Adolescent Medicine Training in Pediatric Residency

Programs

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: Coverage of many adolescent medicine topics is inadequate and programs report an insufficient number of adolescent medicine faculty for the adolescent medicine rotation, according to a 1997 study.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: This study shows that previously identified problems persist and that time spent at adolescent clinical sites is short and opportunities to establish on-going clinical relationships with adolescents are limited throughout pediatric residency training.

abstract

OBJECTIVES:The aim of this study was to provide an assessment of pe-diatric residency training in adolescent medicine.

METHODS:We conducted 2 national surveys: 1 of pediatric residency pro-gram directors and the other of faculty who are responsible for the ado-lescent medicine block rotation for pediatric residents to elicit descriptive and qualitative information concerning the nature of residents’ ambula-tory care training experience in adolescent medicine and the workforce issues that affect the experience.

RESULTS:Required adolescent medicine topics that are well covered per-tain to normal development, interviewing, and sexual issues. Those least well covered concern the effects of violence, motor vehicle safety, sports medicine, and chronic illness. Shortages of adolescent medicine special-ists, addictions counselors, psychiatrspecial-ists, and other health professionals who are knowledgeable about adolescents frequently limit pediatric resi-dency training in adolescent medicine. Considerable variation exists in the timing of the mandatory adolescent medicine block rotation, the clinic sites used for ambulatory care training, and the range of services offered at the predominant training sites. In addition, residents’ continuity clinic experience often does not include adolescent patients; thus, pediatric res-idents do not have opportunities to establish ongoing therapeutic relation-ships with adolescents over time. Both program and rotation directors had similar opinions about adolescent medicine training.

CONCLUSIONS:Significant variation and gaps exist in adolescent medi-cine ambulatory care training in pediatric residency programs through-out the United States. For addressing the shortcomings in many programs, the quality of the block rotation should be improved and efforts should be made to teach adolescent medicine in continuity, general pediatric, and specialty clinics. In addition, renewed attention should be given to articu-lating the core competencies needed to care for adolescents.Pediatrics

2010;125:165–172 AUTHORS:Harriette B. Fox, MSS,aMargaret A. McManus,

MHS,aJonathan D. Klein, MD, MPH,bAngela Diaz, MD, MPH,cArthur B. Elster, MD,dMarianne E. Felice, MD,e David W. Kaplan, MD, MPH,fCharles J. Wibbelsman, MD,g and Jane E. Wilson, MDa

aNational Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health, Washington, DC;bDepartment of Pediatrics, University of Rochester School of Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota;cDepartment of Pediatrics, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York;dAmerican Medical Association, Chicago, Illinois;eDepartment of Pediatrics, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Boston,

Massachusetts;fDepartment of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, University of Colorado, Denver, Colorado;gDepartment of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, University of California San Francisco, California

KEY WORDS

graduate medical education, pediatric residency training, adolescent health

ABBREVIATION

ACGME—Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education

Dr Klein is currently at the American Academy of Pediatrics, Chicago, IL. Dr Elster has retired from the American Medical Association. Dr Wilson is currently practicing with the Potomac Timonium Medical Center, Baltimore, MD.

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2008-3740

doi:10.1542/peds.2008-3740

Accepted for publication Jul 30, 2009

Address correspondence to Harriette Fox, MSS, National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health, 750 17th St NW, Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20006. E-mail: hfox@thenationalalliance.org

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright © 2009 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE:The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

day, 26% of all adolescents have a sex-ually transmitted disease,1 21% have a diagnosed mental health condition,2 16% are overweight,3 and 8% have a substance abuse or dependence disor-der.4As is well documented in the liter-ature, many of these major health problems reflect the high rates of risk-taking behaviors that are associated with adolescence and the now under-stood slow maturation of areas of the brain that control impulse and judg-ment; however, genetic and biological factors are also strong contributors to adolescent health status, as are social factors, such as stress, unsafe neigh-borhoods, family dysfunction, and the absence of resources for exercise and nutrition.

Despite the introduction of a manda-tory 1-month adolescent medicine ro-tation in 1997, many pediatricians re-portedly do not think that they are adequately prepared to care for ado-lescents. A study by Freed et al5found that just 17% of general pediatricians believed that they were very well trained to care for adolescents aged 12 to 18, whereas 65% believed that they were very well prepared to care for infants and 47% believed that they were very well prepared to care for children aged 2 to 11. Consistent with this finding, other research showed that practicing pediatricians reported a lack of adequate training on issues such as gynecologic and pregnancy care,6,7anxiety and depres-sion,8 suicide,9 violence-prevention counseling,10how to manage a positive screen result for substance abuse in adolescents,11and smoking-cessation counseling.12

The continued disparity between train-ing and pediatricians’ practice needs is particularly significant in light of the increasing role that pediatricians are playing in adolescent health care.

Pe-few decades, and family physicians’ share of adolescent visits has de-creased correspondingly.13Relative to family physicians, pediatricians’ share of adolescent visits are particularly high in urban and suburban areas.14At the same time, the onset of puberty is occurring at an earlier age, and pedia-tricians must be prepared to address the sexual and behavioral health risk issues of adolescents as young as 10 or 1115and to foster cognitive matu-rity about these risks even earlier in childhood.

Although the topic has received peri-odic attention, a comprehensive as-sessment of pediatric residency train-ing in adolescent medicine has not been conducted since 1997.16Now that the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) require-ments for training in adolescent med-icine have been in effect for ⬎10 years,17this seems to be an opportune time to reevaluate the adequacy of training that pediatric residents re-ceive in adolescent medicine.

METHODS

This study examined the current state of adolescent medicine training in pediatric residency programs in the United States. Findings are based on 2 national surveys conducted by the National Alliance to Advance Adoles-cent Health (formerly InAdoles-center Strate-gies) in the summer of 2007: 1 of pedi-atric residency program directors and the other of the pediatric residency faculty responsible for the adolescent medicine block rotation. The questions were structured to elicit both descrip-tive and qualitadescrip-tive information con-cerning the nature of residents’ train-ing experience in adolescent medicine as well as the workforce issues that affect this experience. When opinions were sought, respondents were asked

A total of 196 programs were included in the study. The residency program directors’ survey achieved a 78% re-sponse rate, and the adolescent medi-cine block rotation faculty survey, which was considerably longer, achieved a response rate of 76%. We have re-sponses for both the residency pro-gram director and the adolescent medicine faculty member responsible for the block rotation in 55% of pediat-ric residency programs. For the most part, questions in the 2 surveys were not duplicative; they were designed to obtain different perspectives and information.

The surveys were pilot tested with res-idency program directors and faculty who were responsible for the block ro-tation at 4 pediatric residency pro-grams to ensure that the questions were clearly worded and that the con-tent accurately reflected the nature of the issues that pediatric residency programs face. Copies of the survey in-struments are available on request from the authors.

resi-dency program director survey was approved by the Association of Pediat-ric Program Directors and was granted institutional review board exemption by Independent Review Consulting, Inc. The Association of Pediatric Program Directors took responsibility for send-ing a link to the electronic version of the survey to its members via their list-serv, mailing a paper version of the survey, and sending 2 mail reminders. Descriptive statistics and basic tabula-tions for both surveys were compiled, and data were analyzed with SPSS for Windows 10.0. Statistical analyses in-cluded frequencies and cross-tabs with the Pearson2test to identify sta-tistically significant differences be-tween subgroups of the population surveyed.

RESULTS

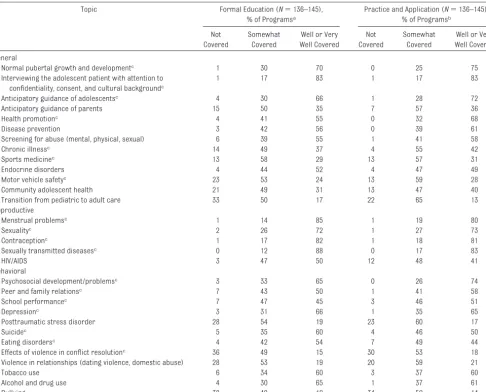

Adolescent Medicine Topics Covered During Pediatric Residency Training

Although residency programs are ex-pected to provide training on a broad range of adolescent medicine topics throughout the residency, the extent to which they are meeting this objective seems to vary considerably across programs, with few programs prepar-ing residents well in all areas. Adoles-cent medicine faculty who were re-sponsible for the 1-month rotation reported that 25% of programs are covering three quarters or more of the required adolescent medicine topics well or very well through both formal education and practical experiences throughout the residency, yet ⬎45% are not covering at least half of the re-quired topics well or very well and

⬃15% are not covering even one quar-ter of them well or very well.

In addition to the variation across top-ics, there is considerable variation in the extent to which specific topics are covered. Among the required topics, those most likely to be well covered

pertain to sexual health issues, normal development, and interviewing cents (Table 1). The required adoles-cent medicine topics that are least often well covered concern injury pre-vention and treatment and chronic ill-ness, topics referred to by the ACGME as common adolescent health prob-lems. Adolescent medicine faculty were also asked about their program’s coverage of certain topics that are not specifically required by the ACGME but are generally considered important to the care of adolescents, such as endo-crine disorders, substance abuse, HIV/ AIDS, and others. For these topics, cov-erage during training varied but was often poorer than for required topics.

Faculty Who Teach Adolescent Medicine

Pediatric residency programs are re-quired to have qualified faculty to teach adolescent medicine, and the vast majority have at least 1 adoles-cent medicine specialist on faculty. Only⬃5% of programs reported that they have none. Just more than 40% have between 2 and 4 adolescent med-icine specialists available to teach res-idents, and 10%, nearly all of which also train adolescent medicine fel-lows, haveⱖ5. The ratio of adolescent medicine specialists to pediatric resi-dents (including resiresi-dents in com-bined residency programs) varies sub-stantially across programs, from as many as 1 per every 3 residents to as few as 1 per every 75 residents, with the largest proportion, 45%, ranging from between 1 to 16 residents and 1 to 30 residents.

The shortage of adolescent medicine specialists and other health profes-sionals sometimes has a negative im-pact on pediatric residency training. Although 30% of residency program di-rectors reported that they have ade-quate numbers of faculty in all disci-plines to teach adolescent medicine,

almost the same proportion reported that the shortage of adolescent medi-cine specialists limits residency train-ing in adolescent medicine in their programs. In addition, a substantial proportion reported that training in adolescent medicine is limited by an inadequate number of mental health and behavioral health professionals, with as many as one third noting the negative impact on residency training as a result of a shortage of psychia-trists who care for adolescents.

Adolescent Medicine Block Rotation

The specific requirements for the ACGME-mandated 1-month adolescent medicine block rotation for pediatric residency programs results in sub-stantial variation in the timing and length of the rotation. The block rota-tion in just more than 60% of programs is scheduled exclusively during the first or second year of training. The re-mainder of programs schedule it dur-ing the third year or have some other arrangement that results in at least some residents’ waiting until their third year to have focused training in adolescent medicine. Programs gener-ally adopt the 1-month rotation quirement, with 5% of programs re-quiring a longer rotation. Although only 5% reported having a shorter mandatory block rotation, as many as 50% of programs thought that sched-uled on-call responsibilities for pediat-ric inpatient care limits training dur-ing the adolescent medicine rotation.

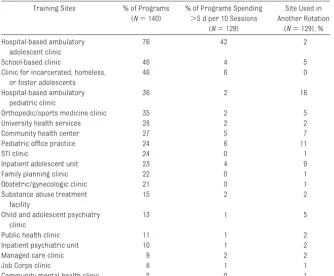

There is also little consistency with re-spect to the clinic sites used for ado-lescent medicine training and the time that residents spend at these sites. In

⬃30% of programs, residents rotate at between 1 and 3 sites during the block rotation, whereas in⬃20%, they rotate at ⱖ7 sites. For many sites, however, the actual amount of time

spent in training is often very limited, as shown in Table 2.

As reported by adolescent medicine faculty who are responsible for the ro-tation, training in adolescent medicine is limited by the absence of an adoles-cent clinic in⬃20% of pediatric resi-dency programs, limited by the lack of community-based sites in⬃30%, and limited by the absence of an adoles-cent inpatient unit in⬃45%. In addi-tion, approximately one third of resi-dency program directors reported that inadequate numbers of adoles-cent patients at rotation sites

nega-tively affects training in adolescent medicine, and the same proportion said that the need to send residents to various sites results in disparate learning experiences as well as logis-tic problems.

The main rotation site used for ambu-latory care training during the block rotation also varies from program to program, from commonly used hospital-based adolescent clinics to less frequently used sites such as school-based clinics, public health clinics, or college health services. In almost three quarters of residency

programs, adolescent medicine fac-ulty reported that the predominant training site serves as the primary care provider for the majority of ado-lescents seen. The majority of adoles-cents seen at the predominant site in almost 80% of programs are low in-come; in⬃70% of programs, they are of a racial or ethnic minority; and in almost 70% of programs, they report-edly exhibit high-risk behaviors such as substance abuse, binge drinking, or risky sexual behavior.

The predominant ambulatory care training sites for the adolescent

medi-Topic Formal Education (N⫽136–145), % of Programsa

Practice and Application (N⫽136–145), % of Programsb

Not Covered

Somewhat Covered

Well or Very Well Covered

Not Covered

Somewhat Covered

Well or Very Well Covered

General

Normal pubertal growth and developmentc 1 30 70 0 25 75

Interviewing the adolescent patient with attention to confidentiality, consent, and cultural backgroundc

1 17 83 1 17 83

Anticipatory guidance of adolescentsc 4 30 66 1 28 72

Anticipatory guidance of parents 15 50 35 7 57 36

Health promotionc 4 41 55 0 32 68

Disease prevention 3 42 56 0 39 61

Screening for abuse (mental, physical, sexual) 6 39 55 1 41 58

Chronic illnessc 14 49 37 4 55 42

Sports medicinec 13 58 29 13 57 31

Endocrine disorders 4 44 52 4 47 49

Motor vehicle safetyc 23 53 24 13 59 28

Community adolescent health 21 49 31 13 47 40

Transition from pediatric to adult care 33 50 17 22 65 13

Reproductive

Menstrual problemsc 1 14 85 1 19 80

Sexualityc 2 26 72 1 27 73

Contraceptionc 1 17 82 1 18 81

Sexually transmitted diseasesc 0 12 88 0 17 83

HIV/AIDS 3 47 50 12 48 41

Behavioral

Psychosocial development/problemsc 3 33 65 0 26 74

Peer and family relationsc 7 43 50 1 41 58

School performancec 7 47 45 3 46 51

Depressionc 3 31 66 1 35 65

Posttraumatic stress disorder 28 54 19 23 60 17

Suicidec 5 35 60 4 46 50

Eating disordersc 4 42 54 7 49 44

Effects of violence in conflict resolutionc 36 49 15 30 53 18

Violence in relationships (dating violence, domestic abuse) 28 53 19 20 59 21

Tobacco use 6 34 60 3 37 60

Alcohol and drug use 4 30 65 1 37 61

Bullying 38 49 12 34 52 14

aFormal education refers to lectures, seminars, or small-group discussions. bRefers to the practical clinical experience.

cine rotation, however, are not always able to provide a comprehensive set of adolescent health services. Al-though behavioral medicine and re-productive health are core competen-cies for training, only 40% of residency programs reported that the services furnished at the predominant training site include mental health and sub-stance abuse counseling, psycho-tropic medication, and contraception, although the proportion is slightly higher among programs in which the predominant site is physically sepa-rate from a general pediatrics clinic. With respect to the discrete services,

⬎90% of programs are able to furnish contraceptive services at the predom-inant training site and⬃75% are able to provide psychotropic medication, 66% are able to provide mental health counseling, and ⬃60% are able to provide substance abuse counseling. Among residency programs that do

not offer mental and behavioral health services at the predominant clinical site, only⬃30% have residents rotate at community mental health clinics, child and adolescent psychiatry clin-ics, inpatient psychiatric units, or sub-stance abuse treatment facilities.

Depending on the program, different types of professionals may staff the main site during the rotation. Adoles-cent medicine specialists in the vast majority of programs, but not all, reg-ularly staff these ambulatory care sites (Table 3). Nurse practitioners, psychiatric or clinical social workers, and general pediatricians regularly staff these sites far less often, whereas psychiatrists, clinical psy-chologists, and obstetricians/gynecol-ogists do so only rarely. In fact, just fewer than 20% of programs have an adolescent medicine specialist, a nurse practitioner, and a social worker

regularly staffing the main rotation site where pediatric residents are trained in adolescent medicine; only 7% have these professionals plus a health educator.

Although interdisciplinary training has been a significant focus of adolescent medicine since the beginning of the subspecialty17and working in interdis-ciplinary teams is a requirement of pe-diatric residency training,18 relatively little emphasis is placed on interdisci-plinary training in adolescent medi-cine during the block rotation in most pediatric residency programs. When asked to assess the emphasis placed on interdisciplinary care, adolescent medicine faculty in approximately one third of programs reported that little or very little emphasis is placed on this type of training; only a slightly larger proportion reported that a high or very high emphasis was placed on it. In addition, as many as one quarter of programs reportedly do not use any teaching methods that normally are associated with interdisciplinary training. Among these methods, those used most often, by 40% of programs, are lectures or seminars on

interdisci-TABLE 2 Training Sites Used for Adolescent Medicine Rotation and Time SpentaPer Site, as Reported by Adolescent Medicine Faculty Who Are Responsible for the Block Rotation in Pediatric Residency Programs

Training Sites % of Programs (N⫽140)

% of Programs Spending ⬎5 d per 10 Sessions

(N⫽129)

Site Used in Another Rotation

(N⫽129), %

Hospital-based ambulatory adolescent clinic

76 42 2

School-based clinic 46 4 5

Clinic for incarcerated, homeless, or foster adolescents

46 6 0

Hospital-based ambulatory pediatric clinic

36 2 16

Orthopedic/sports medicine clinic 35 2 5

University health services 28 2 2

Community health center 27 5 7

Pediatric office practice 24 6 11

STI clinic 24 0 1

Inpatient adolescent unit 23 4 9

Family planning clinic 22 0 1

Obstetric/gynecologic clinic 21 0 1

Substance abuse treatment facility

15 2 2

Child and adolescent psychiatry clinic

13 1 5

Public health clinic 11 1 2

Inpatient psychiatric unit 10 1 2

Managed care clinic 9 2 2

Job Corps clinic 8 1 1

Community mental health clinic 5 0 1

STI indicates sexually transmitted infection.

aTime spent is based on sessions per month; 1 session⫽0.5 day.

TABLE 3 Health Professionals Who Regularly Staff the Predominant Site Used in the Adolescent Medicine Block Rotation, as Reported by Adolescent Medicine Faculty Who Are

Responsible for the Block Rotation in Pediatric Residency Programs

Health Professionals % of Programs (N⫽146)

Adolescent medicine specialist

85

Resident/fellow 65

Nurse practitioner 46 Psychiatric or clinical

social worker

40

General pediatrician 37

Dietitian 25

Clinical psychologist 18

Health educator 18

Other 12

Obstetric/gynecologic 10

Psychiatrist 10

Addictions counselor 6

Family physician 3

Adolescent Medicine Training Apart From the Block Rotation Although pediatric residents are ex-pected to have exposure to adolescent medicine throughout their training, the opportunity to care for adoles-cents in continuity clinics is often lim-ited. On the basis of the estimates of residency program directors, in ap-proximately one third of programs, ad-olescents aged 12 through 21 com-priseⱕ10% of the patients seen in the continuity clinic; only rarely do they comprise ⬎25%. In addition, in just more than one third of programs, res-idents reportedly seldom have the op-portunity to see the same adolescent patient for ⱖ2 visits in a given year, whereas only half as many reported that residents often have the opportu-nity to do so.

Residents are also expected to care for adolescents during their inpatient rotations and other subspecialty expe-riences, and, although we have not collected data on their proportion of the patient population, adolescents are generally among the patients whom residents see in these settings. In nearly all pediatric residency pro-grams, adolescents aged 12 to 21 are cared for in pediatric subspecialty clinics; only 2% have an upper age limit for these clinics that is younger than 18. Our findings are similar for pediat-ric inpatient units; however, a some-what smaller proportion of programs include in their general pediatrics clin-ics adolescents who areⱖ18; in fact, patients beyond 11 or 13 years of age are not served by general pediatric clinics in 10% of programs.

The opportunity to do other rotations in areas that are directly related to ad-olescent medicine is also important but rarely required. A rotation in gyne-cology is mandatory in only 3% of

res-psychiatry, rotations are mandatory in

⬃5% of programs but available as an elective in just more than 80%. Rota-tions in school health clinics are re-quired more often—in just fewer than 15% of programs–and are available as an elective in just more than one quar-ter of programs.

DISCUSSION

Our research reveals great variability across pediatric residency programs with respect to ambulatory care train-ing in the care of adolescents and sig-nificant shortcomings in many pro-grams. In most programs, numerous adolescent health topics, particularly those related to mental and behavioral health, are covered only somewhat or not covered at all. Although competen-cies in the care of adolescents with these conditions do not require that every discipline be represented, ade-quate volume and subspecialty exper-tise are more likely to be available when integrated, interdisciplinary ex-pertise is present. Many programs re-ported needing more faculty members from a variety of disciplines, including adolescent medicine, to provide opti-mal training in the care of adolescents. The time spent at many clinical sites during the block rotation is often short, the number of adolescent pa-tients at these sites is often inade-quate, and the predominant training sites are generally not able to provide a comprehensive set of adolescent health care services. Equally impor-tant, although specialty clinic rota-tions provide additional exposure to adolescent patients, continuity clinic experiences often do not afford resi-dents the opportunity to establish on-going, therapeutic relationships with them.

Comparing our findings with a related study by Emans et al16 conducted in

topics in pediatric residency pro-grams has not improved much, if at all. Many of the same topics that report-edly were adequately covered by the vast majority of programs a decade ago seem to be well covered by the same majority today, including normal pubertal growth, sexually transmitted diseases, menstrual problems, contra-ceptives, and interviewing; however, topics that were not characterized as being adequately covered by at least half of training programs a decade ago—violence in relationships, psy-chosomatic complaints, sports medi-cine, chronic illness, and community adolescent health—are topics that still reportedly are not well covered by half of training programs today.

In addition, although the perception that there is a sufficient number of ad-olescent medicine specialists to teach residents has improved, the problem clearly continues in a sizable propor-tion of residency programs. Ten years ago,⬃60% of programs reported an inadequate number of adolescent medicine faculty for teaching “excel-lent” adolescent medicine16; today, just fewer than 30% cite a shortage of ado-lescent medicine specialists. Differ-ences in the way that the question in each survey was worded may account for some of the perceived reduction in adolescent medicine faculty short-ages, yet that so many pediatric resi-dency directors today perceive a shortage of adolescent medicine fac-ulty suggests that there is still a need for teachers in this subspecialty.

reported in our previously published commentary,19three quarters of pedi-atric residency program directors and almost three quarters of adolescent medicine faculty who are responsible for the rotation think that there should be an increase in the availability of 1-year postresidency programs in ad-olescent medicine. Extended clinical experiences would help to ensure a bigger pool of clinicians who are equipped to care for adolescents and supervise residents in caring for rou-tine problems.

Regardless of whether new opportu-nities are available for postresi-dency training in adolescent medi-cine, our research suggests areas in which the quality of the block rota-tion experience for all residents can be improved. It seems that more could be done to ensure that there is a well-defined adolescent medicine rotation curriculum and that resi-dents have concentrated time to train exclusively in adolescent medi-cine, particularly given new work guidelines concerning postcall days at many institutions.20 At the same time, it seems that many programs may need to recruit actively cent patients into hospital adoles-cent clinics by creating a more adolescent-friendly environment and a broader array of services that are responsive to adolescents’ needs. In addition, although there probably is no ideal combination of sites for training in adolescent medicine, problems that pertain to the number and type of sites used for training, the time spent at each, and the ab-sence of appropriate supervising faculty need to be reviewed and ad-dressed at many institutions.

Moreover, there are important ways in which pediatric residency training can be restructured to ensure that resi-dents have adequate exposure to the health care needs of adolescents

throughout their training. As noted by many residency program directors who responded to our open-ended questions, the continuity clinic could afford residents increased opportuni-ties in longitudinal care for adoles-cents if adolescent-specific clinic sites and community practices with adoles-cent expertise were included as op-tional placements or if more adoles-cents were recruited into pediatric clinics; however, few respondents ad-dressed residents’ total experience with adolescents, including intensive care and inpatient and outpatient set-tings. All of these places are potential sites for residents to achieve knowl-edge and skills in adolescent medicine. Although training environments are important, a comprehensive look at all adolescent health competencies across pediatric residency experi-ences might result in greater long-term change in the care that is avail-able to youth. In ambulatory care training, minimum requirements for patient-centered adolescent care ex-periences included in each resident’s clinic experience could be established. Faculty in continuity clinics could be expanded to include not only adoles-cent medicine specialists but also pe-diatricians who are expert in the care of adolescents and also psychiatrists and other health care professionals who are able to provide supervision in the management of common mental health and substance abuse problems and in experience with team-based care. Furthermore, to provide resi-dents regular interaction with clinical faculty who are skilled in the care of adolescents, adolescent medicine spe-cialists, and others who are skilled in the care of adolescents could partici-pate as faculty for general and special pediatric clinics.

Renewed attention should be given to articulating the core competencies that are needed to care for

adoles-cents and improve their health out-comes. A framework of competencies for each aspect of adolescent medi-cine would foster an integrated curric-ulum across all rotations and clinics in addition to the specialized block rota-tion. Given that adolescents are seen in large numbers in almost all commu-nity practices, all pediatric residency programs need to ensure that resi-dents acquire basic core competen-cies in adolescent medicine. Some residents, however, may anticipate es-tablishing practices in which a large proportion of their patients will be ad-olescents. For this subset of residents, perhaps certain residency programs could offer a more enriched adoles-cent medicine curriculum as a special-ized track, establishing themselves as centers of excellence, and an ex-panded set of competencies could be established for this purpose. Move-ment toward adolescent medicine am-bulatory care training that is outcome-based rather than process-outcome-based will need to occur within a broad-scale ex-amination of the entire residency.

Our study is limited in several ways. Adolescent training may be better and, thus, more salient to those who re-sponded. Alternatively, respondents may have been more aware of the need for those services in their programs. Specific items may not have been un-derstood consistently by different pro-gram directors. We did not fully ex-plore the integration of adolescent issues into ambulatory and inpatient experiences throughout the 3 years of training, instead focusing on the am-bulatory setting, because it has tradi-tionally been underemphasized in pe-diatric training. In addition, we made no attempt to establish the validity of the program director’s self-reported responses, and the reported experi-ences may not reflect the actual train-ing received by residents in a particu-lar program.

Significant variation and gaps persist in adolescent medicine training in pe-diatric residency training throughout the United States. This affects cover-age of required topics that are impor-tant to adolescent health care, the availability of faculty to teach adoles-cent medicine, and the ambulatory care training experience during and outside of the 1-month mandatory ad-olescent medicine rotation. Improving pediatric residency training will re-quire a greater program commitment

ganizations, and professional associa-tions. Implementing reforms carries a cost, but there is also a cost for not having future pediatricians adequately trained in the care of our nation’s adolescents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr James Stockman, Presi-dent of the American Board of Pediat-rics, for helpful perspectives and ad-vice throughout the progress of this project. We also gratefully

acknowl-the University of Michigan. In addition, we express our appreciation to the As-sociation for Pediatric Residency Pro-gram Directors for assisting us in ob-taining our high response rate and to all of the pediatric residency program directors and adolescent medicine faculty who responded to our 2 sur-veys. Finally, we acknowledge the gen-erous contributions made by several family foundations and individuals who saw the importance of this work and were willing to support us.

REFERENCES

1. Forhan SE. Prevalence of sexually transmit-ted infections and bacterial vaginosis among female adolescents in the United States. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2003–2004 CDC Teleconference; March 11, 2008

2. US Department of Health and Human Ser-vices.Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General, US Public Health Service; 1999 3. Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Johnson

CL. Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents: 1999 –2002.JAMA.2002;288(14):1728 –1732

4. Knopf D, Park MH, Mulye TP.The Mental Health of Adolescents: A National Profile, 2008. San Francisco, CA: National Adoles-cent Health Information Center; 2008

5. Freed GL; Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of Pediatrics. Compar-ing perceptions of trainCompar-ing for medicine-pediatrics and categorically trained physi-cians.Pediatrics.2006;118(3):1104 –1108 6. American Academy of Pediatrics, Division

of Health Policy Research.Periodic Survey of Fellows #42: Providing Health Care to Adolescents—Pediatricians Attitudes and Practices. Elk Grove, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 1999. Available at: www.aap.org/research/periodicsurvey/ summaryoffindings.htm. Accessed Novem-ber 2007

7. Hellerstedt WL, Smith QE, Shew ML, Resnick MD. Perceived knowledge and training needs in adolescent pregnancy prevention: results from a multidisciplinary survey.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2000;154(7):679 – 684

8. Williams J, Klinepeter K, Palmes G, Foy JM. Diagnosis and treatment of behavioral health disorders in pediatric practice. Pedi-atrics.2004;114(3):601– 606

9. Frankenfield DL, Keyl PM, Gielen A, Wissow LS, Werthamer L, Baker SP. Adolescent patients: healthy or hurting? Missed oppor-tunities to screen for suicide risk in the pri-mary care setting. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2000;154(2):162–168

10. Borowsky IW, Ireland M. National survey of pediatricians’ violence prevention coun-seling. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999; 153(11):1170 –1176

11. Van Hook S, Harris SK, Brooks T, et al. The “Six T’s”: barriers to screening teens for substance abuse in primary care.J Adolesc Health.2007;40(5):456 – 461

12. Kaplan CP, Perez-Stable EJ, Fuentes-Afflick E, et al. Smoking cessation counseling with young patients: the practices of family phy-sicians and pediatricians.Arch Pediatr Ado-lesc Med.2004;158(1):83–90

13. Freed GL, Nahra TA, Wheeler JR. Which phy-sicians are providing health care to Ameri-ca’s children: trends and changes during the past 20 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2004;158(1):22–26

14. Phillips RL Jr, Dodoo MS, McCann JL, et al.

Report to the Task Force on the Care of

Chil-dren by Family Physicians. Washington, DC: Robert Graham Center; 2005

15. Beatty A, Chalk R.A Study of Interactions: Emerging Issues in the Science of

Adoles-cence. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006

16. Emans SJ, Bravender T, Knight J, et al. Ado-lescent medicine training in pediatric resi-dency programs: are we doing a good job?

Pediatrics.1998;102(3 pt 1):588 –595

17. American Medical Association.Graduate Medical Education Directory, 1997–1998.

Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 1998

18. American Board of Pediatrics.The Petition to the American Board of Medical Subspe-cialties (ABMS) for Subcertification in Ado-lescent Medicine by the American Board of Pediatrics. Chapel Hill, NC: American Board of Pediatrics; Submitted to the ABMS on January 23, 1990 and approved in March 1991

19. Fox HB, McManus MA, Diaz A, et al. Advancing medical education training in adolescent health.Pediatrics.2008;121(5):1043–1045

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-3740 originally published online December 7, 2009;

2010;125;165

Pediatrics

Wilson

Elster, Marianne E. Felice, David W. Kaplan, Charles J. Wibbelsman and Jane E.

Harriette B. Fox, Margaret A. McManus, Jonathan D. Klein, Angela Diaz, Arthur B.

Adolescent Medicine Training in Pediatric Residency Programs

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/165

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/165#BIBL

This article cites 11 articles, 4 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

icine_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/adolescent_health:med

Adolescent Health/Medicine following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-3740 originally published online December 7, 2009;

2010;125;165

Pediatrics

Wilson

Elster, Marianne E. Felice, David W. Kaplan, Charles J. Wibbelsman and Jane E.

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/165

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.