Stature

and Weight

Status

of Children

in an

Urban

Kindergarten

Population

Shiriki K. Kumanyika, PhD, MPH; Sandra L. Huffman, ScD; Mary Ellen

Bradshaw, MD; Hattie WaIler, BSN, MSN; Alan Ross, PhD; Mary

Serdula, MD; and David Paige, MD, MPH

From the Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland; the District of Columbia Commission of Public Health, Washington, DC; and the Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, Georgia

ABSTRACT. To assess the prevalence of growth problems

among school entrants in an urban population who were not preselected on poverty or other nutritional risk cri-teria, we analyzed height and weight measurements for

5170 4- and 5-year-old children (91.9% black, 5.5% white,

and 2.6% Hispanic) who enrolled in District of Columbia public school kindergartens in the Fall of 1985. Compared to the National Center for Health Statistics reference, the white girls and boys were of average height, Hispanic girls were of average height, and Hispanic boys were shorter than average. The black girls and boys were taller than average. In light of published evidence for black-white differences in the timing and duration of growth, we tentatively attributed this tall stature to advanced skeletal maturation of the black children relative to the predominantly white United States population growth

standards. Underweight was virtually absent in this

pop-ulation. Excess overweight was noted in all sex-racial! ethnic subgroups, particularly among Hispanic children. However, the extent to which overweight (high weight-for-height percentile) represents obesity in kindergarten-aged children and in different racial/ethnic groups needs clarification before the implications of the finding of

excess overweight can be fully understood. Overall, the

growth of these children was on a par with the National Center for Health Statistics growth reference population.

Pediatrics. 1990;85:783-790; growth, children, black, His-panic, overweight.

In the United States, surveys of children who

have been selected on the basis of low income or

other nutritional risk criteria show an excessive prevalence of short stature, underweight, and

over-Received for publication Mar 1, 1989; accepted Apr 24, 1989 Reprint requests to (S. K. K.) Dept of Nutrition, 5-126 Hender-son Bldg, Penn State University, University Park, PA

16802-6597.

PEDIATRICS (ISSN 0031 4005). Copyright © 1990 by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

weight in some age-race/ethnic groups.’5 For

ex-ample, Alvarez et al’ reported a 21% prevalence of

growth stunting and a 14% prevalence of

under-nutrition among low-income black and Hispanic children in a neighborhood health center in Boston, citing comparable rates for children in some devel-oping countries. Scholl et al#{176}reported a higher than

expected prevalence of short stature among white

and Hispanic children in a poor community in

southern New Jersey. The Centers for Disease

Control3 reported an excess of short stature and

underweight among infants and preschool children

in several age-racial/ethnic groups. The Centers for Disease Control data are a compilation of data on

subsets

of

children in numerous states and localitieswho qualify for and have actually been enrolled in

public health nutrition programs such as the

Supplemental Feeding Program for Women,

In-fants and Children or the Early Periodic, Screening,

Diagnosis and Treatment Program. A high

preva-lence of overweight was also noted in both the New

Jersey#{176} and the Centers for Disease Control3 popu-lation.

In contrast to these studies in high-risk

popula-tions, we assessed the prevalence of stature and

weight problems in an unselected population of public school children at the point of kindergarten

entry. We were interested in whether (given the

now long-standing availability of programs such as

Supplemental Feeding Program for Women,

In-fants, and Children that focus on children in the preschool age range#{176}) the heights and weights of

children entering an urban public school system

were on a par with the National Center for Health Statistics growth reference population.7 The survey

was done in the District of Columbia, which has a

METHODS

Data Collection

The data were collected in conjunction with a

Centers for Disease Control-sponsored pilot project

concerning potential nutrition surveillance

adap-tations of school height and weight measurements.8

Nine pediatric nurse practitioners and four

com-munity health nurses, usually assisted by one or

two health technicians, collected height and weight

data in all 120 District of Columbia elementary

schools during September through December, 1985.

In collecting the data, they used an established

mechanism for routine, annual height and weight

screening of public school children by the Bureau

of School Health Services, a subdivision of the

District of Columbia Commission of Public Health.

Some modifications in the usual Bureau of School

Health Services procedure were introduced to meet

the Centers for Diseases Control requirements for

standardization and to make centralized data

col-lection easier.

Before data collection, beam balance scales were

checked and either certified as accurate to the 0.25

pound or tagged as nonworking. Portable, strain

gauge digital scales accurate to 0.1 pound (SECA,

Model 770000) were used in schools that did not

have beam balance scales or that did not have

working, certified scales. For height measurements, a metal wall tape was mounted in a suitable location

at each elementary school and used with a

hand-held right-angle board for positioning of the child’s

head. Children were measured in stocking feet,

dressed, but with minimal indoor clothing. Height

was measured in inches to the nearest 0.25 inch.

Weight was measured in pounds to the nearest 0.25

pound.

A quality assurance manual provided the school

nurses with detailed instructions for taking

stand-ardized height and weight measurements under the

specific field conditions in District of Columbia elementary schools. One week before the beginning of data collection, the school health teams attended

a centralized all-day training session. Centers for

Disease Control staff members conducted

standard-ization exercises in height and weight

measure-ments as part of this training. One of the authors (S. L. H.) visited each team in the field during the first or second week of data collection to provide further guidance in implementing the measurement protocol.

Data Processing and Analyses

Data sheets were compiled centrally by the

Bu-reau of School Health Services and delivered to

Johns Hopkins for processing and analysis. Birth

date, race/ethnicity (as designated on the school

registration form), and home address data for each

child, obtained on computer tape from the central

administration of the District of Columbia Public

Schools, were merged with the height and weight

data. The socioeconomic status distribution of the

school entrant population was approximated by

matching each child’s home address to a census

tract code that was linked to a set of 1980 census tract indicators.

At the time of data collection, 6252 children were

listed on kindergarten class rolls in District of

Columbia public elementary schools. No data were

available for the 4% of children who were absent

on the day their class was measured. The final data

set included 5170 children, 86% of those present

for screening. The exclusions (n = 832) were as

follows: 398 children for whom no date of birth was

obtained; 155 children aged < 48 months or 72

months (to limit the data set to 4- and 5-year-old

children); 6 children for whom a health problem or

possible error affecting the measurement had been

noted at the time of screening; 55 children in racial categories with insufficient numbers for analysis

(50 Asian American children and 5 American

In-dian children); 42 children for whom race was

un-known; 176 children flagged by the Centers for

Disease Contol subroutine as having “impossible”

(low or high extremes) standard deviation scores

(Z) for height for age (-6 > Z > +6), weight for age (-6 > Z > +6), or weight for height (-4 > Z> +6).

Percentiles of height for age, weight for age, and

weight for height were calculated for each child

with the Centers for Disease Control

Anthropo-metric Software.9 These percentiles refer to the

National Center for Health Statistics growth

ref-erence population.7 In effect, a height-for-age or

weight-for-age percentile score is a sex-specific,

age-adjusted observation. Weight for height

per-centiles are sex-specific but assumed to be

age-independent.7 The prevalence of short stature,

un-derweight, and overweight was calculated using the

Centers for Disease Control Pediatric Nutrition

Surveillance System definitions,2 as follows: short

stature = height for age less than the fifth

percent-ile; underweight = weight for height less than the

fifth percentile; overweight = weight for height

more than the 95th percentile. All analyses were

done on a microcomputer with Statpac.’#{176}

RESULTS

Characteristics of the District of Columbia

Kindergarten Population

The age distribution of the kindergarten entrants

Age* (mo) Height (cm) (in) Weight (kg) (ib) White (n = 146)

64.8 (3.6) 113.0 (5.6) 44.5 (2.2) 20.4 (2.8) 45.3 (6.2) Hispanic (n = 78)

64.8 (4.0) 111.3 (5.6) 43.8 (2.2) 20.5 (3.8) 45.5 (8.5) Black

___________

(n = 2431) ___________63.7 (3.6) 112.5 (5.3) 44.3 (2.1) 20.1 (3.1) 44.7 (6.9) Girls (Mean (SD))

White Black Hispanic (n = 137) (n = 2319) (n = 59)

64.6 (3.7) 63.7 (3.6) 64.7 (3.4) 110.5 (5.3) 112.0 (5.3) 111.0 (4.6) 43.5 (2.1) 44.1 (2.1) 43.7 (1.8) 19.2 (2.7) 19.8 (3.5) 20.9 (4.1) 42.7 (6.1) 44.0 (7.7) 46.5 (9.0) Age (mo)

Height (cm) (in) Weight (kg) (lb)

wAge at screening.

TABLE 4. Height for Age, Weight for Age, and Weight

for Height of Public School Kindergarten Entrants, Dis-trict of Columbia, Fall 1985: Mean Percentiles (95% Confidence Intervals) by Sex and Race/Ethnicity

Sex Height for Age

White Black Hispanic

Boys Girls 53.0 (48.3, 57.8) 47.9 (43.0, 52.8) 52.9 (51.8, 54.1) 59.6 (58.4, 60.7)

Weight for Age

42.1 (35.2, 48.9)

50.1 (42.1, 58.0)

White Black Hispanic

Boys Girls 58.3 (53.9, 62.8) 56.4 (51.9, 60.8) 56.9 (55.8, 58.0) 61.6 (60.4, 62.7)

Weight for Height

55.8 (48.9, 62.8)

67.9 (60.8, 75.0)

White Black Hispanic

Boys Girls 59.4 (55.1, 63.8) 59.8 (55.8, 64.2) 56.5 (55.5, 57.6) 57.3 (56.2, 58.4) 64.6 (58.4, 70.7) 72.0 (65.1, 78.8)

TABLE 1. Age Distribution* of Public School Kinder- TABLE 2. Racial and Ethnic Distribution of Public

garten Entrants,t District of Columbia, Fall 1985 School Kindergarten Entrants,* District of Columbia, Fall 1985, Total and by Sex

Age (mo) n Percent Age (mo) n Percent 48.0-55.99 11 0.2 64.0-64.99 490 9.5 56.0-56.99 38 0.7 65.0-65.99 400 7.7 57.0-57.99 170 3.3 66.0-66.99 399 7.7 58.0-58.99 318 6.2 67.0-67.99 391 7.6

59.0-59.99 401 7.8 68.0-68.99 396 7.7

60.0-60.99 432 8.4 69.0-69.99 257 5.0 61.0-61.99 460 8.9 70.0-70.99 108 2.1 62.0-62.99 426 8.2 71.0-71.99 27 0.5

63.0-63.99 446 8.6

Total 100.0 Race Boys n Percent Girls n Percent Total n Percent

Black 2431 (91.6) 2319 (92.2) 4750 (91.9)

White 146 (5.5) 137 (5.4) 283 (5.5)

Hispanic 78 (2.9)

2655 (100.0)

59 (2.3) 2515 (99.9)

137 (2.6) 5170 (100.0) *After exclu sions described in the text.

*Age was computed by subtracting birth date from TABLE 3. Age, Height, and Weight Characteristics of

screening date. Public School Kindergarten Entrants, District of

Colum-tAfter exclusions described in the text. bia, Fall 1985, by Sex and Race/Ethnicity Boys (Mean (SD))

Eighty-two percent were 5 years old, and all but 11

of the 4-year-old children were in the last third of

__________

__________

__________

their fourth year. The sex and racial/ethnic

distri-bution is shown in Table 2. Ninety-two percent of

the children were black. Birthplace was not

re-corded for the Hispanic children. The origins of the

District of Columbia Hispanic population are

largely Central American (not including Mexico) (49%), South American (25%), and Caribbean

(11%).h1 Based on census tract information, the

kindergarten population included children from all

District of Columbia residence areas and socioeco-nomic strata. However, in comparison to the overall

District of Columbia population,#{176}2 white children

and children from high-income census tracts were

underrepresented. The white children in the public school population lived in higher socioeconomic status census tracts than the black and Hispanic children.

Raw data on age, height, and weight by sex and

race/ethnicity are summarized in Table 3. The age

distributions of the boys and girls were similar

within race/ethnicity, but the black children were __________________________________

younger than the white and Hispanic children. ____________________________

__________

Stature and Weight Status Relative to National

Center for Health Statistics Growth Reference

Population

The mean percentiles of the anthropometric van- ____________________________________________

ables for each sex-race/ethnic group are given in

Table 4. The reference distributions, when

trans-formed into percentiles, are centered at a mean of

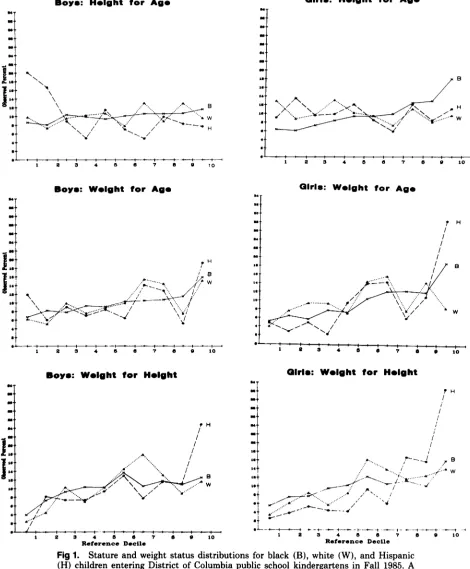

50. The observed percentile distributions are shown

in Figure 1 as the percent of kindergarten entrants ________________________________

who fell within each decile of the National Center ________________________________

for Health Statistics reference. Using this

ap-proach, if the observed distribution is identical to the reference distribution, 10% of the observations

Boys: W#{149}lght for Ags

I

5’

I

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 0 10

Girls: Wsight for Ags

H

B

w

1 2 3 4 o

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 6 9 10

Boys: Wslght for H.lght

2 3 4 6 C I C P 10

Reference Decile

Fig 1. Stature and weight status distributions for black (B), white (W), and Hispanic

(H) children entering District of Columbia public school kindergartens in Fall 1985. A distribution that is identical to the National Center for Health Statistics reference distribution would have 10% of the observations in each decile.

is shifted to the right of the National Center for

Health Statistics reference will appear as an

up-ward gradient, with less than 10% in the lower

deciles and more than 10% in the higher deciles. Stature. Black girls in the District of Columbia kindergarten population tended to be relatively tall.

The height for age graph for black girls (Fig 1)

shows an upward gradient from about 6% in the

shortest reference decile to 12% and 18% in the

deciles at the tallest end of the reference

distnibu-tion. Consistent with the impression of a

right-shifted height distribution for black girls, their

Boys:

H&ght for Ags Girls: H#{149}ight for Ag#{149}N N

\

N/H

-.--t 4 I ‘ I

-$-

-I #{176}I ‘ i #{149} #{176} -I- +-t “--I1 2 3 4 5 0 r a a io

pH

‘..‘ ‘.“

....‘ I’ /1..”

Girls: Wslght for H#{149}lght

/i

- I

- Ii

I

is I

a#{149}r .“.. ‘.. ,p-’---4 ,. B

‘t

,..

.&,... .,/ .. ./-:i’*:

:

-‘St ,,,... ‘ /1’ N

St /

‘+ #{163}“ 4

..--‘-- .-

--

$-1 2 3 4 6 6 7 a 9 10

30

28

26

24

22

20 18

6

)3 3

mean height for age was at the 59.6 percentile

(Table 4). The observed height for age distributions

and mean percentiles for Hispanic girls and white

girls were roughly comparable to the reference

dis-tnibution (Fig 1 and Table 4). The data for white

girls suggest a modest shift toward the shorter end of the distribution.

Hispanic boys were relatively short: more than

one third were in the two lowest deciles of the

reference distribution of height for age (Fig 1), and their mean height for age was at the 42.1 percentile

(Table 4). Black boys tended to be tall, but not to

the extent of black girls. The height for age

distni-bution for white boys approximated that of the

reference distribution, with perhaps a modest tend-ency toward tallness.

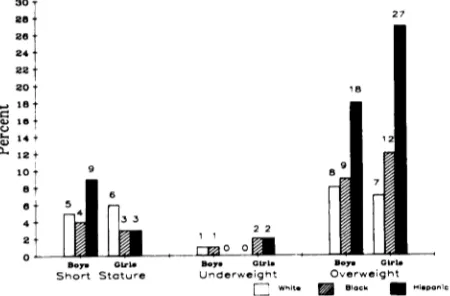

Consistent with the impression from the height

for age distributions, only Hispanic boys had an excess prevalence of short stature (ie, >5% below the fifth percentile) (Fig 2).

The pattern of male-female differences in stature was inconsistent across race/ethnicity. In blacks

and Hispanics, height for age percentiles were

higher in girls than boys, whereas the opposite was

true for whites. Viewed within sex, black and

His-panic girls were taller than white girls, whereas

Hispanic boys were shorter than white boys, and

height differences between black boys and white

boys were minimal. A two-way analysis of variance supported the validity of this finding, ie, the

inter-action of sex and race/ethnicity on height for age

was statistically significant (P = .014).

Weight Status. The distributions and mean pen-centiles of weight for age for boys and girls in the

three racial/ethnic groups (Fig 1 and Table 4)

in-dicate that the District of Columbia kindergarten

population as a whole was heavy relative to the

reference population. The patterns for girls were

more marked than those for boys, and the Hispanic

girls were the most extreme among the six

..-) 18 a

#{176})10

C.,

14

0.. 12 10

8

8

4

2

27

B,y

Ot’1 0 B.Short Stature Underweight Overwejght

flwit. #{149}p

Fig 2. Prevalence of short stature, underweight, and

overweight by sex and race/ethnicity, District of Colum-bia public school kindergarten entrants, Fall 1985.

subgroups. More than one quarter of the Hispanic

girls in the kindergarten population were in the

heaviest decile of the reference population; only

15% were below the 40th percentile of the reference distribution.

The distributions of weight for height show that

the District of Columbia population was heavier

than the reference population, irrespective of age

and stature. The distributions for boys and girls in all three racial/ethnic groups were shifted noticea-bly to the higher percentiles of the reference

distni-butions. Trends for white girls and boys were more

irregular than for the other groups. Hispanic chil-dren of both sexes had relatively few individuals at the lower end of the weight for height distribution

and relatively many at the high end. Whites and

blacks were relatively few at the low end, but with

lesser concentrations at the heaviest reference

de-cile compared to Hispanic boys and girls. The

prey-alence of underweight was less than the expected

5%, and the prevalence of overweight was greater

than the expected 5%, particularly among the

His-panic children (Fig 2).

Stature of Overweight Children. The stature of

the overweight and nonoverweight children is

com-pared in Table 5. In both sexes and in all three

racial/ethnic groups, overweight children have a

higher mean height for age percentile than

nonov-erweight children. This effect appeared to be more

pronounced among the black and Hispanic children

than among the white children. However, the test

for interaction in the analysis of variance did not

indicate a significant racial/ethnic difference in the

association of overweight with tallness, in either

sex.

DISCUSSION

With the caveat that the public school

kinder-garten population was somewhat less than

repre-sentative of children from certain high-income

cen-sus tracts, these data show adequate stature and

weight status among District of Columbia 4- and

5-year-old children from the perspective of

undernu-tnition, but suggest that overweight may be an

important problem. An excess of short stature

among the Hispanic boys is suggested, although not

conclusively because of the small numbers of

His-panic boys in this population. The absence or very

low prevalence of underweight in the District of

Columbia kindergarten entrant population was not

surprising. Low prevalence of underweight among

children in the United States has been reported

frequently, even in populations at high nutritional

risk due to low income or other criteria2’3’5 and

Total

n Mean (SD)

245 60.9 (31.7)

2410 51.8 (28.5) 9.1

way analysis of variance.

TABLE 5. Stature Comparison of Overweight and Nonoverweight Kindergarten

En-trants: District of Columbia Public Schools, Fall 1985, by Sex and Race/Ethnicity

Height-for-Age Percentile

Buys

White Black Hispanic

n Mean (SD) n Mean (SD) n Mean (SD)

Overweight* 12 57.8 (34.0) 219 61.6 (31.0) 14 51.5 (37.6)

Not Overweight 134 52.6 (28.3) 2212 52.1 (28.4) 64 40.0 (29.1)

Differencet 5.2 9.5 11.5

Girls

White Black Hispanic Total

n Mean (SD) n Mean (SD) n Mean (SD) n Mean (SD)

Overweight 9 51.3 (38.2) 270 70.5 (26.7) 16 61.1 (24.8) 295 69.4 (27.3)

Not Overweight 128 47.6 (28.3) 2049 58.1 (28.6) 43 46.0 (29.8) 2220 57.3 (28.8)

Difference 3.7 12.4 15.1 12.1w

*Weight for height above 95th percentile of National Center for Health Statistics reference.

tMean height for age percentile of “overweight” group minus mean for “not overweight” group.

:I:P < 0.05 for overall (within sex) difference in mean height-for-age percentile, by

two-Because attendance at the height and weight

screening was 96%, and because the exclusions

resulting from missing data were not clustered by

screening date or by school, there is no reason to

believe that our findings are influenced by a sizeable bias toward either under- or overestimation of

stat-ure and weight status problems. The

underrepre-sentation of children of higher socioeconomic status would, if anything, increase the number of children

with poverty-related nutritional deficits such as

short stature.’5

We evaluated the stature findings in black

chil-dren in the context of previously documented

evi-dence of accelerated growth among black

chil-dren,#{176}5’8resulting in an apparent absence of short

stature even in low-income black populations. For

example, in the Centers for Disease Control

data-base of selected low-income children served by

pub-lic health nutrition programs,2’3 the prevalence of

short stature among 3- and 4-year-old black

chil-dren was lower than for white, Hispanic, Native

American, or Southeast Asian children. Similarly,

the survey by Scholl et a15 of 5- to 12-year-old low-income children in New Jersey found a prevalence

of short stature among black boys and girls that

was one third to one half of the prevalence observed

among Hispanic and white children. Although tall

stature may reflect either parental stature or above-average nutritional status or both, the relatively tall stature of school-aged and preadolescent black

children relative to comparable white children has

been attributed to genetically determined

matuna-tional factors.’6’8 Timing and duration of some

stages of growth may be different in black and white

children.’9’ 20 For example, in the Ten-State

Nutni-tion Survey, the timing of ossification centers in

low-income blacks was advanced over that of whites

of modestly higher incomes, suggesting more rapid

skeletal maturation of children of African

ances-try.2’ Thus, the National Center for Health

Statis-tics reference,

which is based on a sample designed to represent the predominantly white United Statespopulation, may not properly estimate the stature

attainment of black children.

The inconsistency in male-female stature

differ-ences across race-ethnicity was not expected, but a

similar pattern was reported by Scholl et al.5 These

authors observed that the age-adjusted heights of

5- to 12-year-old black boys were 2.5 cm greater

than those of white boys, whereas age-adjusted

heights of black girls were 4.1 cm higher than those of white girls. Hispanic boys were 0.5 cm shorter

than white boys whereas, Hispanic girls were 0.9

CIII taller than white girls. The reason for this

pattern is unclear, but, at minimum, the

observa-tion suggests that pooling stature data across sex

in this age group may conceal useful information.

The overweight data imply a need for

obesity-related intervention but must be interpreted

cau-tiously. Although weight for specified height is a

standard criterion for determining obesity and one

that correlates well with the level of body fatness in adults,22 for children of certain ages weight for height indicates very little about the level of body fat.2325 For example, in a study of British boys and

using the National Center for Health Statistics

reference values, Griffiths et al25 showed that

in the upper decile of weight for height were also in the upper decile of fatness, as measured by skinfold

thickness, and less than half (41 percent) were in

the upper quartile of triceps skinfold thickness.

The fact that overweight children in this study

were taller than average is further reason to

em-phasize the distinction between overweight and

obesity in the interpretation of these data. A high weight for height percentile may reflect either

over-all maturational status and muscularity or excess

fatness. Tallness for age may also distinguish heavy

nonobese children from heavy obese children,26’27

but this possibility remains to be confirmed.25’ 28

Without skinfold data or some other measure of

body fat, the inference that the high-weight

chil-dren are tall and muscular is as valid as the

infer-ence

that they are tall and fat.Racial/ethnic differences in body proportions, not reflected in standard growth charts,29 further complicate the use of weight for height standards

to assess obesity. For example, blacks have

rela-tively longer lower extremities than whites.3#{176}’

Hispanic and white populations may differ on leg

length (shorter in Hispanics)28 and chest girths

(wider in Hispanics).30 Based on a body composition

study in Peruvian preschool-aged children, Trow-bridge et alt2 concluded that it may be necessary to

interpret weight for height indices differently in

different populations.

Nevertheless, our overweight findings are poten-tially indicative of a problem and should be explored further. Since high weight for height is a common finding in children in the United States, the

inter-pretation of this finding needs to be clarified to

permit early preventive intervention where

appro-priate and, conversely, to eliminate costly

interven-tion where inappropriate. Early preventive

inter-vention of adult obesity is particularly important

for black females and for some subgroups of

His-panic males and females for whom obesity and its

complications represent major health problems.’ 14

SUMMARY

By definition, studies focusing on children at high

nutritional risk tend to show an excess of growth

problems. In contrast, in an unselected public

school kindergarten population we observed stature similar to that of the National Center for Health Statistics growth reference population, with the possible exception of shorter than average stature

among Hispanic boys. Black children are taller than average. Although we can offer no definitive expla-nation for this in the absence of data on parental stature or nutritional status, there is a substantial literature suggesting that black children in the

pre-school age range are advanced in skeletal

matura-tion relative to the predominantly white United

States population growth reference. Underweight was virtually absent in this population, a finding typical of United States populations, even in

high-risk groups. The apparent excess of overweight is

noteworthy; however, clarification of the meaning of high weight for height in 4- and 5-year-old chil-dren and across race/ethnicity is needed before the implications of this finding can be determined. Overall, except for the possible concern about over-weight, the growth status of these children is

ade-quate.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported, in part, by a contract from the Association of Schools of Public Health in coopera-tion with the Centers for Disease Control.

We acknowledge the pediatric nurse practitioners, community health nurses, health technicians, and school health team supervisors who collected the data and the public school principals, teachers, and children who co-operated with the project. We are also grateful for the support and assistance of Dr Andrew D. McBride, former District of Columbia Commissioner of Public Health, Dr Floretta Dukes McKenzie, former Superintendent of the District of Columbia Public Schools, and Cormac Long, former Director of Quality Assurance for the District of Columbia Public Schools. Critical services were also pro-vided by Judy Gehret (Johns Hopkins), Emma Hazell, District of Columbia Office of Planning, and many others at the participating agencies and institutions.

REFERENCES

1. Alvarez SR, Herzog LW, Dietz W Jr. Nutritional status of poor black and Hispanic children in an urban neighborhood health center. Nutr Rev, 1984;4:583-589

2. Trowbridge FL. Prevalence of growth stunting and obesity: Pediatric Nutrition Surveillance System, 1982. MMWR.

1983;32:23-26

:3, Nutritional status of minority children: United States, 1986.

MMWR. 1987;36:366-369

4. Brown JE, Serdula M, Cairns K, et a!. Ethnic group differ-ences in nutritional status of young children from low-income areas of an urban county. Am J C/in Nutr,

1986;44:938-944

5. Scholl TO, Karp RI, Theophano J, et a!. Ethnic differences in growth and nutritional status: a study of’ poor schoolchil-dren in southern New Jersey. Public’ Health Rep.

1987;102:278-283

6. Rush D, Horvitz DG, Seaver WB, et a!. The national WIC evaluation. Evaluation of the special supplemental food program for women, infants, and children. I. Background and introduction. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988:48:389-393

7. Hamill PVV, Drizd TA, Johnson CL, et a!. Physical growth: National Center for Health Statistics percentiles. Am J C/in

Nutr. 1979;32:607-629

9. Jordan MD. Anthropometric software package tutorial guide and handbook. The Centers for Disease Control, Center for Health Promotion and Education, Division of Nutrition, Statistics Branch, Atlanta, Georgia. 1987

10. Statpac: Statistical Analysis Package for the IBM PC. Wal-onick Associates, mc; Minneapolis, MN. 1985

11. Hispanic Population and Characteristics in the Washington DC Metropolitan Area. Washington, DC: Comprehensive Technologies International. 1981

12. District of Columbia Office of Policy and Program Evalua-tion. Indices. A Statistical Index to District of Columbia

Services. June 1984.

13. Peck RE, Chuang M, Robbins G.E, et al. Nutritional status of Southeast Asian refugee children. Am J Public Health.

1981;71:1144-1 148

14. Dewey KG, Daniels J, Teo KS, et al. Height and weight of Southeast Asian preschool children in Northern California.

Am J Public Health. 1986;76:806-808

15. Jones DY, Nesheim MC, Habicht J-P. Influences in child growth associated with poverty in the 1970’s: An examina-tion of HANESI and HANESII, cross-sectional US national

surveys. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;42:714-724

16. Garn, SM, Clark DC, Trowbridge FL. Tendency toward greater stature in American black children. Am J Dis Child.

1973;126:164-166

17. Owen GM, Lubin AH. Anthropometric differences between black and white preschool children. Am J Dis Child.

1973;126:168-169

18. Garn SM, Clark DC. Problems in the nutritional assessment of black individuals. Am J Public Health. 1976;66:262-267 19. Wingerd J, Peritz E, Sproul A Race and stature differences

in the skeletal maturation of the hand and wrist. Ann Hum Biol. 1974:1:201-209

20. Eveleth PB. Population differences in growth. In: Falkner F, Tanner JM, eds. Human Growth. New York: Plenum Press; 1986:221-239

21. Garn SM, Clark DC. Nutrition, growth, development and maturation: findings from the Ten State Nutrition Survey of 1968-70. Pediatrics. 1975;56:306-319

22. Abraham S. National Center for Health Statistics. Obese

and OverweightAdults in the United States. Vital and Health

Statistics. Series 11, No. 230. Washington, DC: US Govern-ment Printing Office; January 1983. Dept of Health and Human Services publication 83-1680.

23. Michielutte R, Diseker RA, Corbett WT, et al. The relation-ship between weight-height indices and the triceps skinfold measure among children age 5 to 12. Am J Public Health.

1984;74:604-606

24. Cole TJ. A critique of the National Center for Health Statistics weight for height standard. Hum Biol.

1985;57:183-196

25. Griffiths M, Rivers JPW, Hoinville EA. Obesity in boys: The distinction between fatness and heaviness. Hum Nutr Clin Nutr. 1985;39C:259-269

26. Johnston FE. Health implications of childhood obesity. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:1068-1072

27. Forbes GB. Lean body mass and fat in obese children.

Pediatrics. 1964;34:308-314

28. Martorell R, Mendoza FS, Castillo RO, et a!. Short and plump physique of Mexican-American children. Am J Phys

Anthropol. 1987;73:475-487

29. Roche AF, McKigney JI. Physical growth of ethnic groups comprising the US population. Am J Dis Child. 1976;130:62-64

30. Najjar MF, Rowland M. National Center for Health Statis-tics. Anthropometric Reference Data and Prevalence of

Over-weight, United States, 1976-80. Vital and Health Statistics.

Series 11, No. 238. Washington, DC: US Government Print-ing Office; October 1987. Dept of Health and Human Serv-ices publication (PHS) 87-1688. Public Health Service. 31. Malina RM, Brown KH, Zavaleta AN. Relative lower

ex-tremity length in Mexican American and in American black and white youth. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1987;72:89-94 32. Trowbridge FL, Marks JS, de Romana GL, et al. Body

composition of Peruvian children with short stature and high weight-for-height. II. Implications for the interpreta-tion for weight-for-height as an indicator of nutritional status. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;46:411-418

33. Kumanyika 5K. Obesity in black women. Epidemiol Rev,

1987;9:31-50

34. Kumanyika 5K. Dietary and disease issues for U.S. minority populations. J Nutr Educ. In press.

THE “ME” GENERATION AS PARENTS: PART 2

I know a couple of physicians who work around the clock. During the week,

one live-in babysitter cares for their very young girl and emotionally troubled

young boy; the other live-in takes over on weekends. Recently, my 6-year-old

daughter exclaimed, “Look, Mom, Sarah has a new babysitter!” The “babysitter”

was Sarah’s mother.

Perhaps most telling is the family Halloween party we gave last October. We

invited the mother that my daughter took for the babysitter, along with her

husband and children. She never bothered to call to say she and her husband

weren’t coming. Instead, her children showed up with the babysitter. What is

happening when parents conclude that a family party means only their children

and babysitter?