INFORMATION SEEKING BEHAVIOUR AMONG HEALTH PROFESSIONALS IN PUBLIC HEALTH FACILITIES IN GARISSA

COUNTY, KENYA

LANGAT KIPKOECH MILTON (BSc.) Q141/CTY/PT/21177/2012

A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF SCIENCE IN HEALTH INFORMATION MANAGEMENT IN THE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH OF KENYATTA UNIVERSITY.

ii

DEDICATION

iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I wish to extend my deep gratitude to Dr. G. Otieno and Dr. A. Yitambe, my research supervisors, for their exemplary guidance and constant encouragement throughout the course of this research thesis.

I am grateful to Department of Health Management and Informatics, School of Public Health and the entire Kenyatta University for the opportunity and supported offered to successfully undertake this course.

I also take this opportunity to thank the Health Management Team (Dr.Diney, Mr.Daud, Mr. Abdirashid, Mr.Chege and Mr.Gonjobe) of Lagdera Sub-County for their cordial support and valuable information which helped me in completing this research thesis.

Last but not least, I wish to express my gratitude to almighty God, my wife- Caroline Barue, members of my family and friends for their unwavering material, moral and spiritual support without which this research thesis would not have been possible. .

I am also thankful to all those who participated both directly and indirectly in the completion of this thesis.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DECLARATION ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

DEDICATION ... ii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ... iii

LIST OF TABLES ... vii

LIST OF FIGURES ... viii

DEFINITION OF TERMS ... ix

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ... xii

ABSTRACT ... xiii

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1 Background Information ... 1

1.2 Statement of the Problem ... 2

1.3 Justification for the Study ... 3

1.4 Research Questions ... 3

1.5 Objectives... 4

1.6 Null Hypothesis ... 5

1.7 Significance of the Study ... 5

1.8 Scope and Delimitation ... 5

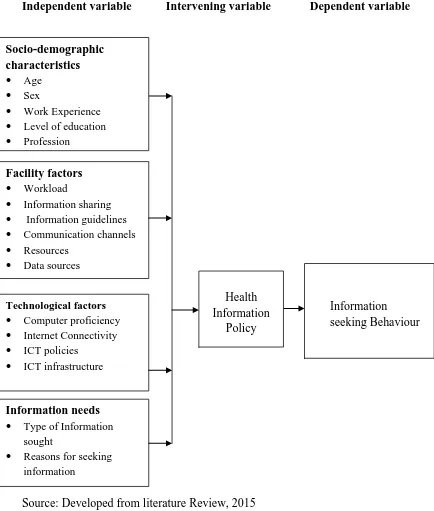

1.9 Conceptual Framework ... 6

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW ... 8

2.1 Information Needs and Seeking Behaviour ... 8

2.2 Institutional Factors ... 10

2.3 Technological Factors... 11

2.4 Socio-Demographic Factors ... 14

v

CHAPTER THREE: MATERIALS AND METHODS ... 16

3.1 Study Design ... 16

3.2 Study Variables ... 16

3.3. Location of the Study ... 17

3.4 Study Population ... 18

3.5 Sampling Technique ... 19

3.6 Sample Size Determination ... 20

3.7 Data Collection Tools ... 21

3.8 Data Collection Procedures ... 22

3.9 Pre-testing of Data Collection Tools ... 23

3.10 Reliability of Study Tools ... 23

3.11 Validity of Study Tools ... 23

3.12 Data Analysis ... 24

3.13 Ethical Considerations ... 24

CHAPTER FOUR: RESULTS ... 26

4.1 Background Characteristics of Respondents ... 26

4.2 Health Information Needs ... 27

4.3 Information Seeking Behaviour ... 31

4.4 Socio-Demographic Factors ... 33

4.5 Facility factors ... 40

4.6 Technological factors ... 46

CHAPTER FIVE: DISCUSSION, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ... 57

5.1 Discussion... 57

5.2 Conclusions ... 66

5.3 Recommendations for Policy ... 67

5.4 Recommendations for Further Study ... 68

vi

APPENDICES ... 73

Appendix 1: Survey Questionnaire ... 73

Appendix 2: Key Informant Interview Guide ... 78

Appendix 3: Focus Group Discussion Guide ... 79

Appendix 4a:List of Health Facilities and Number of Health Professionals ... 80

Appendix 4b: List of Health Facilities and Number of Health Professionals ... 81

Appendix 5: Introduction letter from Department of HMI ... 82

Appendix 6: Introduction Letter from Ministry of Health, Garissa County ... 83

Appendix 7: Approval of Research proposal from Graduate School, KU ... 84

vii

LIST OF TABLES

Table 3.2: Study respondents distribution ... 21

Table 4.1: Age, gender ,education level, profession and work experience of respondents ... 26

Table 4.2: Frequency of using information resources ... 33

Table 4.3: Influence of age and gender on information seeking behaviour ... 34

Table 4.4: Influence of education and profession on information seeking behaviour . 36 Table 4.5: Influence of work experience on information seeking behaviour ... 38

Table 4.6: Workload, information sharing and information guidelines ... 40

Table 4.7: Form of data storage and fund allocation ... 41

Table 4.8 Influence of workload and information sharing on ISB of HPs ... 43

Table 4.9 Influence of form of data storage on information seeking behavior ... 45

Table 4.10: Computer proficiency and ICT skills ... 47

Table 4.11: ICT policy, internet connectivity and adequacy of functional ICT tools . 48 Table 4.12: Influence of Computer literacy and ICT skills on information seeking behaviour... 49

Table 4.13: Influence of ability to save downloads and analyze digital data on information seeking behaviour ... 51

Table 4.14: Influence of data interpretation and sending ability on information seeking behaviour... 53

viii

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1.1: Conceptual framework ... 7

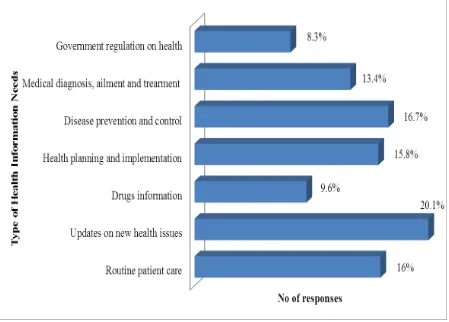

Figure 4.1 Type of health information sought ... 28

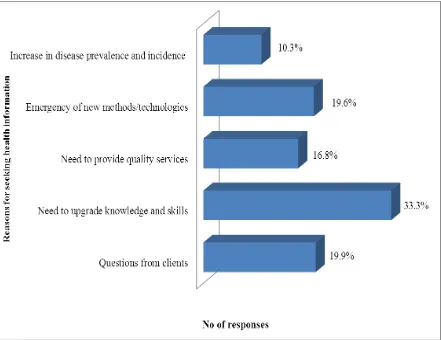

Figure 4.2 Reasons for seeking health information ... 29

Figure 4.3 How health professionals seek health information ... 30

Figure 4.4: Type of information resources used ... 31

ix

DEFINITION OF TERMS

Communication channel This is the means used to pass health information among health professionals in a health facility.

Computer Proficiency Refers to ability of health professionals to use basic Microsoft office applications in utilizing information

Data sources It refers to sources used by health professionals to obtain health data in the health facility

Health information Is processed health data needed for delivery of health services by health professionals

Health Professionals This refers to all health personnel with formal training working at the selected Public health facilities.

ICT infrastructure Refers to hardware and software that supports the flow and processing of information in a health facility.

ICT policies It refers to a set of principles and guidelines that outline how ICT strategy will be put into operation in health facilities

Informal Resources These are human resources which includes: colleagues, supervisors and senior staff

x

Information need Refers to the recognition by health professionals of their own deficits and identification of what they consider useful to improve their health services delivery.

Information seeking behaviour

This refers to the variety of health information resources employed by health professional to access health

information they need. Different health professionals may use different information resources to access health information in order to meet their health information needs. This variable will be measured by the frequency of utilization of different Health information resources by health professionals to access health information.

Internet connectivity This refers to availability of internet network and the way it is accessed by health professional in the health facility

Organizational culture Refers to guidelines/norms that govern health information access and exchange among health professionals in the health facility

Public Health Facilities It refers to Sub-County Hospitals, Health Facilities and Dispensaries that are owned by Government of Kenya. Resources It refers to financial allocations meant for addressing

xi

xii

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

AIDS Acquired Immune deficiency Syndrome CPD Continuous Professional Development CRA Commission on Revenue Allocation FGD Focus Group Discussion

HCP Health Care Professionals HI Health Information

HIRs Health Information Resources HIV Human Immune Virus

HPs Health Professionals

HR Human Resource

ICT Information and Communication Technology KII Key Informant interview

SARS Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

SCHRIO Sub-County Health Records and Information Officer SCMOH Sub-County Medical Officer of Health

SCPHN Sub-County Public Health Nurse SCPHO Sub-County Public Health Officer SOPs Standard Operating Procedures

SPSS Statistical package for the Social Science

US United States

xiii ABSTRACT

1

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background Information

Information is inevitable in the health profession. The need to become informed and knowledgeable individuals is important among qualified health care professionals (HCPs) who have vital roles in achieving health goals of a given country (Pakenham-Walsh & Bukachi, 2009). Updating knowledge with relevant information is very important for health care professionals to deliver quality and sustainable health care services to their consumers. This is possible only when there is a sustainable access to information resources (HIRs) in health facilities (Ghebre, 2005).

Information is important to improve knowledge based on which evidence-based decision is made to serve the clients of health facilities. Access to information facilitates the use of new medical technologies, proper handling of the necessary medical procedures and treatment of patients. Proper information management brings health workers to act harmoniously in a similar manner on medical and health practice (Dubow & Chetley, 2011). Information needs and seeking behaviour varies among HPs working in rural and urban areas due limited access to information outlets (Mohamed, 2009). Internet use, access to library, provision of training on use of audios and videos displays were the main means used to provide information to the users (Garcia, 2010).

2

acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Asian bird flu, HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis. It was also due to the increasing concern of bioterrorism (spreading anthrax spores via the US Postal Service in 2001) (LaPelle et al, 2006). Currently, resource limited countries face several health challenges that threaten the lives of millions of people (Ojo, 2006).

Lack of information communication creates such situations that produce medical errors, which are common in health facilities. This situation has the potential to cause miss-diagnosis, wrong treatment, increase multi drug resistance, severe injury and unexpected patients death (Dubow & Chetley, 2011). Studies in developing Countries such as Kenya have revealed that several factors such as cost, past success, accuracy, reliability, comprehensiveness, usefulness, currency, response time, accessibility, technical quality, and format influence information seeking behaviour of health professionals (Davies, 2007).

1.2 Statement of the Problem

3

appropriate and reliable HI updates in health care. This could be worse in marginalized regions such as Garrisa County, ranked as one of the top ten marginalized areas in Kenya, which infrastructural and resource challenges which affects access to HI (Marginalized Survey Report, 2010). According to Gatero (2011), understanding information seeking behaviour of health professionals is the only realistic strategy for addressing their HI needs. Therefore, this aimed to assess information seeking behaviour among health professionals in Garissa County.

1.3 Justification for the Study

This study was conducted in Garissa County, because it is one of the marginalized areas in Kenya. In these areas, the information needs of health professionals working in marginalized areas have been given little attention which underpins the need for this study. In addition, no known study was documented on information seeking behaviour in the study area. In developing countries, of which Kenya is included, healthcare workers at all levels of service delivery have substantial needs for information which is very important in delivering of quality and sustainable health care services to their clients. Therefore, understanding the information seeking behaviour of health professionals is a prerequisite to meeting their information needs (Mohamed, 2011).

1.4 Research Questions

4

2. What are the socio-demographic characteristics of health professionals associated with information seeking behaviour in public health facilities in Garissa County?

3 . How do facility factors influence information seeking behaviour of health professionals in public health facilities in Garissa County?

4. What are the technological factors influencing information seeking behaviour of health professionals in public health facilities in Garissa County?

1.5 Objectives

1.5.1 Broad Objectives

The main research objective for this study was to assess information seeking behaviour of health professionals in public health facilities in Garrisa County.

1.5.2 Specific Objectives

The study had five specific objectives, namely:

1. To establish health information needs of health professionals in public health facilities in Garissa county

2. To establish the socio-demographic characteristics of health professionals in public health facilities that influence information seeking behaviour of health professionals in Garissa County

3 . To establish facility factors that influence information seeking behaviour of health professionals in public health facilities in Garissa County.

5 1.6 Null Hypothesis

The null hypotheses of the study were:

Ho1: There is no significant relationship between socio-demographic factors and

information seeking behaviour of health professionals;

Ho2: There is no significant relationship between facility factors and information

seeking behaviour of health professionals;

Ho2: There is no significant relationship between technological factors and

information seeking behaviour of health professionals.

1.7 Significance of the Study

The study provided key insight on the information seeking behaviour of health professionals and their information needs in health care delivery. The study also provided useful information on key factors (facility, technological and individual) influencing information seeking behaviour among the health professionals. The results and accompanied recommendations will provide useful lead to health policy and program stakeholders in developing tailored policies and initiatives for addressing identified gaps, challenges and opportunities for improving information seeking behaviour among the health professionals. The study also contributed to the available research and knowledge on health care services for documentation, further research and reference.

1.8 Scope and Delimitation

6

and non-governmental health facilities. This study was conducted among all health professionals working in public health facilities in Garrisa County and therefore its finding are generalized to all public health professionals working in public health facilities with similar characteristics.

1.9 Conceptual Framework

7

Independent variable Intervening variable Dependent variable

Source: Developed from literature Review, 2015 Figure 1.1: Conceptual framework

Facility factors Workload

Information sharing

Information guidelines

Communication channels

Resources

Data sources

Technological factors Computer proficiency

Internet Connectivity

ICT policies

ICT infrastructure

Information seeking Behaviour Socio-demographic characteristics Age Sex

Work Experience

Level of education

Profession

Work unit

Health Information

Policy

Information needs Type of Information

sought

8

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1Information Needs and Seeking Behaviour

Understanding of information needs and information-seeking behavior of various professional groups is essential as it helps in the planning, implementation and operation of information system and services in the given work settings (Avitgis et al., 2011). Reviews have indicated that public health practitioners need timely, easy to digest, and up-to-date information that is filtered and summarized from authoritative content sources (Debra & Anne, 2007). Therefore, the working environment and type of task performed by individuals shape their information needs and the ways they acquire, select and use this information.

An individual may be motivated to engage in information seeking behaviour in an attempt to fulfil his or her needs (Younger, 2010). However, it is not necessary that information needs translate into information seeking behaviour; several personal and contextual factors may enhance how an individual responds to information need (Case,et al. 2005). Information needs are thus a requirement that may drive health professionals into an information seeking process to meet their information gaps. Knowledge about the information needs, information behaviour and information seeking patterns of health professionals is crucial to effectively satisfy the felt information needs and improve the delivery of health care services in a country.

9

review of the literature on doctors’ information needs in high income countries revealed that doctors mainly needed information in the following areas: clinical care, Continuing Professional Development (CPD) and patient information (Younger 2010). Information on diagnosis and treatment were also major information needs for primary care health professionals in Spain (Gonzalez-Gonzalez et al. 2007).

Andrews and Pearce. (2005) study on information-seeking behavior of practitioners in a primary care practice based research network, whereby clinicians were asked how often they sought information from colleagues, print resources or online resources (excluding drug dosing or drug information interaction) to care for their patient, 58% stated they did this several times per week, 18% daily, 22% rarely and 2% never. Reviews reflect the fact that the information seeking behaviour of physicians is very specific, and varies from physician to physician and from location to location. This behaviour is influenced by “availability, physical distance, costs, convenience, skills and perceived relevance of information” (Kapiriri & Bondy, 2006).

10

searching were uncommon (Page & Hellers, 2000). Another source confirmed that health staff used colleagues as their first source of information (Younger, 2010).

Studies from low-income countries also showed that colleagues remained the major source of medical information for health professionals in Uganda (Tumwikirize,et al, 2009). Colleagues were used at a high rate due to their availability, affordability, and reliability. With the development of technology, the practice has started to change through the years. Some recent studies have reported Internet or electronic resources as popular sources of information for health professionals especially physicians. Other studies have reported printed materials as dominant sources of information to physicians. In summary, most research shows that health professionals rely on human sources of information (colleagues) most often (Tanneryet al, 2007), particularly for issues related to diagnosis (Cogdill, 2008). Health professionals are cited to rarely use electronic sources and new information technologies (Revere,et al, 2007).`

2.2Institutional Factors

11

quality, and format contribute to the selection and use of different information sources by scientists (Revere et al., 2007).

However, there are numerous barriers that health professionals encounter in an effort to fulfill their information needs which affect their information seeking behaviour. Miranda and Tarapanoff (2008) described these factors as personal, emotional, educational, demographic, social/interpersonal, environmental, economic, and source characteristics. The major barriers that inhibited physicians from seeking information in other high-income countries were related to time constraints, insufficient access to resources (Flynn & McGuinness, 2011), inadequate search skills, workload, cost, too much information, and liability issues (Masters, 2008). Lack of time and a distinct preference for asking an expert colleague or consulting a printed source is also major barriers to effective online searching reported by health professionals (Younger, 2010). Irregular supply, lack of time, and high access costs are also identified as the main barriers for health professionals in Uganda (Tumwikirize,et al. 2009).

2.3Technological Factors

12

healthcare delivery system in recent years, including provider-patient email exchanges, electronic records, access to laboratory results via the Internet, text messaging reminders, and the use of iPhone applications that allow you to have quick access to pertinent health information as well as to take a picture of your prescription and text it to your pharmacy for a refill (Avtgis et al, 2011).

The healthcare system in developed countries has a long and distinguished history of innovation, and when new technological advances are found to benefit healthcare delivery and the prevention of disease, it is often on the cutting edge of adopting them. For example, even the advent of the telephone was once considered a major technological advancement in terms of increasing a provider's ability to conveniently reach patients as well as seek health information. Later, beginning in the 1980s, providers began using email to communicate with other providers, followed by the use of email to communicate with patients in the 1990s (Avtgis, et al, 2011).

13

Healthcare organizations hope that the application of these technologies will reduce the costs associated with traditional channels of communication (e.g. Telephone, paper-based patient charts, and memoranda from healthcare organization administrators) and increase convenience and efficiency. New technologies can also be used in health prevention and education efforts to disseminate and access health information as well as facilitate relationships (provider—provider, provider—patient, and patient—patient) (Tu & Cohen, 2008).

14 2.4Socio-Demographic Factors

There are numerous barriers that health professionals encounter in an effort to fulfill their information needs which affect their information seeking behaviour. These factors include personal, emotional, educational, demographic, and social/interpersonal. In a study by Gavgani, it found that people who are more educated than others use internet for seeking health information (Gavgani, et al.,

2013). Another study done by Bennett et al. (2009) showed that health professionals with more education and who are younger may be more likely to use electronic sources.

2.5Research gaps

15

16

CHAPTER THREE: MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1 Study Design

A cross sectional study, takes a snapshot of a population at a certain time, allowing conclusions about phenomena across a wide population to be drawn. This helps to identify specific issues in an identified population. Therefore, this study used cross-sectional study design employing mixed methods of data collection. This design permitted collection of data about variables or subjects (health professionals) as they were found in health facilities. It was also appropriate because a considerable amount of information was obtained from sampled health professionals within a short time by use of detailed questionnaire.

3.2 Study Variables

Variables are measurable characteristics that assume different values among the subjects

3.2.1 Dependent Variable

The dependent variable shows the influence arising from the effects of the independent variables, which in this study was:

Information seeking behaviour. This was measured by the type of health

17 3.2.2 Independent Variable (s)

An independent variable is variable that a researcher manipulates in order to determine its effects on another variable (Mugenda, 2008). The independent variables of the study were:

Socio-demographic Characteristics. The study identified the influence of

Age, Sex, Experience, Level of education, Profession and work uniton information seeking behaviour of the health professionals.

Facility Factors. The study established the influence of workload, resources,

data sources, Work unit, communication channels and organizational culture on information seeking behaviour of the health professionals.

Technological Factors. The study determined the influence of ICT skills,

internet Connectivity, ICT infrastructure, computer literacy and ICT policies on information seeking behaviour of the health professionals.

Information needs. The variables studied included type of health information

sought, reasons for seeking health information and Frequency of seeking health information by health professionals.

3.2.3 Intervening Variable

The intervening variable of the study was health policies on information management.

3.3. Location of the Study

18

the North, Tana River and Isiolo counties to the west and the Republic of Somalia to the East. It has Seven (7) sub-counties namely: Garissa, Fafi, Dadaab, Lagdera, Balambala, Hulugho and Ijara. There were a total of 72 public health facilities in Garissa County with approximately 409 health professionals. Garissa County was affected by inadequate numbers of personnel. Distances to referral facilities were usually much longer, on poorer roads, than in other parts of the country. Poorly equipped facilities were also a major cause of ill-health, particularly in unplanned urban areas. The county has reported 55.8% full immunization for children under one year and 25.1% skilled birth deliveries a (Garissa County Fact Sheet, 2014).

3.4 Study Population

The study population included 409 health professionals in public health facilities (dispensaries, health centres and sub-county hospitals) in all the sub-counties in Garissa County.

3.4.1 Inclusion Criteria

The following persons were allowed to participate in the study:

All permanently employed health professionals in all the sub-counties in Garissa County

All health professional who were present at facilities at the time of data collections

Any member of the seven sub-counties who had at least six months working experience in the county as an employee

19 3.4.2 Exclusion Criteria

The study excluded the any selected respondent who was sick at the time of data collection. Four respondents were excluded using this criterion based on self report.

3.5 Sampling Technique

Garissa County was sampled purposively because it was one of the top marginalized areas categorized to have serious structural and technoligal challenges which put a strain to access of new and emerging health information.

To select the study respondents, stratified sampling was used to group the facilities into three (3) strata categorized by the type of facility i.e. dispensaries, health centres and sub-county hospitals. This ensured that the sample size was representative of the respondents across the different tiers of health service delivery. In Garissa, there are a total of 72 health facilities which comprise: 7 sub-county hospitals, 21 health centres and 44 dispensaries. This was followed by simple random sampling using table of random numbers by which 240 respondents from the three stratums were selected for the administration of the survey questionnaire. These respondents were drawn from a total of 60 health facilities in the County.

20

focus group discussions provided useful insight and views on health professionals’ information seeking behaviour at all the levels of service delivery in Garissa County.

3.6 Sample Size Determination

The quantitative sample size was determined using the formula by Fisher et al., (1998):

n=Z2P (1-P) d2

Where:

Z=Standard Normal deviation (1.96 for a 95% confidence level n = is the sample size when the population is more than 10,000

P=the proportion of the population having the characteristic being measured (if the proportion is unknown, P is set at 50% hence, P=0.5)

d=the level of accuracy desired, or the sampling error (Often set at 0.05).

Therefore, n= 1.962x0.5xo.5 = 384 Respondents 0.052

Adjustment for a population less than 10,000 (The total population of health professionals in Public Health Facilities in Garissa County was 409 (County HR office, 2014) was done using the formula:

nf= n/1+(n/N) Where:

21

N= the size of the total population for which the sample is drawn

Therefore: nf= 384.16

1+ (384.16/409) =198 Respondents

To cater for non-response, 20% (42) of the sample respondents were included in the study. The high non-response rate was due to the effect of insecurity and war in the study area which could have negative effect on availability of health professionals in the health facilitities and or non-response. Therefore, a total of 240 questionnaires were administered but 222 were returned which presents a response rate of 92.5% (Table 3.1).

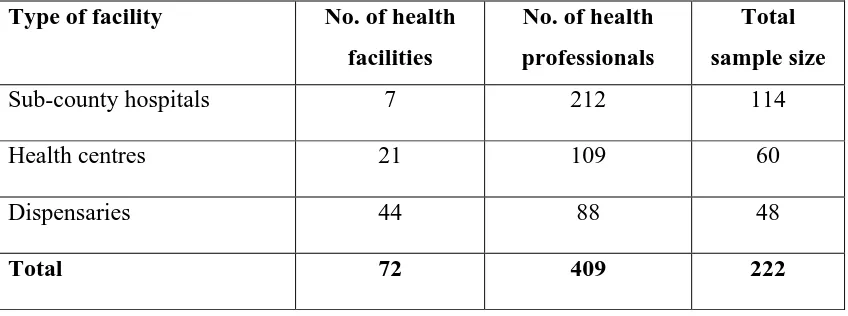

Table 3.2: Study respondents distribution Type of facility No. of health

facilities

No. of health professionals

Total sample size

Sub-county hospitals 7 212 114

Health centres 21 109 60

Dispensaries 44 88 48

Total 72 409 222

3.7 Data Collection Tools

22 3.8 Data Collection Procedures

During quantitative data collection, the lead researcher introduced himself and his research assistants to the respondent (s) who had been selected to participate in the study. The consent form was read to each respondent after which the respondent either accepted or declined to participate in the study. Any respondent who did not consent to participate was thanked for their time. Those who consented were issued with pre-tested researcher-administered questionnaires. All the respondents were allowed at least 30 minutes to fill the questionnaires after which they were collected for coding, cleaning and data entry. For key informant interviews, any respondent who consented were taken through the interview which lasted between 20-25 minutes. Key informant interviews were done following an interview schedule which detailed the time and venue of the interviews. The interview schedule was developed based on the convenience and preferences of the interviewee. A total of 15 face to face interviews were done by the principal researcher.

23

were mandatory requirements for research assistants. The lead researcher was the lead supervisor.

3.9 Pre-testing of Data Collection Tools

Pre-testing of the questionnaire was done in Isiolo County, Isiolo south sub-county, which borders Garissa County because the health facilities in sub-county were similar in most aspect to those in Garissa County and it was a distant from the selected study area. The purpose of pre-testing was to establish a common understanding of the tools by the research team and to determine the approximate time required to complete one questionnaire for purposes of ascertaining clarity and objectivity of questions. Following the pre-test, questions found to be unclear were reframed. The lead researcher closely supervised the research assistants during the data collection exercise by being available to provide guidance during the whole process of data collection in the field.

3.10 Reliability of Study Tools

During pre-testing, respondents were debriefed to test understanding and adequacy of research instruments. Subsequently, the interview tools were revised to reflect the corrections made. The responses by the respondents were then compared for internal consistency and hence, reliability.

3.11 Validity of Study Tools

24

researcher’s responsiveness were ensured in relation to the objectives of the study in order to enhance validity of the data collection instruments.

3.12 Data Analysis

Analysis of data involved quantitative and qualitative approaches. Quantitative data was first compiled and coded into SPSS Version 20. Questionnaires with missing data were discarded. A data entry screen was prepared in SPSS Version 20 for quantitative data and Nvivo for qualitative data. Descriptive statistics was used to describe study variable outcomes using frequencies and percentages. Multi-normial regression analysis was used to explore and understand the data collected because the dependent variable (health information resources) were multinomial in nature. Statistical significance for testing hypothesis using regression model was inferred at 5 percent.

In qualitatitative data, thematic analysis using Nvivo was undertaken to identify emerging themes and triangulate the quantitative findings. Data which was recorded during data collection, was coded and entered into the Nvivo software afterwhich it was categorized into themes. Patterns in the data were studied and themes developed. The results were used to give insight and triangulate quantitative results of the study. Verbatims statements were used to present key statements from the themes developed.

3.13 Ethical Considerations

25

26

CHAPTER FOUR: RESULTS

This chapter presents the findings of the study based on research objectives. The results are presented as follows: socio-demographic characteristics, facility factors, technological factors, health information needs and information resources.

4.1Background Characteristics of Respondents

This section presents the background characteristics of the study respondents which include age, sex, level of education, profession and work experience (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1: Age, gender ,education level, profession and work experience of respondents

Characteristics N=222 %

Age 21-30 yrs 115 51.8

31-40 yrs 70 31.5

41-50 yrs 37 16.7

Gender Male 129 58.1

Female 93 41.9

Education Level Certificate 21 9.5

Diploma 147 66.2

Higher Diploma 18 8.1

Degree 32 14.4

Masters 4 1.8

Profession Nurses 90 40.5

Clinical Officers 53 23.9

Nutritionists 17 7.7

Public Health Officers 31 14.0

Lab tech 14 6.3

Pharmaceutical Technologists 7 3.2

HROs 10 4.5

Work experience 2 years and below 58 26.1

3-5 years 81 36.5

6-9 years 29 13.1

27

Out of the 222 study respondents, about half of the respondents (115; 51.8%) were aged 21-30 years while 16.7% (37) of the respondents were aged 41-50 years. In relation to gender, majority of the respondents (129; 58.1%) were males while females comprised 41.9% of the study respondents. In terms of educational level, the highest number of respondents (147; 66.2%) were diploma holders followed by degree holders (32; 14.4%) while respondents with master degree (4; 1.8%) formed the smallest proportion of the study respondents.

In relation to work experience, majority of the respondents (139; 62.6%) had work experience of 5 years and below while only 24.3% had work experience spanning over 10 years. In relation to respondents’ profession, more than a third of the respondents (90; 40.5%) were nurses. Pharmaceutical technologist and health records and information officers formed the smallest proportion of 3.2% and 4.5% respectively.

4.2Health Information Needs

This section presents descriptive and qualitative results on information needs of health professionals. The results include information on type of information sought, reasons for seeking information and patterns of information seeking.

4.2.1 Type of health information sought

28 Figure 4.1 Type of health information sought

Qualitative results revealed that the main health information sought was on new health issues and updates, medical diagnosis and treatments such as Ebola disease. However, the kind of information sought depends on the profession and existing information gaps. A statement from key informants’ interview explains:

“…All health professionals depending on profession are provided with

basic information for service delivery. However, health workers need

to constantly and regularly keep themselves updated on new health

updates and emergencies within their profession and other issues of

29 4.2.2 Reasons for seeking health information

Figure 4.2 summarizes results for reasons for seeking health information. Analysis revealed that the main reason cited for seeking health information related to work was need to upgrade skills and knowledge (33.3%), questions from clients (19.9%) and emergence of new methods and technologies (19..6%).

Figure 4.2 Reasons for seeking health information

30

“….I seek information regularly to help me respond to queries from my

colleagues and clients…it’s is also important to remain updated on

new and emerging issues within your profession, otherwise, you will be

redundancy…”

4.2.3 How Health professionals seek health information

Figure 4.3 summarizes results on how health professionals seek health information. Majority of the respondents (190; 85.6%) sought health information related to their work when need arises while only 42(14.4%) respondents sought health information on daily basis.

On need basis 86% On daily basis

14%

Figure 4.3 How health professionals seek health information

Qualitative results showed that HPs seek information mainly during emergencies and when new updates are available such as new therapies and medical technologies, new regulations among others. The following remark from one of the key informants supports this finding:

“…Yeah, information is required on daily basis but since most of it is

31

done. Most HPs seek information to fulfil identified needs and this

happens only when a specified and pressing need arises…”

4.3Information Seeking Behaviour

This section covers results on information seeking behaviour (information resources used) of HPs.

4.3.1 Type of information resources used

Figure 4.4 summarizes findings for type of information resources used by HPs. In this study, information seeking behaviour was defined by the different types of health information resources employed by health professional to access health information they need.

32

Results showed that majority of the respondents (114; 51.4%) used informal resources (colleagues and senior staff/supervisors) to get health information related to their work. IT-based resources were the least used to get health informational resources.

Qualitative results revealed that HPs relied mainly on information provided by colleagues in their profession. IT-based resources were not commonly used due to poor internet connectivity and ICT infrastructural support. A statement from a FGD discussant explains:

“…I rarely use internet to get key information regarding my work

because even if I want, there is no connectivity. I find it easy to consult

my colleagues within my profession especially my workmates because

they are easy to access, reliable and saves time…However, when need

arises; I consult manuals and SOPs…”

4.3.2 Frequency of health information resources use

33

Table 4.2: Frequency of using information resources

Results indicated that majority of the respondents mainly (often and always) used colleagues (82.7%) followed by supervisors/senior staff (56.3%) and standard guides (45%) to obtain the health information related to their work. Electronic books, followed by audio-visual materials and electronic journals constitute resources least used by the respondents.

4.4Socio-Demographic Factors

This section presents results regarding influence of socio-demographic characteristics on information seeking behaviour of health professionals.

4.4.1 Influence of age and sex on information seeking behaviour

34

Table 4.3: Influence of age and gender on information seeking behaviour

Type of

resource Variable B

Std.

Error Wald df Sig. Exp(B)

95% CI for Exp(B) Lower Upper

Age 13.104 4 0.011

Print resources

21-30 yrs 1.013 0.499 4.130 1 0.042 2.754 1.037 7.317 31-40 yrs 1.154 0.535 4.656 1 0.031 3.172 1.112 9.054

41-50 yrs 0b 0

IT-based resources

21-30 yrs -.394 0.533 0.546 1 0.460 0.674 0.237 1.918 31-40 yrs .755 0.524 2.077 1 0.150 2.128 0.762 5.943

41-50 yrs 0b 0

Gender 0.230 2 0.891

Print resources

Male -.136 0.306 0.197 1 0.657 0.873 0.479 1.590

Female 0b 0

IT-based resources

Male -.119 0.383 0.097 1 0.756 0.888 0.419 1.880

Female 0b 0

a. The reference category is: Informal resources.

b. This parameter is set to zero because it is redundant.

Age of the respondent was significantly associated with the type of resource used to obtain health information (X2=13.104; P=0.011). The age of the health professionals was significantly associated with use of print resources. A health professional aged 21-30 years was 2.754 times more likely to use print resources compared to one aged 41-50 years (P=0.042; OR=2.754). Further, a health professional aged 31-40 years was 3.172 times more likely to use print resources compared to one aged 41-50 years. (P=0.31; OR=3.172). However, age was not associated with use of IT-based resources (P>0.05).

35

have difficulties in using IT-based resources due to lack of basic IT skills. A key informant stated:

"...Technology is advancing, most of the information is in the internet

and the professionals who trained some years ago may not be

conversant with IT-based resources; to them accessing such resources

might be a challenge…"

Gender of the health professional was not significantly associated with the type of resource used to obtain health information (X2=0.23; P=0.891). This was confirmed by qualitative findings as explained by one of the statements extracted from key informants’ interview:

“… Sex does not affect information resources used by health

professionals. Whether you are a male or female, it has nothing to do

with how one seeks information relating to his/her work…”

4.4.2 Influence of Education and Profession on information seeking behaviour

36

Table 4.4: Influence of education and profession on information seeking behaviour

Type of

resource Variable B

Std.

Error Wald df Sig. Exp(B)

95% CI for Exp(B) Lower Upper

Education level 7.279 8 0.507

Print resources

Certificate -.357 1.498 0.057 1 0.812 0.700 0.037 13.179 Diploma -.353 1.426 0.061 1 0.805 0.703 0.043 11.491

Higher

diploma

-.811 1.537 0.279 1 0.598 0.444 0.022 9.032 Degree -1.05 1.481 0.503 1 0.478 0.350 0.019 6.376

Masters 0b 0

IT-based resources

Certificate -1.61 1.360 1.400 1 0.237 0.200 0.014 2.876 Diploma -1.95 1.249 2.442 1 0.118 0.142 0.012 1.642 Higher

diploma

-1.281

1.346 0.906 1 0.341 0.278 0.020 3.884

Degree -2.08 1.323 2.471 1 0.116 0.125 0.009 1.671

Masters 0b 0

Profession 9.033 12 0.700

Print resources

Nurses .028 0.483 0.003 1 0.954 1.028 0.399 2.652 CO -.148 0.528 0.079 1 0.779 0.862 0.306 2.427 Nutritionists .377 0.668 0.319 1 0.572 1.458 0.394 5.396 PHO .693 0.738 0.882 1 0.348 2.000 0.471 8.494 Lab techs 1.204 0.963 1.562 1 0.211 3.333 0.505 22.017 Pharmacists -1.57 1.141 1.889 1 0.169 0.208 0.022 1.951

HRIO 0b 0

IT-based resources

Nurses -.449 0.550 0.667 1 0.414 0.638 0.217 1.875 CO -.408 0.596 0.469 1 0.494 0.665 0.207 2.138 Nutritionists -.624 0.914 0.467 1 0.494 0.536 0.089 3.210 PHO .251 0.862 0.085 1 0.771 1.286 0.237 6.963 Lab techs .069 1.307 0.003 1 0.958 1.071 0.083 13.896 Pharmacists -1.32 1.155 1.300 1 0.254 0.268 0.028 2.578

HRIO 0b 0

a. The reference category is: Informal resources.

b. This parameter is set to zero because it is redundant.

37

qualitative data showed that preferences for information resources are not influenced by education level as supported by a FGD discussant quote below:

"…From experience, type of health information resources don’t

depend on your educational qualification. It's purely based on previous

experiences, personal preferences and quality of the resources….."

Profession of the health professional was not significantly associated with the type of resource used to obtain health information (X2=9.033; P=0.700). However, findings from KII and FGD indicated that although profession does not influence the information resources utilized by health staffs, it influences the type of information they look for. A statement from key informants’ interview underscores the finding:

“…Profession has an effect on the type of information one look for but

not on the type of resource used to get information. For example if you

have a clinical officer or a nurse in the consultation room, he would

want a lot of information on new treatment as opposed to a public

health officer who will seek information on disease prevention.

However, the type of resources used to obtain the information depends

on factors other than the profession such as quality and reliability of

the resource. This can be print, electronic or even colleagues…”

4.4.3 Influence of Work Experience on Information Seeking Behaviour

38

Table 4.5: Influence of work experience on information seeking behaviour

Type of

resource Variable B

Std.

Error Wald df Sig. Exp(B)

95% CI for Exp(B) Lower Upper

Experience 16.051 6 0.013

Print resources

≤ 2 yrs .679 0.458 2.196 1 0.138 1.973 0.803 4.845 3-5 yrs .902 0.436 4.277 1 0.039 2.464 1.048 5.792 6-9 yrs .931 0.578 2.591 1 0.107 2.536 0.817 7.877

> 10 yrs 0b 0

IT-based resources

≤ 2 yrs -1.24 0.624 3.955 1 0.047 0.289 0.085 0.982 3-5 yrs -.397 0.475 0.697 1 0.404 0.673 0.265 1.707 6-9 yrs .668 0.558 1.435 1 0.231 1.951 0.654 5.823

> 10 yrs 0b 0

a. The reference category is: Informal resources.

b. This parameter is set to zero because it is redundant.

Experience of the health professional was significantly associated with the type of resource used to obtain health information (X2=16.051; P=0.013). The experience of the health professionals was significantly associated with use of print resources. A health professional with an experience of 3-5 years was 2.464 times more likely to use print resources compared to a health professional with an experience of over 10 years (P=0.039; OR=2.464). However, experience was not associated with use of IT-based resources (p>0.05).

39

“…Experience matters a lot; those who have served like for three

years will remain stacked with textbooks and guides unlike a staff who

have served for like 20 years who has a big network. A staff with a

longer experience can talk to colleagues in other facilities...”

In addition, it was reported that experience influenced the amount of information a health professionals needs and hence the frequency of seeking health information relating to their profession. The following statement was extracted from a FGD discussion to support the findings:

“…In my view, experience influence information seeking behaviour

because it determine how much information relating to the work a

health profession will look for. If one has served for many years,

he/she can easily become an expert in the profession as opposed to a

newly employed staff who will constantly need to look for resources to

get information relating to his daily duties…”

40 4.5Facility factors

This section presents descriptive, multinomial regression analysis and qualitative results regarding facility factors studied which includes workload, information sharing, information exchange guidelines, form of data storage, allocation of funds for addressing information needs for HPs and channels used in communicating new information.

4.5.1 Workload, information sharing and guidelines for information exchange

Table 4.6 summarizes results for workload, information sharing and existence of guidelines for access and exchange of information.

Table 4.6: Workload, information sharing and information guidelines

Variable

Frequency (n=222)

Percent (%) Nature of Workload The work I am assigned to

do is of my expectation

151 68.0

I do more work at my workplace than I expect to do

71 32.0

Sufficiency of health information sharing

Yes 84 37.8

No 138 62.2

Existence of information sharing guidelines

No 222 100.0

41 4.5.2 Data storage and allocation of funds

Results for data storage and allocation of funds are summarized in table 4.7.

Table 4.7: Form of data storage and fund allocation

Variable

Frequency (n=222)

Percent (%)

Form of data storage Electronic system 12 5.4

Manual System 83 37.4

Both electronic and manual system

127 57.2

Allocation of funds to address information needs

Yes 24 10.8

No 198 89.2

Use of both electronic and manual data storage system (127; 52.3%) was the main method of health data/information storage. Similarly, almost equal proportions of respondents (116; 52.3%) use both electronic and file data for information in discharging their duties. All the respondents (222; 100%) reported that no funds are allocated to help address health information needs of health professionals at their respective facilities.

4.5.3 Communication channels used to communicate new health information

42

Figure 4.5: Communication channels used to convey new health information

Results showed that meetings was the main channel used to communicate health information to health professionals (35.2%), followed by use of notices (21.7%) and memos (0.7%).

4.5.4 Influence of facility factors on information seeking behaviour

43

4.5.4.1Influence of workload and information sharing on information seeking behaviour

Table 4.8 presents results on influence of workload and information sharing on information seeking behavior of health professionals.

Table 4.8 Influence of workload and information sharing on ISB of HPs

Type of

resource Variable B

Std.

Error Wald df Sig. Exp(B)

95% CI for Exp(B) Lower Upper

Workload 76.834 2 0.000

Print resources

Moderate 3.088 0.459 45.280 1 0.000 21.931 8.922 53.910

High 0b 0

IT-based resources

Moderate 2.989 0.512 34.057 1 0.000 19.875 7.282 54.243

High 0b 0

Information sharing 25.912 2 0.000

Print resources

Yes 1.400 0.327 18.393 1 0.000 4.057 2.139 7.694

No 0b 0

IT-based resources

Yes 1.458 0.417 12.206 1 0.000 4.295 1.896 9.730

No 0b 0

a. The reference category is: Informal resources. b. This parameter is set to zero because it is redundant.

44

Responses from KII and FGD revealed that the workload of health professionals influences the type of information resources they use to get information. HPs with higher workload have a tendency to use informal resources compared to IT-based and Print resources due to lack of time and ease of access. The following statement from a key a FGD captures the point:

“… When a staff is overwhelmed by work, especially in rural facilities

where there is only one staff doing all the work of clerking, consulting

to dispensing, I don’t think they will have time to look at books and

other print materials. In most instances, they consult from colleagues

within the facility and from other facilities when necessary …”

Information sharing was also significantly associated with the type of resource used to obtain health information (X2=25.912; P=0.000). Sharing of information among health professionals was significantly associated with use of both print and IT-based resources. A health professional working in a facility which sufficiently shares health information was 4.057 times more likely to use print resources compared to one working in a facility with insufficient information sharing (P=0.000; OR=4.057). On the other hand, a health professional working in a facility with adequate sharing of heath information was 4.295 more like likely to use IT-based resources compared to one working in a facility with insufficient sharing of health information.

45

which are easily accessible. The following quote from key informants’ interview explains:

“… In our facilities, especially those in rural areas, information

sharing is actually a very big challenge because most of the

information is shared once in three months when we have our

quarterly meeting. At times, HPs are forced to look for extra

information relating to their work from else where like from

internet…”

4.5.4.2Influence of form of data storage on information seeking behaviour

Table 4.9 presents results on influence of form of data storage on information seeking behavior of health professionals among health professionals.

Table 4.9 Influence of form of data storage on information seeking behavior

Type of

resource Variable B

Std.

Error Wald df Sig. Exp(B)

95% CI for Exp(B) Lower Upper

Form of Data Storage 3.942 4 0.414

Print resources

Electronic .110 0.700 0.025 1 0.875 1.116 0.283 4.401 Manual -.381 0.319 1.420 1 0.233 0.683 0.365 1.278

Both 0b 0

IT-based resources

Electronic .405 0.769 0.278 1 0.598 1.500 0.332 6.774 Manual -.673 0.423 2.534 1 0.111 0.510 0.223 1.168 Both electronic

and manual

0b 0

a. The reference category is: Informal resources. b. This parameter is set to zero because it is redundant.

46

indicated that the form does not influence they type of information resources used by staffs used to get health information relating to their roles and responsibilities. A quote from FGD put it:

“…Well, if the data storage system is electronic, it does not mean that

health professionals will adopt electronic resources more than print

and use of colleagues…For instance, in most cases, data is stored

manually in our facilities but whenever HPs need new information or

updates they either consult colleagues or search for it online

depending on nature of the information such as published guidelines in

the ministry website…”

In summary, regression results indicated a statistically significant relationship between workload, information sharing culture and information seeking behaviour of HPs (P<0.05). Therefore, the null hypothesis that facility factors are not associated with information seeking behaviour was rejected.

4.6Technological factors

47 4.6.1 Computer proficiency and ICT skills

Results on computer proficiency and ICT skills among health professionals are presented in Table 4.10.

Table 4.10: Computer proficiency and ICT skills

Variable

Frequency (n=222)

Percent (%) I know how to operate basic microsoft office application Yes 160 72.1

No 62 27.9

I know how to search for informatio on internet Yes 120 54.1

No 102 55.9

I know how to save/store information/data downloaded from internet

Yes 193 86.9

No 29 13.1

I know how to analyse digital data for use Yes 134 60.4

No 88 39.6

I know how to interpret digital data for use Yes 165 74.3

No 57 25.7

I know how to send digital data to other receipient Yes 172 77.5

No 50 22.5

Results showed that majority of the respondents (160; 72.1%) were able to operate Microsoft office while more than half (120; 54.1%) were able to search for information related to their work in the internet. 86% of the respondents were able to save/store information downloaded from the internet. 60% (134) of the respondents had ab ility to analyze digital data while 165 (74.3%) had ability to interpret digital data. 172 (77.5%) of the respondents were able to send digital data to others.

4.6.2 ICT policy, internet access and functionality of ICT tools

48

Table 4.11: ICT policy, internet connectivity and adequacy of functional ICT tools

Variable

Frequency (n=222)

Percent (%) Existence of policy to guide ICT adoption and use No 222 100 I have access to internet in the health facility Yes 16 7.2

No 206 92.8

There are functional ICT tools in the facility Yes 37 16.7

No 185 83.3

My department has adequate ICT tools for use Yes 31 14

No 191 86

All the respondents (222; 100%) said that there was no ICT policy to guide its adoption and use in their work places. Further, only 80 (36%) of the respondents had access to internet in their facilities. Only 23.4% of the respondents said that their facility had functional ICT tools while only 31 (14%) reported adequacy of ICT tools for use in their work units/departments.

4.6.3 Influence of technological factors on information seeking behaviour

4.6.3.1Computer proficiency and internet search ability

49

Table 4.12: Influence of Computer literacy and ICT skills on information seeking behaviour

Type of

resource Variable B

Std.

Error Wald df Sig. Exp(B)

95% CI for Exp(B) Lower Upper Microsoft office

proficiency 2.21 2 0.000

Print resources

Yes 1.29 .325 15.74 1 0.000 3.635 1.921 6.877

No 0b 0

IT-based resources

Yes 1.35 .416 10.49 1 0.001 3.849 1.702 8.702

No 0b 0

Internet search ability 34.98 2 0.000

Print resources

Yes 1.70 .336 25.44 1 0.000 5.447 2.819 10.525

No 0b 0

IT-based resources

Yes 1.61 .419 14.74 1 0.000 4.995 2.197 11.355

No 0b 0

Computer proficiency was significantly associated with the type of resource used to obtain health information (X2=2.21; P=0.000). Computer proficiency was significantly associated with use of both print and IT-based resources. A health professional who was computer proficient was 3.635 times more likely to use print resources compared to one who was not (P=0.000; OR=3.635).

50

A FGD underscored the relationship between computer literacy and the type of information sources used by health professionals in the following statemente:

“… Honestly speaking, if a staff is lacking in computer skills, it will be

hard to find him or her going for electronic sources but instead he/she

will consult colleagues or use textbooks and such resources…”

Ability to search internet was significantly associated with the type of resource used by health professional to obtain health information (X2=34.978; df=2, P=0.000). Internet search ability was significantly associated with use of both print and IT-based resources. A health professional who was able to search internet was 5.447 times more likely to use print resources compared to one who was not (P=0.000; OR=5.447).

On the other hand, a health professional with ability to search internet was 4.995 more likely to use IT-based resources compared to one who was not (P=0.000; OR=4.995). Qualitative findings reported that internet search ability enables HPs to access health updates and information relating to their work more easily and from wider resources supported by IT-applications. However, internet connectivity remained a major challenge in accessing and using these resources. A remark from an FGD puts:

“….Although Microsoft proficiency is key in using IT-based resources;

I find it important to be able to search for required information from

both relevand and authoritative sources in the internet. But the

greatest hinderence to using the electronic resources is poor network

51

4.6.3.2Ability to save downloads and analyze digital data

Table 4.13 presents results on influence of ability to save downloads and save digital data on information seeking behaviour among health professionals.

Table 4.13: Influence of ability to save downloads and analyze digital data on information seeking behaviour

Type of

resource Variable B

Std.

Error Wald df Sig. Exp(B)

95% CI for Exp(B) Lower Upper

Ability to save data 2.82 2 0.237

Print resources

Yes 0.77 .495 2.44 1 0.118 2.167 .821 5.719

No 0b 0

IT-based resources

Yes 0.50 .586 0.73 1 0.393 1.650 .523 5.204

No 0b 0

Ability to analyze

digital data 63.34 2 0.000

Print resources

Yes 2.64 .423 38.96 1 0.000 14.021 6.119 32.128

No 0b

0

IT-based resources

Yes 2.03 .463 19.27 1 0.000 7.631 3.080 18.905

No 0b 0

Ability to save information dowloaded from internet was not significantly associated with the type of resource used by health information to obtain health information (X2=34.978; P=0.237). KII and FGD findings indicated that ability to save internet based information doesn’t inform individual choices on the resources they use. A key informant remark supports this point:

“…From experience, being able to use computers and search for

information from internet resources is can encourage HPs to use

internet based resources but not ability to save /store the downloaded

52

Ability to analyse digital data was significantly associated with the type of resource used by health information to obtain health information (X2=63.335;df=2; P=0.000). Digital data analysis ability was significantly associated with use of both print and IT-based resources. A health professional who was able analyse digital data was 14.021 times more likely to use print resources compared to one who was not (P=0.000; OR=14.021).

On the other hand, a health professional with ability to analyse digital data was 7.631 more likely to use IT-based resources compared to one who was not (P=0.000; OR=7.631). Qualitative results reported insufficiency of digital data analysis skills among HPs. Ability to analyze digital data increases preferences for digital resources such as electronic resources and print resources in which data/information relating to their work can be accessed. Such professionals are reported to easily make sense of both simple and complex data from various resources relating to their work. A key informant quote illustrates this finding:

“…Yeah, professionals who have skills to analyze data in their

professions have an advantage of understanding and comprehending

raw and analyzed informations from many sources in their field of

practice. Such professionals are motivated to looks for more

authoritative sources which mainly come from print and electronic

sources such as internet and institutional websites….”

4.6.3.3Data interpretation and sending ability