ABSTRACT

GIBSON, STEPHEN MICHAEL. Where Do I Belong?: An Investigation into the Impact of Racial Microaggressions on African American College Students (Under the direction of Dr. Jessica T. DeCuir-Gunby).

African Americans often feel isolated and out of place at their respective universities (Smith et al.,

2007). Furthermore, African American students at Predominantly White Institutions (PWIs) often

view their campuses as hostile and not culturally affirming due to racial microaggressions. For

many African American particularly within the educational context, racial identity serves as a

protective factor when experiencing racial microaggressions. Moreover, African American college

students must engage in specific coping strategies that enable them to achieve academic success

even despite negative race-related and high levels of stress experienced on campuses (Greer &

Chawalisz, 2007). This quantitative study investigated the relationships between racial

microaggressions, coping strategies, and racial identity. Results indicated that African American

college students’ sense of racial pride served as a protective factor when experiencing racial

microaggressions. Moreover, this line of research has implications for innovations in educational

and teaching practice, counseling practices on college campuses, and diversity training for students

© Copyright 2019 by Stephen Gibson

Where Do I Belong?: An Investigation into the Impact of Racial Microaggressions on African American College Students

by

Stephen Michael Gibson

A thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University

in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of

Master of Science

Curriculum & Instruction

Raleigh, North Carolina 2019

APPROVED BY:

Dr. Jessica T. DeCuir-Gunby Dr. DeLeon Gray

Committee Chair

ii

DEDICATION

This document is dedicated to Charles and Mary Gibson

Dad and mom, you sacrificed so much for me to be here. I know that raising my brothers

and me was not an easy task, but you made it looks effortless. Throughout the years, you have

taught me to be a man of character and integrity that is hard-working, responsible, and above all

a good person. I hope this document makes you proud. I pray that my graduate school and

research journey fills your heart with love and makes you proud of the little boy you turned into

a man.

Your son,

iii

BIOGRAPHY

Stephen Gibson is a native of New Orleans, Louisiana, but currently resides in Durham,

North Carolina. He received a B.A. in Psychology with a concentration in Community Psychology

in 2016 from North Carolina Central University. Prior to graduate school, Stephen was hired as

the Project Manager in the Wilbourn Infant Lab at Duke University under the direction of Dr.

Makeba Wilbourn. As the project manager, Stephen assisted with research projects, recruitment

efforts, and mentoring undergraduates through their research journey, while being the Co-Director

of the Wilbourn Infant Lab Summer Internship.

Currently, Stephen is a Masters student in the department of Teacher Education and

Learning Sciences. He is working on his Master’s degree in Curriculum & Instruction with a

concentration in educational psychology, with plans of continuing his research as a doctoral

student in Developmental Psychology at Virginia Commonwealth University. In addition to

dedicating himself to his research and coursework, Stephen is a Graduate Research Assistant under

Dr. Jessica DeCuir-Gunby and in the North Carolina State University Fatherhood Research Lab

iv

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First, I would like to express my gratitude to my thesis advisor, Dr. Jessica DeCuir-Gunby,

for her guidance and support throughout this lengthy and intensive process. I appreciate your

guidance and your feedback have been instrumental in helping me in this endeavor. In addition, I

would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Deleon Gray and Dr. Elan Hope for their time

and thoughtful feedback. Also, I want to thank Ms. Irene Armstrong for all of her support and

emails. I appreciate all of the emails and meetings to make this document possible.

Secondly, I would like to give a special thanks and express my gratitude my fellow cohort

and colleagues - Jerica, Whitney, McKenzie, Briana, and Erin – for their moral support and

encouragement. Without all of the laughs and deep conversations, I will not be here. Furthermore,

I want to express thanks to my brothers for always being there for me.

Thirdly, I want to thank all of the professors – Gary Bennett and Martin Smith - that have

guided me with support and advice throughout this process. In addition, I want give special thanks

to the many professors that gave me opportunities after opportunity to work in their labs and on

multiple projects – Makeba Wilbourn, Primula Lane, Sarah Gaither, Qiana Cryer-Coupet, Shauna

Cooper, Angela Wiseman - each experience have touched and made a huge difference in my

growth and development as a researcher.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF TABLES ... vii

LIST OF FIGURES ... viii

Chapter 1: Introduction ...1

College Campuses and African American Students ...2

What about Racial Microaggressions? ...4

Racial Microaggressions and Coping Strategies ...5

Racial Microaggressions and Racial identity ...7

Sense of Belonging...8

Conceptual Framework: Impact of Racial Microaggressions on African American College Students ...10

Chapter 2: Methods ...12

Participants ...14

Measures...17

Data Collection Procedures ...18

Data Analysis ...19

Chapter 3: Results...20

Preliminary Analysis ...20

Main Analysis: First Goal ...20

Main Analysis: Second Goal ...22

Main Analysis: Third Goal ...27

Chapter 4: Discussion ...29

Implications ...31

Limitations and Future Directions...32

Conclusions ...33

References ...34

vi

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics for College Racial Microaggression Data Set ...16 Table 2 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for

College Racial Microaggressions Data Set ...20 Table 3 Hierarchical Regression Model Predicting Sense of Belonging

as a function of Public Regard ...24 Table 4 Hierarchical Regression Model Predicting Sense of Belonging

vii

LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1 Representation of the relationships between racial

identity, educational advocacy, racial microaggressions

and sense of belonging ...11 Figure 2 Mean scores of microinsults experiences for

undergraduate and graduate African American students ...21 Figure 3 Mean scores of microinvalidations experiences for

undergraduate and graduate African American students ...22 Figure 4 Interaction of private regard by microinsults experiences

in predicting self-reported sense of belonging ...25 Figure 5 Standardize mediational pathways from racial microaggressions

1

CHAPTER I Introduction

African Americans regularly face bias, prejudice, and discrimination in both academic and

social settings on college campuses (Franklin, Smith, & Hung, 2014; McCabe, 2009; Suyemoto et

al., 2009). The experience of racism and racial discrimination plays a key role in explaining that

African-American undergraduates students have lower graduation and retention rates than their

White peers (Grier-Reed, 2010; Brezinski et al., 2018; Wells, 2008). Empirical findings suggest

African American college students, attending predominantly White institutions (PWIs) are

exposed and experience racially insensitive covert and overt behavior such as racial discrimination,

racial slurs, and racial exclusion. In one study, an astounding 98.5% of African American graduate

and undergraduate students experienced racial discrimination on their college campuses (Prelow,

Mosher, & Bowman, 2006). Previous research has found that microaggressions emerged as the

most relevant form of discrimination within physical settings (Sue et al., 2007). Furthermore, recent

literature suggests racial microaggressions negatively influences the lives of African American

college students (Grier-Reed, 2010; Henson et al., 2013; Lewis et al., 2013). D’Augelli and

Hershberger (1993) propose negative and pervasive racial experiences, such as discrimination and

microaggressions, are taxing for African American college students and results in lower levels of

academic success in the college environment.

Racial Microaggressions have real consequences in both academic and social spaces for

African American college students (Solórzano et al., 2000). Solórzano, Ceja, & Yosso (2000)

suggests that collegiate racial climate fosters more subtle racism within academic environments

compared to overt racism, whereas more overt racism actions are exhibited within social spaces

2

and lack of racial community within the college campuses are all elements that contribute to

African American students feeling of self-doubt, frustration, and isolation (Solórzano, Ceja, &

Yosso, 2000). Furthermore, African American college students must strive for good academic

performance while combatting negative racial stereotypes that create and perpetuate racial

microaggressions. Thus, the goal of this manuscript is to explore the experiences of African

American college students on PWI campuses with racial microaggressions, and its impact on

students’ sense of racial identity, sense of belonging, and elected coping strategies used to combat

these experiences.

College Campuses and African American Students

Empirical research focusing on African American college experiences at PWIs have

primarily concentrated on differential experiences relative to White students (Allen, 1992), African

American students attending an historically Black college (Fleming, 1984), and the racial

composition of their respective college campuses (Ancis, Sedlacek, Mohr, 2000). A breadth of

empirical research has investigated the comparison between African American college experiences

at PWI campuses and their White counterparts along many factors such as persistence rates,

academic achievement, postgraduate study, and overall psychological adjustments (Allen et al.,

1991; Astin, 1982; Fleming, 1984; Hall, Mays, Allen, 1984; Nettles, 1988; Thomas, 1981). A

recent trend of literature have focused on the African American perception of school racial climate

at postsecondary institutions (Chavous, 2005; Hurtado et al., 2008). Campus racial climate is

associated with students’ academic and social life within the college context (Hurtado et al., 2008,

p. 205). African American college students at PWI campuses face several difficulties, such as

isolation, alienation, and lack of support from faculty and administrators; moreover, forcing

3

Campus climate can be broadly defined as the overall racial environment of the college

campus (Solórzano, Ceja, & Yosso, 2000). An existing body of literature have investigated and

concluded when collegiate racial climate is positive the campuses consist of the following

elements: inclusion of students of color and programs to support the recruitment, retention, and

graduation of students of color. (Carroll, 1998; Guiner et al., 1997; Hurtado, 1992; Hurtado et al,

1998). Solórzano and Yosso (2000) suggest positive college racial climate can facilitate positive

academic outcomes for African American students; in contrast, negative racial climate have been

linked to poor academic performance and high dropout rates (Allen, Epps, & Haniff, 1991).

African American students frequently view the campus racial climate at PWIs as negative (Pieterse

et al., 2010). One potential explanation is African American students at PWIs reported negative

relationships with faculty members and White peers, thus avoiding interactions with faculty and

peers outside of the classroom.

Campus environments’ influences on the educational outcomes and experiences of African

American college students have been a consistent thread in research (Allen et al, 1991). Previous

literature investigating school climate suggest that attending a hostile school racial climate can

result in African American and other students of color’s sense of connection to school decreasing,

even if they value the outcomes of education (Booker, 2006). School racial climate is viewed

influential for African American students due to the salience of race in their lives (Booker, 2006;

Mattison & Aber, 2007). Students’ perceptions of school racial climate and experiencing racial

microaggressions on PWI campuses can negatively impact students’ sense of belonging and

decrease academic performance. Consequently, African American students can potentially

4

What about Racial Microaggressions?

Racial Microaggressions are brief and commonplace, interpersonal exchanges, intentional

and unintentional, communicate denigrating and disparaging messages to ethnic minority

individuals (Sue et al., 2007). Racial microaggressions serve as daily reminders that one’s race and

ethnicity is an ongoing ‘stimulus in the world’ (Harrell, 2000). Experiencing a racial

microaggression may be manifested behaviorally or verbally (Torres et al., 2010).

Microaggressions can be experienced in multiple forms: microassaults, microinsults, and

microinvalidations. Unlike microassaults that involve overt behavior, microinsults and

microinvalidations include subtle and ambiguous discriminatory situations (Torres et al., 2010).

Subtle forms of racial microaggressions can be more harmful than blatant acts of microaggressions

due to their ambiguous nature (Torres et al., 2010; Sue et al., 2008). Due to the ambiguous nature,

these acts can leave the targeted individual in a confused state (Breziniski et al., 2018). For African

Americans, this state can lead to a decrease in academic performance (Solórzano et al., 2000; Sue

et al., 2008).

Microinsults are subtle, indirect verbal and nonverbal behaviors that convey stereotypical

beliefs that convey a hidden insulting message to the recipient of color (Sue et al., 2007, page 274).

Microinsults include behaviors that convey or perceived as ascription of intelligence, assumption

of criminal status, pathologizing cultural values/communication styles, and second-class

citizenship (Torres et al., 2010). Microinsults are used to indirectly insult an individual’s racial

identity or racial heritage by offering a compliment that was received negatively (DeCuir-Gunby

& Gunby, Jr., 2016). Microinvalidations can be defined as statements that tend to “exclude, negate,

or nullify the psychological thoughts, or feelings or experiential reality of a person of color” (Sue

5

experiences as racial/ cultural beings (Helms, 1990).

Racial Microaggressions take various forms, verbal and nonverbal assumptions, for

African American students (Solórzano, Ceja, & Yosso, 2000). Racial Microaggressions, within the

academic setting, are often filtered through layers of racial stereotypes of academic inferiority of

African American students in comparison to their White counterparts. African American students

commonly combat racial microaggressions from administrators, professors, peers, and the

curriculum (Baber, 2012; Cabrera, 2014; Johnson-Ahorlu, 2013). A breadth of research

investigating racial microaggressions within the college context have focused primarily on African

American undergraduates (Brezinski, 2018; McCabe 2009; Forrest-Bank et al., 2015; Harrell,

2000) and African American college students overall (Robinson-Wood et al., 2018; Solórzano,

Ceja, & Yosso, 2000; Hardwood et al., 2012; Torres et al., 2010; Sue et al., 2007). As a result, there

is dearth of literature that focuses on the types and frequency of racial microaggressions

experienced by graduate students. In addition, there is a lack of quantitative research that explores

the impact of racial microaggression on graduate students of color, specifically African American

students (Ortiz-Frontera, 2013). African Americans must learn to cope while negotiating their

environments; however, doing so can be particularly challenging in PWI contexts because of

experiences with racial microaggressions (Mitchell, Fasching-Varner, Albert, & Allen, 2015).

Racial Microaggressions and Coping Strategies

Compas et al., (2001, p.89) defined coping as, “conscious, volitional efforts to regulate

emotions, behaviors, physiology, and the environment in a response of stressful events or

circumstances.” Previous literature has highlighted that African American college students on PWI

campuses experience traditional college stressors (e.g. financial problems); however, these

6

microaggressions (L.P. Anderson, 1991; Thoits, 1991). Coping has been found to mediate the

effects of stress. Coping with racism involves the effort used to solve or minimize stress or conflict

(Thomas, Witherspoon, & Speight, 2008). African American college students must engage in

specific coping strategies that enable them to achieve academic success even despite negative race-

related and high levels of stress experienced on campuses (Greer & Chawalisz, 2007).

Finding the appropriate coping mechanisms that are appealing in a non-supportive

environment can be a difficult task (Holder et al., 2015). Several studies have found that specific

coping strategies serve as a buffer against the negative association between racially stressful events

(Gaylord-Harden & Cunningham, 2009; Noh et al., 1999). However, utilizing effective coping

strategies can help African Americans address racial microaggressions and oppression in addition

to impact their overall physiological health (Franklin & Franklin-Boyd, 2000; Holder et al., 2015).

Two traditional approaches to understanding coping strategies are adaptive and maladaptive

coping (Suls & Fletcher, 1985).

Adaptive coping strategies are the positive or healthy approaches to addressing stress such

as engaging in communication or confronting racism and seeking mentorship, networks, and safe

spaces (Holder et al., 2015; Franklin & Boyd-Franklin, 2000). Miller and Kaiser (2001) observed

coping with racial discrimination and other racial stressors may manifest in collective individual

actions such as: educational, advocacy, and lobbying efforts. Utilizing education as an adaptive

mechanism can educate the aggressor of the intentional or unintentional racial microaggression

while defending the recipient's personal rights. Mellor (2004) suggested that educating the

aggressor as a coping strategy can serve as an effort to prove the aggressor wrong by challenging

ignorant thoughts and beliefs and asserting their right to equal treatment. Sue and colleagues

7

intervention. Moreover, the process of educating the aggressor benefits victims by asserting pride

in their own racial/ethnic identity and denying their identity for self-protection.

Racial Microaggressions and Racial identity

Racial identity can be defined as the significance and meaning of race in individuals’ lives

(Sellers et al., 1998). Cross et al. (1998) hypothesized the primary function for African Americans’

racial identity is to buffer negative impact of experiencing racial discrimination. A breadth of

research has suggested the association of racial identity development and psychosocial outcomes

as well as the potential of racial identity beliefs to buffer against negative effects of racial

discrimination among Black emerging adults (Caldwell et al., 2004; Sellers et al., 2003; Sellers &

Shelton, 2003; Wong et al., 2003). Brondolo et al. (2009) suggested that positive racial identity is

linked to positive academic outcomes when experiencing different forms of racism. For many

African American particularly within the educational context, racial identity serves as a protective

factor when experiencing racial microaggressions.

Previous research suggests racial regard serves as a protective factor for African Americans

from adverse consequences of perceived discrimination (Branscombe et al., 1999). Moreover, this

racial identity model hypothesizes an individuals’ worldview of the African American community

can serve as a buffer when experiencing racial discrimination. Sellers (1998) suggests racial regard

measures the extent to which an individual feels positively about his or her race. This dimension

involves two components—public and private regard. Public regard refers to one’s perceptions of

how society views the African American community. Previous research highlights public regard

as a moderator for the relationship between perceived racial discrimination and mental health

(Sellers & Shelton 2003). Furthermore, an existing body of literature has suggested low public

8

outcomes (Chavous et al., 2008; Oyserman et al., 2001; Sellers et al., 2003; Sellers, Copeland-

Linder, Martin, & Lewis, 2006; Wong et al., 2003). Low public regard suggests negative opinions

of the African American community from the broader society. As a result, African Americans,

with low public regard, may be less affected when experiencing perceived racial discrimination in

comparison to African Americans with high public regard, due to the consistent racial worldview

(Sellers et al., 2003). Low public regard may serve as a protective factor for Black college students

due to the recognition of negative views of one’s racial-ethnic group (Keels et al. 2017). Moreover,

African Americans with high public regard are less likely to think that the broader society would

treat them negatively because of their inconsistent worldview (Sellers & Shelton, 2003).

Private regard is defined as the extent to which individuals feel, positively or negatively,

towards African Americans and about being an African American (Sellers et al., 1998). Private

regard has been closely linked to racial pride and psychological closeness. High private regard

suggests an individual's positive feeling about being African American and the overall African

American community; however, low private regard is associated with an individual’s negative

views about being a part of the African American community. Nevertheless, having a strong or

positive sense of racial identity can buffer African Americans’ experiences with racial

microaggressions and its impact on their psychological needs. Current works of literature reveals

African American students’ sense of racial identity can promote or deter students’ sense of

belonging and can impact academic engagement (Gray, Hope, Matthews, 2018; Hope et al., 2013;

Smalls et al., 2007).

Sense of Belonging

According to Deci and Ryan (2000), all humans have three basic psychological needs:

9

belonging is an essential factor throughout life and within the academic setting. Furthermore, the

need for belonging is a necessity in order to motivate, be motivated, and achieve or thrive during

a task (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). A sense of belonging for students can be defined as the extent

to which students feel personally accepted, respected, included, and supported by others within the

school environment (Goodenow, 1993). The need for social belonging is a basic human motivation

(Baumeister & Leary, 1995; MacDonald & Leary, 2005). Previous research broadly defines school

belonging as perceptions of acceptance, respect, inclusion, and support (Goodenow, 1993).

Moreover, students’ sense of belonging at school serves as a protective factor academically

(Freeman, Anderman, & Jensen, 2007; McMahon, Wernsman, & Rose, 2009) and psychologically

(Matthews, Banerjee, & Lauermann, 2014).

Prior research of school belonging suggests that students’ race and ethnicity are pivotal

factors in the way students perceive and interpret school environments (Juvonen, 2007). Moreover,

African Americans in academic contexts are often stigmatized in circumstances that threaten their

sense of school belonging (Walton & Cohen, 2007). Gray, Hope and Matthews (2018) offers a

deeper exploration of school belonging for African American students by presenting broader

perspectives encompassing interpersonal, instructional, and institutional opportunity structures.

Furthermore, existing research has investigated the impact of social factors, such as students’ sense

of racial identity on students’ sense of belonging in academic settings. African American students,

due to the stigmatized circumstances, have heightened the risk of being the target of disconfirming

messages about belonging in academic spaces (Cohen & Garcia, 2008; Cook, Purdie-Vaughns,

10

Conceptual Framework: Impact of Racial Microaggressions on African American College Students

Based on Deci and Ryan (2008), everyone has needs that must be met at the psychological

level thus impacting their interactions. Therefore, in the collegiate setting, students need these to

be met to satisfy their personal well-being, growth, and performance in the academic setting.

Previous research has examined the impact of racial microaggressions on their academic

involvements, campus experiences, and emotional and physical health (Gomez, Khurshid, Freitag,

& Lachuk, 2011; Harwood et. al 2012; Yosso, Smith, Ceja, & Solórzano, 2009). Experiencing

racial microaggressions can place a strain on African American students’ academic involvements,

interactions, and feelings of belonging in the college context. Particularly within the educational

context, positive racial identity has been associated with positive academic outcomes and

achievements (Harper, 2007; Thomas, Caldwell, Faison, & Jackson, 2009).

African American college students often feel alone in academic and social settings as they

experience racial microaggressions in the classroom and social spaces on campuses. Consequently,

African Americans often feel isolated and out of place at their respective universities (Smith et al.,

2007; Solórzano, 1998; Solórzano, Ceja, & Yosso, 2000). Moreover, African American college

students often view PWIs as hostile and not culturally affirming. As a result, when African

American students experience racial microaggressions, their sense of racial identity is challenged,

which triggers coping mechanisms, often in negative ways, causing detrimental effects and

simultaneously decreasing their sense of belonging.

Understanding African American college students’ experiences with racial

microaggressions is a complicated process. There is existing literature on African Americans’

11

Solórzano et al., 2000). In addition to this body of literature, there is empirical research focusing

on the impact racial microaggressions have on African American students’ perceptions of school

climate at predominately white universities (Booker, 2006; Mattison & Aber, 2007). Furthermore,

empirical research suggests that racial identity serves as protective and mediating factors for

African Americans within academic settings when experiencing racial discrimination (Sellers &

Shelton, 2003; Mellor, 2004). However, limited research has investigated the link between racial

microaggression experiences and African American college students’ sense of belonging as

protective and mediating factors at predominately white universities. Based upon the body of

literature discussed, I conceptualize that racial microaggressions are directly associated with sense

of belonging for African American college students. In addition, students’ sense of racial identity

(e.g. public regard and private regard) will moderate this relationship, while educational advocacy

as a coping strategy will mediate this relationship (see Figure 1).

12

CHAPTER II Methods

The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of African American college

students with racial microaggressions within the PWI college context. A PWI is an institution at

which White students make up for 50 percent of more of the student body (Brown & Dancy, 2009).

The first goal was to explore how specific groups of African Americans’ students experienced

racial microaggressions including how experiencing racial microaggressions impacted African

American college students’ sense of belonging on PWI campuses within the college context. The

second goal was to examine how African American college students’ social factors such as the

sense of racial identity and coping strategies influenced the relationship between experiencing

racial microaggressions and sense of belonging for African American college students. Lastly, my

final goal was to explore the effects of racial microaggressions, racial identity, and coping on

African American students’ sense of belonging within a PWI context. I specifically explored the

following research questions:

Research Question 1: Do African American undergraduates experience more microinsults and

microinvalidations than African American graduate students?

Hypothesis 1: African Americans undergraduate students will experience more racial

microaggressions than African American graduate students. Enrollment in college for African

Americans has steadily increase since 2005 (USA Department of Education, 2015). As a result,

college campuses have become more racially/ethnically diverse. This growth has led to an increase

in opportunities to experience racial discrimination (Rothman et al., 2013). Previous research

proposes that campus life, safe spaces, and residence halls are important socializing factors for

13

more time and interactions with peers due to these socializing factors in comparison to graduate

students. Therefore, I hypothesized that African American undergraduate students perceive more

microinvalidations and microinsults regarding their race in comparison to African American

graduate students.

Research Question 2: Do African American college students’ sense of private and public regard

moderate the relationship between experiencing a microinvalidations and students’ sense of

belonging?

Hypothesis 2: Microinvalidations behaviors include negating and nullifying African Americans’

experiences as racial/cultural beings (Helms, 1990), such behaviors can negatively impact African

Americans’ sense of belonging. Previous research suggests African Americans students’ sense of

racial identity can serve as a protective factor when facing racial discrimination and forms of

racism. Public regard reflects an individual’s perception of how others view the African Americans

community, positively or negatively (Seller et al., 1998), while private regard taps into an

individuals’ racial pride in being a part of the African American community (Chavous et al., 2003).

Sense of public and private regard measures African American perception of worldview regarding

the African American community. As a result, experiencing a microinvalidation will confirm or

refute African American students’ worldview about African Americans. Moreover, students that

report lower scores on public regard or higher scores on private regard will buffer the impact racial

microaggressions have on their sense of belonging. Therefore, I hypothesized that African

American college students’ sense of public and private regard will moderate the relationship

between racial microaggressions and sense of belonging.

Research Question 3: What is the extent does educational advocacy mediate the relationship

14

Hypothesis 3: Experiencing racial microaggressions, specifically microinsults, can place a strain

on African American students’ academic involvements, interactions, and feelings of belonging in

the college context. Microinsults convey rudeness, insensitivity, or otherwise demeaning behaviors

that can be detrimental to African American students (Torres et al., 2018). As a result, African

American college students may have feelings of racial exclusion which leads to feelings of

isolation on PWI campuses. Such feelings of isolation due to racial microaggressions forces

African American college students to elicit mechanisms to cope with such experiences. I

hypothesized educational advocacy, an adaptive coping strategy, will mediate the relationship of

racial microaggressions experiences and African American college students’ sense of belonging.

Research Question 4: What is the effect of educational advocacy, microinsult, public regard, and

private regard on belonging?

Hypothesis 4: African American college students who report high levels of educational advocacy,

high private regard, high experiences of microinsults, and low public regard will not report high

levels of belonging. In the college setting, students may attend social and academic events as part

of their college experience to feel connected to the campus; however, African Americans who

report lower levels of belonging will not perceive their campus climate as culturally affirming.

African American college students with high private regard feel connected to their racial

community and will utilize education and advocacy as coping strategies; in addition, these students

may have perceived the low regard society has for the African American community and

experience more microinsults.

Participants

Participants were 97 college students who consented to participate in a broad investigation

15

college students from various Predominately White Institutions. Demographics and descriptive

statistics were analysis (see table 1) and further discussed. Of the participants, 77% identified as

female and approximately 82% of the sample attended a university with greater than 15,000

students. About 81% of the sample attend a university with racial composition of at least 20% of

people of color at such university. Of the participants, about 94% of the sample identified as full

time undergraduate and graduate student and 88% attend a public university. Of the sample, 40%

identified as graduate students and 60% identified as undergraduate students. For the

undergraduate student sample, 9% identified as a freshman, 13% classified as sophomore, 14%

identified as a junior, and 23% classified as a senior. Approximately 26% of the sample identified

16

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for College Racial Microaggression Data Set.

Characteristic Number Percent

Gender

Male 22 22.68

Female 75 77.32

Income

$0-$9,999 10 10.42

$10,000-$29,999 23 23.96

$30,000-$59,999 29 30.21

$60,000-$99,999 16 16.67

$100,000-$199,999 12 12.50

$200,000-$499,999 4 4.17

$500,000+ 2 2.08

Education

Freshman 9 9.28

Sophomore 13 13.40

Junior 14 14.43

Senior 22 22.68

Graduate Student 36 37.11

Professional Student 3 3.09

Racial Distribution of University

Less than 5% people of color 4 4.12

5% people of color 19 19.59

10% people of color 31 31.96

15% people of color 16 16.49

20% people of color 10 10.31

25% people of color 9 9.28

30% people of color 3 3.09

35% people of color 1 1.03

40% people of color 2 2.06

50% people of color 2 2.06

Size of University

Less than 5,000 Students 7 7.22

5,000 to 15,000 students 10 10.31

Greater than 15,000 students 80 82.47

Member of an African American Greek Organization

Yes 25 25.77

No 72 74.23

17

Measures

Participants were asked to respond to six different instruments including: demographics

questionnaire, the Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale (Nadal, 2011), the Coping With

Discrimination Scale (Wei et al, 2010), the Emotional Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John,

2003), the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (Sellers et al.1998), and the Basic Need

Satisfaction in General Scale (Deci & Ryan, 2000). These measures were utilized to elicit an

understanding regarding the participants’ various experiences.

Demographics Questionnaire

The demographics questionnaire included questions regarding personal characteristics and

issues such as: age, gender, classification, and major. Additional questions addressed the university

context.

Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale

The Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale (Nadal, 2011) was designed to examine the

experiencing of various types of racial microaggressions in multiple contexts. This scale was used

to assess African American college students’ experiences with racial microaggressions. I focused

on two of the subscales: Assumptions of Inferiority and Microinvalidations. Assumptions of

Inferiority accounted for students’ experiences with microinsults.

Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity

The Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (MIBI) was developed to explore the

multidimensionality of Black identity and uses a 7 point-Likert format (Sellers et al, 1997). For

this study, the Racial Regard scale (e.g. private and public regard) was used to explore African

18

Coping with Discrimination Scale

The Coping with Discrimination Scale (Wei et al, 2010) uses a 6 point-Likert scale. This

scale explores numerous ways in which people of color cope with racial discrimination. The

subscale used in this study consisted of educational advocacy, whose items reflected efforts to deal

with discrimination through educational or advocacy efforts at individual and societal levels. This

scale was used to assess how African American college students cope with racial

microaggressions.

Basic Psychological Needs at College Scale

The Basic Psychological Needs at College Scale (Brien, Forest, Mageau, Boudrias,

Desrumaux, Brunet, & Morin, 2012; Deci, Ryan, Gagné, Leone, Usunov, & Kornazheva, 2001;

Deci & Ryan, 2000) (adapted from was adapted from Basic Psychological Needs at Work Scale)

consists of 3 subscales featuring a 7-point Likert format. The 3 subscales were autonomy,

competence, and belonging. The belonging subscale was used to examine the African American

students’ feelings of belonging at college within the PWI context.

Data Collection Procedures

Participants were recruited anonymously via a Qualtrics survey link (online survey

software), social media (Facebook), and academic listservs. Participants were invited via an email

format message based on a convenience sampling strategy. Participants were asked during the

survey to reflect on: (a) their experiences with racial microaggression in the last 6 months, (b) ways

they have coped with racial discrimination at school, (c) the extent of which they identify as a

member of the African American community, and (d) their thoughts and feeling about their college

19

Data Analysis

The data was analyzed using SPSS and STATA. I began by conducting descriptive statistics.

Next, I conducted Pearson correlations. Last, I conducted T-tests and hierarchical regressions

including mediation and moderation analyses to explore my research questions. These procedures

20

CHAPTER III Results

Preliminary Analysis

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for all variables are presented in Table 2.

For preliminary analyses, I descriptive statistics offer further depth and descriptions of the study’s

sample.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for College Racial Microaggressions Data Set

Measures M SD α 1 2 3 4 5 6

1 Microinsults 3.10 1.32 .89 -

2 Microinvalidations 3.59 1.49 .89 .51*** -

3 Educational/ Advocacy

3.86 1.51 .87 .31** .32** -

4 Private Regard 5.64 .81 .86 .04 .03 .43*** -

5 Public Regard 3.57 .97 .78 -.24* .27** -.21* .10 -

6 Belonging 4.94 1.32 .82 -.07 -.03 .09 .39*** .17 -

Note: N = 97. *p <. 05. **p < . 01. ***p < . 001.SD, Standard Deviation.

Main Analysis: First Goal

To explore my first goal on how experiencing racial microaggressions (i.e. microinsults

and Microinvalidations) impacts African American college students’ sense of belonging on PWI

campuses within the college context, I hypothesized that groups (e.g. Undergraduate vs Graduate

Students) experience microinsults and microinvalidations differently and they impact these

students’ sense of belonging. I conducted multiple independent sample t-test to compare the

21

Research Question 1

I predicted that African American undergraduates experienced more microinsults than

African American graduate students. To test this prediction, I conducted a series of one-tailed,

independent sample t-test. Results did not support this prediction. Undergraduates students (M =

3.12, SD = 1.26) reported comparable experiences with microinsults than graduate students (M =

3.13, SD = 1.43) but not statistically significantly so, t (95) = -0.05, p > .05, one-tailed, mean

difference = 0.45. Error bars in Figure 2 (see Appendix) are 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2. Mean scores of microinsult experiences for undergraduate and graduate African

American students.

I predicted that African American undergraduates experienced more microinvalidations

than African American graduate students. To test this prediction, I conducted a series of one-tailed,

independent sample t-test. Results did not support this prediction. Undergraduates students (M =

22

3.33 , SD = 1.45) but not statistically significantly so, t (94) = 1.45, p > .05 (p = .07), one-tailed,

mean difference = 0.45. Error bars in Figure 3 (see Appendix) are 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3. Mean scores of microinvalidations experiences for undergraduate and graduate

African American students.

Main Analysis: Second Goal

To explore my second goal on how African American college students’ sense of racial

identity and coping strategies influenced the relationship between experiencing racial

microaggressions and sense of belonging on PWI campuses. I predicted that students’ racial

identity served as a moderator and educational advocacy as a coping strategy served as a mediator

for the relationship between racial microaggressions and students’ sense of belonging. I conducted

hierarchical regressions to test the moderation model and mediation model to address my goal and

my following research questions. To avoid potentially problematic high multicollinearity with the

interaction term, the variables were centered and an interaction terms between microinvalidations

23

Research Question 2

Public Regard Model

To test the hypothesis that African American college students’ sense of belonging is a

function of multiple factors. More specifically, I tested whether African American college

students’ sense of public regard moderated the relationship between microinvalidation experiences

and sense of belonging. I utilized a hierarchical regression to test this prediction. Step 1 of the

model included microinvalidation experiences. Step 2 of the model examined public regard, while

Step 3 of the model included the main effect of the interaction of public regard by

microinvalidation experiences. The final hierarchical regression model included microinvalidation

experiences, public regard, and interaction between microinvalidation and public regard.

The final model (F(3, 92) = 0.91, p > .05) accounted for 3% of the variance of predicting

students’ sense of belonging (R2 =0%). The final model included racial microaggression

experiences (β = -.07, p >.05), public regard (β = -.07, p <.001), and the interaction term (i.e. racial

microaggressions by public regard) (β = -.07, p >.05), but had no significant main effect. These

findings did not support my prediction that the relationship between African American college

students’ sense of belonging and racial microaggression experiences are moderated by public

24

Table 3

Hierarchical Regression Model Predicting Sense of Belonging as a function of Public Regard

Variable β SE β t Adj.

R2

Step 1 (F(1,94) = 0.08, p = 0.7835)

Microinvalidations -.03 -.03 -.28 .00

Step 2 (ΔF(1,91) = 8.39, p<.001, R2 =.16)

Microinvalidations .02 .02 .19

Public Regard .23 .17 1.63 .15

Step 3 (ΔF(1,90) = 7.41, p <.05, R2 =.20)

Microinvalidations .019 .02 .19

Public Regard .23 .17 1.61

Public Regard by Microinvalidations -.02 -.02 -.22 .04

(n=96). *p <. 05. **p < . 01. ***p < . 001.

Private Regard Model

I predicted that African American college students’ sense of belonging is a function of

multiple factors; more specifically whether students’ sense of private regard moderates the

relationship between experiencing microinvalidation and sense of belonging. I conducted a

hierarchical multiple regression analysis to test this prediction. The Step 1 model included

microinvalidation experience, while the Step 2 model examined private regard. The Step 3 model

investigated the interactions of students’ sense of private regard by microinvalidation experiences.

The final hierarchical regression model included microinvalidation experiences, private regard,

and interaction between microinvalidation and private regard.

Based on significant changes in the F statistic, the final model (F(3, 90) = 7.41, p < .01)

included both the main effects and the interaction terms (i.e. Step 3). This final model accounted

for 20% of the total variance in students’ sense of belonging (R2 =17%). The final significant main

effects included private regard (β = -.07, p <.001) and the interaction term (e.g. racial

25

experiences (β = -.07, p >.05). These findings supported my prediction that African American

college students’ sense of belonging is moderated by their sense of private regard (See Table 4).

Table 4

Hierarchical Regression Model Predicting Sense of Belonging as a function of Private Regard

Variable β SE β t Adj.

R2

Step 1 (F(1,94) = 0.08, p = 0.78)

Microinvalidations -.03 -.03 -.28 .00

Step 2 (ΔF(1,91) = 8.39, p<.001, R2 =.16)

Microinvalidations -.05 -.06 -0.58

Private Regard .65 .39 4.08*** .15

Step 3 (ΔF(1,90) = 7.41, p <.05, R2 =.20)

Microinvalidations -.08 -.09 -0.94

Private Regard .61 .37 3.88***

Private Regard by Microinvalidations .31 .21 2.18* .04

(n=96). *p <. 05. **p < . 01. ***p < . 001.

Figure 4. Interaction of private regard by microinsults experiences in predicting self-

26

Research Question 3

I hypothesized that educational advocacy as a coping strategy would mediate the

relationship between microinsults and sense of belonging. Baron and Kenny (1986) asserted

evidence for mediation is found under the following conditions: (1) the independent variable

(microinsults) significantly predicts the outcome variable (belonging), (2) the independent variable

(microinsults) significantly predicts the mediator variable (educational advocacy), and (3) the

mediator significantly predicts the outcome variable, while the independent variable (microinsults)

simultaneously no longer predicts the outcome variable. In regression model 1, microinsults did

not significantly predict belonging. Regression model 2, microinsults significantly predicted

educational advocacy. In the final regression model 3, I used microinsults and educational

advocacy as predictors of belonging. However, both microinsults and educational advocacy did

not significantly predict students’ sense of belonging (See Figure 4).

27

Main Analysis: Third Goal

To explore my final goal of exploring the effects of microinsults, sense of racial identity,

and coping strategies on an African American students’ sense of belonging within a PWI context,

I conducted a hierarchical regression.

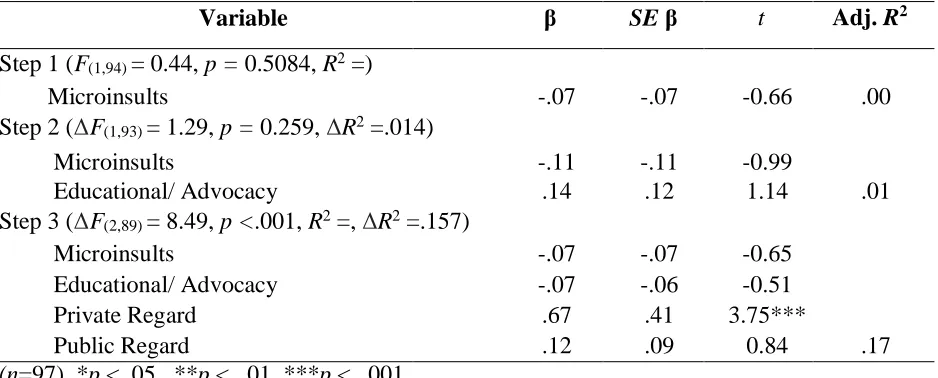

Research Question 4

To address my final goal, a hierarchical regression was utilized to explore predictors

associated with African American college students’ sense of belonging. The predictors are

continuous and were mean centered. The Step 1 model included racial microaggression

experiences. The Step 2 model examined educational advocacy as a main effect, and the Step 3

model examined the remaining main effects of racial identity (e.g. private and public regard).

Based on significant changes in the F statistic, the final model had an Adjusted R2 = 0.14, F(4,89)

= 4.74, p < 0.01. The final model accounted for 18% of the total variance in predicting sense of

belonging (Adjusted R2 = 0.14). The final significant main effect included private regard (β =.67,

p <.001) but not public regard (β =.12, p >.05), educational/ advocacy (β = -.07, p >.05), or racial

microaggression experiences (β = -.07, p >.05). These findings indicate African American college

students’ sense of racial identity, specifically private regard, is positively associated with

28

Table 5

Hierarchical Regression Model for Students’ Sense of Belonging

Variable β SE β t Adj. R2

Step 1 (F(1,94) = 0.44, p = 0.5084, R2 =)

Microinsults -.07 -.07 -0.66 .00

Step 2 (ΔF(1,93) = 1.29, p = 0.259, ΔR2 =.014)

Microinsults -.11 -.11 -0.99

Educational/ Advocacy .14 .12 1.14 .01

Step 3 (ΔF(2,89) = 8.49, p <.001, R2 =, ΔR2 =.157)

Microinsults -.07 -.07 -0.65

Educational/ Advocacy -.07 -.06 -0.51

Private Regard .67 .41 3.75***

Public Regard .12 .09 0.84 .17

29

CHAPTER IV Discussion

The primary goal of this research project was to better understand African American

college students experience racial microaggressions within the PWI context. The findings

supported and added to the existing literature on African American college students’ experiences

with racial microaggressions and its impact on these students’ sense of belonging. The African

American college students who participated in the study reported experiencing both microinsults

and microinvalidations on their respective PWI campus. The sample of students reported negative

effects of experiencing racial microaggressions and its impact on the sense of belonging to their

university.

African American college students from different academic standings reported different

amount of racial microaggression experiences. African American undergraduate and graduate

students reported experiencing racial microaggressions often. Both, graduate and undergraduates,

reported experiencing both microinsults and microinvalidations occasionally on campus. This

finding adds to the literature by exploring the potential difference in racial microaggression

experiences of African American undergraduates and graduates students. Overall, these

microinsults and microinvalidations made African American college students feel isolated and

unsupported on their restive university campuses.

Additionally, findings indicated some dimensions of racial identity can serve as a

protective factor moderating the relationship between microinvalidations and sense of belonging.

Specifically as hypothesized, sense of private regard buffered the effects microinvalidations have

on African American college students’ sense of belonging. This finding lends support to previous

30

when experiencing racism (e.g. Cross, 1998; Chavous et al., 2008; Sellers et al., 2003). In addition,

this result extends previous literature by suggesting private regard, specifically, can serve as a

protective factor when experiencing racial microaggressions within PWI college campus settings.

Moreover, the relationship between microinvalidations and belonging for African American

college students was not buffered by sense of public regard. This finding is noteworthy due to the

wealth of literature supporting that public regard serves as a protective factor when facing racially

charged situations (Chavous et al., 2008; Oyserman et al., 2001; Sellers et al., 2003; Sellers,

Copeland-Linder, Martin, & Lewis, 2006; Wong et al., 2003). Together, these findings illustrate

African American students’ racial pride (e.g. private regard) can serve as a protective factor.

However, while low public regard serves as a protective factor against racial discrimination for

African Americans, racial microaggressions may not be influenced by students’ beliefs of other

evaluative judgements of African Americans (e.g. public regard).

The results indicated that the coping strategy of education/advocacy did not mediate the

relationship between racial microaggressions and sense of belonging. However, this finding did

report some noteworthy results. First, this finding furthers previous literature on adaptive coping

strategies when experiencing racism for African Americans within the education setting. Results

revealed the adaptive coping strategy (e.g. educational advocacy) was not a mediator of the

relationship between African American students’ microinsults experiences and sense of belonging.

Previous literature has highlighted that adaptive coping strategies, in comparison to maladaptive

coping strategies (e.g. internalization), have positive outcomes for African Americans when

experiencing racism (Mellor, 2004). Consequently, findings show that within the educational

31

The findings exploring the effects of racial microaggression experiences, sense of racial

identity, and adaptive coping strategies on African American students’ sense of belonging reported

meaningful findings. Results revealed that students’ sense of private regard was a predictor of sense

of belonging. This finding has practical implications for African Americans and other students of

color on PWI campuses experiencing racism indicating that racial pride is key to belonging at their

respective universities.

Implications

The results of the study showed that African American students experience racial

microaggressions on a daily basis within college context. Consequently, experiencing racial

microaggressions showed negative effects on African American students’ sense of belonging at

their respected university. Furthermore, results showed that African American students that

reported higher sense of private regard and electing to educate and advocate the aggressor when

experiencing a racial microaggression had a lower sense of belonging.

Greater efforts should be taken to educate faculty and staff of PWI universities on the

importance of making all students feel welcome and included in the classroom and on campus,

overall. I recommend that universities mandate yearly diversity trainings to educate all faculty and

staff on racial microaggressions and other forms of racial discrimination on campus. Moreover,

teaching of racial microaggressions and other forms of racial discrimination should be included in

curriculum across disciplines. Current programs and safe spaces are examples of university led

programs that successfully increase inclusion of diverse students (Brenzinski et al, 2018).

Furthermore, faculty and staff members need to be aware of their own personal biases and possible

racial microaggressions that they may be unintentionally communicating to African American

32

and breakdown their personal biases to decrease the amount of racial microaggressions African

American students experience. The importance of social support to psychological and academic

performance and motivation have been well documented (Powell & Arriola, 2003; DeBerard et

al., 2004; Dennis, Phinney, & Chuateco, 2005). In addition, social support (e.g. mentorship

programs, academic networks, and safe spaces) plays a vital role in connecting African American

students with resources and support for coping with racial microaggressions which is necessary

for the academic survival of African Americans, particularly at PWIs.

Limitations and Future Directions

Caution is warranted when interpreting these findings. First, the study’s survey only

yielded a 49% response rate. Therefore, response bias is a potential limitation, where it is unclear

how well it represents the larger population of African American students at PWIs. Secondly, even

though we found significant differences between groups (e.g. Undergraduates vs. Graduates) it is

unclear due to the sample size of each sample group how well the study represents the overall

African American college student population at PWIs. Thirdly, the gender imbalance in the study

is also a limitation due to the high percentage of African American women that participated in the

study compared to African American men. Moreover, more research needs to examine gender

differences in experiencing racial microaggressions. African American females often perceived

double bias (i.e. racial and gender) within PWI college contexts (Alexander & Hermann, 2016).

Still, it was important to include both men and women in the analysis, despite the low number of

male participants in the study. Lastly, the racial composition of the predominantly white

institutions may cause some limitations to the analysis. College campus are becoming more and

more diverse with increasing enrollment of African American and other students of color

33

institution at which White students make up for 50 percent of more of the student body (Brown &

Dancy, 2009), the recent increase in students of color on campus can create more variation in racial

demographics on PWI campuses.

Conclusions

The challenges African American students face on predominantly White campuses, such

as institutional racism, inequitable treatment from faculty and university administrators, racial

discrimination, and negative stigma, are well document throughout the literature and contribute to

racial disparities in educational outcomes at the postsecondary level. Better understanding how to

support African American students’ experiencing of racial microaggressions and retain these

students in institutions of higher education is imperative. Consequently, campus climate is

frequently identified as contributing to educational and social inequalities (e.g. retention and

graduation rates, sense of belonging, and social integration) which translate to racial barriers (e.g.

racial microaggressions) for African American students. More clearly understanding the

experience of racial microaggressions and its impact may better equip faculty, administrators, and

counselors to support and retain African American students in higher education.

This study furthers the literature into African American college students’ experiencing

racial microaggressions. The current study identified racial identity (e.g. private regard) as a

potential protective factor. Moreover, this line of research has implications for innovations in

practice, counseling practices on college campuses, and diversity training for students and faculty

on such campuses. Therefore, I recommend future research that includes longitudinal studies

analyzing the experience of racial microaggressions throughout the different college populations

(e.g. undergraduate and graduate) to explore the connections between racial microaggressions,

34

REFERENCES

Aiken, L.S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Alexander, Q. R., & Hermann, M. A. (2016). African-American women’s experiences in graduate

science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education at a predominantly white

university: A qualitative investigation. Journal Of Diversity In Higher Education, 9(4),

307-322. doi:10.1037/a0039705

Allen, W. R. (1992). The color of success: African American college students outcomes at

predominantly White and historically Black public colleges and universities. Harvard

Educational Review, 62, 26-44.

Allen, W. R., Epps, E. G., & Haniff, N. Z. (Eds.). (1991). College in Black and White: African

American students in predominantly White and historically Black public universities.

Albany: State University of New York Press.

Anderson, L. P. (1991). Acculturative stress: A theory of relevance to Black Americans. Clinical

Psychology Review, 11, 685-702.

Ancis, J. R., Sedlacek, W. E. and Mohr, J. J. (2000), Student Perceptions of Campus Cultural

Climate by Race. Journal of Counseling & Development, 78: 180-185. doi:10.1002/j.1556-

6676.2000.tb02576.x

Astin, A. (1982). Minorities in American higher education. San Francisco: Josey-Bass.

Baber, L. D. (2012). A qualitative inquiry on the multidimensional racial development among first-

year African American college students attending a predominantly White institution. The

35

Baumeister, R. F. & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments

as a fundamental human motivation. Psychology Bulletin, 117, 497-529.

Booker, K. C. (2006). School belonging and the African American Adolescent: What do we know

and where should we go? The High School Journal, 89, 1-7.

Branscombe, N., Schmitt, M., & Harvey, R. (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among

African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-bring. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 135-149.

Brezinski, K., Laux, J., Roseman, C., O’Hara, C., & Gore, S., (2018) "Undergraduate African–

American student’s experience of racial microaggressions on a primarily white campus",

Journal for Multicultural Education, Vol. 12 Issue: 3, pp.267-277,

https://doi.org/10.1108/JME-06-2017-0035

Brien, M., Forest, J., Mageau, G. A., Boudrias, J., Desrumaux, P., Brunet, L., & Morin, E. M.

(2012). The Basic Psychological Needs at Work Scale: Measurement invariance between

Canada and France. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 4(2), 167–187.

https://doi-org.proxy.lib.duke.edu/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2012.01067.x

Brondolo, E., ver Halen, N., Pencille, M., Beatty, D., & Contrada, R. (2009). Coping with racism:

A selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. Journal

of Behavioral Medicine, 32, 64-88.

Brown, C.M. and Dancy, E.T. (2009). “Predominantly white institutions”, Encyclopedia of

American Education, Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA, Vol. 1, pp. 523-526

Cabrera, N. L. (2014). Exposing Whiteness in higher education: White male college students

minimizing racism, claiming victimization, and recreating White supremacy. Race

36

Caldwell, C. H., Sellers, R. M., Bernat, D. H., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2004). Racial identity,

parental support, and alcohol use in a sample of academically at-risk African American

high school students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 34, 71-82. Doi:

10.1023/B:AJCP.0000040147.69287.f7

Carroll, G. (1998). Environmental stress and African Americans: The other side of the moon.

Westport, CT: Greenwood. Press.

Chavous, T. M. (2005). An intergroup contact-theory framework for evaluating racial climate on

predominantly white college campuses. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36,

239 –257. doi:10.1007/s10464-005-8623-1

Chavous, T.M., Bernat, D., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Caldwell, C., Kohn-Wood, L.P., & Zimmerman,

M. (2003). Racial identity and academic attainment among African American adolescents.

Child Development, 74(4), 1076-1091.

Chavous, T.M., Rivas-Drake, D., Smalls, C., Griffin, T., & Cogburn, C. (2008). Gender matters

too: School-based racial discrimination experiences and racial identity as predictors of

academic adjustment among African American adolescents. Developmental Psychology,

44(3), 637-654.

Cohen, G., L., & Garcia, J. (2008). Identity, belonging, and achievement: A model, interventions,

implications. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, 365-369.

do:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00607.x

Compas, B.E., Connor, J. I., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping

with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress and potential in theory