15 Inequality and rising levels of

socio-economic segregation

Lessons from a pan-European

comparative study

Szymon Marcińczak, Sako Musterd,

Maarten van Ham and Tiit Tammaru

Abstract

The Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities: East Meets West

project investigates changing levels of socio-economic segregation in 13 major European cities: Amsterdam, Budapest, Vienna, Stockholm, Oslo, London, Vilnius, Tallinn, Prague, Madrid, Milan, Athens and Riga. The two main conclusions of this major study are that the levels of socio-economic segregation in European cities are still relatively modest compared to some other parts of the world but that the spatial gap between poor and rich is widening in all capital cities across Europe. Segregation levels in the East of Europe started at a lower level compared to the West of Europe, but the East is quickly catching up, although there are large dif-ferences between cities. Four central factors were found to play a major role in the changing urban landscape in Europe: welfare and housing regimes, globalisation and economic restructuring, rising economic inequality and historical development paths. Where state intervention in Europe has long countered segregation, (neo) liberal transformations in welfare states, under the influence of globalisation, have caused an increase in inequality. As a result, the levels of socio-economic segrega-tion are moving upwards. If this trend were to continue, Europe would be at risk of slipping into the epoch of growing inequalities and segregation where the rich and the poor will live separate lives in separate parts of their cities, which could seriously harm the social stability of our future cities.

Introduction

sense may suggest that greater inequality in a city also entails higher levels of socio-economic segregation (Reardon and Bischoff 2011). Nonetheless, more often than not, the relation between the two is far from ‘positive’ and ‘linear’. The seemingly obvious and logical regularity of this relation is mediated by a country/region-specific institutional setting and a city’s trajectory of economic and population development (Burgers and Musterd 2002; Maloutas and Fujita 2012; Musterd and Ostendorf 1998). Moreover, socio-economic segregation will also be mediated by other forms of segregation, such as race-based and ethnic segregation (van Ham and Manley 2009; Manley and van Ham 2011). When a household ‘selects’ a certain place to live on demographic or cultural grounds, there will also be an impact on segregation in socio-economic terms. Viewed in this light, the studies on class-based spatial divisions in a selection of European cities brought together in this volume illuminate the complex relations between economic inequality, social disparities, and urban space. These relations unfold in the divergent historical, demographic, cultural and institutional contexts of the northern, southern, western and eastern parts of Europe at times of profound political and economic changes. Sweeping across the continent in the last two decades, these changes include the fall of the Berlin Wall (1989) and demise of the Soviet Union (1991), the enlargement of the European Union to include the new member states from East Europe1 in 2004 and 2007, a concomitant massive East–West migration and, more recently, a deep economic crisis and its aftermath.

After an era of decreasing social inequality, which effectively started after World War II, from the early 1970s onwards, income inequality has been con-tinuously increasing across the globe. In Europe, wealth inequalities are currently almost as high as they used to be in the heydays of laissez-faire capitalism in the late nineteenth century (Piketty 2013). Interestingly, one and a half centuries ago, similar levels of inequality were related to the formation of dreadful slums (Booth 1887, 1888; Engels 1892) and to clear-cut spatial divisions between the rich and the poor in the great industrial cities of that epoch (Park et al. 1925; Zorbaugh 1929). In the early 1990s, when globalisation was thriving and a new global divi-sion of labour evolved, some scholars predicted similar scenarios for urban areas at the turn of the twenty-first century. In brief, the end of the second and the begin-ning of the third millennium were heralded to be the advent of the era of mounting inequality, increasing class segregation and concentrated affluence and poverty (Massey 1996).

360 Szymon Marcińczak et al.

Watson 2009), in West Europe and other western countries (Maloutas and Fuijta 2012; Musterd and Ostendorf 1998) or, recently, also in East Europe (Marcińczak

et al. 2015). The contributions from 13 major European cities collected in this volume – Amsterdam, Budapest, Vienna, Stockholm, Oslo, London, Vilnius, Tallinn, Prague, Madrid, Milan, Athens and Riga – reveal that the levels of socio-economic segregation are moving upwards, and that the spatial gap between the more extreme socio-economic categories is widening in all capital cities across Europe.

The lack of studies that compare and contrast processes and patterns of socio-economic segregation is in fact surprising as the field of urban studies is currently witnessing a revival and a reorientation of comparative research (McFarlane and Robinson 2012; Robinson 2011; Ward 2010). Essentially, this reinvigorated strand of urban studies aims at the systematic study of similarity and difference among cities or urban processes both through description and explanation (Nijman 2007). Even if the chances for a methodologically rigorous case selection are fairly slim (Kantor and Savitch 2005; McFarlane 2010; Pickvance 1986), comparative urbanism emphasises the merit of a cyclical movement between theorising and doing empirical research. This offers a unique opportunity to review established theories and to avoid further development of decontextualised universalist ideas and models of urban development (Robinson 2011).

The rest of this chapter is divided into three main sections. The first section summarises the changing patterns of socio-economic segregation in political and/ or economic capital cities of Europe in the first decade of the new millennium. In the introductory chapter of the book (Tammaru et al. 2016b) we presented a multi-factor approach to understanding segregation that resulted in the following theoretical ranking of cities with regard to their expected level of socio-economic segregation: London; Riga; Madrid and Vilnius; Milan and Tallinn; Amsterdam and Athens; Budapest, Oslo and Stockholm; and finally Prague and Vienna. The case studies presented in this book revealed a somewhat different ranking based on real data: Madrid and Milan; Tallinn; London; Stockholm; Vienna; Athens; Amsterdam; Budapest; Riga; Vilnius; Prague; and Oslo. In this concluding chap-ter we will elaborate on the differences between the theoretical and actual rankings of cities, mainly by scrutinising the similarities and differences in the levels and geographies of class-based spatial-disparities in our case cities. In the following section we elucidate how globalisation, economic inequality, different housing regimes and forms of welfare state relate to patterns of socio-spatial divisions in our selection of European cities. In the third and concluding section, we summa-rise the most important findings in the perspective of the multi-factor approach we developed in the introductory chapter of this volume.

Class and space in the European city

362 Szymon Marcińczak et al.

[image:5.442.66.367.356.519.2]top (high) and bottom (low) social categories, as well as different spatial units, may influence the values of segregation measures. Notwithstanding the limi-tations of available data, it is clear that the rule that higher classes are more segregated than the lower classes is not ubiquitous. Even if in two-thirds of 12 European capital cities, the higher class is the most segregated social category (in Amsterdam, Stockholm, Oslo, Vienna, Madrid, Tallinn, Riga and Vilnius), the remaining cases show other outcomes. In Athens2 and London, a counterintuitive segregation profile has been present for the last two decades. The ‘anomaly’ has been fading out in Budapest, but it has become a clear pattern in Prague. We must take into account that these differences between cases may be an effect of scale: the use of either cities or the whole metropolitan area. Essentially, metropolitan areas represent a spatial scale that allows more variation within its boundaries than a city does, for example concentrations of the affluent in inner London and more dispersed concentrations elsewhere in greater London can exist simultane-ously. The stronger segregation of lower social groups could also result from inherited morphological structure and housing inequalities. But maybe also suburbanisation draws higher social echelons out of previously socially mixed neighbourhoods, as seems to be the case in Budapest and Prague. In other words, irrespective of the apparently unifying effect of neo-liberalisation and globalisa-tion, the institutional, economic and demographic contexts still play a key role in determining which end of the social hierarchy is more segregated. The general conclusion about the shape of the distribution of segregation by social category is that profiles reported in 12 cities are skewed and that in most but not all cases, the highest social strata appear to be the most segregated.

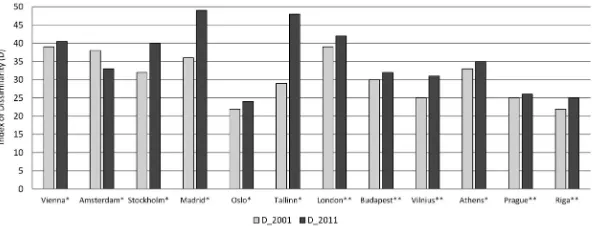

Figure 15.1 Index of segregation scores for top and bottom social categories.

Notes: * Metropolitan region, **city

Madrid, Tallinn, London, Budapest, Vilnius, Athens, Prague, Riga – managers and elementary occupations.

Figure 15.1 shows index of segregation scores for top and bottom social categories for 12 cities for both 2001 and 2011. There is a substantial difference between the levels of socio-economic segregation in our European case cities. In general, whereas in the early 2000s it was still possible to argue that West European cities were more segregated than those in the East, a decade later this is no longer so obvious. Most importantly, the intensity of socio-spatial divisions and its changes have not followed any clear regional pattern (Figure 15.1). The levels of segregation of the top and of the bottom categories decreased in Amsterdam (but see below). In Vienna and Prague (limited) desegregation was confined to the top social categories only, but we should take into account that the segregation level of the top social class in Vienna was already very high in 2001. In London and Budapest only the lower social groups became more evenly distributed; here we notice that segregation levels of the lowest class in London were already very high in 2001. Socio-economic spatial divisions of the social ‘top’ (relative to the rest) and ‘bottom’ (relative to the rest) became more pronounced in the other seven cities (Stockholm, Oslo, Madrid, Athens, Tallinn, Vilnius and Riga). The rise of segregation was especially high in Stockholm, Tallinn and Madrid. Interestingly, the recent crisis seems to contribute to both increasing segregation (Madrid) and desegregation (Amsterdam). In the latter case, the crisis implied a dynamic that was against the processes that were going on before and that created more segregation. Due to the crisis, people did not dare to make big (residential) decisions anymore; this resulted in (likely temporary) reduced segregation levels. In addition, there were swift changes in the formerly nineteenth-century neigh-bourhoods in Amsterdam that created – temporarily – more mix. Therefore, in a more structural sense segregation also seems to be increasing in Amsterdam. However, segregation also increased in Madrid also during the crisis. Here it seems that the crisis strengthened the segregation processes that were already ongoing: the poor became poorer in the neighbourhoods where they already lived; and the rich were able to retain their wealth, largely because the higher managerial and professional ranks managed to cope with the effects of the crisis. Moreover, Madrid only recently started to weaken the impact of family solidarity networks, networks requiring spatial proximity between different social classes and gen-erations (Allen et al. 2004), implying that segregation could increase due to that process too. Also, gentrification started late in Madrid, and therefore the initial desegregating effects, which usually can be seen in the early phases of gentrifica-tion (cf. Freeman 2009; Galster and Booza 2007), are still negligible. Overall, for 9 of the 12 cities we had information on, we find increasing levels of segregation of the top social categories; and also for 9 of the 12 cities we found increasing segregation of the lowest social categories. Amsterdam may perhaps be added to these latter 9.

364 Szymon Marcińczak et al.

Milan scholars point at demographic processes that are driving declining segregation: (1) gentrification leading to the substitution of working-class households in working-class neighbourhoods by white-collar workers; (2) under right-to-buy schemes working-class households purchased properties which they subsequently sold to collar households; (3) upgrading through inheritance, where a white-collar children inherit a house from their working-class parents; (4) the tendency for self-employed households on modest incomes to settle in the working-class periphery of the city where housing is affordable and where public and state-subsidised housing is mainly located. In other words, it seems that there are two general factors that appear to reduce levels of segregation, possibly both only temporarily. One is a limited or reduced level of residential mobility that leads to in situ social mobility: sitting residents become richer or poorer in their neighbourhoods. That creates more mix in situ and thus lower levels of segregation (cf. Galster and Booza 2007). When residential mobility increases again, we should see rising levels of segregation. The second factor is gentrification. Especially when gentrification is new in an area, this is typically a process where formerly homogeneous low-income households become accompanied by socially upward neighbours. This will initially reduce the level of segregation. More mature gentrification may again result in increasing segregation.

It would be misleading to attribute all changing levels of segregation to the effects of the crises and/or demographic processes only; these forces will be responsible for temporal deviations of the more general and structural changes in some cities, but not in all. The mounting socio-economic spatial disparities in Tallinn, a city that has also been in the grip of the recent economic crisis, may well have other roots. It is likely that the significantly higher levels of socio-spatial divisions in Tallinn in 2010 stem from the realised potential of the rapidly grow-ing income inequality and employment change in the 1990s. Segregation has been on the rise in most of the other East European cities too. Essentially, while eco-nomic disparity skyrocketed throughout the region, the patterns of segregation did not change much in East Europe in the first decade after the collapse of socialism (Marcińczak et al. 2013, 2014; Sýkora 2009). However, from the second decade onwards, inequalities started materialising in space. Finally, institutional arrange-ments, housing regimes and the extent of the welfare state have had a tremendous impact on socio-economic segregation. In countries that virtually did not suffer from economic turmoil, levels of segregation either decreased somewhat (higher social strata in Vienna), or, as the case of Stockholm clearly exemplifies, increas-ing segregation could be observed before and after the crises. We will discuss the nexus between institutional arrangements, economic inequality and socio-economic segregation in the next section.

economic and housing crisis, which hit Amsterdam particularly hard, the separa-tion between the rich and the poor also increased in Amsterdam, as shown in this volume. The reduced levels of segregation of the ‘top’ relative to the rest, or the ‘bottom’ relative to the rest (reported above for some cities), does not prevent increasing separation of the ‘top’ from the ‘bottom’. This indicates that although socio-economic residential mixing may occur, this is limited to groups with a status that is not too far apart from each other. This corroborates the findings by Musterd et al. (2014), who showed that the tendency to move increases with the social distance between an individual and the social level of the neighbourhood (s)he is living in; larger social distances imply a larger propensity to move and subsequently a larger chance to end up in a socially more similar neighbourhood. However, the spatial gap between the more extreme categories, those that ‘have’ and those that ‘have not’ is pretty much widening all over Europe. However, so far, the socio-economic segregation is clearly lower than in the USA (Florida 2014) or in Brazil (Villaca 2011).

[image:8.442.57.353.65.178.2]The ethnic and socio-economic dimensions of segregation are often linked. Even if the two dimensions do not overlap completely, immigrants in the West European countries, especially those newly arrived, are frequently overrepresented among the urban poor (Arbaci 2007). Yet, there is also class differentiation within categories of native and non-native residents. Some cities (Amsterdam, Stockholm) show that such class differentiation is even bigger for some non-native categories than for the native categories. Strong social divisions underpinned by ethnic disparities do not necessarily have to be a consequence of recent immigration. The Baltic States, principally Estonia, demonstrate the effect of deeply rooted ethnic divisions amplified by the downfall of social-ism and the formation of independent statehood in the early 1990s. In Tallinn, the divisions between higher-class natives and lower-class minority groups are higher than in any other European city where ethnic divisions are present; such

Figure 15.2 Index of dissimilarity.

Notes: * Metropolitan region, **city

Madrid, Tallinn, London, Budapest, Vilnius, Athens, Prague, Riga – managers and elementary occupations. Amsterdam, Oslo, Stockholm – highest and lowest income quintile.

Table 15.1

Major areas of concentration for top and bottom social groups in selected European cities, 2001–201

1

City/r

egion

Comments

Amsterdam

High SES is over

-represented in some older neighbourhoods in the inner city and in specific suburban areas. Low SES is over

-represented

in post-war social housing neighbourhoods and in some of the older parts of the core city where social housing is prevalent.

Athens

Traditional social division between Low SES west and High SES East shapes

Athens since the nineteenth century

. Over the last decades, High

SES is opting massively for residence in the north-eastern and south-eastern suburbs, creating strong city–suburb SES divide.

Budapest

Clear social division between High SES west sector stretching from the city centre to the suburbs, and the rest of the city

. Three Low SES areas

stick out: some decaying inner

-city quarters, socialist high-rise housing estates and low-rise suburban residential-industrial neighbourhoods.

London

The High SES west and Low SES east is the most important macro-level social division already existing for centuries.

A

sector of High

SES extends from west-central London towards the suburbs. Low SES location pattern is more mosaic compared to High SES, and concentrations can mainly be found in the distant suburbs.

Madrid

High SES is expanding from the core city towards the suburbs, especially to the north and north-west, creating clear divisions

between

the core city and suburbs.

Those High SES who inherited, or who succeeded the prior inhabitants, stay in the core city

. Low SES has

long been over

-represented in the core city and in the suburbs in the south and east.

Oslo

A

key social division runs between the High SES west and the Low SES east.

There are many locations in the city

, however

, where

concentrations of both social groups are juxtaposed with each other

.

Prague

Many locations in the city show concentrations of High SES and Low SES that are often juxtaposed all-over the city

. A

typical

socio-spatial mosaic.

Stockholm

High SES is over

-represented in inner

-city neighbourhoods and in specific suburban areas. Low SES is over

-represented in more

peripheral post-war social housing neighbourhoods.

T

allinn

High SES predominates in the historical city centre and attractive inner

-city neighbourhoods from the 1930s. Low SES is

overrepresented in the socialist-era housing estates and in seedy

, pre-W

orld

W

ar II neighbourhoods in the inner city

. In the periphery

,

High SES and Low SES concentrate in non-conterminous sectors and clusters.

V

ienna

High SES residential patterns is sectoral, stretching from the western inner

-city districts to the western outskirts of the city

. Low SES

are over

-represented in the eastern parts of the city and strongly confined to public housing neighbourhoods

.

V

ilnius

Historical north–south division of the city is deepening. High SES is over

-represented in the inner city and low-density villa areas in the

outer city

. Low SES is strongly over

-represented in the south, especially in older socialist housing estates, as well as in the most

peripheral parts in the north.

Riga

High SES concentrates in the city centre (historical core) and in small clusters sprinkled over the peripheral areas. Low SES a

re

overrepresented in the lower quality housing in the inner

-city and in the periphery

. Both social categories mix in the socialist-era

a scale of disparities, arguably, evokes the picture of clear-cut ethnic/racial divi-sions epitomised by urban regions in the USA (Farley et al. 1978; van Kempen and Murie 2009).

Table 15.1 gives an insight into the major areas of concentration for top and bottom social groups in 12 cities. The descriptions in the table and the figures show that the geography of socio-economic segregation in European cities does not follow a uniform model. The only general characteristic shared by all 13 cit-ies was a mosaic socio-spatial structure of the urban fabric. In the last 10 years this inherent feature of socio-economic spatial divisions in the European city (French and Hamilton 1979; Marcińczak et al. 2015; Musterd 2005) has some-what changed. In the first decade of the twenty-first century we can now see emerging a more regular, often sectorial, pattern of socio-economic segregation in many cities. In short, the seemingly mosaic pattern of social disparities con-ceals divergent, context-sensitive, local patterns of class segregation (Table 15.1). In cities like Stockholm, London and Amsterdam, urban-oriented fractions of the middle class and certain professions increasingly concentrate in the central parts of the metropolitan area and the poorer households are consistently more dependent on housing in more peripheral residential areas. Social mix and anti-segregation policies may have reduced this process but failed to stop the overall trend. Interestingly, London is an excellent example of how persistent the legacy of historically developed segregation patterns might be: the social status of some neighbourhoods has not changed much for more than a century (Manley and Johnston 2015). The geographies of class divisions in Budapest and Vienna also point towards an important role for an ‘inherited’ urban fabric. Even though the two cities developed in radically different economic and political milieus in the second half of the twentieth century, higher social categories still occupy bour-geois tenements and villas, and lower classes are overrepresented in poor-quality buildings that housed the working class in the last days of the Habsburg Empire.

368 Szymon Marcińczak et al.

Economic disparities, globalisation, institutions and segregation

The starting point for this study was the multi-factor approach which we presented in the introduction of this volume (Tammaru et al. 2016b). This approach resulted in a theoretical ranking of our case study cities by the level of socio-economic segregation. Referring to theories explaining patterns of socio-economic seg-regation, the multi-factor approach lists a number of ‘universal’ and ‘relative’ characteristics determining levels and geographies of social divisions. The ‘universal’ factors are believed to cause ubiquitous effects that are not sensitive to spatio-temporal parameters, whereas the ‘relative’ factors are highly specific to particular social systems (Pickvance 1986). As a more parsimonious approach might still be beneficial for meaningful comparative analysis (Kantor and Savitch 2005), we selected four key variables for further examination. Essentially, we chose two universal factors (income inequality and level of globalisation) and two contextual factors (housing regimes and forms of the welfare state) to elucidate the complex relations between important structural economic and insti-tutional changes and evolving patterns of residential segregation we encounter in European cities. We present a series of bivariate analyses of the relations between spatial separation of opposing social groups and the key contributory factors.

In general, it is taken for granted that socio-economic segregation is a product of socio-economic inequality, and that growing inequality results in increasing segregation (Massey 1996; van Kempen 2007; Watson 2009). However, the appar-ently universal and strong correlation between social and spatial divisions is not always existing (Fuijta 2012). In brief, the catalysing effect of income inequality on residential segregation hinges on context-specific institutional arrangements: for instance, a close and lasting link between segregation and inequality requires the presence of an income-based housing market and housing policies that relate income to residential location (Brown and Chung 2008; Reardon and Bischoff 2011). The results from the analysis of our 13 European cities shed some new light on these relations.

was consistently growing in the 1990s that may actually point to the lagged effect of income disparities on residential segregation; it simply takes time before spa-tial patterns catch up with socio-economic changes. Interestingly, a temporarily reversed relationship between economic inequality and segregation is also pos-sible; in East Europe, rapidly growing income disparities after the collapse of socialism entailed short-term desegregation in the 1990s (Marcińczak et al. 2013: 2014; Sýkora 2009). A fairly similar trend could also be found outside former socialist Europe (Oslo in the last decade of the previous century). In fact, such a long-term perspective on the relation between social inequality and the level of socio-spatial segregation also proves to be more relevant for almost all of the cities included in this study. In that respect it is also important to filter out the temporary or conjunctural effects. With a view on social inequality over a longer period of time, we can show, for example, that Amsterdam (and the Netherlands) experi-enced substantially growing inequality over the past three decades, which also resulted in increasing socio-spatial segregation until 2008 when the crisis started. In 2011, compared to the start of the millennium, social inequality dropped a little, but compared to the late 1980s social inequality rose significantly. The more recent drop coincided with lower levels of segregation, which were also to be ascribed to the crisis. If crisis effects are left out, economic inequality has been on the rise for the last two or three decades.

Figure 15.3 Income inequality and residential segregation between top and bottom social categories in selected European cities, 2001/2004–2011.

Notes: * Metropolitan region, **city.

Madrid, Tallinn, London, Budapest, Vilnius, Athens, Prague, Riga – managers and elementary occupations. Amsterdam, Oslo, Stockholm – highest and lowest income quintile.

370 Szymon Marcińczak et al.

Even if the widening spatial gap between the top social class and the bottom social class generally correlates with a growing economic inequality, as can be shown for 9 out of 12 cities, it does not necessarily mean that the most unequal cities are also the most segregated. Stockholm, the capital of one of the most equal countries in the world, is – at the moment – relatively high in the hierarchy of socio-economic segregation in Europe. Most important, the relationship between segregation and inequality is rarely linear. In other words, a relatively small increase in income inequality may relate to significantly growing residential segregation (Madrid, Stockholm). On the other hand, a more substantial growth of socio-economic disparities may well coincide with a negligible increase in residential segregation (Budapest, Prague). Thus, social inequality is not sufficient as the sole explanatory factor of the evolving patterns of residential segregation in Europe.

The globalisation of the economy and society and a series of massive and par-allel changes that the processes involve, have been argued to stimulate the growth of socio-economic disparities and segregation in the contemporary city (Fainstein

In short, the future of cities is partly conditioned by the historically created eco-nomic profile of the city and the level of integration in the global economy. This may or may not lead to increasing social disparities, mismatches, social polarisa-tion or duality (Castells 1989). Yet, even cities that manage to get a strong posipolarisa-tion in global networks will not automatically become the most segregated cities (Butler and Hamnett 2012); logically, actual social and spatial divisions are highly complex (Marcuse 1989; Hamnett 2012). Nevertheless, for some cities, globalisa-tion brought about growing socio-economic inequalities (van Kempen 2007) and, at least in the USA, also more intensive spatial segregation (Fischer et al. 2004; Reardon and Bischoff 2011). In other cities existing economic structures did not suit the globalisation processes. This may have resulted in mismatches between demand and supply of labour, but may also have triggered active professionali-sation policies, increasing professional skills throughout the social distribution, therewith reducing the share of lower strata while increasing the middle and upper strata. According to many, professionalisation, not polarisation, has in fact been the main trend in the transformations of employment profiles in European cities. The pattern that was clear in Europe already in the 1980s (Hamnett 1994), and that seems to have become even more prominent in the 1990s (Butler et al. 2008; Maloutas and Fujita 2012; Marcińczak et al. 2014, 2015; Préteceille 2000), may not have changed too much in the first decade of the new millennium, although there is difference between cities. In short, we expect a relationship between the ‘global’ character of a city and the level of social polarisation that will also be reflected in spatial segregation between top and bottom, but that relationship can be mitigated by a range of other forces.

It is hard to quantify such a multidimensional phenomenon as globalisation. We refer to a well-known typology of cities that reflects a city’s connection with the global economy (Beaverstock et al. 2014) to differentiate between European cities that are more embedded in the space of flows and those that are less. There are three groups and several subcategories of world cities: Alpha cities link major economic regions and states to the world economy; Beta cities link their region or state to the world economy; and Gamma cities connect smaller regions or states to the world economy (Beaverstock et al. 2015) Figure 15.4 shows the relationship between world-city status and residential segregation between top and bottom social groups.

The European cities examined in this study virtually represent all categories distinguished by the world-cities taxonomy; major European urban areas range from the iconic Alpha++ global cities like London to the much-less integrated capital cities of the Baltic States. Then, what do we see when we relate the clas-sification based on this indicator of globalisation with the level of segregation of the cities studied in this volume? And how does that relation change over time?

372 Szymon Marcińczak et al.

areas (Florida 2014). However, we also see that Tallinn is, in fact, an outlier when it comes to the relation between globalisation and segregation. It used to be mod-erately socio-economically segregated like other East European cities but became highly ethno-linguistically segregated under socialism (Marcińczak et al. 2015; Tammaru and Kontuly 20101). What has happened in Estonia over the past two decades is a growing overlap between ethnic and socio-economic segregation, driven by marked occupational differences between the members of the minor-ity and majorminor-ity population in very market-driven social and housing contexts that may easily translate income differences into spatial differences (Tammaru

et al. 2016a). Apart from Tallinn, there appears to be a firm relation between the ‘global’ position and the level of segregation between the ‘top’ and the ‘bottom’ of the social distribution (Figure 15.4). Lower levels of segregation go along with a more moderate position in global networks, while higher levels of segregation go together with a stronger position in global networks. The relation almost remains the same in terms of the strength (in fact it becomes slightly stronger) but was systematically at a higher level in 2011 compared to 2001. In short, there (still) is a firm relationship between globalisation and segregation.

[image:15.442.66.360.313.507.2]Next to the dimensions we referred to so far – social inequality and globali-sation – there are two context-sensitive dimensions that relate to the extent of welfare provision, indicating a type of welfare state, and the characteristics of

Figure 15.4 World city status and residential segregation between top and bottom social groups in selected European cities.

Notes: * Metropolitan region, **city.

Madrid, Tallinn, London, Budapest, Vilnius, Athens, Prague, Riga – managers and elementary occupations.

housing regimes. The forms of housing provision and the degree of housing com-modification are tightly linked to the type of welfare state, and both phenomena play a part in shaping levels of socio-economic and ethnic segregation (Arbaci 2007; Musterd and Ostendorf 1998). To further expose the contingent roots of the changing patterns of socio-economic segregation in Europe, we have adopted the well-known typology of welfare states proposed by Esping-Andersen (1990) along with its extensions to south Europe (Allen et al. 2004) and to the former socialist countries (Fenger 2007). Consequently, we distinguish between six types of European welfare regimes: democratic, corporatist, corporatist south European, corporatist post-socialist, liberal and liberal post-socialist. The former studies on ethnic divisions in Europe revealed that the liberal welfare-state correlates with evidently higher levels of segregation, while the corporatist and democratic welfare models are related to the lower scale of spatial disparities (Musterd and Ostendorf 1998).

With regard to housing regimes, an important element of the welfare state, we refer to Kemeny’s (2002) general division between unitary and dual housing regimes that reflects the degree of government’s direct (unitary) and indirect (dual) involvement in housing provision, regulations and subsidies. As this classification is somewhat crude, we are sensitive to regional variations of the two ideal types. Consequently, we also distinguish between the south European (Mediterranean) housing system (Allen et al. 2004) and the post-socialist variants of unitary and dual models. The Mediterranean and unitary housing regimes, especially when accompanied by different subtypes of the corporatist welfare-model, have been argued to result in lower levels of segregation than more market-oriented dual housing regimes (Arbaci 2007). It also seems that lower-income households in unitary regimes live in relatively better neighbourhoods compared with their counterparts in different forms of the dual regimes (Norris and Winston 2012). The results from the 13 European cities we included in this volume show that globalisation and post-Fordist economic restructuring contribute to the legible retrenchment of the welfare state in the new millennium (Figure 15.5).

374 Szymon Marcińczak et al.

than in the Netherlands. Institutional arrangements also differ between the coun-tries mentioned because of different economic structures and differences in terms of how projects have been financed, how mortgage systems have been developed and the like. This has had evident impacts as we see that a city like Stockholm has hardly been hit by the recent crisis, whereas Amsterdam and the Baltic States clearly have experienced rather strong effects. Also within southern Europe there are differences. What we see is that family solidarity networks (requiring spatial proximity) are still very important drivers for changing levels of segregation in Athens and Milan but gradually less so in Madrid. In East Europe, with the excep-tion of the Czech Republic that largely preserved the corporatist welfare regime and a significant public role in housing provision, the systemic transformation that started in the early 1990s brought about a massive privatisation of housing and a deep liberalisation and vanishing of social safety nets that, in turn, boosted the rising economic inequality.

[image:17.442.66.366.328.511.2]In Figure 15.5 the index of dissimilarity of the 12 cities is plotted against seven welfare-state and housing regimes. Overall, it seems that the different types of welfare-state and housing regimes are only modestly related to the levels of socio-economic spatial divisions of the top and bottom social strata in European cities, and that the relationship has weakened (Figure 15.5). However, there is more structure in the data than initially expected. In the early 2000s, former socialist cities, even those in the most liberal contexts, were still the least segregated.

Figure 15.5 Welfare states, housing regimes and residential segregation between top and bottom social groups in selected European cities.

Notes: * Metropolitan region, **city.

Madrid, Tallinn, London, Budapest, Vilnius, Athens, Prague, Riga – managers and elementary occupations.

This may be ascribed to the forced egalitarianism that existed under the totalitar-ian socialist regimes some decades ago. That impact changed from 1989/1991 onwards but only with a time lag. The differences between north-west and south Europe are also evident, with the dual housing regime and liberal welfare state being the most segregated and the social-democratic welfare regime characterised by noticeably lower levels of segregation. One relation is particularly intriguing, however. There are several welfare states that are rather similar, such as the demo-cratic welfare states in Norway and Sweden but perhaps also the Netherlands. Nevertheless, levels of segregation between the top and bottom of the social divi-sion are clearly different between the capital cities of these states (Oslo versus Amsterdam and Stockholm) or they develop in a different direction (Amsterdam versus Stockholm).

Levels of socio-economic segregation vary a lot within similar housing sys-tems. In some countries with strong public involvement in the housing sector (unitary housing system), we find both low levels of segregation (Prague) and high levels of segregation (Stockholm and Vienna). True, we do not know what would be the levels of socio-economic segregation in the latter two cities if no elaborate housing policies existed. In countries with dual housing systems, we find significant variation too. Tallinn and London represent high levels of seg-regation, while Oslo represents low levels of segregation. The latter implies that market-based housing systems should not necessarily lead to high levels of segre-gation, at least in the context of an otherwise generous welfare system.

Finally, various developments interfere with each other. Amsterdam, with its stronger position in terms of globalisation (which drives segregation up) also experienced more than a decade of more liberal housing market intervention (also driving segregation up), while after 2008 the crisis had its effects as well (freezing segregation patterns). In Sweden neo-liberalisation also has had its effect and cre-ated more social spatial inequality, with higher levels of separation between top and bottom social categories than before. In fact, both cities have moved into a direction which is comparable to what we see elsewhere in more easily recognised liberal contexts, such as London, but also in more recent liberal environments, such as Madrid and the capital cities of the Baltic States. In all cases we may observe a positive correlation between the liberal welfare and housing regimes and socio-economic segregation, but the relationship between welfare regimes and housing systems with residential segregation is very complex and requires more in-depth analysis.

Conclusions and new perspectives

376 Szymon Marcińczak et al.

changes in European capital cities and on the impact of globalisation, economic restructuring, welfare regime shifts and changing social inequality in general. We also referred to the previously developed historical development paths and to potential intervening factors, such as segregation in other domains, includ-ing ethnic/cultural and demographic domains. The introduction suggested that understanding social-spatial segregation in cities and/or their metropolitan areas is quite a challenge. Most importantly, the theory-grounded hypothesised ranking of European capital cities as introduced in Chapter 1 was not entirely confirmed by the actual patterns of socio-economic segregation. In this final section of the final chapter we will highlight some of the most salient findings from this volume and illuminate the mismatch between theory and reality.

We can draw two main conclusions from the analysis presented in this volume. The first is that the levels of socio-economic segregation in European capital cities are still rather modest. Segregation levels in cities in the Americas, Africa and parts of East Asia (Florida 2014; Maloutas and Fuijta 2012) are (much) higher than in Europe, and the negative side effects of high levels of segregation are only making their way into urban and political debates in Europe. However, the second main finding from this volume is that in the last decade Europe has been slipping, albeit slowly, into the epoch of growing inequalities and segregation. Under the influ-ence of (neo-)liberal transformations in welfare states, and under the influinflu-ence of the fact that several European cities also managed to become embedded in strong global networks and flows of people, the levels of socio-economic segregation are moving upwards. So far, this did not yet produce extreme levels of segregation in European cities, but Europe is clearly heading in the direction of higher levels of socio-economic divisions and especially in terms of the spatial separation of the top and bottom of social distributions. Three-quarters of the cities we included in this volume showed increasing levels of segregation of the top social categories, and a similar share showed increasing segregation of the lowest social categories. However, the spatial gap between the more extreme categories, those that have and those that have not, is widening in all capital cities across Europe.

as relatively short-term economic, financial or housing crises. These examples illustrate that for a fuller understanding of trends in socio-economic segrega-tion, we would need an extended time frame on top of the ten years we used in this volume to fully grasp the complex relation between inequality and segrega-tion. Finally, several contributions in this volume have discussed the relationship between socio-economic and ethnic segregation. In some places, neighbourhoods and cities, that relationship is strong, but it has also been shown that this is not a one-to-one relationship. In some cases social distances between social classes within the category non-natives were even bigger than social distances within the category natives. Caution is required here and researchers and policy makers should not automatically assume that ‘non-western’ migrants are all lower class.

Institutional arrangements – welfare-state regimes or housing regimes – may be developed in such a way that these can effectively temper social inequalities. However, welfare and housing regimes may also be designed in such a way that social inequalities are increased. We currently seem to have entered an era in which the latter type of regime has taken centre stage, with increasing segrega-tion as a result. Currently, even a country like Sweden, which has long been the example par excellence for redistributing affluence and therewith was the proto-type of a country that managed to avoid high levels of social spatial segregation, is showing rapidly increasing levels of segregation. Although there is no simple one-to-one relationship between the riots in Stockholm in the summer of 2013 and increasing socio-spatial segregation, the riots have caused much debate on the direction Sweden is taking and the causes of social unrest in the most deprived neighbourhoods (Malmberg et al. 2013). The actual European reality is that most welfare regimes have become more market oriented to stimulate the economy in a liberal way, with increasing social inequality as a side effect.

The relationship between increasing socio-economic segregation in Europe and situations that are seriously threatening urban social life (such as riots) is an issue that does not yet seem to be fully understood. Extreme forms of segregation include gated communities for the top end of the socio-economic distribution, and inaccessible ghettos or favelas for the bottom ends of the socio-economic distribution. The potential estrangement that may be the result of such contrasts – people increasingly will be unaware of the lives of contrasting classes – might be dynamite under the social stability of our future cities. The increasing number of no-go areas in our cities implies that ultimately major parts of cities are regarded to be no part of urban life anymore, which implies a serious limitation of free-dom in such cities, and are having a major impact on the lives of those living in these no-go areas. Social apartheid, a process involving social discrimination and manifested in very high inequalities and spatial separation of the rich and the poor (Löwy 2003), could be the ultimate outcome of these urban social processes.

378 Szymon Marcińczak et al.

result in more separated spatial divisions. But less market does not necessarily entail lower levels of segregation (see Oslo versus Stockholm). Globalisation seems to be a relatively strong indicator of segregation, as long as we are satisfied with the general conclusion that Alpha cities (cities which link major economic regions and states to the world economy) are more segregated than other types of cities. Yet other factors may enhance or mitigate such a relation. A further explanatory factor of socio-economic segregation to consider is ‘space’ and inherited urban physical fabric. Some areas retain their attraction for certain niche groups over a long period of time, although a new valuation of spaces also may occur. Inner-city neighbourhoods that were regarded as not being attractive in the 1970s and 1980s have been gentrified by middle-class households that settled in originally blue-collar neighbourhoods. On the other hand, some neighbourhoods, large estates of mass-produced blocks of flats in particular, have been steadily losing middle-class residents. Put differently, the social and physical upgrading of neighbourhoods, as well as the reverse trend of social and spatial decay of neighbourhoods, plays an important role in shaping new social geographies of segregation.

To conclude, we have found that levels of socio-spatial segregation in Europe are still relatively modest compared to the rest of the world, but that they are increasing. We found that four central indicators of the multi-factor approach – welfare and housing regime, globalisation and economic restructuring, rising social inequality and historical development paths – all play a big role in chang-ing the social urban landscape in Europe. It is also clear that understandchang-ing local institutional, social and physical contexts are crucial for a better understanding of changing social segregation patterns. These factors are, however, not stable over time, since contexts are changing continuously, through the enlargement of the European Union, neo-liberalization of states, immigration, economic crises and urban transformations. The ultimate lesson of this book is that a combination of both structural factors and a context-sensitive approach is needed to fully under-stand the socio-economic segregation processes to allow policy-makers to counter the negative effects that endanger the stability of European cities.

Acknowledgements

Notes

1 We use the term East Europe for countries that used to be part of the state-socialist centrally planned countries for the five decades after World War II (Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia and Lithuania in this book), and West Europe to the rest of Europe (Austria, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom in this book).

2 The shape of segregation curves in Athens might also be the result of the heterogeneous composition of occupations included in the group of ‘managers and higher representatives’. The group in Athens also includes middle and even low middle income categories.

References

Allen, J, Barlow, J, Leal, J, Maloutas,T and Padovani, L 2004, Housing and welfare in Southern Europe, Oxford, Blackwell Science.

Arbaci, S 2007, ‘Ethnic segregation, housing systems and welfare regimes in Europe’

International Journal of Housing Policy 7(4), 401–433.

Beaverstock, J, Smith, R and Taylor, P 2015, ‘Global city network’. Available online: http://www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc. Accessed 10 May 2015.

Booth, C 1887, ‘The inhabitants of Tower Hamlets (School Board Division), their condition and occupations’, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 50(2), 326–401.

Booth, C 1888, ‘Conditions and occupations of the people in East London and Hackney’

Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 51(2), 276–331.

Butler, T, Hamnett, C and Ramsed M 2008, ‘Inward and upward: Marking out social class change in London, 1981–2001’ Urban Studies 45(1), 67–88.

Brown, L A and Chung, C Y 2008, ‘Market-led pluralism: Rethinking our understanding of racial/ethnic spatial patterning in U.S. cities’ Annals of the Association of American Geographers 98(1), 180–212.

Burgers, J and Musterd, S 2002, ‘Understanding urban inequality: A model based on existing theories and an empirical illustration’ International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 26(2), 403–413.

Castells, M 1989, The informational city, Oxford, Blackwell.

Dangschat, J 1987 ‘Sociospatial disparities in a “socialist” city: the case of Warsaw at the end of the 1970s’ International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 11(1), 37–60.

Duncan, O D and Duncan, B 1955, ‘Residential distribution and occupational stratification’

American Journal of Sociology 60(4), 493–503.

Engels, F 1892, The condition of the working class in England in 1844 London, David Price. Esping-Andersen, G 1990, The three worlds of welfare capitalism, Cambridge, Polity. Fainstein, S S, Gordon, I and Harloe, M 1992, Divided cities: New York and London in the

contemporary world, Oxford, Blackwell.

Farley, R, Schuman, H, Bianchi, S, Colasanto, D and Hatchet, S. 1978, ‘Chocolate city, vanilla suburbs: Will the trend toward racially separate communities continue?’ Social Science Research 7(3), 319–344.

Fenger, H 2007, Welfare regimes in Central and Eastern Europe: Incorporating post-communist countries in a welfare regime typology. Available online: http://journal.ciiss. net/index.php/ciiss/article/viewPDFInterstitial/45/37. Accessed 10 May 2015.

Fischer, C S, Stockmayer, G, Stiles, J and Hout, M 2004, ‘Distinguishing the geographical levels and social dimensions of U.S. metropolitan segregation 1960–2000’ Demography

380 Szymon Marcińczak et al.

Florida, R 2014, ‘The U.S. cities with the highest levels of income segregation’. Available online: http://www.citylab.com/work/2014/03/us-cities-highest-levels-income-segregation/ 8632/. Accessed 28 April 2015.

Freeman, L 2009, ‘Neighborhood diversity, metropolitan segregation and gentrification: What are the links in the US?’ Urban Studies 26(10), 2079–2101.

French, R A and Hamilton F E I (eds) 1979, The Socialist city: Spatial structure and urban policy, New York, John Wiley & Sons.

Fujita, K 2012, ‘Conclusions: Residential segregation and urban theory’ in Residential segregation around the world: Why context matters, eds. T Maloutas and K Fujita, London, Ashgate, pp. 285–315.

Galster, G and Booza J 2007, ‘The rise of bipolar neighborhood’ Journal of the American Planning Association 73(4), 421–435.

Hamnett, C 1994, ‘Social polarisation in global cities: Theory and evidence’ Urban Studies

31(3), 401–424.

Hamnett, C 2012, ‘Urban social polarization’ in International handbook of globalization and world cities, eds B Derudder, M Hoyler, P J Taylor and F Witlox, Cheltenham, UK, Edward Elgar, pp. 361–368.

Huttman, E, Blauw, W and Saltman, J (eds) 1991, Urban housing: Segregation of minori-ties in Western Europe and the United States, Durham, NC, Duke University Press. Kantor, P and Savitch, H V 2005, ‘How to study comparative urban development politics:

A research note’ International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 29(1), 135–151. Kemeny, J 2002, From public to the social market:Rental policy strategies in comparative

perspective, London, Routledge.

Kovács, Z, Wiessner, R and Zischner, R 2013, ‘Urban renewal in the inner city of Budapest: Gentrification from a post-socialist perspective’ Urban Studies 50(1), 22–38. Ladányi, J 1989, ‘Changing patterns of residential segregation in Budapest’ International

Journal of Urban & Regional Research 13(4), 555–572.

Lowy, M 2003, ‘The long march of Brazil’s labor party. Brazil: A country marked by social apartheid’ Logos 2(2). Available online: http://www.logosjournal.com/lowy.htm. Accessed 28 April 2015.

Malheiros, J 2002, ‘Ethni-cities: Residential patterns in the northern European and Mediterranean metropolises – implications for policy design’ International Journal of Population Geography 8(1), 107–134.

Malmberg, B Andresson, E and Östh J 2013, ‘Segregation and urban unrest in Sweden

Urban Geography, 34(7), 1031–1046.

Maloutas, T 2007, ‘Segregation, social polarization and immigration in Athens during the 1990s: Theoretical expectations and contextual difference’ International Journal of Urban and Regional Studies 31(4), 733–758.

Maloutas, T and Fujita, K (eds) 2012, Residential segregation in comparative perspective. Making sense of contextual diversity. City and society series, Farnham, UK, Ashgate. Manley, D and Johnston, R 2015, ‘London: A dividing city, 2001–11?’ City 18(6), 633–643. Manley, D and van Ham, M 2011, ‘Choice-based letting, ethnicity and segregation in

England’ Urban Studies 48(14), 3125–3143.

Marcińczak, S, Gentile, M, Rufat, S and Chelcea, L 2014, ‘Urban geographies of hesitant transition: Tracing socio-economic segregation in post-Ceausescu Bucharest’

International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38(4), 1399–1417.

Marcińczak, S,Tammaru, T, Novak, J, Gentile, M, Kovács, Z, Temelova, J,Valatka, V, Kährik, A and Szabo, B 2015, ‘Patterns of socioeconomic segregation in the capital cities of fast-track reforming postsocialist countries Annals of the American Association of Geographers 105(1), 183–202.

Marcuse, P. 1989, ‘“Dual city”: A muddy metaphor for a quartered city’ International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 13(4), 697–708.

Marcuse, P and van Kempen, R (eds) 2002, Of states and cities: The partitioning of urban space, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Massey, D S 1996, ‘The age of extremes: Concentrated affluence and poverty in the twenty-first century’ Demography 33(4), 395–412.

McFarlane, C and Robinson, J 2012, Introduction – experiments in comparative urbanism

Urban Geography 33(6), 765–773.

Morgan, B 1975, ‘The segregation of socio-economic groups in urban areas: A comparative analysis’ Urban Studies 12(1), 47–60.

Morgan, B 1980, ‘Occupational segregation in metropolitan areas in the United States, 1970’ Urban Studies 17(1), 63–69.

Musterd, S 2005, ‘Social and ethnic segregation in Europe; Levels, causes and effects’

Journal of Urban Affairs 27(3), 331–348.

Musterd, S and Ostendorf, W (eds) 1998, ‘Urban segregation and the welfare state: Inequality and exclusion in Western Cities, London, Routledge.

Musterd, S, van Gent, W, Das, M and Latten, J 2014, ‘Adaptive behaviour in urban space; Residential mobility in response to social distance’ Urban Studies DOI: 10.1177/0042098014562344. Accessed 28 April 2015.

Musterd, S and van Kempen, R 2007, ‘Trapped or on the springboard? Housing careers in large housing estates in European cities’ Journal of Urban Affairs 29(3), 311–329. Nightingale, CH 2012, Segregation: A global history of divided city, Chicago, University

of Chicago Press.

Nijman, J 2007, ‘Introduction – comparative urbanism’ Urban Geography 28(1), 1–6. Norris, M and Winston, N 2012, ‘Home-ownership, housing regimes and income inequalities

in Western Europe’ International Journal of Social Welfare 21(2), 127–138.

Park, E P, Burgess, E W and McKenzie, R D 1925. The city: Suggestions for investigation of human behavior in the urban environment, Chicago, University of Chicago Press. Pickvance, C1986, ‘Comparative urban analysis and assumptions in comparative research’

International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 10(2), 162–184.

Piketty, T 2013, Capital in the 21st century, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press. Préteceille, E 2000, ‘Segregation, class and politics in large cities’ in Cities in contemporary

Europe, eds A Bagnasco and P Le Gales, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 74–97. Reardon, S F and Bischoff, K 2011, ‘Income inequality and income segregation’ American

Journal of Sociology 116(4), 1092–1153.

Robinson, J 2011, Cities in a world of cities: The comparative gesture’ International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35(1), 1–23.

Sassen, S. 1991, The global city: New York, London, Tokyo, Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press.

Smith, N 2002, ‘New globalism, new urbanism: Gentrification as global urban strategy’

Antipode 34(3), 427–450.

Stanilov, K and Sýkora, L (eds) 2014, Confronting suburbanization: Urban decentraliza-tion in postsocialist Central and Eastern Europe, Oxford, Wiley Blackwell.

382 Szymon Marcińczak et al.

Sýkora, L 2009, ‘New socio-spatial formations: Places of residential segregation and separation in Czechia’ Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 100(4), 417–435.

Szelényi, I 1987, ‘Housing inequalities and occupational segregation in state socialist cities. Commentary to the special issue of IJURR on east European cities’ Interna tional Journal of Urban and Regional Research 11(1), 1–8.

Tammaru, T and Kontuly, T 2011, ‘Selectivity and destinations of ethnic minorities leaving the main gateway cities of Estonia’ Population, Space and Place 17(5), 674–688. Tammaru, T, Kährik, A, Mägi, K Novák, J and Leetmaa, K 2016a, ‘The “market

experi-ment”: Increasing socio-economic segregation in the inherited bi-ethnic context of Tallinn’ in Socio-economic segregation in European capital cities: East meets West, eds T Tammaru, S Marcińczak, M van Ham and S Musterd, London, Routledge.

Tammaru, T, Musterd, S, van Ham, M and Marcińczak, S, 2016b, ‘A multi-factor approach to understanding socio-economic segregation in European capital cities’ in Socio-economic segregation in European capital cities: East meets West, eds T Tammaru, S Marcińczak, M van Ham and S Musterd, London, Routledge.

van Ham, M and Manley, D 2009, ‘Social housing allocation, choice and neighbourhood ethnic mix in England’ Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 24, 407–422. van Kempen, R 2007, ‘Divided cities in the 21st century: Challenging the importance of

globalization’ Journal of Housing and Built Environment 22(1), 13–31.

van Kempen R and Murie, A 2009, ‘The new divided city: Changing patterns in European cities’ Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 100(4), 377–398.

Villaca, F 2011, ‘São Paulo: urban segregation and inequality’ Estudos Avançadosvol

25(71), 37–58

Ward, K 2010, ‘Towards a relational comparative approach to the study of cities’ Progress in Human Geography 34(4), 471–487.

Watson, T 2009, ‘Inequality and the measurement of residential segregation by income in American neighborhoods’ The Review of Income and Wealth 55(3), 820–844.

York, A M, Smith, M E Stanley, B W, Stark, B L, Novic, J, Harlan, S L, Cowgill, G L and Boon, CG 2012, ‘Ethnic and class clustering through the ages: A transdiciplinary approach to urban neighbourhood social patterns’ Urban Studies 48(11), 2399–2415. Zorbaugh, HW 1929, The gold coast and the slum: A sociological study of Chicago’s near