THE THEORY AND MEASUREMENT OF

RECIPROCITY

J o h n R o b e rt N cw h u icl

U n iv e rs ity College, L o n d o n

S u bm itted fo r the degree o f

D o c to r o f P h ilo so p h y

All rights reserved

INFORMATION TO ALL USERS

The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.

In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript

and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed,

a note will indicate the deletion.

uest.

ProQuest 10015814

Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author.

All rights reserved.

This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code.

Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC.

ProQuest LLC

789 East Eisenhower Parkway

P.O. Box 1346

A ckn o w le d g m e n ts

T h e re are m a n y people w h o d ire c tly and in d ire c tly , k n o w in g ly and u n k n o w in g ly

have c o n trib u te d to the present thesis.

In p a rtic u la r I w o u ld lik e to re co rd m y debt to P rolessor A d ria n F u rn h a m f o r his in it ia l d ecision to accept me u n d e r his tutelage, f o r his c o n tin u e d b elief, s u p p o rt and encouragem ent, w ith o u t w h ic h I w o u ld su re ly have faltered.

A ls o to L y n n e f o r the patience th a t she has s h o w n in th e tim es w h e n I was ‘ o n m y

p e rc h ’ w o r k in g at hom e.

T o D r J o h n Cape w h o o rig in a lly suggested th a t I co nte m p la te fu r th e r s tu d y and m y colleagues at w o r k w h o have been bemused at tim es b y m y ‘ so un d in g o u t ’ ideas in th e ir presence.

T o those w h o I have n o t m e n tio n e d specifically, i f as y o u read th is , y o u recognise

H a ll, 1988). H o w e v e r, a re v ie w o f the existin g re c ip ro c ity lite ra tu re fo u n d lit t le

consensus o n th e fo rm a l th e o ry and d e fin itio n o f re c ip ro c ity . D e fin itio n s o f

re c ip ro c ity varied by stud y and used measures w ith inadequate p s y c h o m e tric p ro p e rtie s . O ld e r adults (50 years+ ) were p a itic ip a n ts in 49% o l the studies re vie w e d. A l l th e c u rre n t studies re p o rte d used a p re d o m in a n tly stud e nt j)o p u la tio n .

U s in g e x p lo ra to ry fa c to r analysis (p rin c ip a l com ponents, va rim a x ro ta tio n ) a value

based re c ip ro c ity measure w it h three factors (in s tru m e n ta lity , s o c ia lity and guidance) was developed. T h e scale com prised 132 item s. T h ere was a bias to p la c in g h ig h e r values o n th e receipt o f favours. F u rth e r d eve lo p m en t o f th e scale reduced th e measure to 72 item s. I 'lie receiving guidance fa c to r was c o rre la te d w it h fa m ily m em bers ( r = .23; n = 98; p < .05); and the g iv in g guidance fa c to r w it h frie n d s

( r = .22; n = 98; p < .05).

In a fu r th e r re fin e m e n t of the re c ip ro c ity measure tw o scales (each of 15 item s) w ere developed, k o u n t And Mecomn (C ro n b a c h ’s alpha = .97). B o th scales w ere

fo u n d to c o rre la te s ig n ific a n tly w it h social n e tw o rk size ( r = .34; n = 64; p < .01). S ig n ific a n t c o rre la tio n s betw een the IP R I re c ip ro c ity scale (T ild e n , N e ls o n , & M a y , 1990) and b o th Ico u n t ( r = .52; n = 93; p < .01) AndM ecount (r= .4 4 ; n = 93; p < .01) s u p p o rt the c o n s tru c t v a lid ity o f th e new re c ip ro c ity measure.

D iffe r e n t re la tio n s h ip s w it h th e in d ex measures o f social s u p p o rt w ere fo u n d as a fu n c tio n o f th e c a lc u la tio n m e th o d (difference; ra tio ; m u ltip lic a tio n ). A d is tin c tio n betw een enacted and perceived re c ip ro c ity was fo u n d s im ila r to th a t re p o rte d in the social s u p p o rt lite ra tu re (N e w la n d & F u rn h a m , 1999). A c o g n itiv e schema is

TA B LE O F C O N T E N T S

C H A P T E R 1: Introduction to the concept of Reciprocity

Page

R e c ip ro c ity in th e a n th ro p o lo g ic a l lite ra tu re 18

R cciproc ity in ilic e conom ic lite ra tu re 18 R e c ip ro c ity in the sociological lite ra tu re 20

R e c ip ro c ity in the p sy c h o lo g ic a l lite ra tu re 20

C H A P T E R 2: Reciprocity: A concept for integrating functional

and structural aspects of social support

Introduction 30

ISSI: In te rv ie w Schedule fo r Social In te ra c tio n 62 P R Q : Personal Resource Q u e s tio n n a ire 63 PSR: P ro v is io n s o f Social R elations 63

SPS: Social P ro v is io n s Scale 64

P S S -F r/Fa: Perceived Social S u p p o rt-F rie n d s /F a m ily 66

ISSB: In v e n to ry o l S ocially S tippot liv e B ehaviours 67 N S S Q : N o rb c c k Social S u p p o rt Q u e s tio n n a ire 68 SSQ; Social S u p p o rt Q u e s tio n n a ire 69 IS EL: In te rp e rs o n a l S u p p o rt E v a lu a tio n L is t 70

lESS: In strum e n tah E xpressive Scales 71

S u m m a ry co nclusio n s o n the c o n te n t areas o f th e re c ip ro c ity measure 72

Perceived o r enacted re c ip ro c ity 73

S tru c tu ra l measures 77

M e th o d

P a rtic ip a n ts 84

In s tru m e n ts 87

P rocedure 88

R e su lts

IS EL 81

ISSB 95

S S Q (N ) f u ll scale 97

S S Q (N ) s h o rt fo rm 99

S SQ (Q ) f u ll scale 99

S SQ (Q ) s h o rt fo r m 100

IL L S 100

in te r and lii ir a Scale C o rre la tio n s 104

D is c u s s io n 110

C H A P P E R 4: I n i t i a l d e v e lo p m e n t o f th e r e c ip r o c ity m easure

I n t r o d u c t io n

In d e x variables fo r th e re c ip ro c ity measure 115

R e c ip ro c a tio n Id e o lo g y 121

Locus o l C o n tr o l 121

Method

P a rtic ip a n ts 124

In s tn in ic n ls 124

P ro ced u re 128

lie s II Its

F a c to r analysis o f th e IS E L 129

F a c to r analysis o f th e ISSB 130

D e v e lo p m e n t o f the re c ip ro c ity measure 133 G iv e and Receive factors and N e tw o r k D e n s ity 141

F a c to r A n a ly s is o f the E iscnhcrgcr R e c ip ro c a tio n Id e o lo g y Scale 143

Th re e co n stru cte d re c ip ro c ity measures 148

Discussion 152

C H A P T E R 5: Development of the reciprocity measure:

Relations with family and friends

Introduction 159

Method

P a rtic ip a n ts 164

In s tru m e n ts 164

P rocedin e 164

Results

Discussion 188

C IIA P rRK 6: I hc reciprocity measure and its relationship to

functional and structural measures

Introduction 196

Method

P a rtic ip a n ts 202

In s tru m e n ts 202

P rocedure 203

Results

F a c to r analysis o f th e re c ip ro c ity measure 204 K (*('i])r()cily and n d w m h d e n sity as a c o n tin u o u s variable 208 K e c iju o c ity and lu M w o rk d e n sity as a d ic h o lo n io u s variable 209

R e c ip ro c ity and self-esteem 209

E x a m in a tio n o f th e c o n stru cte d re c ip ro c ity measures 210

Discussion 214

C H A P T E R 7: Confirm atory factor analysis and assessment of the

validity of the developed reciprocity measure

M ethod

P a rtic ip a n ts 222

In s tru m e n ts 222

P rocedure 223

Results

F a c to r analysis o f th e IP R I scales 224 F a c to r analysis o i th e Ic o u n t and M e c o u n t scales 226

R e la tio n s h ip s betw een IP R I, Ic o u n t and M e c o u n t scales 231 Ic o u n t, M e c o u n t and n e tw o rk d e n sity as a c o n tin u o u s variable 232 Ic o u n t, M e c o u n t and n e tw o rk d e n sity as a d ic h o to m o u s variable 232 Ic o u n t, M e c o u n t and self-esteem 233

Discussion 238

C H A P T E R 8: The effects of physical relocation on

social networks and perceived social support

Introduction 242

Method

P a rtic ip a n ts 247

In s tru m e n ts 248

P rocedure 248

Results

Social s u p p o rt 251

N e tw o r k d e n s ity 252

N e tw o r k size 254

Self-esteem 256

C H A P T E R 9; Overview of the theory and measurement of reciprocity

S u m m a ry co nclusio n s 263

T o w a rd s a th e o ry o f re c ip ro c ity 267 M easurem ent o f generalised re c ip ro c ity 268

F u tu re research areas 270

R EFERENCES 272

A P P E N D IC E S

A p p e n d ix 1 O u tp u t o l the la c to r analysis o l the IS EL-ch 3 296 A p p e n d ix I I O u tp u t o f the fa c to r analysis o f the ISSB-ch 3 298 A p p e n d ix I I I O u tp u t o f th e fa c to r analysis o f S S Q (N )-ch 3 300

A p p e n d ix IV O u i p u t o l ilie fa c to r analysis o f SSQ (Q )-ch 3 303 A p p e n d ix V O u tp u t o f th e fa c to r analysis o f the lE E S-ch 3 306 A p p e n d ix V I O u tp u t o f th e fa c to r analysis o f th e IS E L-ch 4 308 A p p e n d ix V I I O u tp u t o f th e fa c to r analysis o f th e ISSB-ch 4 310 A p p e n d ix V I l l O u tp u t o f the fa c to r analysis o f the

TA B LE O F TABLES

T a ble Page

2.1 D e fin itio n s o f R e c ip ro c ity 34

2.2 Studies id e n tifie d as using the concept o f

re c ip ro c ity in social s u p p o rt 48 2.3 S u m m a ry o f Social S u p p o rt Scales review ed b y conceptual base 60

2.4 R epresentative T a xon o m ie s o f Social S u p p o rt 61 2.5 S econd-O rder F a c to r Loadings fo r the social p ro v is io n s 64 2.6 SPS c o rre la tio n s w it h SSQ and ISSB 65 2.7 F a c to r in te rc o rre la tio n s re p o rte d b y

M a n c in i and B lieszner (1V92) 65

2.8 S im u la tio n o f the c o rre la tio n s between social s u p p o rt

and the c rite rio n measures 74

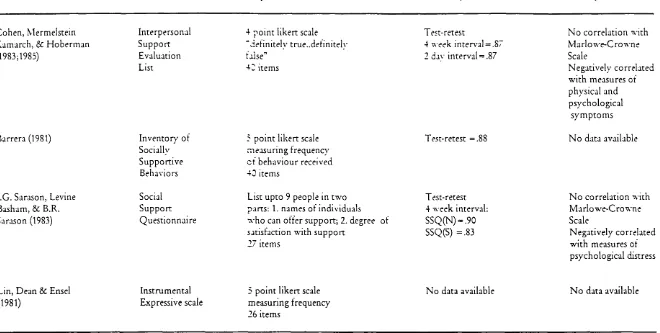

3.1 S u m m a ry o f Social S u p p o rt Measures 86

3.2 S u m m a iy Scale Statistics 90

3.3 C o rre la tio n s betw een the fa c to r scores and o rig in a l scale sco rin g 91 3.4 IS E L (B elonging; Self-Est; A pp ra isa l; T angible) 93

3.5 In tc rc o rrc la tio n s o f IS EL subscales 94 3.6 ISSB (G u id a n c e ;E m o tio n a l S u p p o rt;T a n g ib le Assistance) 95

3.7 In te rc o rre la tio n s o f th e ISSB sub-scales 97 3.8 L oadings o f item s o n the u n ro ta te d

F a c to r M a trix o f the SSQ (N ) 98

3.9 Loadings o f item s on the u n ro ta te d

F a c to r M a tr ix o f the SSQ(S) 100 3.10 F a c to r S tru c tu re o f th e lESS ( C o m p a n io n s h ip ;

M o n e ta ry P roblem s; C o m m u n ic a tio n p ro ble m s; D em ands; U n n a m e d F actor)

c o n tro llin g fo r sex 108 3.15 R esults o f th e m u ltip le regression analysis 109 3.16 P a rtia l c o rre la tio n s c o n tro llin g fo r sex fo r s p lit G H Q scores 110

3.17 V ariance accounted fo r in p u b lis h e d studies o f

social s u p p o rt measures 111

4.1 Item s generated f o r re ce ivin g favo u rs 125 4.2 P s y c h o m e tric p ro p e rtie s o f th e RIS; LCS; JW S & G JW BS 127 4.3 D e m o g ra p h ic c o rre la tio n s o f the sample 128 4.4 S u m m a ry results o f a fa c to r analysis o f the IS E L 129

4.5 S um m a ry results o l a la c to r analysis ol the ISSB 130 4.6 C o rre la tio n s betw een the ISSB and ISEL 131 4.7 C o n gru e nce co efficie n ts between subscales o f th e IS E L and ISSB 133

4.8 S u m m a ry results o f a fa c to r analysis on g iv in g favo u rs 135 4.9 3 la c to r s o lu tio n o l the G ivc-value scale 136 4.10 3 fa c to r s o lu tio n o f the receive-value scale 137 4.11 In te rc o rre la tio n s between in s tru m e n ta lity , s o c ia lity ,

and gu id an c e 1 actors 139

4.12 C o rre la tio n s o f th e give factors and the ISEL and ISSB subscales 140

4.13 C o rre la tio n s o f th e receive factors and the

IS E L and ISSB subscales 140

4.14 C o rre la tio n s betw een factors and d e n sity c o n tro llin g fo r

n e tw o r k size 141

4.15 F a c to r in te rc o rre la tio n s as a lu n c tio n o l

h ig h and lo w d e n s ity (m edian sp lit) 142 4.16 S u m m a ry results o f a fa c to r analysis o f the Eisenberger scale 143 4.17 Scale item s o f the R e c ip ro c a tio n -Id e o lo g y scale 144 4.18 C o rre la tio n s betw een R e c ip ro c a tio n Id e o lo gy Q u e s tio n n a ire

4.19 C o rre la tio n s o l the give and receive factors w it h

th e Just W o rld Scales 145

4.20 Means and Standard D e v ia tio n s o n the I, P, and C scales 146 4.21 C o rre la tio n s betw een the give and receive scales

and locus o f c o n tro l 147

4.22 C o rre la tio n s betw een M a rlo w e -C ro w n e and facto rs 147

4.23 Means and S tandard D e v ia tio n s o f the ‘ R a tio ’

re c ip ro c ity variables 148

4.24 C o rre la tio n s o f th e ‘ r a tio ’ re c ip ro c ity variables, IS EL, ISSB 148 4.25 Means and Standard D e v ia tio n s o f

th e ‘ D iffe re n c e ’ re c ip ro c ity variables 149 4.26 C o rre la tio n s betw een R e c ip ro c ity difference scores

and ISEL and ISSB 150

4.27 Means and Standard D e v ia tio n s o l the

m u ltip lic a tiv e re c ip ro c ity measure 150 4.28 C o rre la tio n s betw een R e c ip ro c ity

m u ltip lic a tiv e scores and ISEL and ISSB 150

4.29 C o rre la tio n s betw een d e n sity and re c ip ro c ity measures

c o n tr o llin g f o r n e tw o rk size 151

4.30 C .orrelations between the constructed re c ip ro c ity

measures and th e in d e x measures 152

4.31 C o rre la tio n s betw een M a rlo w e -C ro w n e and

re c ip ro c ity measures 152

4.32 Average c o rre la tio n s betw een the ISEL, ISSB

and g ive /rece ive factors 153

4.33 Average c o rre la tio n s between the ISEL, ISSB

and th e three re c ip ro c ity measures 153 4.34 C o rre la tio n s between n e tw o rk d e n sity and

th e IS E L and ISSB 156

5.5 T h e means and standard d eviations o f the

give fre qu e ncy values 173

5.6 S tru c tu re M a tr ix loadings o f th e G ive

va liic-rcccivc value fa c to r analysis 176 5.7 Loadings o l the give value item s on

th e S o c ia lity and G uidance factors 177

5.8 L oadings o f th e receive value item s o n

th e S o c ia lity and G uidance factors 177 5.9 Loadings o f th e give value item s on

(lie S o iia h iy and G u id a n te lat lo rs -n ia x in in m lik e lih o o d 178

5.10 Loadings o i the receive value item s on

th e S o c ia lity and G uidance fa cto rs -m a x im u m lik e lih o o d 178

5.11 C o rre la tio n s betw een factors 181

5.12 ( Congruence c o e liic ie n ls bel ween

factors p roduced in chapter 4 and th e c u rre n t factors 181

5.13 r-tests fo r paired samples 182

5.14 C '.orrelalions between the re c ip ro c ity

facto rs b y re c p ro x (1,2) 182

5.15 M ean n u m b e r o f people re p o rte d in p o p u la tio n surveys 184 5.16 M ean values of give and receive favours b y n e tw o rk re la tio n s h ip 184 5.17 C o rre la tio n s betw een S o c ia lity , G uidance and num be rs o f

F a m ily and F riends 185

5.18 C o rre la tio n s between give and receive favours w ith fa m ily

and re c ip ro c ity factors 186

5.19 C o rre la tio n s between give and receive favours w it h frie n d s

and re c ip ro c ity factors 186

5.21 C o rre la tio n s betw een th e constructed re c ip ro c ity measures

in the present s tu d y 188

5.22 C o rre la tio n s betw een the constructed re c ip ro c ity measures

in chapter 4 188

5.23 C la rk et.a l.(1987) : M ean n u m b e r o f b o x checks

b y re la tio n s h ip x o p p o r tu n ity 193

6.1 C o m p a riso n o f judgem ents b y respondents

and researchers on g iv in g and receiving su p p o rt (m o d ifie d table) 197

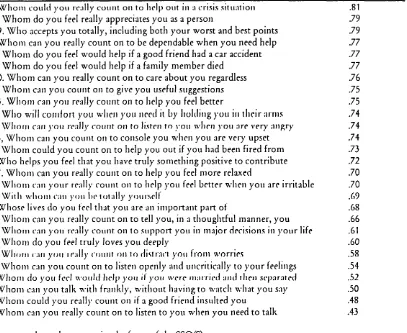

6.2 Item s fo r th e Ic o u n t scale 203

6.3 D e m o g ra p h ic c o rre la tio n s 204 6.4 Ite m loadings, means and standard d eviations o f Ic o u n t 205 6.5 Ite m loadings, means and standard deviations o f M e c o u n t 206

6.6 C o rrc J jllo i)': o l Ic n im i, M e c o im i w iih ISF.I.,

M a rlo w e -C ro w n e and n e tw o rk size 207 6.7 C o rre la tio n s o f Ic o u n t and M e c o u n t scales w it h

IS EL, D e n s ity > = 2 8 o r < 2 8 209 6.8 S um m ary statistics o f llie constructed re c ip ro c ity measures 213 6.9 C o rre la tio n s o l R a tio c a n ,D ilfc a n ,M u ltic a n w it h ISEL,

Self-esteem, n e tw o rk size 213

6.10 O rig in a l (A ) and S im ulated (B) C o rre la tio n s o f

R a tio c a n ,D ilic a n ,M u ltic a n w it h ISEL & Self-esteem 214

6.11 C o m p a ris o n c o rre la tio n s re p o rte d in p re v io u s studies

betw een social s u p p o rt and social n e tw o rk size 215

7.1 Item s used on th e R e c ip ro c ity scale 223 7.2 D e m o g ra p h ic c o rre la tio n s 224

7.3 Eigenvalues and C iD iib a e h alphas lo r (lie

In te rp e rs o n a l R e la tio n s h ip In v e n to ry 224 7.4 F a c to r s tru c tu re and ro ta te d fa c to r loadings o f the

7.10 C o rre la tio n s o l Ic o u n t and M e c o u n t scales w it h IP R ,

D e n s ity > = 3 2 o r < 3 2 233 7.11 Results o f a d is c rim in a n t analysis u sin g IP R re c ip ro c ity

as I lie p r e d i c t o r variable 234

7.12 Results o f th e Regression o f Icount, M ecount o n IP R Ire c ip r o c ity 236

7.13 S um m ary statistics o f the co nstru cte d re c ip ro c ity measures 237 7.14 C o rre la tio n s o f co nstru cte d re c ip ro c ity

scores w it h IP R re c ip ro c ity 237 8.1 S liid y phases and me.isiires );iven 250

8.2 D e m o g ra p h ic c o rre la tio n s 250

8.3 IS E L scores b y phase 251

8.4 M ean values o i IS EL over phases b y lo c a tio n and sex 252

8.5 N e t w o r k d e n s ity scores b y phase 253

8.6 M ean values o f N e tw o r k d e n sity b y lo c a tio n and sex 254

8.7 N e tw o r k size scores b y phase 255

TA B LE O F F IG U R E S

FiguiÊ Page

2.1 G ra p h o f the n u m b e r o f p u b lic a tio n s c o n ta in in g

social s u p p o rt in the title 31

2.2 Q u o ta tio n s p ro p o s in g a lin ka ge betw een social s u p p o rt

and social n e tw o rk s 32

3.1 Scree chart fo r IS E L 91

3.2 Scree ch art fo r ISSB 96

3.3 Scree ch art fo r th e SSQ (N ) 98

3.4 Scree ch a rt f o r the SSQ (Q) 99

3.5 Scree ch art fo r the lESS 101

3.6 Scree ch art o f the h ig h e r o rd e r fa c to r analysis 104

4.1 Scree ch a rt fo r the IS E L 129

4.2 Scree ch art fo r th e ISSB 131

4.3 Scree chart lo r give la vo urs 135

4.4 O rig in a l d is tr ib u tio n o f n e tw o rk d e n s ity scores 141 4.5 D is tr ib u tio n fo llo w in g square ro o t tra n s fo rm a tio n o f

n e tw o r k d e n s ity scores 141

4.6 Scree ch art f o r the R IQ 144

4.7 N o rm a l P-P p lo t o i s o c ia lity (r) 157

5.1 Scree ch art f o r all give-receive item s 175 5.2 R epresentation o f give and receive o p tio n s 193

6.1 Scree chart o f Ic o u n t 205

6.2 Scree ch art o f M e c o u n t 206

6.3 O rig in a l disi r ib iii ion ol ncl w o rk d c n s iiy scores 208

6.4 D is tr ib u tio n fo llo w in g lo g a rith m ic tra n s fo rm a tio n

o f n e tw o rk d e n s ity scores 208

6.5 D is tr ib u tio n o i ra tio can 210

6.6 D is tr ib u tio n o i d iiic a n 211

7.3 Scree ch art o f M e c o u n t 227 7.4 D is tr ib u tio n o f n e tw o ric d en s ity 232 7.5 N o rm a lis e d d is trib u tio n o f n e tw o rk d e n s ity 232 7.6 P lo t o f the standardised residuals against

chapter 1: Introduction to the concept of reciprocity

T h e te rm ‘ r e c ip ro c ity ’ has various m eanings. In o rd e r to set th e c o n te x t f o r th e thesis, th e fo llo w in g ch ap ter fo rm s a preface to th e detailed lite ra tu re re v ie w c o n ta in e d in ch ap ter 2. I t sets the scene fo r th e s tu d y in g ‘re c ip ro c ity ’ w it h in p s y c h o lo g y .

R e c ip ro c ity has been used as an e x p la n a to ry concept fo r th e d eve lo p m en t o f

c u ltu re in th e a n th ro p o lo g ic a l lite ra tu re (e.g., Lévi-Strauss, 1974; Sahlins, 1965); f o r

b a rg a in in g in th e econom ic lite ra tu re (e.g., Blau, 1964) and f o r analysing g ro u p m e m b e rsh ip in th e sociological lite ra tu re (e.g., G o u ld n e r, 1960; G o u ld n e r, 1973). G e n e ra lly , h o w e ve r, the concept o f re c ip ro c ity has la rg e ly been neglected in th e p sych o lo g ic a l lite ra tu re .

A n e xce p tio n is th e lite ra tu re on health outcom es o f o ld e r adults. H o w e v e r, even in the la tte r lite ra tu re the concept o l re c ip ro c ity has been defined and measured d iffe re n tly in m ost studies thus, p re c lu d in g cross s tu d y com parisons. T h e varied te c h n ic a l d e fin itio n s have rendered re c ip ro c ity in to a m u ltifa c e te d and vague concept.

1 he lo llo w in g lo u r sections sum m arise re c ip ro c ity w it h in the a n th ro p o lo g ic a l,

e co n o m ic, so cio log ica l and p sych o lo g ica l lite ra tu re s as relevant to th e present thesis.

Reciprocity in the anthropological literature

III I lie anl h rn p n lo g ic a l lite ra tu re , the concept o f re c ip ro c ity is used to e x p la in th e em ergent social stru cture s o f fa m ily , n e ig h b o u rh o o d s and c u ltu re . Even in cu ltu re s

“ ...the co n n e ctio n s between m a teria l f lo w and social re la tio n s is re cip ro cal. A specilic social re la tio n m ay c o n s tra in a given

m o ve m e n t o f goods, b u t a specific tra n sa ctio n - ‘ b y th e same to k e n ’ - suggests a p a rtic u la r social re la tio n . I f frie n d s m ake g ifts, g ifts m ake

Irie n d s ” (ib id . p. 139).

H e id e n tifie d three fo rm s o f re c ip ro c ity : generalised re c ip ro c ity , w h e re assistance is g iven and, i f possible and necessary, returne d ; balanced re c ip ro c ity , d ire c t and

C(]ual exchange o f goods; and negative re c ip ro c ity , an a tte m p t to get so m e th in g fo r n o th in g w ith im p u n ity . T h e te rm ‘generalised r e c ip ro c ity ’ w o u ld best describe th e

p syc h o lo g ic a l concept u n d e r co n sid e ra tio n in th e present thesis.

In some c u ltures the iu le rre la lio iis h ip between the social s tru c tu re (social

re la tio n s), and fu n c tio n (the g ift exchanged) can be specified precisely. Y a n (1996) in a detailed stu d y o f a sm all C hinese village c o m m u n ity described “ fo u r o p e ra tin g rules o f g ift exchange” . T h e rules w ere th a t a ‘g o o d ’ person alw ays in teracts in a

re c ip ro c a l w a y; th a t the size o f a g ift sh o u ld c o n fo rm to th e e xistin g h ie ra rc h ic a l social o rd er; th a t the g ift s h o u ld reflect pre viou s in te ra c tio n s ; and th a t the re was a

d e fin e d e tiq u e tte in th e re tu rn o f gifts. R enqing (re c ip ro c ity ) was fo u n d to be a c e n tra lly im p o rta n t concept in the village system o f exchange w it h its c o n n o ta tio n o f social n o rm s and m o ra l o b lig a tio n s . Social p a rtic ip a tio n in th e villag e was dependent o n u n d e rstan d in g and c o m p ly in g w it h renqing, d e te rm in in g w h o was

reciprocated, w hen th e y w ere reciprocated and w h a t was reciprocated. T h us, th e

concept o f renqing has a d e o n to lo g ica l ra th e r th a n a u tilita ria n status and again can be encompassed w it h in th e concept o f generalised re c ip ro c ity .

Reciprocity in the economic literntiire

In th e econ o m ic lite n itu re , early attem pts b y social p sycho lo g ists to re fin e th e th e o re tic a l c o n c e p tio n o f resource exchange ty p ic a lly used e conom ic the o rie s f o r th e ir analyses. H o w e v e r, econom ic th e o ry , p er se, is u n lik e ly to p ro v id e a

com p re he n sive e xp la n a tio n o f w h y o r even h o w resource exchange occurs. A zero sum game using m o n e y , such th a t one person gains the a m o u n t th a t a n o th e r

person loses is easy to conceptualise. A s im ila r zero sum game u sin g n o n -m o n e ta ry p s y c h o lo g ic a l resources is harde r to conceptualise. A t least some fo r m o f p u ta tiv e m o n e y /p s y c h o lo g ic a l resource cu rre n c y exchange m echanism w o u ld be re q uired . A s p re v io u s ly discussed, such an in te rv e n in g process w o u ld in v a ria b ly be lin k e d to n o n -e c o n o m ic factors. E m p iric a l evidence also indicates th a t w h e n p re d ic tio n s based o n standard econom ic th e o ry are com pared w it h those fr o m social exchange

the o r}", even w it h in a perceived econom ic d om ain , standard econom ic th e o ry is p o o r ly su pp o rted . In a stu d y in ve stig a tin g wage n e g o tia tio n s i t was hypo the sise d th a t il o n ly e conom ic p rin c ip le s were o perating then em p loye rs sh o u ld t r y to o ffe r th e lo w e s t wages th a t w o rk e rs w o u ld accept and th a t w o rk e rs s h o u ld m a xim ise th e ir u t i l i t y by w o r k in g at the m in im u m level possible (K irc h le r, F e hr, ôc Evans,

1996). H o w e v e r, co -o p e ra tio n was fo u n d to be at a m u c h h ig h e r level th a n p re d ic te d b y e conom ic th e o ry , suggesting th a t re c ip ro c a tio n n o rm s w ere

in flu e n c in g the outcom es. E xp la n a tio n s based o n social exchange th e o ry assume th a t a d d itio n a l social n o rm s are o pe ra tin g and in p a rtic u la r th a t o f re cip ro ca l

exchange.

Reciprocity in the sociological literature

fo rm , makes tw o in te rre la te d , m in im a l demands: (1) people s h o u ld h elp those w h o have helped the m , and (2) people s h o u ld n o t in ju re

those w h o have helped th e m ....T o suggest th a t th e n o rm o f re c ip ro c ity is u niversa l is n o t, o f course, to assert th a t i t is

u n c o n d itio n a l. U n c o n d itio n a lity w o u ld , indeed, be at variance w it h the basic character o f th e re c ip ro c ity n o rm w h ic h im poses

o b lig a tio n s o n ly c o n tin g e n tly , th a t is, in response to th e benefits c o n fe rre d b y others. M o re o v e r, such o b lig a tio n s o f re p a ym e n t are c o n tin g e n t u p o n th e im p u te d value o f th e b e n e fit received

W h e th e r in fact there is a re c ip ro c ity n o rm s p e cifica lly

re q u irin g th a t re tu rn s lo r beneiits received be ccjuivalent is an e m p iric a l que stio n... E quivalence m ay have at least tw o fo rm s , the

sociological and p s y ch o d yn a m ic significance o f w h ic h are apt to be q u ite d is tin c t. In th e firs t case, h e te ro m o rp h ic re c ip ro c ity ,

equivalence m ay mean th a t the th in g s exchanged m a y be co n c re te ly d iffe re n t b u t sh o u ld be equal in value, as d efin e d b y th e actors in th e s itu a tio n . In the second case, h o m e o m o rp h ic re c ip ro c ity ,

equivalence m ay mean th a t exchanges s h o u ld be c o n c re te ly alike, o r id e n tic a l in fo rm , e ith e r w it h respect to the th in g s exchanged o r to th e circum stances u n d e r w h ic h th e y are exchanged” .

T h e concept o f h e te ro m o rp h ic re c ip ro c ity is s im ila r to th a t o f Salins ‘generalised re c ip ro c ity ', and h o m e o m o rp h ic re c ip ro c ity to th a t o f ‘ balanced r e c ip ro c ity ’ .

A lth o u g h the ‘ n o rm o f re c ip ro c ity ’ co n tin u es to be used e xte n sive ly in th e sociological lite ra tu re as an e xpla n a to ry concept (e.g., Burger, 1 lo rita , K in o s h ita , R o b erts, & Vera, 1997; Uehara, 1995), the m o st recent fo r m u la tio n (G o u ld n e r,

I lo w c v c r, the c n ip iric iil (Question ;is to w h e th e r th e re c ip ro c ity n o rm s p e cifica lly

requires th a t re tu rn s f o r benefits received be equivalent is testable. N o p u b lis h e d studies have been re p o rte d th a t evaluate th is question. T h e effect o f elapsed tim e o n re cip ro ca l b e h a v io u r has been studied. B urge r (et a h ,1997) fo u n d th a t

p a rtic ip a n ts o ffe re d a free so ft d r in k fro m a confederate w ere m o re lik e ly to

re spond to a subsequent im m ed ia te request fr o m the confederate to d e liv e r a le tte r.

H o w e v e r, a w eek la te r there was a s ig n ific a n tly lo w e r response to th e request. T h e

fin d in g suggests th a t the n o rm o f re c ip ro c ity defines a social ru le re q u irin g re c ip ro c a tio n w it h in a given tim e fram e, ra th e r th a n an open-ended o b lig a tio n to re tu rn la vo u rs.

i he second ih c m e o l l ecipi o c ily js e x e m p lilie d m I he w o rk o f W e llm a n (1988), w h o in a m a jo r s tu d y o l a w h o le c o m m u n ity in Canada (the East Y o r k c o m m u n ity in T o r o n to ) fo u n d that asym m etric reciprocal exchange b e h a v io u r defined

m e m b e rsh ip o f social groups w it h in the c o m m u n ity . R ecip ro cal exchange created n o n -ra n d o m social n e tw o rk s o f clusters and cross linkages. F in ite lim its w ere fo u n d w it h in these social n e tw o rk s w it h respect to the n u m b e r and in te n s ity o f ties th a t an in d iv id u a l c o u ld m a in ta in . In th e East Y o r k c o m m u n ity an in d iv id u a l

m a in ta in e d a m edian o f eleven active ties. T h e s tru c tu re and c o m p o s itio n o f these ties re su lted in m a rke d v a ria tio n in the ty p e , e xtent and b re ad th o f social s u p p o rt

available th ro u g h th e m .

Reciprocity in the psychological literature

d id n o t a ttrib u te any signiiicance to the s tru c tu ra l system in w h ic h resource exchange occurs. C u r re n tly social exchange the o rie s m in im is e o r ig n o re th e

re la tio n s h ip betw een fu n c tio n a l and s tru c tu ra l factors because o f th e d if fic u lty in

c o m b in in g th e disparate conceptual fra m e w o rk s o f social n e tw o rk analysis and

in d iv id u a l exchange processes.

F o r exam ple, static bias, in h e re n t in social n e tw o rk analysis, makes i t d iffic u lt to

conceive a d y n a m ic stru c tu re v a ry in g as fu n c tio n a l re q uirem en ts change.T herefore th e effects o f s tru c tu ra l factors can be conceptualised as variance to be c o n tro lle d

f o r ra th e r th a n a llo w e d to co vary. C o n verse ly, fu n c tio n a l facto rs can be conceived

o f as in le u lia iig c .ib le and ilic K 'lo rc as nol having an in llu e n c e on social n e tw o rk s tm c tu re . H o w e v e r, the concept of re c ip ro c ity needs to account f o r the c o n c u rre n t o p e ra tio n o f b o th s tru c tu ra l and fu n c tio n a l factors.

A f u n her d if fic u lty is th a t the concept o f re c ip ro c ity has been e m p lo ye d in an ^

/joc and u n syste m a tic w a y th a t prevents the c u m u la tiv e in c o rp o ra tio n o f fin d in g s . F o r exam ple, w h e n re p o rtin g th e results o f e xpe rim en ta l w o r k o n re c ip ro c ity th e te rm s ‘ n e tw o rk b a la n c in g ’ and ‘generalised re c ip ro c ity ’ are used im p ly in g th a t th e c o n s tru c t is being measured across the to ta l re p o rte d social n e tw o rk m em bers. In fact research on re c ip ro c ity across large social n e tw o rk s has n o t y e t been re p o rte d .

T h e concept o f re c ip ro c ity has been used to account fo r p s y c h o lo g ic a l w e ll-b e in g b y c lin ic a l researchers w o rk in g w it h in m ental hea lth (M eeks & M u rre ll, 1994;

S im m o n s, 1994); o ld e r people (In g e rs o ll-D a y lo ii & A iito n u c c i, 1988) and le a rn in g

In sin nn i;iry, llio r o n r r p i o f re c ip ro c ity m ;iy p ro v id e a lin ka g e to th e tra n s a c tio n a l n atu re o f resource exchange w it h social structures. F u rth e r, re c ip ro c ity m a y

p o te n tia lly lin k th e s tru c tu ra l and fu n c tio n a l aspects o f p s y c h o lo g ic a l w e ll-b e in g . I lo w e v c r, the natu re ol these linkages can o n ly be u nd e rs to o d i f re c ip ro c ity is d efined and measured in a w a y th a t allo w s com parative analysis .

S ocial s u p p o rt a n d re c ip ro c ity

O n e research area th a t p ro vid e s an o p p o rtu n ity to investigate th e re la tio n s h ip s betw een fu n c tio n a l and s tru c tu ra l factors is th a t o f social s u p p o rt. T h e social s u p p o rt lite ra tu re can be considered as an amalgam o f tw o m a jo r research areas, tlia t o f resource exchange and social n e tw o rk s . In te g ra tin g these tw o research areas has alw ays been regarded as im p o rta n t a tta in m e n t and there have been a tte m p ts at

.ic liic v /iig ,1 ilie o /riiV .i) ',ynl he,is (e.g., W elim .m , 1988). H o w e v e r, social n e tw o rk researchers w o rk in g in the area o l social su pp o rt c o n tin u e to develop explan a tion s

based on n e tw o rk s tru ctu re , using concepts o f p ow er, prestige, c e n tra lity , and n e tw o rk d en sity. I ’lie te rm the ‘ socio-social n e tw o rk ’ has been reserved lo r th is area o r system -centred n e tw o rk s (W ilc o x & B irk e l, 1983). S im ila rly social p sych o lo g ists researching social s u p p o rt c o n tin u e to use n e tw o rk size as a p ro x y

f o r social n e tw o rk variables. Measures and procedures th a t go b e y o n d the in d iv id u a l level o th e r th a n n e tw o rk size are seldom used. W h ile a focus o n th e ‘person-social n e tw o r k ’ is recom m ended, the m a jo r research focus c o n tin u e s to

exam ine the fu n c tio n a l natu re o f receiving social s u p p o rt and its re la tio n s h ip to p h ysica l and p sych o lo g ic a l w e ll-be in g. F o u r p o te n tia l reasons can be advanced to e xplain the reluctance in researching the person-social n e tw o rk re la tio n s h ip . F ir s tly , c o rre la tio n s betw een n e tw o rk variables and measures o f social s u p p o rt are

ty p ic a lly lo w . H o w e v e r, th o u g h re p o rte d co rre la tio n s between n e tw o rk s i/c and social s u p p o rt are lo w , th e y are co ns is te n tly p o s itiv e (e.g., N e ls o n , B re n t-H a ll, Sc]uire, &: W alsli-B ow ers, 1992). T he lo w co rre la tio n s p o te n tia lly reflect th e fact

S econdly, social s u p p o rt th e o ris ts have u s u a lly considered social s u p p o rt as a u n id im c n s io n a l c o n s tru c t o pe ra tin g at the in d iv id u a l level. E x te rn a l social

re la tio n s h ip s are th e n considered to have secondary im p o rta n c e in th e e x p la n a tio n

o f p s y c h o lo g ic a l w e ll-b e in g . C h a p te r tw o w i l l m o re exte n sive ly analyse and discuss

th e m u ltid im e n s io n a l natu re o f social s u p p o rt.

T h ir d ly , th e re is a te n d en cy to focus o n th e receipt o f s u p p o rt resources. I t is b ro a d ly assumed th a t s u p p o rt is u n id ire c tio n a l fr o m a p ro v id e r to a re c ip ie n t. T h e b id ire c tio n a lity o f social s u p p o rt has been n o te d b u t n o t exam ined in detail:

"T h e '.o( ial j)\y ( h ological aspects o f th is p h e iio m e iio n -th e stu d y o f

social s u p p o rt as an in terpe rso n al tra n sa ctio n th a t in v o lv e s b o th a p ro v id e r o f s u p p o rt and a re cip ie n t- is n e a rly absent” (V in o k u r, S chul, & C aplan, 1987).

Social s u p p o rt as tra nsa ctio na l, and hence re cip ro cal, has been id e n tifie d as th e o re tic a lly s ig n ific a n t (Leavy, 1983; Sarason, Sarason, dc Pierce, 1990a) b u t th e

e x p e rim e n ta l lite ra tu re separates in to d ire c t effects o f social s u p p o rt in studies lo o k in g at s tru c tu ra l variables and b u ffe rin g effects fo u n d in studies o f fu n c tio n a l

variables (C o h e n & W ills , 1985).

A fo u rth reason not investigating re cip ro e ity is the lack o f a measurement scale. Scales that do include a measure o f re c ip ro c ity often use a single item to indicate

how much support has been given and received by the person over the total n e tw o rk. A ssum ing that the measure is re lia b le , the demand bias in such a d ire c t

ilieinsclves as o ffe rin g more than they receive. Consequently such a bias w o u ld

its e lf be evident in the se lf-re p ortin g o f g iv in g m ore than they received, a fin d in g that is typical in the few studies that have looked at re c ip ro c ity .

In studies that consider the difference in support provided by k in and n o n -kin there are indications that the nature o f the bias is towards perceiving that more support is

received from kin than given, and that more support is offered to non -kin than is

received. When measurement scales do use m ore items, d iffe re n t problem s are encountered. T y p ic a lly re c ip ro c ity is calculated as the d ifference between g iv in g and re ce ivin g as measured by tw o scales containing the same items but rew orded. A m ajor problem is that the re lia b ilitie s o f the tw o scales operate to reduce the re lia b ility o f the re c ip ro c ity scale (e ffe c tiv e ly the diffe re n ce score).

A n equation fo r calculating the re lia b ility o f a d ifference score is g iven by T ild e n

and Sic w an (198.S) :

p D D = p xx a ^ x + p yy o ’y - 2 p x y o x o y

O'X - f o ’y - 2 pxy ox oy

W here p D D = re lia b ility o f R eciprocity difference scores

pxx = re lia b ility o f G ive scores

p y y = r e lia b ility o f Receive scores

O x = variance o f G ive scores o^y = variance o f Receive scores

p x y = co rrelation between Receive and G ive scores

Inspection o f equation (1) shows that i f the co rre la tio n (p x y ) between the tw o scales

fro m w h ich the d illc rc n c c is calculated is high ih c ii the re lia b ility o f the diffe re n ce

score is less than the in d iv id u a l scales fro m w h ich it originates. S p e c ific a lly th e

re lia b ility o f a ciiifcrence score w ill ecpial th e average re lia b ility o f its c o m p o n e n t p arts o n ly w h e n n o c o rre la tio n exists betw een th e tw o scales. A high c o rre la tio n

Thus, the interpretation o f a difference score is p roblem atic through occasions arise

where using them may be relevant. It has been suggested that th e presence o f stro n g

re la tio n s h ip s between p o te n tia l co m p on e nts and a c rite rio n are g enerally a p r io r i

g ro u n d s lo r resisting the c a lc u la tio n o f difference scores (Johns, 1981).

h u r t h er i f difference scores are used th e n tw o caveats a p p ly. F irs t, th e co m p o n e n ts s h o u ld be in te r n a lly consistent m u ltip le -ite m scales and n o t heterogeneous

c o lle c tio n s o f ia c to ria lly in d e ie rm in a n t item s; and secondly, th a t th e re lia b ilitie s o f th e diffe re n ce scores sh o u ld be re p o rte d and c o rre c tio n s f o r a tte n u a tio n p e rfo rm e d . M e th o d o lo g ic a lly the tw o scales c o u ld also be presented at d iffe re n t p o in ts in th e a'i'ic'/.nieni lo rediK c m e m o ry el feel s. I,in le a ile n rio n has been paid to the

p ro b le m a tic c a lc u la tio n ol d iile re n c e scores w it h in the re c ip ro c ity lite ra tu re . A n a lte rn a tiv e m e th o d o f d e fin in g re c ip ro c ity w it h o u t using diffe re n ce scores is to co rre la te the tw o scales m easuring g iv in g and re ce ivin g transactions (N e lso n et ah,

1992). T h e use o f ra tio scores has also been discussed b u t n o t re p o rte d o n (H a tfie ld ,

U tn e , & T ra u p m a n n , 1979).

A second set o f measurement problem s arises fro m the tim e scale o f the measure. 1 he measure o f re c ip ro c ity is usually taken at one p o in t in tim e. It is thus assumed that the decision to act re c ip ro c a lly is based on a m om entary appraisal o f the past

transactions w ith the person being considered.

O n e a cco u n tin g m echanism , proposed b y A n to n u c c i (1990) was th a t o f a s u p p o rt

bank:

people m ay say in specific circum stances, ‘ I am d o in g th is fo r

someone because he o r she p re v io u s ly d id th a t lo r me o r so th a t he o r she w il l do such and such fo r me in th e fu tu re ” .

I t m a y be th a t in d iv id u a ls w h o have a m o re g lo b a l c o n c e p tio n o f th e ir

re la tio n s h ip s w it h specific others (o r a generalized o th e r such as fa m ily ) w i l l be w illin g to p ro v id e fo r others in tim e o f need. T h e assum ption is th a t th e y to o w il l

receive assistance if, and w h e n , th e y are in need (Fischer, 1982). T h e s u p p o rt b a n k

analogy can be taken fu rth e r. T h e c u rre n c y used m ay in fu tu re be subject to

‘in te re s t’ rate changes such th a t the re q u ire d re tu rn becomes h ig h e r o ve r tim e . T h e need to reciprocate as soon as possible, b y n o n -k in , m ay be evidence th a t

indebtedness n o t o n ly is fe lt as u n c o m fo rta b le b u t also th a t th e cost w i l l be h ig h e r la ter. T h e im p o rta n c e o f the su p p o rt b a n k f o r social s u p p o rt th e o ris ts is th a t i t emphasises ih e d y n a m ic nature o f s u p p o rt p ro v is io n o ver tim e . T h e s u p p o rt b a n k

co nce p t can also account fo r the differences betw een c u ltures in re cip ro cal

b e h a v io u r w it h in k in structures (A k iy a m a , A n to n u c c i, & C a m p b e ll, 1990). T h us, in th e measurem ent o l re c ip ro c ity the lim escale o ve r w h ic h re c ip ro c ity is

considered is a s ig n ific a n t facto r.

T h e present thesis, is p io n e e rin g in th a t it is p ro vid e s a th e o ry and a measure o f re c ip ro c ity based on fu n c tio n a l and s tru c tu ra l measures. A s ig n ific a n t a ssum ptio n w it h in th e thesis is th a t re c ip ro c ity is n o t defined as th e actual s u p p o rt resources

exchanged b u t perceived exchange. Evidence f o r perceived re c ip ro c ity is given, in p a rt, fro m the obse rva tio n o f the lo w c o rre la tio n s betw een received s u p p o rt and p syc h o lo g ic a l w e ll-b e in g . T h e question about w h e th e r to measure e xistin g social re la tio n s o r social re la tio n s as perceived b y th e actors in v o lv e d also depends u p o n

(be f()( IIS ol ( be resean b. F o r example, in researcb in ve stig a tin g needle sharing

a m ong in d iv id u a ls tested p o s itiv e fo r H I V / A id s actual social n e tw o rk m e m b e rsh ip

im m e d ia ic “ r e jia y m c iit” w o u ld n o t necessarily o ccur betw een relatives and people w it h lo n g e r te rm re la tio n s h ip expectations (

e.g., Ingersoll-Dayton & Talbott,

1992). A similar finding was reported in a study with college students

(fim g ,1990).

T h e fo llo w in g thesis has tw o m a in objectives. F irs tly , to o u tlin e a th e o ry o f

re c ip ro c ity u sin g a c o g n itiv e representation o f behaving re c ip ro c a lly ; and secondly, to p ro v id e a re lia b le and v a lid measure o f re c ip ro c ity . T h e s tu d y o f re c ip ro c ity is

Chapter 2 Reciprocity: a concept for integrating functional and structural

aspects ol social support

Introduction to reciprocity and social support

'I ’lie p u b lic a tio n o u tp u t o n social s u p p o rt fo llo w s a recognised course in th e

p s y c h o lo g ic a l lite ra tu re . A n in itia l interest in th e area is fo llo w e d b y a focus o n

m easurem ent issues, deve lo p m en t o f conceptual issues, re la tio n s h ip s to outcom es,

th e n a p p lic a tio n to various p o p u la tio n s . A w a n in g in p u b lic a tio n o u tp u t occurs as th e c o m p le x ity o f th e area makes fu rth e r progress m o re d iffic u lt. T h ere th e n

fo llo w s a rediscovery o fte n b y association w ith a n o th e r research area. T h e n e xt step is f o r a n e w in te g ra tiv e conceptual m odel to emerge th a t restarts the p u b lic a tio n cycle.

E vidence f o r such a deve lo p m en ta l course is given b y fig u re 2.1 th a t was p ro d u ce d b y g ra p h in g the n u m b e r o f p ub lis h e d papers c o n ta in in g th e te rm “ social s u p p o rt” in the title by year o i p u b lic a tio n . The data p o in ts arc fro m a lite ra tu re search in th e p s y c lit database and the social sciences c ita tio n index.

T h e d iffe re n tia l decline is, in p art, due to the in te rd is c ip lin a ry research represented b y the social science c ita tio n index, and the m a tu ra tio n o f th e area w it h in the p s y c lit database. A lth o u g h re c ip ro c ity and social s u p p o rt have been lin k e d since

psyclit

soc sel cil

reciprocity

72 74 76

piitjlicaliüfi year

'ig. 2.1 P u b lic a tio n s c o n ta in in g ‘social s u p p o rt’ in th e ir title b y y ea r

K ven w it h th e p r o h lic research a c tiv ity on social s u p p o rt s ig iiiiic a n t questions

re m a in . A n area th a t has n o t been fu lly in v es tig a ted is th e lin k a g e b e tw e e n th e

s tru c tu ra l and lu n c tio n a l aspects ol social support in term s o f b o th t lic o iy and

m e a s u re m e n t. In a m a jo r re v ie w o f th e social s u p p o rt lite ra tu re C o h e n (1985)

c o n c lu d e d th a t social s u p p o rt had a b u ffe rin g effect on stress w h e n measures o f

p erceived a v a ila b ility w e re used, and a d ire ct effect w h e n th e degree o f in te g ra tio n

in a social n e tw o r k was m easured. T h a t c o n c lu s io n has su b s eq u e n tly been

m a in ta in e d in th e lite ra tu re (e.g., A llo w a y & B e b b m g to n , 1987) w it h th e

th e o re tic a l em phasis s tro n g ly fa v o u rin g p erceived ra th e r th a n b e h a v io u ra l

(enacted) social s u p p o rt (I lelgeson, 1993; ITelgeson & C o h e n , 1996).

Social s u p p o rt researchers have c o n s is te n tly em phasised th e need to c la rify th e

lin kag es b e tw e e n s tn ic tu ra l and fu n c tio n a l aspects (B arrera, 1986; B arrera &

A in la y , 1983; C a p la n , 1974; Cassel, 1976; C o b b , 1976; H o u s e & K a h n , 1985;

T h o its , 1995).

F ig u re 2.2 gives representative q u o ta tio n s o ve r a seven year tim escale illu s tra tin g

liie cujjLepUial uveiJ.ip

wcui soci.il ,sii]q)()ri and social nciworks. However,

in v e s tig a tio n o l the s tru c tu ra l and lu n c tio n a l aspects o f social s u p p o rt has been lim ite d b y the use o f research designs th a t correlate o n ly n e tw o rk size (as a p ro x y va ria ble f o r social n e tw o rk stru cture ) and fu n c tio n a l measures developed p r im a r ily

o n th e p o s itiv e receipt o f su p p o rt. F ro m the absence o f a consistent p o s itiv e c o rre la tio n between the tw o co nstructs, it is adduced th a t the re is n o re la tio n s h ip b etw een th e s tru c tu ra l and fu n c tio n a l aspects o f social s u p p o rt.

“ First, ‘social support’ may best be understood as a metaconstruct, referring to three subsidiary constructs:

support network resources, supportive behaviors, and subjective appraisals of support”. (Vaux, Riedel, &

Stewart, 1987 p.209)

“ 1 propose broad categorical classifications of the concepts commonly included under the social support

rubric. Three classes oi support concepts (measures) are proposed: social networks, perceived social support,

and supportive behaviors”. (Cohen, 1992 p.109)

"Social support measures may be divided into three general categories: network measures, measures of

support actually received or reported to have been received, and measures of the degree of support the person

perceives to be available”. (Sarason di.Sarason, 1994 p.43)

F ig u re 2.2 Q u o ta tio n s p ro p o s in g a lin ka ge betw een social s u p p o rt and social n e tw o rk s

T h e tra n s a c tio n a l natu re o f re c ip ro c ity has been id e n tifie d as one k e y m e d ia tin g

va ria ble (A n to n u c c i & Jackson, 1990; A n to n u c c i & John so n, 1994). U n fo r tu n a te ly th e ad hoc m easurement o f re c ip ro c ity w it h in the lite ra tu re has led to lo w

aggregation and g e n e ra lis a b ility o f research fin d in g s . T hus, th e use o f m e ta-an a lytic m e tho d s (R osenthal, 1991; W o lf, 1986) is p rem ature.

A lite ra tu re re vie w o f th e social s u p p o rt lite ra tu re fro m 1976 to th e 1998 id e n tifie d

th e absence. T h e s tu d y characteristics were: a d e fin itio n o f re c ip ro c ity th a t in c lu d e d at least tw o s u p p o rt dim ensions; a scale w it h m o re th a n tw o item s p e r s u p p o rt d im e n s io n ; quo ted p s y c h o m e tric p ro pe rtie s; an e x p lo ra to ry fa c to r

analysis; and c o rre la tio n w ith o th e r k n o w n s u p p o rt re c ip ro c ity measures. T h u s, a value o f fo u r w o u ld represent a s tu d y c o m p a ra tiv e ly h ig h e r th a n a s tu d y w it h a

T a ble 2.1 D e fin itio n s o f R e c ip ro c ity b y year o f stud y

Ikknik(IVVM) iiidcx-^

“Three questions were posed ;ibout instnimental support given, for example, ‘How often did

It oecur in the past \ eai that ) ou lielped the loliowing persons with daily ehoies in and around

the house, such as preparing meals, cleaning the house, transportation, small repairs or filling in

lorrns?’ Three similar questions were asked about the instrumental support received and six

questions were asked abovrt the emotional support given and received. An example of emotional

support given: ‘How often did it occur in the past year that you showed the following people

yoit cared for them?’ The choice of answers was ‘never’, ‘seldom’, ‘sometimes’, and ‘often’ and

they were scored on a scale from one to four. For each relationship a sum score of instrumental

and emotional support received and given was computed; the scores of the four scales ranged

from 3 to 12...The reciprocity variables were constructed by subtracting the support received by

the older adult from the support given. A negative score indicated that the older adult was being

overbenefited by the network member, a score of 0 indicated that giving and receiving were

exactly equal, and a positive score indicated that the older adult overbenefited the network

member” p.64

Jung (1997) Index = 3

“Rather than u.sing the ratings ol the IS.SB, however, I modified it to provide a measure of

balatice of support by asking participants to consider not only the frequency of receipt of each

behavior but also how often they performed each behavior for others. Participants rated each

item on a 3-point scale in terms of whether that behavior was received more thati given (3), giveti

more than received (2), or received and given in equal frequency (1) over the past month.

Separate balance indices were constructed for the four types of support (guidance, tangible,

emotional, and informational ) found in Stokes and Wilsott’s (1984) factor analysis of the ISSB

p .80".

Horwitz (1996) Index = 2

“In this research patients were asked about their contributions to the family member who they

gave the most help to in the seven areas of chores, economic contributions, providing care for

others, companionship, participation in family activities, expressing affection, and giving gifts.

Possible responses of a lot (3), some (2), a little (1), and none (0) are summed to form an index of

( | u r M imis loi I h r .iii;iI\msiik hiiird; Dors i rciju oi il \- rxisi in I hrsr rai egi ving sil uatiniis? What is reciprocity in these situations? How is it manifested? By whom? When does it occur? With what

( onseipieiices?" p.352

Williams (1995) Index =0

“I collected the data on reciprocity from a single open-ended question and any additional field

notes that mentioned reciprocity. Parents were specifically asked ‘Do you ever feel a need to ‘pay

back’ family or friends for their assistance?’ p.404.”

Rinntala (1994) Index =0

“Each paiticipant was asked to name persons whom he or she deemed to be important sources of

iielp, support, and guidance. The participant then rank-ordered this list of persons with regard to

impoMance and indicateil whether each of the five top-ranked supporters was either the

participant’s parent, child, spouse, sibling, other relative, friend, neighbor, fellow club or church

member, or coworker, or was a professional worker. To obtain measures of reciprocity, for each

of the five top-ranked persons, the paiticipant was asked whether the other person helped the

participant more, the participant helped the other person more, or they helped each other

etpially (i.e., reciprocal relationship). The number (maximum of five) of each of these three types

of relationships was calculated for each paiticipant. p.19”.

Dwyer (1994) Index =0

“The primary caregiver was asked about four possible tasks (i.e., household chores, babysitting,

money gilts, keeps caregiver company) that the elder ma)’ provide in the context of the

caregiving relationship. These tasks are summed to create a reciprocity indicator that ranges from

Buuiik (1993) Index =0

The nie;isure of perceived reciprocity in both studies derived from checking one of the following

nnswers nfter considering tiieir rehitionsiiip (e.g., showing iinderstnnding, giving information,

(‘X|)i essiiig ap|)i fi'ia l ion ) w ilh I hen .supcnois (and a d n p h c a le p ro ce d u re w ith colleague.^):

1.1 am providing much more help and support to my superior than 1 receive in return

2. I am providing more help and support than I receive in return

3. We are both providing the same amount of help and support to one another

4. My superior is providing more help and support to me than I provide in return

5. My superior is providing much more help and support to me than I provide in return

The subjects were then divided into three groups: those receiving reciprocity (score 3) those

feeling deprived (scores 1 and 2) and those leeling disadvantaged (scores 4 and 5).

Cordova (1993) Index =0

“Negative reciprocity was defined as the occurrence of aversive behavior on the part of one

pattnet given aveisive behavior b\’ the other p.362"

Walker (1992) Index = 1

“Because it is important to represent a variety of resources in any study of resource exchange, in

this stud)', |ieiceptions of the giving(receiving) of love, information, advice, and money, which

vary in the two fundamental resource properties, were assessed.

The locus ol this study was on the perception ol reciprocity in caregiving. Therefore, research

questions highlighted this caregiving context. Specifically, for each type of aid, mothers were

asked, “Do you feel you give your daughter (type of aid) in return for her helping you?

Responses were coded yes, no, or don’t know. Individuals who answered “no” were not asked

follow-up questions. This procedure should lead to underestimations of aid if other

nonconditional aid also was given.

For each aid type, daughters were asked, “How much (type or aid), if any, do you feel your

mother gives you in rettirn for you helping her? Responses were a great deal, some, not much,

none. We were interested primarily in distinguishing daughters who perceived that they received

aid ill leiiiiii lor I heir help from those who did not. When daughters indicated that “not much”

aid was received, they often indicated that the amount of aid received was very little or almost

none. Therefore, “not much” responses were grouped together with responses of “none” into a

people lo whom \'oii are lelaied eilher b\’ blood or through marriage.

1. In the past six months, how often have you given your affection (a hug, kiss, told them you

love them, or offered advice) to a family member?

1. Never or hardly ever

2. Sometimes

3. Frequently

2. in the past six months, how often have you received affection from a family member?

3. In the past six months, how often have you assisted a family member with household tasks,

babysitting, transportation, or money?

4. In the past six monihs, how often have you received assistance from a family member?

Scale scores ol 1-2 = low reciprocity;

2.25-2.50 = moderate reciprocity ; 2.75-3.00 = high reciprocity

Nelson (1992) Index =3

Four stnge process of data collection:

(1) Residents asked lo n:tine the people who were inipottanr to them with whom they had had

contact over the past nine months categorised as family, friends and professionals;

(2) Residents then asked to describe qualitatively how their relationships had changed over the

past few months in terms of both positive and negative changes;

(3) Residents asked to provide information on the nature of their contacts specifically to identify

the members on their network list who had provided the four types of supportive (emotioiinl,

social, tangible, problem-solving) and unsupportive transactions. For each item scores were

calculated by summing the number of people named in the three network segments.

(4) Frequency of suppoitive and unsupportive transactions provided to and received from

network members. For each of the four types of support, give and received, residents asked to

lair Oil ;t five point scale hftw fiequenily that transaction had occurred over the past month

(1 =not at all to 5= almost every day) scored as averages across network members therefore did

not differentiate between types of network member

Kulis (1992) Index = 1

“Intergenerational patterns of assistance were assessed through five paired questions. First,

parents filled out a chart indicating whether or not each of their adult children regularly did the

following for the parent:

(a) ‘listens to problems and provides advice’;

(b) ‘provides news about mutual friends and the family’;

(c) ‘helps out with household tasks, including transportation’;

(d) provides financial assistance’;

(e) ‘provides compaiiiousliip’. Then the parents indicated whether they, or their spouses,

(1) total reciprocity lor dicltotomous scores

(2) total reciprocity lor raw scores

based on the aggregate sums of the number of reciprocal relationships in any givennetwork

(3) relationship specific

(4) support specific

In order to generate the network list (based on an exchange approach)

20 questions were asked which included the loliowing areas: helping w ith household chores,

talking about personal problems, borrowing a large sum of money, taking care of children,

having coffee or drinks at home.

Onls’ the first 10 names were recorded.

6 questions relerred to emotional support

8 questions to instrumental support

4 questions to social support

2 questions (hobbies and social activities) were not reciprocally scored.

Primomo (1990) Index = 0

Variation on the use of the Norbeck Social Support Questionnaire (Norbeck et al., 1981) with

the addition of one question “the extent to which each network member discussed important

Kirschling (1990) Index =4

Cost -.iiid Reciprocity Jiidex (CRl)

Assessjiieut comprises tliree stages:

1. Subjects identify the people who are important to them and tlieir relationship with the

identified people;

2. Subjects identify the five most important people, the inner network;

3. Subjects respond to 38 likert type questions for each person listed in their inner network

The subscales comprise:

(a) social support (10 items) alpha = .92

(b) reciprocity (9 items) alpha = .86

(c) cost (6 items) alpha = .89

(d) conflict (13 items) alpha = .94

N= 261

items range from ‘not at all’ (0) to a ‘great deal’ (4).

An example ol a reciprocity item is

‘How often do these people come to you for a boost in spirits?’

f i m g (1990) linlrx =2

A modified version of the SSQ (Sarason et ah, 1983) using every other item of the Number Scale

and coding lor boih amount ol support received and also lor how much suppoit was provided

by the respondent. The SSQ(S) was not used.

13 questions were used.

Total support received was calculated as the mean number of support providers named on scale

items. Similarly total support provided was the mean number of people to whom support was

given.

Family and Friends were distinguished for the reciprocity analysis as well as total reciprocity.

A conceptual distinction was made between lenient & stringent measures of reciprocity.

Lenient reciprocity was calculated as the reciprocity over the network of individuals, that is,

summing over the dyadic relationships.

Stringent reciprocity was calculated by only counting the number of exchanges that involved the

same people giving and receiving that lorm ol suppoit to each other summed over the scale

were suinined to create a reciprocits’ indicator (alpba = .43) p.168”

Akiyama (1990) Index = 1

“By the term reciprocity, we reler to equal or comparable exchanges of tangible aid, emotional

affection, advice, or information betvs een individuals or groups. I his limited dehnition is

generally accepted without controverss', referring simply to the notion of exchange, that is,

gn ing and receiving p. 128”.

“The first study was originally conceived as a comparative study of the rules for reciprocal

exchange of six kinds of basic interpersonal resources (money, goods, services, information,

status, and love) in the Japanese family and the American family p.129.”

Antonucci ( 1990) Index = 1

‘Tight I,','.', v.oidd v"ii '..IV V'ui pM/vidcd moic Mipporl, advice, and help to your (spouse,

mot her, fat her, child and f i icnd) in your support net work, is it about equal, or does he/she

provide more to s'ou?” p.323