A

ud

it C

om

mit

te

e G

ov

erna

nc

e

2016–17:2

A

ug

ust

2

01

6

Victorian Auditor-General’s Report

August 2016

2016–17:2

V I C T O R I A

Victorian

Auditor-General

Audit Committee

Governance

Ordered to be published VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTERThis report is printed on Monza Recycled paper. Monza Recycled is certified Carbon Neutral by The Carbon Reduction Institute (CRI) in accordance with the global Greenhouse Gas Protocol and ISO 14040 framework. TheLifecycle Analysis (LCA) for Monza Recycled is cradle to grave including Scopes 1, 2 and 3. It has FSC Mix Certification combined with 55%

The Hon Bruce Atkinson MLC The Hon Telmo Languiller MP

President Speaker

Legislative Council Legislative Assembly

Parliament House Parliament House

Melbourne Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Audit Committee Governance.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

Contents

Auditor-General’s comments ... vii

Audit summary ... ix

Conclusions ... ix

Findings ...x

Recommendations ... xiii

Submissions and comments received ... xiv

1. Background ... 1

1.1 Introduction ... 1

1.2 Legislation and guidance ... 2

1.3 Audit committees in different governance structures ... 4

1.4 Machinery-of-government changes ... 5

1.5 Audit objective and scope ... 8

1.6 Audit method and cost ... 8

1.7 Structure of the report ... 8

2. Audit committee governance and operations ... 9

2.1 Introduction ... 10

2.2 Conclusion ... 10

2.3 Composition, capability and induction ... 11

2.4 Effective operational support for audit committees ... 17

2.5 Effective evaluation of audit committee performance... 22

3. Oversight of risk management ... 25

3.1 Introduction ... 26

3.2 Conclusion ... 26

3.3 Responsibility for risk management ... 26

3.4 Case studies on overseeing risk management ... 27

4. Oversight of internal audit ... 35

4.1 Introduction ... 36

5.4 Agency tracking and reporting ... 47 5.5 Audit committee oversight of audit actions ... 48

Appendix A. Key Standing Directions requirements for audit

committees ... 53

Auditor-General’s comments

Audit committees play a key role in the governance framework of government departments in Victoria. Their role is to provide departmental management with an independent and objective source of advice on matters including financialreporting, risk management, and internal and external audit.

My audit reviewed the governance arrangements for audit committees in all seven state government departments as well as Victoria Police. It also assessed the level of compliance with the Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance (Standing Directions) and the extent to which good practice is being applied across the audited agencies.

While the governance arrangements for audit committees are generally effective, there are several key areas where there is room for improvement. These include the need for agencies to:

• ensure that their audit committee maintains the required mix of skills • regularly and comprehensively assess the performance of committee

members and the effectiveness of their audit committee.

The Standing Directions were recently reviewed, and the changes make addressing these gaps even more important.

I am most concerned that the revised requirements reduce the obligations on audit committees by limiting the management actions they are required to monitor— under the 2016 Standing Directions, audit committees are only required to monitor actions that relate to or impact on ‘financial management, performance and sustainability’. The express requirement to review the impact of management

actions―ensuring that underlying issues have been effectively resolved―has also been removed.

These changes are a backward step that could lead to agencies failing to address the underlying issues and risks that have been identified by internal and external audits. Further, these changes underscore the importance of effective governance arrangements for audit committees. While these changes were made in response to concerns that the previous Standing Directions went beyond the bounds of the

Financial Management Act 1994, they have resulted in Victoria’s legislative framework now being inconsistent with best practice for audit committees— including the Department of Treasury & Finance’s own guidance which

recommends that committees monitor all recommendations. It also puts Victoria behind New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory where this is a

Audit team

Andrew Evans Engagement Leader Verena Juebner Team Leader Stefania Colla Analystdepartments and Victoria Police who participated in this audit.

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

Audit summary

Audit summary

Audit committees play a key accountability role in the governance framework of Victorian public sector agencies. While management retains ultimate accountability for operations, audit committees independently review and assess the

effectiveness of key aspects of an agency’s operations.

The Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance (Standing Directions) set out the core requirements, responsibilities and functions of audit committees. The Standing Directions were recently reviewed by the Department of Treasury & Finance (DTF), and the revised 2016 Standing Directions came into effect on 1 July 2016, replacing the 2003 Standing Directions. Key requirements of the Standing Directions expect audit committees to:

• have a charter that outlines the committee’s roles and responsibilities • be independent and have the appropriate skills to discharge committee

responsibilities

• oversee risk management, the internal audit function and the implementation of management actions in response to internal and external audit

recommendations

• undertake annual self-assessments and review committee membership at least once every three years.

This audit examined the effectiveness of governance arrangements for audit committees, including their composition, operational arrangements and the information they receive. It included the seven portfolio departments and Victoria Police.

For Part 2 of this report, we assessed the governance and operations of all eight audit committees. For Parts 3, 4 and 5, we selected a sample of agencies with varying processes and procedures. We have de-identified the agencies for these Parts to focus on the lessons that can be applied to all audit committees.

Conclusions

The governance arrangements for audit committees are generally effective, although there is room for improvement in some areas. The recent changes to the Standing Directions heighten the need for agencies to make sure audit committees have the appropriate membership, independence and capability, and are

performing their functions effectively. These functions include overseeing risk management and internal audit, and ensuring that management actions taken in

providers have no conflict of interest.

Some agencies are considering reducing the role that audit committees have in monitoring management actions in response to internal and external audit recommendations, in line with the revised Standing Directions. However, these changes are concerning—they decrease the level of accountability for

management and, importantly, could lead to agencies failing to effectively address the underlying issues and risks that have been identified by audits. Audit

committees should continue to monitor all management actions in response to internal and external audit recommendations, and implement a risk-based process to assess whether completed management actions have adequately addressed the underlying risks or issues.

Findings

Audit committee governance and operations

Composition, capability and induction

The eight audit committees we assessed largely meet the requirements for membership, independence and capability under the 2003 Standing Directions. Only one audit committee is not currently compliant with the new Standing Directions requirement to have an equal number or majority of independent members, but it is working towards an equal membership.

Currently only three agencies have robust processes for determining the skills required for their audit committee members, or for identifying and addressing any material gaps. The quality and comprehensiveness of induction processes for new members varies across agencies. In light of the reduced prescriptiveness of the 2016 Standing Directions regarding skills and induction requirements, improving these aspects will be even more important.

Effective operational support for audit committees

While audit committees’ access to information and agency staff is generally appropriate, the biggest concern for committee members is the volume of the papers received and the time available to review that information prior to meetings. As a priority, audit committees must work with management to address the volume,

Audit summary

Effective evaluation of audit committee performance

Agencies must become more rigorous in periodically assessing whether their audit committees are meeting their functions. All audit committees have undertaken or intend to undertake the mandatory annual self-assessments. However, the 2016 Standing Directions now require that agencies formally review the audit

committee’s performance and membership at least once every three years. Of the eight agencies we assessed, two agencies have commissioned performance reviews and two plan to do so. Agencies are also required to review the performance of individual committee members in line with the new Standing Directions requirements.

Overseeing risk management

Audit committees must maintain oversight of agency-wide risk, despite the narrowing of the focus of the 2016 Standing Directions. This is because the 2016 Standing Directions continue to mandate the application of the Victorian

Government Risk Management Framework, and audit committees must verify the agency’s compliance with these requirements. Two out of the three audit

committees examined in Part 3 have been fulfilling the requirements under the Standing Directions and their charters to oversee risk management. These committees have been supported by consistent risk reporting, and there is evidence that the audit committees have improved agency risk management. For one of these agencies, we observed good discussion on risk at the committee meeting that we attended, but we found limited evidence of discussion in the audit committee minutes. While the agency advised that minutes are intended to mainly capture actions, agencies should consider the benefits of detailing elements of the discussion and noting where members have questioned and/or provided advice to management. This would provide assurance to the head of the agency that the committee is sufficiently testing the material that comes before it and would assist with assessing the performance of committee members.

The third audit committee’s oversight of risk has been hampered by inconsistent risk management practices across the agency and unclear responsibilities. The agency is working to address this.

Overseeing internal audit

The internal audit function is an important source of information and assurance for the audit committee on an agency’s performance and risk management activities. Under the Standing Directions, the audit committee has a key role in directing and reviewing the work of the agency’s internal audit function.

One audit committee is establishing a new process for approving the detailed internal audit scopes and another is ensuring it reviews and approves all consulting work its outsourced internal audit firm conducts to ensure the firm is not conflicted. The third audit committee has effective procedures for approval of internal audit scopes and has in place a process to review non-audit activities.

Monitoring implementation and impact of audit actions

Changes to the Standing Directions

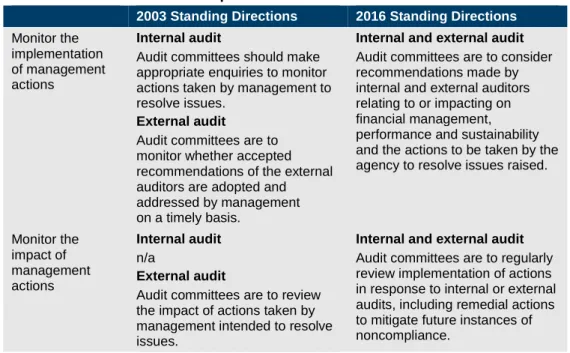

The revised 2016 Standing Directions limit the responsibility of audit committees to monitoring the implementation of only those audit recommendations that ‘relate to or impact on financial management, performance and sustainability’. The previous 2003 requirement was for audit committees to monitor all audit recommendations, whether they be related to finance, health, safety or any other area.

DTF advised that these limitations were made so that the Standing Directions do not extend beyond the Minister for Finance’s powers under the Financial

Management Act 1994. However, these changes are a backward step that

decrease the level of accountability for and governance of management actions that fall outside this definitionand could lead to agencies failing to address important issues. While guidance accompanying the 2016 Standing Directions notes the expectation that audit committees continue to monitor all

recommendations, audit committees may choose to be selective.

The 2016 Standing Directions also reduce the requirement for audit committees to review whether management actions resolve the underlying issues identified by audits. Nevertheless, DTF advised that it expects audit committees to take a risk-based approach to this function.

Compliance with Standing Directions requirements

In line with the 2003 Standing Directions, all audit committees have been monitoring the implementation of management actions in response to all internal and external audit recommendations. Members consistently highlighted that their role in monitoring these actions—particularly the high number of outstanding and overdue actions—is one of their greatest challenges and takes up a significant amount of their time. As a result, they are working to reduce the number of

Audit summary

This audit committee’s 2016 follow-up review found that management actions are inconsistently implemented across divisions and business units and that there is no clear consideration of the original audit finding or of risk mitigation. This reinforces the value of such follow-up reviews and indicates that agencies still have work to do to improve the effective implementation of audit actions across the organisation. Some agencies are considering reducing the role that audit committees have in monitoring management actions. While this is in line with the revised Standing Directions, these changes are concerning. They decrease the level of

accountability and, importantly, could lead to agencies failing to effectively address the underlying issues and risks identified by audits. Audit committees need to establish effective processes for implementing all management actions, and a risk-based approach for assessing whether completed management actions have effectively addressed the underlying risks or issues.

Recommendations

Number Recommendation Page

That agencies:

1. develop and maintain mechanisms to identify the appropriate mix of skills and experience needed for audit committee membership and to identify any gaps

23

2. ensure that annual work programs cover each audit committee charter responsibility

23

3. work with the audit committee to better define, or refine, the committee’s information needs, including whether reported information is reliable and understandable

23

4. align audit committee meeting materials and agendas with priority areas

23

5. conduct formal reviews of the performance and

independence of independent audit committee members before reappointing them for additional terms

23

6. consider offering continuing education that addresses topics relevant to the audit committee’s needs

23

7. work with the audit committee to evaluate whether it has the capacity to fully acquit its obligations under the

Standing Directions and charter, or whether there is a need to review its role, structure and/or operational

arrangements

23

8. ensure that the risk oversight responsibilities of the audit committee are clear and that its role is supported by consistent risk reporting

33

9. consider whether audit committee minutes should include relevant elements of the committee’s discussion to transparently demonstrate the committee’s performance

committee makes the final decision on potential conflicts of interest for outsourced internal audit providers who perform other consultancy work for the agency

12. ensure that the audit committee has a formal process to review the performance of the internal audit function and report the results to the head of the agency

42

13. ensure that the audit committee continues to monitor all audit actions, even if they fall outside the scope of financial management, performance and sustainability

52

14. have the audit committee require internal auditors to conduct periodic testing of whether audit actions reported as completed by management have been effectively implemented

52

15. have the audit committee require the internal audit function to undertake periodic assessments of a sample of closed audit actions to ensure that underlying issues have been effectively resolved—these should be selected in a risk-based manner.

52

Submissions and comments received

Throughout the course of the audit we have professionally engaged with: • the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources • the Department of Education & Training• the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning • the Department of Health & Human Services

• the Department of Justice & Regulation • the Department of Premier & Cabinet • the Department of Treasury & Finance • Victoria Police.

In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report to those agencies and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix B.

1

Background

1.1

Introduction

1.1.1

The importance of good public sector governance

Good governance is integral to the Victorian public sector effectively managing its operations, conforming to applicable legislative and policy requirements, and being accountable for the expenditure of public funds and the achievement of outcomes. Good governance also assists in meeting public expectations of transparency and integrity and enhances confidence in decisions and actions.

There are a number of elements that underpin good governance, such as having strong leadership and effective systems and processes. Victorian public sector agencies1 also typically have a number of committees covering areas such as audit and risk,

procurement, human resources, and performance and evaluation, among others.

1.1.2

The role and composition of audit committees

Audit committees play a key accountability role in the governance framework of Victorian public sector agencies. While management retains ultimate accountability for operations, audit committees enhance governance practices by independently

reviewing and assessing the effectiveness of key aspects of an agency’s operations. These aspects include:

• risk management―systems and processes that facilitate the identification, assessment, evaluation and treatment of risk

• financial statements―form part of the financial reporting process; a full statement normally includes, among other things, a balance sheet, an income statement, a statement of cash flows and a statement of changes in equity

• internal controls―including legislative and policy compliance, business continuity management, delegations and ethical and lawful conduct

• compliance requirements―laws, policies and regulations agencies must comply with

• internal audit―reviews on the performance of an agency and its control environment

• implementation of management actions in response to internal and external audit recommendations―actions taken to address recommendations arising from internal and external audits are followed up and addressed.

The effectiveness of an audit committee is significantly impacted by its member composition, its roles and responsibilities, and its operating arrangements, including the quality and timeliness of information it receives from management and its lines of communication and reporting. To be fully effective, an audit committee must be sufficiently independent from management and free from any undue influence. Audit committees therefore typically have an independent chair and have either a majority or equal number of independent members. They also exclude from membership certain agency employees who would represent a conflict of interest, such as the head of the agency, the chief financial officer and internal auditors. However, audit committees usually do have members from within the agency in addition to independent members, with around six to eight members in total. All members are required to exercise independent judgement and be objective in their deliberations, decisions and advice.

1.1.3

Support for audit committees

Under the Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance (Standing Directions), discussed in detail in Section 1.2.1, agencies are required to:

• establish an audit committee and appoint members

• approve the audit committee charter, which outlines the committee’s roles and responsibilities

• enable the committee to have access to the head of the agency, the chief financial officer, and internal and external auditors, when required

• review committee membership at least once every three years.

Audit committees are also supported by secretariat functions, which are usually fulfilled by agency staff. The secretariat is responsible for arranging committee meetings, collating and distributing meeting papers, attending meetings and drafting meeting minutes.

All audit committees are currently in the process of updating their charters because of the changes to the Standing Directions, discussed in the following Section.

1.2

Legislation and guidance

1.2.1

Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance

The Standing Directions under the Financial Management Act1994 set out the core requirements, responsibilities and functions of audit committees. The Standing Directions were recently reviewed by the Department of Treasury & Finance (DTF), and the revised 2016 Standing Directions came into effect on 1 July 2016, replacing the 2003 Standing Directions. The review aimed, in part, to:

Background

Key requirements that are common to both versions of the Standing Directions expect audit committees to:

• have a charter

• be independent, with an independent member as chair

• exclude from membership the head of the agency and the chief financial officer

• have the appropriate skills to discharge committee responsibilities

• undertake annual self-assessments.

The 2016 Standing Directions reduce the requirements of audit committees in some areas, such as by limiting the management actions that audit committees are required to monitor to those that relate to or impact on ‘financial management, performance and sustainability’. Appendix A compares the 2003 and 2016 Standing Directions

requirements relevant to audit committees.

1.2.2

Guidance

Both versions of the Standing Directions are accompanied by guidance material developed by DTF to support agencies to implement the Standing Directions. For example, despite the change to the Standing Directions discussed above, the guidance expects that audit committees continue to monitor all audit actions. Other relevant better practice guidance includes the Australian National Audit Office’s Public Sector Audit Committees: Independent assurance and advice for Accountable

Authorities (March 2015).

1.2.3

Reporting compliance with the Standing Directions

The role of public sector agencies

Under both versions of the Standing Directions, public sector agencies are required to annually certify their compliance with all applicable Standing Directions. However, the 2016 regime requires more rigour, transparency and accountability:

• Under the 2003 Standing Directions, agencies made an annual certification of compliance that was internal to government. The only public attestation was for risk management and insurance compliance.

• The 2016 Standing Directions require a public attestation in annual reports against all applicable requirements as well as the disclosure of all material noncompliance.

Audit committees are required to review the accuracy of the agency’s compliance reporting under both versions of the Standing Directions.

The role of the Department of Treasury & Finance

DTF is responsible for reporting whole-of-government compliance levels with the Standing Directions to the Minister for Finance.

VAGO’s May 2012 audit Personal Expense Reimbursement, Travel Expenses and Corporate Credit Cards found that DTF had not adequately scrutinised the accuracy of agencies’ reports and did not detect agencies’ reporting failures. The report noted that DTF must apply greater scrutiny to agencies’ submissions under the 2003 Standing Directions.

Under the 2016 Standing Directions, DTF is not required to test the accuracy of compliance reporting, although it is able to conduct assurance programs ‘as part of monitoring the effectiveness of the whole of state financial management framework’. DTF advises that it intends to conduct future assurance programs for this purpose.

1.3

Audit committees in different governance

structures

How an audit committee is constituted, to whom it provides advice and what

information is available to independent audit committee members depends on whether the responsible body has a statutory board or not.

The agencies included in this audit—the seven portfolio departments and Victoria Police—do not have statutory boards. Therefore, the head of the agency (the secretary or chief commissioner) retains ultimate accountability for agency operations. It is also the head of the agency who appoints audit committee members. The audit committee’s role is to provide independent advice on key aspects of operations to the head of the agency.

This differs considerably from private sector entities and from public sector entities that have a statutory board. In those organisations, board members are generally

appointed by a third party―the relevant minister, in the case of public sector entities, and shareholders, in the case of private sector organisations. The role and duties of the board include setting the agency’s strategic direction, establishing and reviewing policies, monitoring and reviewing the effectiveness of risk management and ensuring that the entity operates within legislation. The audit committee is a subcommittee of the board and, accordingly, the role of the audit committee is usually to review and make recommendations to the board, which has the power to action these

recommendations. As head of the organisation, the chief executive officer is

responsible for the day-to-day management of the public entity in accordance with the law, government policies, and the decisions of the board.

Background

Independent members that we interviewed as part of this audit, who are also members of audit committees in organisations where there is a board, informed us that being a member of the board generally gave them more oversight of entity operations. On the other hand, independent members of audit committees of agencies with no

board―such as in the eight audited agencies―do not have the same level of exposure to the internal workings of the agency. Therefore, there is greater reliance on internal briefings and other information provided to the audit committee.

1.4

Machinery-of-government changes

Machinery-of-government changes are the transfer of functions between departments. They are used by governments to align responsibilities in a way that they believe will assist in delivering policy priorities.

Machinery-of-government changes are one of the key factors that can impact the effectiveness of audit committees. This is because these changes can result in:

• agency staff turnover which can, in turn, result in the loss of corporate knowledge

• the addition of new portfolio responsibilities and therefore new portfolio risks which management must identify and mitigate, including through the coverage of internal audits

• additional outstanding audit actions inherited from previous iterations of the department which management must monitor and action

• the need for the committee to adapt to and oversee new agency functions. Apart from Victoria Police, all of the agencies included in this audit were affected by the most recent machinery-of-government changes, shown in Figure 1A. These changes saw nine departments merged into seven and the reallocation of functions between departments.

Figure 1A

Victorian public service machinery-of-government changes effective 1 January 2015

Background

1.4.1

Distribution of audit committee members before and

after machinery-of-government changes

Figure 1B shows the movement of audit committee members from pre-machinery-of-government audit committees to the audit committees for the newly developed agencies shown in Figure 1A. We only looked at the Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS), DEDJTR and DELWP, as these were most significantly affected by the changes. Figure 1B shows that, in forming the new audit committees, departments:

• included a fairly equal representation of members from previous audit committees

• generally appointed members with a good mix of experience in the sectors the new agencies would be responsible for overseeing.

Figure 1B

Distribution of audit committee members before and after machinery-of-government changes

• health

• ambulance services

• families and children

• housing, disability and ageing

• mental health

• sport (except for major sporting events) • youth affairs • public transport • agriculture • creative industries • employment

• energy and resources

• industry

• ports

• regional development

• roads and road safety

• small business, innovation and trade

• tourism and major events (including major sporting events)

• environment, climate change and water

• local government

• planning

Department of Health & Human Services

Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources

Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning Department of Health

Department of Transport, Planning & Local Infrastructure

(sport excluding major events)

Department of Human Services

(excluding families and children, and women)

Department of Premier & Cabinet

(arts only)

Department of Environment & Primary Industries

(agriculture, energy and resources only)

Department of Transport, Planning & Local Infrastructure

(excluding local government, planning, roads and sport (excluding major events))

Department of State Development, Business & Innovation

Department of Transport, Planning & Local Infrastructure

(local government and planning only)

Department of Environment & Primary Industries

(excluding agriculture, energy

1.5

Audit objective and scope

The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of governance arrangements for audit committees, including their composition, operational

arrangements and the information they received. The audit focused on eight agencies:

• the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources

• the Department of Education & Training

• the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning

• the Department of Health & Human Services

• the Department of Justice & Regulation

• the Department of Premier & Cabinet

• the Department of Treasury & Finance

• Victoria Police.

This audit assessed all eight agencies for Part 2 of the report. A sample of agencies with varying processes and procedures was selected for Parts 3, 4 and 5. We have de-identified the agencies for these Parts to focus on the lessons that can be applied to all audit committees.

1.6

Audit method and cost

The audit examined audit committee governance through document reviews and interviews with audit committee members and agency staff. We also attended and observed audit committee meetings.

The audit was carried out under sector 15 of the Audit Act 1994, in keeping with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

Total cost of the audit was $410 000.

1.7

Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

• Part 2 examines principles that help audit committees to add value

• Part 3 examines committee oversight of risk management

• Part 4 examines committee oversight of internal audit

• Part 5 examines committee monitoring of actions taken in response to audit recommendations

• Appendix A compares the 2003 and 2016 Standing Directions requirements for audit committees.

2

Audit committee governance

and operations

At a glance

Background

To maximise the effectiveness of the audit committee, it must have appropriate membership, access to information and operational support, and be subject to regular performance reviews.

Conclusion

Overall, audit committees largely meet the requirements for membership,

independence and capability under the Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance (Standing Directions). However, agencies need to better assure themselves that audit committees have the appropriate skills and capabilities to discharge their

responsibilities. In light of the reduced prescriptiveness of the 2016 Standing

Directions, it is even more important that agencies have a mechanism to determine the right mix of skills and capabilities for the audit committee.

While audit committees had appropriate access to information and agency staff, agencies should work with audit committees to decrease the volume of information provided to them, seek ways to improve the readability of papers and/or increase the amount of time available to review them.

Agencies need to be more rigorous in periodically assessing whether audit committees are meeting their functions. Agencies need to appropriately review the performance of individual committee members in accordance with the performance criteria in their contracts.

Recommendations

That agencies ensure that the audit committee has the appropriate mix of skills, receives quality and timely information, addresses all its charter responsibilities, has well-planned meetings and effectively acquits its responsibilities throughout the year.

2.1

Introduction

For audit committees to be effective, it is important that:

• members are independent of management andact objectively and impartially

• members have an appropriate mix of skills and experience relevant to the agency’s activities and to the responsibilities of the committee

• new members receive an appropriate induction and that all members are kept abreast of developments within the agency and sector

• the committee is appropriately supported by effective operational arrangements, such as having well-planned meetings and access to good-quality information. Audit committees and agencies alike must also take steps to periodically review the performance of the committee and its members to ensure the committee is meeting its roles and responsibilities effectively.

2.2

Conclusion

Overall, audit committees largely meet the requirements for membership,

independence and capability under both the 2003 and 2016 Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance (Standing Directions). Of the eight audited agencies, seven currently comply with the new Standing Directions requirement to have equal or majority independent members, and the eighth agency is working to address this. Currently, only three agencies have robust processes for identifying material skills gaps, and the quality and comprehensiveness of induction and training for members varied across audit committees. The reduced prescriptiveness of the 2016 Standing Directions means that addressing these issues will be even more important.

While the audit committees have appropriate access to agency information and staff, committee members’ biggest concern is the volume of papers they receive and the time available in which to review them. Where this is a problem, agency management should decrease the volume of information, seek ways to improve the readability of papers and/or increase the amount of time available for committee members to review them. Further, not all agencies had an annual work program that clearly showed how all charter responsibilities would be addressed throughout the year.

Agencies need to become more rigorous in periodically assessing whether their audit committee is meeting its function. While machinery-of-government changes have had an impact in this regard, only three agencies have reviewed their audit committees’ performance in the past three years. The 2016 Standing Directions require that this occurs every three years. Agencies also need to appropriately review the performance of individual committee members in accordance with the performance criteria in their contracts.

Audit committee governance and operations

2.3

Composition, capability and induction

2.3.1

Appropriate independence and capability

The number of members on an audit committee, and the skills and experience they require, depends on the complexity, nature and scale of the agency’s responsibilities, activities and systems. Agencies need to balance the need for audit committees to be sufficiently independent and provide a strategic perspective while maintaining up-to-date agency and sector knowledge.

Figure 2A summarises the key Standing Directions requirements and better practice guidance for composition and capability and our assessment of compliance across the eight audited agencies.

Figure 2A

Audit committee composition and capability

Category Source Compliance

At least two independent members 2003 Standing Directions 8/8 Majority independent members 2016 Standing Directions 6/8 Equal independent and agency

members 2016 Standing Directions guidance 1/8 Agency completes skills matrix Australian National Audit Office

(ANAO) better practice(a) 3/8

Where a skills matrix is not

completed, is the skills mix assessed:

• as part of agency reviews? ANAO better practice 2/5(b)

• as part of committee

self-assessments? ANAO better practice 5/5

(b)

Regional representation on audit

committee ANAO better practice 2/6

(c)

(a) ANAO, Public Sector Audit Committees: Independent assurance and advice for Accountable Authorities, March 2015.

(b) Five agencies do not complete skills matrices.

(c) The Department of Treasury & Finance and the Department of Premier & Cabinet are not required to have regional representation.

Number of independent members

Audit committees provide an independent source of assurance and advice to entities on key aspects of the entity’s operations. They need to be independent of

management and act objectively and impartially, and should be free from conflicts of interest, inherent bias or undue external influence.

The Department of Justice & Regulation (DJR) had equal independent and agency members on its committee as at 1 July 2016, when the 2016 Standing Directions came into effect. This complies with the new requirements, as the accompanying guidance notes that committees with equal membership are permitted where the chair has the casting vote on decisions. However, DJR has recently approved the appointment of an additional independent member.

Victoria Police has, until recently, had two independent members and six agency members—it was the only audit committee where independent members were in the minority for several years. While it met the 2003 Standing Directions requirements of having two independent members, the agency will not comply with the 2016 Standing Directions until later in 2016, although it has significantly progressed towards this. At 1 July 2016, it had reduced the number of agency members to four and appointed a third independent member. It is currently in the process of appointing a fourth independent member.

The Department of Premier & Cabinet’s (DPC) audit committee is composed of only independent members. This is discussed in Figure 2B.

Figure 2B

Case Study: Independent members only on the audit committee Since 2015, DPC’s audit committee has been made up solely of independent members, with attendance by management through a standing invitation or as required by the committee. The department notes a number of advantages of this structure, including:

• avoidance of perceived or actual conflicts or undue influence by agency members, which allows for more open discussion

• more efficient use of senior executives’ time—rather than attending entire meetings, they are only required to attend relevant sections.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Regional representation

Several agencies that have significant operations in regional areas have recognised the benefits of having a regional representative on their audit committee. This is discussed in Figure 2C.

Audit committee governance and operations

Figure 2C

Case Study: Regional representation on the audit committee DJR and the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning (DELWP) both include an agency member from one of their regions in their audit committee, who provides an operational perspective and assists with the identification of service delivery risks. Regional representation also helps to communicate what the audit committee is focusing on back to the regions.

DELWP periodically rotates members from each of its regions onto its audit committee and holds some audit committee meetings in regional locations to enable staff based in regional locations to attend.

The Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) also has an agency member on its committee who was until recently the deputy secretary for one of the regions. The member’s role within the department has now changed, and DHHS has advised that it will review regional representation on the committee.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Appropriate skills and experience

While the 2016 Standing Directions are less prescriptive than the 2003 Standing Directions in terms of the specific skills and experience an audit committee member requires, the committee must be constituted by members with ‘appropriate skills and experience to discharge their responsibilities’, who have an understanding of the business environment in which the agency operates. At least one member must also have appropriate expertise in financial accounting or auditing.

Agencies must assure themselves that the audit committee, as a collective, maintains the required mix of skills. To do this, better-practice agencies develop and maintain skills matrices, described in Figure 2D.

Figure 2D Skills matrices

Agencies should develop and maintain a skills matrix that identifies the skills that the audit committee needs and how those needs are currently being met. Ideally, the matrix will identify gaps in the committee’s capability that must be filled. It is also a good way to assure the head of the agency that the appropriate skills are in place.

Matrices might specify:

• specific qualifications

• experience in risk management

• experience in information technology

• understanding of the portfolio that the agency is responsible for

• a corporate governance or legal background.

In order to develop a skills matrix, agencies should identify the desired skills mix and each member should undertake a high-level assessment of their contribution to each skill. To preserve an appropriate level of experience on the committee, particularly given the need for audit committees to periodically rotate their members, skills matrices might also include the aggregate number of years members have been on the audit committee.

As shown in Figure 2A, only three of the eight audit committees we assessed have skills matrices in place, but two agencies advised that they are developing them for their committees. A better-practice example is DELWP’s audit committee which

completes a skills matrix annually and includes it in the audit committee’s annual report to the secretary. DELWP’s 2014–15 matrix identified the need for some members to access training on how to understand financial statements, and DELWP intends to provide this.

While the other audit committees do not maintain and regularly update a skills matrix they do assess the mix of skills of their audit committees in several ways:

• Recruitment exercises―assessing the current mix of skills on the committee is common when recruiting new members and specifying the skill requirements and selection criteria for a new member.

• Performance reviews of the committee―an internal audit review of the Department of Education & Training’s (DET) audit committee surveyed members and key stakeholders on the skills and experience of the committee and gave members the opportunity to suggest additional skills and experience for future appointments to the committee.

• Committee self-assessments―self-assessments allow members to comment on the committee’s skills and experience. This type of self-assessment enabled Victoria Police’s audit committee to identify the need to improve members’ skills mix by focusing on information technology and risk management experience when appointing future independent members.

Reviewing member appointments

In reviewing membership, agencies should consider the guidance accompanying the 2016 Standing Directions. This states that audit committee members should be appointed for an initial term of up to three years and for no more than three terms of three years—a nine-year maximum term. The ANAO better practice guide suggests that agencies should assess a member’s performance when his or her tenure is being considered for extension. This assessment should include whether the member has:

• a good understanding of the agency’s business

• displayed the ability to act objectively and independently

• adequately prepared for committee meetings

Audit committee governance and operations

Figure 2E discusses some observations about appointment duration.

Figure 2E

Appointment durations

The two independent members of Victoria Police’s audit committee have served on the committee continuously since 2002 and early 2007 respectively. Neither have been subject to reviews of their performance or independence at any stage. Victoria Police informed us that it intends to appoint new members for three-year terms and that current members will be removed in a staggered manner to enable orderly succession and effective handover of corporate knowledge.

Another independent member we interviewed is on the audit committees at the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR) and DHHS and has served on several government department audit committees since 2001, including on the predecessor departments for DEDJTR and DHHS. While there was an initial assessment of the member’s skills and experience, there is no evidence of the member’s performance being specifically assessed against the criteria in the contract prior to the member’s reappointment. DEDJTR considered the member’s broad experience an asset that would ensure an effective transition to the new committee. Due to concerns that the significant length of service could impact on the member's ability to be independent, DEDJTR limited the member’s appointment to six months. DEDJTR has developed a revised audit committee charter, supported by an operations manual, that establishes a new process— members may only be reappointed after a formal review of their performance. The charter and operations manual are not yet approved.

While it is important to maintain corporate knowledge, agencies should monitor and consider members’ aggregate years of experience on the committee, including previous audit committees, before reappointing them. This is in line with ANAO better practice guidance, which notes the importance of balancing stability of membership against introducing new knowledge and experience.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

While agencies brief the head of the agency on the rationale for reappointing

members, they do not undertake assessments as outlined in the ANAO better practice guidance above. Figure 2F highlights a DJR practice that is a step in the right direction, although it could be further improved.

Figure 2F

Case study: Deciding whether to extend members’ terms In a 2016 briefing, DJR proposed extending the contracts of two independent members, noting both met all required criteria and key performance indicators (KPI). However, they only assessed the members’ performance against three of the four KPIs in their

contracts―attendance at meetings, timely responses to out-of-session requests, and meeting the Code of Conduct for Victorian Public Sector Employees.

While this is good, DJR did not assess the members against the fourth KPI, which is arguably the most crucial aspect of an independent member’s performance―participation

in discussions and providing meaningful independent contributions and input regarding audit committee matters. The measures that DJR identified for this KPI were:

• demonstrated application of skills and experience in discussions and decision-making

• demonstrated pre-meeting preparation

• evidence of participation and contributions in meeting minutes

• member responses in the annual performance self-assessment survey do not identify poor performance by the independent member.

DJR advised that this fourth KPI was not formally assessed as part of the process, because no performance issues had been identified with members at any stage during their term on the committee.

DJR also advised that any assessment of ‘participation and meaningful independent contribution’ would be highly subjective and difficult to substantiate with sufficient and appropriate evidence.

Agencies should develop ways to record and assess important aspects of a member’s preparation for and contribution to meetings, to enable the agency to make informed decisions about reappointing members.

As noted in Part 3, DJR (and other audit committees) should consider recording where members have questioned and probed and/or provided advice to management in the meeting minutes, which will also assist in building a record of a member’s performance. Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

2.3.2

Induction and training of new committee members

Specific induction and training requirements that were in the 2003 Standing Directions have been removed from the 2016 version. Better practice is to have a formal

induction process that is tailored to new members’ prior knowledge and experience and provides them with the additional knowledge required to properly understand and discharge their responsibilities.

While selection processes for new members clearly aim to confirm that prospective committee members have the expected level of competence, skills and experience prior to appointment, induction processes are still required to introduce new members to specific aspects of the agency or audit committee’s role. For example:

• independent audit committee members may require an introduction to the agency, its operating environment, and its specific risks and controls

• agency audit committee members may require training on the functions of the committee, such as how to adequately oversee risk management and internal

Audit committee governance and operations

Figure 2G discusses some of the training and induction practices at the audited agencies.

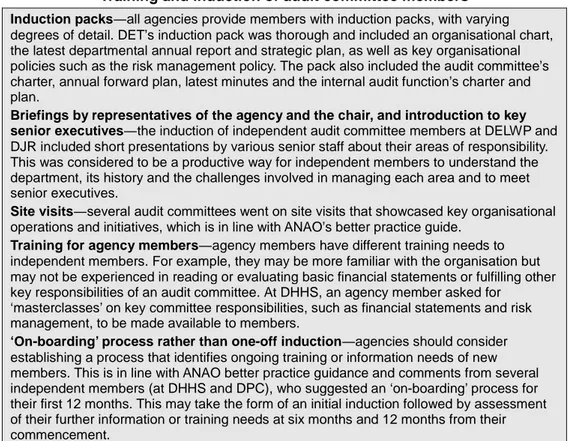

Figure 2G

Training and induction of audit committee members Induction packs―all agencies provide members with induction packs, with varying degrees of detail. DET’s induction pack was thorough and included an organisational chart, the latest departmental annual report and strategic plan, as well as key organisational policies such as the risk management policy. The pack also included the audit committee’s charter, annual forward plan, latest minutes and the internal audit function’s charter and plan.

Briefings by representatives of the agency and the chair, and introduction to key senior executives―the induction of independent audit committee members at DELWP and DJR included short presentations by various senior staff about their areas of responsibility. This was considered to be a productive way for independent members to understand the department, its history and the challenges involved in managing each area and to meet senior executives.

Site visits―several audit committees went on site visits that showcased key organisational operations and initiatives, which is in line with ANAO’s better practice guide.

Training for agency members―agency members have different training needs to independent members. For example, they may be more familiar with the organisation but may not be experienced in reading or evaluating basic financial statements or fulfilling other key responsibilities of an audit committee. At DHHS, an agency member asked for

‘masterclasses’ on key committee responsibilities, such as financial statements and risk management, to be made available to members.

‘On-boarding’ process rather than one-off induction―agencies should consider establishing a process that identifies ongoing training or information needs of new members. This is in line with ANAO better practice guidance and comments from several independent members (at DHHS and DPC), who suggested an ‘on-boarding’ process for their first 12 months. This may take the form of an initial induction followed by assessment of their further information or training needs at six months and 12 months from their commencement.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

2.4

Effective operational support for audit

committees

The operation of an audit committee is enhanced by having information that is high quality, meeting papers that are timely, complete and accurate, and meetings that are well planned and conducted efficiently. Further, audit committees and agencies alike must make certain that all of the committee’s responsibilities are discharged

2.4.1

Getting the right information

Meeting papers—managing information overload and providing

sufficient time for review

To fully appreciate the relevant issues, audit committees rely heavily on the information provided by management. This is particularly so in agencies where there is no board, as the independent members of the audit committee do not have the same level of exposure to the agency’s internal workings as board members would.

Audit committee self-assessments showed that members considered the volume and timing of papers a problem in most of the audited agencies. Two of the key concerns were that papers were not provided sufficiently in advance of meetings and that committee members were struggling with ‘information overload’. These themes were also reflected in our discussions with audit committee members:

• There is not enough time to get through everything, especially after the machinery-of-government changes.

• Papers are voluminous and could be more concise.

• More guidance around what is important to read would be good for agency members, as they do not need to read some of the background elements because they already know the information.

• The volume of papers is a big issue and they usually come out three to four days prior to the meeting.

• Papers are not produced specifically for the audit committee, and there is not enough time to read them in detail.

• The committee does not discuss who targets what area, but this happens naturally based on specific skills.

• Papers are consistently late due to excessive layers of management oversight. Agencies need to strike a balance between providing committee members with enough information and not overwhelming them with too much. Several committee members made suggestions for improvement, including:

• ensuring reports have concise executive summaries, where the key issues within the material are drawn out more to support discussion and consideration of relevant items

• including materiality levels on the papers indicating their importance

• presenting relevant information in a ‘dashboard’ style

Audit committee governance and operations

The ANAO better practice guidance notes that it is up to the chair to work closely with the secretariat and other management to ensure that papers are of an appropriate quality and length and are available far enough in advance of meetings to allow members to review and critique them. This is echoed by the Centro decision1, where the Federal Court of Australia questioned whether directors are required to apply their own minds to, and carry out a careful review of, statements and reports purporting to give a true and fair view of the position and performance of an entity they represent. Although the context of this case related to financial reporting in the private sector, its findings are relevant to and could be applied in principle to public sector audit committees. The Centro decision found that:

• information overload is not an excuse for failing to read, understand and focus on material provided

• directors could control the information they received

• if there was information overload, board members should have prevented it

• if there was still a lot of material to digest, board members had to allow more time to read and understand it.

Further, some committee members advised us that they do not read all the papers because, as experienced committee members, they know what to focus on. This highlights the importance for audit committees and agencies reviewing as a priority the volume and quality of information provided to committee members prior to each meeting.

Keeping members informed about the agency

Audit committee members must also be kept abreast of developments affecting the agency in areas such as risk management, program management, information

management and security, performance measurement, and financial management and reporting.

Across the audited agencies, several mechanisms are used to ensure audit committee members are kept informed:

• A rolling program of briefings by senior executives at each audit committee meeting to provide an overview of their division—the majority of audit committees we examined schedule 20–30 minute presentations by senior executives at each meeting. Some agencies provide templates for these presentations, to help senior executives align their updates with the corporate plan and outline key priorities, opportunities and challenges for the future, as well as noting how the business unit is tracking against strategic risks and audit recommendations. This helps audit committees to receive high-value

• Regular meetings between the secretariat and independent members— independent members of the Victoria Police audit committee have bimonthly meetings with the secretariat, internal audit team and chief risk officer to discuss emerging issues in the sector.

• Forwarding organisational updates out of session—independent members at DELWP, DHHS and DPC receive copies of departmental communications from the secretary.

• Inviting independent members to attend key organisational events— independent members at DJR were invited to attend the risk resilience awards, which are annual awards given across the department for special achievements in inculcating a culture of risk awareness and making the most of opportunities that arise.

2.4.2

Planning for and conducting meetings

Annual forward plan—addressing each charter responsibility

Audit committees must comply with all aspects of their charter responsibilities throughout the year. The 2016 Standing Directions removed the requirement for audit committees to develop an annual work program, but it is generally considered a minimum requirement for audit committees to develop an annual forward meeting schedule that includes the dates and agenda items for each meeting. This schedule should cover all the responsibilities outlined in the committee’s charter. This is particularly important, as noted by the ANAO better practice guidance, in an

environment where agencies are seeking a greater level of assurance and advice from audit committees, especially with the increasing complexity of agency responsibilities. All audited agencies except Victoria Police had an annual work program for their audit committees. However, not all of these work programs appeared to be clearly mapped to all aspects of the committee’s charter responsibilities. While the DHHS 2015–16 work plan did not specifically cross-reference the charter at all, the department noted that it will include this for the 2016–17 annual forward plan.

To ensure that all charter responsibilities are addressed throughout the year, agencies should clearly set out the audit committee annual plan in a way that references each responsibility, as shown in Figure 2H.

Audit committee governance and operations

Figure 2H

Sample audit committee annual plan referencing charter responsibilities

Charter responsibility

and reference Meeting 1 Meeting 2 Meeting 3 Meeting 4

1.1 ……….. Agenda item 1 Agenda item 2 Agenda item 4

1.2 ……….. Agenda item 1

2.1 ……….. Agenda item 4 Agenda item 2 Agenda item 3 Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Setting the agendas and conducting meetings efficiently

Meetings should be well planned and structured in a way that allows the committee to make the most of its time together. Meeting agendas are generally settled by the chair, together with the committee secretariat, based on the annual forward plan and any other arising matters. We found a number of good practices at several committees:

• The chair ensures that agenda items are prioritised for each meeting so that the most important items are discussed first. This helps to ensure that members are fresh and that, if the meeting runs out of time, the most important items are not missed.

• Agenda items are marked for ‘discussion’, ‘presentation’, ‘endorsement’ or ‘noting’ to provide clear direction to the members.

• Any in-camera sessions (private meetings with the internal or external auditors and the committee members, excluding agency management) are held

15 minutes before the official start of the meeting, so that departmental staff are not left waiting.

Many audit committee members supported the practice of streamlining meetings by limiting or excluding presentations on agenda items that are taken as read. Many members noted that these presentations do not add to the content but take up a lot of time that could be used for more meaningful discussion.

As a further step, audit committees can streamline their meetings and focus on substantive issues by using ‘consent agendas’, where routine, procedural,

informational and self-explanatory and/or non-controversial items are presented to the committee in a single motion and only discussed in detail if requested by members.

2.5

Effective evaluation of audit committee

performance

2.5.1

Audit committee self-assessments

Both the 2003 and 2016 Standing Directions require audit committees to self-assess their performance annually. DELWP, DHHS and DEDJTR were impacted by

machinery-of-government changes, meaning their committees in their current form have only been in place since early 2015. As a result, there has only been enough time for one self-assessment:

• In 2015, DELWP audit committee members evaluated the performance of the committee against its charter and the action plan developed from the evaluation of the former Department of Environment & Primary Industries (DEPI) audit committee. Outcomes were discussed at the committee’s strategic planning workshop in October of the same year.

• The DHHS audit committee completed a self-assessment in 2015.

• DEDJTR’s audit committee is in the process of conducting its first self-assessment, due to be tabled in August 2016.

Audit committees from the agencies that were not subject to the

machinery-of-government changes—DET, the Department of Treasury & Finance, DJR and Victoria Police—undertake annual self-assessments.

Moving forward, agencies should be aware that the guidance accompanying the 2016 Standing Directions notes that, at a minimum, agencies should consider as part of their annual self-assessments:

• the effectiveness of the audit committee as a whole

• the performance of individual audit committee members (for external members, performance criteria may be included in their letter/contract of engagement; and for agency staff, performance criteria may be included in their performance plans)

• compliance with the audit committee’s charter.

2.5.2

Agency reviews of the committee performance

The 2016 Standing Directions require agencies to formally review the performance of the audit committee at least once every three years. While not a specific requirement under the 2003 Standing Directions, two agencies have commissioned reviews of their audit committee’s performance in its current form. Both reviews were undertaken by an independent contractor.

Audit committee governance and operations

Two other agencies are planning to undertake agency reviews by early next year:

• DELWP intends to continue the practice of its predecessor department (the Department of Environment and Primary Industries), alternating audit committee self-assessments one year with agency reviews of the committee’s performance the next year. DELWP’s first agency assessment, to be undertaken by an independent contractor, is scheduled for tabling in October 2016.

• DJR is planning to review its audit committee’s performance in February 2017.

Recommendations

That agencies:

1. develop and maintain mechanisms to identify the appropriate mix of skills and experience needed for audit committee membership and to identify any gaps 2. ensure that annual work programs cover each audit committee charter

responsibility

3. work with the audit committee to better define, or refine, the committee’s information needs, including whether reported information is reliable and understandable

4. align audit committee meeting materials and agendas with priority areas 5. conduct formal reviews of the performance and independence of independent

audit committee members before reappointing them for additional terms

6. consider offering continuing education that addresses topics relevant to the audit committee’s needs

7. work with the audit committee to evaluate whether it has the capacity to fully acquit its obligations under the Standing Directions and charter, or whether there is a need to review its role, structure and/or operational arrangements.

3

Oversight of risk

management

At a glance

Background

One of the primary tasks of an audit committee is to provide independent oversight of and advice on the agency’s risk management framework.

Conclusion

Audit committees must maintain oversight of agency-wide risks, despite the narrowed focus of the 2016 Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance (Standing Directions). This is because the 2016 Standing Directions mandate the application of the Victorian Government Risk Management Framework, and audit committees need to verify agencies’ compliance with these requirements.

Of the three examined audit committees, two had fulfilled the requirements of the Standing Directions and their charters to oversee risk management. They were supported by consistent risk reporting, and there is evidence that the audit committees improved their agency’s risk management.

The third audit committee has been hampered by inconsistent risk management practices across the agency and unclear risk governance responsibility. The agency is working to address this.

Recommendations

That agencies:

• ensure that the risk oversight responsibilities of the audit committee are clear and that its role is supported by consistent risk reporting

• consider whether audit committee minutes should include relevant elements of the committee’s discussion to transparently demonstrate the committee’s performance.