R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E

Open Access

Factors associated with institutional delivery in

Ghana: the role of decision-making autonomy

and community norms

Ilene S Speizer

1,2*, William T Story

1and Kavita Singh

1,2Abstract

Background:In Ghana, the site of this study, the maternal mortality ratio and under-five mortality rate remain high indicating the need to focus on maternal and child health programming. Ghana has high use of antenatal care (95%) but sub-optimum levels of institutional delivery (about 57%). Numerous barriers to institutional delivery exist including financial, physical, cognitive, organizational, and psychological and social. This study examines the psychological and social barriers to institutional delivery, namely women’s decision-making autonomy and their perceptions about social support for institutional delivery in their community.

Methods:This study uses cross-sectional data collected for the evaluation of the Maternal and Newborn Referrals Project of Project Fives Alive in Northern and Central districts of Ghana. In 2012 and 2013, a total of 2,527 women aged 15 to 49 were surveyed at baseline and midterm (half in 2012 and half in 2013). The analysis sample of 1,606 includes all women who had a birth three years prior to the survey date and who had no missing data. To determine the relationship between institutional delivery and the two key social barriers—women’s decision-making autonomy and community perceptions of institutional delivery—we used multi-level logistic regression models, including cross-level interactions between community-level attitudes and individual-level autonomy. All analyses control for the clustered survey design by including robust standard errors in Stata 13 statistical software.

Results:The findings show that women who are more autonomous and who perceive positive attitudes toward facility delivery (among women, men and mothers-in-law) were more likely to deliver in a facility. Moreover, the interactions between autonomy and community-level perceptions of institutional delivery among men and mothers-in-law were significant, such that the effect of decision-making autonomy is more important for women who live in communities that are less supportive of institutional delivery compared to communities that are more supportive.

Conclusions:This study builds upon prior work by using indicators that provide a more direct assessment of perceived community norms and women’s decision-making autonomy. The findings lead to programmatic recommendations that go beyond individuals and engaging the broader network of people (husbands and mothers-in-law) that influence delivery behaviors.

Keywords:Institutional delivery, Ghana, Maternal health, Autonomy, Social support

* Correspondence:Ilene_speizer@unc.edu

1Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

2Department of Maternal and Child Health, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Background

As we approach 2015 and the deadline for attainment of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG), increased attention and effort are being given to reaching target populations with specific programmatic strategies, espe-cially in countries that are not on track to attain the MDGs. In Ghana, the site of this study, where the ma-ternal mortality ratio (MMR) remains high at 350 mater-nal deaths per 100,000 live births [1] and under-five mortality is estimated at 82 deaths per 1000 live births [2], there has been increased attention to initiatives to improve maternal, infant, and child health services. To help in the attainment of improved infant and child health (MDG 4) and improved maternal health (MDG 5), programs in Ghana and elsewhere promote skilled at-tendance at delivery; in many low income countries, this is equated with institutional (also called facility) delivery [3]. Skilled attendance at delivery means having an accredited health professional, including a midwife, doc-tor, or nurse, who has been trained in the skills needed to manage a normal or uncomplicated pregnancy and childbirth and to support the woman in the immediate postpartum period. This person should also be able to identify, manage and refer complications experienced by the woman or the newborn [4].

Numerous studies have demonstrated that in sub-Saharan Africa, including Ghana, there is often high use of antenatal care services but lower use of institutional delivery [2,5,6]. For example, the 2008 Ghana Demo-graphic and Health Survey (GDHS) showed that more than 95% of women who had a birth in the last five years received antenatal care from a skilled provider prior to birth [6]. As compared to high antenatal care use, only 57% of women had an institutional delivery and only 59% delivered with a skilled attendant present [6]; simi-lar distinctions are found in the 2011 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey [2]. Wide variability in institutional deliv-ery and skilled attendance at delivdeliv-ery was observed by region of residence with the Northern region having the lowest percentage of women delivering in a facility and the Central region falling in the middle on percentage of births in a facility [6]; these are the two regions covered in this study.

A number of studies using the GDHS demonstrated important demographic- and policy-level factors associ-ated with institutional delivery [7-9]. Recent global stud-ies have examined common barriers to antenatal care and institutional delivery [3,10-17]. Much of this re-search has focused on transportation, distance, and cost [13,15,16]. A recent qualitative study by Matsuoka and colleagues in Cambodia (2010) demonstrated five types of barriers to utilization of government maternal health services [17]. These barriers were: financial; physical; cognitive; organizational; and psychological and social.

Often, the financial and physical barriers are examined together to capture issues around transportation and distance to a facility as well as costs to reach or use the facility [13,15-17]. Ghana has implemented the National Health Insurance Scheme in an effort to reduce these types of financial barriers. Recent studies from Ghana have found that women with health insurance were more likely to have an institutional delivery [18-20] and insurance was associated with better maternal and child health outcomes [20]. Cognitive barriers are related to misconceptions about services offered and concerns about quality of services [17]. Organizational barriers are focused on the role of the providers in terms of atti-tudes, availability, and services offered [17,21]; these have been found to be particularly important from quali-tative studies in Ghana [14,21]. Finally, psychological and social barriers are related to community norms and attitudes toward facility delivery and toward the staff at the facility [3,17]. These barriers to health care have been demonstrated in various cultural contexts including Bangladesh [22], Cambodia [17], Nepal [23], rural Kenya [13], and Northern Ghana [10] mostly using qualitative data or nationally representative data from Demographic and Health Surveys.

Social barriers to institutional delivery, such as com-munity attitudes towards institutional delivery and levels of decision-making autonomy among women, have re-ceived much less attention in the literature [24]. Com-munity beliefs and attitudes about maternal health behaviors have been shown to influence a woman’s indi-vidual decision to seek care. For example, in a study of six countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Stephenson and col-leagues [25] found that community norms about facility-based delivery and women’s decision-making autonomy were potential pathways that influenced the decision to deliver a child in a health facility. In rural Tanzania, com-munity beliefs that facility delivery is important for the health of the mother and baby were associated with use of facility-based delivery [26]. In a separate study among the same population in Tanzania, male partners’ opinions about institutional delivery were associated with actual in-stitutional delivery, such that spouses who disagreed about the importance of institutional delivery were less likely to have one compared to spouses who agreed that delivering in a health facility was important [27]. In rural Mali, mothers-in-law’s beliefs and attitudes were demonstrated to have an influence on their daughters-in-law’s maternal health care-seeking behaviors [28].

health facility for childbirth [29]. In Bangladesh, house-holds in which husbands made decisions alone were asso-ciated with less use of antenatal care and skilled delivery care compared to households that practiced joint decision-making [30]. The relationship between women’s decision-making autonomy and use of maternal health services may be due to women’s power to realize their preferences, which includes a stronger preference for ensuring their own health [31]. Although some studies have demon-strated the importance of community norms and women’s decision-making autonomy on the decision to deliver in a health facility, there have been few studies that have looked at the two pathways together and examined the ways in which community norms and household decision-making autonomy interact with one another.

This study contributes to our understanding of auton-omy and social barriers to institutional delivery in Ghana using recently collected quantitative data from two re-gions of Ghana. Because the focus of the study was to obtain information on barriers to institutional delivery and women’s referral experiences, this study includes a large sample of women who recently delivered a child, providing rich information on barriers to institutional delivery in these regions. The objectives of this study are to examine whether women’s decision-making roles and their perceptions about social support for facility deliv-ery, measured at the individual and community levels, are associated with women’s actual place of delivery in Ghana. Furthermore, we examine how the relationship between community-level attitudes and institutional de-livery differs for households in which women have a say in their own health care and those that do not.

Methods

Data collection

The cross-sectional data for this study come from base-line and midbase-line surveys that were used during the evaluation of the Maternal and Newborn Referrals Pro-ject of ProPro-ject Fives Alive in the Northern and Central Regions of Ghana. The Maternal and Newborn Referrals project is being implemented by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), the National Catholic Health Service (NCHS) and the Ghana Health Service (GHS). The evalu-ation is being led by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the University of Ghana. Baseline data were collected between May and June 2012 to help design the project and midline data were collected between October and November 2013 to help strengthen project implemen-tation. Since the focus of this study is not significantly affected by the interventions implemented as part of the Maternal and Newborn Referrals Project and there were delays in project initiation until July, 2013, the baseline and midline data were merged to provide a lar-ger cross-sectional sample.

Multiple survey instruments were used at baseline and midline, including a household survey, a community leader survey, and facility surveys (with clients, providers, trad-itional birth attendants, and chemical sellers). This analysis focuses on the household survey data. The purpose of the household survey was to obtain information on knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding maternal and child health services.

The household survey used the 30-by-N cluster sam-ple design; this method is commonly used in child sur-vival programs [25,32]. Cluster sampling is an efficient sampling method because it provides a means to obtain a representative sample from the region without under-taking a census of households in the community. How-ever, cluster sampling leads to biased standard errors due to the correlation between observations from the same cluster. We explain our approach for accounting for the biased standard errors in the analysis section. The overall sampling strategy was designed to meet the evaluation objectives for the Maternal and Newborn Re-ferrals Project [18]. At baseline, the goal was to include a large sample of recently pregnant women (pregnant in the last 12 months) to identify their experiences with pregnancy, childbirth, and newborn health. Thus, we used a 30-by-7 sampling approach to identify thirty clus-ters per region (thirty from the three districts in the Northern region and thirty from the three districts in the Central region), and seven recently pregnant women in each cluster were randomly selected for interview. Random selection of clusters was undertaken from an exhaustive list of communities in the six study districts. The recently pregnant women were randomly sampled from a list of all recently pregnant women in the com-munity (determined through interviews with comcom-munity leaders and health workers in the community). To sup-plement the sample of 210 recently pregnant women per region, we also included 14 nearby neighbor women (ages 15–49) who may or may not have been recently pregnant to permit an examination of maternal and newborn health knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of women in the community. At midline, the same 30-by-N cluster design was employed, however, a new sample of communities was drawn from the same districts. As with the baseline survey, in all selected clusters, seven recently pregnant women were surveyed as well as 14 nearby neighbors.

on a sub-sample of the 2,527 women interviewed, which excludes women who did not have a birth in the last three years, were not in union, or had missing informa-tion on the key variables of interest. Thus the final ana-lysis sample is 1,606 women.

Ethics review approval for the study was obtained by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the Ghana Health Service. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Variables

The key dependent variable for this analysis is the place of delivery of the last birth in the last three years. Women who delivered in a health facility are coded one, whereas all women who delivered at home or in the home of some-one else (e.g., a relative or a health worker) are coded zero (i.e., non-institutional delivery).

The main independent variables for this analysis focus on decision-making autonomy and attitudes toward in-stitutional delivery. First, all women were asked: “Who usually makes decisions about health care for you?” Women who reported that they make the decisions alone or make the decisions jointly with their partner were the reference group (high decision-making auton-omy), and were compared to women who reported that their partner makes the decision alone (low decision-making autonomy). A third category was also created for the small number of women who reported that someone else makes the decision. The other independent variables of interest are attitudes toward institutional delivery, represented by three separate questions. First, all women were asked: “How many women do you think in your community deliver their baby in a health facility?” Re-sponse options were: none, some, most, and all (coded 1–4); the small number of women who reported “don’t know”(n = 114) were dropped from the analysis. Second, women were asked: “In your opinion, what percentage of men in your community is supportive of facility deliv-ery?” Response options were: no men, few men, some men, most men, and all men (coded 1–5); the 149 women who reported “don’t know” were dropped from the analysis. Finally women were asked: “In your opin-ion, what percentage of mothers-in-law in your commu-nity is supportive of facility delivery?” Response options were: no mothers-in-law, some mothers-in-law, most mothers-in-law, and all mothers-in-law (coded 1–4); the 172 women who reported “don’t know” were dropped from the analysis.

To examine community-level attitudes toward facility delivery, we also created comparable variables at the community-level for each of the three attitude questions. In particular, for each woman, we calculated the average response on how many women in the community she perceived had delivered their baby in a health facility.

These community-level responses were calculated by cre-ating an average value of all women living in the cluster, removing each individual woman from the calculation. A similar approach was undertaken for the community-level men’s attitude and the community-level mother-in-law’s attitude.

All models control for demographic factors previously found to be associated with facility delivery including age, education, ethnicity, employment status, religion, parity, wealth, region, and time period (baseline or mid-line) [24]. See Table 1 for a description of these variables. The wealth variable was created based on three house-hold characteristics: type of toilet, type of fuel used in the household, and location of the kitchen. Households with a non-improved toilet facility (as defined in the Ghana DHS), that use wood for their source of fuel, and that have a kitchen outside their household were coded as being the poorest households. Households with two out of three of these lower quality scenarios were considered to be medium, and households with none or just one of these lower quality scenarios were considered to be the richest. This is the same approach that was used in an earlier ana-lysis of health insurance effects on facility delivery using these same data [18]. In the full sample, based on this clas-sification, about 40% of the women were in the poorest category, 40% in the medium category, and only 19% were in the richest category (see Table 1). It is worth noting that use of antenatal care (ANC) during the pregnancy was not included as an independent variable in the reduced form models presented. Previous research has demonstrated that use of ANC is endogenous and would introduce bias into the models presented [33].

Analysis

Table 1 Characteristics of total sample (baseline and midline), recent birth sample, and analysis sample from Ghana evaluation of Maternal and Newborn Referrals Project, 2012, 2013

Characteristics Full sample Recent birth sample (birth in the last 3 years)

Analysis sample (in union, birth in the last 3 years, no missing information)

Percent Number (n = 2527*) Percent Number (n = 1840*) Percent Number (n = 1606)

Age:

<19 7.8 196 7.5 138 4.7 76

20-24 23.7 597 25.4 468 23.4 375

25-34 44.7 1,127 48.7 896 51.9 833

35-49 23.9 604 18.4 338 20.1 322

Education:

None 47.4 1,199 45.3 835 50.0 803

Primary 20.1 508 20.5 378 18.4 295

Secondary or higher 32.4 819 34.2 629 31.6 508

Ethnicity:

Akan 47.9 1,210 50.3 926 45.6 732

Mole-Dagbani 32.1 811 30.8 568 34.5 554

Konkomba 9.6 242 8.9 164 9.3 150

Other 10.4 264 10.0 184 10.6 170

Work status:

Unpaid/unemployed 58.3 1,474 59.3 1,092 57.7 927

Self employed 38.1 964 37.1 684 38.7 622

Paid work 3.5 89 3.6 66 3.6 57

Religion:

Christian 56.0 1,414 58.1 1,071 54.4 874

Muslim 29.8 752 28.1 517 30.7 493

None/traditional/other 14.3 361 13.8 254 14.9 239

Marital status:

Not currently in union 15.1 381 12.7 234 0.0 0

Currently in union 84.9 2,146 87.3 1,608 100.0 1606

Parity:

0 4.9 124 0.0 0 0 0

1 20.8 526 23.2 427 18.4 296

2 15.7 397 17.9 329 17.3 277

3 14.0 352 14.9 275 16.2 260

4 12.7 322 13.1 242 14.2 228

5 9.6 242 9.9 183 10.9 175

6+ 22.3 564 21.0 386 23.0 370

Region:

Central 50.1 1,267 52.6 968 48.0 770

Northern 49.9 1,260 47.5 874 52.1 836

Wealth category

Poorest 40.4 1,022 40.5 745 41.5 667

Medium 40.3 1,019 40.3 742 39.3 631

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics of three sample populations: the full sample (n = 2,527), the sam-ple of women who had a recent birth (n = 1,840), and the final analysis sample of women in union who had a recent birth and had non-missing information on all study variables (n = 1,606). Women who were not in union were dropped from the analysis since one of the key independent variables on autonomy was specifically about decision-making in union. The only difference ob-served between the full sample and the final analysis sample is that the analysis sample is made up of a greater percentage of women from the midline sample. At midline, the study recruited a greater number of re-cently pregnant women in the neighbor sample, increas-ing the proportion of the sample from midline in the recently pregnant sample. More than two-fifths of the women surveyed for this study are uneducated, and more than two-fifths are of Akan and one-third is of Mole-Dagbani ethnicity. More than half of the women are unemployed or doing unpaid work. More than half of the sample is Christian, and a little less than a third is Muslim. In the analysis sample, all women have had at least one birth (since the outcome is place of delivery of the last birth) with about equal proportions having one, two, or three births. Twenty-three percent of the women have had six or more births. Finally, the full sample is evenly divided between the Central and Northern re-gions, whereas the analysis sample includes a greater percentage of women from the Northern region; this may be suggestive of more pregnancies among women in union in the Northern region. To assess if differences be-tween the baseline and midline samples are influencing the results, we re-ran the regression analyses with only the baseline sample; the results were similar for the key inde-pendent variables of interest (results not shown).

Table 2 presents the distribution of the key independ-ent variables (perceptions about facility delivery and decision-making autonomy) in the analysis sample and then by whether or not the woman had a facility deliv-ery. First, women’s attitudes toward how many women deliver in a health facility indicate that more than half of women report that most women deliver in a health facil-ity (52%), and another 13% report that all women deliver in a facility. About 35% of women report none or some women deliver in a facility. Second, women’s perceptions

of men’s opinions of facility delivery indicate that the majority of women (about 70%) believe that most men or all men are supportive of facility delivery. About 30% of women report that no men, few men and some men are supportive of facility delivery. Third, women’s per-ceptions of mothers-in-law’s opinions are similar to women’s perceptions of men’s opinions of facility deliv-ery. Fourth, about half of the women report that they alone, or with their partner, make decisions about their own health care. Forty-seven percent of women report that their husband alone makes these health care deci-sions and only 4% report that someone else makes these decisions. When comparing the attitude and autonomy variables by whether or not the woman had a facility de-livery, a significant difference is found in the expected direction, such that those women who had a facility de-livery have attitudes that are more supportive of facility delivery than those women who did not have a facility delivery.

Table 3 presents the odds ratios and 95% confidence in-tervals for the analysis of having a facility delivery com-pared to not having a facility delivery among women in union who had a birth in the last three years. The key vari-ables of interest to this analysis are at the bottom of the table. Note that because of high correlation between the attitude variables (e.g., attitudes about facility delivery for all women, attitudes about men’s support for facility deliv-ery and attitudes about mother-in-law’s support for facility delivery), models were run separately for each of these in-dependent variables.

Model 1 demonstrates that women who perceive that a greater number of women in their community deliver in a facility are significantly more likely to have delivered their last birth in a facility (OR: 1.83; 95% CI: 1.53-2.19) compared to women who think fewer women deliver in a facility. Furthermore, women who report that someone other than herself or her spouse makes decisions about her own health care were more likely to deliver in a fa-cility (OR: 2.22; 95% CI: 1.09-4.53) compared to women who are involved in the decision-making process. This variable is not significant in the other models and may merit consideration in future analyses. Community-level attitude toward facility delivery is also significant in Model 1 indicating that, controlling for the woman’s own attitude toward the number of women who deliver in a fa-cility, women who live in communities where more women Table 1 Characteristics of total sample (baseline and midline), recent birth sample, and analysis sample from Ghana evaluation of Maternal and Newborn Referrals Project, 2012, 2013(Continued)

Time

Baseline 50.1 1,267 45.7 841 45.8 735

Midline 49.9 1,260 54.3 1011 54.2 871

perceive higher use of facility delivery are more likely to de-liver in a facility than women who live in communities where women perceive fewer facility deliveries (OR: 4.13; 95% CI: 2.49-6.85). The patterns for the key variables of interest remained the same in Model 2 and there was no significant interaction between decision-making autonomy and community-level attitudes.

Models 3 and 4 tell a slightly different story. In Model 3, women who perceive that more men are supportive of facility delivery are significantly more likely to deliver in a facility (OR: 1.36; 95% CI: 1.18-1.55). In addition, women who report that the husband alone makes deci-sions about her health care are significantly less likely to have a facility delivery than women who report that she is involved in decision-making (OR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.58-0.96). Model 3 also shows that controlling for women’s own attitudes toward men’s support for facility delivery, women who live in communities where men are per-ceived to have more positive attitudes are significantly

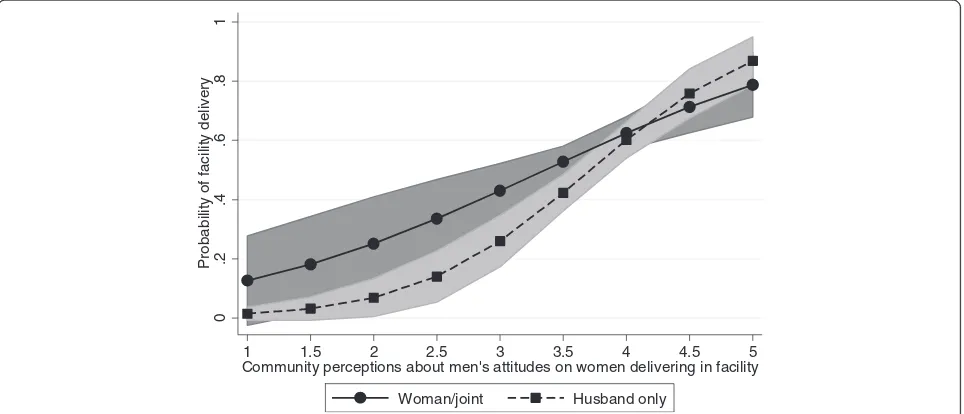

more likely to have a facility delivery than all others (OR: 3.70; 95% CI: 2.27-6.05). Model 4, which adds an interaction term between women’s decision-making au-tonomy and men’s community-level attitudes, shows that the effect of the husband making the decision alone be-comes more important (and remains negative), particu-larly for women with less male support for facility delivery at the community-level (OR: 0.04; 95% CI: 0.01-0.32). The interaction, depicted in Figure 1, shows that when husbands make decisions alone and community attitudes toward men’s support are low, the predicated probability of facility delivery is low. Conversely, when community attitudes toward men’s support are high, whether the husbands make decisions alone or not, the probability of facility delivery is higher and more similar to when the wife is involved in health care decisions.

Finally, Models 5 and 6 provide similar findings. Spe-cifically, Model 5 shows that women who perceive that more mothers-in-law are supportive of facility delivery Table 2 Attitudes toward facility delivery and who makes decisions in the household and distribution by whether the woman had a facility delivery in Ghana 2012, 2013

Characteristics Analysis sample

(in union with recent birth)*

Distribution by whether had a facility delivery for last birth

Percent Number Non-facility delivery (47.0%)

Facility delivery (53.0%)

How many women do you think in your community deliver their baby in a health facility?

None 5.7 87 10.7 1.3

Some 29.1 446 40.1 19.7

Most 52.4 803 43.4 60.1

All 12.9 197 5.8 18.9***

In your opinion, what percentage of men in your community are supportive of facility delivery?

No men 1.9 29 4.0 0.1

Few men 11.5 174 17.7 6.2

Some men 17.0 257 20.8 13.7

Most men 52.8 797 46.9 57.9

All men 16.8 253 10.6 22.1***

In your opinion, what percentage of mother-in-laws in your community are supportive of facility delivery?

No mothers-in-law 3.9 59 7.6 0.8

Some mothers-in-law 29.8 446 37.4 23.2

Most mothers-in-law 51.2 767 44.0 57.4

All mothers-in-law 15.1 227 11.1 18.7***

Who usually makes decisions about health care for you:

Woman alone/both partners 49.3 791 39.9 57.5

Husband only 46.6 748 57.7 36.7

Other 4.2 67 2.4 5.8***

Table 3 Logistic regression odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of association between attitudes and decision-making autonomy and whether a woman delivered a recent birth in a facility, Ghana, 2012, 2013 Characteristics Facility delivery

vs. non-facility delivery

Facility delivery vs. non-facility delivery

Facility delivery vs. non-facility delivery

Facility delivery vs. non-facility delivery

Facility delivery vs. non-facility delivery

Facility delivery vs. non-facility delivery

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 Model 6

Time

Baseline 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0

Midline 1.20 (0.80-1.81) 1.21 (0.81-1.81) 0.83 (0.56-1.25) 0.85 (0.57-1.27) 0.84 (0.55-1.28) 0.86 (0.56-1.32)

Age:

<25 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0

25-34 1.00 (0.71-1.39) 1.00 (0.71-1.40) 1.06 (0.77-1.46) 1.07 (0.77-1.47) 1.00 (0.73-1.37) 1.00 (0.73-1.38)

35-49 1.17 (0.74-1.85) 1.18 (0.74-1.86) 1.24 (0.79-1.93) 1.26 (0.81-1.98) 1.13 (0.75-1.71) 1.15 (0.76-1.74)

Education:

None 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0

Primary 1.40 (0.94-2.09)+ 1.41 (0.94-2.10)+ 1.31 (0.92-1.88) 1.32 (0.92-1.90) 1.43 (1.01-2.03)* 1.45 (1.02-2.07)*

Secondary or higher 1.92 (1.27-2.92)** 1.93 (1.27-2.92)** 2.04 (1.40-2.96)*** 2.06 (1.42-2.99)*** 2.21 (1.52-3.23)*** 2.26 (1.55-3.30)***

Ethnicity:

Akan 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0

Mole-Dagbani 1.43 (0.43-4.84) 1.40 (0.41-4.72) 1.25 (0.34-4.61) 1.15 (0.32-4.20) 1.51 (0.45-5.09) 1.47 (0.44-4.93)

Konkomba 5.31 (1.69-16.69)** 5.43 (1.74-16.96)** 3.25 (0.97-10.88)+ 3.33 (1.01-10.95)* 2.34 (0.74-7.36) 2.40 (0.77-7.46)

Other 1.45 (0.60-3.51) 1.45 (0.60-3.48) 1.35 (0.56-3.27) 1.30 (0.55-3.12) 1.49 (0.67-3.31) 1.46 (0.66-3.24)

Work status:

Unpaid/unemployed 0.75 (0.57-1.00)+ 0.76 (0.57-1.01)+ 0.80 (0.61-1.06) 0.81 (0.62-1.07) 0.72 (0.55-0.95)* 0.73 (0.56-0.96)*

Self-employed/paid work 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0

Religion:

Christian 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0

Muslim 1.34 (0.67-2.66) 1.33 (0.67-2.63) 1.25 (0.57-2.77) 1.23 (0.57-2.70) 1.25 (0.58-2.72) 1.23 (0.57-2.64)

None/traditional/other 0.53 (0.33-0.86)** 0.53 (0.33-0.86)** 0.50 (0.30-0.83)** 0.51 (0.31-0.84)** 0.47 (0.30-0.75)** 0.47 (0.29-0.75)***

Parity (continuous): 0.95 (0.92-0.98)** 0.95 (0.92-0.98)** 0.95 (0.92-0.98)** 0.95 (0.92-0.98)** 0.96 (0.93-0.99)** 0.96 (0.93-0.99)**

Region:

Central 2.83 (0.96-8.33)+ 2.73 (0.92-8.09)+ 1.98 (0.62-6.39) 1.84 (0.57-5.93) 2.15 (0.72-6.44) 2.06 (0.68-6.23)

Northern 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0

Wealth category

Poorest 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0

Medium 1.30 (0.99-1.72)+ 1.30 (0.98-1.72)+ 1.24 (0.93-1.63) 1.21 (0.91-1.61) 1.28 (0.97-1.68)+ 1.26 (0.96-1.67)

Richest 1.93 (1.32-2.82)*** 1.93 (1.32-2.83)*** 1.87 (1.25-2.81)** 1.87 (1.24-2.81)** 1.94 (1.29-2.90)*** 1.95 (1.30-2.92)***

Decision-making about woman’s healthcare

Woman/joint decision-making

1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0

Husband alone 0.81 (0.63-1.05) 0.37 (0.07-1.99) 0.74 (0.58-0.96)* 0.04 (0.01-0.32)** 0.73 (0.57-0.94)* 0.08 (0.01-0.50)**

Other 2.22 (1.09-4.53)* 5.73 (0.14-227.93) 1.65 (0.82-3.31) 0.41 (0.01-23.09) 1.77 (0.83-3.76) 1.11 (0.03-42.74)

Perceived number of women that delivery in facility

are more likely to deliver in a facility and women with low decision-making autonomy are less likely to deliver in a fa-cility. Furthermore, controlling for women’s own attitudes toward mothers-in-law’s support for facility delivery, women living in communities where there is greater per-ceived support for facility delivery by mothers-in-law are more likely to deliver in a facility than all others (OR: 3.46; 95% CI: 1.85-6.45). Model 6 includes the interaction be-tween women’s decision-making autonomy and

mother-in-law’s community-level attitudes. The interaction, depic-ted in Figure 2, demonstrates that women who have low decision-making autonomy (husbands make decisions alone) have a lower predicted probability of a facility deliv-ery when community attitudes toward mothers-in-law’s support for facility delivery are low. When community attitudes toward mothers-in-law’s support are higher, the effect of lower decision-making autonomy is more similar to when women have higher decision-making autonomy. Table 3 Logistic regression odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of association between attitudes and

decision-making autonomy and whether a woman delivered a recent birth in a facility, Ghana, 2012, 2013(Continued)

Perception of men’s attitude toward facility delivery

Na Na 1.36 (1.18-1.55)*** 1.36 (1.19-1.56)*** Na Na

Perception of MIL attitude toward facility delivery

Na Na Na Na 1.40 (1.18-1.65)*** 1.41 (1.19-1.66)***

Community attitudes

Attitudes toward number that delivery in facility

4.13 (2.49-6.85)*** 3.62 (2.02-6.51)*** Na Na Na Na

Men’s attitudes toward facility delivery

Na Na 3.70 (2.27-6.05)*** 2.48 (1.47-4.19)*** Na Na

MIL attitudes toward facility delivery

Na Na Na Na 3.46 (1.85-6.45)*** 2.20 (1.11-4.34)*

Interactions

Community attitude *Husband alone decides

Na 1.33 (0.72-2.45) Na 2.14 (1.26-3.62)** Na 2.25 (1.15-4.42)*

Community attitude *Other decide

Na 0.70 (0.19-2.59) Na 1.45 (0.50-4.22) Na 1.18 (0.30-4.62)

Na–not applicable for that model. Sample size slightly smaller than full sample since small number of missing observations were dropped for perception questions by model.

+p≤0.10; *p≤0.05; **p≤0.01; ***p≤0.001.

0

.2

.4

.6

.8

1

P

rob

ab

ilit

y

o

f

fa

c

ili

ty

d

e

liv

e

ry

1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 4 4.5 5

Community perceptions about men's attitudes on women delivering in facility

Woman/joint Husband only

Discussion

Using these unique data, we find that supportive community-level attitudes are associated with greater odds of facility delivery, even after controlling for a woman’s own perceptions about community attitudes. In addition, women with lower decision-making autonomy regarding their own health care have lower odds of facility delivery compared to women who are involved in health care deci-sions. In models that include community-level attitudes about men’s and mothers-in-law’s support for facility de-livery, the interaction between autonomy and community attitudes is significant indicating that women with low decision-making autonomy who also live in communities that are less supportive of facility delivery are the least likely to have a facility delivery. Conversely, women who have low decision-making autonomy who live in commu-nities that are more supportive of facility delivery are more similar to women with high decision-making autonomy. Therefore, perceived men’s and mothers-in-law’s commu-nity attitudes are influential, even for the least empowered women.

Previous studies have also demonstrated that there are psychological and social barriers to maternal and child health services [3,10,17]. These studies have generally fo-cused on qualitative data whereas our study uses quantita-tive data to demonstrate similar influences. Our findings are consistent with other studies from Ghana that used Demographic and Health Survey data in terms of demo-graphic characteristics associated with facility delivery [7,8]. However, our study is unique because of its focus on maternal and child health care utilization with specific questions on attitudes toward facility delivery at multiple

levels (including perceived attitudes of husband’s and mothers-in-law).

Our findings corroborated findings from two previous studies that have shown that support for facility deliver-ies by mothers-in-law and husbands is associated with institutional delivery [27,28]. White and colleagues [28] found similar results in that women in rural Mali whose mothers-in-law agreed with traditional and cultural practices were less likely to deliver in a health facility. The traditional views of mothers-in-law may contradict more contemporary views of pregnancy and childbirth. Contrary to our results, rural Malian women’s own per-ceptions of delivery practices of women in the commu-nity, and the perceptions of their husbands, were not associated with place of delivery. Furthermore, Danforth and colleagues [27] found that spousal agreement about the place of delivery was associated with facility delivery in rural Tanzania. This evidence supports our notion that the opinions of both partners are important when deciding where to deliver their child.

Previous studies that have explored community-level attitudes about facility delivery did not have the same amount of detail that our study provides. Kruk and col-leagues [26] showed that women’s perceptions of the im-portance of facility delivery at the village level were associated with facility delivery, controlling for women’s individual perceptions. However, they did not provide in-formation on the perceptions of other influential people in the woman’s social network, including her husband and her mother-in-law. Stephenson and colleagues [25] used community-level variables to predict facility delivery in six African countries, but the variables they used were proxies

0

.2

.4

.6

.8

1

P

rob

ab

ilit

y

o

f

fa

c

ili

ty

d

e

liv

e

ry

1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 4

Community perceptions about MIL's attitudes on women delivering in facility

Woman/joint Husband only

for community norms and gender dynamics. For example, they used female educational attainment and level of facil-ity delivery to approximate social norms related to the power of women and facility delivery, respectively. Our study builds upon these results by using indicators that provide a more direct assessment of perceived community norms and women’s decision-making autonomy.

There have been mixed results related to the association between women’s decision-making autonomy and the use of maternal and child health services. Studies on women’s decision-making power have shown associations between higher decision-making autonomy and increased antenatal care use [23,30], having a normal body mass index [35], having a birth preparedness plan [36], childhood immu-nization [23], and sick child care [35]. However, the link-age between women’s decision-making autonomy and facility delivery in sub-Saharan Africa is less commonly studied and has shown mixed results [29,30]. In a study using the 2008 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey, Moyer and colleagues [3] found that women who did not participate in decision-making regarding their own health care were less likely to deliver in a health facility. However, when other factors were considered, such as maternal lit-eracy, health insurance coverage, and wealth, the associ-ation between women’s decision-making autonomy and facility delivery was no longer significant. When control-ling for perceptions of mothers-in-law and husbands (Table 3, Models 3–6), we find that women who have lower decision-making autonomy about their own health care have lower odds of facility delivery compared to women who are involved in health care decisions. This suggests that there is something unique about household dynamics and spousal communication, beyond maternal education and household wealth, in these two districts in Ghana. However, when controlling for perceptions of other women, decision-making by someone other than the woman or her spouse was significantly related to facility delivery (Table 3, Model 1). Women in this decision-making scenario need to be examined more closely as this was a rare response with a large confidence interval.

The relationship between women’s decision-making au-tonomy and facility delivery is even more important when the attitudes and beliefs in the community in which women live are considered (Figures 1 and 2). The associ-ation between community norms and facility delivery is greater (i.e., the slope is steeper) among women whose husbands make their health care decisions compared to women who are involved in health care decisions about their own health. This has important implications for the importance of community norms and how they interact with household gender dynamics. Communities that sup-port contemporary delivery practices may also be more supportive of gender equity with regards to household decision-making.

This study is not without limitations. First, this is a cross-sectional study and therefore it is not possible to determine the direction of causality. Possibly, women who deliver in a health facility become more favorable toward facility delivery after the fact rather than their at-titudes toward facility delivery influencing their delivery behaviors. Therefore, we are only able to show associa-tions with the available data. To better understand if at-titudes influence behaviors, it would be necessary to have longitudinal data on women’s attitudes toward fa-cility delivery prior to any pregnancy experience. The second limitation with these data is that we are using perceived attitudes of men and mothers-in-law. Unfortu-nately, data from these influential individuals were not collected in this study. That said, there is prior research that shows that perceptions of attitudes and norms are important to understanding health behaviors [37] and might matter more than actual attitudes in influencing health behaviors [38]. Third, responses of women’s atti-tudes and their perceptions of their husbands and mothers-in-law were correlated which meant that we were not able to determine if one is more influential than the other. Finally, given our use of quantitative data, it is not possible to answer the questions of“why” and “how” autonomy and community-level attitudes in-fluence behaviors. This can be explored with qualitative data that goes into depth on decision-making autonomy and community attitudes simultaneously.

Future studies of barriers to women’s use of facility de-livery in Ghana and elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa should consider the role of decision-making autonomy and community norms. To do this correctly will require collecting data from multiple players (e.g., women, part-ners, mothers-in-law, and health care providers) as well as collecting data longitudinally to better understand the multiple influences. In particular, over time, women’s at-titudes may change as well as community atat-titudes. Fol-lowing communities and women longitudinally will permit a determination of which of these are the most important for future program development.

Conclusions

improvement project staff. Community conversations in-volve influential individuals and encourage discussion on the importance of men attending antenatal and delivery care and the importance of delivering in a health facility. The final evaluation will permit an assessment of whether women (and their network members) who were exposed to these types of interventions were more likely to deliver in a health facility compared to women who were not exposed to these interventions. Second, programs that undertake community outreach activities to change com-munity norms are likely to be more effective than pro-grams that simply target individuals. By addressing community norms related to institutional delivery, espe-cially birth location preferences among women and men, programs have the potential to help families become better prepared for obstetric emergencies should complications arise [39]. With these types of interventions, community norms should become more favorable toward facility deliv-ery and women will be more likely to deliver in safer settings, even if they do not have the decision-making authority. Overall, maternal and child health programs that involve influential individuals and communities are likely to be the most successful at helping Ghana and other sub-Saharan African countries to attain their Millennium Development Goals for women’s and children’s health.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’contributions

ISS, WTS, and KS conceived of the topic, ISS performed the majority of the analyses, ISS and WTS wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed to the intellectual content and writing process of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sodzi Sodzi-Tettey and Pierre Barker for their review and feedback into an earlier draft of this paper. Funding for the data collection and analysis of this paper came from a subcontract to the University of North Carolina from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). The data reported in this paper are part of baseline and midline data collected as part of the evaluation of the IHI Maternal and Newborn Referrals Project of Project Fives Alive! funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. We are also grateful to the Carolina Population Center for training support (T32 HD007168) and for general support (R24 HD050924) during the development of this manuscript.

Received: 30 July 2014 Accepted: 19 November 2014

References

1. WHO and UNICEF:Accountability for Maternal, Newborn and Child Survival:

The 2013 Update.Geneva: WHO; 2013. http://www.who.int/woman_child

_accountability/ierg/reports/Countdown_Accountability_2013Report.pdf. Accessed July 23, 2014.

2. Ghana Statistical Service:Ghana Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey with an

Enhanced Malaria Module and Biomarker, 2011, Final Report.Accra, Ghana:

2011. http://www.unicef.org/ghana/Ghana_MICS_Final.pdf. Accessed July 23, 2014.

3. Moyer CA, Adongo PB, Aborigo RA, Hodgson A, Engmann CM, DeVries R:

“It’s up to the woman’s people”: How social factors influence facility-based delivery in rural northern Ghana.Matern Child Health J2013. doi:10.1007/s10995-013-1240-y

4. WHO:Making Pregnancy Safer: The Critical Role of the Skilled Attendant.

Geneva: WHO, ICM, FIGO; 2004. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2004/ 9241591692.pdf. Accessed July 23, 2014.

5. WHO: Health services coverage statistics. http://www.who.int/whosis/ whostat/EN_WHS09_Table4.pdf. Accessed July 23, 2014

6. Ghana Statistical Service (GSS):Ghana Health Service (GHS), and ICF Macro.

2009. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2008.Accra, Ghana: GSS, GHS,

and ICF Macro; 2009. http://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR172/SR172. pdf. Accessed July 23, 2014.

7. Doku D, Neupane S, Doku PN:Factors associated with reproductive health care utilization among Ghanaian women.BMC Int Health Hum Rights2012,

12:29. http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1472-698X-12-29.pdf. 8. Johnson FA, Padmadas SS, Brown JJ:On the spatial inequalities of

institutional versus home births in Ghana: a multilevel analysis.

J Community Health2009,34:64–72.

9. Penfold S, Harrison E, Bell J, Fitzmaurice A:Evaluation of the delivery fee exemption policy in Ghana: population estimates of changes in delivery service utilization in two regions.Ghana Med J2007,41:100–109. 10. Finlayson K, Downe S:Why do women not use antenatal services in

low- and middle-income countries? A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies.PLoS Med2013,10(1):e1001373.

11. Pell C, Meñaca A, Were F, Afrah N, Chatio S, Manda-Taylor L, Hamel MJ, Hodgson A, Tagbor H, Kalilani L, Ouma P, Pool R:Factors affecting antenatal care attendance results from qualitative studies in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi.PLoS One2013,8(1):e53747.

12. Arthur E:Wealth and antenatal care use: Implications for maternal health care utilization in Ghana.Heal Econ Rev2012,2(14):14. doi:10.1186/2191-1991-2-14.

13. Mwangome FK, Holding PA, Songola KM, Bomu GK:Barriers to hospital delivery in a rural setting in coast province. Kenya: community attitude and behaviours.Rural Remote Health2012,12:1852.

14. Ykong VN, Rush KL, Bassett-Smith J, Bottorff JL, Robinson C:Women’s experiences of seeking reproductive health care in rural Ghana: challenges for maternal health service utilization.J Adv Nurs2010,

66(11):2431–2441.

15. Gething PW, Johnson FA, Frempong-Ainguah F, Nyarko P, Baschieri A, Aboagye P, Falkingham J, Matthews Z, Atkinson PM:Geographical access to care at birth in Ghana: a barrier to safe motherhood.BMC Public Health 2012,12:991.

16. Kitui J, Lewis S, Davey G:Factors influencing place of delivery for women in Kenya: an analysis of the Kenya demographic and health survey, 2008/2009.BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth2013,13:40.

17. Matsuoka S, Aiga H, Rasmey LC, Rathavy T, Okitsu A:Perceived barriers to utilization of maternal health services in rural Cambodia.Health Policy 2010,95:255–263.

18. Singh K, Osei-Akoto I, Otchere F, Sodzi-Tettey S, Barrington C, Huang C, Fordham C, Speizer I:Ghana’s national health insurance scheme and maternal and child health: a mixed methods study.2014, Under review. 19. Dzakpasu S, Soremekun S, Manu A, ten Asbroek G, Tawiah C, Hurt L, Fenty J,

Owusu-Agyei S, Hill Z, Campbell OMR, Kirkwood BR:Impact of free delivery care on health facility delivery and insurance coverage in Ghana’s Brong Ahafo Region.PLoS One2012,7(11):e49430.

20. Mensah J, Oppong J, Schmidt C:Ghana’s national health insurance scheme in the context of the health MDGs: an empirical evaluation using propensity score matching.Health Econ2010,19:95–106. 21. D’Ambruoso L, Abbey M, Hussein J:Please understand when I cry out in

pain: Women’s accounts of maternity services during labour and delivery in Ghana.BMC Public Health2005,5:1–40.

22. Choudhury N, Ahmed SM:Maternal care practices among the ultra poor households in rural Bangladesh: a qualitative exploratory study.

BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth2011,11:15.

23. Allendorf K:Couples’reports of women’s autonomy and health-care use in Nepal.Stud Fam Plann2007,38(1):35–46.

24. Moyer CA, Mustafa A:Drivers and deterrents of facility delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review.Reprod Health2013,10:40. 25. Stephenson R, Baschieri A, Clements S, Hennink M, Madise N:Contextual

influences on the use of health facilities for childbirth in Africa.Am J

Public Health2006,96(1):84–93.

27. Danforth EJ, Kruk ME, Rockers PC, Mbaruku G, Galea S:Household decision-making about delivery in health facilities: evidence from Tanzania.

J Health Popul Nutr2009,27(5):696–703.

28. White D, Dynes M, Rubardt M, Sissoko K, Stephenson R:The influence of intra familial power on maternal health care in Mali: perspectives of women, men and mothers-in-law.Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health2013,

39(2):58–68.

29. Singh K, Bloom S, Haney E, Olorunsaiye C, Brodish P:Gender equality and childbirth in a health facility: Nigeria and MDG5.Afr J Reprod Health2012,

16(3):123–129.

30. Story WT, Burgard SA:Couples’reports of household decision-making and the utilization of maternal health services in Bangladesh.Soc Sci Med 2012,75:2403–2411.

31. Allendorf K:The quality of family relationships and use of maternal healthcare services in India.Stud Fam Plann2010,41(4):263–276. 32. Henderson R, Sundaresan T:Clustering sampling to assess immunization

coverage: a review of experience with a simplified sampling method.

Bull World Health Organ1982,60(2):253–260.

33. Adjiwanou V, LeGrand T:Does antenatal care matter in the use of skilled birth attendance in rural Africa: a multi-country analysis.Soc Sci Med 2013,86:26–34.

34. Ai C, Norton EC:Interaction terms in logit and probit models.Econ Lett 2003,80(1):123–129.

35. Singh K, Bloom S, Brodish P: Gender equality as a means to improve maternal and child health in Africa.Health Care for Women International. 2013. doi:10.1080/07399332.2013.824971.

36. Becker S, Fonseca-Becker F, Schenck-Yglesias C:Husbands’and wives’ reports of women’s decision-making power in Western Guatemala and their effects on preventive health behaviors.Soc Sci Med2006,

62(9):2313–2326.

37. Fishbein M:A reasoned action approach to health promotion.Med Decis

Making2008,28(6):834–844.

38. Speizer IS:Are husbands a barrier to women’s family planning use? The case of Morocco.Soc Biol1999,46(1–2):1–16.

39. Cofie LE, Barrington C, Singh K, Sodzi-Tetty S, Barker P, Akaligaung AJ: Birth location preferences of mothers and fathers in rural Ghana. Working paper. 2014.

doi:10.1186/s12884-014-0398-7

Cite this article as:Speizeret al.:Factors associated with institutional delivery in Ghana: the role of decision-making autonomy and community norms.BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth201414:398.

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central and take full advantage of:

• Convenient online submission

• Thorough peer review

• No space constraints or color figure charges

• Immediate publication on acceptance

• Inclusion in PubMed, CAS, Scopus and Google Scholar

• Research which is freely available for redistribution