FREE SCHOOLS IN ENGLAND: CHOICE,

ADMISSIONS AND SOCIAL

SEGREGATION

By

REBECCA MORRIS

A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

School of Education

University of Birmingham

February 2016

University of Birmingham Research Archive

e-theses repositoryThis unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation.

Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder.

ABSTRACT

This study examines the operation of school choice in the context of Free Schools in England. It focuses on three different aspects, each related to exploring the Free Schools policy from a social justice and equity perspective. The first of these looks at the admissions arrangements of

secondary Free Schools, and considers the extent to which they have the potential to impact local patterns of social segregation between schools. Second, the reasons and strategies that parents reported when choosing a Free School are explored. Finally, the study explores the outcomes in relation to student composition. The study as a whole takes a multi-method approach, using Annual School Census data, parent questionnaires and interviews and a documentary analysis of admissions policies.

The findings show a complex picture, reflecting the heterogeneous and diverse nature of Free Schools. Disadvantaged pupils are under-represented in a majority of Free Schools, but not in all. The admissions policies also suggest that the majority of Free Schools are using similar methods for allocating places as those used by other schools in their area. A small number, however, are seeking to use more equitable methods such as banding or random assignment. Parents that had chosen the Free Schools tended to report looking for similar features but had taken different routes and encountered varying circumstances during the decision-making process. Many were attracted to the Free School by its promise of quality and used a range of proxy features to determine this, including factors relating to the social composition of the Free School, comparisons with other school types and a focus on a traditional approach to schooling.

Recommendations for how the Free Schools policy could be used to encourage equity of access and opportunity are included at the end of the study. These include potential changes to school admissions procedures and continuing to encourage wider access to information about schools. In a number of instances though it is suggested that rather than simply focusing on particular types of school, policymakers should seek to implement these suggestions on a national scale if they are interested in making the ‘choice’ process fairer for all.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research would not have been possible without the three-year studentship that I received from the School of Education at the University of Birmingham. I will always be very grateful for this support.

I would also like to warmly thank both of my supervisors: Professor Peter Davies at the University of Birmingham and Professor Stephen Gorard at Durham University. It has been a real privilege to work with such enthusiastic, experienced and committed researchers and I am grateful for the support, motivation and valuable critique that has helped me to complete this project.

A number of schools kindly agreed to participate in this study; I appreciate their willingness to be involved and thank the staff who supported my data collection and the many parents that kindly volunteered to participate.

I would like to thank Dr Kay Fuller (now at the University of Nottingham) for first encouraging me to consider applying for a PhD. I am also grateful to friends and colleagues within the School of Education and within the local schools where I have worked who have provided support and encouragement at numerous points throughout this study.

I have been lucky enough to share my time at the University of Birmingham with a number of other postgraduate researchers. Many have become good friends and I am grateful for their interest in my work and their comments and suggestions on how to improve it. Special thanks here go to Tom Perry who has been an excellent PhD companion, always willing to discuss and debate ideas, and always a source of humour and reassurance when it was most needed.

Finally, I would like to thank my family and friends for their support. And to Matt, for always making things seem possible.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Page

Introduction

1

1.1 Statement of purpose

1.2 Significance of the study

1.3 Research questions

1.4 Overview of design and methods

1.5 Theoretical framework

1.6 Scope of the study and limitations

1.7 Structure of the thesis

Chapter 2

Policy Context

11

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Conservative government schooling reforms (1979-1997)

2.3 The New Labour Years (1997-2010)

2.3.1 Changes and continuation of Conservative policy 2.3.2 Admissions and allocation procedures

2.3.3 The Learning and Skills Act 2000: introduction of the first academies

2.4 The Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition and the expansion of the

academies programme (2010-present) 2.4.1 Introduction of converter academies 2.4.2 Free Schools

Chapter 3

Free Schools: a theoretical framework

23

3.1 Introduction

3.2 Monopoly public schooling

3.3 The market model and ‘quasi-markets’

3.4 Choice and diversity for its own sake

3.5 Competition, standards and freedom of entry and exit

3.6 School autonomy, choice and responsiveness

3.7 Quasi-market reforms, choice and equity

3.7.1 Improving equity through choice and diversity 3.7.2 Choice, inequity and stratification

3.8 Conclusion

Chapter 4

Social composition, parental choice and admissions:

41

the research literature

4.1 Introduction

4.2 The social composition of schools

4.2.2 School composition and international policy contexts 4.2.3 Segregation

4.3 School choice and the role of the parent 4.3.1 Who chooses schools?

4.3.2 When does the choice process begin?

4.3.3 Identifying performance: formal information 4.3.4 Informal information about schools

4.3.5 Different ‘types’ of chooser

4.3.6 What are parents looking for in schools?

4.3.7 Does social background influence school choice? 4.3.8 Gaining places

4.4 Choice and the role of the admissions process

4.4.1 Changes to admissions policy and legislation: 1998-2014 4.4.2 How do schools allocate their places?

4.4.3 Admissions, allocation procedures and equity 4.4.4 Autonomous schools and admissions

4.4.5 The impact of recent changes to policy and legislation 4.5 Conclusion

Chapter 5

Research Design and Methods

80

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Research questions and strategy

5.3 Research design

5.3.1 Intervention and sequence of data collection 5.3.2 Identification of cases and allocation to groups

5.4 Methods

5.4.1 Combined methods research in this project 5.4.2 Secondary data 5.4.3 Documentary data 5.4.4 Parent survey 5.4.5 The interviews 5.5 Ethical considerations

Chapter 6

Prioritising places: the admissions criteria of secondary

108

Free Schools

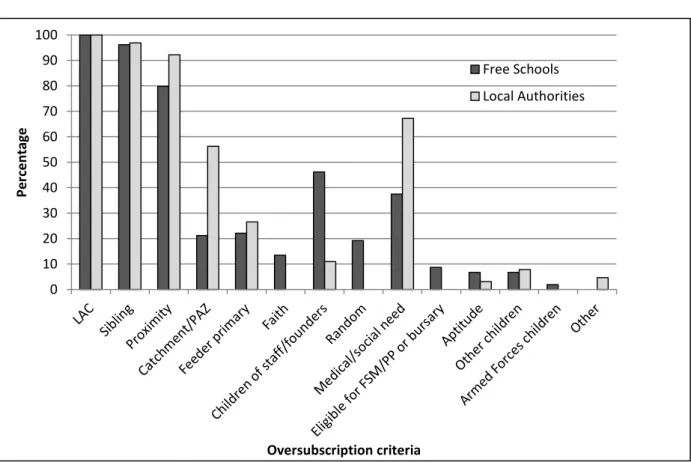

6.1 Use of oversubscription criteria in admissions policies

6.1.1 Number of criteria used 6.1.2 Frequency of criteria use

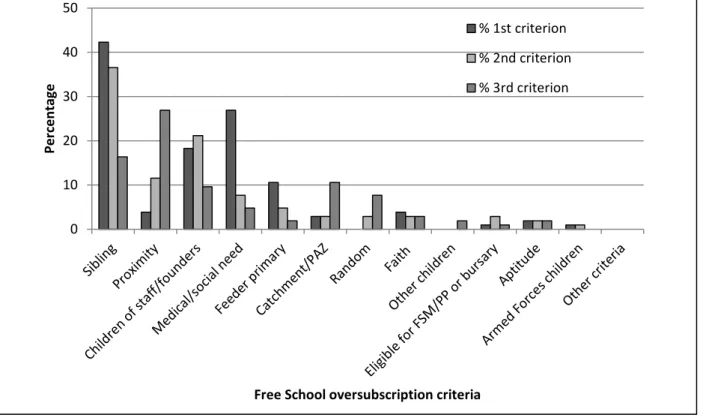

6.1.3 Ranking of oversubscription criteria

6.2 Allocation methods and oversubscription criteria

6.2.1 Priority for SEN and Looked After children 6.2.2 Criteria relating to ability or aptitude

6.2.4 Criteria relating to children of founders or current staff 6.2.5 Faith criteria 6.2.6 Geographical criteria 6.2.7 Feeder schools 6.2.8 Pupil Premium 6.2.9 Random assignment 6.3 Discussion 6.4 Conclusion

Chapter 7

Choosing a Free School: reasons, strategies and the role

135

of parents

7.1 What were Free School parents looking for?

7.1.1 Academic quality and performance 7.1.2 Academic quality and social distinction 7.1.3 Personalisation and holistic education

7.1.4 Convenience

7.2 Information and choice strategies

7.2.1 Information used during the choice process 7.2.2 Experience of the choice process

7.2.3 Three ‘types’ of chooser

7.3 Discussion

7.3.1 Parent choice and the aims of the Free Schools policy 7.3.2 Free School choice: more of the same?

7.4 Conclusion

Chapter 8

Free Schools and disadvantaged intakes

181

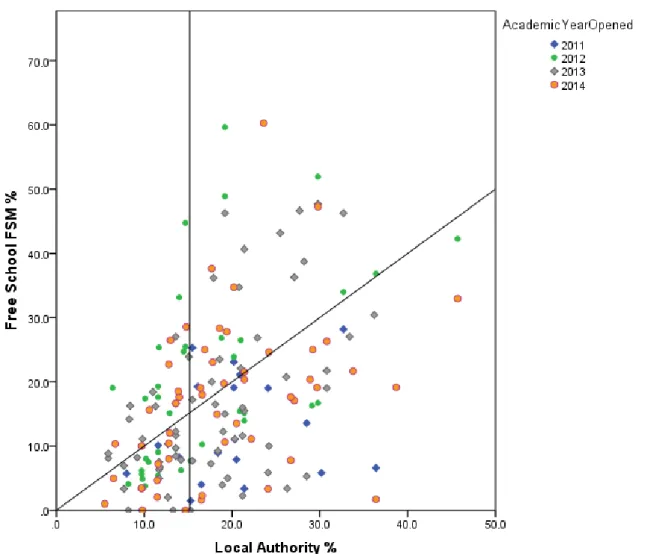

8.1 Free Schools and disadvantaged intakes in 2015

8.2 Free School intakes over time

8.2.1 Wave 1 Free Schools 8.2.2 Wave 2 Free Schools 8.2.3 Wave 3 Free Schools

8.3 Case study schools

8.3.1 Schools that are under-representing FSM children 8.3.2 Schools that are moderately representing FSM children 8.3.3 Schools that are over-representing FSM children

8.4 Discussion

8.5 Conclusion

Chapter 9

Conclusions and implications of the findings

214

9.1.1 Research Question 1: What allocation methods are Free Schools choosing to use in order to prioritise their available places?

9.1.2 Research Question 2: Why (and how) do parents choose a newly- opened Free Schools for their child?

9.1.3 Research Question 3: Are Free Schools taking an ‘equal share’ of socially disadvantaged pupils?

9.2 Limitations of the study

9.3 Implications for policy

9.4 Implications for research

9.4.1 A holistic approach to policy evaluation 9.4.2 A new context for school choice research 9.4.3 Gaining wider access to the views of parents 9.4.4 Parents as ‘providers’ and ‘consumers’

9.5 Final thoughts

References

Appendices

LIST OF TABLES

Table Number

Table 1.1 Research questions and data collection methods

Table 2.1 Number of sponsored and converter academies open in England

Table 2.2 Number of Free Schools opened each year

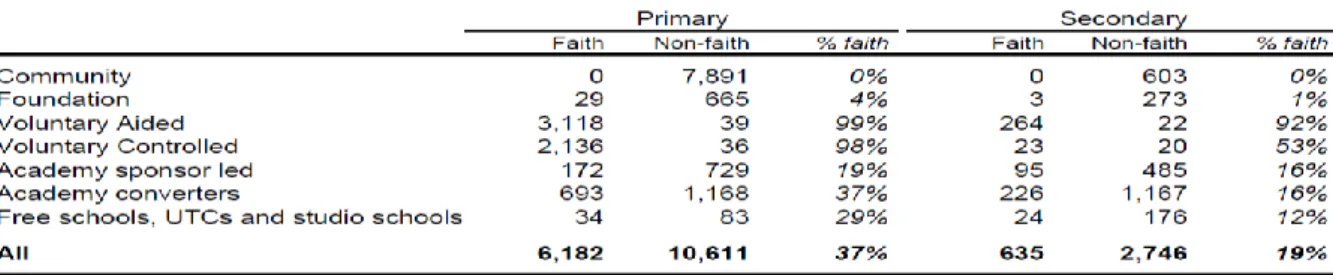

Table 4.1 Mainstream state-funded schools in England by status and religious character,

September 2015

Table 4.2 The number and proportion of schools and pupils by religious character (in

England)

Table 6.1 Number of oversubscription criteria used by Free Schools and LAs

Table 6.2 Oversubscription criteria used by secondary Free Schools

Table 7.1 Percentage of parents reporting each factor as ‘very important’

Table 7.2 Percentage of parents who reported convenience factors as ‘important’ or ‘very

important’

Table 7.3 Percentage of parents reporting sources of information as ‘important’ or ‘very

important’

Table 7.4 Parents’ views of the application process

Table 8.1 Range of Free School FSM percentages for each wave

Table 8.2 Representation of FSM children in mainstream Free Schools by school phase

(age)

Table 8.3 Percentage of FSM-eligible pupils at each Wave 1 Free School in 2011

compared with local and LA averages

Table 8.4 Frequency and percentage of FSM-eligible children in Wave 2 Free Schools.

2012-2014.

Table 8.5 Frequencies of Free Schools in different SR ranges: 2012-2014

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure Number

Figure 5.1 Overview of research questions and data collection methods

Figure 6.1 Percentage of Free Schools and Local Authorities using different criteria

Figure 6.2 Percentage of Free Schools and their ranking of each oversubscription criteria

Figure 6.3 Percentage of LAs and their ranking of each oversubscription criteria

Figure 8.1 Free School FSM proportions compared with corresponding LA (2014-2015)

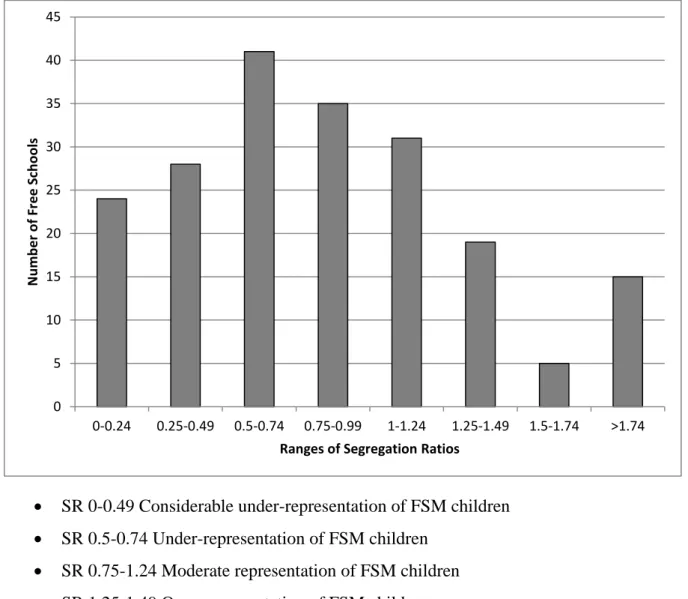

Figure 8.2 Frequency of segregation ratios (SRs) of all mainstream Free Schools

(2014-2015)

Figure 8.3 Percentage of primary, secondary and all-through Free Schools over or

under-representing FSM children.

Figure 8.4 Percentage of Free Schools from each wave and their representation of FSM

eligible children in 2014-2015

Figure 8.5 Percentage of FSM children in each wave since opening

Figure 8.6 Differences between FSM proportions of Wave 1 Free Schools and LAs (2012

and 2013 intakes)

Figure 8.7 Segregation Ratios of Wave 1 Free Schools (2012 and 2013 intakes)

Figure 8.8 Percentage point difference between Free School and LA FSM proportions:

2012 and 2014 intakes

Figure 8.9 Number of Wave 2 Free Schools under or over representing FSM children.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ASC Annual Schools Census

BBC British Broadcasting Corporation

BERA British Educational Research Association

BSA British Social Attitudes (Survey)

CTC City Technology College

DES Department of Education and Science

DfE Department for Education

DfEE Department for Education and Employment

DfES Department for Education and Skills

EAL English as an Additional Language

ERA Education Reform Act

FSM Free School Meals

GCSE General Certificate of Secondary Education

GM Grant-Maintained

LA Local Authority

LEA Local Education Authority

LMS Local Management of Schools

MAT Multi-Academy Trust

NAO National Audit Office

NPD National Pupil Database

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

ONS Office for National Statistics

OSA Office of the Schools Adjudicator

SEN Special Educational Needs

SES Socioeconomic Status

SIF Supplementary Information Form

SPSS Statistical Package for Social Sciences

SSFA School Standards and Framework Act

UK United Kingdom

UN United Nations

UTC University Technical College

VA Voluntary Aided

1

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Statement of purpose

This study emerged from an interest in the rapid expansion of the academies programme in England following the coalition government’s Academies Act of 2010. Forming an important part of this new legislation was the introduction of a new type of academy: Free Schools. Like academies, they would operate autonomously, outside of Local Authority control, and have freedoms in relation to their curriculum, budgets, staffing and admissions arrangements. But what was perhaps most significant about them was the fact that these schools would be newly-established institutions and would enable a broader group of stakeholders to become involved in the setting-up and running of schools.

This new policy initiative provides an interesting research context in itself. But the introduction of Free Schools also offers a significant extension of existing education policy, encouraging us to reconsider and develop our current understanding of issues related to school choice and the social composition of schools. When describing the rationale for the Free Schools initiative, policymakers pointed to improved standards, the extension of parental choice and the importance of increased diversity within the system (The Conservative Party, 2010; Gove, 2011). Whilst the standards agenda is, of course, important and of interest, it is the two latter motivations that were most influential in developing the focus of this current project. Previous research and some academic and media commentary had raised concerns about the impact of increased quasi-marketisation on access and opportunity for some of the

most disadvantaged pupils (Curtis et al., 2008; Hatcher, 2011; Millar, 2010; West et al.,

2009). Approaching the Free Schools policy through a social justice and equity lens, I wanted to explore the extent to which the new schools appeared to be serving poorer pupils and fulfilling their role of being “engines of social mobility” (Gove, 2011; Morgan, 2015).

The purpose of this research is to provide some in-depth, early insight in to the Free Schools initiative. It is designed to give an overview of the social composition of all of the Free Schools in the country and provide a comparison with other schools in their local area. But in addition to exploring this outcome of the policy, it was also important to explore mechanisms

2

which have previously been identified as influencing school intakes, particularly intakes that do not appear to include an equal share of disadvantaged pupils. As a result, both the behaviour of schools (via their chosen admissions arrangements) and the attitudes and actions of parents (in relation to the school choice process) formed an important part of this study. I wanted to know the extent to which the Free Schools were opting to use their admissions freedoms and the factors that encouraged parents to choose a brand new school for their child. These foci contribute to a fuller overall picture of the Free Schools initiative whilst also providing potential explanations for some of the findings relating to the composition of the schools. The findings from the study indicate some areas where measures could be taken to make the introduction of new schools more equitable. Significantly though, the findings also suggest that in many instances, Free Schools do not appear to be operating that differently to some other types of school. As such, it is important to retain a sense of perspective in relation to the Free Schools policy. There are still only a very small number of these schools in existence; they should not serve as a distraction for equity issues that exist more widely across the education system.

At the time of beginning this study, empirical research explicitly focusing on Free Schools in England was scarce due to the recent introduction of the policy. Since 2012, however, a small body of research has begun to emerge, particularly in relation to the composition of the schools, and the extent to which they are meeting their objective of providing education for

some of the most disadvantaged pupils (Green et al., 2015; Morris, 2015). There has also

been some focus on the experiences of those wanting to set-up new schools (Higham, 2014;

Miller et al., 2014) and some attempts to evaluate the effectiveness of the Free Schools in

comparison to other school structures (Porter and Simons, 2015). The limited existing research on Free Schools in this country pointed to the need for studies in this area to be undertaken. Moreover, it highlighted the need to examine a broader evidence base when considering the policy and research literature. As a result, both similar international models and key predecessor policies within the English education system have been explored. This thesis aims to add to this existing body of work but also seeks to provide alternative perspectives from which to understand the introduction of Free Schools. The in-depth focus on the schools admissions policies, the experiences of parents that have chosen a Free School

3

and the use of segregation ratios to compare intakes with those of other local schools all provide new and original contributions to the existing field.

1.2

Significance of the study

This research matters because debates surrounding school structures, autonomy and equity continue to play an important role in influencing government policy, just as they have done in previous decades. The Free Schools initiative does not simply provide another name for another new school ‘type’; instead, it has provided a real policy commitment to opening brand new schools across the country. Its introduction was viewed as a radical development in education reform and was met with strong debate from advocates and critics in its early years (Gilbert, 2010; Gove, 2011; NUT, 2013; Young, 2011). While Free Schools are viewed as an extension of the Academies programme (Gunter, 2011), both their recent introduction and their emergence as new institutions provide an important and novel context for research.

Ongoing equity and social justice concerns in relation to autonomous schools in England and internationally provide a further motivation for studying Free Schools. One of the key policy objectives was the provision of extra choice and educational opportunity for those from the most deprived backgrounds. Yet a body of research from this country and abroad has indicated that often autonomous schools tend to serve children from more affluent backgrounds and/or are linked to maintaining a segregated system (Allen and West, 2011;

Bunar, 2010; Gorard, 2014a; Kahlenberg, 2012; West et al., 2011). It is essential to establish

the extent to which Free Schools fit within this trend so that (i) there is awareness of whether policymakers are achieving their original objectives and (ii) equity issues can be highlighted and potentially addressed. At present the literature examining the Free Schools policy is small. When beginning to design this research, an initial investigation in to the intakes of the first 24 schools had been conducted (Gooch, 2011). However, there was no subsequent analysis of either the intake of first wave schools in later years or the intakes of further Free Schools established in following years. This suggested that a study which explored both the most recent composition data for all Free Schools and also tracked the intakes of the schools year-on-year could be beneficial.

4

Data on the representation of disadvantaged pupils in Free Schools provide a small part of the picture. I felt that there was also a need to try and understand some of the mechanisms that might be contributing to who was attending the schools and their reasons for doing so. The focus on admissions policies and specifically oversubscription criteria was one way of doing this. At the time of beginning this analysis and publishing the initial findings (Morris, 2014), no other systematic examination of the methods used by Free Schools to prioritise the allocation of places had been conducted. The same is also true of the investigation in to parents’ motivations and strategies for choosing a Free School. In a review of parental choice research, Gorard (1999) suggested that “unless there are major shifts in policy, producing an essentially new situation to research, it is unlikely that further work in this area will uncover new findings of great consequence…” (Gorard, 1999, p. 26). The introduction of Free Schools, I believe, can and should be viewed as a major shift in education policy, and one which does indeed produce a new and dynamic context to explore. There has been very little work done on parents’ experiences and attitudes towards selecting a recently-opened school, predominantly because historically, the opening of brand new schools occurs fairly infrequently and without the political force that has driven the Free Schools initiative. The emergence of Free Schools in their initial years, however, allows us to question whether the processes and strategies of parental choice alter when they are presented with this additional and unfamiliar potential option.

The aim of this study is to explore some of the issues linked to original concerns about the Free Schools policy. It is hoped that this research will provide both a useful reference point for understanding the early years of the initiative and a springboard for further research through the identification of key areas for subsequent study.

1.3 Research Questions

This research addresses the following objectives:

To illustrate the diversity of admissions arrangements and allocation methods

available and being used by new autonomous schools.

To examine the strategies and motivational factors that encouraged parents to

5

To provide an up-to-date summary and overview of the social compositions of all

Free Schools in England and to compare these with other local schools.

To explore the extent to which the Free Schools initiative has, so far, met one of its

policy objectives in relation to the provision of additional school choice, particularly for those from less advantaged backgrounds.

The first two objectives focus on two potential influences of school compositions: admissions arrangements and parental choice. The third objective relates very much to an ‘overview’ perspective. It seeks to establish first of all, whether there appears to be the unbalanced intakes in Free Schools that a number of commentators were concerned about, and that some researchers highlighted in very early examinations of the first wave of schools (Gooch, 2011). It is also focused on tracking the school intakes over time and beginning to establish a more developed description of how the compositions of the new schools compare with others in their local area. Finally, drawing on the previous three objectives, I consider whether the Free Schools policy does appear to be providing equality of educational access and opportunity to those from less advantaged backgrounds, and the potential impact that this may have on the wider schools system should the initiative continue to expand.

The overarching question which forms the central focus for this study is: ‘Who attends English Free Schools and why?’

The specific research questions used to address the objectives above are as follows:

What allocation methods are Free Schools choosing to use in order to prioritise

their available places?

Why (and how) do parents choose a newly-opened Free Schools for their child?

Are Free Schools taking an ‘equal share’ of socially disadvantaged pupils?

1.4

Overview of design and methods

The opening of new schools has created scope for a comparison of the behaviours and outcomes of Free Schools with other state providers. For a researcher, it is straightforward to establish Free School and non-Free School groups as detailed information on this is publicly available (see for example, DfE, 2015b). The introduction and distribution of Free Schools

6

across England, however, is not random and nor are the intakes of pupils that attend them.

The study relies, therefore, on determining these groups after the schools were opened. As

stated above, developing our knowledge of how this new policy initiative is functioning in its own right is important but it is arguably even more important that we understand how it fits in with the wider, established schooling system. In order to address this and to respond to the research questions, three quite distinct studies were designed, each using different data collection methods. The structure and method of data collection for each section was very much informed by each of the research questions (Gorard, 2013). Despite the questions being addressed separately, each section was treated as a component part of the overall study, with the aim being to address the overarching research question from different angles.

Table 1.1 gives an overview of each of the research questions with the selected data collection methods.

Table 1.1: Research questions and data collection methods

Research Question Data Collection Method 1 Data Collection Method 2

What allocation methods are Free Schools choosing to use in order to prioritise their available places?

Documentary analysis of all secondary Free School admissions policies. Comparison with admissions policies of LA-maintained schools.

Why (and how) do parents choose a newly-opened Free School for their child?

School choice questionnaire for parents of Year 7 children attending Free Schools and non-Free Schools.

Interviews with parents of Year 7 children attending a secondary Free School.

Are Free Schools taking an ‘equal share’ of socially disadvantaged pupils?

Annual Schools Census data on all Free Schools in England (2011-2014). Comparison with six geographically nearest schools and LAs.

The findings in relation to each research question are presented in separate chapters. Where appropriate, links between the findings are also considered. A more detailed account of the methods used for data collection and analysis can be found in Chapter 5.

7

1.5

Theoretical framework

Many recent social policy reforms (including those in education, welfare, social care and housing) have been introduced as the result of political and economic commitments to a more

market-based system (Adnett and Davies, 2002; Gorard et al., 2003; Powell, 2003). In

relation to schooling, this has led to an ideological interest in the provision of diversity and choice, permitting parents to have more individual power over the type of education that they would prefer for their child. In addition, increased competition, privatisation and autonomy have become more central features of the education system, developed as a result of powerful neo-liberal political influence over the last three decades. This study focuses on a policy initiative which when introduced was very much understood to represent a further shift towards marketization within the schooling system (Allen, 2010a; Hatcher, 2011). Free Schools were not simply about tackling demand-side issues and the provision of additional parental ‘choice’; they were also focused on developing a more dynamic supply-side, allowing a wider range of interested parties to be involved in encouraging new entries to the market.

The free market analogy provides a helpful lens through which to view recent policy reforms but it is problematic in that it does not sufficiently consider the state-funding and regulation that remains within public service provision. Instead the term ‘quasi-market’ (Le Grand and Bartlett, 2003) is deemed a more useful description and has been adopted by a number of commentators and academics interested in market-oriented education policy (e.g. Exley,

2012; Gewirtz et al., 1995; West and Pennell, 2002). Bartlett and Le Grand (2003) outlined

four criteria for evaluating the impact of quasi-market reforms in social policy: efficiency, responsiveness, choice and equity. This study is particularly concerned with the role of equity in the Free Schools policy and how this is linked with the behaviour of both schools and parents. There are economic arguments that indicate both the positive and negative impact that market-reforms in education potentially have on equity. Some suggest that they are preferable to a public monopoly system as children are not confined to attending a designated ‘catchment’ school irrespective of its quality. Advocates argue that this is likely to reduce ‘selection by mortgage’ and the stratification that occurs as a result. Diversity within the system also has the potential to allow more parents the freedom to choose the type of schooling that best fits the needs and interests of their child (rather than just those who can

8

afford to pay for diversity offered via the private system) (Chubb and Moe, 1990). By contrast, some economic theory suggests that a market-system is likely to disadvantage some groups, specifically those from lower-income backgrounds. There are concerns regarding the potential for schools in a competitive market to ‘cream-skim’ more advantaged pupils and

increase segregation (see Allen et al., 2014; Epple and Romano, 1998; West et al., 2006).

In addition to the economic arguments, a body of sociological work has sought to examine the impact of market reforms in school systems. This work has predominantly focused on the role that social class plays in shaping parents’ choices and suggests that parents from different

class backgrounds engage in the choice process in different ways (Ball, 2003; Gewirtz et al.,

1995). The notion of ‘middle class advantage’ plays an important role, particularly in relation to the amount of capital (financial, social and cultural) that parents have available to them and the influence that this has on the decision-making process for different groups. Academics in this field have argued that this leads to a situation of social reproduction within the schooling system, whereby those from lower socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds are persistently disadvantaged (Ball, 2003).

Previous work on school choice reforms has seen economic and sociological perspectives dealt with fairly separately. In the current study both approaches have been drawn on as it is felt that they each have something to contribute in relation to examining and understanding the mechanisms that are contributing to equity (or indeed inequity) within the current school system. These issues are discussed further in Chapter 3.

1.6 Scope of the study and limitations

This subsection outlines and justifies the scope of the current study. When designing this research, I was keen to try to gain a broad picture of the Free Schools policy. It was important to know where and how the Free Schools were ‘fitting in’ with the wider schools landscape. As a result of this I felt that it was necessary to examine the social compositions of all of the mainstream Free Schools across the country as well as considering how these compared with other schools in their local area. Access to the Annual Schools Census data made this very practical and also allowed for the tracking of intakes year-on-year. The findings from this part

9

of the study provide a valuable dataset which allow us to consider Free School intakes at a national, local and school level (Morris, 2014).

With regard to the study of Free School admissions policies, I took the decision to examine all of the mainstream secondary schools that had opened. Concentrating on secondary school

admissions is in line with earlier studies in the field (White, 2001; West et al, 2009, 2011) and

allows for a clear focus on the important transition between primary and secondary school. It is acknowledged that in studying just the secondary policies that some relevant and important examples of admissions arrangements used by the primary sector could have been missed. Examination of these could form part of a useful wider study in the future.

My concerns regarding scope though are most relevant to the parental choice part of this study. When developing this aspect of the research I began with very extensive plans of the number of schools and parents that I wanted to include in the study. A combination of practical issues (such as the cost of printing questionnaires, posting them and paying for Freepost envelopes) and relatively low numbers of willing participants meant that I had to adjust my expectations. By the end of the data collection period 346 questionnaires were returned (139 from Free School parents and 207 from non-Free School parents) and 20 Free School parents were interviewed. While fewer than I had hoped for, I still feel that I have been able to collect some original and valuable data which have provided important insights in to the motivations and strategies of school choice in relation to the Free Schools context. The findings have also been very useful in pointing to areas which would benefit from further, more in-depth study.

1.7

Structure of the thesis

The study is divided in to four main sections. These are:

Literature review

Design and methods

Findings and discussions

10

The first part consists of three chapters. These explore the theoretical, policy and research literature in relation to the introduction of the Free Schools initiative. The first chapter provides a timeline of policy developments and reforms which have led to Free Schools entering the ‘market’. The second chapter focuses on placing the Free School policy within a theoretical context, drawing on both economic and sociological perspectives to do so. The final chapter reviews the relevant empirical research linked to the composition of schools and segregation, school choice and admissions arrangements.

The second part describes the design and methodological decisions that were made in relation to each part of the study. The section makes clear links between the research questions and the selected research methods. It also discusses the creation of the data collection instruments, the limitations associated with the chosen methods, and gives some contextual information in relation to the schools and parents that participated in the study.

Part three consists of three main subsections, each of which presents the findings and discussion in relation to one of the research questions. The first looks at the data from the analysis of admissions arrangements. The second reports the findings relating to parental choice of a Free School. Finally I focus on the presentation of findings relating to student composition at the Free Schools. Each subsection also considers the data in light of the relevant policy and research literature. Where appropriate, links between the findings and different data sets are presented in order to build-up a clearer overall picture of the Free Schools policy.

The final part of the thesis draws together all of the findings to provide a response to each of the original research questions. The conclusions consider where this study ‘fits’ within the wider research and policy context but also acknowledges that its scope is somewhat limited, and that there are a number of areas which would benefit from further research. Recommendations focusing on the Free Schools policy, and on schools policy more broadly, are also included.

11

CHAPTER 2

POLICY BACKGROUND

2.1 Introduction

This chapter summarises key policy developments in English school-based education, mapping the route to the introduction of Free Schools in 2010. The trajectory towards market-oriented social policy that has been especially dominant in England over the last thirty years is discussed, making it clear that the Free Schools initiative has not simply appeared ‘out of nowhere’. This policy review takes the election of a Conservative government in 1979 and the subsequent 1980 Education Act as its starting point. Some of the key issues linked to choice, diversity and the reduction of local government control can, of course, be tracked back even further in history (see for example, Benn and Chitty, 1996; Jones, 2003 for a detailed discussion). The opening section briefly explores policy reforms between 1979-1997. A second subsection considers the developments introduced during the 13 years of a New Labour administration, and a final section discusses the most recent policy reforms following the election of Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition in 2010. This concludes with an overview of the features of the Free Schools policy and the rationale for its introduction.

2.2 Conservative government schooling reforms (1979-1997)

Within the context of economic recession in the early-mid 1970s, some policymakers reassessed the purpose of schooling and sought to challenge “the dominant ethos of personal development and promoted in its place the vocational preparation of young people for their future economic roles” (Ranson, 1990, p. 6). By the end of the decade, the comprehensive model had become a target for ongoing criticism in relation to academic standards, curricula, discipline and the control held by LEAs (Denscombe, 1984; Ranson, 1990). The politics of the New Right instead emphasised a school system based on the fundamental principles of public choice, accountability and individual control, values that were to underpin much of the education policy of the 1980s.

The 1980 Education Act also began to formalise an increased role for parental choice, allowing parents to state a preference for an alternative to their designated or ‘catchment area’ school. Alongside this, LEAs were compelled “to show why a parent's preference for a school

12

should not be satisfied” (DES, 1992, p.4) and ensured that appeals committees were established to hear parents’ cases. Whilst some highlight the limited amount of change that occurred in relation to choice and admissions in the early years of the new Conservative administration (Benn and Chitty, 1996; Stillman and Maychell, 1986), the government’s desire to shift power away from LEAs and towards parents had been firmly established (Stillman, 1986).

A focus on parental choice continued to be one of the key features of the heavily debated 1988 Education Reform Act (ERA). The Act legislated more radically than any since the Butler Act in 1944, enshrining many of the principles of marketization and seeking to apply them to a state-funded social schooling system. The Act limited the power of LEAs, diminishing the their controls hover funding and allocation procedures. Local Management of Schools (LMS) meant that schools could be taken out of LEA financial control and budgetary powers could be given directly to the headteacher and governors of individual schools. Closely linked to the issues of financial and bureaucratic autonomy was an emphasis on further development of parental choice. With school budgets largely determined by pupil numbers, schools were encouraged to compete for pupils in order to maximise their funding. This competition was increasingly possible due to the system of open enrolment that had been introduced. Parents were allowed to state preferences for any chosen school with schools only being able to reject applicants if they were physically full. The creation of Grant-Maintained (GM) schools was also with a view to increasing parents’ choice and reducing the role of the LEA (Rogers, 1992). Maintained schools could apply to ‘opt out’ of LEA control, and become GM and as a result received a financial incentive and had control over their own budgets and admissions/allocation procedures. Education Secretary, Kenneth Baker, stated that GM schools would “provide a standard of excellence and will be beacons” (Baker, 1989,

no page). Some commentators, however, were concerned that the development of diversity

through new ‘types’ of school had the potential to encourage a hierarchy between schools, one where LEA-controlled, community schools were perceived as having the lowest status (Flude and Hammer, 1990).

This desire to increase diversity within the schooling system and present a further challenge to LEA provision was also evident through the introduction of the City Technology College

13

(CTC) programme. CTCs were to be brand new schools and were presented as a bridge

between the state and independent sectors (Whitty et al., 1993). Like GM schools, they would

operate independently of the LEA but would be funded jointly by the government and sponsors from the industry and business sectors. They would also have control over their own admissions and were allowed to be selective (DES, 1986). One of the defining features of CTCs was their curriculum freedom. The 1988 ERA had introduced, for the first time, a National Curriculum to be followed by all state –maintained schools in the country. CTCs’ independent status meant that they were less bound by this although were still broadly required to adhere to it as a condition of funding (Ranson, 1990; Walford and Miller, 1991). Despite attempts to promote difference between CTCs and other schools, and the technology specialism of CTCs, initial studies showed that they offered largely similar programmes of

study and pedagogy to other state-funded schools (Walford and Miller, 1991; Whitty et al.,

1993). There had been ambitious plans to open many CTCs across the country (Benn and Chitty, 1996). However, between 1988-1993 only 15 CTCs opened, primarily due to a lack of sponsorship funding from the business and industry partners that had been approached by the

government (Rogers, 1992; Whitty et al., 1993). The programme was subsequently

abandoned and the government turned their attention to the introduction of the specialist schools policy where some schools could be designated as having a technology specialism.

In 1993, the Conservative government introduced another initiative in an attempt to stimulate the supply-side of an increasingly marketised system. Sponsored grant-maintained schools were designed as a way to deliver further diversity to meet reported parental demand (Walford, 2000a). The policy allowed sponsors to propose brand new schools or re-establish existing faith or independent schools as grant-maintained institutions. Unlike previous GM schools, those groups wishing to invest in a sponsored GM school were required to “pay for at least 15% of costs relating to the provision of school buildings” (Walford, 2000a, p. 148). As a result, sponsors could preserve the original religious designation and objectives of the school. Where attempts to establish new faith schools had previously gone through LEA procedures, instead applications for sponsored GM schools went straight to central government. Like the CTCs programme, however, the initiative floundered and only 15 sponsored GM schools opened. Walford (2000a) argues though that this failure was not due to a lack of willing sponsors but instead because of the demands of the application process. The

14

symbolic gesture of allowing religious minorities to open and run their own state-funded schools was the more significant result of the programme, paving the way for subsequent governments to encourage more faith schools within the maintained sector (DfES, 2001; Walford, 2000b).

2.3 The New Labour Years (1997-2010)

2.3.1 Changes and continuation of Conservative policy

For many supporters, the Labour party’s landslide victory in 1997 signalled radical change for education policy. Pre-election, the Labour manifesto stated that the party would:

…put behind us the old arguments that have bedevilled education in this country. We reject the Tories' obsession with school structures: all parents should be offered real choice through good quality schools, each with its own strengths and individual ethos. (The Labour Party, 1997, no page) But those who hoped that the election would signal the end of market-driven reforms were left disappointed.

While suggesting a move away from Conservative attempts to create new types of school, there remained a focus on the issue of parental choice and schools providing this through the delivery of ‘something different.’ The continued promotion of choice and diversity endured throughout the New Labour years with a strong belief that the market had an important role to play in raising standards and meeting parental demand (Adonis, 2012; Blunkett, 2001). Alongside this message though was an additional focus: social equity (West and Pennell, 2002). New Labour were keen to abandon previous Conservative policies that may have been perceived as maintaining elitism and instead framed their reforms in the language of inclusion and social justice (Brown, 1999; Powell, 2000).

The Assisted Places Scheme was abolished within Labour’s first year in office, breaking the link between state-funded and independent schooling, and ending a Conservative policy

which opponents argued only benefitted a minority of children (Fitz et al., 1986). The 1998

15

demonstrated their commitment to ‘difference’ between schools by creating new names for each type. ‘Local authority’ schools were renamed ‘community’ schools and those which had previously held GM status generally became known as ‘foundation’ schools. Faith schools and some GM schools were termed ‘voluntary’ schools under the new legislation. Notably though, these schools still remained as their own admissions authorities and many GM

schools continued to gain additional ‘transition funding’ (West et al., 2000).

The Labour Party’s drive for differentiation between schools was also made evident through the continuation and expansion of the specialist schools programme. This had been launched by the previous Conservative government in 1994 and had allowed GM or VA schools to operate as technology colleges. In the following two years language, arts or sport were added

as possible specialisms (Schagen et al., 2002). Achieving ‘Specialist School’ status was

conditional on securing £100,000 (£50,000 from September 2000) of private sponsorship which would be matched by a government grant and an increase in their regular state funding.

To further diversify the system, new potential specialisms were added in 2001. These were: science, engineering, business and enterprise, mathematics and computing. By 2010 there were 3,068 specialist schools in England, approximately 93% of the total number of state secondary schools in the country (DCSF, 2010). Whilst it was claimed that the programme was successful in raising standards and improving attainment (DfES, 2001; Jesson and Crossley, 2006), others criticised the methods used to draw such conclusions (Goldstein, 2001) and highlighted other factors that may have positively affected achievement within

specialist schools (Gillmon, 2000; Pugh et al., 2011; Schagen et al., 2002; West and Pennell,

2002). In short, it seems unlikely that improved standards could reliably be attributed to specialist status alone (BBC, 2007; Gorard and Taylor, 2001).

The impact of the specialist schools programme on social justice and equity was also a concern. Some researchers argued that the schools served to reinforce a hierarchy of status and in some cases, their admissions and allocation procedures were not equitable (Gorard and Taylor, 2001; West and Pennell, 2002). Permitting specialist schools to admit 10% of students based on aptitude was highlighted as a potentially unfair allocation method as the problems of differentiating between ability and aptitude meant that selection could be based on social

16

factors (West and Ingram, 2001). Other researchers questioned the supposed link between diversity and choice, suggesting that for many families the new specialism ‘labels’ attached to schools meant very little (Castle and Evans, 2006), and could even appear to limit choice if the specialism was not one of interest (Smithers and Robinson, 2009).

2.3.2 Admissions and allocation procedures

In their 1997 election manifesto, the Labour party stated that they wished to improve the application and admissions process, making it fairer and more transparent (Labour Party, 1997). This was a response to growing concern about the administration and equity of allocation procedures, particularly since the introduction of policy which had allowed many

schools to have control over their own admissions. Gewirtz et al. (1995) present examples of

different methods that schools used to covertly select more affluent or academic pupils. West and Pennell (1997) also argue that the increased fragmentation of the overall school system meant that there was limited impartial advice available for parents regarding admissions and that there was little regulation to prevent ‘cream skimming’ or selection of certain groups of children. As a response to such concerns, the 1998 SSFA outlined a new legal framework for admissions alongside a revised Code of Practice (DfEE, 1999). In an attempt to reduce the potential for schools to ‘select in’ or ‘select out’ certain groups of pupils, the Code of Practice stated that in secular schools there should be no parent interviews conducted prior to the allocation of places. In religious schools, interviewing would be allowed to continue but only to establish a family’s denomination and assess religious commitment (DfEE, 1999). The code also introduced the role of an adjudicator with the aim of reducing admissions disputes at a local level. In addition, the adjudicator also had the function of preventing any new attempts to use selective methods other than permitted ability banding (DfEE, 1999). Studies focusing on these policy changes reported some positive outcomes in terms of LEAs regaining some of their control over admissions and therefore being able to provide a more

coordinated and equitable system (Fitz et al., 2002; West and Ingram, 2001). Despite this,

both sets of authors concluded that there was still more that could be done to make the application and admissions processes fairer for all families.

17

2.3.3 The Learning and Skills Act 2000: introduction of the first academies

In March 2000, Education Secretary, David Blunkett announced the introduction of the first City Academies (BBC, 2000; Carvel, 2000). Whilst the Labour government maintained that their establishment was about improving standards in some of the poorest areas of the country (Blunkett, 2000), critics argued that the government were reverting to the Conservatives’ focus on school structures, introducing another type of school that was reliant on sponsorship from businesses and allowed to operate independently of the LEA (Beckett, 2000).

City Academies were to be non-fee paying schools, replacing failing or underachieving secondary schools in urban areas in England. Business, church or community sponsors were required to pay £2 million towards the set-up and running of the school with the rest of the funding coming directly from central government. Blunkett (2000) stated that the schools would form part of a wider drive towards diversity in the education system, claiming that the government “do not have a single blueprint for these Academies, and will be responsive to proposals from sponsors in each case” (Blunkett, 2000, no page). The Labour government had sought diversity through their rapid expansion of the specialist schools programme but failing schools had not been allowed to be part of this; the academies programme was designed to change this. The independence that the schools would be afforded would, Blunkett argued, “offer a real change and improvements in pupil performance, for example through innovative approaches to management, governance, teaching and the curriculum, including a specialist focus in at least one curriculum area” (Blunkett, 2000, no page). As with City Technology Colleges before them, the first academies were to have significant freedoms in their curriculum, staffing, budgeting and admissions. It was believed that these freedoms, coupled with the ‘fresh start’ approach of the academies programme would lead to the schools producing considerably better outcomes than those which they had replaced.

The first three City Academies opened in 2002. Nine more opened in 2003 and a further five in 2004. The term ‘city’ was dropped from the name in 2002 with the intention of academies opening all over the country, not just in large, urban areas. The government set themselves a target of opening 200 sponsored academies by 2010 (DfES, 2004) and sponsors were keen to report the early successes of the programme (BBC, 2004). However, claims that academies produced better results than their predecessor schools were questioned (Gorard, 2005; 2009a)

18

and a five year evaluation of the policy concluded that there was “insufficient evidence to

make a judgement about the Academies as a model for school improvement” (Armstrong et

al, 2009, p. 123). There were also concerns that the schools being selected for academisation

were not the ones most in need of it (Gorard, 2009a). Significantly, there was evidence that the composition of academies was altering over time, resulting in a decrease of poorer pupils attending although, on average, they still took more disadvantaged children than other types

of secondary school (Curtis et al., 2008).

By the time of the general election in May 2010, there were 203 sponsored academies open in England. Despite the growth of the policy and reports of some notable successes (Bedell, 2008), there was still some opposition to academisation. Commentators expressed concerns about, amongst other things, their effectiveness and cost, their ability to be selective and the lack of LA oversight (Ball, 2005; Hatcher, 2009; NUT, 2007). Nevertheless, both major political parties expressed full support for the academies programme, with both wishing to expand it further (The Conservative Party, 2010; The Labour Party, 2010).

2.4 The Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition and the expansion of the

academies programme (2010-present)

2.4.1 Introduction of converter academies

In the White Paper The Importance of Teaching, the coalition government praised the

successes and innovation of CTCs and the original academies, but criticised the limited ambition of the early sponsored academies programme. As a response they argued that the academies initiative should be significantly expanded and available to all schools (DfE, 2010). Autonomy from local and central government control was perceived as a vital component of an improved school system, with policymakers suggesting that schools would use this independence to improve standards and narrow the attainment gap (DfE, 2010; Gove, 2010).

Table 2.1 shows the number of academies in England and highlights the rapid expansion of the policy following the general election in 2010. The new type of academy schools became known as ‘converter academies’ and their introduction was formalised in the Academies Act 2010.

19

Table 2.1: Number of sponsored and converter academies open in England

Year Sponsored Academies Converter Academies Total

2002/03 3 0 3 2003/04 9 0 12 2004/05 5 0 17 2005/06 10 0 27 2006/07 20 0 47 2007/08 36 0 83 2008/09 50 0 133 2009/10 70 0 203 2010/11 71 529 803 2011/12 93 1058 1954 2012/13 366 731 3051 2014/15 304 445 3800

Source: DfE (2015a) and DfE (2016)

Originally, schools which had been graded ‘Outstanding’ by Ofsted were prioritised for conversion. This was later relaxed so that all schools that were performing well could apply to convert (DfE, 2011a). Schools with lower performance could apply for academy status if they agreed to a partnership with an ‘Outstanding’ school (DfE, 2012a). The table above shows the number of sponsored and converter academies open between 2002-2014. The government also remained committed to the sponsored academy initiative, expanding it for secondary schools and allowing primary and special schools to join the programme. By January 2015, 60% of England’s secondary schools and 15% of primary schools held academy status (DfE, 2015c).

2.4.2 Free Schools

The 2010 Academies Act also legislated for another key Conservative party election pledge: the setting-up and opening of two new types of schools: Free Schools and University Technical Colleges (UTCs). At the time, these policies formed an important part of the Conservatives’ ‘Big Society’ ideology (Cameron, 2011) – a belief that the state had become too controlling and that private sector and individual interests should be actively addressed and promoted via decentralisation (Higham, 2014). Free Schools would provide the

20

opportunity for sponsors such as parent groups, teachers, businesses, charities, faith groups and academy trusts to propose and run new institutions. UTCs would be set-up by universities and businesses to provide education for 14-19 year olds. The rest of this section predominantly focuses on the introduction of Free Schools. For more on UTCs, see Fuller and Unwin (2011).

The new, autonomous Free Schools were based on similar models in Sweden and America (The Conservative Party, 2010; DfE, 2010) and could provide mainstream or special education. A small number of private schools have also opted to convert to Free School status and in doing so, must no longer charge fees for attendance. The DfE also encouraged sponsors to open new alternative provision institutions for children struggling to stay in mainstream schools (DfE, 2010).

Free Schools, as a type of academy, operate outside of Local Authority control, with some increased freedoms over budgets, staffing, curriculum and admissions. As with the converter academies initiative, Free Schools were expected to use their freedoms to improve standards and increase parental choice (Gove, 2011). In addition, the government argued that Free Schools would: improve the quality of schools in deprived areas, provide additional school

places and encourage parental responsibility for children’s education (DfE, 2010; Miller et al.,

2014). Perhaps most significantly though, the schools were to be brand new institutions, signalling a clear attempt to liberate the supply side of school provision and symbolising the government’s commitment to extending choice and diversity within the system.

The table below shows the number and type of Free Schools that have opened in each year since 2011. Like academies, Free Schools only exist in England rather than across the whole of the UK. In their 2015 general election manifesto the Conservative Party pledged to open a further 500 schools by 2020 (The Conservative Party, 2015).

21

Table 2.2: Number of Free Schools opened each year

Year Mainstream Special Schools Alternative Provision Total

2011/12 24 0 0 24 2012/13 48 3 5 55 2013/14 75 5 13 93 2014/15 65 3 10 78 2015-To date 41 8 4 53 Source: DfE (2015b)

Following its introduction, there was strong support for the Free Schools policy from some academics and high-profile sponsors (Sahlgren, 2010; Young, 2011), and a number of established academy chains opted to open new schools within the first wave (BBC, 2011). Since the introduction of the policy, however, concerns have been raised by a number of academics and commentators. These have included concerns regarding the equity of the policy, school quality and whether there is demand for some of the new schools. The main issues are outlined below:

Concerns that Free Schools would receive funds that had been diverted from other

schools (Millar, 2010) or that Free Schools would receive more per-pupil funding than other schools (Mansell, 2015).

New schools not being planned for or situated in areas with a ‘basic need’ for school

places (NAO, 2013).

The belief that Free Schools would predominantly be located in more advantaged

areas where parental demand for them was highest (Vasagar and Shepherd, 2011).

A lack of local oversight for LAs, making it more difficult to plan for future school

places provision (Hatcher, 2011).

A concern that via their admissions freedoms, Free Schools would be able to ‘select

in’ pupils with certain characteristics, leading to less balanced intakes across and negatively impacting on the student compositions of other local schools (Vaughan, 2010; West, 2014).

The ability for Free Schools to use unqualified teaching staff (NUT, 2013; Vaughan,

22

Fears that despite government requirements that all schools must deliver a broad and

balanced curriculum, the policy could give some schools too much freedom and allow the promotion of particular religious or fundamentalist agendas of their sponsors (Hawley, 2014; Vasagar, 2012b).

Some have also questioned the government’s effectiveness argument, suggesting that similar reforms in Sweden and America had not led to the definitive academic success that proponents claimed (see Allen, 2010a; Hatcher, 2011; Wiborg, 2010). Whilst the Department for Education have attempted to refute such claims and publicise successes within the Free Schools programme, most schools have not been open long enough to receive examination data on which to base objective effectiveness measurements. To date, researchers have been particularly interested in a number of the social justice issues, including the experiences of

proposers (Higham, 2014; Miller et al., 2014), their admissions arrangements (Morris, 2014)

and student compositions (Green et al., 2015; Morris, 2015). The findings from these studies

and others are discussed in more depth in subsequent sections.

This chapter has summarised the key policies and legislation that have paved the way for the recent introduction of the Free Schools programme. I now turn to the theoretical literature linked to the introduction and development of market reforms in social policy, specifically those relating to education.

23

CHAPTER 3

FREE SCHOOLS: A THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

3.1 Introduction

This chapter provides a theoretical context within which to view the introduction of Free Schools in England. It outlines how the development of market-oriented education policy described in the previous section has formed part of a wider trend in public service reform over the last three to four decades. This has seen significant developments in the provision of not just education, but also health care, social care and housing (Le Grand, 2011). Whilst such changes have predominantly occurred in more developed countries such as America, the UK, Australia and New Zealand (Heyneman, 2009), more recently similar systems in countries

such as Colombia and Pakistan have been emerging (Morgan et al., 2013).

This chapter examines market-based reforms in education and discusses the concept of ‘quasi-markets’. The criteria and conditions outlined by Le Grand and Bartlett (1993) for evaluating the potential success of quasi-markets are also considered. The final section discusses the theoretical rationale and critiques of the recent introduction of Free Schools in England.

3.2 Monopoly public schooling

Economists have long regarded public monopolies as beset with considerable inefficiencies (Chubb and Moe, 1990; Shleifer, 1998). Critics argue that within a democratic monopoly there is no direct link between the funding that schools receive and the outcomes and satisfaction of those utilising them (Chubb and Moe, 1990; Friedman and Friedman, 1982).There is, therefore, no incentive for those running the school to improve or increase levels of parent or pupil satisfaction. As a result, it is believed that the schools operate solely in the interests of those working in them, with attempts to reform being tightly controlled by managers and unionised teachers (Hoxby, 2003). Even if schools did have a desire to improve, some argue that the bureaucratic control of political and administrative authorities stifles this through mechanisms of financial control, regulation and management of the admissions process (Chubb and Moe, 1990).