Social and unemployment insurance:

a comparative analysis for Europe

Content of the module

• Unemployment insurance: a comparative analysis for

Europe.

• Introduction to job search theory.

• Job search theory and unemployment insurance.

• Optimal unemployment insurance.

• Unemployment insurance: empirical evidence on its

effect.

Public Economics and Labour Markets

• Public economics deals with government

interventions in the economy.

• Public economics tries to explain from an economic

point of view:

- Why governments should intervene in the economy

Reasons of interventions

• Among the reasons for government intervention

there are:

1) Market Failures (Externalities, Public goods

etc…).

Public Economics and Labour Markets

• Government should interve in the working of the

labour markets:

- For redistributive reasons (transferring money to

workers earning too little or nothing).

- To correct market failures that could be present in

Money to unemployed workers

• Consider now a policy consisting in giving money

to unemployed workers.

• Can this be motivated from from a public

Money to unemployed workers

• Giving money to unemployment can be motivated

for redistributive reasons but also because of market failures.

• In this latter case the reasons for market failure

comes from problems of asymmetric information and moral hazard.

Asymmetric information, moral hazard

and unemployed workers

• A government can give money to unemployed workers to help him facing an unexpected period of time when he cannot find a job.

• But, alternatively, the worker could have obtained a private insurance to cover him in case of unemployed.

• That is, the worker could go to a private insurance company, pay them an amount each months and in

exchange get back a larger amount of money if he lose a job.

• If this is the case, the market can take care of the problem of unemployment and public intervention is not needed

Asymmetric information, moral hazard

and unemployed workers

• However a private insurance against unemployment

can hardly exists because of:

• Asymmetric Information: the insurance company

does not know exactly the quality of workers and does not know the probability that he lose the job (while

workers knows this information).

• Moral Hazard: once the worker has a private

insurance against unemployment his behaviour will change. He will put effort in the job (increasing the probability of being fired) and, in particular, once he becomes unemployed he will put less effort in finding a job (given that he is paid to be out of work!).

Asymmetric information, moral hazard

and unemployed workers

• Given Asymmetric Information and Moral

Hazard the private sector cannot provide an

insurance against unemployment and therefore the public sector should intervene to create a public

insurance against unemployment or some other transfer of money to people out of work.

Topics of this module

• Unemployment insurance: a comparative analysis for

Europe.

• Introduction to job search theory.

• Job search theory and unemployment insurance.

• Optimal unemployment insurance.

• Unemployment insurance: empirical evidence on its effect

Social Insurance, Unemployment Insurance

and Social Assistance

• Social insurance: it is an insurance that workers

pay to some public institutions and that covers them in case of some events (usually illness, accidents, old age, unemployment and so on).

• Unemployment insurance: it is an insurance that

workers pay to some public institutions and that covers them in case of unemployment.

• Social assistance: it is an amount of money that the governments transfer to individuals. It is not an

insurance and these individuals did not pay anything to receive it.

Social Insurance, Unemployment

Insurance and Social Assistance

• In this module we focus on unemployment

insurance (and not much on social insurance in general).

• We will cover several aspects of unemployment

benefits: practical, theretical, empirical and comparative

Unemployment insurance

• Unemployment insurance systems consist in a

mechanism that pays amounts of money (benefits) to certain individuals when they are unemployed.

• UI systems are usually made up of an infrastructure

UI building blocks

• Eligibity requirements:

• In order to be eligible to receive benefits workers must

satisfy some eligibility requirements.

• Often they are in the forms of previous months/years

of employment and of contribution to some welfare funds.

• This, in general, prevent new entrants in the labour

market to be eligible for benefits.

• If the system did not require any previous

contribution it is not exactly structured as "insurance" but rather as "assistance"

UI building blocks

• Requirement during benefits reception

• Workers on benefits are otfen asked to mantain

some behaviour during this period. Failure to mantain such compulsory behaviour should imply the suspension or termination of the benefits.

• Typical examples can be the requirement of active

search (unemployed must prove to be actively searching for a job), of attending training courses and the obligation of not refusing job offers.

UI building blocks

• Employement servicses during reception

• Workers on benefits are usually offer some employment

services during this period. In particular they are generally offered:

• Counseling through several interviews with job counselor

that advise them how to better search for a job.

• Direct offers of jobs that appear to be suitable for the

worker.

• Training course to enhance the skills and the

employability.

• A personal plan which describe in details the course of

action to follow in order to improve employability.

• All this activities are in general carried out by public

employment centre (even if private alternatives are sometimes offered).

UI building blocks

• Amount paid as benefits

• The actually amount paid is usually computed as a

percentage of last wage (or an average of wages

during the last few years). A ceiling to the benefits is usually also added.

• In general benefits are taxed at the normal rate

and in some cases (but not always) contains pension contribution.

UI building blocks

• Maximum duration

• Benefits usually have a maximum duration in

months/years after which benefits expires and workers stop receiving them.

• In some case duration also affect the amount

received: benefits amounts decrease through duration.

• Maximum duration usually depend on workers age

(older get longer benefits) and on how long the

A comparison of European UI system

• We compare systems on two dimensions:

• The generosity of the system (amounts and

duration)

• Active Employment Services and Search

Requirements (how the unemployed is helped in finding a job and how stringent are the search

1. PART B. THE EMPLOYMENT AND SOCIAL POLICY RESPONSE TO THE JOBS CRISIS

OECD EMPLOYMENT OUTLOOK – ISBN 978-92-64-06791-2 – © OECD 2009

76

A simple way of summarising many of the relevant institutional details is by means of

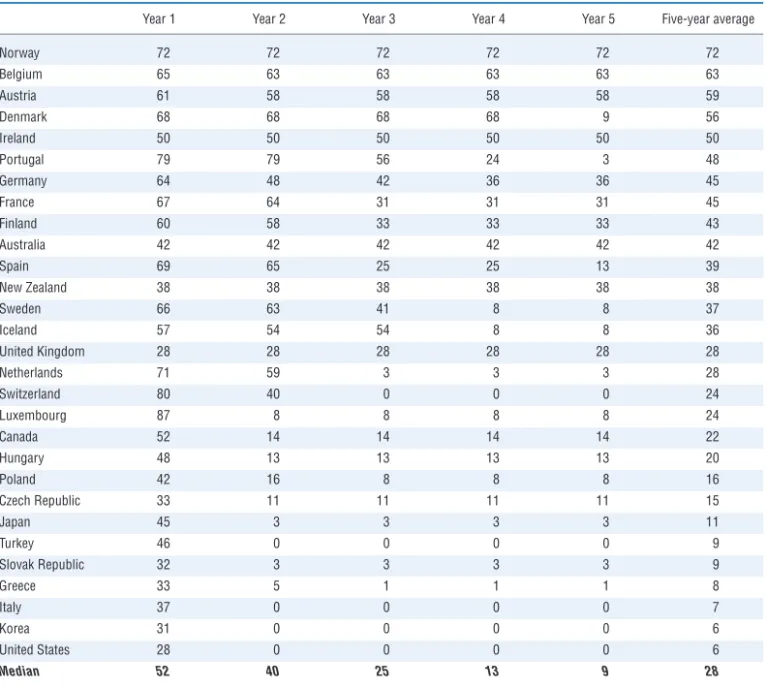

benefit replacement rates, which express net income of a beneficiary as percentages of net income in the previous job.76 Unemployment benefits are the “first line of defence” for those experiencing a job loss. Table 1.6 shows benefits replacement rates at different stages during an unemployment spell for prime-age individuals (Annex Tables 1.A8.1 and 1.A8.2 in OECD, 2009e show net replacement rates for younger and older workers). Results are averages over different earnings levels and family situations and account for taxes and for family-related benefits that are typically available. They refer to 2007 and, thus, to a period before any adjustments were made in response to the current downturn. In order to

Table 1.6. Generosity of unemployment benefits

Net replacement rates at different points during an unemployment spell, 2007a In percentage

Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Year 5 Five-year average

Norway 72 72 72 72 72 72 Belgium 65 63 63 63 63 63 Austria 61 58 58 58 58 59 Denmark 68 68 68 68 9 56 Ireland 50 50 50 50 50 50 Portugal 79 79 56 24 3 48 Germany 64 48 42 36 36 45 France 67 64 31 31 31 45 Finland 60 58 33 33 33 43 Australia 42 42 42 42 42 42 Spain 69 65 25 25 13 39 New Zealand 38 38 38 38 38 38 Sweden 66 63 41 8 8 37 Iceland 57 54 54 8 8 36 United Kingdom 28 28 28 28 28 28 Netherlands 71 59 3 3 3 28 Switzerland 80 40 0 0 0 24 Luxembourg 87 8 8 8 8 24 Canada 52 14 14 14 14 22 Hungary 48 13 13 13 13 20 Poland 42 16 8 8 8 16 Czech Republic 33 11 11 11 11 15 Japan 45 3 3 3 3 11 Turkey 46 0 0 0 0 9 Slovak Republic 32 3 3 3 3 9 Greece 33 5 1 1 1 8 Italy 37 0 0 0 0 7 Korea 31 0 0 0 0 6 United States 28 0 0 0 0 6 Median 52 40 25 13 9 28

a) Countries are shown in descending order of the overall generosity measure (the five-year average). Calculations consider cash incomes (excluding, for instance, employer contributions to health or pension insurance for workers and in-kind transfers for the unemployed) as well as income taxes and mandatory social security contributions paid by employees. To focus on the role of unemployment benefits, they assume that no social assistance or housing-related benefits are available as income top-ups for low-income families (covered in Figure 1.19 below). Any entitlements to severance payments are also not accounted for. Net replacement rates are evaluated for a prime-age worker (aged 40) with a “long” and uninterrupted employment record. They are averages over 12-months, four different stylised family types (single and one-earner couple, with and without children) and two earnings levels (67% and 100% of average full-time wages). Due to benefit ceilings, net replacement rates are lower for individuals with above-average earnings. See OECD (2007a) for full details. Source: OECD tax-benefit models (www.oecd.org/els/social/workincentives).

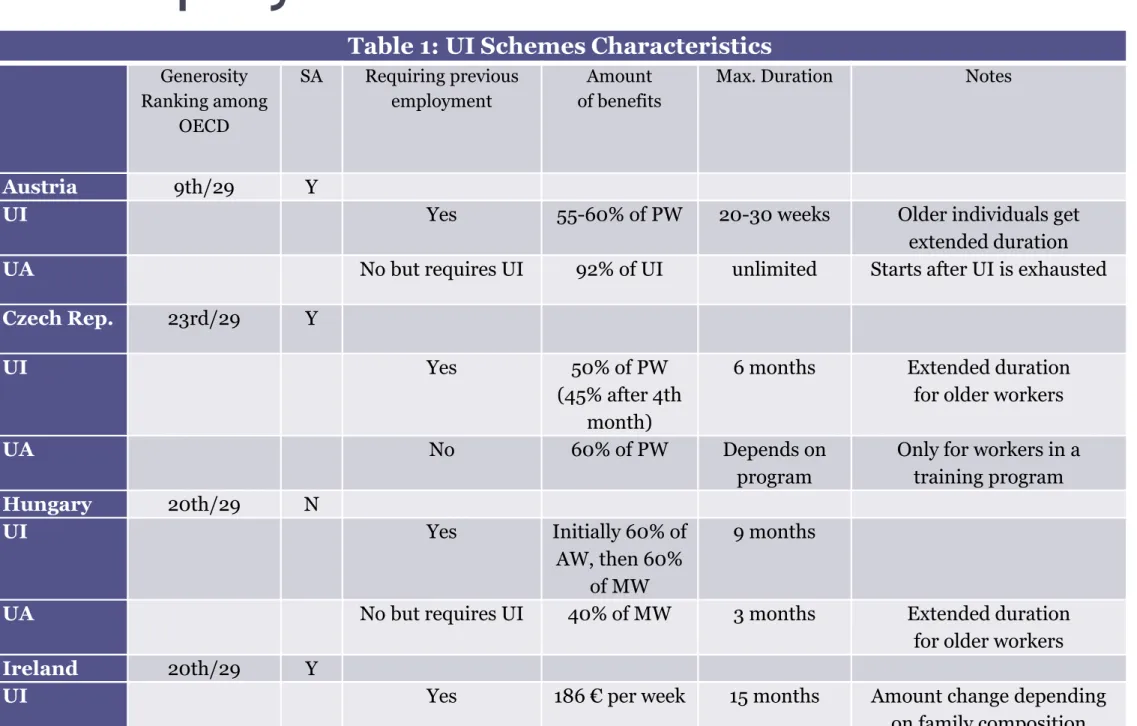

Unemployment benefits

Table 1: UI Schemes Characteristics

Generosity Ranking among OECD SA Requiring previous employment Amount of benefits

Max. Duration Notes

Austria 9th/29 Y

UI Yes 55-60% of PW 20-30 weeks Older individuals get extended duration

UA No but requires UI 92% of UI unlimited Starts after UI is exhausted

Czech Rep. 23rd/29 Y

UI Yes 50% of PW

(45% after 4th month)

6 months Extended duration for older workers

UA No 60% of PW Depends on

program

Only for workers in a training program Hungary 20th/29 N UI Yes Initially 60% of AW, then 60% of MW 9 months

UA No but requires UI 40% of MW 3 months Extended duration for older workers

Ireland 20th/29 Y

UI Yes 186 € per week 15 months Amount change depending on family composition

Unemployment benefits

Italy 27th/29 N

UI Yes 50% of PW

(40% during last month)

7 months Older individuals get extended duration Netherland 16th/29 Y UI Yes 75% of PW (70% after 3rd month) 6-38 months depending on past contributions

A lower insurance exist for those not meeting contributions required

Spain 11th/29 N

UI No, but require contributions 70% PW (60% after 6th month) 12-24 months depending on past contributions

Has lower and higher limit that depends on family

composition

UA No, but requires UI 80% of base income (IPREM)

6 months extendible up to

18

Base Income (IPREM) is set by government and was 500€

in 2007

Sweden 13th /29 Y S.A requires job search

UI Yes 80% of PW for

200 days and then 70%

300 days Voluntary

UA Yes 360 SEK 300 days It is not applied after UI is exhausted

UK 15th/29 N

UI Yes 59.15£ 6 months Lower amounts for workers below 25 years

UA No 59.15 less actual

income

unlimited Amounts change depending on family composition

Measuring Active Employment Services

and Search Requirements

• We evaluate several aspects:

1) Placemente efforts at initial registration

2) If and when an individual action plans is devised

3) Frequency of search of reports on search activity

4) Whether a proof of search is revised

5) Whether counseling is given also at later stages of unemployment spells.

• Point 1 and 2 makes up the "initial" activity of the system.

• Point 2,3,4 and 5 makes up the "continuing" effect of the system.

• We will give a scor of 0, 0.5 or 1 to each of this aspects to each system and obtain a score for the "initial", "continuing" and "overal" activity.

Table 2: Active Employment Services and Search Requirements Placement efforts at initial registration Individual Action Plan (IAP) Frequency of report on search activity Proof of search required Further interviews during unemployment Score: Initial/ Continuing/ Overall Austria EC checks for readiness of

work and may offer a vacancy. Workers’ application is compulsory

It is agreed at registration

Once a week No At least every 3

months, their actual frequency depends

on the IAP

2/2.5/3.5

Czech Rep. EC checks for readiness of work and may offer a

vacancy. Workers’ application is compulsory It is agreed within 6 months and is not compulsory Every 2 weeks No Every 2 weeks 1/2/3

France EC checks for readiness of work and may offer a

vacancy. Workers’ application is compulsory It is agreed within 1 week Every month but only after the 4th

Yes Every month but only after the 4th

2/4/5

Germany EC checks for readiness of work and may offer a

vacancy. Workers’ application is compulsory It is agreed within 10 days No reporting required No Usually every 2 months 2/1.5/2.5

Hungary EC checks for readiness of work but usually do not

offer a vacancy It is agreed shortly after registration Once a month. Often included in IAP

Every 3 months, but depends on the IAP

1/3/3

Ireland EC checks for readiness of work but usually do not

offer a vacancy It is agreed after three months Usually once a month No Every 3 months 0/2/2

Italy Though EC is not required to check for suitable vacancies, actual effort

varies according to EC It is agreed at registration No reporting required No None is compulsory,

but they may be included in the IAP.

1.5/1/1.5

Netherlands Law does not require EC to check for suitable

vacancies nor is application compulsory. No IAP is carried out Once a month

Yes At least once a

month, their actual frequency depends

on the IAP

0/3/3

Spain EC checks for readiness of work but usually do not

offer a vacancy

It is agreed at 6 or 12 months

Every 3 months

No Usually every two

months

0/1/1

Sweden EC checks for readiness of work but usually do not

offer a vacancy

It is agreed within 1 month

Every 6 weeks

Yes Every 4-8 weeks 0.5/2.5/2.5

UK EC checks for readiness of

work and may offer a vacancy. Workers’ application is compulsory It is agreed within 2 weeks Every 2 weeks