META-ANALYSIS: BACTERIAL MENINGITIS IN CHILDREN WITH

A FIRST FEBRILE SEIZURE

Dr. Ziyad Faleh Alnofei1*, Homam Talal Abdullah Alsharif2, Sarah Obaid Dhafar3, Saad Mohamed Saad Alharthi4, Sultan Mohammed Saleh Alzahrani5, Emad Marzouq

Rashed Alsufyani6, Amal Saleh hamdi Alsofyany7, Abdulaziz Saeed Asiri8 and Rayan Khalid Almalki9

1*

General Pead. Consultant Ta’if Children Hospital, Ta’if, Saudi Arabia.

2,3,5,6,7,8,9,

Medical Intern, Al-Hada Armed Forces Hospital, Taif, Saudi Arabia.

4

Medical Student, Al-Hada Armed Forces Hospital, Taif, Saudi Arabia.

ABSTRACT

Background & Purpose: Seizures may be the sole presentation of

bacterial meningitis in febrile babies. Seizures are the primary

manifestation of meningitis in 16.7% of kids and in one-third of those

sufferers, whereas meningeal signs and signs might not be obvious.

Consequently, it is obligatory to exclude underlying meningitis in kids

providing with fever and seizure previous to making the analysis of FS.

The Aim of this work is to provide cumulative data about the

prevalence of Bacterial Meningitis (BM) among children with a first

seizure in the context of fever. Methods: A systematic search was

performed of PubMed, Cochrane library Ovid, Scopus & Google scholar to identify

Pediatrics clinical trials, and prevalence studies, which studied the outcome of the prevalence

of BM in young children presenting to emergency care with a first ‘‘seizure and fever’’. A

meta-analysis was done using fixed and random-effect methods. The primary outcome was

prevalence of BM. Secondary outcomes were prevalence of encephalitis and overall

prevalence of CNS infections. Results: A total of 7 studies were identified involving 1414

patients. Regarding primary outcome measures, I2 (inconsistency) was 84% with highly

significant Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0.01), so random-effects model was carried out; with

overall pooled prevalence of Bacterial Meningitis = 2% (95% CI 0.5 to 4.4). Regarding

secondary outcome measures, I2 (inconsistency) was 86% with highly significant Q test for

heterogeneity (p < 0.01), so random-effects model was carried out; with overall pooled Article Received on

21 Oct. 2019,

Revised on 11 Nov. 2019, Accepted on 01 Dec. 2019,

DOI: 10.20959/wjpr201913-16435

*Corresponding Author

Dr. Ziyad Faleh Alnofei

General Pead. Consultant Ta’if Children Hospital, Ta’if, Saudi Arabia.

prevalence of encephalitis = 0.8% (95% CI to 3.6). I2 (inconsistency) was 95% with highly

significant Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0.01), so random- effects model was carried out; with

overall pooled prevalence of overall CNS infections = 4.2% (95% CI 0.12 to 13.5).

Conclusion: To conclude, Meningitis is more common in patients less than 18 months

presenting with febrile seizures.

KEYWORDS: Bacterial Meningitis, Children, First Febrile Seizure.

INTRODUCTION

Febrile seizures affect 2% to 5% of children in Europe and North the united states. it is defined

as a seizure taking place in children aged 6 months to 5 years, in a context of fever, without a

history of an unprovoked seizure or concurrent central nervous system infection.[1]

Most febrile seizures are precipitated through fevers from viral upper respiratory infections,

ear infections, or roseola. but, meningitis, if bacterial in etiology, also can present with fever

and a single, self-limited seizure. therefore it is a priority to diagnose or exclude bacterial

meningitis.[2]

Febrile seizures are classified into simple and complex febrile seizures. Simple febrile seizures

are defined as generalized seizures occurring only once in a 24-hour duration and lasting less

than 15 mins. Whereas, complex/extraordinary febrile seizures are defined as focal seizures,

lasting more than 15 mins and occurring more than one time in 24 hours. Simple febrile

seizures are benign and self-restricting. They have higher diagnosis and carry very low threat

for further epilepsy. Probability of acute bacterial meningitis presenting as fever with seizures

varies from 0.6 % to 6.7 %.[3]

Seizures may be the sole presentation of bacterial meningitis in febrile babies. Seizures are

the primary manifestation of meningitis in 16.7% of kids and in one-third of those sufferers,

whereas meningeal signs and signs might not be obvious. Consequently, it is obligatory to

exclude underlying meningitis in kids providing with fever and seizure previous to making

the analysis of FS.[4]

The American Academy of Pediatrics in its consensus statement strongly recommends

performing lumbar puncture in infants elderly 6-365 days, and considering it in youngsters

aged 12-18 months, who manifest first simple febrile seizures, for the sake of diagnosing

observed. Recent studies demonstrate a variable prevalence of meningitis in patients with

first febrile seizures.[5]

Aim of the study: The Aim of this work is to provide cumulative data about the prevalence of Bacterial Meningitis (BM) among children with a first seizure in the context of fever.

METHODS

This review was carried out using the standard methods mentioned within the Cochrane

handbook and in accordance with the (PRISMA) statement guidelines.[6]

Identification of studies

An initial search carried out throughout the PubMed, Cochrane library Ovid, Scopus &

Google scholar using the following keywords: Bacterial Meningitis, Children, First

Febrile Seizure.

We will consider published, full text studies in English only. Moreover, no attempts were

made to locate any unpublished studies nor non-English studies.

Criteria of accepted studies

Types of studies

The review will be restricted to clinical trials, and prevalence studies, either prospective or

retrospective, which studied the outcome of A the prevalence of BM in young children

presenting to emergency care with a first ‘‘seizure and fever’’.

Types of participants

Participants will be children from 6 to 72 months.

Types of outcome measures

1. Prevalence of BM (1ry outcome)

2. Prevalence of encephalitis (2ry outcome)

3. Prevalence of overall CNS infections (2ry outcome)

Inclusion criteria

English literature.

Journal articles.

Between 2009 until 2019.

seizure in the context of fever.

Human studies.

Exclusion criteria

Articles less than 20 patients, because the likelihood that small studies would have

overestimated event outcome rates.

Irrelevance to our study.

Methods of the review

Locating studies

Abstracts of articles identified using the above search strategy will be viewed, and articles

that appear of fulfill our inclusion criteria will be retrieved in full, when there is a doubt, a

second reviewer will assess the article and consensus will be reached.

Data extraction

Using the following keywords: Bacterial Meningitis, Children, First Febrile Seizure, data will

be independently extracted by two reviewers and cross-checked.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis done using MedCalc ver. 18.11.3 (MedCalc, Ostend, Belgium). Data were

pooled and odds ratios (ORs) as well as standard mean differences (SMD), were calculated

with their 95 per cent confidence intervals (CI). A meta-analysis was performed to calculate

direct estimates of each treatment, technique or outcome. According to heterogeneity across

trials using the I2-statistics; a fixed-effect model (P ≥ 0.1) or random-effects model (P < 0.1)

was used.

Study selection

We found 68 records; 31 were excluded based on title and abstract review; 37 articles are

searched for eligibility by full text review; 11 articles cannot be accessed or obtain full text;

10 studies were reviews and case reports; 9 were not describing outcome; leaving 7 studies

Figure 1: Flow chart for study selection.

RESULTS

[image:5.595.128.523.441.572.2]Descriptive analysis of all studies included (Tables 1, 2) Table 1: Patients and study characteristics.

N Author Study setting Number of patients Age

(months) Total

1 Shaked et al., 2009 ED 56 9

2 Seltz et al., 2009 ED, inpatient 192 19

3 Kimia et al., 2010 ED 526 17

4 Guedj et al., 2015 ED 168 8

5 Siddiqui et al., 2017 ED 157 18.5

6 Sohail et al., 2018 Inpatient 165 8

7 Sivalingam et al., 2019 Inpatient 150 30

#Studies were arranged according to publication year. ED: emergency department.

Table 2: Summary of outcome measures in all studies.

N Author

Primary outcome Secondary outcomes

Prevalence of BM Prevalence of encephalitis

Prevalence of overall CNS infections

1 Shaked et al., 2009 0 0 0

2 Seltz et al., 2009 1 0 1

3 Kimia et al., 2010 3 0 15

4 Guedj et al., 2015 0 --- ---

5 Siddiqui et al., 2017 12 --- ---

6 Sohail et al., 2018 5 --- ---

[image:5.595.17.579.625.773.2]The included studies published between 2009 and 2019.

Regarding patients’ characteristics, the average age of all patients was (15 months). The total

number of patients in all the included studies was 1414 patients.

Meta-analysis of outcome measures

Meta-analysis study was done on 7 studies which described an overall number of patients

(N=1414).

Patients who achieved outcome measures were pooled:

Each outcome was measured by

Pooled Prevalence (Proportion)

Prevalence of BM (1ry outcome)

Prevalence of encephalitis (2ry outcome)

Prevalence of overall CNS infections (2ry outcome) Regarding primary outcome measure,

We found 7 studies reported Bacterial Meningitis with total number of patients (N=1414).

I2 (inconsistency) was 84% with highly significant Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0.01), so

random-effects model was carried out; with overall pooled prevalence of Bacterial Meningitis

[image:6.595.96.492.487.734.2]= 2% (95% CI 0.5 to 4.4).

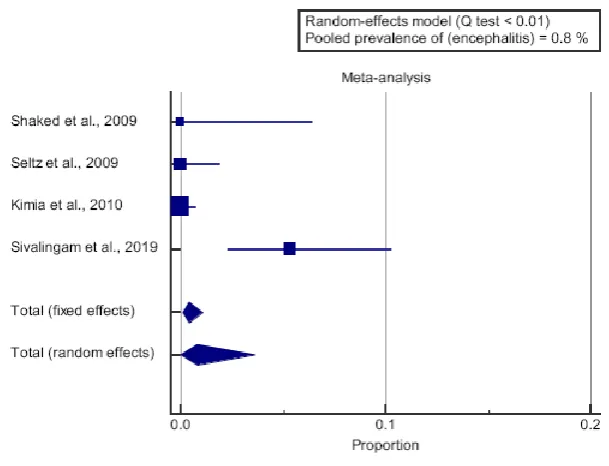

Regarding secondary outcome measure,

We found 4 studies reported encephalitis with total number of patients (N=924).

I2 (inconsistency) was 86% with highly significant Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0.01), so

[image:7.595.144.449.198.431.2]random-effects model was carried out; with overall pooled prevalence of encephalitis = 0.8%.

Figure 3: Forest plot of (encephalitis) - Proportion.

We found 4 studies reported overall CNS infections with total number of patients (N=924).

I2 (inconsistency) was 95% with highly significant Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0.01), so

random-effects model was carried out; with overall pooled prevalence of overall CNS

infections = 4.2% (95% CI 0.12 to 13.5).

[image:7.595.151.448.582.745.2]DISCUSSION

The Aim of this work is to provide cumulative data about the prevalence of Bacterial

Meningitis (BM) among children with a first seizure in the context of fever.

The included studies published between 2009 and 2019.

Regarding patients’ characteristics, the average age of all patients was (15 months). The total

number of patients in all the included studies was 1414 patients.

Regarding Meta-analysis of outcome measures; Meta-analysis study was done on 7 studies

which described an overall number of patients (N=1414).

Regarding primary outcome measure; We found 7 studies reported Bacterial Meningitis with

total number of patients (N=1414).

I2 (inconsistency) was 84% with highly significant Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0.01), so

random-effects model was carried out; with overall pooled prevalence of Bacterial Meningitis

= 2% (95% CI 0.5 to 4.4) which came in agreement with Khosroshahi et al. 2016[2] and with

Batra et al. 2011[5] and with Najaf-Zadeh et al. 2013[7] and disagreement with Reddy, Khan,

and Hegde 2016.[8]

Khosroshahi et al. 2016[2] reported that Bacterial meningitis was evident in 1.1% of patients

with first febrile seizures. 80 % of children with bacterial meningitis were presented with

complex febrile seizures with focal features. Another risk factor predicting bacterial

meningitis became duration of postictal drowsiness.

Batra et al. 2011[5] reported that the prevalence of meningitis was 2.4% in children with first

febrile seizures, 0.86% in simple febrile seizures, and 4.81% in complex febrile seizures.

Najaf-Zadeh et al. 2013[7] reported that the pooled prevalence of BM using a random effects

model was 2.6% (95%).

Reddy, Khan, and Hegde 2016[8] reported that The CSF analysis turned into normal in all the

kids who presented as simple febrile seizures. There has been 25.87% prevalence of

meningitis in children with extraordinary febrile seizures who underwent lumbar puncture.

The CSF yield suggestive of bacterial meningitis turned into as excessive as 50% in children

Regarding secondary outcome measure; We found 4 studies reported encephalitis with total

number of patients (N=924).

I2 (inconsistency) was 86% with highly significant Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0.01), so

random-effects model was carried out; with overall pooled prevalence of encephalitis = 0.8%

(95% CI 0.01 to 3.6) which came in disagreement with (Casasoprana et al. 2013)[9] and with

Guedj et al. 2017.[10]

(Casasoprana et al. 2013)[9] Reported that the diagnosis of meningitis/encephalitis become

selected in 8 cases: 3 instances of viral meningitis, three bacterial meningitis (Streptococcus

pneumoniae), and non-herpetic viral encephalitis. The prevalence of bacterial meningitis in

our study changed into 1.9%. The risk of significant infection, bacterial meningitis or

encephalitis, become expanded while there has been a complex FS (14% as opposed to 0%

with a simple FS, P=0.06). The presence of other suggestive clinical symptoms become

strongly related to a risk of bacterial meningitis/encephalitis (36% in case of scientific

orientation versus 0% within the absence of such signs, P<0.001).

Guedj et al. 2017[10] Reported that The proportions of children who underwent a lumbar

puncture amongst those with and without a medical examination end result suggestive of

meningitis or encephalitis were, respectively, 54% (113/209) and 23% (147/630).

We found 4 studies reported overall CNS infections with total number of patients (N=924).

I2 (inconsistency) was 95% with highly significant Q test for heterogeneity (p < 0.01), so

random-effects model was carried out; with overall pooled prevalence of overall CNS

infections = 4.2 % (95% CI 0.12 to 13.5) which came in agreement with Najaf-Zadeh et al.

2013[7] and with Mwipopo et al. 2016[11] and disagreement with Mahmood, Fareed, and

Tabbasum 2011.[12]

Najaf-Zadeh et al. 2013[7] Reported that the overall average prevalence of CNS infections was

3.9% (range 2.3 to 7.4%).

Mwipopo et al. 2016[11] reported that There were 109 (54.5%) males and 91 (45.5%) females.

among these patients, 193 (96.5%) were aged 1 month to 5 years and 182 (91.0%) presented

with seizures and fever. Generalized tonic-clonic seizure become the maximum common

175 (87.5%) children followed by epilepsy in 11 (5.5%) children. There were simplest three

(2%) kids with central nervous system infections.

Mahmood, Fareed, and Tabbasum 2011[12] reported that The most common cause of fever

leading to febrile convulsions was respiratory tract infections 40%, 2nd most common being

UTI that accounts for 24%, CNS infections being 8% and other causes 24%.

CONCLUSION

To conclude, Meningitis is more common in patients less than 18 months presenting with

febrile seizures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Conflict of interest

None.

Authorship

All the listed authors contributed significantly to conception and design of study, acquisition,

analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of manuscript, to justify authorship.

Funding Self-funding.

REFERENCES

1. Guedj, R.; Chappuy, H.; Titomanlio, L.; Trieu, T.-V.; Biscardi, S.; Nissack-Obiketeki, G.;

Pellegrino, B.; Charara, O.; Angoulvant, F.; Villemeur, T. B. D.; et al. Risk of Bacterial

Meningitis in Children 6 to 11 Months of Age With a First Simple Febrile Seizure: A

Retrospective, Cross-Sectional, Observational Study. Acad Emerg Med, 2015; 22(11):

1290–1297. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12798.

2. Khosroshahi, N.; Kamrani, K.; Zoham, M. H.; Noursadeghi, H. Factors Predicting

Bacterial Meningitis in Children Aged 6-18 Months Presenting with First Febrile Seizure;

2016. https://doi.org/10.18203/2349-3291.ijcp20161033.

3. Reddy, D. S. S.; Khan, S. H.; Hegde, P. Predictors of Meningitis in Children Presenting

with First Episode of Febrile Seizure; 2016.

https://doi.org/10.18203/2349-3291.ijcp20164593.

4. Tavasoli, A.; Afsharkhas, L.; Edraki, A. Frequency of Meningitis in Children Presenting

neurology, 2014; 8(4): 51.

5. Batra, P.; Gupta, S.; Gomber, S.; Saha, A. Predictors of Meningitis in Children Presenting

With First Febrile Seizures. Pediatric Neurology, 2011; 44(1): 35–39.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2010.07.005.

6. Liberati, A.; Altman, D.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.; Ioannidis, J.; Clarke, M.;

Devereaux, P.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic

Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Healthcare Interventions. Bmj

2009; 339.

7. Najaf-Zadeh, A.; Dubos, F.; Hue, V.; Pruvost, I.; Bennour, A.; Martinot, A. Risk of

Bacterial Meningitis in Young Children with a First Seizure in the Context of Fever: A

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE, 2013; 8(1): e55270.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055270.

8. Reddy, D. S. S.; Khan, S. H.; Hegde, P. Predictors of Meningitis in Children Presenting

with First Episode of Febrile Seizure; 2016.

https://doi.org/10.18203/2349-3291.ijcp20164593.

9. Casasoprana, A.; Hachon, C. L. C.; Claudet, I.; Grouteau, E.; Chaix, Y.; Cances, C.;

Karsenty, C.; Cheuret, E. [Value of lumbar puncture after a first febrile seizure in children

aged less than 18 months. A retrospective study of 157 cases]. Arch Pediatr, 2013; 20(6):

594–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcped.2013.03.022.

10.Guedj, R.; Chappuy, H.; Titomanlio, L.; De Pontual, L.; Biscardi, S.; Nissack-Obiketeki,

G.; Pellegrino, B.; Charara, O.; Angoulvant, F.; Denis, J.; et al. Do All Children Who

Present With a Complex Febrile Seizure Need a Lumbar Puncture? Annals of Emergency

Medicine, 2017; 70(1): 52-62.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.11.024.

11.Mwipopo, E. E.; Akhatar, S.; Fan, P.; Zhao, D. Profile and Clinical Characterization of

Seizures in Hospitalized Children. Pan Afr Med J, 2016; 24.

https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2016.24.313.9275.

12.Mahmood, K. T.; Fareed, T.; Tabbasum, R. Management of Febrile Seizures in Children;

2011.

Papers included in our meta-analysis

Shaked, O., Peña, B.M.G., Linares, M.Y. and Baker, R.L., Simple febrile seizures: are the

AAP guidelines regarding lumbar puncture being followed?. Pediatric emergency care,

2009; 25(1): 8-11.

meningitis/encephalitis in children with complex febrile seizures. Pediatric emergency

care, 2009; 25(8): 494-497.

Kimia, A., Ben-Joseph, E.P., Rudloe, T., Capraro, A., Sarco, D., Hummel, D., Johnston,

P. and Harper, M.B., Yield of lumbar puncture among children who present with their

first complex febrile seizure. Pediatrics, 2010; 126(1): 62-69.

Guedj, R., Chappuy, H., Titomanlio, L., Trieu, T.V., Biscardi, S., Nissack-Obiketeki, G.,

Pellegrino, B., Charara, O., Angoulvant, F., Villemeur, T.B.D. and Levy, C., Risk of

Bacterial Meningitis in Children 6 to 11 Months of Age with a First Simple Febrile

Seizure: A Retrospective, Cross-sectional, Observational Study. Academic Emergency

Medicine, 2015; 22(11): 1290-1297.

Siddiqui, H.B., Haider, N. and Khan, Z., Frequency of acute bacterial meningitis in

children with first episode of febrile seizures. JPMA. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical

Association, 2017; 67(7): 1054-1058.

Sohail, A., Das, C., Parkash, J. and Hotwani, P., Association of Meningitis among

Children with First Attack of Fever and Seizure without Clinical Manifestations of

Meningitis. Journal of Liaquat University of Medical & Health Sciences, 2018; 17(04):

241-244.

Sivalingam, B., Srinivasan, R. and Thilak, T., Clinicoetiological Profile Of First Episode

Seizure In Children 1 Month To 12 Years. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental