Social, Economic, and Political Determinants of Child Health

Nick Spencer, MD

ABSTRACT. The Issue. This article presents a brief overview of the effects of social, economic, and political factors on child health. It starts by highlighting child poverty in rich nations, in particular the United Kingdom and the United States, and identifies the economic and political factors underlying this phenomenon. The evi-dence linking socioeconomic status and child health is briefly reviewed with particular attention to birth weight and child mental health—2 of the most important public health challenges in the 21st century. The implications for pediatricians of high levels of child poverty and the effect that these have on children are discussed. Pediat-rics 2003;112:704 –706; social, economic, political, child poverty, advocacy.

ABBREVIATION. OECD, Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development.

CHILD POVERTY IN RICH NATIONS

C

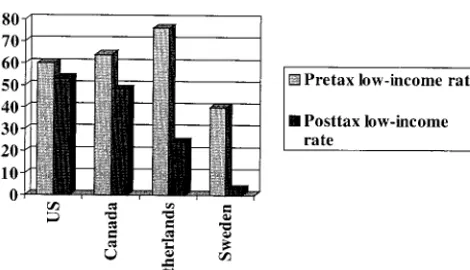

hild poverty levels (as measured bypercent-age of children in households with ⬍50% of the national median income) in the United Kingdom (19.4%) and the United States (22.4%) are among the highest in the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries.1 This is in sharp contrast to countries such as Sweden, Norway, and Belgium that have child poverty rates below 5%.1 For example, Sweden reduces “market child poverty” (the child poverty level before tax and credit transfers) by as much as 20%, whereas the United States, starting from higher market child pov-erty, reduces it by as little as 5%.

There has been a sharp increase in child poverty rates in the United Kingdom since 1979. The 1980s also saw a rise in child poverty rates in the United States. These increases in child poverty were accom-panied by an increase in income inequalities, a phe-nomenon noted in many industrial countries during the past 20 years. Children are now the largest single group living in poverty in many countries. There also has been a “feminization” of poverty—lone fe-male parents have very high rates of poverty in all OECD countries, as well as in the United States. Across the OECD countries, children in lone-parent households are 4 times more likely to be living in poverty.1

Child poverty rates are strongly correlated (posi-tive) with the proportion of households in which no adult is employed and the proportion of full-time workers earning less than two thirds of the national median wage. This suggests that countries with high levels of unemployment among families with chil-dren and low-wage economies are likely to have the highest rates of child poverty. The United Kingdom, which has experienced very high levels of unem-ployment in the past 20 years, had 19% of children living in households with no adult employed in 1999.2It is important to note that high child poverty rates are not inevitable. They result from deliberate political decisions, usually related to economic and social welfare policies.

SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS AND CHILD HEALTH Globally and historically, socioeconomic status is among the most important health determinants throughout the life course.3Young children seem to be particularly vulnerable to the effects of adverse socioeconomic status and poverty. Poverty and low socioeconomic status are associated with higher risk of death in infancy and childhood, chronic childhood illness, and many acute illnesses.3 They are also closely linked with birth weight and child mental health problems.

However, increased risk of some adverse health outcomes is not confined to the extremes of poverty and low socioeconomic status. Many child health outcomes show a social gradient, although the gra-dient varies by exposure and outcome.4 For some outcomes, the longer the child is exposed to adverse social conditions and the worse the social conditions, the greater the effect.5Birth weight shows a marked social gradient (Table 1). This has profound effects not only in infancy and childhood but also into adult life.6

Studies show a graded reduction in mean birth weight as the areas of residence become more de-prived, as measured by the Townsend Deprivation Index.9 It is not only the most deprived fifth of the infant population that is disadvantaged in terms of birth weight compared with the most privileged— the effect is finely graded by socioeconomic status. These findings contribute to our understanding of the social gradients that are noted across the life course.10

Mental health problems in children also have pro-found effects across the life course. Figure 1 shows the graded relationship between household income and emotional and behavioral problems in childhood in a recent UK study.11 Again, the effects of income

From the Department of Community Paediatrics, University of Warwick, Conventry, United Kingdom.

Received for publication Mar 14, 2003; accepted Mar 14, 2003.

Address correspondence to Thomas Tonniges, MD, FAAP, American Acad-emy of Pediatrics, Department of Community Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Blvd, Elk Grove Village, IL 60007. E-mail: ttonniges@aap.org PEDIATRICS (ISSN 0031 4005). Copyright © 2003 by the American Acad-emy of Pediatrics.

are not confined to the poorest group but have a finely graded distribution across the income range.

Cumulative and additive risk exposures over time and between generations may contribute to an un-derstanding of these gradients.4 Health behaviors, such as smoking, and concepts such as “good enough” parenting must be seen within their social, economic, and political context. They are risk factors for adverse outcomes but exert their effects as part of complex pathways working over time, across gener-ations, and at the societal as well as individual lev-el.12,13In addition to recognizing the effects of socio-economic status on child health, recent studies have demonstrated that socioeconomic status in early childhood has a significant impact on a range of adult health outcomes.14

IMPLICATIONS FOR PEDIATRICIANS Pediatricians must develop an awareness and un-derstanding of the social determinants of health if they are to contribute fully to improved child health outcomes. These determinants have been forgotten in medical education and understated in the contem-porary climate of biomedical and technologic re-sponses to child illness. I am not suggesting that we should abandon biomedical and technologic ad-vances. However, we need to see health within its social context to understand the impact of social factors on children and on their access and response to biomedical and technologic advances in treatment. It also is important that pediatricians be aware of the life course implications of early childhood effects of adverse social circumstances and how these stretch into adult life. Addressing chronic illness in

adult life is likely to require social and political in-terventions that reduce the adverse effects of social disadvantage in childhood. It is equally likely that interventions at this level will be required to reduce the prevalence of low birth weight and mental health problems in children.

Practice and service structures must seek to over-come the “inverse care law,” which states that those most at risk and most in need of services are the least likely to access them. This is a particularly pressing issue in the United States, where many children of families with low income have limited access to child health services, but it is also a problem in the United Kingdom despite the universal availability of high-quality pediatric services. Pediatricians have a spe-cial responsibility for ensuring that children of fam-ilies that are poor or have low income have services that are of equal quality to their more privileged peers. Although this may have only a marginal effect on health outcomes, it can be a vital contribution to ensuring that the disadvantage that these children already experience is not exacerbated by lack of ac-cess to services.15

Child poverty is not an “unmodifiable” variable. The situation of families with children can be im-proved, but this will require political and economic policies that are, in essence, redistributive. Higher taxes and/or the redistribution of funds to ensure that all families with children have an adequate in-come will be necessary to ensure improvements in child health (Figs 2 and 3). Given the profound ef-fects of poverty and low income on health in child-hood and across the life course, pediatricians and their organizations (local and national) have a critical

Fig 1. Social gradient in emotional and be-havioral problems by annual household in-come.

TABLE 1. Social Gradient in Birth Weight in 2 UK Studies7,8

Enumeration District Quintiles by Townsend

Deprivation Index

Mean Birth Weight (All Live) W Midlands 1991–1993

Mean Birth Weight (Singleton Only) Sheffield 1991–1993

1 (least deprived) 3393 g (3386, 3400) [n⫽33 513]

3408 g (3376, 3440) [n⫽3466]

2 3380 g (3372, 3388)

[n⫽31 146]

3374 g (3340, 3408) [n⫽3430]

3 3344 g (3337, 3351)

[n⫽36 542]

3319 g (3287, 3351) [n⫽3372]

4 3293 g (3287, 3299)

[n⫽44 757]

3282 g (3248, 3316) [n⫽3721] 5 (most deprived) 3219 g (3213, 3226)

[n⫽64 073]

3225 g (3190, 3260) [n⫽3733]

SUPPLEMENT 705

at Viet Nam:AAP Sponsored on August 30, 2020

www.aappublications.org/news

role to play in advocating for policies that protect children from a life in poverty. Advocacy can be at an individual, local, national, or international level.15 Pediatricians also have a responsibility to address the inverse care law as it applies to research. The weight of funding and interest in research is concen-trated on rare conditions and their cure, while the social determinants of health, a major cause of ill health, receive limited research funding or attention. In conducting sociomedical research, we should bear in mind that social factors exert their effects through complex pathways. The “single cause” fetishism that arises from the germ theory of disease is inadequate to explain many of the adverse health outcomes as-sociated with social inequality. Child health research must pay more attention to socioeconomic status and improve the measures used to study its effects.

CONCLUSIONS

Child poverty is increasing in the United Kingdom and the United States. Given the known impact of social, economic, environmental, and other nonmed-ical determinants on child health, an impact that continues through adulthood, it is incumbent on pe-diatrics and pediatricians to focus their efforts on dealing with the root causes of these social injustices. The Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health and the American Academy of Pediatrics, through this joint Equity Project, should establish the educa-tion, practice, and research framework to integrate these issues into the corpus of pediatrics. Much is available to be learned from our mutual experience but also from the efforts of other countries. Advocacy and political resolve will be necessary for success.

REFERENCES

1. UNICEF.Child Poverty in Rich Nations.Florence, Italy: UNICEF, Inno-centi Research Centre; 2000

2. NCH Action for Children.Factfile 2000:Facts and Figures on Issues Facing Britain’s Children. London, United Kingdom: NCH Action for Children; 1999

3. Spencer NJ. Poverty and Child Health. 2nd ed. Abingdon, United Kingdom: Radcliffe Medical; 2000

4. Spencer N. Social gradients in child health: why do they occur and what can paediatricians do about them?Ambul Child Health. 2000;6:191–202 5. Smith JR, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov P. The consequences of living in

poverty for young children’s cognitive and verbal ability and early schooling achievement. In: Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, eds.The Conse-quences of Growing Up Poor.New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997:132–189

6. Barker DJP, ed.Fetal and Infant Origins of Adult Disease.London, United Kingdom: London Papers, BMJ; 1992

7. Spencer N, Bambang S, Logan S, Gill, L. Socioeconomic status and birth weight: comparison of an area-based measure with the Registrar Gen-eral’s social class.J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:495– 498 8. Spencer NJ, Logan S, Gill L. Trends and social patterning of birth weight

in Sheffield, 1985–94. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1999;81: F138 –F140

9. Townsend P, Phillimore P, Beattie A.Health and Deprivation: Inequality and the North.Beckenham, England: Croom Helm; 1988

10. Bartley M, Power C, Blane D, Smith GD, Shipley M. Birth weight and later socioeconomic disadvantage: evidence from the 1958 British cohort study.BMJ. 1994;309:1475–1478

11. Prescott-Clarke P, Primatesta P, eds.The Health of Young People 1995–97.

London, United Kingdom: Stationery Office; 1998

12. Logan S, Spencer N. Smoking and other health related behaviour in the social and environmental context.Arch Dis Child. 1996;74:176 –179 13. Taylor J, Spencer N, Baldwin N. Social, economic, and political context

of parenting.Arch Dis Child. 2000;82:113–120

14. Kuh D, Power C, Blane D, Bartley M. Social pathways between child-hood and adult health. In: Kuh D, Ben Shlomo Y, eds.A Life Course Approach to Chronic Disease Epidemiology.Oxford, England: Oxford Med-ical Publications; 1997:69 –198

15. Spencer N. The role of the paediatrician in reducing the effects of social disadvantage on children.Curr Paediatr. 1999;9:62– 67

16. Ross DP, Scott K, Kelly M.Child Poverty: What Are the Consequences?

Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Centre for International Statistics, Canadian Council on Social Development; 1996

Fig 2. International comparisons of spending on income security compared with families’ low-income rates.16

Fig 3. Low-income rate among single-parent households before and after taxes and transfers.16

2003;112;704

Pediatrics

Nick Spencer

Social, Economic, and Political Determinants of Child Health

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/112/Supplement_3/704

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

BIBL

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/112/Supplement_3/704#

This article cites 7 articles, 5 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/advocacy_sub

Advocacy

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

at Viet Nam:AAP Sponsored on August 30, 2020

www.aappublications.org/news

2003;112;704

Pediatrics

Nick Spencer

Social, Economic, and Political Determinants of Child Health

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/112/Supplement_3/704

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.

the American Academy of Pediatrics, 345 Park Avenue, Itasca, Illinois, 60143. Copyright © 2003 has been published continuously since 1948. Pediatrics is owned, published, and trademarked by Pediatrics is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly publication, it

at Viet Nam:AAP Sponsored on August 30, 2020

www.aappublications.org/news