Preventing violence:

© World Health Organization 2013

All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO web site (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: bookorders@who.int). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO web site (www.who.int/about/ licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html).

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement.

The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters.

All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use.

Designed by minimum graphics

Printed by Imprimerie Centrale, Luxembourg

WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data :

Preventing violence: evaluating outcomes of parenting programmes.

1.Violence – prevention and control. 2.Parenting. 3.Child abuse. 4.Program evaluation – methods. 5.Family relations. I.World Health Organization. II.UNICEF. III.University of Cape Town.

Contents

The context of this guidance

1

Section 1

What is ‘outcome evaluation’ and why do we need it?

3

What is ‘programme evaluation’ ?

3

Reasons people are reluctant to have their programmes evaluated –

and why evaluations are nonetheless important

5

How do outcome evaluations show whether a programme is effective?

6

Summary of section 1

9

Section 2

The evidence: what do we know?

10

Evidence of the effectiveness of parenting programmes

10

Adapting parenting programmes to other cultures

11

The main features of effective programmes

12

Summary of section 2

14

Section 3

Outcome evaluation: how do we do it?

15

Activities before an evaluation

15

The outcome evaluation process

16

Conclusion

20

References

21

This document is a product of the Parenting Project Group, a project group of the World Health Organiza-tion’s Violence Prevention Alliance. The text was written by Inge Wessels, with critical commentary provided by Christopher Mikton, Catherine L. Ward, Theresa Kilbane, the other members of the Parenting Project Group (Bernadette Madrid, Giovanna Campello, Howard Dubowitz, Judy Hutchings, Margaret Lynch and Re-nato Alves), Lisa Jones and additional reviewers who are involved with parenting programmes to prevent violence. This project and publication was kindly funded by the UBS Optimus Foundation.

The context of this guidance

Violence is both a serious human rights violation and a major public health concern. It affects the general well-being, physical and mental health, and social functioning of millions of people (1); it also puts strain on health systems, lowers econom-ic productivity, and has a negative effect on eco-nomic and social development (2). In particular, the number of children affected by violence each year is a major concern (3).

Child maltreatment affects children’s physical, cognitive, emotional and social development. It can lead to the body’s stress response system be-ing overactive, which can harm the development of the brain and other organs, and increase the risk for stress-related illness and impaired cogni-tion (the capacity to think, learn and understand) (4). Maltreatment is a risk factor for mental health, education, employment and relationship problems later in life. It also increases the likelihood of be-haviour that is a risk to health, such as smoking, drinking heavily, drug use, over-eating and unsafe sex (5). These behaviours are, in turn, major caus-es of death, disease and disability, including heart disease, cancer, diabetes and suicide – sometimes decades later (5). Victims of maltreatment are also more likely to become perpetrators and victims of other types of violence later in life (6).

Child maltreatment negatively affects a coun-try’s economy, due to expenses relating to treating victims’ health problems, welfare costs, lowered economic productivity and so forth (7). In the Unit-ed States of America (USA), in 2010, the lifetime cost for each victim of non-fatal child maltreatment was estimated to be US$ 210 012 (7). The many se-rious economic, physical and mental health conse-quences of child maltreatment mean that it makes sense to develop and implement effective preven-tion strategies.

Child maltreatment is more likely in families that have difficulties developing stable, warm and positive relationships (8). Children are at increased risk of being maltreated if a parent or guardian has a poor understanding of child development, and therefore has unrealistic expectations about the child’s behaviour (8). This is also the case if parents and guardians do not show the child much care or affection, are less responsive to the child, have a harsh or inconsistent parenting style, and believe that corporal punishment (for example, smacking) is an acceptable form of discipline (1, 5). Strength-ening parenting1 therefore plays an important role in preventing child maltreatment.

One way of strengthening parenting is through parenting programmes. Although many parenting programmes do not specifically aim to reduce or prevent violence, those which aim to strengthen positive relationships through play and praise, and provide effective, age-appropriate positive disci-pline, have the potential to do so (9).

Parenting programmes to prevent violence usual-ly take the shape of either individual or group-based parenting support. An example of individual par-enting support is home visits, which involve trained home visitors visiting parents (typically only the mother) in their homes both during and after their pregnancy. The home visitor supports and edu-cates parents so as to strengthen parenting skills, improve child health and prevent child maltreat-ment (10). Group-based parenting support, on the other hand, is typically provided by trained staff to groups of parents together. These programmes aim to prevent child maltreatment by improving parenting skills, increasing parents’ understanding

1 Throughout this document, parenting does not only refer

of child development and encouraging the use of positive discipline strategies (10).

Most parenting programmes that have proven to be effective at preventing violence have been developed and tested in high-income countries such as the USA and the United Kingdom. There is very little work on parenting programmes in low- and middle-income countries. However, there is evidence from low-resource settings that positive parent-child relationships and a positive parenting style can buffer the effects of family and commu-nity influences on children’s development, includ-ing violent behaviour later in life (11, 12). From what is already known, there is good evidence to support promoting parenting programmes across different cultural and economic backgrounds.

Because we do not know enough about par-enting programmes in low- and middle-income countries, evaluations of programmes are critical. First, we need to confirm that desired results are achieved in new contexts. Second, because of the lack of resources available to fund programmes in poorer countries, evaluations can prevent time and money from being wasted on programmes that do not work. Third, the results from outcome evalua-tions can be used to influence governments to fund parenting programmes.

This document was designed to help strength-en the evidstrength-ence for parstrength-enting programmes aimed

at preventing violence in low- and middle-income countries. The intended audiences are:

• policy-makers;

• programme developers, planners and com-missioners;

• high-level practitioners in government minis-tries, such as health and social development; • nongovernmental organisations;

• community-based organisations; and • donors working in the area of violence

pre-vention.

After going through this document, you should:

• understand the need for solid evidence of a programme’s effectiveness;

• know about the current literature on parent-ing programmes aimed at preventparent-ing vio-lence; and

• understand the process of carrying out out-come evaluations of parenting programmes aimed at preventing violence.

SECTION 1

What is ‘outcome evaluation’ and

why do we need it?

What is ‘programme evaluation’ ?

Put simply, programme evaluation is a process which involves collecting, analysing, interpreting and sharing information about the workings and effectiveness of programmes (13). Different types of evaluation are appropriate at different stages of a programme – from the design stage, through to long-term follow-up of participants after the pro-gramme has ended (13). The earlier a propro-gramme is evaluated, the stronger the programme is likely to be.

Needs assessment

A programme is created so that it can tackle a particular problem. Understanding the nature of the problem and how common and widespread it is can help to make sure that the programme be-ing developed meets the intended purpose, and whether there actually needs to be a programme. A needs assessment should be carried out when the programme is first thought of or when an existing programme is restructured, as it can identify what services are needed and how they should be pro-vided.

Below is an example of how a needs assess-ment might be used. The programme in the exam-ple – Caring Families – is fictional and will be used as an example throughout this document.

Developing and assessing the programme theory

Once the need for a programme has been estab-lished, the next step is to develop a programme theory and assess it. All programme staff should work together to create the programme theory be-fore the programme is developed. A programme theory is a blueprint that represents how the pro-gramme is supposed to work and acts as a guide to how the programme should be designed and delivered so that it achieves its desired effects. Creating a diagram can help produce the programme theory as it makes it easier to see the mechanisms through which the programme hopes to achieve its aims (see Annex on Creating a diagram of pro-gramme theory). By carrying out an assessment of this theory (that is, by checking whether current scientific evidence suggests that the individual ele-ments of the programme, as suggested in the the-ory, are likely to make the programme a success),

EXAMPLE

The developers of Caring Families aim to tackle the problem of child maltreatment. Before designing the programme, they interviewed clients using their support centre to understand how many of the parents they helped were at risk of maltreating their children, and whether this came about because the parents did not understand:

n what was appropriate for different developmental stages of children; or

n that corporal punishment is not an effective discipline technique.

you can gain an understanding of whether or not the programme is likely to achieve its goal. Feed-back from the assessment can be used to improve the programme.

Assessing the programme process

A feasible programme theory, based on evidence about what works, is not enough to make sure that the programme will be effective. The programme must also be delivered according to a set plan. The process of delivering the programme needs to be monitored to make sure it is in line with the planned process. The evaluation may investigate whether or not services are being delivered to the intended parents, how well the services are being delivered, and how resources for the programme are allocated. Process evaluation allows for neces-sary checks to be made before an outcome evalu-ation can be carried out. If the programme is not being delivered to the intended group, or not being delivered as planned, it will probably not meet its original goals and an outcome evaluation would be a waste of time.

Routinely monitoring the key elements of a pro-gramme – through careful record-keeping and reg-ular reporting – is an important part of evaluations. Information from the monitoring is essential to an outcome evaluation, and can also be used to adapt the programme as time goes on.

Outcome evaluation

Outcome evaluation (also known as impact assess-ment or impact evaluation) investigates the de-gree to which a programme produces the intended changes to the problem. In other words, did the pro-gramme achieve its desired outcomes?

Although all evaluation types are important, this document focuses specifically on outcome evalua-tion because it is the only type of evaluaevalua-tion that can determine whether or not a programme is effective. There are various outcome evaluation methods, with the randomised controlled trial the “gold standard” – it is the approach most able to isolate whether the programme did have an effect. A randomised con-trolled trial allows a comparison to be made between groups – which are equivalent – who either received or did not receive the programme. There are also EXAMPLE

Caring Families developed a programme theory, which clearly states the mechanisms through which the programme hopes to prevent child maltreatment. The programme implementers will teach parents what to expect of children at different stages of development, so that they do not place unrealistic demands on their children. They will also teach parents positive discipline techniques – such as reinforcing good behaviour through praise and ‘time outs’ – so parents do not resort to hitting their children. They will then check whether current scientific evidence suggests that these individual elements of the programme theory are supported by any evidence.

EXAMPLE

The Caring Families team produced a programme plan that identified how they thought the programme should be delivered to have the maximum effect. The plan suggested, amongst other things that:

n the programme should be delivered over 12 three-hour sessions to high-risk parents of children aged three to eight years old; and

n programme staff should receive ongoing support and supervision. Monitoring the programme might include:

n checking that parents attending the programme are actually ‘high-risk’, according to the definition they developed earlier, and have children in the defined age-group;

n keeping attendance registers to check whether parents are actually attending the programme; and

less rigorous methods, such as quasi-experiments, which – although less powerful – do produce useful information on programme effectiveness.

Reasons people are reluctant to have their programmes evaluated – and why evaluations are nonetheless important

When doing hands-on work with parents, programme staff may see that parents’ behaviour changes after taking part in the programme. So it may be difficult to understand the importance of carrying out an outcome evaluation, especially given the significant resources that it requires (14). People working with parenting programmes may be reluctant to carry out an outcome evaluation because they:

• already have a sense that the programme is working;

• do not have time to carry out an evaluation; • do not have the funds to carry out an

evalu-ation; or

• are worried about getting negative results. In this part of the guide we explain why some of these reasons may be preventing programmes from reaching their full potential.

Having a sense that the programme is working

Service providers may have a strong feeling that a programme is effective, based on positive feed-back from the parents involved (14). Unfortunately, countless programme evaluations have shown that such opinions are often incorrect (14). Positive re-actions to a programme may arise simply because parents like the people involved in the programme sessions, and this approval may not necessarily translate into changes in parents and their children (14). Donors also generally are attracted to hard evidence that a programme works, and so are more likely to fund those with outcome evaluations showing evidence of effectiveness.

Having no time to carry out the evaluation

A common reason for not performing an outcome evaluation is that it takes too much time (14). This may be especially true if staff are doing a lot of ur-gent work (which is typical of many child protection and family service agencies). As a result, the cost of slowing down for an outcome evaluation may seem unjustified (14). However, the cost of not per-forming an outcome evaluation may be even higher (14). Without one, it is impossible to tell whether a programme has very little impact, or even harmful effects. This may not only lead to a waste of

re-sources, it can also prevent parents from receiving programmes that can make a positive difference in their lives. Seldom do evaluations find absolutely no effect, but there are some cautionary tales from the public health literature: Healthy Families Amer-ica, the original D.A.R.E. (Drug Abuse Resistance Education) programme and the ‘Scared Straight’ programme.

• Healthy Families America (http://www.healthy-familiesamerica.org/home/index.shtml) is the most well-known programme of the Prevent Child Abuse America initiative. It is a home-visiting programme which serves families who are at risk of adverse childhood experiences, including child maltreatment. Despite being widely imple-mented in the USA for many years, there is no solid evidence that the programme is effective at preventing child maltreatment (15, 16, 17). • For over 20 years, the original D.A.R.E.

pro-gramme (http://www.dare.com/home/default. asp) was the most popular school-based drug abuse prevention programme in the USA. Dur-ing this time, hundreds of millions of US$ were used to run the programme (18). Evaluations found that students’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour improved immediately after the pro-gramme, but faded away over time. By their late teens, there was no difference between students who took part in the programme and those who didn’t (18). This is a very big problem, especial-ly when considering the large sums of money invested. In response to continuous negative feedback, D.A.R.E. adopted the keepin’ it REAL curriculum in 2009. This curriculum has led to a range of positive outcomes for youth, including reductions in alcohol use (19).

There is no doubt that an outcome evaluation takes a great deal of staff time. However, if a pro-gramme sets up efficient monitoring and evaluation procedures from the start, the process of preparing for and performing an outcome evaluation will take less time. Hiring an external evaluator is recom-mended because the evaluation is likely to be more objective and so more credible to outsiders, such as sponsors and donors (14); it also means that far less staff time will be spent on the evaluation.

Not having funds to carry out the evaluation

Funding shortages are often a major barrier to carrying out outcome evaluations. For many pro-grammes, performing outcome evaluations can seem like an unnecessary cost, especially if it seems that the money would be better spent pro-viding services. However, not carrying out evalu-ations can actually waste a lot of money – money that could have been better spent elsewhere, on better services. In order to do as much good as possible with available resources, programmes need to be evaluated early to check whether they are effective. By identifying effective programmes, and introducing them on a wide scale when funding is available, many more families can benefit from them. This is an important lesson for donors as well as programme staff, and funding to carry out evalu-ations should be included in budgets when apply-ing for any grant or government support.

Being worried about getting negative results

Programme developers and managers often fear that if an outcome evaluation of their programme shows little benefit, it may reflect badly on the or-ganisation and be harmful to the programme (14, 22). Although an outcome evaluation may indeed reveal that some aspects of the programme are not working as planned, it is extremely rare for pro-grammes to be closed down because of the findings of an evaluation. Outcome evaluations provide an opportunity to refine and improve the programme that would not be possible if an evaluation were not carried out. Evaluation might also highlight aspects of the programme that are working better than expected, which may boost the morale of pro-gramme staff.

There are benefits to the organisation running the programme, but there are also benefits to the greater good. Making the results of an outcome evaluation public, whether those results are posi-tive or negaposi-tive, helps to build up a solid base of evidence (23). This means others can gain a better

understanding of what does and does not work in parent programmes, and may lead to existing pro-grammes being improved and new high-quality ones being developed. For instance, from the es-tablished evidence base we know that parent guid-ance programmes that simply talk to parents are not as effective as those which give parents the opportunity to actively apply what they are learn-ing through, for example, role-play and practice at home (9, 24). This helps us know how to approach the task of designing new parenting programmes.

Evidence from outcome evaluations is also an important tool for advocacy purposes and to con-vince policy makers to invest in initiatives to prevent violence. In the past, getting support and funding for violence prevention activities has been a chal-lenge. However, with strong evidence of effective-ness, government leaders can be convinced of the benefits of widespread parenting programmes.

How do outcome evaluations show whether a programme is effective?

The goal of outcome evaluation is to estimate whether the programme caused changes in parent-ing – both whether there were changes, and whether it was the programme and not something else that caused them – and how big those changes were. To do this, the evaluation must assess the parents on the programme’s key expected outcomes (for exam-ple, how confident they are in their parenting, and the level of child behaviour problems experienced), and estimate what the status would have been at that time if the parent had not taken part in the pro-gramme. The latter is known as the counterfactual and describes an impossible state of affairs – the parent cannot have taken part in the programme and have not taken part (25). Nonetheless, the causal effect of the programme is defined as the difference between what did happen at the end of the programme (factual) and what would have hap-pened during the same period, to the same people, without the programme (counterfactual).

people in the intervention group. The best way to do this is to place people in the groups at random (known as random assignment). If a large enough number of participants is randomly assigned to the groups, the differences in characteristics between the groups are likely to be cancelled out and the groups should be equivalent on all characteristics – measured and unmeasured. If the intervention and comparison groups are not identical on all charac-teristics, differences between the two groups when the programme is over could be due to the differ-ences in pre-existing characteristics rather than the effects of the programme.

The strength of the conclusions that can be drawn from an evaluation depends on the type of outcome evaluation carried out. The different types of outcome evaluation can be ordered according to the strength of the evidence they produce to esti-mate the causal effect. These types, in order from strongest to weakest, are:

• randomised controlled trials (true experi-mental designs);

• quasi-experimental designs; • single group designs; and • non-experimental designs.

These are briefly explained on the next few pages. Programme evaluators should choose the type of evaluation that allows for the strongest possi-ble conclusions about causal effects. There are a number of factors that need to be considered when choosing the appropriate evaluation method, in-cluding how long the programme has been in place, the availability of financial and human resources, and the questions that need to be answered about the programme (26).

Randomised controlled trials

Randomised controlled trials, or true experiments, are often considered to be the ‘gold standard’ for outcome evaluation because they are best at esti-mating if the programme caused a difference and

how big this difference was. In randomised con-trolled trials, parents in the target population are randomly assigned to either the intervention group or the comparison group. This results in an inter-vention group that is equivalent to the comparison group before the programme starts. As only one group takes part in the programme, the evalua-tor can be reasonably sure that any difference be-tween the groups after the programme is due to the effects of the programme and nothing else.

Through using random assignment and having a comparison group, randomised controlled trials typically have the highest ‘internal validity’ of all the types of evaluation. Internal validity refers to how much confidence people can have that it is the programme and not some other extraneous factor that caused the change. Threats to internal valid-ity include history and maturation. History refers to any outside event that happened at the same time as the programme and which may have led to changes in the people taking part in the pro-gramme. Maturation, on the other hand, refers to how people naturally change over time, rather than as a result of the programme.

While the randomised controlled trial is the best type of evaluation to determine a programme’s ef-fectiveness, it uses the most resources. As a result, it may not be viable for some programmes, espe-cially those which are in low- and middle-income countries and have very limited resources. Never-theless, programmes should carry out randomised controlled trials where possible. They are particu-larly important for programmes that aspire to be considered evidence-based and intend to scale up for widespread roll-out; only the randomised con-trolled trial can provide sufficient evidence that a programme is sound enough for scaling up. Ran-domised controlled trials are most suitable for pro-grammes that have already shown to be promising through pilot studies (14).

Although the randomised controlled trial is the strongest type of evaluation, there are possible

EXAMPLE

ethical dilemmas. Even if a programme has not yet gathered enough evidence to show that it is effec-tive, if the programme is carefully designed there is undoubtedly the chance that it may be effective. Using a comparison group that does not get the programme can therefore deprive people of pos-sible benefit. However, this can be overcome by a “wait-list” control group; that is, the comparison group does get the programme, although only after the trial is over. In a well-designed trial, that might be a year or more after the first group got the pro-gramme.

Quasi-experimental designs

Quasi-experimental evaluations have most of the same elements as randomised controlled trials. The main difference is that quasi-experiments do not in-volve randomly placing people in the intervention or comparison group. Because of this, the intervention group and comparison group are considered not to be equivalent at the start of the experiment.

If this type of evaluation is used, the evalua-tor needs to choose a comparison group that is as similar as possible to the intervention group. The relevant characteristics of the people in the com-parison group need to match those of the people in the intervention group. This matching is done by pairing individuals who have identical characteris-tics considered to be relevant and important for the particular evaluation. Through this process, the two groups will probably have equivalent characteris-tics (27). A problem with matching is that if some of the important characteristics are overlooked in the matching process, the resulting groups may not actually be equivalent, and the evaluation results may be compromised (27).

An alternative to matching individuals is to use statistical controls, or make statistical adjustments for the differences between the groups that might otherwise lead to biased estimates of the effects of the programme (13). This means one has to be

sure to measure the things that might be important – which again is risky, as one might miss some im-portant measures. As with matching people in the groups, one cannot be sure that statistical control during the analysis of data after the programme has been delivered would completely remove the bias due to non-random assignment to intervention and control groups (25). There is no way to know to what extent the differences, which are not controlled for, may produce misleading evaluation results (25).

Single group designs

Of the quasi-experimental methods of evaluation, single group designs are the least able to provide evidence of a causal effect. This is because they focus on a single group of parents who took part in the programme without making a comparison with an equivalent group that did not take part in the programme. An example of a single group design is the ‘pre- and post-test’ method. In this design, measures are simply taken from parents before and after they take part in the programme. By looking at the information gathered before and after the programme, the evaluator can gain an idea of the programme’s effect. While the information gath-ered may be useful for routine monitoring, it does not produce credible estimates of the change that is due to the programme alone. The estimates may be biased because they include the effects of other influences on the parents between the pre-test and post-test measurements (13).

Non-experimental designs

If, for some reason, it is not possible to use an ex-perimental method of evaluation, a programme may benefit from a non-experimental alternative, such as a theory-based evaluation, or a series of single case studies. However, these methods are less robust in determining whether or not a pro-gramme is effective at achieving its aims.

There are two main types of non-experimental

EXAMPLE

evaluations – theory-based evaluations and quali-tative case study evaluations.

A theory-based evaluation focuses on the assumptions the programme is based on, as well as focusing on results, as experimental designs do (28). This type of evaluation examines the connections between the programme’s context, mechanisms of change, and outcomes – ultimately ‘testing’ the programme theory the programme staff produced. The ability to test a programme theory depends on three factors (28):

• how well the theory is defined (it should be well-defined and agreed upon by various stakeholders);

• how well programme activities reflect the assumptions the theory is based on (there needs to be a clear match between theory and practice); and

• the resources available for the evaluation (a thorough evaluation will require a substan-tial amount of resources, in terms of both time and money).

Those who support theory-based evaluation see it as an attractive alternative to experiments (25). This is because it only involves an intervention group and not a comparison group, so may need fewer resources (25). Also, showing that there is a match between theoretical predictions and the informa-tion gathered suggests a causal effect without hav-ing to consider alternative explanations, which can typically take a long time (25). Lastly, it is often dif-ficult to measure long-term outcomes (for example, reductions in youth violence may only be evident fifteen years after a programme for parents of young children is over), so confirmation of short-term out-comes (for example, reductions in harsh parenting) through theory-based evaluations can suggest that the programme is on the right track (25).

A qualitative case study is an ‘intensive, holistic description and analysis of a single entity, phenom-enon, or social unit’ (29). For example, a case study may focus on the experiences of a particular group

of parents as they go through the Caring Families programme. This method of evaluation can help to identify possible causal effects, provide an under-standing of the factors that may condition these effects, and answer a broader range of questions about the programme and how participants experi-ence it, than would be possible with experimental designs (25).

Although case-study methods can reduce some uncertainty about the causal effects of a pro-gramme, solid conclusions cannot be drawn (25). The factors that shape the experience of a small group of parents in a parenting programme may not apply to larger samples of parents. Because there is no comparison group, it is difficult to determine whether changes are due to the programme or to other factors.

Summary of section 1

• Outcome evaluation can tell us how well a pro-gramme works (that is, whether the propro-gramme does in fact cause changes in parents’ or chil-dren’s behaviour, and how big those changes are). • The results of outcome evaluation allow

parent-ing programmes to be improved, and add to the evidence others can then draw from when choos-ing programmes or developchoos-ing programmes of their own.

• Knowing whether or not a programme is effective ensures that parents are receiving programmes that actually work, and enables resources to be spent wisely.

• A randomised controlled trial allows for the strongest conclusions to be drawn about the effectiveness of a programme. However, due to economic, logistical, or ethical reasons, this method of evaluation may not always be feasi-ble. Although another method may be more ap-propriate for the evaluation, it is important to remember that it will not provide the same de-gree of confidence in the findings.

EXAMPLE

SECTION 2

The evidence: what do we know?

has shown positive results in three randomised controlled trials across various samples and re-gions in the USA (16). Results from one of these trials showed that during the second year of the child’s life, children of parents in the intervention group had 32% fewer visits to the emergency de-partment than those in the comparison group (35). Of those visits, there were 56% fewer for injuries and swallowing dangerous substances (35). By the 15-year follow-up, rates of child abuse were reduced by 48% compared with the children in the control group (36).

The evidence for the Nurse Family Partnership is promising. Several randomised controlled trials all point in the same very positive direction, suggest-ing that home-visitsuggest-ing can improve parentsuggest-ing and child safety. However, a major drawback of home-visiting programmes is that they can be expensive and may not be affordable for low- and middle-income countries. For example, the estimated to-tal cost of the Nurse Family Partnership is around US$ 4 500 a year for each person taking part in the programme (37). If a home-visiting programme is modified in any way to reduce cost (for example, by using community workers instead of highly-trained nurses), it may not be as effective, and so should be evaluated to check whether there is an effect.

Parent guidance programmes have also been shown to be effective in preventing child maltreat-ment (8). The success of the Triple P – Positive Parenting Program (www.triplep.net) in reducing rates of child maltreatment has been shown in a randomised controlled trial, which involved deliv-ering Triple P professional training to the existing workforce, together with media coverage and com-munication strategies, across 18 randomly chosen counties in one state of the USA (32). The results showed that Triple P has preventative effects on This section is made up of three parts. The first

re-views evidence on the effectiveness of parenting programmes aimed at preventing violence. The sec-ond discusses the issues around adapting parent-ing programmes for cultures other than those they were originally developed for. The last part sets out the characteristics that are common to effective programmes.

Evidence of the effectiveness of parenting programmes

Evidence suggests that improving relationships between parents and their children, and teach-ing parentteach-ing skills, can be effective in preventteach-ing violence. Over the next few pages we will review evidence on preventing child maltreatment, behav-ioural problems in children and youth violence.

Preventing child maltreatment

Many parenting programmes have been developed to prevent child maltreatment, but few have been evaluated (16). Of the programmes that have been evaluated, evidence suggests that some may be effective at preventing child maltreatment (30, 31, 32) as well as improving aspects of family life that are likely to be associated with maltreatment (8), such as parental attitudes and parenting skills (33, 34).

three population indicators of child maltreatment, namely substantiated cases of child maltreatment, child out-of-home placements, and child injuries from maltreatment. Although these findings are promising, more trials are needed (16). One ran-domised controlled trial alone does not provide strong enough evidence of effectiveness – there is always the possibility that these changes were found by chance. What is needed for greater cer-tainty is several studies that all point in the same direction.

Preventing behavioural problems

Children with behavioural problems from an early age are at a higher risk of a range of negative out-comes, including violent behaviour later in life (9). It is encouraging that some parent guidance pro-grammes have been shown to be effective at pre-venting these types of behavioural problems in children. For instance, a randomised controlled trial of the Incredible Years Parent Programme (http:// www.incredibleyears.com) in Wales showed that the programme led to significant improvement in child behaviour, as well as in parents’ mental health and positive parenting (38). The benefits also spread to the sibling nearest in age (38). The findings from other randomised controlled trials, including those conducted in Canada, Jamaica, and Norway also reflect the effectiveness of the Incred-ible Years in achieving positive outcomes.

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (http://pcit. phhp.ufl.edu/) is another parent guidance pro-gramme, developed in the USA, that has been shown to reduce behavioural problems in children (39). The programme also led to improvements in children’s behaviour and self-esteem (39).

Preventing youth violence

Programmes that reduce behavioural problems and promote positive parenting skills are targeting risk factors for later delinquent behaviour and violence, and so are likely to prevent them (40). Findings from the 19-year follow-up of a randomised con-trolled trial of the Nurse Family Partnership showed that girls whose mothers received the programme were less likely to enter the criminal justice system than girls in the comparison group, although there did not appear to be any effects for boys (41). This demonstrates that early intervention may prevent later problems.

Research on parenting programmes within low- and middle-income countries

The evidence of parenting programmes’ effective-ness in preventing violence predominantly comes from high-income countries. A recent review did, however, find 12 individual studies from low- and middle-income countries that targeted a range of parenting outcomes, including parent-child inter-action, parent attitudes and knowledge, and harsh parenting (42). These studies reported results that favoured the intervention groups over the compari-son groups, which is very promising. For example, a study of a home-visiting programme in South Afri-ca found that, when their babies were both six and 12 months old, mothers in the intervention group had significantly better relationships with their babies, compared with the comparison group (43). The programme was also associated with a higher rate of secure infant attachment at 18 months old. In a different study, in Pakistan, another parenting programme resulted in a significant increase in the knowledge of and positive attitudes about infant development among mothers in the intervention group when compared with the comparison group (44). This evidence suggests that parenting pro-grammes can improve parenting in low- and middle-income countries (42), despite the likelihood that these parents are facing many other challenges such as poverty and difficult living environments. This being said, few of these evaluations measured actual violence as an outcome, which makes it diffi-cult to draw conclusions about whether or not they would be successful in preventing violence.

In summary, the evidence suggests that parent-ing programmes that encourage safe, stable and nurturing relationships between parents and chil-dren can prevent child maltreatment and childhood aggression. It is less clear whether they can prevent violence in later life. However, by tackling risk fac-tors for violence, it is likely that they have some effect in preventing them. In order to strengthen the evidence base, good-quality outcome evalua-tions of parenting programmes to prevent violence are needed, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

Adapting parenting programmes to other cultures

developed within these countries. Using the same programme in low- and middle-income countries appears to be more popular, because evidence-based programmes are typically evidence-based on high-quality research and are, therefore, more likely to be effective and not result in unintended harm. Also, importing programmes may be less expensive than developing and evaluating new programmes for many different groups (45). However, we can-not assume that evidence-based programmes de-veloped in one context will continue to be effective in other contexts (46). Various factors, including differences in levels of literacy, family structure, how children socialise, values and beliefs, poverty, and pressures such as HIV and AIDS, may affect a programme’s effectiveness. This suggests that pro-grammes may need to be adapted when they are introduced into a new setting.

Cultural adaptation is the process of adjusting a programme so that it reflects the cultural and socio-economic situation of those taking part in the pro-gramme, while keeping it true to the programme’s core elements (45). A very useful step-by-step guide on adapting programmes can be found in the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime’s guide to implementing family-skills programmes for pre-venting drug abuse (http://www.unodc.org/docu-ments/prevention/family-guidelines-E.pdf ) (45).

When considering adapting a programme, an important question is how different the cultures need to be to warrant adaptation (47). This ques-tion is particularly relevant in countries that have many cultures – is it feasible to create an adapta-tion for each cultural group within a country? Gen-erally speaking, cultural adaptation is likely to be necessary if there are poor outcomes when the pro-gramme is delivered as intended, as well as when there are poor participation levels or involvement (48).

Frameworks for culturally adapting evidence-based programmes emphasize four common con-cerns (49).

• The first concern is the need for a balance be-tween staying true to the original programme and adapting it to reflect the differences within the new setting. To increase the chance that an imported programme will be effective in a new setting, the main features responsible for the programme’s effectiveness must be kept, and extensive adaptations should be avoided. • Secondly, a programme must have a solid

pro-gramme theory that clearly specifies the

under-lying mechanisms through which the programme achieves its goals. This allows the programme developers to identify the main features that need to be kept.

• Thirdly, the adapted programme must be evalu-ated to make sure that it is effective in the new setting. Results of monitoring and evaluation should be used to improve the programme where possible, and may show that further adaptations are needed. If further adaptations are necessary, the adaptations must be based on theory and an understanding of the new target group.

• The fourth concern is that the adaptation process should take account of the country’s readiness to implement the programme. Readiness refers to whether or not there is enough knowledge and expertise among the programme staff, ade-quate health and social services, and enough re-sources, including funding, staff and materials, to implement the programme in the new setting. Aside from these concerns, affordability is another consideration when importing programmes into low- and middle-income countries. Many of these programmes are expensive – there are costs asso-ciated with materials, training and support – and many potential purchasers, such as governments and non-profit organisations, are unable to pay the high prices charged for these programmes (49). A potential strategy to tackle this issue is for pro-gramme developers to investigate whether cost waivers or reductions could be made available to promote the importing and cultural adaptation of programmes to these countries (42).

Clearly, it can be challenging to introduce a programme in a new setting. However, despite the significant challenges, programmes have been adapted and implemented in many different cultur-al contexts and maintained their effectiveness (50). It is vital that cultural adaptation is led by theory and research so that the adapted programme can maintain effectiveness as well as being appropriate and relevant for the new target group (45).

The main features of effective programmes

that are likely to achieve positive outcomes, as well as improving existing programmes (52).

General components

Sound programme theory

Programmes are more likely to be effective if they have a solid programme theory (13). As dis-cussed in section 1, a programme theory is the assumptions and expectations about how the pro-gramme should be designed and delivered so that it achieves its aims. It is critical that a programme theory be supported by some empirical evidence or be at least plausible. If it isn’t, a programme will not be effective at achieving its aims, no matter how well it is implemented.

Clearly defined target population

Programmes are more likely to achieve their aims if they have a sound reason for targeting a particu-lar group (53) such as the group’s socio-economic status. This information should be gathered from a formal needs assessment, which identifies the prevalence, nature, and distribution of the problem to be tackled, and investigates whether or not there is a need for the programme (13).

Appropriately timed

Effective programmes are delivered at the time or stage when participants are likely to be most recep-tive to change (54). For instance, programmes for parents of young children can help families avoid behavioural problems in the children when they are older and establish good parent-child relationships (24).

Acceptable to participants

Programmes must be relevant and acceptable to the participants if they are to have positive effects (54). Parents are more likely to get fully involved in a programme and show improvements if they think that the aims of the programme match their goals for themselves and their children in their daily lives (23).

Sufficient sessions

Programmes are more likely to be effective if they involve participants for a sufficient amount of time (54). Typically, the number of hours of involvement will depend on the level of risk of the target popula-tion (24). Programmes with a longer durapopula-tion tend to be more effective at tackling severe problems and high-risk groups. For less severe problems, positive outcomes may be achieved through ‘light

touch’ programmes, such as Selected Triple P (55). This programme consists of three 90-minute semi-nars, with each seminar delivered either as a stand-alone intervention, where parents take part in only that seminar, or as part of an integrated series, where parents attend all three seminars over sev-eral weeks (55).

Well-trained and well-supervised staff

Programmes are likely to be strengthened if they provide staff with sufficient training (54). Training should not only cover the content of the programme, it should also cover the skills needed to involve par-ents actively in the process of change. This includes the importance of empathy, being responsive to families, and respecting individual differences (56). Also, supervising and providing adequate support to staff increases the chance that they will deliver the programme as intended (45, 54).

Most evidence-based parenting programmes are delivered by professionals, which may not be an op-tion within low- and middle-income countries. This is due to the likely shortage of trained professionals in these countries and the cost of professional staff. Evidence suggests that using ‘paraprofessionals’ (including community-development workers and trained lay people) can sometimes be an effective alternative to professionals (57).

Monitoring and evaluation

As discussed throughout this document, a pro-gramme is more likely to be effective, and continu-ously improved, if it incorporates monitoring and evaluation procedures throughout the duration of the programme.

Important components of parenting programmes

Some components are essential to effective par-enting programmes aimed at prevpar-enting or correct-ing behavioural problems (9), which are also likely to be critical for programmes to prevent child mal-treatment:

Opportunities for parents to practise new skills Parents should get a chance to practise the skills that they learn through role-playing, video feed-back and so on. Parents also need to practise new parenting behaviour in their own homes.

Teaches parenting principles, rather than prescribed techniques

– rather than specific responses to certain child behaviours, parents can decide what would work best for them and their children, and learn the skills required to respond positively and appropriately when new situations arise.

Teaches positive parenting strategies, including age-appropriate positive discipline

Programmes must include strategies to handle poor behaviour in a positive and age-appropriate way. Examples of these types of strategies include using time-outs and planned ignoring (which refers to purposefully ignoring a child’s undesirable be-haviour). Alongside these strategies, programmes should include strategies that aim to strengthen positive parent-child relationships through play and praise. This allows for lasting, positive changes in child behaviour.

Considers difficulties in the relationships between adults in the family

In order to achieve long-term improvements in families, difficulties in the relationships between the adults in the family must be considered. It may be beneficial for parents having relationship diffi-culties to attend a parent support programme that deals specifically with these issues.

Summary of section 2

• Evidence suggests that parenting programmes can be effective in preventing all forms of vio-lence, but further research is needed to strength-en the evidstrength-ence, particularly from low- and middle-income countries.

• Importing high-quality parenting programmes may be a more viable option for low- and middle-income countries than developing and testing new programmes.

• When importing programmes, important ele-ments must be maintained but necessary cul-tural adaptations may be required.

SECTION 3

Outcome evaluation:

how do we do it?

To establish whether a programme meets these requirements, the evaluator must determine (58): • whether the programme has a sound programme

theory by evaluating the programme’s history, design and operation. This involves collecting programme documents, and visiting sites where the programme is delivered;

• whether the programme serves the intended target group and whether the programme is de-livered as intended by studying the programme in action. This is particularly important as it may be different to what the programme looks like in theory; and

• whether the programme can provide the neces-sary information for an evaluation by looking at current monitoring and evaluation procedures and deciding whether or not information provid-ed is reliable, as well as whether any other infor-mation will be needed for the evaluation. It will also involve assessing the feasibility of carrying out an evaluation, in terms of available human resources and local capacity.

If a programme is not evaluable, the evaluator will typically direct programme staff to areas that need further development in order to make it evaluable (58). These will also be areas that are likely to strengthen the programme even before the evalu-ation, as well as improve its capacity to report ac-curately on its activities. Evaluability assessment can also improve a future evaluation by getting agreement, between the evaluator and programme staff, on what is important in the programme, antic-ipating problems that may arise during evaluation, and making sure that the overall process will run smoothly (58).

Assessments of evaluability can be carried out by a member of the programme staff who is expe-This section begins with an outline of the main

ac-tivities that need to be carried out before an out-come evaluation. It then discusses the steps that take place during the actual evaluation. This sec-tion does not provide specific guidance on how to carry out an evaluation, but it enables an under-standing of the processes. Although outcome eval-uation can only be carried out on programmes that are up and running, it is useful for staff involved in developing a programme, or in the early stages of implementing one, to think through how they will assess its effectiveness.

Activities before an evaluation

The activities that need to be carried out before an outcome evaluation are:

• evaluability assessment; • budgeting for evaluation; and • choosing an evaluator.

Evaluability assessment

Planning and carrying out a high-quality outcome evaluation takes time and money. If a programme is already running it is valuable to know whether or not it is ready for an outcome evaluation – in other words, is it ‘evaluable’?

A programme is likely to be evaluable if it (58): • has a sound programme theory;

• actually serves the intended target popula-tion;

• has a clear and specified curriculum and is delivered as intended;

• has realistic and achievable goals;

• has the resources discussed in the pro-gramme design; and

rienced in evaluation. However, it is highly recom-mended that they are carried out by an external evaluator.

Budgeting for an evaluation

A portion of a programme’s budget must be dedi-cated to monitoring and evaluation activities, including outcome evaluation. Although the fund-ing set aside for an outcome evaluation is likely to change as details of the evaluation process become clearer, it should be considered as part of the ini-tial planning process (59). Below are some of the expenses associated with an outcome evaluation (59):

• fees of the external evaluator and other eval-uation staff (for example, fieldworkers who interview parents);

• evaluation team’s travel expenses;

• communications (for example, phone calls, internet access);

• general supplies (for example, stationery); • costs of producing items for collecting

infor-mation (for example, questionnaires); • printing and copying costs; and

• office space and other space for evaluation activities.

Programme managers may benefit from creating an evaluation budget which sets out the amount of time needed for the evaluation, as well as the costs and resources (59). The amount of time needed for an evaluation will depend on the questions that need to be answered, the available resources, as well as other external factors (59). Timing must be considered to ensure that the evaluation is feasi-ble and will produce accurate, reliafeasi-ble and useful results.

Choosing an evaluator

Many monitoring and evaluation activities can and should be performed by programme staff on a reg-ular basis. However, it is highly recommended that a programme uses an external evaluator to carry out outcome evaluations in order to increase the likelihood that the evaluation will be unbiased (14). Even if an evaluation is well-designed, if it is carried out by programme staff, the question will always arise as to whether staff were biased, knowingly or unknowingly, towards showing the programme in a positive light (14). Using an external evaluator makes sure that the results of the evaluation will be seen as credible. Also, an external evaluator may share different perspectives and knowledge that

could be helpful to the programme as a whole (13, 14).

There are different ways to choose an external evaluator. Programmes that have already been evaluated may be able to recommend an evalua-tor. Certain university departments (such as public health, psychology or social work) may be interest-ed in evaluating parenting programmes (26). Some universities run initiatives that aim to connect uni-versity staff and students interested in evaluation with community organisations wanting evaluation services. People with evaluation expertise may be willing to consult programme staff or carry out an evaluation, but they typically expect some form of payment for their services (26). For instance, pro-fessional consultants will generally charge for their services, while a university department may want to publish the evaluation results (26).

Below is a list of some key characteristics nec-essary in an evaluator (26). The evaluator:

• must not be directly involved in developing or delivering the programme being evaluated; • must not respond to any pressure from staff

to produce certain findings;

• must be able to see beyond the evaluation to other programme activities;

• must be appropriate for the organisation and be able to listen carefully to the concerns about and goals of the evaluation.

As well as choosing the lead evaluator, a pro-gramme needs to assess its own staffing levels be-fore starting an outcome evaluation. Local staff will be needed during the evaluation (for example, to co-ordinate the evaluation, conduct interviews and so on).

The outcome evaluation process

When a programme is evaluable, has a budget for an outcome evaluation, and has chosen an exter-nal evaluator, it is ready for the outcome evaluation process to start. According to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention evalu-ation framework (ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Publica-tions/mmwr/rr/rr4811.pdf) (60), the steps of the evaluation process are:

1. engage stakeholders; 2. describe the programme; 3. design the evaluation; 4. gather credible evidence; 5. justify conclusions; and

1. Engage stakeholders

The first step in the evaluation process is to engage evaluation stakeholders. These are the people or organisations that have an interest in the results of the evaluation and what the result will be used for. Stakeholders include, among others, donors, programme staff, government officials and people participating in the programme. Engaging stake-holders ensures that their views on the programme are understood. The evaluation can then reflect these views and the findings may be more accept-able to stakeholders. Once engaged, stakeholders may also provide various forms of help to the evalu-ation team during the evaluevalu-ation process.

2. Describe the programme

Programme staff and other stakeholders should come up with an agreed description of the pro-gramme, in terms of the need for the propro-gramme, expected outcomes, programme activities, resourc-es, the context of the programme, the programme theory and so on. This description should be based on the original programme planning and design where goals were set. Through this process, stake-holders can establish the main aims to be evalu-ated. Stakeholders must agree on the programme description, otherwise the evaluation is likely to be of limited use.

3. Design the evaluation

Choosing the evaluation design – At this point, the evaluation design needs to be chosen. This choice will depend on various factors, including how long the programme has been running, avail-able resources and ethical considerations, such as whether it is appropriate to use a control group that does not get the programme. Programmes should choose the most scientifically rigorous evaluation design possible, bearing in mind these factors.

Choosing a sample – Once the design has been chosen, a ‘sample’ of parents needs to be chosen. A ‘sample’ refers to a subset of a whole group (for ex-ample, a subset of parents with children aged three to eight years) which is studied and whose charac-teristics can be generalized to the entire group of interest (27). Choosing the sample size is a com-plex activity and a statistician should be used to produce a ‘power calculation’, which indicates how many participants are needed in the evaluation in order to show the predicted improvement.

The goals of the evaluation will largely deter-mine which parents or children are chosen to be including in the evaluation (61). For example, when

wanting to determine the general effectiveness of a programme, random samples of all parents who enter the programme during a specific time period should be chosen. Alternatively, if the objectives concern particular types of parent (for example, high-risk mothers), then random samples should be chosen to represent this specific group. If the objective is to compare one programme against another, then similar types of parent should be recruited from each programme. The method of choosing a sample should be described in the eval-uation report so that others can understand the rationale for choosing certain parents for participa-tion, as well as the potential biases which may stem from this (61).

Choosing and measuring outcomes – When choosing the outcomes to evaluate, a thorough review of the programme theory may be helpful as it most likely differentiates between short-term (parents know more about positive discipline), in-termediate (parents use positive discipline strate-gies) and long-term outcomes (reduction in rates of child maltreatment). Careful discussion with stake-holders should go into choosing outcomes to be measured. It may be the case that outcomes were decided upon when applying for funding.

It is not usually necessary to measure all out-comes as some are more important than others. Also, very long-term outcomes are often the most difficult and expensive to measure, and it may not always be feasible to include them in the evalua-tion (13, 14). For example, Caring Families, which is for parents of children age three to eight years, has an aim that the children will be less likely to get arrested by the age of 20. However, it will be ex-pensive and difficult to track these children for that long. It may be more feasible to measure short-term and intermediate outcomes, such as levels of child behaviour problems and the strength of the parent-child relationship.

An outcome evaluation is likely to be strength-ened by using multiple measures. This counteracts possible weaknesses in one or more of the mea-sures, to provide a more accurate picture of what the programme has achieved (13, 45). Unfortu-nately, the more measures that are used, the more expensive the evaluation will become (because translating the measures, if necessary, training staff in the measure and staff time for interviewing participants will all cost more), and the greater the probability that one or more of the measures will show a significant effect by chance.

direct measures, proxy measures and changes in risk factors. Examples of each of these in the con-text of parenting programmes aimed at preventing violence are provided in Table 1 above.

Ideally, programmes should use direct mea-sures, such as reports from child protection ser-vices, as they allow the most accurate conclusions to be drawn. However, a concern with this type of measure is that violence, especially against chil-dren, often goes unreported. So if the measure used is reports from child protection services, the problem may seem less severe than it really is.

Direct measures may not be suitable for some low- and middle-income countries where child-protection services may not exist or may not be well-developed. Proxy measures, such as visits to the emergency department, may also be a problem for the same reasons as using reports from child-protection services.

As an alternative, many outcome evaluations assess changes in risk factors, such as a parent’s attitudes towards discipline. If risk factors are as-sessed, it is usually best to use measurement in-struments that are standardised – this means that they have been designed to be administered, scored and interpreted in a set way. Using standardised in-struments increases the validity of the evaluation, which means that the findings are more likely to be

credible (see Table 2). Many of these rely on ‘self-reports’ by parents, which may, however, be vul-nerable to bias. Others are based on observing and coding the behaviours of parents and children while they work through various tasks in their home or in an observation room in a clinical setting. Two ex-amples of observational instruments are the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) Inventory (62) and the Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System (DPCIS) (63).

If the instrument is in a different language than that which is spoken by the sample, there may be issues with translation. Incorrect translations may reduce the instrument’s accuracy. So it is best to choose instruments that are in the same language as that used by the sample. If this is not possible, translation followed by back translation is a useful alternative.

Choosing and measuring outcomes requires planning and consideration. If appropriate out-comes and measurement methods are used, the findings of the evaluation are more likely to be cred-ible and useful to stakeholders.

Follow-up – In order to determine whether or not the changes (if any) identified in participants were maintained over time, it is necessary to moni-tor the sample of parents for some time after the programme has ended. This is particularly

impor-Table 1. Examples of direct measures, proxy measures, and risk factors.

Direct measures Proxy measures Changes in risk factors

Reports from

child-protection services • • Hospital admission ratesVisits to the emergency department (especially for accidents and injuries)

• Child being placed in care outside the home

• Parent-child attachment behaviour

• Parental attitudes toward child

• Use of positive discipline

• Parental responsiveness

[image:23.595.75.524.87.167.2]• Parental stress

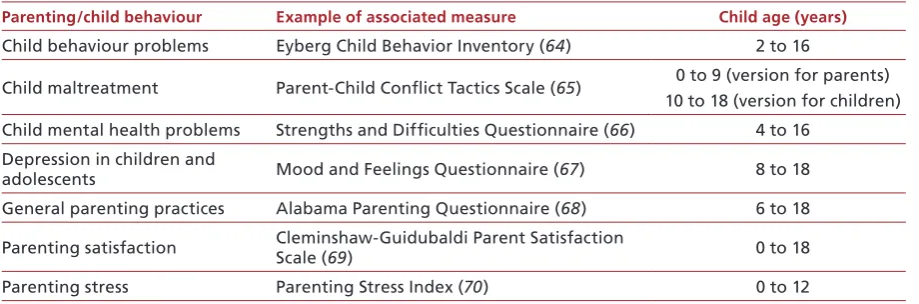

Table 2. Examples of common standardized instruments.

Parenting/child behaviour Example of associated measure Child age (years)

Child behaviour problems Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (64) 2 to 16

Child maltreatment Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale (65) 0 to 9 (version for parents) 10 to 18 (version for children) Child mental health problems Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (66) 4 to 16

Depression in children and

[image:23.595.70.530.606.758.2]tant if the main aim of the programme is to reduce future risky behaviour from children. A number of the programmes endorsed as Blueprints for violence prevention programmes (http://www. colorado.edu/cspv/blueprints/) have recently been downgraded because they have not yet shown effectiveness over the long term.

4. Gather credible evidence

Information should be collected systematically and impartially. If the information gathered is credible, the findings of the evaluation are more likely to be useful, and recommendations that stem from the evaluation are strengthened. If there are any doubts about the quality of information and the conclusions drawn from it, programme staff should discuss these with experts in designing evalua-tions.

5. Justify conclusions

Once the evaluation findings have been compiled, stakeholders must agree that the conclusions are justified. To do this, the conclusions must be linked to the information gathered and judged against agreed values or standards set by the stakehold-ers. This will help to make sure that the evalua-tion is useful to (and used by) those running the

programme, and will help to validate the results. It is often useful to form an exper