REVIEW ARTICLE

Assessment of Asthma Severity and Asthma Control

in Children

Barbara P. Yawn, MD, MSca, Susan K. Brenneman, PhDb, Felicia C. Allen-Ramey, PhDb, Michael D. Cabana, MD, MPHc, Leona E. Markson, ScDb

aDepartment of Research, Olmsted Medical Center, Rochester, Minnesota;bOutcomes Research and Management, Merck & Co, Inc, West Point, Pennsylvania;cDivision of

General Pediatrics, University of California, San Francisco, California

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

ABSTRACT

National and international guidelines for asthma recommend the assessment and documentation of severity as the basis for patient management. However, studies show that there are problems with application of the severity assessment to children in clinical practice. More recently, asthma control has been introduced as a method to assess the adequacy of current treatment and inform asthma man-agement. In this article we review the application and limitations of the severity assessment and the asthma-control tools that have been tested for use in children. A system of using asthma severity for disease assessment in the absence of treatment and using asthma-control assessment to guide management decisions while a child is receiving treatment appears to be a promising approach to tailor treatment to improve care and outcomes for children with asthma.

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/ peds.2005-2576

doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2576

Key Words

asthma, assessment, asthma severity, asthma control, children

Abbreviations

NAEPP—National Asthma Education and Prevention Program

GINA—Global Initiative for Asthma FEV1—forced expiratory volume in 1

second

ATAQ—Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire

ACT—Asthma Control Test

Accepted for publication Jan 19, 2006

Address correspondence to Barbara P. Yawn, MD, MSc, 210 Ninth St SE, Olmsted Medical Center, Rochester, MN 55904. E-mail: yawnx002@umn.edu

A

STHMA IS THEmost common chronic childhood ill-ness, affecting⬎4.8 million children in the United States and resulting in high levels of preventable mor-bidity and mortality.1National and internationalguide-lines for asthma have been published to assist in man-aging this common disease.2–8

A fundamental component of the asthma guidelines is the assessment of asthma “severity” used to describe the underlying disease state. Guidelines link the assessed level of asthma severity to appropriate medications, the frequency and methods of monitoring symptoms, lung function, a patient’s educational needs, and content of an asthma action plan. Studies of physicians’ care of asthma have shown incomplete adoption of the asthma guidelines.9–15 The challenges in understanding and

translating the guidelines into clinical practice and on-going clinical management of asthma seem to be reasons for the gaps in guideline adoption.16,17

More recently, asthma “control,” defined as the patient’s response to his or her current asthma man-agement, has been introduced as a method to assess adequacy of current treatment and inform asthma man-agement. Control is assessed while the patient is being treated and, therefore, may be easier for clinicians, pa-tients, and parents to understand and incorporate into asthma-management plans.

In this article we review the evolution and limitations of the concepts of severity and control in children with asthma and highlight potential barriers that may need to be overcome for these concepts to be translated into routine primary care. The review is based on the pub-lished medical literature as well as the authors’ experi-ence in trying to adopt current asthma-management recommendations for primary care practice. We searched Medline for relevant English-language articles using the search terms “asthma and children,” “asthma and severity,” “asthma and control,” “asthma measure-ments,” “FEV,” “pulmonary function test,” “patient management,” and “disease management” for literature published between 1996 and July 2005. Additional sources included key references cited in these articles,

national and international guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma, and other references iden-tified.

MEASUREMENT OF ASTHMA SEVERITY

The Evolution of Measurement of Asthma Severity

The concept of asthma severity has evolved since first being published with the 1991 National Asthma Educa-tion and PrevenEduca-tion Program (NAEPP) guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. The original 1991 severity classification separated asthma into mild, mod-erate, and severe categories on the basis of symptoms, frequency of exacerbations, and (for children) school attendance. The degree of exercise tolerance (good, di-minished, and very poor) and pulmonary function tests were also included in the severity assessment, all mea-sured before asthma treatment was begun. After treat-ment was established, severity could also be assessed by the response to and duration of therapy. The character-istics for each severity level were reported to be “gen-eral” and, because of the variable nature of asthma, a patient’s disease could overlap⬎1 severity category.2

The 1997 version of the NAEPP asthma guidelines2

introduced the concept of intermittent and persistent asthma with 4 categories: mild-intermittent, mild-per-sistent, moderate-persistent, and severe-persistent asthma (Table 1). The severity classification was based on symptom frequency (daytime or nighttime), activity limitations, peak expiratory flow, and day-to-night peak-flow variability, again all before treatment. Sever-ity was assigned on the basis of the highest category reached for any measure. For children under 5 years of age, only symptom data were used for the severity as-sessment. How severity was to be assessed and modified over time was unclear. The 2002 update of the NAEPP guidelines did not modify the severity classification.3

Other groups have modified the NAEPP guidelines in an attempt to expand measures of severity to include severity assessment on the basis of the type of current treatment and the presence of symptoms while on

treat-TABLE 1 Classification of Asthma Severity According to Clinical Features Before Treatment2,4

Symptoms Nocturnal

Symptoms

Lung Function

Step 1: mild-intermittent ⱕ2 times per wk; asymptomatic and normal PEF between exacerbations; exacerbations brief

ⱕ2 times per mo FEV1or PEFⱖ80% predicted; PEF variability⬍20%

Step 2: mild-persistent ⬎2 times per wk but⬍1 time per d; exacerbations may affect activity

⬎2 times per mo FEV1or PEFⱖ80% predicted; PEF variability 20%–

30% Step 3: moderate-persistent Daily symptoms; exacerbations may affect

activity and sleep; exacerbationsⱖ2 times per wk: may last days; daily use of short-acting2agonist

⬎1 time per wk FEV1⬎60% to⬍80% predicted; PEF variability⬍30%

Step 4: severe-persistent Symptoms daily; limited activity; frequent exacerbations

Frequent FEV1or PEFⱕ60% predicted; PEF variability⬎30%

ment.4–7 For example, the Canadian guidelines6

recom-mend that, after asthma treatment has begun, severity be assessed on the basis of the level of medication needed to keep asthma symptoms and pulmonary func-tion measurements within a prespecified level. The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines4also

rec-ommend a measure of severity that is based on daily medication regimen and response to treatment.

Applying Severity to Asthma Practice: Limitations and Gaps

The concept of severity remains important for determin-ing the initial level or step of asthma therapy, initiatdetermin-ing communication and education with children and par-ents, selecting the immediacy of follow-up, and enroll-ing patients into research studies. Once a patient is treated, its value is less clear. Lack of clarity regarding when to change the severity assignment, how to incor-porate the frequency and intensity of exacerbation into the severity assessments, or how to measure severity in treated patients limits the utility of asthma-severity as-signment in clinical practice. For children, this is a par-ticularly troubling issue, because as they grow and de-velop, it is not known whether their baseline condition will tend to stay the same, get worse, or get better. Increasing evidence that the underlying disease is dy-namic and variable makes a static asthma-severity clas-sification for a patient at a single point in time mislead-ing and not helpful in adjustmislead-ing therapy.18,19

Classifying asthma severity has been shown to have limited reproducibility among both primary care and childhood asthma specialists,9,20 and the distinction

be-tween severity-classification levels has not been vali-dated as clinically important or relevant. These prob-lems, as well as the variable nature of asthma, may have undermined physicians’ belief and confidence in the utility of this aspect of the tool. Furthermore, it is un-clear whether the cut points for frequency of symptoms or lung function used to grade severity apply equally to children and adults.

Inadequate appraisal of symptom intensity and fre-quency may contribute to underutilization of the asth-ma-severity assessment.21–23 Factors that may affect

ap-praisal and interpretation of symptoms include intensity, episodicity or chronicity of illness, psychological vari-ables such as denial or defensive style, parent-child in-teraction, level of child development, and intelli-gence.24–26 Symptom appraisal in younger children is a

unique challenge, because children may not be aware of symptoms, capable of verbalizing asthma symptoms, or able to recall symptom information to the same extent as older children or adults.27 Events occurring in the time

directly before clinical examination are perhaps most salient to younger children (ie, ⬍8 –10 years old), whereas the parent may be better at reporting patterns of symptoms over time.28The presence of a parent

dur-ing a visit may also affect what the child can or wishes to

recall. Even as children age and gain knowledge about their condition, parent and child perceptions about asthma symptoms are not consistent.29Data show that

parents and school-aged children report differing levels of symptoms and medication use.30,31Some of these

dif-ferences are anticipated, because parents seldom accom-pany their children to school or play and seldom sleep in the same room. The youngest age at which children begin to be the best source of symptoms is difficult to determine; therefore, the preschool-aged child may be the secondary source of information, whereas the par-ents become the secondary source in older school-aged children and adolescents.

Currently, only one objective measure is included in the severity assessment: pulmonary function testing. The availability of inexpensive and portable spirometry equipment has made measurement of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), FEV1/forced vital capacity

ratios, and reversibility theoretically feasible in the pri-mary care office. Yet, the value of lung function test results for informing severity assessment in children is controversial. Few children can adequately complete forced expiratory maneuvers such as spirometry before the age of 5, with most being able to do so by 7 years of age.2,32,33Even when testing is feasible, several studies

have found inconsistent or poor relationships between FEV1 and asthma symptoms in children, because most

children have near-normal FEV1values even when they

are markedly symptomatic.34–39The NAEPP FEV

1values

reported to distinguish between mild, moderate, and severe-persistent asthma are based on experts’ opinions and, in light of new study results, may need to be cali-brated differently for adults and children.34,40Emerging

technologies show promise as objective clinical measures of asthma disease activity and, therefore, underlying severity but have not been validated for treatment deci-sion-making.41–45 Therefore, in children it seems that

self-reported or parent-reported information is the main resource for assessing disease status.

Another challenge with the current severity-classifi-cation system is the failure to address exacerbations and exercise-associated problems. Disease-severity assess-ment may be misrepresented as mild in a child with life-threatening asthma exacerbations or severe exer-cise-induced symptoms but who is otherwise asymptom-atic. The same problem with underestimating disease burden can occur when assessing severity in seasonal asthma during asymptomatic periods. A static severity assessment that is performed at a single point in time often misses important aspects of the patient’s experi-ence with his or her asthma.

guide-lines.9,46,47These difficulties in applying the

asthma-se-verity assessment within clinical practice (the lack of correlation between lung function and symptoms, the variable nature of asthma, the inability to determine severity posttreatment, and the common failure to assess symptom frequency) have fostered an increasing interest in moving from severity assessment after the initial dis-ease assessment to a measure more consistent with the goals of asthma management, namely assessment of symptom and disease burden and the impact of treat-ment on disease burden.

MEASUREMENT OF ASTHMA CONTROL

The concept of asthma control is also evolving. In 1996, Cockcroft and Swystun48emphasized that asthma

con-trol is related to the appropriateness of therapy. Subse-quent reviews of the concept of asthma control have emphasized that asthma control is a short-term evalua-tion of the adequacy of patient management and deter-mines the need for clinical intervention.49,50Thus,

con-trol is a function of underlying severity plus the adequacy of management.49The primary goals of asthma

treatment according to the guidelines are identical for patients regardless of disease severity. Although no spe-cific method of asthma-control assessment is specified, the goals in current guidelines reflect asthma control: minimal or no symptoms, minimal or no use of rescue medication, no activity limitations, and (near) normal lung function with no adverse treatment effects.

Methods for Measuring Control

Several validated instruments for assessing asthma con-trol are currently available, each capturing multiple as-pects of asthma burden. Unlike severity scores, which are clinician derived, most control scores are based on patient- or parent-completed surveys51–57 or a daily

dia-ry.58Bateman et al59derived a measure of asthma control

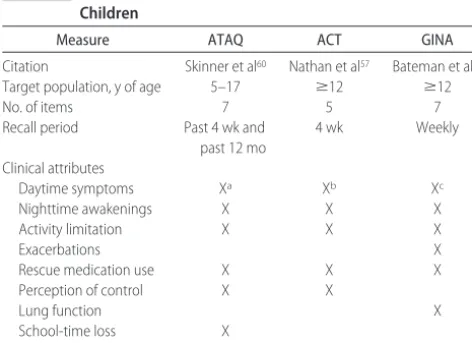

by assigning numerical values to the elements of the GINA treatment goals. Most control measures have been studied in adults with only the Asthma Therapy Assess-ment Questionnaire (ATAQ), the Asthma Control Test (ACT), and the guideline-based control measure being studied in children.

The ATAQ for children and adolescents is a brief questionnaire designed for completion by parents of children aged 5 to 17 years.60 The ATAQ instrument

includes questions regarding several aspects of asthma management in addition to asthma control, including satisfaction with patient-provider communication, pa-tient attitudes and behaviors, and perceived self-efficacy. The instrument was designed to assist clinicians and health plans with identifying children with poorly con-trolled asthma who may be candidates for additional asthma-management support. Asthma control is as-sessed by using 7 questions about recent (past 4 weeks) or chronic (past 12 months) symptoms and

conse-quences of asthma. For each completed survey, a score of 0 on the control domain indicates no control issues, and a nonzero score suggests control problems. Through a cross-sectional survey involving 3 managed care orga-nizations, Skinner et al60found that the ATAQ

demon-strated good internal consistency and strong relation-ships with existing validated measures of childhood health status, asthma impact, and health care utilization. The ATAQ has been used in a variety of other studies investigating the care of children with asthma.11,61–66

Im-plementation of the ATAQ into clinical practice for chil-dren requires development of a system to obtain the ATAQ score and determine how it will be linked to treatment modifications.65,67

The ACT was developed as a population-screening and -monitoring tool.57 The 5-item self-administered

survey is designed for use by patients 12 years of age and older. The ACT is scored by summing responses for each of 5 items, referring to the past 4 weeks, to produce a final score ranging from 5 (poor control) to 25 (complete control). A score ofⱕ19 points indicates that a patient’s asthma may not be controlled. Studies68,69including

chil-dren 12 to 17 years of age have reported significant correlations between the ACT score and changes in asthma control as measured by physician global ratings and FEV1values. In addition, study results highlight the

ability of ACT to identify high-risk adolescent patients with or without the use of lung function testing.69 As

with the ATAQ, little information describing the use of this tool in clinical decision-making in everyday practice has been published.

In an effort to closely link the GINA and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute asthma guidelines with an operational definition of asthma control, Bateman et al59defined 3 potential levels of asthma control (totally

controlled, well controlled, or uncontrolled) that could be achieved by patients with asthma of varied severity levels. Results of a 1-year randomized, parallel-group study including patients 12 years of age or older revealed that asthma control can be achieved and maintained with intensive intervention. Data specifically describing the utility or feasibility of using of this guideline-based control assessment in adolescents and children was not presented. No formal validation work or specific control measure development using this methodology has been reported.

In comparison to composite asthma-control question-naires, when a single global question about control is asked, both children and parents have been found to overestimate the level of control.69,70 One study also

showed that selection of asthma-control criteria among physicians varies and is not always compatible with asthma guidelines.70In each of these studies, inclusion of

instru-ments for assessment of asthma control in children and adolescents is provided in Table 2.

At the time of this writing, several new instruments in this area were noted, although no formal validation work has been published.71–73

Limitations and Gaps in Assessing Control

The primary means of assessing asthma control is through patient self-report of symptom severity and fre-quency, functional limitations, and use of rescue medi-cation. Similar to the symptom assessment in classifica-tion of severity, it is necessary to decide who should be the primary source of information (parent, child, or caregiver) about disease status, impact of disease on daily life, current use of medications, and existence or concerns about treatment adverse effects.

In contrast to severity assessment, which is designed to be conducted in the office and usually by the physi-cian, asthma-control assessments can be done by pa-tients, parents, or guardians in the office or at home. Regular office visits are infrequent for many children with asthma, resulting in a lack of information on symp-toms and asthma-burden variability. Self-completed asthma-control measures offer the potential to use the assessment of control outside the office setting, with certain results triggering additional clinical follow-up. Protocols for how to incorporate control assessment in this manner have yet to be established.

Although asthma control provides a different method to view a patient with asthma, it fails to incorporate patient-specific goals of treatment or desired level of control. The significance of the control assessment to the child is not known. Children may be most interested in playing soccer without breathing problems or keeping

their pets in the bedroom with them at night. The clini-cian may still need to translate the control assessment into terms that are meaningful to children and their caregivers. Assessment of control should lead to action, and few control measures suggest specific actions other than increasing the medication dose or adding another class of medication. They fail to incorporate measures of adherence, appropriate medication use, and trigger iden-tification and avoidance. All national and international asthma guidelines include these issues, in addition to pharmacologic measures, as required components of op-timal asthma management. Unfortunately, current con-trol measures do not provide specific direction to clini-cians on how to link the control scores to the patients’ educational, pharmacologic, or nonpharmacologic needs.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TREATING CHILDHOOD ASTHMA

Approaches for assessments that guide the management of childhood asthma have been in constant evolution. The 1991 development of the empirically based asthma-severity assessment was the first step in translating asthma research into guidelines and patient care. Although the empirically based severity assessment continued to be the basis for the 2002 US guideline update,2,3,74other

available guidelines have chosen alternative approaches that acknowledge the impact and burden of asthma.4–6,8

Yet, even with asthma control as an integral part of asthma-burden assessment, many of the same issues remain: how and when to use and evaluate the meaning of lung function parameters in children, the best ap-proach to symptom assessment, and the determination of appropriate levels of both initial and subsequent treat-ment.

Our review of the literature shows that the assess-ment of severity continues to be important for the initial diagnosis, assessment of the disease process, and treat-ment decisions. However, once treattreat-ment is initiated, the goal is asthma control, including both disease activity and symptom manifestation. Although only a few of the currently available instruments to measure control have been tested for use in children, the incorporation of a control measure within clinical practice has distinct ad-vantages. First, the use of such a tool ensures regular assessment of the elements of control. Second, comple-tion of the control measure can be facilitated by health care personnel other than physicians, thereby ensuring that the data are collected and relieving the physician-specific burden while facilitating a physician-patient partnership.75 Third, consistent questioning of control

elements at each office visit will train the child and/or the parent to anticipate what symptoms and experiences are important for the management of their asthma. Fourth, the instruments can be completed periodically between office visits so that the variability and changing nature of asthma can be captured.

Finally, the concept of control is “patient focused.” TABLE 2 Summary of Asthma-Control Measures for Use With

Children

Measure ATAQ ACT GINA

Citation Skinner et al60 Nathan et al57 Bateman et al59

Target population, y of age 5–17 ⱖ12 ⱖ12

No. of items 7 5 7

Recall period Past 4 wk and

past 12 mo

4 wk Weekly

Clinical attributes

Daytime symptoms Xa Xb Xc

Nighttime awakenings X X X

Activity limitation X X X

Exacerbations X

Rescue medication use X X X

Perception of control X X

Lung function X

School-time loss X

Adverse events X

aFrequency of wheezing or difficulty breathing when exercising and wheezing during the day

when not exercising.

bFrequency of shortness of breath.

cSymptom score based on frequency, length, and impact of asthma symptoms (nonspecific)

Patient self-management decisions as well as the pa-tients’ beliefs regarding diagnosis, prognosis, and the efficacy, necessity, and safety of therapy affect asthma control. It is not clear that any of the available asthma-control assessment tools capture all of this information effectively and efficiently. To develop patient-centered goals and treatment plans, physicians and patients must have additional interactions beyond simple completion of a control measure. However, an asthma-control as-sessment provides a good starting point for these con-versations.76

Currently, there is a gap in the ability of primary care practices to translate the asthma care evidence and guidelines into practice. Therefore, in addition to deter-mining the clinical validity of both asthma severity for initial assessment and asthma-control measures for lon-gitudinal care of children, it will also be necessary to develop tools, systems, and clinical imperatives to collect the information required. Guideline developers should offer specific tools or methods to assess control, remov-ing the burden of development and risk of nonunifor-mity from the individual practices.

CONCLUSIONS

The choice of medications and recommendations for further care reflected in guidelines is typically based on the assessed and documented frequency and impact of asthma symptoms, the modification of functional status, and the use of current medications.30,61,65–66,76,77A plan of

asthma care that includes the use of severity assessment initially and thereafter a patient-focused approach of control assessment is likely to lead to better assessment of the impact of asthma, better patient adherence, and a tailored asthma-management plan appropriate to indi-vidualized clinical assessment.

REFERENCES

1. Mannino DM, Homa DM, Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Gwynn C, Redd SC. Surveillance for asthma: United States, 1980 –1999.MMWR Surveill Summ.2002;51(1):1–13

2. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Asthma Ed-ucation and Prevention Program.Expert Panel Report 2: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda, MD: Na-tional Institutes of Health; 1997. NIH Publication 97-4051 3. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Asthma

Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 2 Update: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2002. NIH Publi-cation 02-5074

4. Global Initiative for Asthma.Global Strategy for Asthma Manage-ment and Prevention. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2004. NIH Publication 02-3659

5. Becker A, Lemiere C, Berube D, et al. Summary of recommen-dations from the Canadian Asthma Consensus guidelines, 2003.CMAJ.2005;173(6 suppl):S3–S11

6. Boulet LP, Becker A, Berube D, Beveridge R, Ernst P. Canadian asthma consensus report, 1999. Canadian Asthma Consensus Group.CMAJ.1999;161(11 suppl):S1–S62

7. Boulet LP, Bai TR, Becker A, et al. What is new since the last

(1999) Canadian Asthma Consensus guidelines?Can Respir J. 2001;8(suppl A):5A–27A

8. British Thoracic Society; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British guideline on the management of asthma. Thorax.2003;58(suppl 1):i1–i94

9. Doerschug KC, Peterson MW, Dayton CS, Kline JN. Asthma guidelines: an assessment of physician understanding and prac-tice.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.1999;159:1735–1741

10. Cabana MD, Bruckman D, Meister K, Bradley JF, Clark N. Documentation of asthma severity in pediatric outpatient clin-ics.Clin Pediatr (Phila).2003;42:121–125

11. Diette GB, Skinner EA, Markson LE, et al. Consistency of care with national guidelines for children with asthma in managed care.J Pediatr.2001;138:59 – 64

12. Senturia YD, Rosenstreich D, Bauman L. Pediatric primary care for asthma: how does the content of the office visit relate to NIH guidelines?Am J Respir Crit Care Med.1998;157:A540 13. Homer CJ. Asthma disease management.N Engl J Med.1997;

337:1461–1463

14. Wu AW, Young Y, Skinner EA, et al. Quality of care and outcomes of adults with asthma treated by specialists and generalists in managed care. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161: 2554 –2560

15. Legorreta AP, Christian-Herman J, O’Connor RD, Hasan MM, Evans R, Leung KM. Compliance with national asthma man-agement guidelines and specialty care: a health maintenance organization experience.Arch Intern Med.1998;158:457– 464 16. Cabana MD, Ebel BE, Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Rubin HR,

Rand CS. Barriers pediatricians face when using asthma prac-tice guidelines.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2000;154:685– 693 17. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Becher OJ, Rubin HR. Reasons for

pediatrician nonadherence to asthma guidelines.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2001;155:1057–1062

18. Calhoun WJ, Sutton LB, Emmett A, Dorinsky PM. Asthma variability in patients previously treated with beta2-agonists alone.J Allergy Clin Immunol.2003;112:1088 –1094

19. Yawn BP. The impact of childhood asthma on daily life of the family.Prim Care Respir J.2003;12:82– 85

20. Baker KM, Brand DA, Hen J Jr. Classifying asthma: disagree-ment among specialists.Chest.2003;124:2156 –2163

21. Halterman JS, Yoos HL, Kaczorowski JM, et al. Providers un-derestimate symptom severity among urban children with asthma.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2002;156:141–146

22. Yawn BP, Yawn RA. Measuring asthma quality in primary care: can we develop better measures?Respir Med.2006;100: 26 –33

23. Cabana MD, Slish KK, Nan B, Lin X, Clark NM. Asking the correct questions to assess asthma symptoms. Clin Pediatr (Phila).2005;44:319 –325

24. Fritz GK, McQuaid EL, Spirito A, Klein RB. Symptom percep-tion in pediatric asthma: relapercep-tionship to funcpercep-tional morbidity and psychological factors. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:1033–1041

25. Beausoleil JL, Weldon DP, McGeady SJ. Beta 2-agonist me-tered dose inhaler overuse: psychological and demographic profiles.Pediatrics.1997;99:40 – 43

26. Christie MJ, French D, Sowden A, West A. Development of child-centered disease- specific questionnaires for living with asthma.Psychosom Med.1993;55:541–548

27. Kuehni CE, Frey U. Age-related differences in perceived asthma control in childhood: guidelines and reality.Eur Respir J.2002;20:880 – 889

28. Fritz GK, Yeung A, Wamboldt MZ, et al. Conceptual and meth-odologic issues in quantifying perceptual accuracy in childhood asthma.J Pediatr Psychol.1996;21:153–173

Chil-dren and adult perceptions of childhood asthma. Pediatrics. 1997;99:165–168

30. Yawn BP, Wollan P, Scanlon PD, Kurland M. Outcome results of a school-based screening program for undertreated asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol.2003;90:508 –515

31. Lara M, Duan N, Sherbourne C, et al. Differences between child and parent reports of symptoms among Latino children with asthma. Pediatrics. 1998;102(6). Available at: www. pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/102/6/e68

32. Beydon N, Pin I, Matran R, et al. Pulmonary function tests in preschool children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:640 – 644

33. Gorelick MH, Stevens MW, Schultz T, Scribano PV. Difficulty in obtaining peak expiratory flow measurements in children with acute asthma.Pediatr Emerg Care.2004;20:22–26 34. Paull K, Covar R, Jain N, Gelfand EW, Spahn JD. Do NHLBI

lung function criteria apply to children? A cross-sectional eval-uation of childhood asthma at National Jewish Medical and Research Center, 1999 –2002. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;39: 311–317

35. Fuhlbrigge AL, Kitch BT, Paltiel AD, et al. FEV(1) is associated with risk of asthma attacks in a pediatric population.J Allergy Clin Immunol.2001;107:61– 67

36. Eid N, Yandell B, Howell L, Eddy M, Sheikh S. Can peak expiratory flow predict airflow obstruction in children with asthma?Pediatrics.2000;105:354 –358

37. Bacharier LB, Strunk RC, Mauger D, White D, Lemanske RF Jr, Sorkness CA. Classifying asthma severity in children: mismatch between symptoms, medication use, and lung function.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2004;170:426 – 432

38. Horak E, Grassl G, Skladal D, Ulmer H. Lung function and symptom perception in children with asthma and their par-ents.Pediatr Pulmonol.2003;35:23–28

39. Spahn JD, Cherniack R, Paull K, Gelfand EW. Is forced expi-ratory volume in one second the best measure of severity in childhood asthma?Am J Respir Crit Care Med.4;169:784 –786 40. Klein RB, Fritz GK, Yeung A, McQuaid EL, Mansell A.

Spiro-metric patterns in childhood asthma: peak flow compared with other indices.Pediatr Pulmonol.1995;20:372–379

41. Colon-Semidey AJ, Marshik P, Crowley M, Katz R, Kelly HW. Correlation between reversibility of airway obstruction and exhaled nitric oxide levels in children with stable bronchial asthma.Pediatr Pulmonol.2000;30:385–392

42. Covar RA, Szefler SJ, Martin RJ, et al. Relations between exhaled nitric oxide and measures of disease activity among children with mild-to-moderate asthma.J Pediatr.2003;142: 469 – 475

43. Rosias PP, Dompeling E, Dentener MA, et al. Childhood asthma: exhaled markers of airway inflammation, asthma con-trol score, and lung function tests.Pediatr Pulmonol.2004;38: 107–114

44. Napier E, Turner SW. Methodological issues related to exhaled nitric oxide measurement in children aged four to six years. Pediatr Pulmonol.2005;40:97–104

45. Pijnenburg MW, Hofhuis W, Hop WC, de Jongste JC. Exhaled nitric oxide predicts asthma relapse in children with clinical asthma remission.Thorax.2005;60:215–218

46. Cabana MD, Medzihradsky OF, Rubin HR, Freed GL. Applying clinical guidelines to pediatric practice.Pediatr Ann.2001;30: 274 –282

47. Roghmann MC, Sexton M. Adherence to asthma guidelines in general practices.J Asthma.1999;36:381–387

48. Cockcroft DW, Swystun VA. Asthma control versus asthma severity.J Allergy Clin Immunol.1996;98:1016 –1018

49. Vollmer WM. Assessment of asthma control and severity.Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol.2004;93:409 – 413

50. Fuhlbrigge AL. Asthma severity and asthma control:

symp-toms, pulmonary function, and inflammatory markers.Curr Opin Pulm Med.2004;10:1– 6

51. Juniper EF, O’Byrne PM, Guyatt GH, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure asthma control.Eur Respir J.1999;14:902–907

52. Jones K, Cleary R, Hyland M. Predictive value of a simple asthma morbidity index in a general practice population.Br J Gen Pract.1999;49:23–26

53. Boulet LP, Boulet V, Milot J. How should we quantify asthma control? A proposal.Chest.2002;122:2217–2223

54. Revicki DA, Leidy NK, Brennan-Diemer F, Sorensen S, Togias A. Integrating patient preferences into health outcomes assessment: the multiattribute Asthma Symptom Utility Index. Chest.1998;114:998 –1007

55. Vollmer WM, Markson LE, O’Connor E, et al. Association of asthma control with health care utilization and quality of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.1999;160:1647–1652

56. Vollmer WM, Markson LE, O’Connor E, Frazier EA, Berger M, Buist AS. Association of asthma control with health care utilization: a prospective evaluation.Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:195–199

57. Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol.2004;113:59 – 65

58. Juniper EF, O’Byrne PM, Ferrie PJ, King DR, Roberts JN. Measuring asthma control: clinic questionnaire or daily diary? Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2000;162:1330 –1334

59. Bateman ED, Bousquet J, Braunstein GL. Is overall asthma control being achieved? A hypothesis-generating study. Eur Respir J.2001;17:589 –595

60. Skinner EA, Diette GB, Algatt-Bergstrom PJ, et al. The Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire (ATAQ) for children and adolescents.Dis Manag.2004;7:305–313

61. Diette GB, Markson L, Skinner EA, Nguyen TT, Algatt-Bergstrom P, Wu AW. Nocturnal asthma in children affects school attendance, school performance, and parents’ work at-tendance.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2000;154:923–928 62. Bukstein DA, Luskin AT, Bernstein A. “Real-world”

effective-ness of daily controller medicine in children with mild persis-tent asthma.Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol.2003;90:543–549 63. Garcia Garcia ML, Wahn U, Gilles L, Swern A, Tozzi CA, Polos

P. Montelukast, compared with fluticasone, for control of asthma among 6- to 14-year-old patients with mild asthma: the MOSAIC study.Pediatrics.2005;116:360 –369

64. Dolan CM, Fraher KE, Bleecker ER, et al. Design and baseline characteristics of the epidemiology and natural history of asthma: Outcomes and Treatment Regimens (TENOR) study—a large cohort of patients with severe or difficult-to-treat asthma.Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol.2004;92:32–39 65. Patel PH, Welsh C, Foggs MB. Improved asthma outcomes

using a coordinated care approach in a large medical group.Dis Manag.2004;7:102–111

66. Algatt-Bergstrom PJ, Markson LE, Murray RK, Berger ML. A population-based approach to asthma disease management. Dis Manag Health Outcomes.2000;7:179 –186

67. Narayanan S, Edelman JM, Berger ML, Markson LE. Asthma control and patient satisfaction among early pediatric users of montelukast.J Asthma.2002;39:757–765

68. Schatz M, Mosen D, Apter AJ, et al. Relationship of validated psychometric tools to subsequent medical utilization for asthma.J Allergy Clin Immunol.2005;115:564 –570

69. Schatz M, Kosinski M, Sorkness C. Comparison of two patient-based measures of asthma control: ACT and ACQ. Proc Am Thorac Soc Int Conf. Philadelphia, PA: American Thoracic Society; 2005:A255

asthma control by physicians and patients: comparison with current guidelines.Can Respir J.2002;9:417– 423

71. Halterman JS, McConnochie KM, Conn KM, et al. A potential pitfall in provider assessments of the quality of asthma control. Ambul Pediatr.2003;3:102–105

72. GlaxoSmithKline, Inc; QualityMetrics, Inc. Childhood Asthma Control Test for children with asthma 4 to 11 years old. 2005. Available at: www.asthmacontrol.com/AsthmaControlTestChild. html. Accessed December 5, 2005

73. Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. SleepLearnPlay. Washington, DC: Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America; 2005

74. Gibson P. Asthma guidelines and evidence-based medicine. Lancet.1993;342:1305

75. Griffiths C, Foster G, Barnes N, et al. Specialist nurse interven-tion to reduce unscheduled asthma care in a deprived multi-ethnic area: the east London randomised controlled trial for high risk asthma (ELECTRA).BMJ.2004;328:144

76. Wolfenden LL, Diette GB, Krishnan JA, Skinner EA, Stein-wachs DM, Wu AW. Lower physician estimate of underlying asthma severity leads to undertreatment. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:231–236

77. Joseph CL, Foxman B, Leickly FE, Peterson E, Ownby D. Preva-lence of possible undiagnosed asthma and associated morbidity among urban schoolchildren.J Pediatr.1996;129:735–742 78. Bai J, Peat JK, Berry G, Marks GB, Woolcock AJ.

Question-naire items that predict asthma and other respiratory condi-tions in adults.Chest.1998;114:1343–1348

KINK IN FEDERAL LAW IS PROMPTING SCHOOLS TO STOP PICKING NITS: LAISSEZ-FAIRE APPROACH TO LICE MINIMIZES ABSENTEEISM, BUT IT DISTRESSES MOMS

“Education reform mandates like the No Child Left Behind law are putting a contentious new spin on a classroom issue that makes parents’ skin crawl: head lice. Schools used to take a hard line on the sesame-seed-sized parasites, which suck human blood and glue their eggs to individual hairs. At the first sign of an outbreak, pupils got scalp checks. Those with lice were immediately banished from the classroom until all lice and eggs— known as nits—were gone. But to the dismay of many parents, these ‘no nits’ policies are disap-pearing as school districts face state and federal pressure to reduce absentee-ism and boost academic achievement. No Child requires that 95% of students be present for mandatory achievement tests. It also allows states to use attendance to help determine whether school districts are making adequate educational progress under the federal law. Those that don’t do so face sanctions that could include state takeovers of their schools. At the Todd County Public Schools, a rural district based in Elkton, Ky., students found to have lice often used to miss a week or more of school. The old rules barred them from school until they could produce a letter from a doctor or a public-health agency certifying them lice- and nit-free. Under new guidelines adopted last year, a box top from an over-the-counter lice treatment does the trick.”

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2005-2576

2006;118;322

Pediatrics

and Leona E. Markson

Barbara P. Yawn, Susan K. Brenneman, Felicia C. Allen-Ramey, Michael D. Cabana

Assessment of Asthma Severity and Asthma Control in Children

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/118/1/322

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/118/1/322#BIBL

This article cites 65 articles, 11 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

ub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/allergy:immunology_s

Allergy/Immunology

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/asthma_subtopic

Asthma

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/pulmonology_sub

Pulmonology

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2005-2576

2006;118;322

Pediatrics

and Leona E. Markson

Barbara P. Yawn, Susan K. Brenneman, Felicia C. Allen-Ramey, Michael D. Cabana

Assessment of Asthma Severity and Asthma Control in Children

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/118/1/322

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.