Impaired Health-Related Quality of Life in Children

With Recurrent Pain

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: Recurrent long-term pain is common in children, but the significance and importance of the problem in a general population context are unclear.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: This study presents novel and important information about associations between HRQoL and recurrent pain in young schoolchildren. It also adds novel information on the effects of the number of pain sites on this association.

abstract

OBJECTIVE:The goal of the current study was to investigate self-reported, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in a general population of young schoolchildren with recurrent pain (ie, headache, stomach-ache, or backache).

METHODS:The study was performed in Umeå, a university city in Swe-den. All children in grades 3 and 6 were invited, and 97% participated (313 girls and 292 boys in grade 3 [mean age: 9.7 years]; 386 girls and 464 boys in grade 6 [mean age: 12.6 years]). Pain and HRQoL were measured with questionnaires.

RESULTS:Two thirds of the children reported recurrent pain (at least monthly). One third reported weekly pain, and 4 of 10 experienced pain from multiple locations. HRQoL impairment was twice as common among children with recurrent pain, compared with children without pain. All aspects of HRQoL (ie, physical, emotional, social, and school functioning and well-being) were impaired. The level of impairment was classified as considerable, especially for children who experi-enced pain from multiple body sites and children with weekly pain (Cohen’sd⫽0.6 – 0.8).

CONCLUSIONS:This study shows that young schoolchildren with re-current pain have considerable impairment of their HRQoL.Pediatrics

2009;124:e759–e767

AUTHORS:Solveig Petersen, PhD,aBruno Lars Ha¨gglo¨f,

PhD,band Erik Ingemar Bergstro¨m, PhDa

Departments ofaClinical Sciences, Pediatrics, andbChild and

Adolescent Psychiatry, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden

KEY WORDS

abdominal pain, back pain, child, headache, quality of life

ABBREVIATIONS

HBSC—Health Behavior in School-aged Children HRQoL— health-related quality of life

PedsQL—Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory OR— odds ratio

CI— confidence interval

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2008-1546 doi:10.1542/peds.2008-1546

Accepted for publication Apr 10, 2009

Address correspondence to Solveig Petersen, PhD, Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Umeå University, Umeå, SE-90187, Sweden. E-mail: solveig.petersen@pediatri.umu.se PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275). Copyright © 2009 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

Recurrent long-term pain has been identified as a common problem in children. Most children with recurrent pain experience pain in the head, stom-ach, or musculoskeletal system,1–3with

pain at⬎1 location being noted for at least one half of the children.2–5

Preva-lence estimates vary, but epidemiolog-ical studies support the occurrence of recurrent or chronic pain in 25% to 35% of the child population,2–4with

in-creasing prevalence over time.6–8

Although pain conditions are common, both the causes and impact in a gen-eral population context are still un-clear. The literature suggests that children with recurrent pain condi-tions may experience general impair-ment of their health-related quality of life (HRQoL).9–13HRQoL is a

comprehen-sive multidimensional concept includ-ing at least physical, emotional, and social dimensions of functioning and well-being, and it has been acknowl-edged as helpful for clinical decision-making as well as health care policy-making.14,15 The core dimensions of

HRQoL may not only expose the impact of pain. Deprived physical, emotional, and social states have been suggested to induce pain experiences by influ-encing pain-processing.16–20

There-fore, the aggregate measure of HRQoL may provide important information related to both the causes and impact of pain. Only a few investigations per-formed standardized HRQoL evalua-tions for children with recurrent pain; those investigations usually did not take into consideration the meaning of cooccurring pain conditions, and they were performed mostly in clini-cal settings that were not representa-tive of the child population in gener-al.9–13,21 In general populations, low

levels of parent-child agreement in pain ratings and low levels of

medi-cal attention-seeking among

chil-dren with recurrent pain have led to

suggestions of low levels of pain-associated impairment.22

The objectives of this study were to ad-dress the following questions. (1) Is there a difference in HRQoL between young schoolchildren with and without recurrent pain conditions (ie, head-ache, stomachhead-ache, or backache)? (2) Does HRQoL differ according to the number of pain sites or pain frequency in young schoolchildren with recur-rent pain? These questions were stud-ied with girls and boys in different age groups. Expectations were for merely trivial differences in HRQoL between children with and without recurrent pain and for lower HRQoL with higher numbers of pain sites or greater fre-quency of pain episodes.

METHODS

Study Population and Procedure

The study was performed in 2003–2004 in Umeå, a university municipality in Sweden with⬃110 000 inhabitants. All schoolchildren in grades 3 and 6 (N⫽

1655) in the city of Umeå were invited, and 97% of the children participated in the study. Children enrolled in special schools for children with intellectual disabilities were not included. Partici-pants were 8 to 14 years of age (mean: 11.3 years) and included 313 girls and 292 boys in grade 3 (range: 8 –11 years; mean: 9.7 years) and 386 girls and 464 boys in grade 6 (range: 12–14 years; mean: 12.6 years).

Before the investigation, pupils, par-ents, and involved school staff mem-bers received information about the study. With instruction by one of the investigators (Dr Petersen) and with the teacher present but not participat-ing, children in grade 6 completed coded pain and HRQoL questionnaires confidentially in the classroom. Chil-dren in grade 3 completed the HRQoL questionnaire in the classroom and the pain questionnaire at home, as-sisted by a parent. Parents completed

a sociodemographic form. Codes were accessible only to the research leader. If necessary, children in grade 6 could listen to the questions on a minidisc; in grade 3, the investigator read the HRQoL questions aloud one by one.

Pain questions were answered by 1495 children, and 1570 children completed the HRQoL questionnaire. Six HRQoL forms were later excluded because of missing items. Both questionnaires were completed adequately by 1455 children (88%), and 1353 of their par-ents (93%) completed the sociodemo-graphic form.

Measures

Pain

Pain was measured with questions from the international, World Health

Organization Health Behavior in

School-aged Children (HBSC) study.23

These questions have shown adequate face validity and test-retest reliability.24

The questions were framed as, “In the past 6 months, how often have you had a headache?” (alternatively, stomach-ache or backstomach-ache), and response al-ternatives were as follows: 1⫽about

every day, 2 ⫽ more than once per

week, 3⫽about every week, 4⫽about every month (referred to as monthly), and 5⫽rarely or never. Categories 1 to 3 together are referred to as weekly or frequent pain and categories 1 to 4 together are referred to as recurrent pain.

Health-Related Quality of Life

The 23-item, Pediatric Quality of Life In-ventory (PedsQL) 4.0 generic core

scale, self-report form measured

HRQoL.25Eight items captured physical

sleep problems, a 5-item social do-main focusing on peer relationships and participation in social activities, and a 5-item school domain address-ing school performance and the ability to be in school.

Recall time was 1 month, and the re-sponse alternatives were as follows: 0⫽never a problem, 1⫽almost never

a problem, 2⫽sometimes a problem,

3⫽often a problem, and 4⫽almost

always a problem. Categories 0 and 1 together are referred to as almost never problems, category 2 is referred to as sometimes problems, and cate-gories 3 and 4 together are referred to as frequent or often/always problems. A HRQoL problem was classified as

present whenⱖ1 item was scored as

ⱖ2 and the problem was considered

frequent whenⱖ1 item was scored as

ⱖ3 (this classification did not include the question of pain in the physical domain). Mean scale scores were

given when ⱖ50% of item scores

were available. For estimation of mean scores, scores were reversed and transformed into a 100-point scale, with higher scores indicating better HRQoL.25

The PedsQL has shown acceptable psy-chometric properties, with discrimi-nating power for recurrent pain condi-tions.11–13,25–27 Within the present

population, reliability and validity were supported.28

Sociodemographic Features

Children reported sex and school grade and, in grade 6, ethnicity and family structure. Parents reported eth-nicity and family structure in grade 3, along with parental employment and education. Parents also reported child long- and short-term ill health, along with child health care contacts dur-ing the preceddur-ing 6 months and the reason for those contacts. Variables

were dichotomized to distinguish

whether both parents were born in

North America/Europe (ethnicity),

whether the parents lived together (family structure), whether the father

and mother each had ⬎9 years of

schooling (education), whether the father and mother each worked full-time or part-full-time (employment), and whether the child had an ill health con-dition other than headache,

stomach-ache, or backache (non–pain ill

health).

Data Analyses

The data were analyzed by using SPSS 11.5 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Descrip-tive statistics were computed for age-and sex-specific pain age-and for HRQoL among children with and without re-current pain. Pearson’s 2 test and

the Mann-Whitney U test for 2

inde-pendent samples tested group differ-ences. Cohen’sdwas used to estimate the magnitude of differences between mean scale scores (impairment). Dif-ferences were regarded as mean-ingful but small at Cohen’sdof 0.20, medium at 0.50, and large at 0.80.29

In multivariate logistic regression

analyses, pain-HRQoL associations

were corrected for sociodemographic

characteristics (the dependent vari-able was the occurrence of⬎1 HRQoL problem, the independent variable was recurrent, multisite, or frequent pain, and covariates were sociodemo-graphic characteristics). Unless stated otherwise, all differences mentioned were significant at the 95% level (P⬍

.05), with 1 exception; for testing of so-ciodemographic factors as potential confounders, the significance level was set atP⬍.10.

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the re-search ethics committee of the Medi-cal Faculty, Umeå University (project 03-352 and 05-152).

RESULTS

Basic Study Characteristics

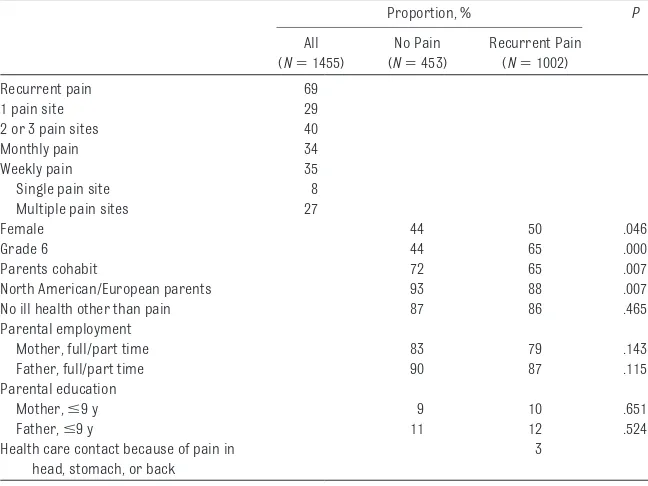

Two thirds of the children reported re-current pain in the head, stomach, or back, and one third experienced pain

ⱖ1 time per week (Table 1). The pain occurred at multiple sites for 4 of 10 children, and the majority of children with weekly pain experienced multisite pain. In comparisons of children with TABLE 1 Basic Study Characteristics

Proportion, % P

All (N⫽1455)

No Pain (N⫽453)

Recurrent Pain (N⫽1002)

Recurrent pain 69

1 pain site 29

2 or 3 pain sites 40

Monthly pain 34

Weekly pain 35

Single pain site 8

Multiple pain sites 27

Female 44 50 .046

Grade 6 44 65 .000

Parents cohabit 72 65 .007

North American/European parents 93 88 .007 No ill health other than pain 87 86 .465 Parental employment

Mother, full/part time 83 79 .143

Father, full/part time 90 87 .115

Parental education

Mother,ⱕ9 y 9 10 .651

Father,ⱕ9 y 11 12 .524

Health care contact because of pain in head, stomach, or back

and without recurrent pain, children with pain more often were in grade 6 and were girls and less often had co-habiting parents or 2 parents of North American or European origin. During the preceding 6 months, 3% of the chil-dren with recurrent pain had been in contact with health care providers be-cause of pain in the head, stomach, or back.

Occurrence of HRQoL Problems

A great majority of children with recur-rent pain reported a HRQoL problem (Table 2). Most of them reported⬎1 HRQoL problem, and the problem oc-curred frequently (often or almost al-ways) for 38%. In comparisons of children with and without a pain con-dition, HRQoL problems were more than twice as common among pain-suffering children, and children with weekly or multisite pain had a four-fold increased risk of HRQoL prob-lems (odds ratio [OR]: 3.7 [95% con-fidence interval [CI]: 2.7–5.0]; data not shown). Adjustment for potential confounders (ie, age, sex, ethnicity, and family structure) resulted in only minor OR changes.

HRQoL Impact According to Pain Characteristics

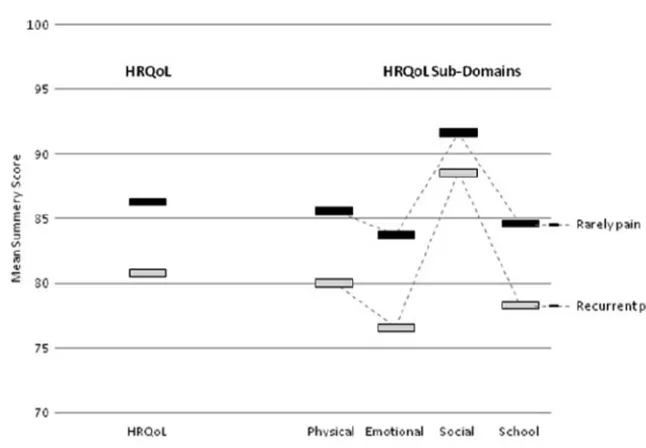

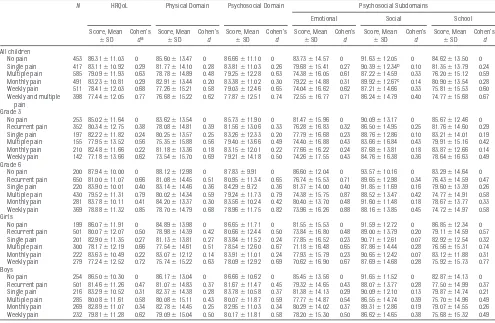

HRQoL mean summary scores were lower (ie, poorer HRQoL) among chil-dren with a pain condition than

among those without a pain condition. Impairment was meaningful across all studied HRQoL domains but was less pronounced in the social domain than in other domains (Fig 1). Impairment also was less pronounced in children with single-site versus multisite pain and in children with monthly versus weekly pain episodes (Table 3). Among children with single-site or monthly pain, the magnitude of impairment was small to medium; among children with multisite or weekly pain, the mag-nitude of impairment was medium to large. Adjustment for age, sex,

ethnic-ity, and family structure resulted in a general decrease of mean scores of

⬃2 points, but differences between

scores for children with versus with-out recurrent pain remained.

Stratification according to pain char-acteristics showed that, regardless of the number of pain sites, the physical scores were lower for children with weekly pain episodes than for chil-dren with monthly pain episodes (Fig 2). In contrast, regardless of pain fre-quency, psychosocial health scores tended to be lower for children with multisite versus single-site pain (the

difference between children with

multisite/monthly pain and children with single-site/weekly pain was not significant).

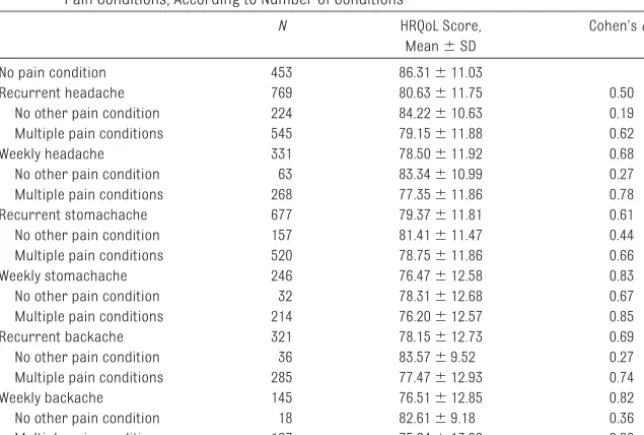

Each pain condition (ie, headache, stomachache, and backache) sepa-rately demonstrated medium to large HRQoL impairment (Table 4). It should be noted that impairment repeatedly was less pronounced for the minority of children for whom the specific con-dition was a single-site pain concon-dition.

FIGURE 1

Comparison of HRQoL between 8- to 14-year old schoolchildren with and without recurrent pain conditions. Cohen’sdspecifies the magnitudes of differences between children who rarely experience pain and children who experience recurrent pain; values of 0.2 are designated as small, 0.5 as medium, and 0.8 as large.

TABLE 2 Comparison of HRQoL Problems for 8- to 14-Year-Old Schoolchildren With or Without Recurrent Pain

HRQoL Problem Prevalence, % OR (95% CI) No Pain

(N⫽453)

Recurrent Pain (N⫽1002)

Crude Adjusteda

Almost never 36.6 19.1 1 1

Sometimes/often/always

ⱖ1 problem 63.4 80.9 2.47 (1.92–3.15) 2.33 (1.80–3.01) Several problems 48.3 68.5 2.72 (2.10–3.52) 2.57 (1.97–3.35) Often/always

Age and Sex Perspectives

The HRQoL impairment described

above was seen in pain-suffering chil-dren in both grades and of both gen-ders (Table 3). Children in grade 6, however, revealed greater impairment than did children in grade 3, which was mainly attributable to more-pronounced impairment of emotional and school scores among children in grade 6. HRQoL levels were generally quite similar for girls and boys but, among children with multisite or weekly pain, grade- and sex-stratified analyses showed greater HRQoL impair-ment among girls than among boys (dif-ference in Cohen’s dofⱖ0.2 for both grades). The most-pronounced HRQoL impairment was seen for girls in grade

6 with multisite or weekly pain (HRQoL

impairment: Cohen’s d ⫽ 0.9 –1.0;

physical impairment: Cohen’sd⫽0.7– 0.8; psychosocial impairment: Cohen’s

d ⫽ 0.9 –1.0; emotional impairment:

Cohen’sd ⫽ 1.1; school impairment:

Cohen’sd⫽0.8).

DISCUSSION

The present study evaluated associa-tions between HRQoL and recurrent pain in a large, population-based sam-ple of young school-aged children. It also investigated relationships be-tween HRQoL and numbers of pain lo-cations. The results show that children with recurrent pain have substantially lower HRQoL than do their peers with no pain condition and multisite pain

is associated with poorer HRQoL than is single-site pain. The lower HRQoL in pain-suffering children is ex-pressed as a higher prevalence of children with HRQoL problems, a higher frequency of HRQoL problem episodes, and a larger number of im-paired HRQoL aspects.

HRQoL impairment was evident within all studied HRQoL aspects, which is consistent with results from studies of adolescents with recurrent pain (nonclinical sample) and younger as well as older school-aged patients with specific pain conditions, that is, headache, abdominal pain, or muscu-loskeletal pain.9,11–13,21,30These results

suggest general HRQoL impairment, in-cluding all core elements of HRQoL in TABLE 3 Comparison of HRQoL Scores Between Schoolchildren Without and With Pain of Different Severities, According to Age and Sex

N HRQoL Physical Domain Psychosocial Domain Psychosocial Subdomains

Emotional Social School

Score, Mean

⫾SD

Cohen’s

da

Score, Mean

⫾SD

Cohen’s

d

Score, Mean

⫾SD

Cohen’s

d

Score, Mean

⫾SD

Cohen’s

d

Score, Mean

⫾SD

Cohen’s

d

Score, Mean

⫾SD

Cohen’s

d

All children

No pain 453 86.31⫾11.03 0 85.60⫾13.47 0 86.66⫾11.10 0 83.73⫾14.57 0 91.63⫾12.05 0 84.62⫾13.50 0 Single pain 417 83.11⫾10.92 0.29 81.77⫾14.10 0.28 83.81⫾11.03 0.26 79.68⫾15.41 0.27 90.39⫾12.34b 0.10 81.35⫾13.79 0.24

Multiple pain 585 79.09⫾11.93 0.63 78.78⫾14.89 0.48 79.25⫾12.28 0.63 74.38⫾16.05 0.61 87.22⫾14.59 0.33 76.20⫾15.12 0.59 Monthly pain 491 83.23⫾10.81 0.29 82.91⫾13.44 0.20 83.38⫾11.02 0.30 79.22⫾14.88 0.31 89.92⫾12.67c 0.14 80.90⫾13.54 0.28

Weekly pain 511 78.41⫾12.03 0.68 77.26⫾15.21 0.58 79.03⫾12.46 0.65 74.04⫾16.62 0.62 87.21⫾14.66 0.33 75.81⫾15.53 0.60 Weekly and multiple

pain

398 77.44⫾12.05 0.77 76.68⫾15.22 0.62 77.87⫾12.51 0.74 72.55⫾16.77 0.71 86.24⫾14.79 0.40 74.77⫾15.68 0.67

Grade 3

No pain 253 85.02⫾11.64 0 83.62⫾13.54 0 85.73⫾11.90 0 81.47⫾15.96 0 90.09⫾13.17 0 85.67⫾12.46 0 Recurrent pain 352 80.34⫾12.75 0.38 78.08⫾14.81 0.39 81.56⫾13.06 0.33 76.28⫾16.83 0.32 86.50⫾14.95 0.25 81.76⫾14.60 0.29 Single pain 197 82.22⫾11.82 0.24 80.25⫾13.57 0.25 83.26⫾12.33 0.20 77.79⫾16.68 0.23 88.76⫾12.86 0.10 83.21⫾14.01 0.19 Multiple pain 155 77.95⫾13.52 0.56 75.35⫾15.88 0.56 79.40⫾13.66 0.49 74.40⫾16.88 0.43 83.66⫾16.84 0.43 79.91⫾15.16 0.42 Monthly pain 210 82.48⫾11.66 0.22 81.18⫾13.36 0.18 83.15⫾12.01 0.22 77.66⫾16.22 0.24 87.68⫾13.81 0.18 83.87⫾12.66 0.14 Weekly pain 142 77.18⫾13.66 0.62 73.54⫾15.70 0.69 79.21⫾14.18 0.50 74.26⫾17.55 0.43 84.76⫾16.38 0.36 78.64⫾16.63 0.49 Grade 6

No pain 200 87.94⫾10.00 0 88.12⫾12.98 0 87.83⫾9.91 0 86.60⫾12.04 0 93.57⫾10.16 0 83.29⫾14.64 0 Recurrent pain 650 81.00⫾11.07 0.66 81.08⫾14.45 0.51 80.95⫾11.34 0.65 76.74⫾15.53 0.71 89.65⫾12.98 0.34 76.43⫾14.59 0.47 Single pain 220 83.90⫾10.01 0.40 83.14⫾14.46 0.36 84.29⫾9.72 0.36 81.37⫾14.00 0.40 91.85⫾11.69 0.16 79.60⫾13.39 0.26 Multiple pain 430 79.52⫾11.31 0.79 80.02⫾14.34 0.59 79.24⫾11.73 0.79 74.38⫾15.75 0.87 88.52⫾13.47 0.42 74.77⫾14.91 0.58 Monthly pain 281 83.78⫾10.11 0.41 84.20⫾13.37 0.30 83.56⫾10.24 0.42 80.40⫾13.70 0.48 91.60⫾11.48 0.18 78.67⫾13.77 0.33 Weekly pain 369 78.88⫾11.32 0.85 78.70⫾14.79 0.68 78.96⫾11.75 0.82 73.96⫾16.26 0.88 88.16⫾13.85 0.45 74.72⫾14.97 0.58 Girls

No pain 199 86.07⫾11.91 0 84.89⫾13.98 0 86.65⫾11.71 0 81.55⫾15.53 0 91.59⫾12.72 0 86.85⫾12.34 0 Recurrent pain 501 80.07⫾12.07 0.50 78.98⫾14.39 0.42 80.66⫾12.44 0.50 73.84⫾16.80 0.48 89.00⫾13.79 0.20 79.11⫾14.59 0.57 Single pain 201 82.90⫾11.35 0.27 81.13⫾13.81 0.27 83.84⫾11.52 0.24 77.85⫾16.52 0.23 90.71⫾12.61 0.07 82.92⫾12.54 0.32 Multiple pain 300 78.17⫾12.19 0.66 77.54⫾14.61 0.51 78.54⫾12.60 0.67 71.18⫾16.48 0.65 87.86⫾14.44 0.28 76.56⫾15.31 0.74 Monthly pain 222 83.63⫾10.49 0.22 83.07⫾12.12 0.14 83.91⫾11.01 0.24 77.93⫾15.79 0.23 90.65⫾12.42 0.07 83.12⫾11.88 0.31 Weekly pain 279 77.24⫾12.52 0.72 75.74⫾15.22 0.63 78.09⫾12.92 0.69 70.62⫾16.90 0.67 87.69⫾14.68 0.28 75.92⫾15.73 0.77 Boys

No pain 254 86.50⫾10.30 0 86.17⫾13.04 0 86.66⫾10.62 0 85.45⫾13.56 0 91.65⫾11.52 0 82.87⫾14.13 0 Recurrent pain 501 81.46⫾11.26 0.47 81.07⫾14.83 0.37 81.67⫾11.47 0.45 79.32⫾14.65 0.43 88.07⫾13.77 0.28 77.50⫾14.99 0.37 Single pain 216 83.29⫾10.52 0.31 82.37⫾14.38 0.28 83.78⫾10.58 0.37 81.38⫾14.13 0.29 90.09⫾12.10 0.13 79.87⫾14.74 0.21 Multiple pain 285 80.08⫾11.61 0.58 80.08⫾15.11 0.43 80.07⫾11.87 0.59 77.77⫾14.87 0.54 86.55⫾14.74 0.39 75.70⫾14.96 0.49 Monthly pain 269 82.89⫾11.07 0.34 82.78⫾14.45 0.25 82.95⫾11.03 0.34 80.29⫾14.02 0.37 89.31⫾12.86 0.19 79.07⫾14.55 0.26 Weekly pain 232 79.81⫾11.28 0.62 79.09⫾15.04 0.50 80.17⫾11.81 0.58 78.20⫾15.30 0.50 86.62⫾14.65 0.38 75.68⫾15.32 0.49

aCohen’sdspecifies the magnitude of differences for children with no pain versus children with pain (recurrent pain, single-site versus multisite pain, and monthly versus weekly pain);

Cohen’sdof 0.2 was considered small, 0.5 medium, and 0.8 large. With the Mann-WhitneyUtest for 2 independent samples,Pwas⬍.001 for all comparisons between the samples with no pain and samples with pain, except as noted.

clinical and nonclinical populations of pain-suffering school-aged children.

The high prevalence of recurrent pain found in the current study is in line with literature findings,2–4 and so is

the lower HRQoL with higher pain fre-quency.31–33 High levels of multisite

pain were also described earlier,2–5

whereas the significance of the

num-ber of pain sites for HRQoL is relatively unexplored. The current findings of greater HRQoL impairment for chil-dren with multisite pain versus single-site pain, however, have some support in a study of adults reporting more HRQoL problems with greater num-bers of pain sites.34Moreover, single

HRQoL aspects (eg, emotional and

functional problems) have been found to increase with greater numbers of pain sites in both adults and chil-dren,35,36and a study monitoring

chil-dren from 4 to 10 years of age found that early behavioral problems were associated more closely with later multisite pain than with later single-site pain.37Multisite pain differs from

single-site pain also with respect to pain frequency and age and sex distri-butions.4Therefore, multisite pain and

single-site pain have a number of dif-ferent attributes.

Impairment in children with a specific pain condition (eg, headache) has been studied conventionally in groups including children with both single-site pain and multisite pain. We found a marked difference in HRQoL between such “all-inclusive” groups of children with a specific type of pain and the sub-group suffering the pain condition as a single-site pain. Therefore, studying impairment with any of these 3 specific pain conditions without taking into consideration cooccurring pain may give an incorrect impression of the de-gree of impairment related directly to the specific pain condition.

HRQoL has been known to vary accord-ing to age and sex in general popula-tions,38 as well as in populations of

children with recurrent pain condi-tions.10,27,31,33,39However, HRQoL

impair-ment according to age or sex was not reported in the studies of pain-suffering children, which makes it dif-ficult to evaluate whether the age- and gender-specific results were pain-related. Our study showed HRQoL im-pairment for both sexes and for both age groups studied, but with greater impairment for older children and in part for girls. Additional research is needed to validate these results.

A notable finding from our study is the level of HRQoL impairment, which con-tradicts our expectations. The PedsQL has no cutoff values for clinically rele-FIGURE 2

HRQoL domain scores for 8- to 14-year-old schoolchildren according to the number of pain sites and pain frequency.

TABLE 4 Comparison of HRQoL Scores for 8- to 14-Year-Old Schoolchildren With or Without Specific Pain Conditions, According to Number of Conditions

N HRQoL Score, Mean⫾SD

Cohen’sda

No pain condition 453 86.31⫾11.03

Recurrent headache 769 80.63⫾11.75 0.50 No other pain condition 224 84.22⫾10.63 0.19 Multiple pain conditions 545 79.15⫾11.88 0.62 Weekly headache 331 78.50⫾11.92 0.68 No other pain condition 63 83.34⫾10.99 0.27 Multiple pain conditions 268 77.35⫾11.86 0.78 Recurrent stomachache 677 79.37⫾11.81 0.61 No other pain condition 157 81.41⫾11.47 0.44 Multiple pain conditions 520 78.75⫾11.86 0.66 Weekly stomachache 246 76.47⫾12.58 0.83 No other pain condition 32 78.31⫾12.68 0.67 Multiple pain conditions 214 76.20⫾12.57 0.85 Recurrent backache 321 78.15⫾12.73 0.69 No other pain condition 36 83.57⫾9.52 0.27 Multiple pain conditions 285 77.47⫾12.93 0.74 Weekly backache 145 76.51⫾12.85 0.82 No other pain condition 18 82.61⫾9.18 0.36 Multiple pain conditions 127 75.64⫾13.08 0.88 aCohen’sdspecifies the magnitude of differences between children with no pain condition and those with headache,

vant HRQoL reductions, but clinical samples of school-aged patients with headache and abdominal pain re-ported medium to large HRQoL impair-ments (Cohen’sd⫽0.5– 0.7).16,18,19The

current population revealed compara-ble HRQoL impairment. Furthermore, according to Cohen’s criteria, HRQoL impairment could be regarded as highly perceptible in the current population-based sample. This finding is worrisome, especially considering the age group studied. Notably, with a few exceptions, the children with pain had received no health care for the pain conditions. The results should be seen in light of studies demonstrating that children with recurrent pain most commonly are misunderstood, disbe-lieved, and neglected when they ex-press their pain to parents and health care personal.40–42 The early school

ages are important years with regard to developmental issues and acquiring basic knowledge and skills needed for the future. HRQoL impairment may in-fluence these processes negatively. Therefore, prevention and treatment in early years seem important.

The current study design does not al-low for conclusions about the causal direction between pain and HRQoL. Previous work suggested that recur-rent pain may result in physical, social, and emotional difficulties20,40,43–45 and

that social, emotional, and physical states may promote pain experienc-es.16–20Theoretically, there may be an

interactive loop between recurrent pain and the core elements of HRQoL (ie, physical, emotional, and social functioning and well-being). This sug-gestion is supported empirically in the present study, giving evidence of

asso-ciations between recurrent pain and all of these HRQoL elements. One impli-cation of a bidirectional relationship would be that pain prevention and treatment might benefit from a HRQoL focus. For instance, systematic efforts to secure high HRQoL in the general child population (eg, through school programs aiming at optimizing physi-cal, emotional, social, or school func-tioning and well-being) may have a protective role regarding recurrent pain development and, for children who are experiencing recurrent pain, treatment focusing on improvement in deprived HRQoL aspects may decrease pain experiences. Additional studies are needed to test these hypotheses.

The HBSC study questions used in this study have been demonstrated to be valid for eliciting information on recur-rent pain among schoolchildren.46

Ask-ing about monthly or weekly pain over a 6-month period presumably ex-cluded low-intensity pain and pain at-tributable to insignificant everyday scrapes. The long recall period poses problems at younger ages, however, which is why parents were asked to help younger children recall pain epi-sodes. The influence of this, as well as the influence of different recall peri-ods for the HBSC study (6 months) and PedsQL (1 month) questions, is not known. A drawback of the study is that the PedsQL does not reflect family re-lationships, which are significant for pediatric HRQoL.47

The rather large sample size and high participation rate ensure that the re-sults can be considered representa-tive of young schoolchildren in Umeå. Because the Swedish population is quite homogeneous and Umeå reflects

the Swedish population in several ways (ie, similar family income stan-dard and family structure),48it can be

suggested that the results can be gen-eralized to young schoolchildren, at least in Sweden.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study confirm that recurrent pain conditions are com-mon acom-mong young schoolchildren and, furthermore, that schoolchildren with recurrent pain have considerable im-pairment of their HRQoL, at a level com-parable to that reported for children attending specialist clinics. We also

show that HRQoL impairment is

greater for children with multisite or frequent pain. The results indicate that recurrent pain conditions in young children in general should be re-garded as significant health problem, prompting early interventions. Long-term studies are needed for a full un-derstanding of the natural history of and interplay between recurrent pain and HRQoL, as well as the potential for prevention and treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported finan-cially by the Vårdal Foundation, the County Council of Va¨sterbotten, Queen Silvia’s Jubilee Fund, and the Oscar Foundation.

We thank all participating children, parents, and school staff members. Their great engagement and patience contributed significantly to this study. We also thank Dr Hans Stenlund, stat-istician at the Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine, for statis-tical support.

REFERENCES

1. Goodman JE, McGrath PJ. The epidemiology of pain in children and adolescents: a review.Pain.

1991;46(3):247–264

3. Roth-Isigkeit A, Thyen U, Raspe HH, Stoven H, Schmucker P. Reports of pain among German children and adolescents: an epidemiological study. Acta Paediatr. 2004;93(2):258 – 263

4. Petersen S, Brulin C, Bergstrom E. Recurrent pain symptoms in young schoolchildren are often multiple.Pain.2006;121(1–2):145–150

5. Kristja´nsdo´ttir G. Prevalence of pain combinations and overall pain: a study of headache, stomach pain and back pain among school-children.Scand J Soc Med.1997;25(1):58 – 63

6. Santalahti P, Aromaa M, Sourander A, Helenius H, Piha J. Have there been changes in children’s psychosomatic symptoms? A 10-year comparison from Finland.Pediatrics.2005;115(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/115/4/e434

7. Bandell-Hoekstra IE, Abu-Saad HH, Passchier J, Frederiks CM, Feron FJ, Knipschild P. Prevalence and characteristics of headache in Dutch schoolchildren.Eur J Pain.2001;5(2):145–153 8. Sillanpa¨a¨ M, Anttila P. Increasing prevalence of headache in 7-year-old schoolchildren.Headache.

1996;36(8):466 – 470

9. Powers SW, Patton SR, Hommel KA, Hershey AD. Quality of life in childhood migraines: clinical impact and comparison to other chronic illnesses.Pediatrics. 2003;112(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/112/1/e1

10. Nodari E, Battistella PA, Naccarella C, Vidi M. Quality of life in young Italian patients with primary headache.Headache.2002;42(4):268 –274

11. Youssef NN, Murphy TG, Langseder AL, Rosh JR. Quality of life for children with functional abdom-inal pain: a comparison study of patients’ and parents’ perceptions.Pediatrics.2006;117(1):54 –59 12. Varni JW, Lane MM, Burwinkle TM, et al. Health-related quality of life in pediatric patients with

irritable bowel syndrome: a comparative analysis.J Dev Behav Pediatr.2006;27(6):451– 458 13. Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Limbers CA, Szer IS. The PedsQL as a patient-reported outcome in children

and adolescents with fibromyalgia: an analysis of OMERACT domains.Health Qual Life Outcomes.

2007;5(Feb):9

14. Koot HM. The study of quality of life: concept and methods. In: Koot H, Wallander JL, eds.Quality of Life in Child and Adolescent Illness: Concepts, Methods and Findings. East Essex, UK: Brunner-Routledge; 2001:3–20

15. Eiser C, Morse R. Quality-of-life measures in chronic diseases of childhood.Health Technol Assess.

2001;5(4):1–157

16. Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: a new theory.Science.1965;150(699):971–979

17. Melzack R. Evolution of the neuromatrix theory of pain: the Prithvi Raj Lecture: presented at the Third World Congress of World Institute of Pain, Barcelona 2004.Pain Pract.2005;5(2):85–94 18. Koltyn KF. Analgesia following exercise: a review.Sports Med.2000;29(2):85–98

19. Mathes WF, Kanarek RB. Chronic running wheel activity attenuates the antinociceptive actions of morphine and morphine-6-glucouronide administration into the periaqueductal gray in rats.

Pharmacol Biochem Behav.2006;83(4):578 –584

20. Eisenberger NI, Jarcho JM, Lieberman MD, Naliboff BD. An experimental study of shared sensitivity to physical pain and social rejection.Pain.2006;126(1–3):132–138

21. Langeveld JH, Koot HM, Loonen MC, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AA, Passchier J. A quality of life instrument for adolescents with chronic headache.Cephalalgia.1996;16(3):183–196

22. Balague´ F, Dudler J, Nordin M. Low-back pain in children.Lancet.2003;361(9367):1403–1404 23. Currie C, Roberts C, Morgan A, et al, eds.Young People’s Health in Context: Health Behaviour in

School-aged Children (HBSC) Study: International Report From the 2001/2002 Survey. Copenha-gen, Denmark: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2004. Health Policy for Children and Adolescents Report 4

24. Haugland S, Wold B. Subjective health complaints in adolescence: reliability and validity of survey methods.J Adolesc.2001;24(5):611– 624

25. Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations.Med Care.2001;39(8): 800 – 812

26. Varni JW, Seid M, Rode CA. The PedsQL: measurement model for the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory.Med Care.1999;37(2):126 –139

27. Powers SW, Patton SR, Hommel KA, Hershey AD. Quality of life in paediatric migraine: character-ization of age-related effects using PedsQL 4.0.Cephalalgia.2004;24(2):120 –127

28. Petersen S.Recurrent Pain and Health-Related Quality of Life in Young Schoolchildren[doctoral thesis]. Umeå, Sweden: Umeå University; 2008

30. Merlijn VP, Hunfeld JA, van der Wouden JC, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AA, Koes BW, Passchier J. Psychosocial factors associated with chronic pain in adolescents.Pain.2003;101(1–2):33– 43 31. Hunfeld JA, Perquin CW, Duivenvoorden HJ, et al. Chronic pain and its impact on quality of life in

adolescents and their families.J Pediatr Psychol.2001;26(3):145–153

32. Frare M, Axia G, Battistella PA. Quality of life, coping strategies, and family routines in children with headache.Headache.2002;42(10):953–962

33. Langeveld JH, Koot HM, Passchier J. Headache intensity and quality of life in adolescents: how are changes in headache intensity in adolescents related to changes in experienced quality of life?

Headache.1997;37(1):37– 42

34. Bergman S, Jacobsson LT, Herrstrom P, Petersson IF. Health status as measured by SF-36 reflects changes and predicts outcome in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a 3-year follow up study in the general population.Pain.2004;108(1–2):115–123

35. Gureje O, Von Korff M, Kola L, et al. The relation between multiple pains and mental disorders: results from the World Mental Health Surveys.Pain.2008;135(1–2):82–91

36. Bruusgaard P, Smedbråten B, Natvig B, Bruusgaard D. Physical activity and bodily pain in children [in Norwegian].Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen.2000;120(26):3173–3175

37. Borge AI, Nordhagen R. Development of stomach-ache and headache during middle childhood: co-occurrence and psychosocial risk factors.Acta Paediatr.1995;84(7):795– 802

38. Bisegger C, Cloetta B, von Rueden U, Abel T, Ravens-Sieberer U. Health-related quality of life: gender differences in childhood and adolescence.Soz Praventivmed.2005;50(5):281–291 39. Konijnenberg AY, Uiterwaal CS, Kimpen JL, van der Hoeven J, Buitelaar JK, de Graeff-Meeder ER.

Children with unexplained chronic pain: substantial impairment in everyday life.Arch Dis Child.

2005;90(7):680 – 686

40. Josephson I, Oldfors-Engstrom L. Pain experiences in girls with idiopathic musculoskeletal pain [in Swedish].Nord Fysiother.2004;8:12–18

41. Dell’Api M, Rennick JE, Rosmus C. Childhood chronic pain and health care professional interactions: shaping the chronic pain experiences of children.J Child Health Care.2007;11(4): 269 –286

42. Carter B. Chronic pain in childhood and the medical encounter: professional ventriloquism and hidden voices.Qual Health Res.2002;12(1):28 – 41

43. Hunfeld JA, Perquin CW, Bertina W, et al. Stability of pain parameters and pain-related quality of life in adolescents with persistent pain: a three-year follow-up.Clin J Pain.2002;18(2):99 –106 44. Smedbråten BK, Natvig B, Rutle O, Bruusgaard D. Self-reported bodily pain in schoolchildren.

Scand J Rheumatol.1998;27(4):273–276

45. Brattberg G, Wickman V. Backache and headache are common among school children [in Swed-ish].Lakartidningen.1991;88(23):2155–2157

46. Laurell K, Larsson B, Eeg-Olofsson O. Headache in schoolchildren: agreement between different sources of information.Cephalalgia.2003;23(6):420 – 428

47. Detmar SB, Bruil J, Ravens-Sieberer U, Gosch A, Bisegger C. The use of focus groups in the development of the Kidscreen HRQL questionnaire.Qual Life Res.2006;15(8):1345–1353 48. Statistics Sweden. Yearly statistics about children and their families. Available at: www.scb.se/

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-1546 originally published online September 7, 2009;

2009;124;e759

Pediatrics

Solveig Petersen, Bruno Lars Hägglöf and Erik Ingemar Bergström

Impaired Health-Related Quality of Life in Children With Recurrent Pain

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/124/4/e759 including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/124/4/e759#BIBL This article cites 40 articles, 3 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

edicine_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/anesthesiology:pain_m

Anesthesiology/Pain Medicine

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-1546 originally published online September 7, 2009;

2009;124;e759

Pediatrics

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/124/4/e759

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.