Ethnicity-Related Variation in Sexual Promiscuity, Relationship

Status, and Testosterone Levels in Men

Dario Maestripieri, Amanda Klimczuk, Daniel Traficonte, and M. Claire Wilson The University of Chicago

The purpose of this study was to investigate potential ethnicity-related variation in men’s relationship status, sexual promiscuity, and testosterone levels. Data from two ethnically diverse subject populations were used. The first dataset included 302 male graduate students (age range: 23–36 years;M⫽28); the second dataset consisted of 77 male undergraduate and graduate students (age range: 18 –38 years;M⫽23). For both, we collected information on ethnicity (European American, African American, His-panic, or Asian American), relationship status (single, in a short-term or long-term relationship, or married), and sexual promiscuity (number of lifetime sexual partners, number of one-night stands, extrapair sexual activity), in addition to measuring salivary testosterone concentrations. In both datasets testosterone levels were significantly higher in single men than in men in relationships but this difference was reversed in men of Asian American ethnicity. Asian American men had the lowest number of sexual partners, one-night stands, and extrapair sexual activity across ethnic groups. Moreover, among Asian Americans, men in relationships had a higher average number of sexual partners than single men. Our results indicate that to understand the associ-ation between relassoci-ationship status and testosterone levels in men, ethnicity-related variation in sexual activity in single men and men in relationships must be taken into consideration.

Keywords:relationship status, testosterone, ethnicity, sexual behavior

In humans and many other animal species, testosterone plays a key role in male mating-related competition for status and resources and in male courtship and sexual behavior (e.g.,

Nelson, 2011). In particular, because testoster-one is expected to be elevated when males en-gage in competition with other males as well as during courtship and mating, but low when males are monogamously paired and engaged in parental behavior (e.g., Wingfield, Hegner, Dufty, & Ball, 1990), understanding interindi-vidual and intraindiinterindi-vidual variation in male tes-tosterone levels can provide insight into male mating and parenting effort, which are key as-pects of male life history (e.g.,Bribiescas, 2006).

A growing number of human studies have investigated variation in testosterone levels in relation to relationship/marital status and mat-ing and parentmat-ing effort. Two of the most con-sistent findings that have emerged from this body of research are that single men have higher testosterone levels than men in relationships, and that testosterone levels are particularly low in married men with young children (e.g.,Booth & Dabbs, 1993;Burnham et al., 2003;Gray et

al., 2004; van Anders, Hamilton, & Watson,

2007;van Anders & Watson, 2006; seeGray &

Campbell, 2009, for a review). These

correla-tions between testosterone levels and relation-ship, marital, and parental status, however, are open to different interpretations. First, it is pos-sible that there is no direct causal relationship between testosterone levels and relationship sta-tus but that these variables are independently correlated with a third variable (e.g., a person-ality trait). Second, it is possible that a causal relationship exists such that high testosterone induces males to remain single and low testos-terone induces males to form monogamous repro-Dario Maestripieri, Amanda Klimczuk, Daniel

Trafi-conte, and M. Claire Wilson, Institute for Mind and Biol-ogy, The University of Chicago.

Correspondence concerning this article should be ad-dressed to Dario Maestripieri, The University of Chicago, 5730 S. Woodlawn Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637. E-mail: dario@uchicago.edu This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 96

ductive relationships and to invest in children. Third, it is possible that being single raises a male’s level of testosterone while being in a monogamous relationship and investing in chil-dren lowers testosterone. Clearly, understand-ing if and how relationship status and testoster-one are causally related is crucial for understanding human male social and reproduc-tive strategies, and more generally the evolution of male life history traits.

So far, most evidence seems to support the hypothesis that a causal association exists and that relationship status affects testosterone lev-els rather than the other way around. Some of this evidence comes from longitudinal studies reporting a decrease in men’s testosterone with the transition to fatherhood (e.g., Berg, &

Wynne-Edwards, 2001;Gettler, McDade,

Fera-nil, & Kuzawa, 2011; Hirschenhauser et al., 2002;Kuzawa, Gettler, Muller, McDade, & Fe-ranil, 2009; Perini, Ditzen, Fischbacher, &

Ehlert, 2012; Storey, Walsh, Quinton, &

Wynne-Edwards, 2000); the mechanisms

re-sponsible for the reduction in testosterone could be reduced frequency of sexual intercourse (e.g.,Gettler, McDade, Agustin, Feranil, &

Ku-zawa, 2013), exposure to frequent infant cries

(Fleming, Corter, Stallings, & Steiner, 2002;

Muller, Marlowe, Bugumba, & Ellison, 2009;

van Anders, Tolman, & Volling, 2012),

ex-tended bodily contact with infants through cosleeping (Gettler, McKenna, McDade,

Agus-tin, & Kuzawa, 2012), or simply significant

involvement in caregiving (e.g., Jasienska, Jasienski, & Ellison, 2012).

One possible explanation for high testoster-one levels in single men is that they are, on average, more involved in courtship of multiple potential sexual partners than men in stable monogamous relationships; in turn, interaction with multiple (potential) sexual partners or sim-ply the desire for a high variety of sexual part-ners is known to raise a man’s testosterone (e.g.,

van Anders, Hamilton, & Watson, 2007; van

Anders & Goldey, 2010; Roney, Mahler, &

Maestripieri, 2003; Roney, Lukaszewski, &

Simmons, 2007). For example, polygynously

married Kenyan Swahili men exhibit higher tes-tosterone levels than monogamously married men (Gray, 2003), polyamorous North Ameri-can men have higher testosterone levels than partnered and even single men (van Anders et al., 2007), and testosterone levels are higher in

monogamous men who engage in frequent ex-trapair sexual fantasies and encounters than in those who do not (McIntyre et al., 2006).

In this study, we further investigated the as-sociation between relationship status, sexual promiscuity (defined as desire for or interaction with multiple sexual partners), and male testos-terone levels. To this end, we investigated not only differences between single men and men in relationships but also variation within each group. Our working hypothesis was that, just as the category of paired men is heterogeneous and includes both men who desire or engage in extramarital sexual activities and those who don’t, the single men category is probably het-erogeneous as well and includes both highly sexually active men (e.g., men who are single by choice in order to maximize their opportu-nities to engage in promiscuous sex) and less sexually active men (e.g., men who are single by choice to avoid sexual relationships alto-gether and focus on other aspects of their lives as well as men who are single by constraint, because they are unable to find a partner).

One source of variation in attitudes about being single and sexually promiscuous or in a faithful/unfaithful monogamous relationship is cultural norms concerning men’s sexual re-straint and relationship models in different eth-nic groups or societies (Gray & Campbell, 2009). For example, studies comparing differ-ent ethnic groups in North America have indi-cated that Asian American males exhibit greater sexual conservatism and less sexual experience than men in other ethnic groups (Meston, Trap-nell, & Gorzalka, 1996;Okazaki, 2002).

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that ethnicity-related variation in sexual promiscuity could potentially affect both the magnitude and the direction of the relationship between testos-terone and relationship status: specifically, we predicted that Asian American males should be less sexually promiscuous than males in other ethnic groups, and that the previously reported difference in testosterone between single and paired men should not occur among Asian Americans or be significantly smaller in this group than in other ethnic groups. To test our hypotheses, we first investigated the relation-ship between ethnicity, relationrelation-ship status, and testosterone in a historical database established in 2008. Then we investigated the potential role of sexual promiscuity in a new study conducted

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

in 2013, which involved a smaller sample size but more detailed measures of sexual promiscu-ity. To our knowledge, this study is the first investigation of the role of ethnicity in the as-sociation between men’s relationship status, sexual behavior, and testosterone levels. The study of human mating strategies has increas-ingly incorporated physiological, social, and cultural variables and examined not only be-tween-sex but also within-sex variation. There-fore, this study enhances our knowledge of the social and cultural context for within-sex vari-ation in male mating strategies as well as our knowledge of the relationship between mating effort and testosterone in male life histories.

Method 2008 Dataset

Study participants were 325 male MBA stu-dents in a private midwestern university. These individuals were part of a larger dataset that included a total of 348 males and 153 females. Data from females were not considered in this study. Data from 23 male subjects were not included because information about some of the variables of interest in this study (see below) was incomplete or missing. These individuals were recruited in 2008 to participate in a study of financial risk-taking and stress reactivity (Maestripieri, Baran, Sapienza, & Zingales,

2010; Sapienza, Zingales, & Maestripieri,

2009). Participation in the study was a course requirement therefore it was mandatory for the entire 2008 cohort of MBA students. Students, however, were paid $20 or more for their par-ticipation. The use of human subjects was ap-proved by the IRB and all students were asked for informed written consent for their participa-tion in the study.

Study participants filled out a questionnaire in which they provided information about their age, ethnicity (participants were given a list of ethnicities and asked to choose the one with which they identified; individuals with multiple ethnicities were asked to identify a primary one), and relationship status (single or in a relationship). The survey also included ques-tions about sexual orientation and number of lifetime sexual partners but answering these two questions was not mandatory and many partic-ipants did not answer them. The particpartic-ipants

took a 1-hr computerized test and gave two saliva samples, one before and one after the test. All saliva samples were collected between 1:30 p.m. and 5:00 p.m. (time of sample collection did not significantly affect testosterone levels). Participants were asked not to eat any food, drink anything other than water, or smoke for at least 1 hr prior to the study. Saliva samples were assayed for testosterone concentrations (see

Maestripieri et al., 2010;Sapienza et al., 2009; for details on sample collection and hormonal assays). The means of the testosterone concen-trations of the two samples were used for data analyses.

Mean age (⫾ SE) of the 325 study partici-pants was 28.75 (⫾0.12) years; age range was 23–36 years. Ethnicity and relationship status were distributed as follows: 160 European American (the terms European American and Caucasian are used interchangeably in this arti-cle; single ⫽ 100; in relationship ⫽ 60); 25 African American (for brevity, referred to as African; single ⫽ 20; in relationship⫽ 5); 30 Hispanic American (for brevity, referred to as Hispanic; single⫽12; in relationship⫽18); 50 Far East Asian American (for brevity, referred to as FE Asian; single⫽26; in relationship⫽ 24); 60 Indian American (for brevity, referred to as Indian; single⫽ 30; in relationship ⫽ 30). Each ethnic group included both people born in foreign countries and people born in the U.S.A. (e.g., the FE Asian category included both men born in China and Japan and Chinese American and Japanese American men born in the U.S.A.). Indians included both people born in India or Bangladesh and people born in the U.S.A., with family origins in India or Bangladesh. There were no significant differences in age or rela-tionship status among the five ethnic groups.

2013 Dataset

Study participants were 77 male young adults. Approximately 80% of the study partic-ipants were undergraduate or graduate students (but there were no MBA students among them) at the same university where the 2008 study was conducted, and most of the others were em-ployed by this university under various capaci-ties (e.g., research or administrative staff). Par-ticipants were part of a larger study that also included 75 female participants but female data were not considered in this study. Study

partic-This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

ipants were recruited in 2013 through fliers posted on campus, mailing lists, or a human subject recruitment Web site (Sona System). All study participants completed a written informed consent form before participating in the study and were paid $ 20 after completion of the procedures. The use of human subjects was approved by the IRB.

Study participants were asked to provide a saliva sample and to complete a series of ques-tionnaires online or on paper. Saliva samples were collected and stored in ice using the same procedures used for the 2008 study (e.g., all samples were collected in the early afternoon and time of sample collection did not affect testosterone levels). Samples were later shipped to the Hominoid Reproductive Ecology Labo-ratory at the University of New Mexico, where they were assayed for testosterone, using the Salimetrics salivary testosterone ELISA (Cata-log 1–2402, Salimetrics, LLC, State College, PA). The sensitivity of this assay is approxi-mately 1 pg/ml. The antibody has significant cross-reactivities with dihydrotestosterone (36%) and 19-nortestosterone (21%), neither of which is expected in appreciable quantities in the saliva of healthy adults. All other cross-reactivities are⬍2%. Interassay coefficients of variation (N ⫽ 6) were 5% for a high sample and 14% for a low sample. Intraassay CV (mean CV of duplicates) was 3%. Testosterone data were available for only 62 of the 77 study participants.

An initial demographic survey asked infor-mation about participants’ age, ethnicity (as-sessed with the same procedure used for the 2008 dataset), sexual orientation, and relation-ship status (single or in a relationrelation-ship; for some data analyses, the relationship category was di-vided into subgroups; see below). The other questionnaires asked questions about personal-ity characteristics and romantic and sexual ex-perience and preferences. For the purposes of this study, four questionnaire items were used: (a) the total number of partners with whom study participants had engaged in vaginal, anal, or oral sex over the lifetime; (b) the total num-ber of one-night stands the study participants had had in their lifetime; (c) the total number of partners with whom they had had extrapair sex in their lifetime; and (d) the frequency of fan-tasizing about having extrapair sex (on a scale from 1 ⫽ Never, to 8⫽ at least once a day).

Data for items (c) and (d) were analyzed only for participants who were in a relationship at the time the study was conducted.

Mean age (⫾SE) of the 77 participants was 23.17 (⫾0.50) years; age range was 18 –38 years. Ethnicity and relationship status were distributed as follows: 42 European American (i.e., Cauca-sian; single ⫽ 8; in relationship ⫽ 34); eight African (single ⫽ 4; in relationship ⫽ 4); 14 Hispanic (single⫽ 6; in relationship⫽ 8); 13 Asian (single ⫽ 6; in relationship ⫽ 7; this category included eight East Asian and five Indian men; data analyses provided similar re-sults whether the five Indian men were included in the Asian group or excluded; therefore they were included to increase sample size). As was the case for the 2008 database, each ethnic group included both people born in foreign countries and people born in the U.S.A. There were no significant differences in age or rela-tionship status among the four ethnic groups. Sixty-eight participants self-described their sex-ual orientation as heterosexsex-ual or mainly het-erosexual, seven as homosexual or mainly ho-mosexual, and two as bisexual.

Results 2008 Dataset

A two-way ANOVA examining the effects of ethnic group and relationship status on testos-terone concentrations revealed both a main ef-fect of relationship status, F(1, 315) ⫽ 4.16, (p⬍ .05), with single men having higher tes-tosterone than men in relationships, and a sig-nificant interaction between relationship status and ethnicity,F(4, 315)⫽ 2.40, (p⫽ .05). As

Figure 1a illustrates, among Caucasians,

Afri-cans, and Hispanics, single men had signifi-cantly higher testosterone than men in relation-ships (all p ⬍ .05). Among Indians this difference was much smaller and nonsignifi-cant, and Far East Asians showed a significant difference in the opposite direction: single men had lower testosterone than men in relationships (p⬍.05). There was no significant main effect of ethnicity on testosterone concentrations.

2013 Dataset

Figure 1bdepicts testosterone concentrations in Caucasian, African, Hispanic, and Asian men

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Figure 1. (a). Mean (⫹SE) testosterone levels in single men and men in relationships in five different ethnic groups. Data are from the 2008 dataset. Sample sizes were as follows: 160 Caucasian (single⫽100; in relationship⫽60); 25 African (single⫽20; in relationship⫽ 5); 30 Hispanic (single⫽12; in relationship⫽18); 50 Far East Asian (single⫽26; in relationship ⫽ 24); 60 Indian (single ⫽ 30; in relationship⫽ 30). (b). Mean (⫹ SE) testosterone levels in single men and men in relationships in four different ethnic groups (for brevity, European American is labeled Caucasian, African American is African, Hispanic American is Hispanic, and Asian American is Asian). Data are from the 2013 dataset. Sample sizes were as follows: 34 Caucasian (single⫽4; in a relationship⫽30); eight African (single⫽2; in a relationship⫽6); 10 Hispanic (single⫽5; in a relationship⫽5); 10 Asian (single⫽5; in a relationship⫽5). This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

who were single or in a relationship. A two-way ANOVA revealed a significant interaction be-tween relationship status and ethnicity, F(3, 54)⫽4.84, (p⫽.004). The pattern was similar to that observed in the 2008 dataset: among Caucasians, Africans and Hispanics, single men had higher testosterone than men in relation-ships. The opposite was true among Asians. The differences were statistically significant for Caucasians (t ⫽ ⫺3.2; df ⫽ 32; p ⬍ .01), Hispanics (t ⫽ ⫺3.11; df ⫽ 8; p⫽ .01), and Asians (t⫽ ⫺3.02;df⫽8;p⬍.05) but not for Africans (t ⫽ ⫺0.7; df ⫽ 6; NS), probably because of the small sample size (only two African men were single).

Figure 1b shows that Asian single men had,

on average, the lowest testosterone levels among all single men, and Asian men in rela-tionships had, on average, the highest testoster-one levels of all men in relationships. Variation in testosterone among the single men in the four ethnic groups was statistically significant, F(2, 15)⫽4.91, (p⫽ .01). Post hoc tests indicated that Asian single men had significantly lower testosterone than both Caucasian (p⬍.05) and Hispanic single men (p⬍ .05). Asian men had lower testosterone than African single men (n⫽ 2) as well but the difference was not significant, probably due to the small sample size for this comparison. Variation in testosterone levels among the men in relationships in the four eth-nic groups was not statistically significant,F(3, 45)⫽1.55; NS.

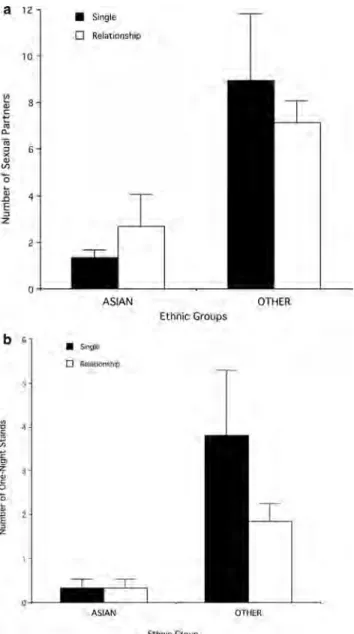

Figure 2adepicts the number of lifetime sex-ual partners for Asian men who were single and in relationships and for men who were single and in relationships in the other ethnic groups (Caucasian, African, and Hispanic) combined. Asian men, regardless of relationship status, had a significantly lower number of sexual partners than the other men,F(1, 72)⫽6.19, (p⫽.01). Among Asians, men in relationships had a higher average number of sexual partners than single men, whereas the opposite was true for men in the other ethnic groups. The statistical interaction between ethnic group and relation-ship status, however, was not significant.Figure 2bshows the total number of one-night stands in Asian men and men from the other ethnic groups, separately for single men and men in relationships. Asian men had significantly fewer one-night stands than other men, regardless of relationship status,F(1, 72)⫽4.86, (p⫽.03).

Of the men who were in relationships, Asian men reported that they had never had extrapair sex in their lifetime, and the others reported that they had had on average approximately one episode (0.81 ⫹0.33) of extrapair sex in their lifetime. Asian men in relationships also fanta-sized about extrapair sex, on average, less fre-quently (3.33⫹1.2) than other men in relation-ships (4.47 ⫹ 0.29). Neither the difference in extrapair sex nor the difference in extrapair sex fantasy, however, was statistically significant (Extrapair sex: t ⫽ ⫺0.87; df ⫽ 52; NS; Ex-trapair sex fantasy:t ⫽ ⫺1.25; df⫽ 48; NS). Testosterone was not significantly correlated with lifetime number of sexual partners (r ⫽ .07;n⫽61; NS), lifetime number of one-night stands (r⫽ .03;n⫽61; NS), lifetime number of extrapair sex events (r⫽.06;n⫽45; NS), or frequency of extrapair sex fantasies (r ⫽ .02; n⫽ 41; NS).

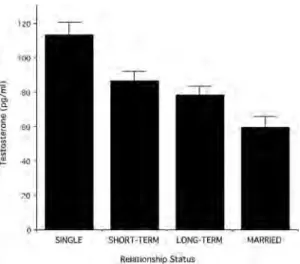

In the next set of analyses, testosterone data for Caucasians, Africans, and Hispanics were pooled together and men in relationships were subdivided into three categories depending on whether they were in short-term (less than 6 months) relationships, in long-term (more than 6 months) relationships, or married. Figure 3

illustrates the testosterone data for men in these relationship categories along with data for sin-gle men. A one-way ANOVA revealed a signif-icant difference in testosterone concentrations among the four groups,F(3, 51)⫽10.54, (p⬍ .0001). Bonferroni-Dunn post hoc tests indi-cated that single men had higher testosterone than men in the other three groups (allp⬍.05), married men had lower concentrations than men in the other three groups (allp⬍.05), and men in short-term relationships had higher concen-trations than men in long-term relationships (p⬍ .05).

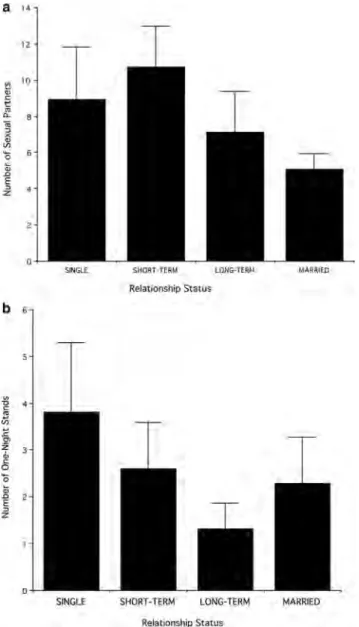

Figure 4a illustrates the lifetime number of

sexual partners for Caucasian, African, and His-panic men who were single and in short-term relationships, long-term relationships, or mar-ried. Although men who were single and in short-term relationships had a higher average number of sexual partners than men in long-term relationships or married, the overall differ-ence among the four groups was not statistically significant, F(3, 63) ⫽ 1.85; NS. Figure 4b

shows the lifetime number of one-night stands for Caucasian, African, and Hispanic men who were single and men who were in short-term

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

relationships, long-term relationships, or mar-ried. Again, single men and men in short-term relationships had, on average, more one-night stands than men who were in long-term rela-tionships or married but the overall difference

among the groups was not statistically signifi-cant,F(3, 63)⫽1.46; NS. When, however, data from the long-term relationship and married groups were pooled together, both scored sig-nificantly lower than single men and men in

Figure 2. (a). Mean (⫹ SE) number of lifetime sexual partners for Asian men (one homosexual Indian man who had 40 different sexual partners was a population outlier and excluded from data analyses) who were single and in relationships and for men who were single and in relationships in the other ethnic groups (Caucasian, African, and Hispanic) combined. (b) Mean (⫹SE) number of lifetime one-night-stands for Asian men who were single and in relationships and for men who were single and in relationships in the other ethnic groups (Caucasian, African, and Hispanic) combined.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

short-term relationships on both the lifetime number of sexual partners (long-term⫽5.51⫹ 0.81; others⫽9.81⫹1.81;t⫽2.21;df⫽62; p⬍.05) and the lifetime number of one-night stands (long-term ⫽ 1.51 ⫹ 0.49; others ⫽ 3.22⫹ 0.82;t⫽ 2.01;df⫽62; p⬍ .05).

Data for Asian men were insufficient for sta-tistical comparisons of testosterone levels, num-ber of lifetime sexual partners, and numnum-ber of one-night stands across different relationship categories. Moreover, there were no married Asian men in the subject population. Neverthe-less, for the purposes of qualitative compari-sons, means and standard errors for the three variables for Asian men who were single, in short-term relationships and in long-term rela-tionships are presented in Table 1. Similar to what was shown for the men in the other three ethnic groups (but with some differences in the absolute values), Asian men in short-term rela-tionships scored higher than those in long-term relationships in all three variables. Unlike the other ethnic groups, however, Asian single men scored relatively low in all three variables, and especially in testosterone levels.

Discussion

The results of our study shed new light on the association between relationship status, sexual promiscuity, and testosterone levels in men.

Specifically, they showed that single men have higher testosterone levels than men in relation-ships only in so far as single men are more sexually promiscuous than men in relationships. If single men show low levels of sexual promis-cuity, the difference in testosterone can be re-versed, with single men having lower testoster-one than men in relationships. Therefore, testosterone levels are not affected by relation-ship status in itself (e.g., through some psycho-logical condition associated with being single or having a partner) but by differences in sexual promiscuity that are generally correlated with differences in relationship status. Therefore, a man’s testosterone specifically tracks his mat-ing effort rather than his social life or psycho-logical state.

In our study, we used ethnicity as a tool with which to investigate potential variation in tes-tosterone within and across relationship status categories. First, using a larger, historical data-base consisting of male MBA students, we con-firmed the previously reported finding (see be-ginning of article for references) that among Western college students of predominantly Eu-ropean American (i.e., Caucasian) ethnicity, single men have, on average, higher testoster-one levels than men in relationships. Then, we showed that this testosterone difference was driven by Caucasian, Hispanic, and African men. Among men of Indian origin, single men

Figure 3. Mean (⫹SE) testosterone levels in single men, men in short-term relationships, men in long-term relationships, and married men. Data combined for Caucasian, Hispanic, and African men.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

and men in relationships had similar testoster-one levels, although among men of East Asian origin (e.g., Japan, China, and Taiwan) the dif-ference was significant but reversed: single men had lower testosterone than men in relation-ships. The same pattern was replicated in an-other ethnically diverse, but smaller sample of

mainly students at the same academic institu-tion. Here again, Asian men (which included mostly East Asians) who were single had sig-nificantly lower testosterone than men in rela-tionships. Asian single men had the lowest tes-tosterone levels among single men of all ethnic groups, and ethnic variation in testosterone

lev-Figure 4. (a). Mean (⫹SE) number of lifetime sexual partners among single men, men in short-term relationships, men in long-term relationships, and married men. Data combined for Caucasian, Hispanic, and African men. (b). Mean (⫹SE) number of lifetime one-night-stands among single men, men in short-term relationships, men in long-term relationships and married men. Data combined for Caucasian, Hispanic, and African men.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

els among men in relationships was not statis-tically significant.

In our study, Asian American men, regardless of their relationship status, reported a lower number of lifetime sexual partners and a lower number of lifetime one-night stands than Euro-pean American, African American, and His-panic American men. The Asian American men in our study also reported that they had never had extrapair sex in their lifetime and a slightly lower frequency of extrapair sex fantasies when compared with the other men. These results are consistent with those of previous studies show-ing that male Asian American college students are more sexually conservative and less sexu-ally experienced than men of other ethnic groups (Meston et al., 1996;Okazaki, 2002). In these previous studies, differences in sexuality between Asian American and non-Asian Amer-ican students were attributed to cultural norms. For example,Meston et al. (1996)reported that the more acculturated Asian-Canadians were to Canadian culture the less conservative their sex-ual attitudes. Although it should not be assumed that there are no differences in sexual norms among college students of European American, African American, and Hispanic American eth-nicity, previous studies that have specifically compared these three ethnic groups with Asian Americans have reported that differences in sexual conservatism among European Ameri-can, African AmeriAmeri-can, and Hispanic American youths are relatively minor when compared with those between these three groups and Asian Americans (e.g., East, 1998; Feldman, Turner, & Araujo, 1999).

In our study none of our four measures of sexual promiscuity was significantly correlated with testosterone levels across men of all eth-nicities but it is worth noting that Asian Amer-ican single men had the lowest scores on the number of lifetime sexual partners and the num-ber of one-night stands (data on extrapair sex

events and extrapair sex fantasies were analyzed only for men in relationships) and the lowest testosterone levels of all men in our subject population, including Asian American men in relationships. It is very likely that the testoster-one levels of single Asian American men are linked to their sexuality in a meaningful way although our data do not demonstrate clear di-rectional causality between testosterone and sexual promiscuity. The small sample size for analyzing relationships between ethnicity, sex-ual promiscuity and testosterone is one of the limitations of this study. It is possible that a stronger association between these variables would have emerged if a larger dataset had been available (e.g., see Bogaert & Fisher, 1995). Until some of our findings are replicated with a larger dataset, they should be interpreted with caution. The association between ethnicity, re-lationship status, and testosterone, however, ap-peared to be robust and was replicated in two different datasets.

It is highly unlikely that our reported ethnic differences in the relationship between male testosterone levels and relationship status reflect any ethnicity-related genetic differences in tes-tosterone or in sexuality (e.g.,Rohrmann et al., 2007; but seeEllis & Nyborg, 1992). Our ten-tative explanation of our findings, instead, has to do with the heterogeneity of the “singles” category. As already mentioned in the begin-ning of this article, in subject populations that mainly consist of college students, it is likely that among single males there are both highly sexually active individuals and individuals with low levels of sexual activity. It is possible that among male college students of Caucasian, His-panic, and African ethnicity, highly sexually active individuals represent the majority of sin-gle individuals and less sexually active sinsin-gles are relatively rare. The high testosterone levels of many sexually active singles may be respon-sible for the higher testosterone levels of singles Table 1

Testosterone and Sexual Experience in Asian Men in Relation to Relationship Status

Single (n) Short-Term (n) Long-Term (n) Testosterone 66.32⫹10.88 (5) 139.28⫹78.50 (2) 86.78⫹21.41 (3) Number of sexual partners 1.33⫹0.33 (6) 4.00⫹3.00 (2) 0.33⫹0.33 (3) Number of one-night stands 0.33⫹0.21 (6) 0.50⫹0.50 (2) 0 (3)

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

compared with men in relationships. Con-versely, it is possible that less sexually active individuals may have been the majority of Asian single men in our study. If less sexually active individuals have relatively low testoster-one, this may explain why single Asian men had low testosterone and particularly lower testos-terone than Asian men in relationships. Why there may be lower sexual activity among Asian single men than among other single men re-mains unclear: it may be the result of choice or constraints, both of which may be due to cul-tural or experiential factors.

Consistent with the above explanation, in the Caucasian, Hispanic, and African ethnic groups, single men scored higher, on average, than men in relationships on measures of lifetime sexual partners and lifetime number of one-night-stands. In these ethnic groups, married men and unmarried men in long-term relationships scored lower on these sexuality measures than single men and men in short-term relationships. Variation in testosterone levels appeared to track relationship length, as men in short-term relationships had the second-highest levels of testosterone after single men, followed by men in long-term relationships, who in turn had higher testosterone than married men. Simi-larly, among Asian men in relationships, un-married men in long-term relationships scored lower than men in short-term relationships in measures of testosterone, number of lifetime sexual partners, and lifetime number of one-night stands. Again, the small sample sizes for the analyses of testosterone levels and relation-ship status in different ethnic groups are among the metholodogical limitations of this study. Our findings, however, are consistent with those of previous studies showing a negative effect of relationship length and marriage on male testos-terone levels (see beginning of the article for references). The lack of married men among Asian men in relationships may have contrib-uted to the relatively high average testosterone observed in this group of study participants and to the magnitude of the difference in testoster-one between single men and men in relationship in the 2013 dataset.

Although the Asian and non-Asian ethnic groups showed an opposite difference in testos-terone between single men and men in relation-ships, several lines of evidence suggest that variation in male testosterone levels across all

ethnic groups tracks variation in sexual activity and sexual experience. It is likely that both psychological and physiological aspects of sex-ual activity (e.g., both thinking about sex and ejaculating) are directly involved in regulation of testosterone production. Other psychological aspects of relationship status that are not strictly related to sexuality, such as romantic commit-ment to a partner, stress, or social support, are unlikely to account for the association between relationship status and testosterone. Similarly, the possible cultural and experiential factors that affect ethnic variation in sexual conserva-tism or sexual activity are likely to be linked to variation in testosterone through their effects on sexual activity, rather than directly or through other variables. Other relatively stable charac-teristics such as personality could also affect variation in testosterone through their effects on sexual activity.

As for the specific aspects of sexual behavior that are most directly linked to testosterone, our measures of lifetime sexual experience (number of partners and number of one-night-stands) as well as of extrapair sex were measures of sexual promiscuity rather than of overall frequency of sexual activity. Thus, our data indicated that among Caucasian, Hispanic, and African men, single men, and to a lesser extent also men in short-term relationships, were more sexually promiscuous but did not necessarily engage in more frequent sexual activity than men in long-term relationships or married men. Differences in testosterone matched these differences in sex-ual promiscuity.

Previous studies have shown that a man’s testosterone increases following exposure to a potential sexual partner and that this increase is proportional to the intensity of his courtship effort (Roney et al., 2003;2007;van der Meij,

Buunk, van de Sande, & Salvador, 2008). In

contrast, engaging in sexual interactions with the same partner in the context of a stable mo-nogamous relationship does not seem to affect testosterone. Differences in testosterone be-tween individuals or changes in a man’s testos-terone levels over time provide a reliable indi-cator of variation in mating effort, which in men mainly consists of an effort to mate with an increasing number of partners. Measuring tes-tosterone, therefore, is an indispensable tool for understanding variation in male mating

strate-This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

gies as well as the life history trade-offs be-tween mating and survival or parenting efforts.

References

Berg, S. J., & Wynne-Edwards, K. E. (2001). Changes in testosterone, cortisol, and estradiol lev-els in men becoming fathers. Mayo Clinic

Pro-ceedings, 76,582–592.

Bogaert, A. F., & Fisher, W. A. (1995). Predictors of university men’s number of sexual partners.

Jour-nal of Sex Research, 32, 119 –130. doi:10.1080/

00224499509551782

Booth, A., & Dabbs, J. M., Jr. (1993). Testosterone and men’s marriages.Social Forces, 72,463– 477. Bribiescas, R. G. (2006). Men: Evolutionary and life-history. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Burnham, T. C., Chapman, J. F., Gray, P. B., McIn-tyre, M. H., Lipson, S. F., & Ellison, P. T. (2003). Men in committed, romantic relationships have lower testosterone.Hormones and Behavior, 44, 119 –122.doi:10.1016/S0018-506X(03)00125-9 East, P. L. (1998). Racial and ethnic differences in

girls’ sexual, marital, and birth expectations.

Jour-nal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 150 –162.

doi:10.2307/353448

Ellis, L., & Nyborg, H. (1992). Racial/ethnic varia-tions in male testosterone levels: A probable con-tributor to group differences in health.Steroids, 57, 72–75.doi:10.1016/0039-128X(92)90032-5 Feldman, S. S., Turner, R. A., & Araujo, K. (1999).

Interpersonal context as an influence on sexual timetables of youths: Gender and ethnic effects.

Journal of Research on Adolescence, 9, 25–52.

doi:10.1207/s15327795jra0901_2

Fleming, A. S., Corter, C., Stallings, J., & Steiner, M. (2002). Testosterone and prolactin are associated with emotional responses to infant cries in new fathers. Hormones and Behavior, 42, 399 – 413. doi:10.1006/hbeh.2002.1840

Gettler, L. T., McDade, T. W., Agustin, S. S., Feranil, A. B., & Kuzawa, C. W. (2013). Do testosterone declines during the transition to marriage and fa-therhood relate to men’s sexual behavior? Evi-dence from the Philippines.Hormones and

Behav-ior, 64, 755–763. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.08

.019

Gettler, L. T., McDade, T. W., Feranil, A. B., & Kuzawa, C. W. (2011). Longitudinal evidence that fatherhood decreases testosterone in human males. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,

USA, 108, 16194 –16199. doi:10.1073/pnas

.1105403108

Gettler, L. T., McKenna, J. J., McDade, T. W., Agus-tin, S. S., & Kuzawa, C. W. (2012). Does cosleep-ing contribute to lower testosterone levels in

fa-thers? Evidence from the Philippines.PLOS ONE, 7,e41559.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041559 Gray, P. B. (2003). Marriage, parenting, and

testos-terone variation among Kenyan Swahili men. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 122, 279 –286.doi:10.1002/ajpa.10293

Gray, P. B., & Campbell, B. C. (2009). Human male testosterone, pair-bonding, and fatherhood. In P. T. Ellison & P. B. Gray (Eds.), Endocrinology of

social relationships (pp. 270 –293). Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

Gray, P. B., Chapman, J. F., Burnham, T. C., McIn-tyre, M. H., Lipson, S. F., & Ellison, P. T. (2004). Human male pair bonding and testosterone.

Hu-man Nature, 15, 119 –131.

doi:10.1007/s12110-004-1016-6

Hirschenhauser, K., Frigerio, D., Grammer, K., & Magnusson, M. S. (2002). Monthly patterns of testosterone and behavior in prospective fathers.

Hormones and Behavior, 42, 172–181. doi:

10.1006/hbeh.2002.1815

Jasienska, G., Jasienski, M., & Ellison, P. T. (2012). Testosterone levels correlate with the number of children in human males, but the direction of the relationship depends on paternal education.

Evolu-tion and Human Behavior, 33, 665– 671. doi:

10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2012.05.001

Kuzawa, C. W., Gettler, L. T., Muller, M. N., Mc-Dade, T. W., & Feranil, A. B. (2009). Fatherhood, pair-bonding and testosterone in the Philippines.

Hormones and Behavior, 56, 429 – 435. doi:

10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.07.010

Maestripieri, D., Baran, N. M., Sapienza, P., & Zin-gales, L. (2010). Between- and within-sex varia-tion in hormonal responses to psychological stress in a large sample of college students. Stress, 13, 413– 424.doi:10.3109/10253891003681137 McIntyre, M., Gangestad, S. W., Gray, P. B.,

Chap-man, J. F., Burnham, T. C., O’Rourke, M. T., & Thornhill, R. (2006). Romantic involvement often reduces men’s testosterone levels-but not always: The moderating role of extrapair sexual interest. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 642– 651.doi:10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.642 Meston, C. M., Trapnell, P. D., & Gorzalka, B. B.

(1996). Ethnic and gender differences in sexuality: Variations in sexual behavior between Asian and non-Asian university students.Archives of Sexual

Behavior, 25,33–72.doi:10.1007/BF02437906

Muller, M. N., Marlowe, F. W., Bugumba, R., & Ellison, P. T. (2009). Testosterone and paternal care in East African foragers and pastoralists. Pro-ceedings of the Royal Society of London B, 276, 347–354.doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1028

Nelson, R. J. (2011).An introduction to behavioral endocrinology, 4th ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Okazaki, S. (2002). Influences of culture on Asian Americans’ sexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 39,34 – 41.doi:10.1080/00224490209552117 Perini, T., Ditzen, B., Fischbacher, S., & Ehlert, U.

(2012). Testosterone and relationship quality across the transition to fatherhood.Biological

Psy-chology, 90, 186 –191. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho

.2012.03.004

Rohrmann, S., Nelson, W. G., Rifai, N., Brown, T. R., Dobs, A., Kanarek, N., . . . Platz, E. A. (2007). Serum estrogen, but not testosterone levels differ between black and white men in a nationally representative sample of Americans. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 92, 2519 –2525.doi:10.1210/jc.2007-0028

Roney, J. R., Lukaszewski, A. W., & Simmons, Z. L. (2007). Rapid endocrine responses of young men to social interactions with young women.

Hor-mones and Behavior, 52,326 –333. doi:10.1016/j

.yhbeh.2007.05.008

Roney, J. R., Mahler, S. V., & Maestripieri, D. (2003). Behavioral and hormonal responses of men to brief interactions with women.Evolution

and Human Behavior, 24,365–375.doi:10.1016/

S1090-5138(03)00053-9

Sapienza, P., Zingales, L., & Maestripieri, D. (2009). Gender differences in financial risk aversion and career choices are affected by testosterone. Pro-ceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,

USA, 106, 15268 –15273. doi:10.1073/pnas

.0907352106

Storey, A. E., Walsh, C. J., Quinton, R. L., & Wynne-Edwards, K. E. (2000). Hormonal correlates of paternal responsiveness in new and expectant fa-thers.Evolution and Human Behavior, 21,79 –95. doi:10.1016/S1090-5138(99)00042-2

van Anders, S. M., & Goldey, K. L. (2010). Testos-terone and partnering are linked via relationship status for women and “relationship orientation” for

men.Hormones and Behavior, 58,820 – 826.doi:

10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.08.005

van Anders, S. M., Hamilton, L. D., & Watson, N. V. (2007). Multiple partners are associated with higher testosterone in North American men and women. Hormones and Behavior, 51, 454 – 459. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.01.002

van Anders, S. M., Tolman, R. M., & Volling, B. L. (2012). Baby cries and nurturance affect testoster-one in men.Hormones and Behavior, 61,31–36. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.09.012

van Anders, S. M., & Watson, N. V. (2006). Rela-tionship status and testosterone in North American heterosexual and non-heterosexual men and wom-en: Cross-sectional and longitudinal data.

Psycho-neuroendocrinology, 31, 715–723. doi:10.1016/j

.psyneuen.2006.01.008

van der Meij, L., Buunk, A. P., van de Sande, J. P., & Salvador, A. (2008). The presence of a woman increases testosterone in aggressive dominant men.

Hormones and Behavior, 54, 640 – 644. doi:

10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.07.001

Wingfield, J. C., Hegner, R. E., Dufty, A. M., & Ball, G. F. (1990). The “challenge hypothesis:” Theo-retical implications for patterns of testosterone se-cretion, mating systems, and breeding strategies.

American Naturalist, 136,829 – 846.doi:10.1086/

285134

Received October 30, 2013 Revision received December 18, 2013

Accepted January 9, 2014 䡲 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.