How Readable Are Child Safety Seat Installation Instructions?

Mark V. Wegner, MD, MPH, and Deborah C. Girasek, PhD, MPH

ABSTRACT. Objectives. To measure the required

reading level of a sample of child safety seat (CSS) in-stallation instructions and to compare readability levels among different prices of CSSs to determine whether the lower cost seats to which low-income parents have greater access are written to a lower level of education.

Methods. A CD-ROM containing CSS installation in-structions was obtained from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Pricing information was obtained for available models from an Internet-based company that provides comparative shopping informa-tion. Paper copies of the instruction sets were generated, and their readability levels were determined using the SMOG test. A second rater was used in addition to the primary investigator to assess interrater reliability of the SMOG as applied to the instruction sets.

Results. The readability of instruction sets ranged from the 7th- to 12th-grade levels, with an overall mean SMOG score of 10.34. No significant associations were found to exist between readability and seat prices; this was observed whether the data were treated as continu-ous or categorical.

Conclusions. CSS instruction manuals are written at a reading level that exceeds the reading skills of most American consumers. These instruction sets should be rewritten at a lower reading level to encourage the proper installation of CSSs. Pediatrics 2003;111:588 –591; car seats, safety, installation, instructions, readability, chil-dren, injury prevention.

ABBREVIATIONS. MVC, motor vehicle collision; CSS, child safety seat; NHTSA, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

M

otor vehicle collisions (MVCs) are a leading cause of death in infants and children. In fact, in 1998, injuries resulting from MVCs accounted for 46% of all unintentional injury–related deaths among children aged 1 to 14.1Scientificevi-dence indicates that the single strongest risk factor for injury in an MVC is the nonuse of a restraint,2

with correctly used child safety seats (CSSs) reducing the risk of fatal injury by 71% and hospitalization by 67%.3 For child restraints to be optimally effective,

however, they must be installed correctly, yet we know from numerous studies that improper restraint

use is alarmingly prevalent, ranging from 79% to 94%.4 – 6

The underlying reasons for such a high rate of misuse of this important child safety device are not well understood. Possible contributors include engi-neering/design problems, physical difficulty with installation, and poor comprehension of installation instructions. Improvements in engineering and de-sign have been made over the years in an attempt to improve ease of use. Legislation has also been en-acted to improve uniformity and ease of installation, including the mandated development of upper tether straps and lower anchoring systems. As of September 2002, all new cars are required to feature these safety enhancements.7These advances will not

yield immediate benefits, however. Many older cars and CSSs will remain in circulation, particularly among lower-income families. Therefore, the com-prehensibility of current installation instructions is likely to influence parent compliance with this im-portant safety recommendation into the foreseeable future.

Poor comprehension often occurs when the re-quired reading level of a particular text exceeds the reading capacity of the target population. In this situation, patients often become fatigued and dis-couraged, which may affect compliance.8This issue

is important to consider when developing health-related instructions because illiteracy is a problem of great importance in the United States. A 1992 survey by the US Department of Education’s National Cen-ter for Education Statistics estimated that 21% of the adult population—⬎40 million Americans older than 16 years— had only rudimentary reading and writing skills (ie, they read at or below the fifth-grade level). Another 25% (50 million) were classified as being “marginally literate” (ie, they read at or below approximately the eighth-grade level). The survey also reported that people of lower socioeconomic status tend to have lower literacy levels.9It is

inter-esting to note that incorrect utilization of CSSs has also been correlated with a lower level of socioeco-nomic status.10

The impact of literacy on health has also been well documented in the literature,11and the readability of

health-related materials has been the subject of in-creasing scientific scrutiny.12–16We identified only 1

article that dealt with child safety and literacy, how-ever, and it did not address CSS installation.17

In this study, we measured the required reading level of CSS installation instructions to determine whether readability poses a potential barrier to cor-rect installation. An additional objective of the study

From the Department of Preventive Medicine and Biometrics, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland. Received for publication Nov 13, 2001; accepted Jul 22, 2002.

The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the US government.

Reprint requests to (D.C.G.) Department of Preventive Medicine and Bio-metrics, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, 4301 Jones Bridge Rd, Bethesda, MD 20814. E-mail: dgirasek@usuhs.mil

was to compare readability levels among different price categories of CSSs. The main reason for this second analysis was to determine whether the lower cost seats that are more accessible to low-income parents financially are also more accessible to them from the perspective of literacy.

METHODS Sample

The instruction sets used for the purposes of this study came from a CD-ROM distributed by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). “Manufacturers’ Instructions for Child Safety Seats 1999 Edition” became available in March 2001 and contains instruction sets for different manufacturers and mod-els current through 1999.18 NHTSA’s CD-ROM was chosen in

recognition of its comprehensiveness and uniformity. It included instruction sets for every major CSS manufacturer, as verified by cross-referencing lists obtained from the American Academy of Pediatrics, NHTSA, and SafetyBeltSafe U.S.A.19 –21The CD-ROM

features 140 different instruction sets, covering 11 manufacturers. Finally, the instruction sets represent materials on the market in 1 time frame (current through 1999).

Paper copies of all of the 140 instruction sets were generated with a laser printer. Certain exclusion criteria were then applied to generate our final study sample. Any instruction sets that dealt only with tether straps or harnesses were excluded because they were not specific to any particular model. Instruction sets unique to Canada were excluded. When there were multiple versions of US instruction sets for the same particular model on the ROM, only the most recent version was included. When apparent dupli-cates were undated, 1 of the sets was chosen at random to be tested. After these criteria were applied, each manufacturer on the CD-ROM was represented with at least 1 model, leaving a final sample for analysis of 107.

Pricing information for some of the CSS models was then obtained from epinions.com,22 an Internet-based company that

provides comparative shopping information for consumers. This source was chosen both for uniformity and for quantity of price information. Attempts to obtain pricing information from manu-facturers’ web sites were not successful because only a few con-tained pricing information. Of the numerous sources reviewed, epinions.com had pricing information for the most models in the study (n⫽35).

Measurement

The SMOG test was chosen for performing readability tests on the samples. The SMOG test was introduced by McLaughlin in 196923and has been used extensively to analyze health-oriented

literature. In addition, it is adaptable to small sample sizes. In-structions for how to perform the SMOG test were obtained from a National Institutes of Health publication.24The basic provisions

of the test include selecting 3 10-sentence samples (1 each from near the beginning, middle, and end of the desired text) and then counting the number of polysyllabic words (containing 3 or more syllables) in that sample. This information is then used to calculate the reading ability (measured as school grade reading level) re-quired for a person to comprehend that particular text.

For standardizing our sample of instruction text, 10 sentences in each of the following 3 distinct section types were tested for all sets: 1) the general warning section that preceded specific instruc-tions, 2) a section describing how to install the seat, and 3) a section dealing with finer points of installation, such as proper selection of seat belts or adjustment of harness straps. These sections were chosen as they related most closely to the issue of injury prevention. Headings were not tested unless they were part of a sentence. Pictures and diagrams were not considered, neither were captions that stood apart from the rest of the instruction set and applied only to pictures. Federal law25mandates that certain

language must be included in all instruction sets. These passages were tested separately from the instruction sets and were not included in our statistical analyses.

Although the SMOG test is a fairly objective test, it still allows room for subjectivity in measurement. Words such as “different” and “reference,” for example, are listed in the dictionary with 2-and 3-syllable pronunciations, necessitating a judgment call on the

part of a readability rater. To ensure that the test methods lent themselves to reliable administration, a second reviewer was used to apply the SMOG to approximately 25% of the instruction sets tested. This subset was selected by including the first instruction set from every manufacturer, and then including every fifth in-struction set from within each manufacturer. The second reviewer was given the same instruction set for the SMOG that was used by the principal investigator and tested the same passages.

Statistical Analysis

SMOG scores as well as available pricing information for each CSS model were analyzed using SPSS (Release 10.0.5).26 Basic

descriptive statistics were generated, including mean readability level overall and mean readability by manufacturer, with 95% confidence intervals for samples larger than 10.

When examination of available data did not suggest any obvi-ous price cutoff points, the samples were divided into the lower, middle, and upper thirds using a Microsoft Excel27spreadsheet.

This trifurcation resulted in categories labeled low ($80 or less), medium ($81–$116), and high (⬎$116). A Kruskal-Wallis test was then used to determine whether the readability of the instructions varied by CSS price category. Prices were also treated as contin-uous data and analyzed using a nonparametric correlation.

For exploring whether brand or model names that consisted of 3 or more syllables (eg, “Century,” “Champion Scout Trooper”) had biased the grade level of these samples, a Mann-Whitney test was performed. For determining reliability of the SMOG, a

statistic was calculated to compare the scores of the 2 raters.

RESULTS

The readability scores of the installation instruc-tions we tested ranged from 7th to 12th grade, with a median and mode of 10 (see Table 1 for a frequency distribution of scores). The overall mean SMOG readability score was 10.34 (95% confidence interval: 10.16 –10.52). The SMOG range varied by manufac-turer: 7 to 12 (Britax, Charlotte, NC), 8 to 12 (Kolcraft, Chicago, IL), 9 to 11 (Evenflo, Piqua, OH), 9 to 12 (Cosco, Columbus, IN; Century, Macedonia, OH), 10 to 11 (Graco, Exton, PA), 10 to 12 (Fisher-Price, East Aurora, NY), and 11 to 12 (Guardian). When evalu-ated separately, the wording sections required by federal regulation also tested at the 10th-grade level. For the instruction sets for which pricing informa-tion was available (n⫽35), the mean price was $109 with a range of $58 to $270. A Kruskal-Wallis test did not show any significant difference in readability among the 3 price categories that we created (P ⫽

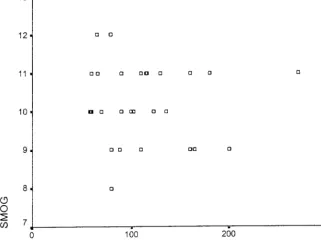

.80). Readers who are interested in reviewing a com-plete listing of readability scores and pricing infor-mation for each model tested may contact the au-thors for more information. The raw price data were also plotted against SMOG score (Fig 1). When the price information was analyzed in its original con-tinuous form, a Spearman rank correlation of price versus readability yielded similar (ie, nonsignificant) results (r⫽ ⫺0.04,P⫽.82).

When analyzed separately models for which either the manufacturer or the model name or both had⬎3

TABLE 1. Frequency Distribution of SMOG Scores SMOG Score Frequency % Cumulative %

7th grade 1 0.9 0.9

8th grade 2 1.9 2.8

9th grade 14 13.1 15.9

10th grade 42 39.3 55.1

11th grade 39 36.4 91.6

12th grade 9 8.4 100.0

ARTICLES 589

at Viet Nam:AAP Sponsored on August 30, 2020 www.aappublications.org/news

syllables (n⫽65) and had a mean readability score of 10.34 and a median of 10.0. Those with shorter names (n⫽42) had a mean score of 10.33 and a median of 10.5. When a Mann-Whitney test was applied, this small difference between the 2 groups was not sta-tistically significant.

Of the 29 samples tested by both the primary researcher and a second reviewer, agreement was achieved on 25 of 29 samples, resulting in astatistic of 0.80 (P⬍ .001).

DISCUSSION

Our data indicate that CSS instructions in the United States are currently written at a reading level that is too high. Experts in the arena of health literacy recommend that materials be targeted to the fifth- or sixth-grade reading level.8,11The average readability

level of the instruction sets that we tested was 10th grade. Researchers in a Louisiana study found that approximately two thirds of parents tested in an outpatient clinic could not read at more than a ninth-grade level.14Because parents would be expected to

be the main target audience for CSS instruction sets, this lends additional evidence that the instruction sets may not be reaching the people most likely to benefit from the message.

Overall, there did not seem to be any significant difference in readability among different price cate-gories. This suggests that manufacturers are not tar-geting instructions to different market segments, at least with regard to reading level.

This study did not take into account some factors that tend to increase comprehensibility, such as the use of illustrations and empty space.8The main

rea-son this was not done was because images that were generated from the CD-ROM lost resolution.

In addition, parents may not even read the instruc-tion manuals that come with their CSS or may re-ceive second-hand seats that come without instruc-tions, so the importance of instructions in the proper installation of CSS is unclear. In focus groups spon-sored by the NHTSA, however, parents reported referring to written instructions when they ran into difficulties.28

Education efforts combined with recent engineer-ing advances can be important complements of CSS instruction sets. With regard to newborns, the Amer-ican Academy of Pediatrics currently recommends that all infant discharge policies include parent edu-cation on CSS installation, regular review of educa-tional materials, and periodic in-service education for responsible staff.29Pediatric clinics and practices

represent another excellent opportunity for deliver-ing personal messages to the target audience, and hands-on instruction has been shown to decrease the numbers of errors in CSS installation.5 Information

on available training opportunities throughout the United States is available from NHTSA through its web site at www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/ childps/Training/index.html or via a hotline at 1– 800-424 –9393.

Engineering improvements may indeed prove to be the most important factor in decreasing misuse. Uniform standards such as upper tether straps and lower anchorage systems (which allow seats virtu-ally to be snapped in place) have the potential to make CSS installation a much simpler process, re-quiring very little instruction.

With respect to our testing methods, it needs to be noted that there are limitations inherent in the SMOG readability test. Many common words such as “vehicle,” “serious,” and “injury” were repeated

often in virtually all of the instruction sets. Although some may argue that these 3-syllable words may be easily understood, testing procedures called for them to be counted in the SMOG tally. This most likely increased the overall grade level of the samples. However, it is doubtful that these words alone could account for a doubling of the sample’s reading level in comparison to what experts recommend.

Also, the SMOG score instructions specifically stated that hyphenated words count as 1 word. This is worth noting, because some manufacturers hy-phenated the words “rear-facing” and “forward-fac-ing,” whereas others did not. This difference may have affected comparisons among manufacturers but would not explain the sample’s high mean readabil-ity level overall.

We achieved a high degree of interrater reliability when applying the SMOG testing method to our study sample ( ⫽0.80). As noted in previous liter-ature, a exceeding 0.6 is considered to reflect a good level of agreement.30 Also, the test’s outcome

did not seem to be overly sensitive to brand or model names.

Finally, this study also suggests some areas for potential future research. It would be valuable, for example, to evaluate the effectiveness of installation instruction sets. This could be done by taking people with no previous experience with CSSs, giving them instruction manuals, and noting the success rate of installation. A small-scale study of this type has al-ready been performed in Canada31; however, it may

be beneficial to repeat this work on a larger scale. It would also be of interest to determine whether an association exists between literacy and proper CSS installation and use and whether misuse patterns are associated with the readability of instruction sets.

Still, it seems advisable from our data that manu-facturers of CSS rewrite their instruction sets to a fifth-grade reading level. This could be accomplished by using shorter sentences and simpler words. For example, “collision,” “automobile,” and “remedied” could be replaced by “crash,” “car,” and “fixed.” Subsequent testing could verify whether the desired level of clarity had been achieved. The NHTSA has announced that they will consider mandating a mimum reading level for CSS labels and written in-structions after conducting more research.32

Manu-facturers and regulators may also want to explore whether alternatives to written installation instruc-tions should be made available to consumers. If the above recommendations are put into practice in the short term and design improvements are widely adopted in the long-term, then the prevalence of proper CSS use may increase to a level befitting the importance of this effective injury prevention tool.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Susanne Ogaitis-Jones and Julia Alkire for sharing expertise on CSS, David Cruess for guidance on statistical analyses, and the NHTSA for making CSS instruction collection available and for providing valuable background information on this topic. Julianne J. Brown acted as our second rater of CSS instructions.

REFERENCES

1. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Vital Statistics System.

National Mortality Data, 1998. Hyattsville, MD: NCHS; 2000

2. Johnston C, Rivara FP, Soderberg R. Children in car crashes: analysis of data for injury and use of restraints.Pediatrics.1994;93:960 –965 3. Kahane C.An Evaluation of Child Passenger Safety: The Effectiveness and

Benefits of Safety Seats. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 1986

4. Decina LE, Knoebel KY. Child safety seat misuse patterns in four states.

Accid Anal Prev.1997;29:125–132

5. Lane WG, Liu GC, Newlin E. The association between hands-on instruc-tion and proper child safety seat installainstruc-tion. Pediatrics. 2000;106: 924 –929

6. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.Observed Patterns of Misuse of Child Safety Seats. Traffic Tech, Sept 1996. Washington, DC: NHTSA; 1996

7. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Uniform child re-straint anchorages. Available at: www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/ childps/ucra/index.html. Accessed March 12, 2001

8. Conrath DC, Doak LG, Root JH.Teaching Patients With Low Literacy Skills.2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott; 1996

9.National Adult Literacy Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 1992

10. Hletko PJ, Hletko JD, Shelness AM, Robin SS. Demographic predictors of infant car seat use.Am J Dis Child.1983;137:1061–1063

11. Weiss BD, Coyne C. Communicating with patients who cannot read.

N Engl J Med.1997;337:272–274

12. Morrow GR. How readable are subject consent forms?JAMA.1980;244: 56 –58

13. Powers RD. Emergency department patient literacy and the readability of patient-directed materials.Ann Emerg Med.1988;17:124 –126 14. Davis TC, Mayeaux EJ, Fredrickson D, Bocchini JA Jr, Jackson RH,

Murphy PW. Reading ability of parents compared with reading level of pediatric patient education materials.Pediatrics.1994;93:460 – 468 15. Wells JA. Readability of HIV/AIDS educational materials: the role of

the medium of communication, target audience, and producer charac-teristics.Patient Educ Couns.1994;24:249 –259

16. Williams MV, Parker RM, Baker DW, et al. Inadequate functional health literacy among patients at two public hospitals. JAMA. 1995;274: 1677–1682

17. Powell EC, Tanz RR, Uyeda A, Gaffney MB, Sheehan KM. Injury prevention education using pictorial information.Pediatrics.2000;105(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/105/1/e16 18. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Manufacturers’

In-structions for Child Safety Seats, 1999 Edition CD-ROM. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2000

19. American Academy of Pediatrics. 2000 Family Shopping Guide to Car Seats: Safety and Product Information from the American Academy of Pediatrics. Available at: www.aap.org/family/famshop.htm. Accessed March 14, 2001

20. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. List of Child Safety Seat Manufactures. Available at: www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/ childps/csr2001/csrhtml/csManufacturers.html. Accessed May 8, 2001 21. SafetyBeltSafe, U.S.A. List of Child Restraints by Manufacturer.

Avail-able at: www.carseat.org. Accessed March 14, 2001

22. Epinions.com. Reviews of Car Seats. Available at: www.epinions.com/ kifm-Baby_Equipment-Car_Seats-All/_redir_att_⬃1. Accessed May 30, 2001

23. McLaughlin GH. SMOG-grading—new readability formula. J Read.

1969;12:639 – 646

24. National Cancer Institute.Making Health Communication Programs Work. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1989 (NIH Publ. No. 89-1493)

25. Child Restraint Systems, 49 C.F.R. §571.213; 2000 26. SPSS. Release 10.0.5. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc; 1999

27. Microsoft Excel 2000. Redmond, WA: Microsoft Corporation; 1999 28. Federal Register. 66(213):55623–55633; November 2, 2001

29. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. Safe transportation of newborns at hospital discharge. Pe-diatrics.1999;104:986 –987

30. Altman, DG.Practical Statistics for Medical Research.London, United Kingdom: Chapman and Hall; 1991

31. Noy YI, Arnold A-K.Installing Child Restraint Systems in Vehicles: Toward Usability Criteria. Montreal, Quebec: Transport Canada; 1995 (Technical Memorandum TME 9501)

32. Federal Register. 67(190):61523– 61531; October 1, 2002

ARTICLES 591

at Viet Nam:AAP Sponsored on August 30, 2020 www.aappublications.org/news

DOI: 10.1542/peds.111.3.588

2003;111;588

Pediatrics

Mark V. Wegner and Deborah C. Girasek

How Readable Are Child Safety Seat Installation Instructions?

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/111/3/588 including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/111/3/588#BIBL This article cites 12 articles, 3 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/carseat_safety_sub Carseat Safety

son_prevention_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/injury_violence_-_poi Injury, Violence & Poison Prevention

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

DOI: 10.1542/peds.111.3.588

2003;111;588

Pediatrics

Mark V. Wegner and Deborah C. Girasek

How Readable Are Child Safety Seat Installation Instructions?

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/111/3/588

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.

the American Academy of Pediatrics, 345 Park Avenue, Itasca, Illinois, 60143. Copyright © 2003 has been published continuously since 1948. Pediatrics is owned, published, and trademarked by Pediatrics is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly publication, it

at Viet Nam:AAP Sponsored on August 30, 2020 www.aappublications.org/news