization Management, 41, 203-231. doi:10.1177/1059601115592982

[58] Petrou, P., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2016). Crafting the change. The role of employee job crafting behaviors for successful organizational change. Journal of Management, 1-27. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/0149206315624961

[59] Popli, S., & Rizvi, I. A. (2016). Drivers of employee engagement: The role of leadership style. Global Business Review, 17, 965-979. doi:10.1177/0972150916645701

[60] Popli, S., & Rizvi, I. A. (2017). Leadership style and service orientation: The catalytic role of employee engagement. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 27, 292-310. doi:10.1108/JSTP-07-2015-0151

[61] Rana, S., Ardichvili, A., & Tkachenko, O. (2014). A theoretical model of the antecedents and outcomes of employee engagement: Dubin's method. Journal of Workplace Learning, 26, 249-266. doi:10.1108/JWL-09-2013-0063

[62] Rao, M. S. (2017). Innovative tools and techniques to ensure effective employee engagement. Industrial and Commercial Training, 49, 127-131. doi:10.1108/ICT-06-2016-0037

[63] Reis, G., Trullen, J., & Story, J. (2016). Perceived organizational culture and engagement: The mediating role of authenticity. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31, 1091-1105. doi:10.1108/JMP-05-201-0178

[64] Reunanen, T., Penttinen, M., & Borgmeier, A. (2017). “Wow-Factors” for boosting business. In Advances in Human Factors, Business Management, Training and Education, 498, 589-600. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-42070-7

[65] Robinson, O. C. (2014). Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: A theoretical and practical guide. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11, 25-41. doi:10.1080/14780887.2013.801543

[66] Rodríguez-Sánchez, A. M., Devloo, T., Rico, R., Salanova, M., & Anseel, F. (2016). What makes creative teams tick? Cohesion, engagement, and performance across creativity tasks. A three-wave study. Group & Organization Management, 1-27. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/1059601116636476

[67] Rucker, M. R. (2017). Workplace wellness strategies for small businesses. International Journal of Workplace Health Management,

10, 55-68. doi:10.1108/IJWHM-07-2016-0054

[68] Saks, A. M., & Gruman, J. A. (2014). What do we really know about employee engagement? Human Resource Development Quarterly, 25, 155-182. doi:10.1002/hrdq.21187

[69] Santiago-Delefosse, M., Gavin, A., Bruchez, C., Roux, P., & Stephen, S. L. (2016). Quality of qualitative research in the health sciences: Analysis of the common criteria present in 58 assessment guidelines by expert users. Social Science & Medicine, 148, 142-151. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.007

[70] Sarti, D. (2014). Job resources as antecedents of engagement at work: Evidence from a long‐term care setting. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 25, 213-237. doi:0.1002/hrdq.21189

[71] Saunders, M. N., & Townsend, K. (2016). Reporting and justifying the number of interview participants in organization and workplace research. British Journal of Management, 27(4), 1-17. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12182

[72] Saxena, V., & Srivastava, R. K. (2015). Impact of employee engagement on employee performance - Case of manufacturing sectors. International Journal of Management Research and Business Strategy, 4(2), 139-174. Retrieved from http://www.ijmrbs.com/ [73] Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2014). A critical review of the job

demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health

(pp. 43-68). doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5640-3_4

[74] Shuck, B., Adelson, J. L., & Reio, T. G. (2016). The employee engagement scale: Initial evidence for construct validity and implications for theory and practice. Human Resource Management,

1-25. Advance online publication. doi:10.1002/hrm.21811

development. Human Resource Development Review, 15, 208-229. doi:10.1177/1534484316643904

[76] Shuck, B., & Reio, T. G. (2011). The employee engagement landscape and HRD: How do we link theory and scholarship to current practice?

Advances in Developing Human Resources, 13, 419-428. doi:10.1177/1523422311431153

[77] Shuck, B., & Reio, T. G. (2014). Employee engagement and well-being a moderation model and implications for practice. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 21, 43-58. doi:10.1177/1548051813494240

[78] Shuck, B., & Rose, K. (2013). Reframing employee engagement within the context of meaning and purpose: Implications for HRD.

Advances in Developing Human Resources, 15, 341-355. doi:10.1177/1523422313503235

[79] Szpunar, K. K., Addis, D. R., McLelland, V. C., & Schacter, D. L. (2013). Memories of the future: New insights into the adaptive value of episodic memory. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 7(47), 1-3. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00047

[80] Taneja, S., Sewell, S. S., & Odom, R. Y. (2015). A culture of employee engagement: A strategic perspective for global managers.

Journal of Business Strategy, 36, 46-56. doi:10.1108/JWL-09-2013-0070

[81] Trépanier, S. G., Fernet, C., Austin, S., Forest, J., & Vallerand, R. J. (2014). Linking job demands and resources to burnout and work engagement: Does passion underlie these differential relationships?

Motivation and Emotion, 38, 353-366. doi:10.1007/s11031-013-9384-z

[82] U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board. (2015). Managing for engagement - Communication connection and courage. Retrieved from http://www.mspb.gov

[83] Ugwu, F. O., Onyishi, I. E., & Rodríguez-Sánchez, A. M. (2014). Linking organizational trust with employee engagement: The role of psychological empowerment. Personnel Review, 43, 377-400. doi:10.1108/PR-11-2012-0198

[84] Vitt, L. A. (2014). Raising employee engagement through workplace financial education. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 141, 67-77. doi:10.1002/ace.20086

[85] Wong, S., & Cooper, P. (2016). Reliability and validity of the explanatory sequential design of mixed methods adopted to explore the influences on online learning in Hong Kong bilingual cyber higher education. International Journal of Cyber Society and Education, 9, 45-66. doi:10.7903/ijcse.1475

[86] Wong, W. P., Hassed, C., Chambers, R., & Coles, J. (2016). The effects of mindfulness on persons with mild cognitive impairment: Protocol for a mixed-methods longitudinal study. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 8(156), 1-15. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2016.00156

[87] Zhu, W., Treviño, L. K., & Zheng, X. (2016). Ethical leaders and their followers: The transmission of moral identity and moral attentiveness.

Business Ethics Quarterly, 26, 95-115. doi:10.1017/beq.2016.11

AUTHORS

First Author – Dr. Janet L. Deskins, DBA, PMP, College of Management and Technology, Walden University,