P

IOTRW

ÓJCICKI1, 2, M

ARIUSZW

YSOCKI2Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction

with Autologous Tissue – Free Flaps. Part II

Rekonstrukcje piersi po mastektomii tkankami własnymi

– płaty wolne. Część II

1Department of Plastic Surgery, Wroclaw Medical University, Poland

2Department of Plastic Surgery, Specialist Medical Center, Polanica Zdroj, Poland

Adv Clin Exp Med 2009, 18, 6, 657–667 ISSN 1230–025X

REVIEWS

© Copyright by Wroclaw Medical University

Abstract

Breast cancer is the most common tumor occurring in women. Loss of a breast is a profound traumatic experience. Since the breast is a symbol of femininity, beauty, and motherhood, mastectomy can result in serious disorders of psychological and aesthetic character. Advances in microsurgical techniques facilitated the development of various methods indispensable for performing even the most extensive reconstructions with achievement of a good final result, opening the possibility for effective rehabilitation and a return to normal psychosocial functioning. Postmastectomy breast reconstruction with free flaps has become the standard course of action, and the choice of flaps assures selection of the best method available for each patient. This paper is a review of the most important free tissue flaps used in postmastectomy breast reconstruction, including the free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM), the deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP), the paraumbilical perforator (PUP), the superior and inferior gluteal, the Rubens, and the thigh lateral transverse and anterolateral thigh flaps (Adv Clin Exp Med 2009, 18, 6, 657–667).

Key words:breast reconstruction, free flaps, breast cancer.

Streszczenie

Rak sutka jest najczęstszym nowotworem u kobiet. Utrata piersi jest tragicznym wydarzeniem wywołującym głęboki uraz psychiczny. Pierś jest symbolem kobiecości, urody oraz macierzyństwa, dlatego mastektomia prowadzi do zaburzeń natury psychicznej i estetycznej. Rozwój technik mikrochirurgicznych pozwolił na opra− cowanie różnych metod umożliwiających wykonanie nawet najbardziej rozległych rekonstrukcji z końcowym dobrym wynikiem, co daje szansę na skuteczną rehabilitację i powrót do normalnego funkcjonowania psy− chospołecznego. Obecnie rekonstrukcje piersi po mastektomii płatami wolnym stały się standardowym postępowaniem, a wybór między poszczególnymi płatami zapewnia dobór najlepszej metody dla każdej pacjentki. W artykule opisano najważniejsze wolne płaty tkankowe stosowane w mikrochirurgicznej rekonstrukcji piersi u kobiet po mastektomii. Omówiono wolny płat skórno−mięśniowy z mięśnia prostego brzucha, perforatorowy płat DIEP, płat oparty na perforatorze okołopępkowym, płaty pośladkowe górny i dolny, płat Rubensa, a także płat boczny poprzeczny uda i płat przednioboczny uda (Adv Clin Exp Med 2009, 18, 6, 657–667).

Słowa kluczowe:rekonstrukcje piersi, płaty wolne, rak piersi.

The major factors conditioning the selection of a breast reconstruction method are the extent of mastectomy and the training of the surgical team. The progress that has been made in the diagnostics and treatment of breast cancer have contributed to a reduction of tissue resection. Breast reconstruc− tive operations may be divided into two main cat− egories: procedures using preserved tissues and

latissimus dorsi flap or the TRAM flap. Although the risk of flap loss is rather low, it may come to disorders in blood flow as a result of pedicle fold− ing or compression. Harvesting a TRAM pedicled flap is burdened with the risk of abdominal hernia; moreover, the transfer and positioning of a vascu− lar pedicle can influence the treatment result. Using a latissimus dorsi flap generally requires the use of a breast prosthesis. Postmastectomy breast reconstruction with free flaps has become the stan− dard course of action, and the choice of flaps assures the selection of the best method for each woman.

Selection of the Operating

Technique

A reconstructive operation must be preceded by an analysis of the numerous factors which will facilitate qualification for a specific reconstructive procedure. An accurate evaluation of the woman’s expectations is extremely important. In extreme cases it may turn out that the woman is more will− ing to accept the lack of a breast than to approve deformation of the donor site after flap harvesting.

The main requirement to be qualified for an operation is good physical condition. A high oper− ational risk may indicate the necessity to delay the operation or even abort it. When selecting the technique itself, determining the specific flap must take into consideration body build and the accessi− bility of tissues in particular body regions that

cannot be affected with disease. The experience of the surgical team as well as the woman’s sugges− tions are equally relevant. Patients with unrealistic expectations, or with a tendency for extensive keloidal scars, ought to be excluded from opera− tions [2]. Older women (> 65 years) are qualified for less burdensome reconstructive operations with alloplastic implants. Some authors [3] under− line the fact that advanced age is not a decisive factor in such qualification, since it was demon− strated that older women exhibit complications more frequently after implant use than after recon− structions with autologous tissues. As a conse− quence of these complications, one is faced with the necessity to remove the implant in approxi− mately 42% of patients [3].

Due to the simpler operating technique, allo− plastic implants are readily used in breast recon− structive procedures. Their advantages are no additional scars, no demand for longer hospitaliza− tion, and simplicity of the procedure. Five years following the reconstructive operation, about 30% of patients require correction of capsular contrac− ture or implant transfer or damage [14]. Hence knowledge of the advantages and disadvantages of reconstructive procedures allows individual selec− tion of the best possible method for a woman (Table 1).

Microsurgical breast reconstructions have been performed since the beginning of the 1980s. The most frequently chosen methods are the free TRAM flap and the DIEP flap [5–8]. The skin color is similar to breast skin and an adequate amount of delicate elastic skin helps to obtain

Table 1.The factors considered in selecting an operating method

Tabela 1. Zestawienie czynników uwzględnianych w wyborze metody operacyjnej

Factors Autologous tissue Alloplastic implants

(Czynniki) (Tkanki własne) (Wszczepy alloplastyczne)

Result persistence (Trwałość wyniku) +

Young age (Młody wiek) + +/−

Primary reconstruction (Pierwotna rekonstrukcja) +

Simplicity of procedure (Prostota zabiegu) +

Complication risk (Ryzyko powikłań) +/− +

Secondary complications: scars, look of skin patch +

(Wtórne zniekształcenia: blizny, obraz łaty skórnej)

Secondary procedures (Wtórne zabiegi) + +/−

Operation of second breast (Operacja drugiej piersi) ±

General health condition (Ogólny stan zdrowia) +

Post−reconstructive radiotherapy (Radioterapia porekonstrukcyjna) + +/−

a symmetric breast with suitable volume and pro− jection. In the opinion of many authors, the treat− ment result is not only better owing to reconstruc− tion with implant use, but almost constant in long− term evaluation [9, 10].

In women with contradictions for breast reconstruction with abdominal wall tissue, it is suggested to use the conventional (LD) or extend− ed (ELD) latissimus dorsi flap. Some authors [2], depending on the volume of adiposal tissue and skin quality. use the ELD flap and superior gluteal artery perforator flap interchangeably. As the gluteal region always provides adequate tissue volume for breast reconstruction, it can be consid− ered the exclusive donor site especially in slim patients [11]. Flaps from the thigh or the Rubens flap are alternative methods which find application solely in specific cases of selected patients whose body build allows their application.

Free Flaps

Free Transverse Rectus

Abdominis Myocutaneous Flap

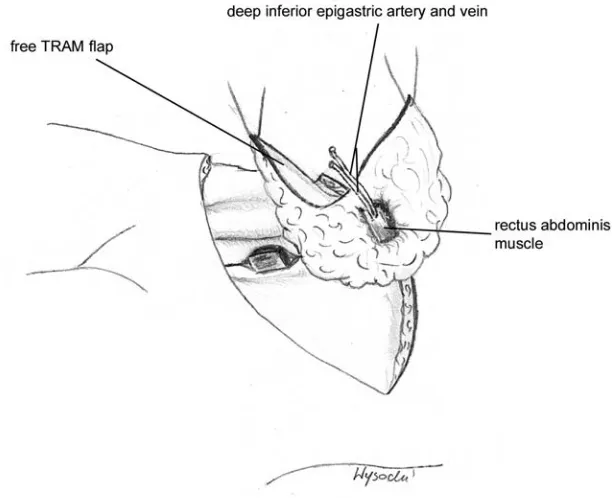

The free flap was introduced by Hölmstrom in 1979 [12] and the first study of consecutive results was published in 1989 [7]. The pedicle consists of the inferior epigastric vessels, the dominant ves− sels supplying the abdominal walls and providing good hemodynamic conditions in both flap zones III and IV (Fig. 1).

The main recipient vessels for the free TRAM flap are the thoracodorsal vessels and internal

mammary vessels. In immediate reconstructions it is suggested to use thoracodorsal vessels prepared during mastectomy [8, 13]. However, there are instances when there is a disproportion between the diameters of the recipient and donor vessels, particularly involving veins that may hinder anas− tomosis [14]. Moreover, in about 40% of cases a short pedicle imposes the application of a venous graft [15]. Internal mammary vessels are proposed in delayed procedures [13]. The pedicle length as a rule suffices for proper flap placement, but the preparation of these vessels requires the removal of the third rib cartilage and anastomosis is ham− pered by respiratory movements [14]. Some authors [14] also suggest, particularly in immedi− ate reconstruction, using the circumflex scapular vessels as recipient vessels.

The free TRAM flap contains a marginal frag− ment of the rectus abdominis muscle and its ante− rior rectus sheath just beneath the skin island. To minimize damage to the abdominal wall, so−called muscle−sparing techniques were introduced based on harvesting an as small as possible fragment of muscle protecting the vascular pedicle. In this manner one can save the lateral, or lateral and medial, part of the belly, dissecting only a 2 ×2 cm muscle fragment [16].

Contradictions to reconstruction with the TRAM flap are the following serious systematic disorders: artery hypertension, diabetes, and autoimmunological diseases. The incidence of complications is considerably higher in obese patients (BMI > 30, 39.1%) than in women with normal body weight (BMI < 25, 20.4%) [17]. Cigarette smoking is a relative contradiction. In the case of active smokers it is advised to quit

Fig. 1. Free transverse rectus abdominis myocuta− neous flap (free TRAM flap)

smoking at least 3–4 to 6 weeks prior to the oper− ation, which improves peripheral circulation and had complication rates similar to those of non− smokers [18, 19]. Despite the described successful reconstructions using abdominal wall tissue in patients who had prior abdominoplasty [20, 21], it is believed that this type of reconstruction ought to be avoided due to the risk of complications.

The complications of free TRAM flap surgery include ischemic complications of the mastectomy skin flap and, primarily, the TRAM flap blood supply. Total flap necrosis occurs as a result of flow disorders through the microvascular anasto− mosis. In the case of pedicled flaps, necrosis appears very seldom and is most often induced by prior cholecystectomy, small diameters of superior epigastric vessels, or excessive pedicle folding or tension. Nevertheless, because of the indirect blood supply of the skin island in pedicled flaps, delayed healing, a consequence of partial flap necrosis and adipose tissue necrosis, appears more frequently (Table 2). More frequent complications in smokers, obese patients, and those who under− went radiotherapy [32] may be diminished by using an additional vascular pedicle or delayed flaps. In the case of harvesting large flaps or in the presence of median abdominal scars, it is suggest− ed to create an additional source of blood supply of tissues contralateral to the pedicle with the so− called “piggyback” technique resting on the junc− tion of the distal end of the inferior epigastric artery with the contralateral paraumbilical perfora− tor [33].

Complications at the donor site can be divided into aesthetic and functional ones. They involve hematoma, seroma, partial necrosis of the abdom− inal flap, abnormalities in wall contour caused by their impairment without fascia damage, bulge of the abdominal region, and hernia. The incidence of these complications is between 0−44%. The most common is abdominal wall weakness in the inferi− or abdominal region [7, 15, 26, 30, 34–42]. The greatest destruction of the abdominal walls

appears after harvesting traditional single and dou− ble pedicled flaps [38] and is the result of harvest− ing the rectus abdominis muscle and its anterior sheath. Extensive abdominal wall preparation increases the risk of necrosis especially in smok− ing patients [2], whereas the presence of a pedicle causes bulging in the epigastric region [36, 37].

Due to the possibility of creating a hernia, it is equally important to repair the abdominal wall in a solid and secure manner and reconstruct the anatomical relations after TRAM flap harvesting, so as to reconstruct a shapely breast. When har− vesting a flap with the muscle−sparing technique, a two−layer closure without tension of the anterior sheath and oblique fascia, the use of synthetic mesh material may considerably reduce complica− tions [2, 36–39].

Deep Inferior Epigastric

Perforator Flap

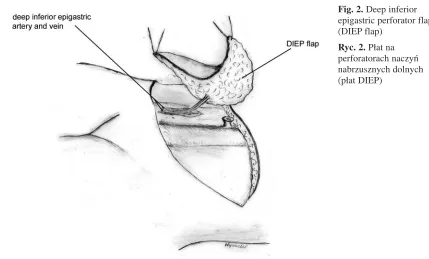

The DIEP flap is harvested without the rectus abdominis muscle and does not contain the anteri− or rectus sheath [16, 41, 43] (Fig. 2). Only a small incision of the anterior sheath and muscle dissec− tion during preparation of the perforators and infe− rior epigastric vessels results in very rare rates of hernia. The skin island is supplied by one to three perforators [16, 44] that ensure a blood supply that is no less satisfactory than in the free TRAM flap [16, 31, 43, 44]. Venous congestion occurs more commonly (52% of patients), mainly involving zone IV [31]. It is not recommended to perform reconstruction with a DIEP flap in cases where the volume of the reconstructed breast exceeds 1000

cm3or when it is required to use over 70% of the

maximum size flap [16, 43]. An essential element is the intraoperatively evaluated quality of the per− forators and superficial inferior epigastric vein. Presence of a dominant artery perforator with a minimum diameter of 1–1.5 mm facilitates the use of a DIEP flap, whereas in other cases it is rec− ommended to convert to a muscle−sparing free

Table 2.Vascular complications in patients with TRAM flap reconstruction (according to [5, 15–19, 22–31])

Tabela 2.Powikłania niedokrwienne w płatach TRAM (wg 5, 15–19, 22–31)

TRAM flap Complications (Powikłania) %

(Płat TRAM) Partial fat necrosis Partial flap necrosis Total flap necrosis (Częściowa martwica (Częściowa martwica płata) (Całkowita martwica płata) tkanki tłuszczowej)

Pedicled 7–26.9 5–13 0.3–3

(Uszypułowany)

Free 0–12.9 0–6.5 0–8

TRAM flap [16, 43]. Noting a particularly dominant superficial inferior epigastric vein about 1.5 mm in diameter, which is evidence of its significant par− ticipation in venous drainage from abdominal tis− sues [16, 43], it is suggested to use it as an addi− tional venous outflow from the flap [45].

Paraumbilical

Perforator Flap

In 1998. Koshima et al. introduced a free tis− sue flap based on the paraumbilical perforator (PUP) [46]. The flap position generally corre− sponds to the location of the DIEP flap and its maximum size depends on the quality of the per−

forators and amounts to 45 ×22 cm (Fig. 3). As the

flap’s pedicle is the perforator cut at the level of the anterior rectus sheath, its pedicle is short and vessel diameters are approximately 0.7 mm [47, 48]. Some authors [47] suggested including the intra− muscular part of perforator, which allows pedicle extension to approximately 7 cm and an increase in vessel caliber. Despite the good aesthetic results, this flap has not been widely implemented due to technical difficulties [47].

Superior and Inferior Gluteal

Flaps

In 1976 the application of a flap based on the superior gluteal vessels was described for the first time in breast reconstruction [49]. The skin island of the superior gluteal flap may be obliquely ori− ented on the axis running from the posterior and

anterior iliac spine to the greater trochanter, or hor− izontally oriented extending laterally to the end of the gluteus maximus muscle and comprising a fragment of the adipose tissue covering the ten− sor fascia latae [50] (Fig. 4). A size of the skin island of approximately 13 x 25–30 cm enables primary wound closure at the donor site [11]. The blood supply comes from the superior gluteal ves− sels. The artery, the final branch of the interior iliac artery, divides above the piriform muscle into two branches: deep and superficial. Such a vessel course and the short pedicle (3–5 cm) [51] are the major technical inconveniences hampering anasto− mosis and frequently requiring a venous graft, especially at the junction with the thoracodorsal vessels [52]. Hence the most often proposed recip− ient vessels are the internal mammary vessels [53]. A flap modification is the superior gluteal artery perforator flap. Its advantage is a longer vascular pedicle and less morbidity at the donor site due to sparing of the gluteal muscle [54, 55].

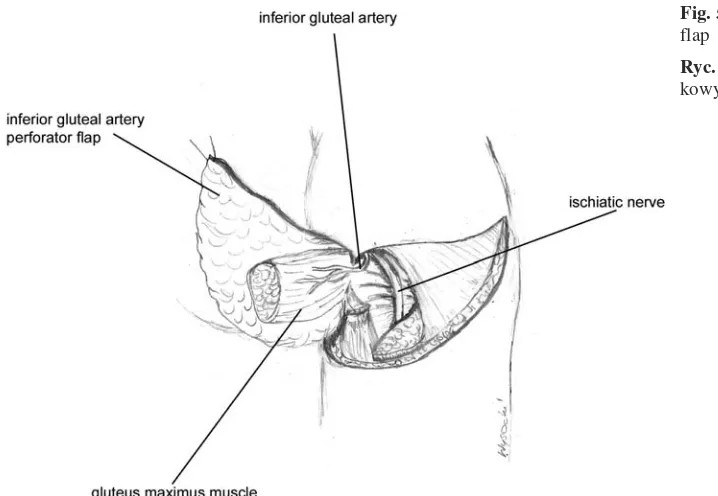

The inferior gluteal flap, mentioned for the first time by Le Quang [56], is supplied by the inferior gluteal artery, which is the final branch coming from the interior iliac artery (Fig. 5). The skin island is centrally positioned, just above the gluteal fold [56]. Its advantages are easier prepara− tion and longer vascular pedicle; moreover, the scar is hidden in the gluteal fold [57]. During flap preparation, a short (3–4 cm) length of the ischiat− ic nerve is exposed which requires careful protec− tion with local tissue to prevent sciatic neural− gia [57]. Moreover, postoperative neuroma of the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh may induce chronic pain [11].

Fig. 2.Deep inferior epigastric perforator flap (DIEP flap)

Rubens Flap

A free osteocutaneous flap based on the deep circumflex iliac artery (deep circumflex iliac artery flap, DCIA) and containing a fragment of iliac bone crest was described by Taylor et al. [58]. A modification with no bone, as a free cutaneous flap, was suggested and described by Hartrampf et al. in 1994 [59] and was defined as the Rubens flap. The great amount of adipose tissue in the iliac region allows using this flap as an alternative method in breast reconstruction. The blood supply is provided by musculocutaneous perforators com− ing from the descending branch of the deep cir−

cumflex iliac artery [60]. The pedicle is relatively long (5–6 cm) and the vessels’ diameters are suit− able for anastomosis with the axillary fossa or internal mammary vessels [95]. The long axis of the skin island runs parallel to the iliac bone crest. To increase the volume, 1/3 of the flap must be positioned beneath the iliac crest, which helps to harvest fat tissue from the upper areas covering the tensor fascia lata muscle and gluteal muscles. To protect the vascular pedicle, one ought to prepare together with the flap a fragment of oblique, inter− nal, and horizontal fascia as well as periosteum alongside the interior surface of the iliac crest [60]. It is widely held that the operation itself is more

Fig. 3. Paraumbilical perforator flap (PUP flap)

Ryc. 3. Płat na perforatorze okołopępkowym

(płat PUP)

Fig. 4.Superior gluteal artery perforator flap

difficult than harvesting a free TRAM flap; on the other hand, the operation is perceived as easier than harvesting a free superior gluteal artery per− forator flap [52]. During flap preparation, the lat− eral cutaneous femoral nerve and sensory branch of the Th12 nerve are spared, because their dam− age might contribute to paresthesia and numbness of the areas they innervate [11].

Lateral Transverse Thigh Flap

and Anterolateral Thigh Flap

The lateral transverse thigh flap is a horizontal variant of the myocutaneous flap from the tensor fascia lata muscle. The skin island might be ori− ented horizontally at the height of the so−called “saddle bags”, i.e. the fat tissue of the greater trochanter area, or obliquely, which facilitates aug− mentation of its dimensions [11]. The anterolater− al thigh flap is a universal flap that is gaining a reputation in soft tissue reconstructions, espe− cially in the head and neck area (Fig. 6).

The advantage of thigh flaps is the long and easy−to−prepare pedicle of lateral circumflex ves− sels peripherally entering the flap [51, 61, 62], with an average diameter of about 11 cm [51] and ves− sel diameters which correspond to the size of axil− lary vessels. It is worth emphasizing that especial− ly in the case of the anterolateral thigh flap, the average weight, amounting to 410 g, may prove to be insufficient for larger breast reconstruction [51]. The procedure might be performed simultaneously by two teams without changing the patient’s posi−

tion, but damage to the donor site, i.e. deformation of the thigh’s contour, is considerably great and the scar is difficult to conceal. A major complication at the donor site is a frequent accumulation of transu− date fluid that requires prolonged drainage [11].

Reconstruction

with Innervated Tissues

The objective is to reconstruct a symmetric and shapely breast with a consistency approximating that of the healthy breast. Much attention is devot− ed to regain sensitivity in the reconstructed breast. The patient has the opportunity to sense the recon− structed breast as an integral part of her body. Generally, sensitivity without sensory neurorraphy begins to return to the reconstructed breast in the period of one year following the procedure, but only some women report that the level of sensation has reached that of the healthy breast [63, 64]. Twenty− seven months after the operation, 56% of women with breast reconstruction with the latissimus dorsi muscle evaluate the sensitivity as very good or good, but as many as 70% of women find it poorer than in the normal side [10, 65]. The lateral cuta− neous branch of the dorsal primary divisions of the seventh thoracic nerve, which controls the sensation of the myocutaneous flap anastomosed to the later− al cutaneous branch of the fourth intercostal nerve controlling breast sensation, enables the recovery of flap sensation to the level of the healthy breast after one year [63, 64]. What is more, there are greater chances of restoring erogenous sensitivity [66], which returns only to a slight degree in reconstruc− tions without neurorrhaphy [65].

Fig. 5. Free interior gluteal flap

The development of techniques applying autologous tissue facilitates the reconstruction of a more natural breast with a permanent aesthetic result. Scars, contour changes, and deformations at the donor site occasionally require corrective pro− cedures modifying the symmetry. Knowledge of the advantages and disadvantages of the various flaps (Table 3) as well as clinical experience guar−

antee an individual approach and selection of the best reconstructive method. Applying microsurgi− cal techniques opened the way to the development of various methods allowing the performance of even the most extensive reconstructions with good aesthetic results, contributing to successful reha− bilitation and a return to normal psychosocial functioning.

Fig. 6.Anterolateral thigh flap

Ryc. 6. Perforatorowy płat przednio−boczny uda

Table 3. Comparison of flaps for autologous breast reconstruction

Tabela 3. Porównanie płatów stosowanych w rekonstrukcji piersi tkankami własnymi

Skin Bulk Contour Donor site Reliability Technical

(Jakość (Ilość (Projekcja appearance (Pewność ease skóry płata) tkanek) płata) (Wygląd miej− unaczynienia) (Łatwość

sca dawczego zabiegu)

po pobraniu płata) Free TRAM flap

(Wolny płat TRAM) ++++ +++ +++ +++ +++ +++

Pedicled TRAM flap

(Uszypułowany płat TRAM) +++ ++ ++ +++ ++ +++

Latissimus dorsi flap (Płat z mięśnia najszerszego

grzbietu) + + + ++ ++++ ++++

Gluteus flap

(Płat pośladkowy) +++ ++++ ++++ +++ ++ ++

Rubens flap

(Płat Rubensa) +++ +++ +++ ++ +++ ++

Lateral transverse high flap

(Boczny poprzeczny płat z uda) ++ ++ ++ + +++ ++

References

[1] Mathes SJ, Lang J: Breast Cancer: Diagnosis, Therapy, and Postmastectomy Reconstruction. In: Plastic Surgery. Mathes SJ (ed.), Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia 2006, 2nded., Vol. 6, pp. 631–789.

[2] Kroll SS:Breast reconstruction with autologous tissue. In: The unfavorable results in plastic surgery. Avoidance and treatment. Goldwyn RM, Cohen MN, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, London, Buenos Aires, Hong Kong, Sydney, Tokyo 2001, 3rded., 633–648.

[3] Lipa JE, Youssef AA, Kuerer HM, Robb GL, Chang DW: Breast reconstruction in older women: advantages of autogenous tissue. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003, 111, 1110–1121.

[4] Clough KB, O’Donoghue JM, Fitoussi AD, Nos C, Falcou MC:Prospective evaluation of late cosmetic results following breast reconstruction: I. implant reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001, 107, 1702–1709.

[5] Hartrampf CR Jr, Bennet GK:Autogenous tissue reconstruction in the mastectomy patient: A critical review of 300 patients. Ann Plast Surg 1987, 205, 508–518.

[6] Kroll SS, Baldwin B:A comparison of outcomes using three different methods of breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1992, 90, 455–462.

[7] Grotting JC, Urist MM, Maddox WA, Vasconez LO: Conventional TRAM flap versus free microsurgical TRAM flap for immediate breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1989, 83, 828–841.

[8] Grotting JC: immediate breast reconstruction using Free TRAM flap. Clin Plast Surg 1994, 21, 207–221.

[9] Clough KB, O’Donoghue JM, Fitoussi AD, Valstos G, Falcou MC:Prospective evaluation of late cosmetic results following breast reconstruction: II. TRAM flap reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001, 107, 1710–1716.

[10] Alderman AK, Wilkins EG, Lowery JC, Kim M, Davis JA: Determinants of Patient satisfaction in postmas− tectomy breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000, 106, 769–776.

[11] Shaw WW, Watson J, Ahn CY: Alternatives in autologous free−flap breast reconstruction. In: Georgiade Plastic, Maxillofacial and Reconstructive Surgery. Georgiadae GS, Riefkohl R, Levin LS, 3rded., Williams & Wilkins,

Baltimore, Philadelphia, London, Paris, Bangkok, Hong Kong, Munich, Sydney, Tokyo, Wrocław 1997, pp. 807–816.

[12] Hölmstrom H:The free abdominoplasty flap and its use in breast reconstruction. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg 1979, 13: 423–427.

[13] Moran SL, Nava G, Behnam AB, Serletti JM, Behnam AH:An outcome analysis comparing the thoracodor− sal and internal mammary vessels as recipient sites for microvascular breast reconstruction: a prospective study of 100 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003, 111, 1876–1882.

[14] Lantieri LA, Mitrofanoff M, Rimareix F, Gaston E, Raulo Y, Baruch JP: Use of circumflex scapular vessels as a recipient pedicle for autologous breast reconstruction: a report of 40 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg 1999, 104, 2049–2053.

[15] Arnez ZM, Bajec J, Bardsley AF, Scamp T, Webster MHC: Experience with 50 free TRAM flap breast recon− struction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1991, 87, 470−478.

[16] Nahabedian MY, Momen B, Galdino G, Manson PN:Breast reconstruction with the free TRAM or DIEP flap: patient selection, choice of flap, and outcome. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002, 110, 466–475.

[17] Chang DW, Wang B, Robb GL, Reece GP, Miller MJ, Evans GRD, Langstein HN, Kroll SS: Effect of obe− sity on flap and donor−site complication in free transversus rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap breast recon− struction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000, 105, 1640–1648.

[18] Padubidri AN, Yetman R, Browne E, Lucas A, Papay F, Larive B, Zins J: Complications of postmastectomy breast reconstruction in smokers, ex−smokers, and nonsmokers. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001, 107, 342–349.

[19] Chang DW, Reece GP, Wang B, Robb GL, Miller MJ, Evans GRD, Langstein HN, Kroll SS:Effect of smok− ing on complications in patients undergoing free TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000, 105, 2374–2380.

[20] Sozer SO, Cronin ED, Biggs TM, Gallegos ML: The use of the transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap after abdominoplasty. Ann Plast Surg 1995, 35, 409–411.

[21] Ribuffo D, Marcellino M, Barnett GR, Houseman ND, Scuderi N:Breast reconstruction with abdominal flaps after abdominoplasties. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001, 108, 1604–1608.

[22] Tran NV, Chang DW, Gupta A, Kroll SS, Robb GL: Comparison of immediate and delayed free TRAM flap breast reconstruction in patients receiving postmastectomy radiation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001, 108, 78–82.

[23] Schusterman MA, Kroll SS, Weldon ME: Immediate breast reconstruction: why the free TRAM over the con− ventional TRAM flap? Plast Reconst Surg 1992, 90, 255–261.

[24] Kroll SS: Fat necrosis in free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous and deep inferior epigastric perforator flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000, 106, 576–583.

[25] Kroll SS:Bilateral breast reconstruction in very thin patients with extended free TRAM flaps. Br J Plast Surg 1998, 51, 535–537.

[26] Baldwin BJ, Schusterman MA, Miller MJ, Kroll SS, Wang BG: Bilateral breast reconstruction: conventional versus free TRAM. Plast Reconstr Surg 1994, 93, 1410−1416.

[27] Moran SL, Serletti JM: Outcome comparison between free and pedicled TRAM flap breast reconstruction in obese patient. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001, 108, 1954–1960.

[29] Scheufler O, Andersin R, Kirch A, Banzer D, Vaubel E: Clinical results of TRAM flap delay by selective embolization of the deep inferior epigastric arteries. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000, 105, 1320−1329.

[30] Banic A, Boeckx W, Guelickx GP, Marchi A, Rigotti G, Tschopp H:Late results of breast reconstruction with free TRAM flap: a prospective multicentric study. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995, 95, 1195–1204.

[31] Blondeel PN, Arnstein M, Verstraete K, Depuydt K, Van Landuyt KH, Monstrey SJ, Kroll SS:Venous con− gestion and blood flow in free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous and deep inferior epigastric perforator flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000, 106, 1295–1299.

[32] Watterson PA, Bostwick J 3rd, Hester TR Jr et al.: TRAM flap anatomy correlated with a 10−year clinical expe− rience with 556 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995, 95, 1185–1194.

[33] Pennington DG, Nettle WJS, Lam P: Microvascular augmentation of the blood supply of the contralateral side of the free transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap. Ann Plast Surg 1993, 31, 123–127.

[34] Elliott LF, Eskenazi L, Beegle PH Jr, Podres PE, Drazan L: Immediate TRAM flap breast reconstruction: 128 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg 1993, 92, 217–227.

[35] Schusterman MA, Kroll SS, Miller MJ, Reece GP, Baldwin BJ, Robb GL, Altmyer ChS, Ames FC, Singletary SE, Ross MI, Balch ChM:The free transversus rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap for breast reconstruction: one center’s experience with 211 consecutive cases. Ann Plast Surg 1994, 32, 234–241.

[36] Nahabedian MY, Manson PN: Contour abnormalities of the abdomen after transverse rectus abdominis muscle flap breast reconstruction: a multifactorial analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002, 109, 81–87.

[37] Nahaedian MY, Dooley W, Singh N, Manson PN: Contour abnormalities of the abdomen after breast recon− struction with abdominal flaps: the role of muscle preservation. Plast Reconst Surg 2002, 109, 91–101.

[38] Mizgala CL, Hartrampf CR Jr, Bennett GK: Assessment of the abdominal wall after pedicled TRAM flap surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 1994, 93, 988–1002.

[39] Kroll SS, Schusterman MA, Reece GP, Miller MJ, Robb G, Evans G: Abdominal wall strength, bulging, and hernia after TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconst Surg 1995, 96, 616–619.

[40] Suominen S, Asko−Seljavaara S, von Smitten K, Ahovouo J, Sainio P, Alaranta H: Sequelae in the abdomi− nal wall after pedicled or free TRAM flap surgery. Ann Plast Surg 1996, 36, 629–636.

[41] Blondeel N, Vanderstraeten GG, Monstrey SJ, Van Landuyt K, Tonnard P, Lysens R, Boeckx WD, Matton G:

The donor site morbidity of free DIEP flaps and free TRAM flaps for breast reconstruction. Br J Plast Surg 1997, 50, 322–330.

[42] Arnaz ZM, Kahn U, Pogorelec D, Planinsek F:Rational selection of flaps from the abdomen in breast recon− struction to reduce donor site morbidity. Br J Plast Surg 1999, 52, 351–354.

[43] Kroll SS: Fat necrosis in free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous and deep inferior epigastric perforator flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000, 106, 576–583.

[44] Blondeel PN: One hundred free DIEP flap breast reconstruction: a personal experience. Br J Plast Surg 1999, 52, 104–111.

[45] Wechselberger G, Schoeller T, Bauer T, Ninkovic M, Otto A, Ninkovic M: Venous superdrainage in deep infe− rior epigastric perforator flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001, 108, 162–166.

[46] Koshima I, Inagawa K, Urushibara K, Moriguchi T:Paraumbilical perforator flap without deep inferior epi− gastric vessels. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998, 102, 1052–1057.

[47] Schoeller T, Bauer T, Gurunluoglu R, Hussel H, Otto−Schoeller A, Piza−Katzer H, Weschselberger G:

Modified free paraumbilical perforator flap: the next logical step in breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003, 111, 1093–1098.

[48] Koshima I, Inagawa K, Yamamoto M, Moriguchi T: New microsurgical breast reconstruction using free paraumbilical perforator adiposal flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000, 106, 61–65.

[49] Fujino T, Harashina T, Enomoto K:Primary breast reconstruction after a standard radical mastectomy by a free flap transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg 1976, 58, 371–374.

[50] Shaw WW:Mircovascular free flap breast reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg 1984, 11, 333–343.

[51] Wei FC, Suominen S, Cheng MH, Celik N, Lai YL:Anterolateral thigh flap for postmastectomy breast recon− struction. Plast Recostr Surg 2002, 110, 82–88.

[52] Evans GRD, Kroll SS: Choice of technique for reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg 1998, 25, 311–316.

[53] Shaw WW: Breast reconstruction by superior gluteal microvascular free flaps without silicone implants. Plast Reconstr Surg 1983, 72, 490−499.

[54] Allen RJ, Tucker C Jr: Superior gluteal artery perforator free flap for breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995, 95, 1207–1212.

[55] Blondeel PN:The sensate free superior gluteal artery perforator (S−GAP) flap: a valuable alternative in autolo− gous breast reconstruction. Br J Plast Surg 1999, 52, 185–193.

[56] Le−Quang C:Two new free flaps developed from aesthetic surgery. II. The inferior gluteal flap. Aesthet Plast Surg 1980, 4, 1597–1608.

[57] Paletta CE, Bostwick J 3rd, Nahai F:The inferior gluteal free flap in breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1989, 84, 875–883.

[58] Taylor GI, Watson N:One−stage repair of compound leg defects with free, revascularized flaps of groin skin and iliac bone. Plast Reconstr Surg 1978, 61, 494–506.

[60] Taylor GI, Townsend P, Corlett R: Superiority for the deep circumflex iliac vessels as the supply for free groin flaps: experimental work. Plast Reconstr Surg 1979, 64, 595–604.

[61] Beckenstein MS, Grotting JC:Breast reconstruction with free−tissue transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001, 108, 1345–1353.

[62] Elliott LF, Beegle PH, Hartrampf CR Jr:The lateral transverse thigh free flap: an alternative fog autogenous− tissue breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1990, 85, 169–178.

[63] Yano K, Matsuo Y, Hosokawa K:Breast reconstruction by means of innervated rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998, 102, 1452–1460.

[64] Yano K, Hosokawa K, Takagi S, Nakai K, Kubo T:Breast reconstruction using the sensate latissimus dorsi mus− culocutaneous flap. Plast Reconst Surg 2002, 109, 1897–1902.

[65] Delay E, Jorquera F, Lucas R, Lopez R:Sensitivity of breast reconstructed with the autologous latissimus dorsi flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000, 106, 302–309.

[66] Blondeel PN, Demuynck M, Mete D, Monstrey SJ, Van Landuyt K, Matton G, Vanderstraeten GG:Sensory nerve repair in perforator flaps for autologous breast reconstruction: sensational or senseless? Br J Plast Surg 1999, 52, 37–44.

Address for correspondence:

Piotr WójcickiJana Pawła II 2 57−320 Polanica Zdrój Poland

Tel.: +48 74 862 11 59

E−mail: p.wojcicki@chirurgiaplastyczna.biz.pl

Conflict of interest: None declared