1

FARMSCAPING:HEDGEROWAND ROADSIDE

PLANTINGS

FOR BIOINTENSIVE PEST MANAGEMENT

Robert L.

Bugg

InformationGroup

Sustainable

Agriculture Research

and

Education Program

University

of

California

Davis,

CA 95616-8533

John

H.

Anderson

Yolo

County

Resource

Conservation

District

221 West Court StreetNo. 5

ABSTRACT

Farmscaping is the conscious and integrated modificationof agricultural settings,em¬

phasizing management of field margins,hedgerows, windbreaks, and specific vegetation planted along roadsides, ditches, and adjoiningwildlands. The ultimate aim of farmscaping is

toachieve moresustainable farmingsystems. Biologically-intensiveorbiointensive pestman¬

agementrelies primarilyonbiological and cultural controls and host plant resistance. Taken together, these could be thoughtof as "agroecosystem resistance" to pests. Hedgerows and

otherborderplantings can have important impacts on biointensive integrated pest manage¬

ment;properly designed and managed hedgerows and vegetationally-diverse field borders can

assist inboth biological and cultural control of arthropod pests of agriculture. Untilnow, the bulk of the researchonthissubject has been conductedinEngland andEurope. Most priorstudies

sufferfrom lackoftruereplication and insufficient spatial scale. Moreover, in the vastmajor¬

ity ofcases, the hedgerows employed have notbeenplanned with arthropods in mind. Based

on ourmany yearsof practical and research experience, we have developed a design fora

bio-diversehedgerow comprising native and introduced shrubs, perennialgrasses,and herbaceous perennial and annual broadleafplants known to attract and sustain beneficial arthropods and other desirable wildlife. The estimated costof establishment per 1/2-mile strip is $1,378.00.

Roadside plantings ofnative perennialgrasses and associatedspecies have been usedin Iowa and other midwesternstates tosuppress weeds, reduce the need for herbiciding and other

maintenance tools, and restore wildlife. In California, conventional managementof agricul¬

tural roadsides leads todominationby noxious weeds. Availability of seed forvarious native grasses is increasing,asis public interest in their restoration. Agricultural roadsides typically contain severaltopographiczones orniches withvaryingenvironmental conditionsand man¬

agementrequirements. Growth form, height, and environmentaloptima and tolerances of the various speciesdictate the niches towhich theymaybe assigned. Complexes ofnativegrasses

can be established using either herbicide-intensive ornon-herbicidal techniques, which are summarized here. Once the grasses areestablished, herbicidesareseldomneeded.

Farmscaping is the conscious and integrated modification ofagricultural settings, em¬

phasizing management of field margins, hedgerows, windbreaks, and specific vegetation

planted alongroadsides, ditches,and adjoining wildlands. Theproximal goals of farmscaping

maybe toprovidehabitat for wildlife, enhance the esthetics of the farm, provide natural

weed controlthrough competition, andestablish arthropod pestcontrol through enhancement

of naturalenemyactivity. Plants maybeemployed that have specialentomological associa¬ tions. The ultimate aim of farmscaping is to achieve more sustainable farming systems. Biointensive pest managementrelies primarilyon biological and cultural controlsand host plant resistance (Frisbie and Smith, 1989). Taken together, these could be thought of as

"agroecosystem resistance" topests. Hedgerows and other border plantings canhave important impacts on biointensive integrated pest management; properly designed and managed hedgerows and vegetationally-diverse field borders canassist inbothbiological and cultural

control ofarthropod pestsof agriculture. Until now,the bulk ofthe research onthis subject has

been conducted inEngland and Europe. Mostpriorstudies suffer fromlackoftruereplication and insufficientspatial scale. Moreover, inthe vast majority ofcases, the hedgerows employed havenotbeen planned with arthropods inmind. Based on our manyyears of practical and re¬ searchexperience,we havedeveloped a design fora biodiverse hedgerow comprising native andintroducedshrubs, perennialgrasses,and herbaceousperennial and annualbroadleafplants knownto attractand sustainbeneficial arthropods and otherdesirable wildlife.

Roadside plantings of native perennialgrassesand associated species havebeen used in

Iowaand othermidwesternstates tosuppress weeds, reduce the need forherbiciding and other

maintenance tools, and restore wildlife. InCalifornia, conventional managementof agricul¬ turalroadsidesleadstodominationby noxious weeds. Availability ofseed for various native grassesis increasing, as is public interest intheir restoration. Agricultural roadsides typically contain several topographic zones or nicheswith varyingenvironmental conditions and man¬

agementrequirements. Growth form, height, and environmental optima and tolerances of the variousspeciesdictate the niches towhichtheymaybe assigned. Complexes of nativegrasses

canbeestablished using either herbicide-intensive or non-herbicidal techniques, which are

summarized here. Once the grasses areestablished, herbicidesareseldom needed.

Here we will discuss the theory and practiceofhedgerow and roadside plantings in California.

Hedgerows

Thegoldenageof windbreaks in theUrdted States occurred during the 1930s and 1940s,

when, to staveoff wind erosionoftopsoil, the U.S.D.A. Soil Conservation Service (S.C.S.) su¬

pervised the planting of thousands of acres in shelterbelts throughout the Midwest (Van

Eimern, 1967). Yet the broad and tall windbreaks planted by the S.C.S. are merely hedgerows

ofspecial types. The tradition of fostering hedgerows extendsmuch furtherback than the Dust

BowlDays. From time immemorial, hedgerows have played key roles in agriculture. In an¬ cient Europeand the British Isles, hedgerows comprising trees, shrubs,and perennial grasses demarcated propertylines, sheltered farmlands and dwellings from winds, and provided food (game animals, hazelnut, walnut, quince), fodder (acorns), and coppicingtree specieswere re¬

peatedly harvested for bothstructural and fuel wood (Pott, 1989). Moreover, research has re¬

peatedly shown thathedgerows and windbreakscan play importantroles in agriculturalpest

management, both negative and positive (see reviewsby Van Eimern, 1964, Van Emden, 1965, Altieri and Letourneau, 1982).

Perennialvegetation harborssomearthropods that donot venture much into surround¬

ingarable crops("hard-edgespecies" inthe usageof Duelli et al., 1990). For example, Bishop andRiechert (1990)showed that there were few species incommonbetweenthe spiderfauna of

vegetable gardens and that ofa nearby wooded area. Similar results were obtained by Maelfaitand De Keer(1990) in comparingthe spider faunaeof intensively-grazed pastureland and itsborderareas. On the other hand certain"soft-edge species" mayshow increased abun¬

dance inthe arable landsadjoining perennialvegetation,suchashedgerows. Therecanbeneg¬

On the negative side, hedgerows might includeplants thatserve as reservoirs

for

in¬ sect-borne viruses,or as overwintering sites for boll weevil (Slosseretal., 1984), and poplarsand cottonwoods{Populusspp.) arerequired alternatehost for variousrootaphids {Pemphigus

spp.) thatattack beets and lettuce (Davidsonand Lyon, 1986). In

South Africa,

windbreaks of

silky oak {Grevillea robusta)can predisposeforproblems with citrus

thrips

{Scirtothrips

au-rantii) (Grout and Richards, 1990). Windbreakscanalsopredispose forlocalinfestations

of

aphids (Homoptera: Aphididae) and thrips (Thysanoptera; Thripidae) because

the

winged

colonizingforms settle insheltered areas (Lewis,1965a, 1965b).

Onthe positiveside, hedgerowscan harbor importantbeneficial arthropods.

Much of

the relevantresearch has beendone in England and Germany. Ground beetles (Carabidae:Coleoptera)mayoccupyhedgerowsduring winter, thendisperseto adjoining

field

cropswith

the advent ofspring,aswassuggested forPlatynus dorsalts inanunreplicated study ofan inten¬ sively-run farm nearKiel, Germany (Knauerand Stachow, 1987). InEngland,

willows

{Salix

spp.) andanalder {Alnusglutinosa) canharbor predatory truebugs (Hemiptera:

Anthocoridae,

Miridae) that later disperse to orchards and attackcodling moth {Cydia pomonella) or pear

psylla {Psylla pyricola) (Solomon, 1981; Gangeand Llewellyn, 1989). Wind shelter (Lewis,

1965a;Pollard, 1971) and flowers(Bowdenand Dean, 1971) provided byhedgerows canbecru¬

cial to hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae) which attack aphid pests ofcrops. Nectarsources in hedgerows arealso importantto parasiticwasps (Van Emden, 1962). In California, perennial

grasses (whichcanbecontained in hedgerows)canprovide sitesforaestival-hibernal diapause

by convergentlady beetle {Hippodamia convergens, Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) (Hagen, 1962,

1974). In South Africa, facultatively-pollinivorous predatory mites {Euseius addoensis a

d-doensis) can be particularlyabundant in citrus (Citrus sinensis) sheltered bywindbreaks of pollen-producing Montereypine (Pinus radiata) (Grout and Richards, 1990). Anagrus epos, a

key parasite ofgrape leafhopper (Erythroneura elegantula) and westerngrape leafhopper

(Erythroneura variabilis) can be harbored onoverwintering eggs of leafhoppers that infest

and Nakata, 1965, 1973) orcultivated plants (e.g., prune leafhopper, Edwardsiana prunicola,

onFrench prunes[Kidoetal., 1984, Pickettetal., 1990]). Frenchprunes are now being planted

alongside Californiavineyardsto enhancebiological control.

Relatively few of thedust-bowl-erashelterbelts and the prehistoric hedgerows re¬ main,duetothe push in the U.S. andin Europe during the 1960s and 70sto plantarablecrops

fencerowtofencerow inorderto"feed the world." Moreover,the trend towards "cleanfarming"

hasentailed indiscriminate herbicidingordisking ofnon-croppedground in ordertoavoidweed

problems. These agriculturaltrendshave led to a greatloss of wild, and often native, vegeta¬ tion thatonce persisted in roadsides and along sloughs. As a result, biodiversity has been

greatly reducedon farmlands. The erosionof foreign markets hassomewhatlessened the col¬

lectiveurge to farm marginal lands, and there is increased awareness of the need topreserve and restore native vegetationand wildlife habitat.

Hedgerows, those valuable and venerable features of the farmscape, can makea major

contributiontowardsimproving this situation. Thishasbeen clearly shownby 10yearsofexpe¬

rienceat Hedgerow Farms (owned byJ.H. Anderson). This site nearWinters, Yolo County,

California) features roadside and hedgerow plantings that bya conservative estimate com¬

prise 14 native and 9 introduced speciesof native perennialgrasses, 9 native and 6 introduced

genera of shrubs, and 6 nativeand 5introduced treespecies. Many ofthese plants have

clear

as¬sociations withbeneficial insects and otherdesirable wildlife. Eighty-eightspecies of birds

have been observed atthe site(Table 1), reflecting the richnessof the habitats provided. We believethat the knowledge developedat HedgerowFarms can now be applied in designing

multispecies hedgerows to attractbeneficial insectsand otherdesirable wildlife, and topro¬ mote biologically-intensiveintegrated pestmanagement.

Californiaagriculture has longused both exoticand native trees for windbreaks, inar¬ eas where windsare a persistentproblem. Coastal and desert areas have especially benefited fromwind shelterprovided by Arizona cypress {Cupressusglabra), athel {Tamarix aphylla), blue gum{Eucalyptusglobulus), Lombardy poplar(Populusnigi-avar. italica), Montereycypress

{Cupressus macrocarpa), and Siberian elm (Ulmus pumila). However, these species wereusu¬

allyemployed in single-species windbreaks, and without regard to their value (or lack thereof) tobeneficial arthropodsor otherdesirable wildlife. These facts have almost cer¬

tainly lessenedanypositive contribution that these windbreaks could have made to biologi¬ cally-intensive integratedpestmanagement. Basedonourlong experience and ourreviewof the

relevantliterature, we conclude thathedgerow and windbreak compositioncanbe improved

and diversified, withaneye to enhancing activityby beneficial arthropods. Anancillary ben¬ efit will beprovision of habitat fora diversity of desirable wildlife species, including am¬ phibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. Therural landscape will be beautified through addi¬ tionof esthetically-pleasing nativegrasses and shrubs. Webelieve that by such approaches, restorationecology and production agriculturecan dovetail.

Hedgerow Designand Implementation

Ourobjective is toestablish multispecies hedgerows to enhance biological controland desirable wildlifespecies, through provision of shelter, overwinteringhabitat, nesting sites, and food.

Hedgerow Species Composition

Weare testingnew hedgerow designs. Wind isnota majorproblem in Yolo County,so we focus mainlyonshrubs, perennial grasses, and herbaceous perennials and annuals, rather

thanon trees,so as to minimize the shading of adjacent farmlands. Weemphasize a rangeof

native Californianshrubs easilygrownin Yolo County, and knownto attract largenumbers of beneficial insects: blue elderberry {Sambucus caerulea), coyote brush (Baccharis pilularis) (Kido et al., 1981; Bugg and Heidler, 1981), California coffeeberry {Rhatnnus californica),

California lilacs {Ceanothus spp.) (Bugg and Heidler, 1981), California wild buckwheat

{Eriogonum fasciculatum) (Swisher, 1979), holly-leaved cherry (Prunus ilicifolia), toyon

{Heteromeles arbutifolia), and various native willows {Salix spp.). Wealso use exotic species

known forentomological associations: soapbarktree {Quillaja saponaria) (Bugg, 1987), sweet fennel {Foeniculum vulgarevar.dulce) (Maingayetal., 1991), and toothpickammi {Ammi

vis-naga)(Buggand Wilson,1989). See Appendix 1 fora discussionof beneficial

insect/plant

asso¬ciations thatwehave observed. Outofconcern forother wildlife, weinclude the low-mainte¬ nancefruit-producingpersimmon{Diospyroskaki) andpomegranate {Punica granatum), which arebothuseda sourcesof winter foodby native bird species. The understoriesof the hedgerows

will beassigned tomixtures ofnativeCalifornianperennialgrasses: bluewildrye{Elymus glau-cus), California brome {Bromuscarinatus),slenderwheatgrass {Agropyron trachycaulum var.

majus), creepingwildrye {Leymus triticoides), meadowbarley {Hordeum brachyanther um)

and

purpleneedle grass {Stipa pulchra). Our extensive experience shows that

several

of these

grasses haveexcellent seedling vigor, establish rapidly, and will thereaftersuppress

the

inva¬sive annual weeds that dominateconventionally-managed fencerowsandroadsides. Perennial grassesare well knownas the major siteforaestival-hibernal diapause

of

convergentlady bee¬

tle {Hippodamia convergens) (Hagen, 1962, 1974). Once the hedgerow isreasonably weed free,

we willestablish ablend ofinsectaryplants (Harmony Farm Supply, Sebastopol, California).

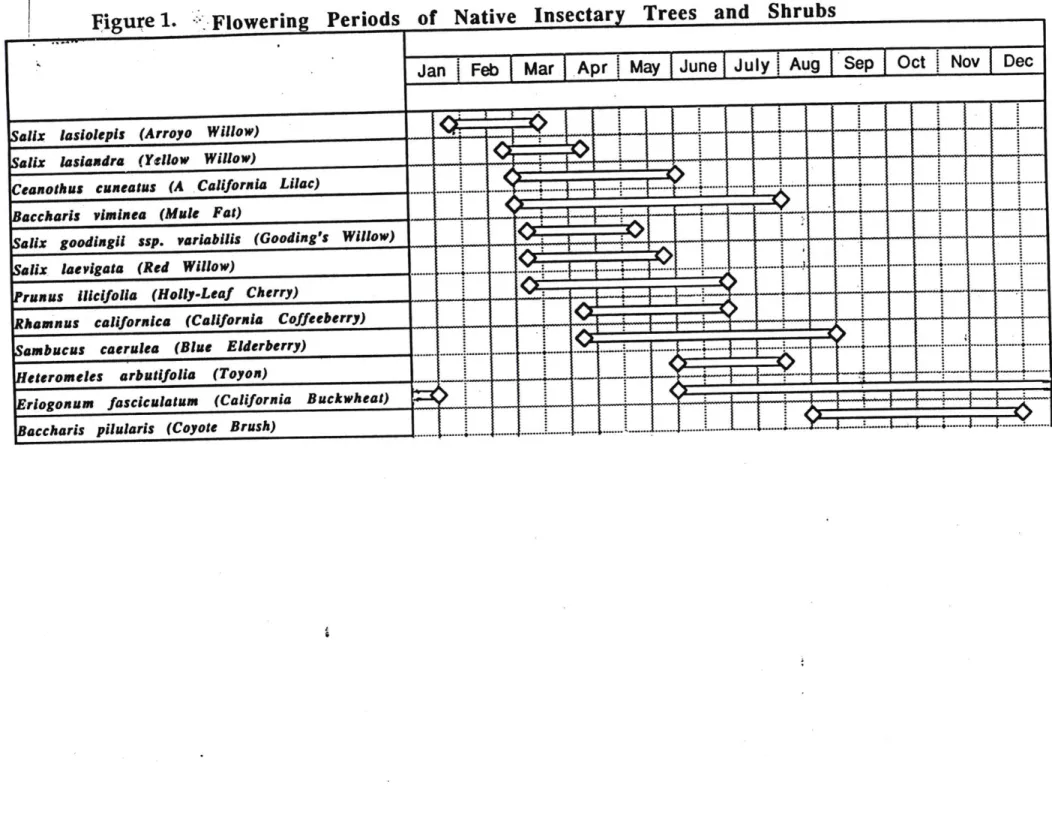

Together,the hedgerow plants would supplyaccessiblenectar, pollen, and alternate

hosts

and

prey through mostof theyear (see Figures 1 and 2,basedon our ownobservations

and

Munz,1973).

HedgerowDesign andImplementation

Ourapproach is tousestandard farming implements and practicesto

install hedgerow

shrubsamid stands of nativeperennialgrasses. Hedgerowswill be4.58m (180")wide, andwill

eachcomprise 3, 1.52-m (60") beds,separated by irrigation furrows.All beds

will be seeded

tonative grasses;thecentral bed will containshrubsas well. Seedof the

perennial

grasseswill

be

drilled to a depthof 1.27cmduring October. Theouteredgesofeach of theouterbeds will beseeded tocreepingwildrye, becauseourobservationsshow that itcanrecover

rapidly from

in¬advertent diskingorherbicide application. The remainder ofeachof the two outerbeds and the entire central bed will be seeded with appropriate mixesof the other species. Sections will

berandomlyassigned tomixturesofblue wildrye, California brome,meadow

barley, and

slen¬ derwheatgrass (by-weight 1:1:1:1 blend of seeds)orof meadowbarleyandpurple

needlegrass(1:1). Grass isseeded using a Truaxnativegrassseed drill. Shrubsand herbaceous

perennials

(1-year-old liners)will beplanted during NovemberthroughMarch into thecentral bed

amid

a matrixofperennialgrasses.After grasses areestablished (year 2) andweedsaresuppressed, astrip will be disked outand replaced with a seeded commercial insectary mixture, and native Lomatium spp., Perideridia spp.,Achillea borealis, andAsclepiasfascicularis.

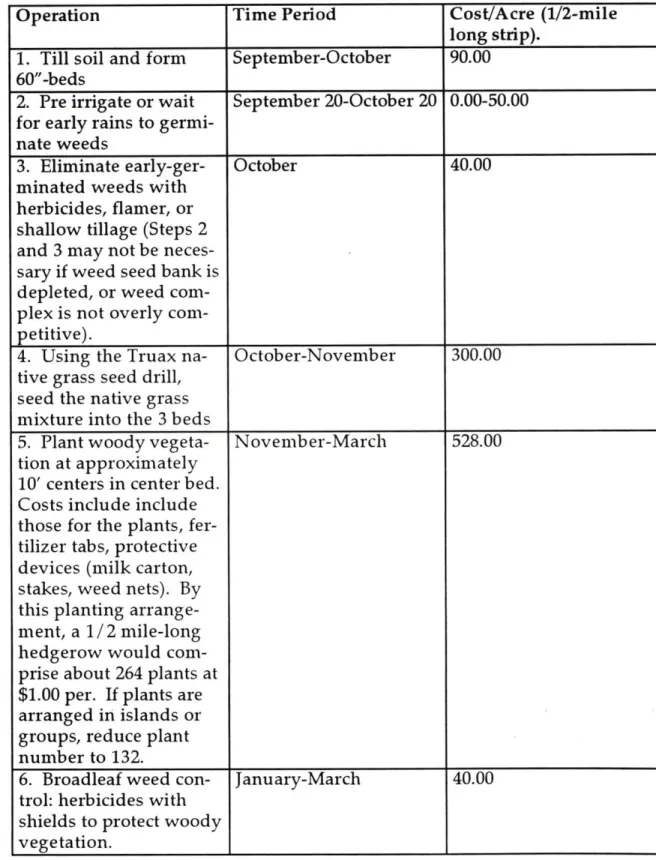

Theschedule ofoperationsand approximatecosts for hedgerowestablishmentare pre¬ sented inTable2. Theestimated costof establishment per1/2 -mile (0.8km) strip is $1,378.00.

Roadside Plantings

Roadsideplantings of native perennialgrasses andassociated species have been used in Iowa and othermidwesternstates tosuppress weeds, reduce the needfor herbiciding and other

maintenance tools, and restore wildlife. In California, conventional managementof agricul¬ tural roadsides leads to domination by invasive annual weeds, including wild oat {Avena

fatua), ripgutbrome {Bromus rigidus), and yellow starthistle (Ceiitaurea solstitialis).

Established stands of many native grasses can preemptcolonzation by these weeds. Availability of seed for various nativegrasses is increasing, as is public interest in their

restoration. Agricultural roadsides typically containseveral topographiczones orniches with

varyingenvironmental conditionsand managementrequirements. Growthform,height, and en¬

vironmental optima and tolerancesof the various species dictate the niches in which they are

suitable (Figure 3,adapted from Bugg etal., 1991). Complexes of nativegrasses canbe estab¬

lished using eitherherbicide-intensive ornon-herbicidal techniques, whicharesummarized in

Table 3 (adapted from Buggetal., 1992). Once thegrasses areestablished, herbicides aresel¬

Literature Cited

Altieri, M.A., and D.K. Letourneau. 1982. Vegetationmanagement andbiological control in

agroecosystems. Crop Protection1:405-430.

Bishop, L., and S.E. Riechert. 1990. Spidercolonizationofagroecosystems:Source and mode.

EnvironmentalEntomology 19:1738-1745.

Bowden, J. , and G.J.W. Dean. 1977. The distribution of flying insects in and near a tall

hedgerow. Journal ofApplied Ecology 14:343-354.

Bugg, R.L. 1987. Observations on insects associated with a nectar-bearing Chilean tree, Quillaja saponaria. Pan-Pacific Entomologist 63:60-64.

Bugg, R.L. 1990. Farmscaping with insectaryplants. Permaculture Activist6(2):1, 6-7.

Bugg,R.L. 1991. Farmscaping With InsectaryPlants. Sustainable Agriculture Research and

EducationProgram, UniversityofCalifornia, Davis. Mimeographed handout. 7pp. Bugg, R. L., D. Amme,J.H. Anderson, W.T. Lanini,andW.S.Halverson. 1992. Establishing na¬

tive perennial grasses in California. Sustainable Agriculture News (a newsletterof the University of California Sustainable AgricultureResearch and Education Program, Davis, Calif.)4 (3):In press.

Bugg,R.L., J.H. Anderson,J.W.Menke, K.Crompton, and W.T.Lanini. 1991.

Perennial

grassesas roadside covercrops to reduce agricultural weeds. Components (a newsletter of the

University of CaliforniaSustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program,

Davis,

Calif.) 2(1):14-16.

Bugg, R.L., and N.F.Heidler 1981. Pest Management with California Native

Landscape

Plants. University of California Appropriate Technology Program, Research Leaflet Series #8-78-28. 8 pp.Bugg,R.L.,and L.T. Wilson. 1989. Ammi visnaga (L.) Lamarck (Apiaceae): associated

benefi¬

cial insects and implications for biological control, with emphasis on the bell-pepper agroecosystem. Biological Agricultureand Horticulture6:241-268.Davidson, R.H.,and W.F. Lyon. 1987. Insectpests of farm, garden, and orchard. John Wiley

and Sons, NewYork, N.Y.

Doutt, R.L., and Nakata, J. 1965. Overwintering refuge of Anagrus epos (Hymenoptera:

Mymaridae). Journal ofEconomicEntomology 58:586.

Doutt,R.L., and Nakata, J. 1973. The Rubus leafhopperand its egg parasitoid:an endemic

bi-oticsystemuseful ingrapepestmanagement. EnvironmentalEntomology 2:381-386.

Duelli, P., Studer,M., Marchand, 1., and S.Jakob. 1990. Population movementsofarthropods betweennatural and cultivated areas. Biological Conservation54:193-207.

Frisbie, R.E., andJ.W. Smith, Jr. 1989. Biologically intensive integrated pestmanagement:The Future. Pp. 151-164 in: Menn, J. J., and A.L. Steinhauer, Editors. Progress and Perspectives

for the21stCentury. EntomologicalSociety of America, Centennial National Symposium. Entomological Society of America, Lanham, Maryland.

Gange, A.C.,and M. Llewelyn. 1989. Factors affecting colongisationby theblack-kneed capsid (Blepharidopterus angulatus (Hemiptera: Miridae) from alder windbreaks. Annals of Applied Biologyl14:221-230.

Grout, T.G.,and G.l. Richards. 1990. The influenceof windbreak species on citrus thrips (Thysanoptera:Thripidae) populations and theirdamage to SouthAfrican citrusorchards.

Journal of theEntomological Society of South Africa 53:151-157.

Hagen, K.S. 1962. Biology and ecology of predaceous Coccinellidae. Annual Review of Entomology7:289-326.

Hagen, K.S. 1974. The significanceof predaceous Coccinellidae inbiological and integrated controlofinsects. Entomophaga 7:25-44.

Kido, H., D.L. Flaherty, C.E. Kennett, N.F. McCalley, and D.F.Bosch. 1981. Seeking therea¬

sons fordifferences in orangetortrix infestations. California Agriculture 35(7,8): 27-28.

Kido, H., D.L. Flaherty, D.F. Bosch, and K.A. Valero. 1984. French prunetrees asoverwinter¬ ing sites for the grape leafhopper egg parasite. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 35:156-160.

Knauer, N., and U. Stachow. 1987. Activitaten vonLaufkafern (Carabidae Col.) in einem

in-tensiv wirtschaftendenAckerbaubetrieb - - ein Beitrag zur Agrarokosystemanalyse. Journal ofAgronomyand Crop Science 159:131-145.

Lewis, T. 1965a. Theeffectsof an artificial windbreakonthe aerial distribution of flying in¬

sects. Annals of Applied Biology55:503-512.

Lewis, T. 1965b. Theeffect ofanartificial windbreakonthedistribution ofaphids ina lettuce crop. Annals of Applied Biology55:513-518.

Maelfait, J.-P.,and R. De Keer. 1990. The borderzoneofanintensively grazed pastureasa cor¬ ridor forspiders Araneae. Biological Conservation 54:223-238.

Maingay, H., R.L. Bugg, R.W. Carlson, and N.A. Davidson. 1991. Predatory and parasitic

wasps(Hymenoptera) feeding at flowersofsweetfennel {Foeniculutn vulgare Miller var.

dulce Battandier &: Trabut, Apiaceae) and spearmint {Mentha spicataL., Lamiaceae) in

Massachusetts. Biological Agriculture and Horticulture 7:363-383.

Munz, P.A. (in collaboration with D. D. Keck). 1973. A California Flora and Supplement. Universityof California Press,Berkeley.

Pickett, C.H., L.T. Wilson,and D.L.Flaherty. 1990. Theroleof refuges incrop protection, with

reference toplantings ofFrenchprune trees inagrape agroecosystem. Chp. 10, pp. 151-165

in: N. J. Bostonian, L. T. Wilson, and T. J. Dennehy (eds.) Monitoring and Integrated Management ofArthropod Pests of Small Fruit Crops. InterceptLtd., Andover,Hampshire, England.

Pollard, E. 1971. Hedges. VI. Habitat diversityand crop pests: a study of Brcuicoryne

Frass/-cae and itssyrphid predators. Journal ofApplied Ecology8:751-780.

Pott, R. 1989. Historische und aktuelle Formen der Bewirtshaftung von Hecken in

Nordwestdeutschland. ForstwissenshaftlichesCentralblatt 108:111-112.

Slosser,J.E.; R.J. Fewin, J.R. Price, L.J. Meinke, and J.R. Bryson. 1984. Potential of shelterbelt

managementfor boll weevil (Coleoptera:Curculionidae) control in the Texasrolling plains.

Solomon, M.G. 1981. Windbreaks as a sourceof orchard pestsand predators. Pp. 273-283 in:

Thresh, J.M. (ed.)pests,pathogens and Vegetation. Pitman, London.

Swisher, R.G. 1979. ASurveyof the Insect FaunaonEriogonumfasciculatumin the San Gabriel

Mountains,Sauthern California. M.S. thesis. Dept. of Biology, Calif. State Univ., Los

Angeles.

Van Eimern, J. (Chairman). 1964. Windbreaks and Shelterbelts. World Meteorological AssociationTechnicalNoteNo.59. 188 pp.

Van Emden, H.F. 1962. Observations of the effectof flowers onthe activity of parasitic Hymenoptera. Entomologist's Monthly Magazine 98:265-270.

Van Emden, H.F. 1965. The role of uncultivated land in the biology ofcrop pestsandbeneficial insects. Scientific Horticulture 17:121-136.

Table 1. Birds observed at

Hedgerow Farms

(Yolo County

Roads

27

and

88,

be¬

tween Winters and

Esparto,

Yolo

County,

California) (R. Jones

and J.H.

Anderson,

personal

communications).

Order: Common Names

CICONIIFORMES: AMERICAN BITTERN, GREAT EGRET, SNOWY EGRET, GREEN

HERON, GREAT BLUEHERON

ANSERIFORMES:MALLARD, CINNAMON TEAL

FALCONIFORMES: TURKEY VULTURE, BLACK-SHOULDEREDKITE, NORTHERN

HARRIER, GOLDEN EAGLE, RED-TAILED HAWK, SWAINSON'S HAWK,

ROUGH-LEGGEDHAWK,AMERICANKESTREL, MERLIN, PRAIRIEFALCON

GALLIFORMES:RING-NECKEDPHEASANT, CALIFORNIA QUAIL

CHARADRIFORMES: KILLDEER, LONGBILLEDCURLEW

COLUMBIFORMES:MOURNINGDOVE, ROCK DOVE

STRIGIFORMES:GREAT HORNED OWL,COMMON BARN OWL, BURROWING OWL

APODIFORMES:ANNA'S HUMMINGBIRD, BLACK-CHINNEDHUMMINGBIRD,

PICCIFORMES: NORTHERN FLICKER, REDBREASTED SAPSUCKER, NUTTAL'S

WOODPECKER,DOWNY WOODPECKER, ACORN WOODPECKER

PASSERIFORMES:WESTERN KINGBIRD, ASH-THROATED FLYCATCHER, BLACK

PHOEBE, SAY'S PHOEBE, HORNED LARK, BARN SWALLOW, CLIFF SWALLOW,

NORTHERN ROUGH-WINGED SWALLOW, SCRUBJAY, YELLOW-BILLEDMAGPIE,

COMMON RAVEN, AMERICAN CROW, PLAIN TITMOUSE, BUSH-TIT,REDBREASTED

NUTHATCH, BEWICK'S WREN, HOUSE WREN, RUBY CROWNED KINGLET, HERMIT

THRUSH, SWAINSON'S THRUSH, AMERICAN ROBIN, WESTERN BLUEBIRD,

MOUNTAIN BLUEBIRD, NORTHERN MOCKINGBIRD, AMERICAN PIPIT, CEDAR

WAXWING, LOGGERHEADSHRIKE, EUROPEAN STARLING, WARBLING VIREO,

YELLOW-RUMPEDWARBLER, YELLOWWARBLER, WILSON'S WARBLER,

ORANGE-CROWNED WARBLER, BLACK-THROATED GREY WARBLER, TOWNSENDS

WARBLER, HERMITWARBLER, WESTERN TANAGER, BLACK-HEADED GROSBEAK, CALIFORNIA BROWN TOWHEE, RUFOUS-SIDEDTOWHEE, SAVANNAH SPARROW,

SONG SPARROW, DARK-EYEDJUNCO, WHITE-CROWNED SPARROW,

GOLDEN-CROWNED SPARROW, FOX SPARROW, WESTERN MEADOWLARK, RED-WINGED

BLACKBIRD, BREWER'S BLACKBIRD, BROWN-HEADED COWBIRD, NORTHERN

ORIOLE, AMERICAN GOLDFINCH, LESSER GOLDFINCH, HOUSE FINCH, PURPLE

Table 2. Establishmentschedule for

hedgerows.

Operation

Time Period Cost/Acre(1/2-mile

long strip).

1. Till soil and form 60"-beds

September-October

90.00 2. Preirrigate

orwait

for

early

rains

togermi¬

nate weedsSeptember

20-October 20

0.00-50.003. Eliminate

early-ger¬

minated weeds with

herbicides, flamer, or shallow

tillage

(Steps

2

and 3may not

be

neces¬sary

if weed

seed bank

is

depleted,

orweed

com¬plex is

notoverly

com¬petitive).

October 40.00

4.

Using the Truax

na¬ tive grassseed

drill,

seed the native grass mixture into the 3bedsOctober-November 300.00

5. Plant

woody

vegeta¬tion at

approximately

10' centers in centerbed.

Costs include include

those for the

plants, fer¬

tilizer tabs,

protective

devices (milkcarton,

stakes, weed nets).

By

this

planting

arrange¬ ment, a 1/2mile-long

hedgerow

would

com¬prise

about

264

plants

at $1.00 per.If plants

arearranged in islands

or groups,reduce

plant

number to 132.

November-March 528.00

6. Broadleaf weed con¬

trol; herbicides with shields toprotect

woody

vegetation.

7.

Vegetation

control

around individual

woody

plants.

February-May

40.008. Furrow

irrigation

every

2-4

weeks for

the

first year.

June-January

150.009. Summer spot

weed

control,

using

herbicide

or hoe.

June

-September

40.0010. Drill orbroadcast mixes offorb seeds into outerbeds:

toothpick

ammi, fennel yarrow,

blazing

star,bee

phacelia,

etc.September-October

100.001 7

Table 2. Weed

California native

et al., in press.

-control

procedures

for enhancing

establishment

of

perennial

grassesin

rights-of-way.

Adapted

from Bugg

Objective

Year Months Herbicide Procedure^ Alternative Procedure Reduce weed plant population and seed reservoir prior to seedbed prepara¬ tion 1-2 years before seeding. February - March, April-May. Application of glyphosate (Roundup®)orthe"'softresidual"herbicide oryzalin (Surflan®) to suppressexistinggrowthand seed production.

Establishsummerfallow bydisk¬

ing weeds before seed has ma¬

tured. This reduces the weedseed bank; the practicecanbeused for one ormoreyearspriortoseeding a site with native perennial grasses. In thefinalyear, it can

simultaneouslyprepare a seed bed for fall seeding of native

perennial grasses. Disking also

perpetuates the disturbedcondi¬

tions underwhichweeds prosper. Onsomesites, scraping isbetter,

because it will remove muchof

theweed seed reservoir. Mowing

before seed hasmatured canalso

beeffective againstsome species ofweeds, but others, suchas an¬

nual ryegrass and introducedan¬

nual wild barleys canproduce seed heads low tothe ground fol-lowingmowing Reduce weed popu-1ation af¬ terseedbed prepara¬ tion Septem- ber- Novem-ber

Afterwinter-annual weeds have

germinated and sprouted inre¬

sponse to rain or preirrigation,

apply glyphosate or paraquat (GramoxoneExtra®). This is af¬

terseed-bed preparationbutprior

toseeding nativegrasses.

F1a me-k i 11 emerged weed

seedlings after rains orpreirriga¬

tion, butprior toseeding native perennialgrasses. Very shallow

tillage (e.g., disking or spike-tooth harrowing) can also beef¬ fective. Shallowness isessential

to avoidbringingmore weedseed

1 8 Reduce weed popu-1 ation af¬ ter seeding but before emergence 0 f native grass seedlings Septem- ber-Novem ber Chlorsulfuron

(Telar®)^applica¬

tion tosoil following seeding of

nativegrasses,toreduce germina-tion of introduced annual broadleaf and grassweeds. This gives exellent control ofannual

ryegrass. Chlorsulfuron is the only broadleaf selective herbi¬

cide that givesgood suppression ofasteraceous (composite) weeds,

such as yellow starthistle or

pricklylettuce. It does notdeter germination of blue wildrye,

California brome, or purple

needlegrass,but does affect seed

of meadowbarley and possibly others yet to be tested. Chlorsulfuron cannotbeused ad¬

jacent to agricultural land with¬

out an intervening buffer zone.

LowratesofSimazinecanbe used tosuppresswildoat.

After seeding but before emer¬ gence ofnative grasses,flaming will kill cool-season annuals.

Timing is critical, because any

emerged native grasses will be

killed, as well. Reduce weed com¬ petition and densi¬ ties during establish¬ mentof na-tive grasses 1 February-April 2,4-D, dicamba

(Banvel®)^,

ortriclopyr (Garlon 4®) tocontrol

broadleaf weeds following

early-establishment phase of native

grasses(i.e., after native grasses

have reached the 3-leaf stage).

Triclopyris not very effective againstasteraceous weeds.

Mowing, haying, orgrazing by livestock canremove the

taller-growing and (often) more-palat¬ able winter annuals duringlate

winter and early spring. This im¬

proves the competitiveposture of the nativeperennialgrasses.

Reduce weed com¬ petition, densities, and seed production duringfirst season of native grass growth March-mid April

Wickapplication of glyphosate

to selectively kill annual rye¬

grass, ripgutbrome, wild oats, and otherweedy annual grasses

that are overtopping lower-grow¬

ing native grasses. After April,

natives are usually high enough

tobesusceptible;also, weeds will

have gonetoseed.

High mowing (6" minimum) can be used to removeseed heads of

winter-annual grasses, and thus

reduce seed bank of theseweeds in

subsequentyears. Most native

grasses produce seed later, and

can recoverfromhigh mowing at this time.

1 9 Reduce weed plant densities and seed production duringfirst season of native grass growth April-June

Dicamba can be applied for om-trol ofbroadleaf weeds. Dicamba

works betteragainst older yellow

star thistle plants thandoes

2,4-D.

Ifstands ofnatives arevigorous and producingseed, mowing or

grazing of native

perennial

grassesshouldbeavoided during this period, to allow seedmatu¬

ration. On the otherhand, ifin¬

troducedgrasses aredominantand havesetseed,haycanbemade by

mowing,raking,andbaling. The haycanbefedtolivestock. Thus,

the weed seed and excessive

residue will beremoved, andna¬

tive stands canbeaugmentedby furtherseedingsduringthesubse¬ quent autumn. Reduce warm-sea¬ songrasses. May-Septem¬ ber

Spot-spraying glyphosate for

warm-season annual and peren¬ nial grasses (Bermuda, Johnson, barnyard grasses); dust onthe

plants reduces efficacyof herbi¬

cide: underdusty conditions, in¬ crease useofadjuvants.

Mechanical control of weeds

through (hoeing, weed whipping, mowing, digging) to remove, or

prevent reseedingby, patches of

warm-season annual and peren¬

nial weeds. Inhibit germina¬ tionofwin¬ ter-annual weedseeds 2 Septem- ber- Novem-ber

Apply chlorsulfuron,granular

tri-fluralin (treflan®), oryzalin

(surflan®), and/orlow rates of simazine (Princep®) toprevent germination of annual weeds.

Theseherbicides willnotdamage

established standsof blue

wildrye, California brome. Purpleneedlegrass,meadow bar¬ ley, the wheatgrasses, and the

fescuesarenotaffected by

chlor-sulfuron once established.

Chlorsulfuronwill inhibit germi¬

nationofbroadleafweeds and an¬

nualryegrass. Low-rate applica¬ tionof simazineinhibits wild oat

germinationduringsecond year.

Selective control of remaining weedinfes¬ tations 2 February-Septem¬ ber

Glyphosateused inspot-spraying

as for first year. Dicamba canbe

used for serious infestations of

yellow starthistle, prickly let¬

tuce, and otherbroadleaf weeds.

Mowingasmentionedfor the first

yearof establishment. Spotuseof

hoe or weed whip to remove

patches annual and perennial

weeds. Maintenan ce of ma¬ ture stands 0 f native grasses 3 February-Septem¬ ber

Glyphosate used inselectivespot spraying.

Mowingasmentioned for the first

yearof establishment. Spotuseof

hoe or weed whip to remove

patches annual and perennial

weeds.

^Standard safety precautions should be observed inall use

of

herbicides.

Restricted

herbicides

mustbeused inaccordance withcounty,state,and federal regulations. For information regard¬ ingpermitsand usage, contact countyagriculturalcommissioners'offices.

^Chlorsulfuroncanhavesevereeffectsonsensitivenon-targetspecies,and it should beavoided

where runoffordriftonto sensitive sites islikely

. Specifically,itcannotbe used in oron the

banks ofirrigation ditches and canals,

^2,4-D

and dicannba arerestricted-useherbicides, and shouldbe usedonly withcare. Donotuse dicamba where downward orlateral movementofwaterwillbring it intocontact with desir¬ableplants. Also avoid applicationortakesteps tominimize driftontosensitive plants when temperature exceeds85®F(30®C),

Figure

1.

Flowering

Periods

of

Native

Insectary

Trees

and

Shrubs

Salix tasiolepis (Arroyo WiUow)

Salix lasiamdra (Ytllow Willow)

Ceanothus euneatus (A California

Lilac)

Bacckaris viminea (Mule Fat)

Salix goodingii ssp, variabilis

(Gooding's

Willow)

Salix laevigata (Red Willow)Prunus ilicifolla (Holly-Leaf Cherry)

Rhamnus californlca (California

Coffeeberry)

Sambucus caerulea (Blue Elderberry)

Heteromeles arbutifolia (Toyon)

Eriogonum fasciculatum

(California

Buckwheat)

Figure

2.

Flowering

Periods

of

Wild Insectary Forbs

Jan Feb

1

MarApr

1

May

June July Aug Sep Oct Nov DecStellaria media (Chickweed)

<

^ ^1 f __

4..^

J

L

Euphorbia maculata (Prostrate Spurge) ...1... I- 1 ;

Polygonum aviculare (Common Knotweed) 1

=3:

Ammi visnaga (Toothpick Ammi) : { 1

Daucus carota (Wild Carrot) •

.Jfc

L:;y

,Foeniculum vulgare var, dulce (Sweet Fennel)

.J

>=

A < Asclepias fascicularis (Milkweed)Xanthium spinosum (Spiny Clotbur)

'

<

i i

—

23

Figure 3

Suggested

Roadside

Native

Prairie

Complexes

Native Prairie

Complex

#1

Pavement

edge: Pine

bluegrass (Poa

scahrella

Roadside berm: Red fescue

{Festuca

rubra)

and

California

brome

{Bromus

carinatus).

Inner ditchbank: Meadow

barley

(Hordeum

hrachy

anther um).

Ditch bed: Meadow

barley.

Outer ditchbank: Blue

wildrye.

Fieldside berm and field

edge:

Creeping

wildrye.

Native PrairieComplex

#2

Pavement

edge:

Pine

bluegrass

and

Idaho

fescue {Festuca

idahoen-sis).

Roadside berm: Pine

bluegrass,

Idaho

fescue,

purple

needlegrass

{Stipa

pulchra),

and

squirreltail

{Sitanion

jubatum).

Inner ditchbank: Meadow

barley,

Idaho fescue,

purple

needlegrass,

nodding

stipa

{Stipa

cernua),

California

oniongrass

{Melica

califor-nica).

Ditch bed: Meadow

barley,

purple

needlegrass,

and

spikerush

{Eleocharis

spp.).

24

Fieldside berm: Blue

wildrye, California brome, and

creeping

wildrye.

25

Appendix 1:

Beneficial Insects

and

their

Associations

with

Trees,

Shrubs,

Cover

Crops,

and

Weeds

(Adapted

from

Bugg,

1990)

Beneficial insects include parasites and predators. Parasites are usually more re¬ stricted as to which insects theywill attack. Some predators may be fairly

specialized,

as well, but many are generalists - - feeding opportunistically on various

insects

and

mites. Generalist predators may be especially importantin field andvegetable

crops, becausethey can persist in the absence of pests, may arrive in the cropfirst,

and

may act to preempt or slow down pest outbreaks. Some importantbeneficial insects

have

special plant associations.BIgeyed Bugs {Geocorisspp., Lygaeldae) are

opportunistic

predators

on awide

range of insects and mites, and are. They will also feed on nectar.

They

areespecially

important from May to mid July when they are arecommonly

found

onmelon,

okra,

pepper, and squash plants. These predators can be

abundant

in

stands

of

commonknotweed {Polygonum avicuiare) along field margins. They can also

build

upin

cool-season cover crops, like berseem clover {Trifolium alexandrium) , and subterranean

clovers, {Trifolium subterraneum), and disperse to adjoining

vegetable

cropswhen

the

clovers die early summer.Hoverflies (Syrphldae) often resemble stinging wasps or bees. Manyare

important

predators of aphids. Adult hoverflies are principally flower

visitors, feeding

onnectar

and pollen. The larvae are maggots, and these attack aphids.

Wind

shelter

is

veryim¬

portant to syrphids. Nectar is probably important as an

"energy

food"

tosustain the

hoverflies. Dietary pollen is important for reproduction. Flowering

buckwheat

(Fagopyrum esculentum), commonly used as acover crop, is

attractive

tosyrphid

flies.

Among weeds common in California, adult syrphids have been

shown

tobe

attracted to

corn spurry {Spergula arvensis) . Allograptaspp.,

Sphaerophoria

spp.,and

Paragus

tibialisv^ere observed at flowers of common knotweed. Toothpick ammi {Ammi visnaga) attracted Scaeva pyrastri, Eupeodes voiucris, Metasyrphus, Melanostoma. In summer,

we observed Allograpta obliqua, Sphaerophoriaspp., and Paragus

tibialis. Among

plants

suitable forwindbreaks or hedgerows, syrphids are heavily drawn to such native plants

as California lilacs, {Ceanothus spp.); coyote brush { Baccharis

pilularis),

holly-leaved

cherry {Prunusilicifolia) , and wild buckwheats {Eriogonumspp.).

The

soapbark tree

{Quillaja saponaria) was shown to attract Scaeva

pyrastri,

Metasyrphus,

and

Melanostoma.

Lady Beetles (Coccinellldae) are important predators of

aphids

and

other

soft-bodied insects. Convergent lady beetle {Hippodamiaconvergens) is important in

field,

vegetable, and orchard crops; ash-gray lady beetle {Olla

v-nigrum) is

mainly impor¬

tant in tree crops. In the late spring, aphids usually disappear fromCalifornian

grasslands and most crops, so, out ofdesperation, convergenet

lady

beetle feeds

onpollen

and nectar. This species is extremely abundant on flowering

soapbark

treefrom

mid

June through late June. Nectar and pollen are important in building upfat

reservesin

the beetles. Convergent lady beetle will seek bunchgrasses and form great masses of beetles that may remain dormant through the summer and early winter.If bunchgrasses

are not available on agricultural field margins, convergent lady beetle may

fly

topro-26

viding cover crops that harbor aphlds or other alternate prey. A Mixture of hairy vetch ( Vicia vHlosa), and rye {Secale cereale) works well in the cool season, and hemp

ses-bania, {Sesbania exaltata) may prove useful during the summer. Shrubs and trees can also harbor aphids that sustain lady beetles. Black locust {Robinia pseudoacacea) ,

saltbush {Atriplex spp.), and California coffee berry ,{Rhamnus californica) appear promising in this regard.

Minute Pirate Bug (Or/us fr/sf/co/or, Anthocoridae) These tiny bugs are

important predators of corn earworm. They mainly attack the eggs of these and other

moths. Theyare common in the silks of corn, and can also build up on flowering cover crops, shrubs, and weeds. Particularly potent sources are hairy vetch and 'Lana' vetch, toothpick ammi, buckwheat, and wild buckwheats.

Green Lacewings (Chrysopidae) are predatory in the larval stages, and for some

species in the adult stage. In other species, adults feed only on nectar, pollen, and hon-eydew. Comanche lacewing {Chrysoperia comanche) is extremely abundant on flowering soapbark tree from mid June through mid July, and on and bottle tree {Brachychiton populneum) from mid June into October.

Brown Lacewings (Hemeroblidae) are predatory in the adult and larval stages, and

have been shown to be important predators of artichoke plume moth in California.

Adults also feed on nectar, pollen, and honeydew, and are extremely abundant on flow¬ ering soapbark tree late at night, during June, and at bottle tree flowers from June into

October.

Parasitic Wasps (Braconidae, Chaicidoidea, and ichneumonidae) are im¬

portant in biological control of insect pests, and may rely on honeydew or pollen and

nectar in the adult stages. In Massachusetts, flowering sweet fennel {Foeniculum

vul-gare war. dulce) planted amid an organic market garden attracted 48 species of

Ichneumonidae. Fennel is probably also important for parasitic wasps in California, as

has been shown for common knotweed and toothpick ammi. Twenty species of

Ichneumonidae were observed taking extraflorat nectarfrom faba bean {Vicia faba) from late September through late October. For unknown reasons, few ichneumonids visit buckwheat or wild buckwheats.

Predatory Wasps include both social (Vespidae) and solitary species {Eumenidae and Sphecidae). The Vespidae include paper wasps and yellowjackets, which attack many

species of caterpillars. Eumenidae are also prey mainly on caterpillars. Solitary wasps

of the Sphecidae, as a group, attack wide ranges of insects, including caterpillars,

crickets, and weevils. All thesewasps require nesting sites. Many solitary species are

diggerwasps that nest in sandy areas. Some social wasps also nest in the ground, others

undereaves of buildings or in trees. Social and solitary wasps rely heavily on nectar, and commonly visit flowers and extrafloral nectaries. In Massachusetts, sweet fennel planted amid an organic market garden flowered throughout the 12 weeks of sampling. Hymenoptera collected from sweetfennel at two sites included four species of Sphecidae (solitary wasps) and four of Vespidae (social wasps). Flowering spearmint {Mentha spicata) attracted six species ofSphecidae, two of Eumenidae, and two of Vespidae. Cover

crops thatattract many predatory wasps include buckwheat, cowpea {Vigna unguicuiata

ssp. unguicuiata), and white and yellow sweetclovers {Melilotus alba and M. officinalis) .

In Massachusetts, eighteen types of wasps were obtained from buckwheat, and eleven

from annual white sweetclover. In Georgia, buckwheat attracted 9 types of Sphecidae, 2 types of Eumenidae, and onetype of Vespidae, whereas extrafloral nectar of cowpea at¬ tracted 10types of Sphecidae, 6 of Vespidae, and 4 of Pompilidae.

Tachinid Flies (Tachinidae) include numerous species that parasitize

stink

bugs,

squash bugs, and the caterpillar stages of various

moths and

butterflies.

Many

of these

flies are relianton nectar and pollen during the adult stage. Seven types oftachinidwere collected from toothpick ammi. Buckwheat, wild buckwheat, California coffeeberry , coyotebrush, other Baccharisspp., toyon

{Heteromeles

arbutifolia), and white

sweet-clover are also heavily visited.

Softwinged Flower Beetle {Collops vittatus) is a brightly-colored

insect,

with

wing covers striped with bright red and metallic blue-green. Adults

feed

on manypests,

and are commonly found running rapidly over thefoliage ofvegetable crops,

searching

for eggs of moths. Larvae are pink and crawl about on the soil surface,feeding

onother

insects. Adults are often encountered feeding atthe extrafloral nectaries of cowpeas or