i

CORRELATES OF CRIMINAL RECIDIVISM IN MAXIMUM

PRISON FACILITIES IN KENYA

BY

GRACE ANYANGO J (M.A. Sociology)

C82/20469/2010

A Thesis Submitted in Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) to the School of Humanities and Social Science of Kenyatta University.

DECLARATION

This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other university or any other award.

Signature Date……….

GRACE ANYANGO J. (M.A. Sociology) REG. NO C82/20469/2010

Department of Sociology Kenyatta University

Supervisors

We confirm that the work reported in this thesis was carried out by the student under our supervision.

Signature_______________________________Date:___________________ DANIEL MUIA (Ph.D.)

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY KENYATTA UNIVERSITY

Signature______________________________ Date.___________________ WILSON A.P OTENGAH (Ph.D)

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY

DEDICATION

This work is dedicated to my dear husband Tobias and our lovely children Mark and Winnie. To my husband who saw the misgivings I had to commence the doctoral program but calmly assured me of my potential to make it. To Mark who sacrificed his free time to be Mum‘s driver, photographer and research assistant, many were the times when I got bogged down in the field but his enthusiasm gave me the courage to carry on. To Winnie who never shied from saying how I have raised the education bar but promised to follow Mums footsteps. To my late parents: Mom and Dad, I miss you. I‘m forever grateful for your struggles to bring up a family of eight and for instilling in me great values.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I acknowledge the contributions of my supervisors Dr. Daniel Muia and Dr. Wilson A.P. Otengah. Your professional and dedicated teaching and guidance throughout this exercise is invaluable. I also thank the chairperson, department of sociology Dr. Ombaka for his input and guidance. Dr. Lucy Maina and Dr George Owino for the insights that greatly shaped my work; Dr Samwuel Mwangi, Mr.Lawrence Alaro, Dr. Moloo, Dr. Otiato and Dr. Nyachio whose expertise and immense contributions shaped the outcome of the thesis. I am indebted to Sociology department, Kenyatta University for the friendly learning environment.

I owe special thanks to the following: the Commissioner General of Prisons, Mr. Isaiah Osugo, for his input and authorizing unrestricted access to the Prison facilities; Madam Wanini, Mr Ogore and Officers-In-charge of Kamiti and Langata Prisons, for their coordination which made my data collection a success; the Director Probation Mr. Oloo, CSO Coordinator, Mr. Etiang, Director Rehabilitation Mrs. Khaemba and PPO, Nairobi area Mr. Matagaro whose expertise shaped this work.

Central Sector and office colleagues for all the support. To the Christian community in Zalingei, Central Darfur thanks so much for the prayers.

I am greatly indebted to all the inmates from Kamiti and Langata Maximum prisons who participated so willingly in the data collection. I wish to thank many people who contributed to the success of this thesis but I have not been able to mention their names.

Last but not least, I wish to acknowledge with love, the patience and all assistance accorded to me by my husband and children during this study. Thanks so much for being my rock in the storm of academic world. You gave me a solid elevated surface to stand on when the water rose above my shoulders and I felt as though I was drowning. My deepest gratitude goes to the Almighty God to whom, thanks are never sufficient.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DECLARATION ... i

DEDICATION ... iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ... iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... vi

LIST OF TABLES ... xii

LIST OF FIGURES ... xv

LIST OF PLATES ... xvi

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMNS ... xvii

ABSTRACT ... xviii

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1 Background to the Study ... 1

1.2 Statement of the Problem. ... 8

1.3 Purpose of the Study ... 10

1.4 The Objectives of the Study ... 10

1.5 Study Hypothesis ... 10

1.6 Justification and Significance of the Study ... 11

1.7 Scope and Limitations of the Study ... 13

1.8 Organization of the thesis... 14

1.9 Operational definition of terms ... 14

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORITICAL FRAMEWORK ... 18

2.1 Introduction ... 18

2.2 Correctional System Factors Influencing Offender Relapse ... 18

2.3 Individual Factors of an Offender ... 31

2.4 Community Factors Affecting Criminal Recidivism ... 36

2.6 Theoretical Framework ... 46

2.6.1 Social Control Theory ... 46

2.6.2 Labeling Theory ... 49

2.6.3 Social Learning Theory ... 51

2.6.4 Routine activity theory ... 54

2.6.5 Bronfenbrenner‘s Ecological Theory ... 55

2.7 Conceptual Framework ... 57

CHAPTER THREE: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY ... 59

3.1 Introduction ... 59

3.2 Research Design ... 59

3.3 Site of study ... 60

3.4 Study Population ... 60

3.5 Unit of Analysis ... 61

3.6 Sampling Techniques and sample size ... 61

3.6.1 Inclusion Criteria ... 63

3.6.2 Exclusion Criteria... 63

3.7 Sampling Size Distribution ... 63

3.7.1 Research Instruments ... 64

3.7.2 Questionnaire ... 64

3.7.3 Interview Schedule ... 65

3.7.4 Focus Group Guides ... 65

3.8 Sources of Data ... 65

3.9 Data Collection Procedure ... 65

3.10 Instrument Validity and Reliability ... 66

3.11 Data management and processing ... 66

3.12 Data Analysis ... 67

3.13 Data Presentation Techniques ... 67

CHAPTER FOUR: DATA ANALYSIS, PRESENTATION AND

INTERPRETATION ... 69

4.1 Introduction ... 69

4.2 Socio-demographic Characteristics of Respondents. ... 70

4.2.1 Socio- demographic variables of the respondents ... 71

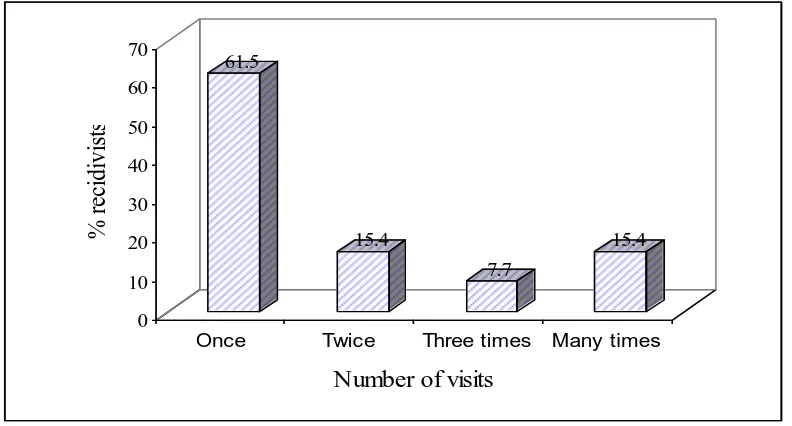

4.3 Correctional system factors influencing offender relapse ... 72

4.3.1 Contact with outside world ... 73

4.3.1.1 Letter writing ... 74

4.3.1.2 Prison visitation and social support... 75

4.3.1.2.1 Regularity of the visit ... 78

4.3.1.2.2 Visit Durations ... 79

4.4 Transition Programming ... 81

4.4.1 Prison programming and transition services ... 85

4.4.2 Reentry Challenges ... 87

4.4.3 Challenges with family on discharge ... 90

4.4.4 Inmates‘ perspective on drivers to reoffend ... 91

4.4.5 Sustaining rehabilitation efforts on the outside ... 93

4.5. Classification system ... 94

4.6 Discharge preparation ... 96

4.6.1 Specific Program participation and preparedness at discharge ... 99

4.7 Program effectiveness ... 100

4.7.1 Relevance of skills on discharge ... 101

4.7.2 Programming and criminal relapse ... 103

4.7.3 Women respondents and programming ... 105

4.7.4 Effectiveness of prison programming in addressing criminogenic factors ... 108

4.7.5 Programming in relation to offence committed ... 120

4.7.6 Re-offence crime and correctional program success ... 122

4.7.7 Imprisonment and Recidivism ... 127

4.8 Program Placements in current and previous convictions ... 131

4.8.1 Programme placement by gender ... 136

4.8.3 Programming and Risk Levels ... 143

4.9 Hypothesis one ... 144

4.9.1 Establishing Risk levels of Program participant and Non participants ... 148

4.10. Hypothesis two ... 149

4.10.1 Risk Assessment and prisoner‘s program placement ... 152

4.10.2 Number of previous convictions and program placement ... 154

4.10.3 Prison Environment and programming ... 155

4.10.3.1 Positive aspects of prison environment ... 157

4.10.3.2 Negative aspects of prison environment ... 158

4.11 Summary of correctional factors ... 161

4.12 Individual Factor on Criminal relapse of offenders ... 164

4.13 Impulsivity ... 165

4.13.1 Amount of planning before crime commission ... 165

4.13.2 Impulsive behavior ... 167

4.13.3 Ability to defer immediate rewards... 168

4.13.4 Anger and Impulsivity... 171

4.14 Education... 172

4.14.1 Educational level of the respondents on reconviction ... 172

4.15 Job skills ... 176

4.16 Anti-social attitudes ... 177

4.16.1 Attitude towards police in the community ... 180

4.17 Alcohol Use and Drug abuse ... 181

4.17.1 Effect of alcohol use in crime commission ... 181

4.18 Influence of Alcohol on criminal relapse ... 183

4.18.1 Alcohol use 6 months before imprisonment ... 185

4.18.2 Drug use a month before current incarceration ... 185

4.18.3 Use of more than one drug ... 186

4.19 Criminal associates... 188

4.19.1 Respondents perspectives to causes of Criminal relapse... 191

4.20 Summary of Individual factors... 195

4.22 Support services in the community during discharge ... 198

4.22.1 Source of support in the community... 202

4.22.2 Family/friends support ... 202

4.23. Community supervision ... 208

4.24. Reception at discharge ... 211

4.24.1 Immediate problems during last discharge ... 212

4.24.2 Community Reception ... 214

4.25 Employment of ex-offenders ... 215

4.25.1 Securing employment after discharge ... 216

4.25.2 Retaining Employment on discharge ... 218

4.26 Housing upon discharge ... 221

4.26.1 Difficulties in searching housing by Gender ... 223

4.26.2 Moving housing ... 224

4.27 Discrimination in community ... 226

4.28 Summary of community factors Community factors ... 228

4.29 Combined Model ... 231

CHAPTER FIVE: SUMMARY OF ANALYSIS, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ... 235

5.1 Introduction ... 235

5.2 Summary of findings ... 235

5.2.1 Correctional System factors influencing offender relapse ... 236

5.2.2 Individual factors contributing to criminal relapse of offenders ... 239

5.2.3 Community factors influencing offender relapse ... 240

5.3 Conclusions ... 241

5.4 Recommendations ... 244

5.4.1 General recommendations ... 244

5.4.2 Policy Recommendations ... 246

REFERENCES ... 251

APPENDICES ... 266

Appendix 1: Case Study of Ex- Offender In The Community... 266

Appendix 2: Reseach Instrument: Questionnaire ... 267

Appendix 3: Focus Group Discussion Guide ... 284

Appendix 4: Key Informat Interview Guide ... 286

Appendix 5: Informed Consent ... 289

Appendix 6: Table For Determining The Needed Sample Size ... 291

Appendix 7: Research Photos ... 292

Appendix 8: Research Authorization ... 294

Appendix 9: Research Permit... 295

LIST OF TABLES

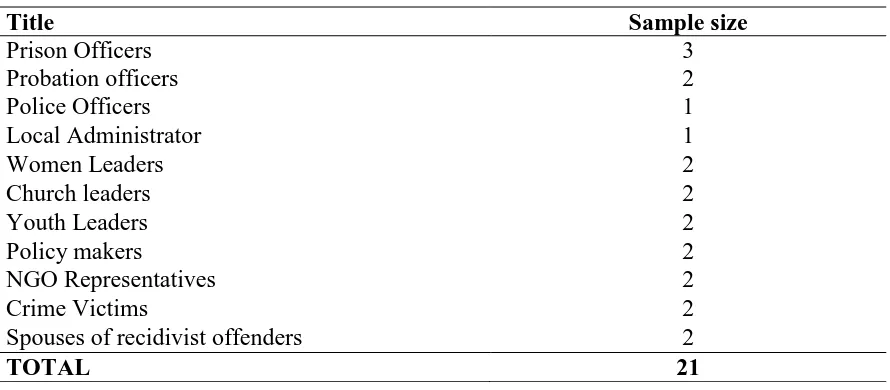

Table 3.1: Sampling size distribution of main Respondents ... 63

Table 3.2: Sample Size Distribution of Key Informants ... 64

Table 4.1: Response rate for the study ... 69

Table 4.2: Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents ... 70

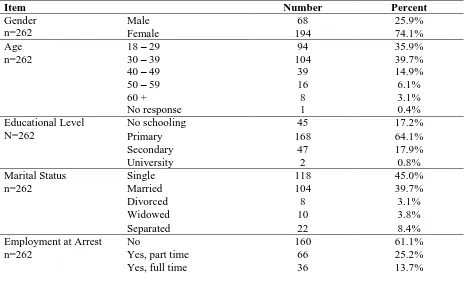

Table 4.3: Correctional factors associated with criminal relapse ... 73

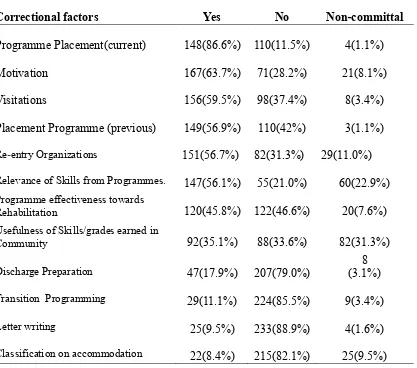

Table 4.4: Relationship with the persons who visited the recidivists in prison ... 79

Table 4.5: Visitors duration... 80

Table 4.6: Programs the recidivist felt was best geared towards preparing them for community re-entry ... 86

Table 4.7: Respondents ratings on impediments on safe reentry ... 87

Table 4.8: Challenges with family members... 90

Table: 4.9: Inmates perspective on drivers to reoffend ... 91

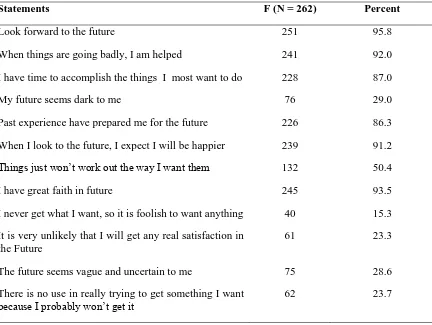

Table 4.10: Beck‘s Hopelessness scale and respondents views ... 92

Table 4.11: Sustaining rehabilitation program on the outside ... 93

Table 4.12: Programming and level of preparedness at discharge by Gender ... 96

Table 4.13: Chi-Square Tests result for the number of times recidivists had been to prison by gender ... 97

Table 4.14: Level of preparedness during previous conviction at discharge ... 97

Table 4.15: Specific programs participation and level of preparedness of respondents during last discharge ... 100

Table: 4.16: Usefulness of skills acquired in previous conviction... 101

Table 4.17: Usefulness of previous programming by gender ... 103

Table: 4.18: Prison programming and re-offending ... 104

Table 4.19: Cross tabulation on Number of convictions and program placements ... 109

Table 4.20: Cross tabulation of Recidivists who had problem of alcohol abuse by programs ... 113

Table 4.21: Levels of alcohol effect and programming ... 114

Table: 4.22: Movement from one program to another ... 118

Table: 4.24: Crimes committed first, second and third time conviction ... 127

Table 4.25: Inmates perspective to possibility of engaging in crime in the future ... 128

Table 4.26: Mean length of imprisonment of the recidivist on the first, second, third and fourth imprisonment ... 129

Table 4.27: Engagement in prison programming ... 131

Table: 4:28: Specific Programme placements in current and previous convictions ... 133

Table 4.29: Programming by gender in current sentence ... 136

Table 4.30: A cross tabulation of program placement by gender during previous conviction ... 137

Table 4.31 A cross tabulation of Specific Programme engagement by gender ... 137

Table 4.32: Recidivists feelings in the programs they were involved in the prison ... 139

Table 4.33: Programs the recidivists would like to engage in given opportunity ... 142

Table 4.34: Levels of risks of Respondents ... 143

Table 4.35: Risk level by Gender ... 143

Table 4:36: Risk level by Programme placement ... 144

Table 4.37: Program placement and Respondents Risk Levels ... 145

Table 4.38: Program placement and risk level ... 147

Table 4.39: T-test for risk scores for recidivists placed and not placed programmes .... 149

Table 4.40: Cross tabulation of program placement in first and second convictions .... 152

Table 4.41a: Correlation table for number of times in prison and program placement . 154 Table 4.41b: Correlation table for number of times in prison and current programme placement ... 155

Table 4.42: Difficulties faced by the recidivists as a result of their imprisonment ... 156

Table 4.43: Positive influences of imprisonment ... 157

Table 4.44: Negative influences of imprisonment ... 158

Table 4.45: Correctional system predictors of criminal relapse by recidivist offenders 162 Table 4.46: Individual factors ... 164

Table 4.47: Time taken to commit crime ... 166

Table 4.48: Reasons for not thinking through ... 168

Table 4.49 (a): Impulsivity and criminal relapse ... 169

Table 4.51: Level of education... 173

Table 4.52: Reasons for dropping out of schools ... 175

Table 4.53: Type of employment the recidivist were engaged in ... 176

Table: 4.54: Recidivist monthly incomes at the time of employment ... 177

Table 4.56: Reasons for regret ... 179

Table 4.57: Recidivists attitude towards the police ... 180

Table 4.58: Cut, Annoyed, Guilty, Eye opener questioner responses (CAGE) ... 182

Table 4.59: Level of alcohol effects ... 183

Table 4.60: Chi-square table for risk level by alcohol abuse problem... 184

Table 4.61: Alcohol use 6 months before imprisonment- frequency of alcohol intake . 185 Table 4.62: Drug Used 6 months before imprisonment ... 186

Table 4.63: Use of more than one illegal substance - same Day Cross tabulation ... 187

Table 4.64: Respondents in a group at the time the crime was committed ... 189

Table 4.65: Factors influencing recidivist‘s behavior leading to imprisonment ... 191

Table 4.66: Strategies to avoid recidivism ... 192

Table 4.67: Individual factor predictors of criminal relapse by recidivist offenders ... 196

Table 4.68: Community Factors ... 198

Table 4.69: The persons whom respondents count on ... 204

Table: 4.71: Persons who received the recidivists at the gate of the prison on discharge211 Table 4.72: Immediate problems faced by recidivists on discharge ... 212

Table 4.74: Persons with whom the recidivists stayed with during last discharge ... 222

Table 4.75: A cross tabulation on Problem in searching housing by Gender ... 223

Table 4.76: Moved or retained previous residence during last discharge- Gender cross tabulation ... 224

Table 4.77: Recidivists‘ reasons for moving from the previous residence ... 225

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 2.1: Conceptual Framework... 58

Figure 4.1: Number of visits received by the recidivists the previous year ... 78

Figure 4.2: Average Jail terms for first and second offences ... 122

Figure 4.3: Reasons for not securing a job during last discharge ... 173

Figure 4.4: Association with criminal others at the time of crime ... 189

Figure 4.5: Support in the community ... 202

LIST OF PLATES

Plate 1: Unresolved Trauma and Programming of women offenders ... 107

Plate 2 & 3 Nature of specific crimes committed by recidivists‘ offenders ... 121

Plate 4: Violent offences leaving families in shock ... 126

Plate 5: Very young recidivists‘ offenders involved in high profile crimes ... 126

Plate 6: Newly released prisoner steal church offering two days after discharge. ... 130

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMNS

ART: Article

BJS: Bureau of Justice Statistics DAT: Differential Association Theory GLM: Good Lives Model

ICCPR: International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights ICPS International Center for Prison Studies

KPS: Kenya Prisons Service MI: Motivational Interviewing

MPRI: Michigan Prisoner Re-entry initiative

OARS: Open questions, Affirmations, Reflections and Summaries NGO: Non-Governmental Organization

PREP: Post Release Employment Program RNRM: Risk Need and Responsivity Model SMR: Standard Minimum Rules

ABSTRACT

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background to the Study

A major issue in the criminal justice policy is the differential effectiveness of sentences, programs, and/or their interventions in achieving criminal justice goals. The search for systematic means of enhancing effectiveness is invariably the issue of addressing recidivism. There has been an increase in the population of incarcerated adult offenders that has largely been contributed to by repeat offender crime. This has impacted negatively on public safety policies in countries globally. High crime rates threaten the safety of communities and at times evoke responses which, according to Albertus, (2010), erode the aspiration to live in a state founded on human dignity, freedom and equality. From public safety perspective, a lot of time and resources is invested within the criminal justice chain, only for the offenders to recidivate in the long run. This has contributed to the high rates of crime throughout the world calling for different strategies and methods in trying to control it.

Effective rehabilitation and reintegration of offenders has proven to be a challenge in many jurisdictions calling into question the handling of offenders within the criminal justice system. As brought out by Sarkin (2009) effective and supported rehabilitation programmes should be able to reduce recidivism. This is premised on the fact that programme participation improves the functioning of individual offenders by addressing deficiencies thereby decreasing the likelihood of rearrests, reconviction and incarceration (Davis 2013). Empirical evidence provides that several risk factors increase the likelihood that ex-offenders will reoffend and return to prison on new charges. Risk factors include; antisocial behavior, negative peer influence, Impulsivity, socio economic status, criminal history and length of prior sentence (Wikoff et al 2013). Majority of incarcerated offenders have limited education, job skills, vocational training and employment (Alexander, 2012). In addition, some suffer addiction, strained family relationships and large numbers coming from impoverished communities (Brohomme et al 2016). They in turn serve long prison sentences (Jung 2011) and are constrained with availability of programming space (Hall 2015) arising from limited budget ceilings (Cheyet & Brown 2010). This is coupled with limited support and fewer family relationships, contacts and visits while incarcerated (Bales & mears, 2008, Duwe 2012). They also face barriers arising from lack of prerelease preparation. On discharge, they struggle to find stability (Bell, 2014).

highest recidivism rate in the world at 90 per cent, followed with Germany and Asia at 74 per cent. The Netherlands tops the world with the least number of criminals, Switzerland ranks second with a 22 per cent recidivism rate followed by Norway at 30 per cent. In Africa, South Africa has 74 per cent, Kenya 47 per cent, Rwanda and Tanzania 36 per cent and Zambia 33 per cent recidivism rates respectively. Uganda records lowest recidivism rate in East Africa (Wambugu, 2007). Such high rates of recidivism apparent in number of countries, referred to as revolving door, has captured attention of both researchers and policy makers alike. High rates of recidivism are costly in various ways including public safety, increased government budget to arrest, prosecute and probably re incarcerate repeat offenders (McKean, 2004). It also exacerbates the problem of the rapid growth of prison population and correctional spending (Clear, 2010). This not to mention other collateral and social costs of imprisonment including healthcare, unemployment and other welfare supports, social isolation and family support.

A critical issue that has emerged is what to do with serious offenders once their prison terms are served. Some believe that the risk posed to the community by the possibility of these offenders reoffending is sufficient to warrant their continued detention. As they exit prison custody, many individuals leave with expectation of leading productive and law abiding lives. They however, experience frustrations as they are unable to meet their expectations on reentering the community. Often times, they return to their respective communities poorly educated, with substance abuse and mental health concerns. Majority lack a positive support system and they do not have access to housing or cash. Along with the barriers, many are faced with stigma of a criminal record as they seek employment. In most cases, ex-offenders face various barriers with limited access to resources (Gottchall & Amour, 2011). Moreover, recidivism statistics suggests that, for a majority, prison experiences fail to have any deterrent or rehabilitative effect in preventing future offending as the case of Australian prisons with over half (55%) of its population having previously served a sentence (ABC, 2011). Despite long periods of incarceration as the case of inmates in maximum level facilities, most do not have proper preparation to transition into community and abide by the rules and regulations on the outside (Richards and Jones, 2004).

to Angote (1981), when prisoners are released from prison custody, they are not fully accepted on return. Also, given that many offenders who were removed from communities committed serious violent crimes, it is not immediately obvious that communities would be ready to accept offenders re-entering their community space. Opinions about appropriate policy responses to prisoner reentry vary widely. Some suggestions include community involvement in supervising ex-prisoners, (Petersilia, 2000) or development of reentry courts as a mechanism for managing the transition back into the community (Travis, 2000).

Correctional systems in Africa share recidivism burden as the case with many countries worldwide. Some of the challenges maybe spill over from its history taking into account that prison system is not an indigenous African institution but a handover from the colonial power. Historically, the penal system was meant by the Europeans to isolate and punish political opponents, entrench racial superiority and administer capital and corporal punishment. Africa‘s earliest experience with formal prisons was hence not targeted toward rehabilitation or reintegration of criminals but rather economic, political and social subjugation of indigenous people (Pete, 1986). Before introduction of the penal system to Africa and indeed Kenya, traditional African societies had means of social control, reformation and moral cleansing which served then as instruments for providing justice. This included the elders of councils, chiefs, village heads, etc., whose function was the interpretation of the code of conduct and behaviour of the subsisting community as passed down from generations to generation. It is a fact that traditional societies did not have written laws to guide conduct as observed in and by the western societies, but it had well-established institutions for controlling crime and maintaining social order (Akintola, 1982).

Traditional crime control in Nigerian communities had its roots in kinship and extended family system. In Kenya, many communities confronted delinquent acts through the authority of councils of elders that had powers to levy fines, demand community service, administer corporal punishment, or ostracize altogether. The Meru tribe, for example, has a council of elders known

as Njuri Ncheke, whose functions are ―to make and execute tribal laws, to listen to and settle

Kambi, maintained order and determined guilt in difficult situations (Brantley, 1978).). Many other large tribes such as the Kikuyu, the Kalenjin, the Maasai and the Kamba had varied community-based mechanisms of social control in ways that were consistent with their traditional belief systems.

Religion and in particular, Africa traditional one, was also regarded as one best way in controlling crime in the African society. Durkheim (1961) viewed religion as unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community. In Africa traditional societies, religious ties created propitious leverage for strong community ties and less crime, (Ayuk, 2012). The coming of the Europeans changed the people‘s cognitive mapping of what constitutes social order and control through the introduction of new methods leading to the abandonment of the traditional social control patterns, systems and mechanisms. Over the years, rehabilitation in Africa is part of many regional instruments aimed at improving prison conditions throughout the continent. The 2000 Ouagadougou Declaration, (Penal Reform International, African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights, 2000), on accelerating prison and penal reform in Africa called for the promotion of rehabilitation and reintegration of former offenders. The declaration also specifies measures the governments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) could take to increase effectiveness of rehabilitation of offenders in the continent.

and three body guards within Nairobi‘s central business district, and an attempt by a newly discharged inmate to steal church offerings during a church service in Lakipia West two days after discharge on presidential amnesty are some of the many offences reported by Kenyan print and electronic media in the recent past to have been committed by people said to be ex-offenders . The continued relapse into crime by ex-ex-offenders has resulted in Kenya having one of the highest rates of prison overcrowding globally as reported by Penal Reform International in a 2010 world report. Data from Kenya Prisons Service (KPS) for the same period indicate that a total of 88,531 convicted and 165,739 non convicted prisoners were admitted in various prisons in the country. Out of 88,531 convicted admissions, 29,652 were repeat offenders accounting for 33.5 per cent. In direct correlation with this high level of incarceration, the country also discharges some 255,000 (convicted and non-convicted) inmates back to various communities across the country annually. This trend suggests that criminals are not desisting from crime and yet government resources are continually invested in trying to reform them. Based on the above, this study investigated correctional, individual and community correlates of criminal recidivism in Kenya.

1.2 Statement of the Problem.

exposure to criminogenic tendencies for the inmates and simply confine and cut them from their societal attachment, where they are stigmatized based on their new status as ex- offenders.

The reoffenders, without doubt, contribute to the enormous growth of the prisons‘ population, allocated resources and increased crime rates. The resources are used in addressing the additional crime committed by reoffenders; from arrest, prosecution, to further rehabilitation and re-entry back to community. This definitely has tremendous negative socio-economic effects on overall social security and economy. These resources would otherwise be used to gainfully address individual, correctional and community factors that lead to re-incarceration. Also, despite the fact that many studies have been conducted in the field of criminal recidivism; most of them are tilted exclusively to one particular parameter of analysis. This study therefore looks at correlates from a holistic point of view in the sense that societal context, the institutional aspect (correctional) and the individual personal dispositions would be analysed as predictors of criminal recidivism. By focussing on the maximum correctional facilities in Kenya the study also targets behaviour of offenders who are at a relatively developed stage of their criminal career.

1.3 Purpose of the Study

The study investigated factors associated with the occurrence of criminal recidivism in Kamiti and Langata Maximum prisons, Nairobi County, Kenya.

1.4 The Objectives of the Study

The general purpose of the study was to determine the correlates of criminal recidivism. This research was guided by the following objectives:

Establish correctional factors influencing offender relapse using Risk, Need and Responsivity (RNR) Model as a lens.

Determine individual factors contributing to criminal relapse of offenders. Establish community factors contributing to criminal recidivism.

1.5 Study Hypothesis

The common statistical procedure for testing a postulate requires some understanding of a null hypothesis and considering the purpose and objectives of this study, the following

hypotheses were therefore tested:-

i) There is no significant relationship between Correctional Programming and offender‘s Risk factors.

ii) There is no significant relationship between Correctional Programming and offender‘s Need (criminogenic) factors

1.6 Justification and Significance of the Study

The level of criminal recidivism among convicted offenders released to the community is a persistent topic of public concern. In the administration of criminal justice, the extent to which the objectives of correctional, rehabilitative and reentry programs are achieved is dependent on information available to make public safety decisions and procedures employed. The study is important as it suggests ways of handling recidivist offenders and highlighting circumstances likely to propel them to re-offend. It also provides insights into the conditions under which the community is more or less likely to support offender re-entry.This makes it possible for both focuses on the development of rehabilitative/ treatments programmes that produce positive results and reentry mechanisms as they transition to the committee.

Formulation of treatment programmes for high risk repeat offenders can be deduced or reverse engineered from the factors that lead to criminal recidivism. This can also help develop counselling kit to help manage trauma of victims and inform potential victims to guard against future victimization.

In terms of prison rehabilitation program, the study findings have added knowledge on who to target, what to target, and how to target. If additional programmes are created, it could assist offenders with reducing their propensity to relapse back into crime thereby reducing the overall recidivism rates in the country. Effective programming and helping ex-offenders succeed in the job market has a potentially huge reach in dealing with poverty and social problems. The study findings are critical in providing correctional staff with evidence based information in determining operational policy and program implementation.

In addition, the study offers information to policy makers on gaps in rehabilitative services and programs used. By focusing on recidivists the study has shed light on situations this group of offenders confront while incarcerated and during post-release period. The result of this study could thus help in the implementation of strategies for social reintegration of inmates. The study has also revealed types of offenders who are recidivating, for what offences and how long after their release. All these are important for reentry planning.

resourceful in that programmes could assist them with successful reintegration into their respective communities.

Information on repeat offenders is crucial for accurately projecting the resources needed by various criminal justice agencies, including correctional facilities. Availability of data on repeat offenders also may generate new approaches to the problem of hardcore criminals. These approaches may include new sentencing practices targeted at those offenders who continue to threaten public safety through repeat criminal activity. The study also serves to narrow the academic gap that exists in this field thus adding into existing knowledge and also benefit scholars. It is also expected that the findings of the study may spur interest among other researchers to advance investigations in this area. At a broader level, the society may indirectly benefit from economically productive and less criminally oriented ex-prisoners.

1.7 Scope and Limitations of the Study

The study investigated factors associated with the occurrence of criminal recidivism in Kenya. The sample was drawn from Kamiti and Langata Prisons. The two facilities are maximum level prisons handling some of the very serious offenders in Kenya. This enabled the study to focus on serious public safety dynamics associated with recidivist offenders housed in these facilities.

of surveillance and restriction is much lower. They are also treated differently in terms of programming. Besides, by focusing on the reoffending of recidivist offenders, this research provides insight into the behavior of offenders who are at a relatively developed stage of their criminal career. Accordingly, the results of research cannot be generalized to whole range of criminal offenders.

1.8 Organization of the thesis

The thesis is organized into five chapters. Chapter one covers the introduction; chapter two the literature review, theoretical framework and conceptual framework model; chapter three the methodology; chapter four data analysis, presentation and discussion of the results while chapter five covers the summary, conclusions and recommendations of the study.

1.9Operational definition of terms

This section defines and clarifies key and new terms to be used in the study. After-care: Is less formal support following formal discharge.

Continuity of care: Commitment to providing consistent and support to the prisoners within and beyond the prison with holistic rehabilitative programs.

Court: Authority entitled to pass sentence in a criminal case and order for the detention of a person in custody for a particular case.

Criminal behavior: The conduct of an individual that leads to and including the commission of an unlawful act.

Desistance: Long term abstinence from criminal behavior among those who offending had become a pattern of behaviour

Ex-Offender: An individual who has been convicted of a crime and has been discharged after serving a prison sentence

High Risk offender: Offenders with higher probability of recidivating and displays the following characteristics: Hangs around with others who get into trouble, acts impulsively, never completes high school education and has difficulty maintaining employment among other things.

Impulsivity: A predisposition toward rapid, unplanned reaction to internal or external stimuli without regard to the negative consequences of these

reactions to the impulse individual or others Incarceration: The state of being imprisoned.

Inmate: Someone who is kept in a prison.

Intervention: Aims at minimizing re-offending after discharge by managing risk and promoting rehabilitation

Low Risk: Generally displays pro-social attributes and have low chances of recidivating. Need Principle: Programs to be directed towards the elimination of underlying issues that

push individual offenders to get involved in crime

Parole: The release of prisoners from prison custody to serve the remaining portion of their sentence in the community under constant supervision by authorized officers.

Post-release: The time following custody.

Public Safety: Is a condition specific to places in which persons and property are not at risk of attack and threat.

Recidivism: Is the reversion of an individual to criminal behavior, after he or she has been convicted of a prior offence, sentenced and (presumably) corrected on release.

Re-entry: Correctional programs that focus on the transition to the community and programs that have initiated some form of treatment in prison that is linked to community programs that will continue the treatment once the prisoner has been released.

Reintegration: A process resulting in outcome that include increased participation in social institutions such as labour force, families, communities , schools and religious institution.

Relevance: The extent to which correctional programs continue to realistically address inmate‘s actual need.

Responsivity: The internal and external factors that may impede on individual‘s response to intervention, such as weak motivation, program content or delivery.

Sex offence: Commission of acts of a sexual nature against a person without that persons consent.

Through care: The delivery of services in an integrated and seamless manner throughout a prisoner‘s sentence and release to the community

CHAPTER TWO

LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORITICAL FRAMEWORK 2.1 Introduction

This chapter is organized into themes drawn from study objectives. It consists of a review of related studies necessary in the understanding of factors associated with occurrence of criminal recidivism. It also presents the theoretical framework and conceptual framework.

2.2 Correctional System Factors Influencing Offender Relapse

A prison according to McCorkle and Thorn (1954) is a physical structure housing a number of people in a highly specialized condition where they utilize resources availed to them and adjust to the alternatives by a unique kind of social environment that is different from the larger society. Offender rehabilitation and reintegration is imperative in ensuring safe and secure communities. Many scholars such as Albertus (2010) and Polaschek (2012) argue that traditional approaches in combating crime in the past mostly favoured retribution and incarceration of offenders. As noted by Muntingh (2001) and Perry (2006),over 30 years of experimentation with the punitive and retributive approach have seen prison populations skyrocketing, leading to the conclusion that deterrence has hardly had any impact on reoffending and in some situations, actually increased it (Public Safety Canada, 2007).

manner that reduces the likelihood of reoffending. Padayachee, (2008) notes that offender reintegration as opposed to retributive punishment and imprisonment is aimed at protecting both offenders and society. In spite of the introduction of correctional programs, there is still an increase in cases of reoffending. Albertus (2010) argues that relapsing of ex-convicts is mainly due to the lack of support for their reintegration into society as law-abiding citizens, which in turn exacerbates the already increasing crime rate. While on the other hand, Gaum et al(2006) argues that recidivism is a result of intervention being introduced too late . The other point of view could be to do the failure of correctional programming in achieving the intended goal of rehabilitating inmates

rate of criminal recidivism in Nigeria in 2005 was 37.3%.The prevalence rate rose to 52.4% in 2010 as reported by Abifor. Kenya as is the case with other countries is also grappling with its share of high numbers of repeat offenders. This questions the rationale of sentencing objective since the period served as awarded by presiding magistrates and judges are deemed important to enable the offender to undergo various rehabilitative programs while in prison custody. Going by its mission statement of facilitating responsive administration of justice, rehabilitation and social reintegration, it is the expectation of the public that Kenya prisons service has done their part thus discharging a reformed individual back to a responsive community. This is not always the case as inmates relapse into crime and find themselves back to prison.

Within the correctional programs, proximate outcomes are cognitive and behavioral changes expected to result from participation in the intervention. As described by Motiuk (2006), an initial assessment of offender‘s risk and intervention needs is an important component of rehabilitative efforts. A correctional plan is developed from the initial assessment. An assessment maybe conducted using a variety of assessment instruments such as the Level of Service Inventory (LSI) (Andrew & Bonta, 1995) used by the Correctional service of Canada.

appropriately apply the principles of effective intervention. The principles are characterized as Risk, treatment and fidelity.

According to Fidelity principle, there are several factors that increase program effectiveness and are regarded as elements of programme integrity and/or quality. They include targeting responsivity factors like lack of motivation or barriers that can influence one‘s participation in programme, ensuring that the program has qualified and interpersonally sensitive staff who can closely monitor the offenders‘ whereabouts and be able to assist with offenders‘ other emerging needs and ascertaining that program is delivered as designed through quality assurance process, and structured aftercare.

assumption that ―correctional rehabilitation is usually resourced by and accountable to government; although offenders have rights to assistance with all aspects of functioning and correctional programmes are not mandated to address non-criminogenic needs‖ (Polaschek, 2012: 15). An effective program must therefore differentiate low risk from high risk offenders and identify factors linked to relapse and desistance before any programme design (Andrews, 2001). Higher risk offenders are in need of more intensive intervention whilst brief and narrowly focused programmes is recommended for lower risk offenders (Bonta, 1997 and Polaschek, 2012).

The need principle refers to the importance of programmes being aimed at the treatment of those dynamic needs proven to impact on recidivism. Focus of correctional treatment should therefore be on criminogenic needs like, substance abuse and employment problems. Criminogenic needs serve as treatment goals which, if successfully tackled, may reduce reoffending (Bonta 1997). Offenders have several needs deserving of treatment but not all are associated with criminal behavior. Criminogenic needs are subsumed under the major predictors of criminal behavior referred to as ―central eight‖ (Andrew&Bonta, 2006).

Polaschek (2012) contends that general responsivity refer to the use of general techniques and processes such as cognitive social learning methods to influence behavior. Specific responsivity, on the other hand leads to variations among offenders in styles and modes of service to which they respond. It takes into account learning style, personality, motivation, strengths, and bio-social variables such as race, gender and characteristics of the individual (Andrews, 2001).

The principle of professional discretion has also been advanced. It states that assessment instruments cannot be designed to cater for every single case. At times, there are those unique characteristics of an individual or situation that must be considered when making decisions about treatment. This means that there are times when the assessment tools might not indicate that an offender is low risk to re-offend, but special circumstances for example, behavior while in confinement may reveal existence of risk or probability of re-offending. However, many studies have indicated that properly completed, structured and objective assessment is more accurate and consistent than the judgment of professionals alone (Andrew & Bonta, 2002).

and responsivity remain at the core and have exerted a considerable influence on correctional theory, practice, and policy (Ogloff & Davis, 2004; Ward, Melser, & Yates, 2007).

Subsequently, Ward and his colleagues have expanded on what they call the good lives model- GLM (Ward, 2010; Ward & Gannon, 2008; Ward, Melzer, & Yates, 2007). Along the way, GLM has been described as a positive, strengths-based, and restorative alternative to the RNR model of offender rehabilitation. It also supplements RNR in the particular areas of offender motivation and personal identity (Ward, Melzer, & Yates, 2007) and a stauncher proponent of human rights than RNR (Ward & Birgden, 2004; Ward & Willis, 2010). It views offending as caused by an individual‘s inability to satisfy their basic human needs, such as relatedness or autonomy, through pro-social channels. Thus in this model, criminogenic needs are understood to be internal and external obstacles that frustrate the individual‘s ability to fulfill his/her basic human needs (Wards and Stewart 2003). Differentiating itself from RNRM, the GLM takes a broad approach at enhancing offender‘s capabilities.

weaken an offender‘s ties to their previous illicit network, but it can also strengthen them. The hope is that through life skills programming offenders can utilize prison as an opportunity to make the ―departure from a prior life of antisocial behavior‖ (Visher & Travis 2003, 107). Institutional programs designed to prepare offenders to re-enter society include education, mental health care, substance abuse treatment, job training counseling and mentoring. These programs are effective when they are centered on a full diagnostic assessment of offenders (Travis, 2000). For life skill education, this means assessing the offender based upon age, family status, substance abuse history, education and work. Programs and services are provided to equip the inmates with knowledge skills and experience to address existing problems (for example drug or addiction).

Decades of findings aggregated into meta-analysis have confirmed the relative importance of specific dynamic factors. The work of Andrews and his colleagues has ordered variables purported to be related to criminality and have identified the central eight risks/ need factors that are most important in understanding criminal behavior (i.e. prior antisocial behavior, antisocial attitudes, antisocial personality, antisocial associates, problematic circumstances in leisure/recreation time and substances misuse). Embedded within this group of variables is the big four (the first four listed above) which are proposed to be the major causal variables in the analysis of criminal behavior of individuals.

(McGuire, et al, 2008). Effective programs typically share certain features such as using behavioral and cognitive approaches, occurring in offenders natural environment, being multi modal and intensive enough to be effective, encompassing rewards for pro-social behavior, targeting high risk and high criminogenic need individuals and matching the learning styles and abilities of the offender(Allan, et al, 2000; Wilson & Mackenze, 2005).

According to Travis prison programming has played an important role in American corrections. Many prison administrators and others believe that providing educational and vocational programming to prisoners increases the likelihood of prisoner‘s successful return to the community. Studies support this rationale showing that a range of prison-based programming can contribute to positive post-release outcomes for prisoners, including reduced recidivism. In fact, research has shown that some of the most effective programs are those that combine in prison programming with after-care in the community.

Programme effectiveness has been reported by several studies. For example, La Vigne et al (2009) examined 210 male offenders‘ participation in programmes related to job training and education and were found to be less likely to recidivate. More specifically Vigne et al (2009) study concluded that offenders who took part in programmes designed to combat weakness may prevent or limit them and were better equipped to elude recidivating the first year of their release from prison Vigne et al (2009).Those who participated in programming designed to increase their level of education and vocational skills fared better in meeting their conditions of release and completing parole supervision than offenders who failed to participate (Hall, 2015. Hall et al 2000). In addition, programmes that offer a post release component that provides continuity in support help by assisting offenders as they pursue further education or re-enter workforce in the months immediately after release, (Hung En 2011,). Participation in correctional education is associated with a reduction in the odds of recidivism following release (Hall, 2015).

Securing legitimate employment can also provide a buffer to crime and delinquency (Sampson & Laub 1993; Salomon et al, 2004) and assist inmates as they are released. Re-entry programs often focus resources on employment given its importance in allowing the offender to be a productive member of the community. The prison industries that exist in many prisons nationwide dovetail nicely with this goal. In Kenya, a study by Awilly C.A (2015) on factors influencing recidivism at kingongo prison, Nyeri County focused on Vocational training and acquisition of skills in the light of Prison reforms. It established that ex-offenders lack capital to start up any income generating activities on release from prison custody. With the high rates of unemployment in third world countries, Kenya included, the lack of start-up capital for discharged inmates limits there effort to become productive citizens. The current study sheds light into the effectiveness of correctional programming in addressing the criminogenic factors of programme participants.

Many inmates in various studies have also been found to have problem with drugs. Most studies suggest that prison-based drug treatment can be effective in promoting re-entry back to the community and reducing relapse. For example, the evaluation of prison-based treatment in Minnesota found that it lowered recidivism from 17–25 percent (Duwe, 2010). The most promising outcome results have been found for offenders who complete prison-based treatment programs, especially those who participate in post-release after-care (Inciardi Martin & Butzin, 2004, Mitchell, et al, 2007).

Studies suggest that in prison family contact and post release family support contributes to minimizing recidivism (Barrick et al, 2014). The ability to maintain ties is thought to assist with reentry by normalizing the inmate‘s lifestyle and maintaining his or her perception of functioning as a member of a family unit (Goeting, 1982). The standard minimum rule on treatment of offenders clearly provides the general purpose of treatment of persons sentenced to imprisonment. Article 65 states that: - ―The treatment of prisoners sentenced to imprisonment or similar measure shall have as its purpose, so far as the length of sentence, permits, to establish in them the will to lead law abiding and self-supporting lives after their release and to fit them to do so. The treatment shall be such as will encourage their self-respect and develop their sense of responsibility.

While various demographic variables of age, employment are admittedly related, Orsagh and Chen (1988) considered the probability of offender recidivism to be functionally related to the time served in prison as a consequence of an offence. The data used related to 1,425 prisoners released from North American prison, and recidivistic outcomes were measured at the end of first and second years subsequently to their release. The researchers found support for their hypothesis that time served affects post prison recidivism rates. For burglars recidivism was found to be functionally to time served. On average, time served increased probability of robber‘s recidivating, suggesting that length of imprisonment did not serve as a deterrent: the effect was particularly strong for older offenders.

They concluded that the longer a person is removed from ‗outside‘ society, the weaker his or her social bonds. Weakened social bonds resulting from incarceration are likely to increase an offender‘s propensity to commit new crimes after release. Orsagh and Chen wrote; ―as the sentence becomes longer, expected legitimate earnings and employment opportunities decrease, because of the loss of contact with the job market, expected earnings and employment, interest in illegitimate activity increases‖. All these effects enhance post-prison criminal propensities.

classification, which is based almost entirely on past criminal behavior, predicted both prison misconduct and future arrests for federal inmates.

Level of security that the penal facility is ranked does have an influence at the rates at which prisoner will reoffend. A Study by Chen and Shiparo (2004) found that offenders coming out of high security ‗super max prisons demonstrate a higher rate of recidivism than those in lower security jails. Furthermore prisoners were more likely to commit a crime faster upon release than those who left non super-max facilities. It was also found that placing offenders in higher security classes has a significant effect on chances of rehabilitation, since contact with more violent offenders frequently encourages a criminal and even educates him or her to continue with a life of crime upon being released. New skills may be acquired, new elements and prospects may be learned of and further criminal contacts may be developed.

2.3 Individual Factors of an Offender

A number of studies points to employment status as a highly significant factor in predicting recidivism (Morgan, 1994: Sims and Jones, 1997). A study conducted by Jones (1997) found unemployment as one strongest predictors of failure. A North Carolina study determined that unstable employment, marital status and past convictions significantly predicted recidivism. According to Mpuag( 2001) most offenders in South Africa are unemployed, uneducated and impoverished which often pushes them to a life of crime. Employment plays a critical role in facilitating the reintegration of discharged offenders. As a protective factor, it directs would be criminals away from offending into a more pro- social role in society (Dector et al, 2015). Looking into the job skills of the respondents informs the study on extent of this criminogenic factor among the prison population

Research has consistently shown strong correlation between employment and reduction in future criminal behavior (Berg and Hueber, 2011). Returning offenders are faced with multitude obstacles in their attempt to gain employment (Brown 2011 b). Majority of returning offenders also face legal employment restrictions arising from Criminal records, (Harris & Keller 2005). The lack of employment predisposes former offenders to anti-social behavior and criminality in comparison to offenders who are able to find employment (Chamberlain 2012, Hall, 2015).

willingness to hire as brought out by Pager and Quillian, (2005). As brought out by Maruna and Immarigean, (2004) those offenders who experience discrimination after discharge from prisons have higher probability of recidivating. In another study, Tripodi et al (2010) examined the relationship between employment and recidivism. The study sought to determine as to whether getting employment by offenders on release decreased the odds and time spent in the community before re incarceration. The results of the study confirmed this. On their part, Pettit an Lyons( 2009) revealed that incarceration had significant negative effects on both employment and wage earning as time spent in prison being directly associated with deterioration in hourly earnings for men regardless of age (Pettit and Lyons 2009)

Low level of education especially in regard to high school dropouts also has a bearing in increased risk of recidivism (Albonnetti & Hepburn, 1997). By some measures, the less educated and less skilled the offenders, the more likely they are to recidivate. This theme repeats itself in a number of studies (Waller 1979, Grendreu and Andrews 1990: Andrew & Bonta 1994: Leone et al 2005).

Researchers have also examined the role that drugs play in the commission of crime. A US survey of inmates revealed that 19 percent of state prisoners and 16 percent of Federal inmates stated that they committed the offence for which they were incarcerated in order to obtain money for drugs (Mumola, 1999). Harlow (1993) also found out that one –third of prison inmates stated that they were under the influence of drugs at the time of the offence. Further , a national study of adult probationers revealed that two thirds of respondents used drugs at some point in their lives and nearly half were under the influence of a drugs or alcohol at the time of arrest their arrest ((Mimola & Boncar,1998).

The individual characteristics associated with recidivism among sexual offenders have been previously reviewed (Hanson & Busiere 1998, Hanson &Morton Bourgo, 2005). In general the two broad domains associated with sexual recidivism are sexual deviancy and lifestyle instability/criminality. The criminal lifestyle characteristics (e.g. history of rule violation, substance abuse) are most strongly related to violent and general recidivism among sexual offenders (Hanson &Morton-Bourgon, 2004). Returning prisoners‘ attachment to society such as employment and family relationships are relatively weak. According to Lynch and Sabol (1997), the comparison of four measures of social integration among a cohort of soon to be released offenders for 1991 and 1997, depict minimal change in reported marital status, education, employment and children. About one-quarter of the offenders was divorced and nearly 60 percent were never married, about one-third of the offenders were unemployed prior to prison entry and two-thirds of the offenders had not completed high school.

2.4 Community Factors Affecting Criminal Recidivism

The effect that the environment has on the individual returning back to community after being incarcerated, can determine if the individual‘s reintegration will be successful or not. Tillyear Vose (2011) state that the community setting which an ex-offender returns is crucial in developing an explanation about recidivism. This is based on the fact that many individuals being discharged from prisons are not returning to nurturing environments. Many return to homes that are shared with other individuals who engage in criminal activities, in chaotic communities, or communities that have a lack of community resources (Bellair& Kowalski, 2011).

John Irwin (1970) identified a three part component of an offender‘s return to the community. The first part is when the offender begins to ―get settled down or get on your feet‖. During the initial period of return, they realize the difficulties of getting adjusted. Normal survival, functions like clothing, residence, transportation, employment and food dominate the offender efforts. Coupled with this is the initial impact of disorientation, which can be unsettling, as the offender has to restate ―his position with family, peers and others. The next part is either ‗get by‘ or ‗make it‘ phase. After the initial settling down phase, the offender is confronted with the reality of maintaining him/herself. The search for meaning is coupled with frustrations of re-establishing the position and becoming satisfied with new life. During this phase, the offender must overcome the stigma of being an ex-offender, address vocational deficiencies and establish gratifying relationships. They return in the community with grand expectations about their prospects, and their revived role as a citizen in the community. The offender must then try to manage a citizenship role while being ―Less of a citizen ―(Uggen and others, 2003 pg. 37) as described by Irwin (1970) and furthered by Maruna (2001), the pathway to an outcast is far easier for many offenders than trying to overcome the obstacles to being a citizen.

Among the many challenges facing prisoners as they return home is their reunification with family. For most former prisoners, relationships with family members are critical to successful reintegration. Family plays an intricate part in fueling pro-social behavior and provides a strong foundation that facilitates an offender‘s desire to resist criminal behavior( Bales & Mears, 2008, Berg 2011). Research has however, documented that many family members of returning prisoners are wary about their loved ones‘ return from prison and that a significant adjustment in roles is often necessary (Haggan and Dinovitzer 1999). The family often expects the offender to repay the resources consumed while the offender was incarcerated, and to assume a pivotal role in the family. Some offenders prefer to delay re-uniting with the family to ease the pressure, (Young and colleagues, 2003), while others merely reunite with family while rejecting the demands to contribute to the family. Research has consistently showed that having a strong support system aids in the transitional process of adjusting back to the community. Former prisoners often need and receive assistance from families that center around helping them with employment, housing, financial stability and emotional support (Martines , 2006, Naser and La Vigne, 2006)

on discharge. It revealed that offenders relied on their family members in gaining housing, financial and emotional support during reintegration process and their expectation in gaining such assistance exceeded what was expected of their family. Their study concluded that family is a vital resource in adjusting in the community and works as a protective factor that buffers against the challenging obstacles and barriers offenders face during the initial process of reentry and parole (Nasser& La Vigne, 2006). In terms of social capital, families also assist discharged offenders in improving outcomes. The social networking helps in locating job opportunities and can also convince employers that offenders are employable and trustworthy (Berg & Hueber, 2011).

Real or imagined discrimination and stigmatization within community has an effect on the former offender. Requirements of probation, such as, weekly reporting and drug screening are also barriers to effective employment searches. Drugs and alcohol abuse can be detrimental to the former offender‘s attempt to reintegrate, causing housing, social and family problems, reducing the social support necessary for reentry (Graffam et al, 2004).

highly significant factor in predicting recidivism ( Morgan,1994: Sims and Jones, 1997 ) A study conducted by Jones (1997) analyzed a sample of 307 offenders and found unemployment as one strongest predictors of failures. A North Carolina study determined that unstable employment, past convictions and marital status significantly predicted recidivism.

Not surprisingly, ex-offenders rely on neighborhood resources, services and amenities to successfully reintegrate. Today more than ever, they rely on their neighborhood, in large part; they leave prison with serious social and medical problems and face substantial reintegration barriers. Offenders returning to unsafe neighborhood lacking in social capital are not only less likely to be employed but are also at a greater risk of recidivism (Visher and Farrell 2005). Indeed Kubrin and Stewart (2006) found that higher rates of recidivism were associated with neighborhoods that were more disadvantaged. In 2008 a study, Mears and colleague found that resource deprivation (Median family income, female – headed households, unemployment and poverty levels) significantly increased violent recidivism.

Offenders released from prison generally receive little pre-release support in securing accommodation and are often unable to find suitable living arrangement. Several find themselves in unstable housing, which can cause challenges in maintaining their freedom. This population may engage in illegal activity to provide housing for his or her family or any other people that the individual supports. Matrious et al (2010), report that lack of stable housing may in turn perpetuate the cycle of criminal behavior. Social isolation is a core experience of many ex-prisoners who may end up homeless or with unstable offenders (Balding et al 2002; Lewis et al 2003). Families represent an important support system for offenders both while incarcerated in prison and in the community .Their absence can have a significant effect on the offender‘s family structure and the long term risk of future criminal behavior by the offender‘s child. Marital relationships are often strained and more likely to end in divorce for a variety of reasons including financial hardship lack in emotional support or simply the stress of having absent spouse (Travis, et al, 2003).