______________

JUAN CARLOS HUERTA is associate professor of political science at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi. ADOLFO SANTOS is associate professor of political science at the University of Houston-Downtown.

The American Review of Politics, Vol. 27, Summer, 2006: 115-128 ©2006 The American Review of Politics

Latino Representation in the U.S. Congress:

How Much and by Whom?

Juan Carlos Huerta and Adolfo Santos

Research on measuring support for Latino issues in Congress has found that party affiliation is the primary influence on the level of support. The research also demonstrates that under certain scenarios, Latino representatives do provide more substantive Latino representation than do non-Latino representatives. The purpose of this project is to re-evaluate these earlier findings using more recent data in a changed political context. In addition, the project will examine the effects that different types of Democrats have on Latino representation. The findings suggest that when it comes to support for Latino issues, there are differences between the parties, and within the Democratic Party. An unexpected source of Latino representation, members of the Congressional Black Caucus, is also revealed in the findings.

In the summer and fall of 2003, the Republican dominated Texas Legislature was redistricting the U.S. House seats that had previously been redrawn in 2001, rather than waiting until after the 2010 census. The goal of the 2003 redistricting was to redraw the boundaries to elect more Republican U.S. House members (Ratcliffe and Robison 2003). Among the targets of the redistricting were several moderate and conservative white Democrats. A legal challenge against the redistricting alleged that Latino communities were intentionally split so their votes would not help elect Democrats (Rat-cliffe and Robison 2003).1 The concern was that Latino communities would lose representation under the new plan that replaced Democratic representa-tives with Republicans.

Representation and Latinos

Latinos have become the single largest minority group in the United States (12.5% of the population), yet are underrepresented (4%) in the U.S. Congress.2 What does it mean to be underrepresented and does better Latino representation only result from electing more Latinos to Congress? The literature defines representation in one of two general ways—descriptive representation and substantive representation (Hero and Tolbert 1995; Pitkin 1967; Welch and Hibbing 1984).

Descriptive representation occurs when legislative institutions reflect the makeup of the people they represent. Thus, if a group makes up 20 per-cent of a population, then to be appropriately descriptively represented, that group would need to have its members comprise 20 percent of the legislative institution. Thus, in terms of descriptive representation, Latinos, women and other minority groups are underrepresented (Swain 1993; Vigil 1984; Vigil 1994; Welch and Hibbing 1984).3 More Latino members of Congress would then lead to more descriptive representation for Latinos.

However, does the presence of Latinos on representative bodies mean that they will provide representation for Latinos? This leads to the concept of substantive representation, which is “acting for others” and refers to the quality of the representation (Pitkin 1967). A Latino representative may not actually represent the interests of Latinos, resulting in poor substantive representation. Alternatively, a non-Latino representative would not provide descriptive representation, yet could provide strong substantive representa-tion. A central question in the research on Latino representation asks if Latino representatives provide better “Latino representation,” that is do the Latino members of the U.S. House of Representatives represent Latino constituents better than non-Latino representatives (Hero and Tolbert 1995; Kerr and Miller 1997; Santos 2001; Santos and Huerta 2001)? Research on African American substantive representation has found that members of the Congressional Black Caucus are critical to passing legislation that benefits minorities (Menifield and Jones 2001).

Latinos) pack minorities into minority districts and create “whiter” Republi-can districts, leading to less substantive minority and Latino representation (Brace, Grofman, and Handley 1987; Overby and Cosgrove 1996)?

The potential loss of Latino substantive representation from majority-minority districts is important because of the two types of substantive repre-sentation—dyadic and collective representation (Weissberg 1978). Dyadic representation, also known as “direct substantive representation” (Hero and Tolbert 1995), occurs when the representatives’ voting patterns in the House are in alignment with the preferences of his/her constituents. Collective, or “indirect substantive representation,” occurs when constituents are not “represented” by their own representative, but rather one from another district. Thus, Latinos may live in the district of a member of Congress who ignores the concerns of those Latinos, but there are other members of Con-gress who will represent their interests. Furthermore, political parties can also contribute to collective, indirect representation (Hurley 1989), and this can be important for Latino representation if Democrats are indeed more likely to support Latino issues.

Do Latino representatives provide better representation (direct substan-tive) for Latinos? The evidence is mixed, with some finding that party affili-ation is a better predictor of support for Latino issues than whether or not the representative is Latino (Hero and Tolbert 1995; Kerr and Miller 1997). This then suggests that descriptive Latino representation offers no advantage over non-Latino substantive representation. However, there is evidence that on some issues, Latino representatives do provide better representation than non-Latino representatives (Santos and Huerta 2001). Also, some studies have found that the percentage of Latinos in the district has an impact on non-Latino Democrats, indicating that representatives do respond to the make-up of their districts (Santos 2001; Santos and Huerta 2001).

The literature is clear that party has a major impact. What the literature has not yet addressed is how does the ideology of Democratic representa-tives affect their support of Latino issues, and is there a difference in Latino representation between more conservative Democrats and Republicans? Are representatives more responsive to Latino issues if they have a larger popu-lation of Latinos in their district? The paper will examine and compare sup-port for Latino issues from different types of Democrats and help to reach a deeper understanding of how much Latino representation is affected by party affiliation and the ideology of Democratic representatives. Furthermore, this research examines Latino politics in an era with a Republican president, a divided Congress, and in a post September 11 environment—an environ-ment that may lead to changes in representation from the earlier studies.

● Are Latinos more likely to support Latino issues than non-Latino Democrats?

● Does the ideology of the Democratic representatives influence their support?

● Do moderate to conservative Democrats provide more substantive Latino representation than do Republicans?

● How much influence does the percent of the district population that is Latino (Hispanic) have on support for Latino issues?

● How does membership in the Black Caucus affect Latino representa-tion?

Thus, the research will add to the understanding of Latino representa-tion through an examinarepresenta-tion of variarepresenta-tions of representarepresenta-tion by different cate-gories of Democrats, and in comparison to support from Republicans.

Research Design

The unit of analysis for this study is the individual member of the House of Representatives from the 107th Congress (2001-2002).

Dependent Variable

Substantive representation for Latinos is defined in this study as sup-port on Congressional votes for Latino issues. Consistent with existing literature, a “Congressional Scorecard” developed by the National Hispanic Leadership Agenda (NHLA) is used as the dependent variable to measure substantive Latino representation.

The NHLA issues an annual Congressional Scorecard rating how mem-bers of the House of Representatives vote on issues affecting the “social, economic, and political advancement and quality of life of Hispanic Ameri-cans.”4 The votes included in the scorecard are amendments to bills, votes on final passage of bills, and motions. There are a total of eighteen votes in the scorecard, chosen for their importance to the Latino community in terms of substance and symbolism; if the House member was informed of the NHLA’s position on the bill; and if there was a consensus among members of the NHLA on the importance of the vote to the Latino community. The scorecard “score” is the percent of pro NHLA votes. Higher scores on the scorecard (which ranges from 0-100) indicate more support for Latino issues—more substantive representation. Additional information about the votes in the NHLA Congressional Scorecard is available in the Appendix.

Latino community. Scorecards are not complete measures of substantive representation; their shortcomings are well noted (Canon 1999). They do not measure other important aspects of substantive representation such as the political skill of a member of Congress in passing legislation, sponsoring bills, casework, or the negotiation and bargaining that occurs in Congress. Nonetheless, they do provide a valuable, though incomplete measure of substantive representation. To simply dismiss them is akin to dismissing survey data because of measurement error.

Independent Variables

Whether or not the member of the U.S. House is Latino is included as an independent variable. Latino members of the House are coded as “1” and non-Latinos “0.” An issue that has not received much attention is the support of the Black Congressional Caucus. Members of the Black Caucus are coded as “1” and non-members “0.” If descriptive representation leads to more substantive representation (direct substantive), then Latino representatives are expected to be the most supportive of Latino issues. Black Caucus mem-bers of Congress are expected to be supportive, but not more supportive than Latinos (indirect substantive), because many of the votes in the scorecard likely impact African Americans. Additionally, the percent Latino (His-panic) for the 107th Congress districts is available from the 2000 Census and is included. Members of the House are expected to be more supportive of Latino issues as the percent Latino of the district increases.

The party affiliation and ideology of the Democratic members is also included in the analysis. Prior research has established that Democratic affiliation is a major contributor to Latino representation (Hero and Tolbert 1995; Kerr and Miller 1997). What has not yet been fully established is how strongly moderate to conservative Democratic members support Latino issues. The ideology of Democrats is measured by membership in the Blue Dog Coalition (BDC)—a group of conservative to moderate Democrats.5

Members of the BDC are coded as “1” and all others as “0.” Another dichotomous variable is created for non-BDC Democrats—Democrats who are not members of the BDC. Non-BDC Democrats are coded as “1” and all others as “0.” Variables for BDC Democrats and non-BDC Democrats are included so the impact of each ideological category of Democrats can be assessed. The expectation is that both the non-BDC Democrats and BDC Democrats will be more supportive of Latino issues than Republicans. Addi-tionally, the BDC Democrats, because they are more conservative, are expected to be less supportive of Latino issues than non-BDC Democrats.

The variables will be analyzed using ordinary least squares (OLS) mul-tiple regression. The effect of Republican affiliation on Latino substantive representation is measured by the constant.

Findings

The first model examines the impact of Latino, African American, BDC, non-BDC, and percent Hispanic on Latino representation. The find-ings from the OLS analysis of these variables on Latino support are pre-sented in the Model 1 column of Table 1.

The results indicate that both BDC and non-BDC Democrats are much more supportive of Latino issues than Republicans (the constant reveals the low support from Republicans).6 Furthermore, as expected, the non-BDC Democrats are more supportive than the BDC Democrats. Unexpectedly, the coefficient for African American representatives (11.68) is larger than the Latino representative coefficient (10.70). The findings from the Black Caucus and Latino items indicate how much more “being” a Latino or Afri-can AmeriAfri-can representative adds to representation, and points to robust indirect substantive representation from Black Caucus members and direct substantive from Latino members. Latino and African American representa-tives do have a positive impact on representation.

Interestingly, the percent Latino of the district does not have an inde-pendent effect. A likely explanation is because all of the Latino representa-tives are from districts that have at least 47 percent Latino populations. The mean percent Latino in the districts represented by Latino representatives is 66 percent versus 10 percent for the non-Latino representatives. Perhaps, the Latino variable and percent Latino are too closely related for both to be in-cluded in the model. Will dropping percent Latino from the model improve the performance of the Latino variable?

Table 1. Unstandardized Coefficient Estimates for Latino Substantive Representation, 107th Congress

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4

Variable B B B B

Constant 12.35** 12.65** 11.60** 12.28**

Latino 10.70** 12.65**

Black Caucus 11.68** 11.78** 10.95** 11.50** Blue Dog Democrat 43.68** 43.64** 44.19** 42.30** Non-Blue Dog Democrat 60.78 60.88** 60.92** 60.92** Percent Latino .04 .13** .05

N 432 432 432 413

Adjusted R-Square .91 .91 .90 .90

SEE 10.04 10.03 10.14 10.13

**.01 significance

A consequence of dropping the percent Latino item is the impact of percent Latino on non-Latino representatives is omitted. To assess the im-pact of percent Latino, the Latino item is dropped and percent Latino in-cluded in Model 3. Model 3’s findings (in the Model 3 column of Table 1) demonstrate that percent Latino does have a significant and positive effect on Latino substantive representation (with the Latino item excluded). The impact of Latino representatives is indirectly measured because all of the Latino representatives have large Latino constituencies. This finding sug-gests a larger percent Latino in a district will lead to more substantive representation.

However, is this finding being driven by Latino representatives? What will happen to Model 3 if Latino representatives are excluded from the model? Model 4 repeats Model 3 but excludes the 19 Latino representatives. The Model 4 column in Table 1 reveals that removing the 19 Latino repre-sentatives from the analysis, percent Latino is insignificant. Thus, the evi-dence finds that an increasing percentage of Latinos in a district (excluding Latino representatives) is unrelated to more support for Latino issues.

Figure 1. NHLA Scorecard and Percent Latino in District by Party Categories, 107th Congress

Percen t Lat ino in Dis t rict

1 0 0 8 0

6 0 4 0

2 0 0

1 0 0

8 0

6 0

4 0

2 0

0

No n - Blu e Do g De mo cr at

Blu e Do g De mo cr at

Rep u b lican

Percent Latino in District

Note: Latino representatives are excluded from the analysis

Republican, BDC Democrat, or non-BDC Democrat is presented in Figure 1. The scatterplot excludes the 19 Latino representatives.

The scatterplot findings from Figure 1 indicate non-Blue Dog Demo-crats are supportive of Latino issues regardless of the percent Latino in the district. The same general pattern applies for the BDC Democrats, although they are less supportive overall than the non-BDC Democrats. Thus, both types of non-Latino Democrats are supportive of Latino issues whether they have small or large percentages of Latinos in their districts. The same pattern applies to non-Latino Republicans—they are less supportive of Latino issues and the support is unrelated to the percent Latino in the district. Non-Latino Republicans with 40 percent Latino in their districts are no more supportive of Latino issues than non-Latino Republicans with small percentages of Latinos in their districts.

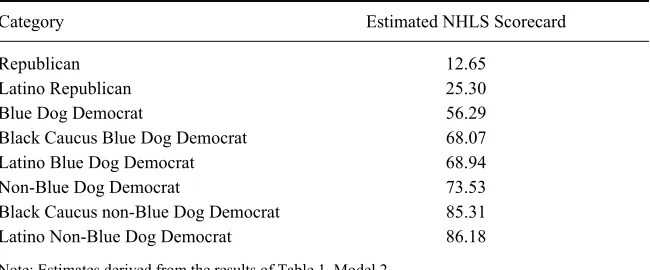

Table 2. Estimated NHLS Scorecard Scores

for Different Categories of Representatives, 107th Congress

Category Estimated NHLS Scorecard

Republican 12.65 Latino Republican 25.30

Blue Dog Democrat 56.29 Black Caucus Blue Dog Democrat 68.07 Latino Blue Dog Democrat 68.94 Non-Blue Dog Democrat 73.53 Black Caucus non-Blue Dog Democrat 85.31 Latino Non-Blue Dog Democrat 86.18

Note: Estimates derived from the results of Table 1, Model 2.

the constant, non-BDC Democrat, and Latino item are summed. The esti-mates are presented in Table 2.

The findings in Table 2 are ranked from least to most supportive. The least supportive category for substantive Latino representation is Republican and the most supportive is non-BDC Latino Democrat (direct substantive). The most supportive category of Republican is Latino Republican. However, that category estimate is much lower than the lowest Democrat category— BDC Democrat. Interestingly, the results indicate a higher estimate for non-BDC Democrat than Latino non-BDC Democrat (there are 3 non-BDC Latino Demo-crats). The results from Table 2 demonstrate that Latino representatives do improve Latino representation, especially when considering the role of party and ideology.

Discussion

Who is more likely to support Latino issues, and thus provide better substantive representation for Latinos? The answers to the research ques-tions illustrate the findings.

● Are Latinos more likely to support Latino issues than non-Latinos? Yes, the research found that the Latino item has a positive impact (12.65 more scorecard points) on support for Latino issues. This indi-cates that being a Latino representative “adds” support.

Coalition Democrats. The BDC Democrats are much more likely to support Latino issues than Republicans. Interestingly, according to Table 2, non-BDC non-Latino Democratic representatives are more supportive of Latino issues than BDC Latino Democrats. Thus, the ideology of the Democrats does make a difference.

● How much more representation do different kinds of Democrats pro-vide than Republicans? Across the categories, Democrats are much more supportive of Latino issues than Republicans. Replacing a BDC Democrat with a Republican, even a Latino Republican, will likely lead to a decline in Latino substantive representation.

● How much influence does the percent of the district population that is Latino (Hispanic) have on support for Latino issues? A larger percent of Latinos in a district leads to increased Latino representation because the district is likely to have a Latino representative, and Latino repre-sentatives are more likely to support Latino issues. The assumption that a non-Latino representative will become more supportive of Latino issues because they have a larger percent Latino in their district is not supported. This is not to suggest that a non-Latino representative will do a poor job representing Latino issues; rather, it is because many non-Latino representatives with small percentages of non-Latinos in their dis-tricts are as supportive of Latino issues as non-Latinos with large Latino percentages. Furthermore, most of the non-Latino representa-tives with larger Latino populations are Democrats—the more sup-portive party. Additionally, non-Latino Republican support for Latino issues is unrelated to the percent Latino in the district. Thus, a larger percent of Latinos in a non-Latino Republican district does not lead to more support for Latino issues.

The evidence indicates Latino representatives do provide direct-substantive representation for Latinos. However, Latino Republicans do not provide as much substantive representation for Latinos as any category of Democrats. According to the evidence, a non-Latino Democrat better repre-sents Latinos than a Latino Republican. Descriptive Latino representation counts, but primarily for Democratic representatives. Furthermore, the per-cent Latino in the district matters because as the perper-centage increases, it is likely to lead to the election of a Latino representative or a Democrat. Sub-stantive representation by non-Latino representatives is unrelated to the percent Latino in the district.

dependent variable are based on civil rights, education, economic mobility and health. These issues may also benefit the constituents of African Ameri-can representatives. The NHLA scorecard is simply a tally of “pro-Hispanic” votes and it is possible that someone can vote pro-Hispanic without that being the intent.

Conclusion

The introduction discussed redistricting in Texas and speculated on how that would affect Latino substantive representation. The evidence is clear that redistricting that produces more Republican districts at the expense of white Democrats will lead to a decline in Latino substantive representa-tion. Thus, the redistricting in Texas can be expected to lead to a decline in overall Latino substantive representation.

The research also confirms the importance of party for Latino represen-tation. Prior studies of Latino representation were conducted in different political contexts (different party control of the Congress and presidency). The Congress under investigation had a House controlled by the Republi-cans, and evenly divided Senate that switched from Republican to Demo-cratic control, and a Republican president. Also, after 9/11 terrorism and the build up to war with Iraq became national priorities. The political context is different from prior Latino representation studies, yet the findings reaffirm the importance of party.

Latino descriptive representation does make a difference. Latino repre-sentatives do provide better representation than their ideological and partisan cohorts. Latinos are much better off with any type of Democrat and espe-cially a Latino or Black Democrat. This leads to a question for future re-search—do Latino Democrats provide indirect substantive African American representation comparable to the indirect substantive representation the Black caucus provides for Latinos?

APPENDIX

Specifically, the scorecards examine votes on civil rights, education, economic mobility and health, and telecommunications. A short description of the bill is included. On most votes, the NHLA position is to vote “no.”

Civil Rights

APPENDIX (continued)

2. Motion to Suspend the Rules and Pass [offered by Representative Bill Thomas (R– CA)] the Customs Border Security Act of 2001, H.R. 3129. Legal immunity for Customs officials. (Roll No. 478), December 6, 2001. (NHLA Position: NO)

3. Motion to Recommit with Instructions [offered by Representative Robert Menendez (D–NJ)] the Help America Vote Act of 2001, H.R. 3295. Protections against voting rights violations. (Roll No. 488), December 12, 2001. (NHLA Position: YES)

4. The Customs Border Security Act of 2001, H.R. 3129—Sponsored by Representative Phillip M. Crane (R–IL). Extending law enforcement powers to Immigration and Naturalization Service. (Roll No. 193), May 22, 2002. (NHLA Position: NO)

5. Agreeing to the Conference Report for the Help America Vote Act of 2001, H.R. 3295—Sponsored by Representative Robert Ney (R–OH). Contains provisions that could potentially disenfranchise Latino voters. (Roll No. 462), October 10, 2002. (NHLA Position: NO)

6. Sober Borders Act, H.R. 2155—Sponsored by Representative Jeff Flake (R–AZ). A bill to make it a federal crime to operate a motor vehicle under the influence of drugs or alcohol at a land port of entry. Bill could target Latinos and it extends law enforce-ment powers to Immigration and Naturalization Service unrelated to immigration. Motion passed 296-94, (Roll No. 465), October 16, 2002. (NHLA Position: NO)

Education

1. The No Child Left Behind Act, H.R. 1—Sponsored by Representative John A. Boehner (R–OH). Contains provisions that could deny Hispanic children opportunities to succeed. (Roll No. 145), May 23, 2001. (NHLA Position: NO)

2. Tiberi Amendment, H. AMDT. 51, to H.R. 1—Sponsored by Representative Patrick J. Tiberi (R–OH). Consolidation of education grants. Could lead to less accountability in how money is used to assist at-risk children. (Roll No. 132), May 22, 2001. (NHLA Position: NO)

3. Norwood Amendment, H.AMDT. 55, to H.R. 1—Sponsored by Representative Charlie Norwood (R–GA). Would allow schools to deny all education services to students with disabilities expelled for certain actions. (Roll No.138), May 22, 2001. (NHLA Position: NO)

4. Cox Amendment, H. AMDT. 69, to H.R. 1—Sponsored by Representative Chris-topher Cox (R–CA). Sought to limit the aggregate increase in authorization of appropriations for fiscal year 2002 to 11.5 percent. Would have limited increases for education funding. (Roll No. 143), May 23, 2001. (NHLA Position: NO)

5. Congressional Budget Resolution, H. Con. Res. 353 (Sponsored by Representative Jim Nussle (R–IA). The Budget Resolution freezes or cuts education programs affecting Latino students. (Roll No. 79), March 20, 2002. (NHLA Position: NO)

Economic Mobility and Health

1. Budget Resolution FY 2002 Appropriations, H. Con. Res. 83 (Sponsored by Repre-sentative Jim Nussle (R–IA). Leaves many programs and issues important to Latinos underfunded including bilingual education, adult education and training, housing and community development, and health care programs. Bill passed 221-207, (Roll No. 104), May 9, 2001. (NHLA Position: NO)

APPENDIX (continued)

bill is skewed with tax relief for wealthier individuals and not low-income Latino families. Bill passed 240-154, (Roll No.149), May 26, 2001. (NHLA Position: NO) 3. Economic Security and Recovery Act of 2001, H.R. 3090—Sponsored by

Repre-sentative Bill Thomas (R–CA). The bill provides vast tax break for wealthy indi-viduals and corporations with little assistance for working families. Bill passed 216-214, (Roll No. 404), October 24, 2001. (NHLA Position: NO)

4. Norwood Amendment, H.AMDT. 303, to the Patients’ Bill of Rights, H.R. 2563— Sponsored by Representative Charlie Norwood (R–GA). Would preempt stronger state laws regulating HMOs. (Roll No. 329), August 2, 2001. (NHLA Position: NO) 5. The Personal Responsibility, Work, and Family Promotion Act, H.R. 4737—

Sponsored by Representative Deborah Pryce (R–OH). Increases work requirement for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families while not providing resources for childcare and education. (Roll No. 170), May 16, 2002. (NHLA Position: NO)

6. Motion to Instruct Conferees [offered by Joe Baca (D–CA)] for the Farm Security Act, H.R. 2646—Sponsored by Larry Combest (R–TX). The bill seeks to restore food stamps to many legal immigrants. (Roll No. 106), April 23, 2002. (NHLA Position: YES)

Telecommunications

The Internet Freedom and Broadband Deployment Act, H.R. 1542—Sponsored by Representative W.J. (Billy) Tauzin (R–LA) and Representative John Dingell (D–MI). Stimulating broadband internet deployment. (Roll No. 45), February 27, 2002. (NHLA Position: YES)

NOTES

1There is a difference of opinion about the preferred use of Latino and Hispanic.

The study will use the term Latino when referring to Hispanics.

2Population Profile of the United States: 2000 (Internet Release) 2003 [cited.

Avail-able from http://www.census.gov/population/www/pop-profile/profile2000.html. There were 19 Latino members of the U.S. House or Representatives in the 107th Congress.

3A contributing factor to the underrepresentation of Latinos is that significant

por-tions of the Latino population are not U.S. citizens, and thus ineligible to vote.

4National Hispanic Leadership Agenda Congressional Scorecard 107th Congress,

First and Second Session: National Hispanic Leadership Agenda

5The list of members of the Blue Dog Coalition was difficult to find. A Lexis/Nexis

6Any Independents in the House are coded with the Republicans.

7This procedure is straightforward because all of the independent variables in

Model 2, Table 1 are dummy variables.

REFERENCES

Brace, Kimball, Bernard Grofman, and Lisa Handley. 1987. Does Redistricting Aimed to Help Blacks Necessarily Help Republicans? The Journal of Politics 49:169-185. Butler, David, and Bruce E. Cain. 1992. Congressional Redistricting: Comparative and

Theoretical Perspectives. New York: Macmillan.

Canon, David T. 1999. Race, Redistricting, and Representation: The Unintended Conse-quences of Black Majority Districts. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Hero, Rodney E., and Caroline J. Tolbert. 1955. Latinos and Substantive Representation

in the U.S. House of Representatives: Direct, Indirect, or Nonexistent? American Journal of Political Science 39:640-652.

Hurley, Patricia A. 1989. Partisan Representation and the Failure of Realignment in the 1980s. American Journal of Political Science 33:240-261.

Jackson, John E., and John W. Kingdon. 1992. Ideology, Interest Group Scores, and Legislative Votes. American Journal of Political Science 36(3):805-823.

Kerr, Brinck, and Will Miller. 1997. Latino Representation, It’s Direct and Indirect. American Journal of Political Science 41:1066-1071.

Overby, L. Marvin, and Kenneth M. Cosgrove. 1996. Unintended Consequences? Racial Redistricting and the Representation of Minority Interests. Journal of Politics 58:540-550.

Pitkin, Hanna Fenichel. 1967. The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Ratcliffe, R.G., and Clay Robison. 2003. Remap Will Turn Away Minorities, Judges Told. The Houston Cronicle, December 12, p. 37.

Santos, Adolfo. 2001. Substantive Representation for Hispanics: Explaining Congres-sional Support for Hispanic Issues. Harvard Journal of Hispanic Policy 13:45-65. Santos, Adolfo, and Juan Carlos Huerta. 2001. An Analysis of Descriptive and

Substan-tive Latino Representation in Congress. In Representation of Minority Groups in the U.S.: Implications for the Twenty-first Century, ed. C. Menifield. Lanham, MD: Austin & Winfield.

Swain, Carol M. 1993. Black Faces, Black Interests: The Representation of African Americans in Congress. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Vigil, Maurilio E. 1984. Hispanics Gain Seats in the 98th Congress after Reapportion-ment. International Social Science Review 59:20-30.

Vigil, Maurilio E. 1994. Hispanics in the 103rd Congress: The 1990 Census, Reappor-tionment, Redistricting, and the 1992 Elections. Latino Studies Journal 5:40-76. Weissberg, Robert. 1978. Collective vs. Dyadic Representation in Congress. American

Political Science Review 72:535-536.