MAIN CONCLUSIONS

Of all the EU member states, Bulgaria is the country whose citizens are the least satisfied with the performance of the main government institutions.

Trust in the main institutions concerned with criminal justice in Bulgaria – the police and courts, is low and has remained practically unchanged over the last decade. At the end of 2010, a positive evaluation of police performance was given by less than half of the country’s adult population and barely one in five gave a favorable opinion of the courts.

The low public trust in the courts and police can also be accounted for by the high level of corruption in these institutions.

The low trust in the courts and police is conducive to public attitudes of insecurity. Society begins to perceive crime as an inherent part of reality rather than a problem that can actually be addressed.

A state’s penal policy can only produce results if sufficient attention is paid to trust, legitimacy, and security. It is therefore recommended to adopt a system of indicators for the assessment of public trust in criminal justice in Bulgaria.

These indicators are an instrument for improved formulation of the problems faced by criminal justice institutions and for more effective monitoring of changes in public attitudes. This would make it possible to focus the attention on strategic issues and long-term policies in the area of security and justice not only on the national, but also on the European level. In order to ensure comparability of the impact assessment of various implemented policies, it is recommended to adopt uniform indicators for measuring trust in criminal justice in the European Union and the member states, which should take place within the timeframe of the Stockholm Programme (2010-2014).

PUBLIC TRUST IN THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM –

AN INSTRUMENT FOR PENAL POLICY ASSESSMENT

Policy Brief No. 29, May 2011

Forging public policies based on trust between citizens and institutions is a key precondition for achieving sustainable development in a society founded on the principles of good governance and social justice and solidarity.1

In Bulgaria, public trust is still wrongly underestimated as a criterion in the development and implementation of sustainable and long-term public policies. This trust reflects citizens’ overall evaluation of the performance of government institutions: of their effectiveness, of the need for reforms and for impact assessment of measures already taken. This is particularly relevant in the area of criminal justice and crime prevention. The police and courts need public support and institutional legitimacy in order to function efficiently and in conformity with social and moral norms. In the Judicial Anti-Corruption Program developed by the Center for the Study of Democracy in 2003, public trust in the institutions is noted as a

1

Public trust in institutions, as well as interpersonal trust among citizens are directly related to the quality of life, which is conditioned by: i) objective living conditions, ii) subjective perception of well-being, and iii) degree of solidarity, social cohesion and stability in society. Trust is affected by several essential factors:

level of economic development (GDP growth) and of modernization (urbanization, life expectancy, industrial development, education levels of the general population, etc);

democracy (political rights and civil freedoms) and good governance (government and public spending, law and order, corruption index);

key precondition for a successful judicial reform. Despite the numerous international and national initiatives for the monitoring and assessment of these reforms, policy-making in the area of criminal justice still does not make use of indicators measuring trust in institutions. There equally lack strategies aimed at building and maintaining high levels of trust in the institutions of criminal justice. Instead, and in the pursuit of short-term political goals, various aspects of the pre-trial phase of criminal proceedings are overexposed – mainly through public arrests in cases of heightened public interest. Such police operations are presented as positive results of crime prevention although all too often, those apprehended may subsequently not even be charged.

System of indicators to measure

trust in criminal justice

Bulgaria and other EU member states face the need to adopt, following the example of USA and Great Britain, indicators of confidence in justice as an innovative tool in the elaboration and implementation of public policies in this area.

In response to this challenge, in 2010-2011, experts in the fields of law, sociology and criminology from several research centers in Europe (among them the Center for the Study of Democracy) developed and proposed to the institutions of the European Union and the member states a system of indicators for assessing confidence in the institutions of criminal

justice.2 The indicators are based on the assumption

2

Scientific Indicators of Confidence in Justice: Tools for Policy Assessment (EUROJUSTIS) Project, supported by the Seventh Framework Programme of the European Commission (http://www.eurojustis.eu). The adoption of these indicators in five European countries (Bulgaria, France, Italy, Lithuania, and the Czech Republic) marks the beginning of comparative European studies of the connection between trust and law abidance, following the model of USA, Great Britain, and other countries. In the fall of 2011, the elaborated indicators will be used in the fifth wave of the European Social Survey covering 28 countries. Its findings traditionally attract much interest on the part of

that an assessment of the effectiveness of the justice system should not only take into account narrow criteria of crime control, but also broader criteria relating to people’s trust in this system. Trust is viewed as a composite indicator reflecting two interrelated aspects of public opinion. The first one records public trust in the police and courts in terms of i) efficiency, ii) compliance with rules and procedures, i.e. procedural fairness, and iii) impartial treatment irrespective of citizens’ social, economic, or political status. The second aspect covers opinions about the legitimacy of these institutions, i.e. people’s perceptions regarding the enforcement and observation of the fundamental principles of democracy, rule of law, and equal footing in the activity of the institutions. As a result, when used as a toll for political innovation, the system of indicators makes it possible to assess both the subjective perception of legitimacy and its normative aspect. The latter is measured through national-level indicators of accountability, transparency, principles of democratic governance, corruption levels, etc. In this sense, the developed system of indicators also provides the possibility to monitor the “overtaking of criminal justice by the Executive”, i.e. of any unlawful or undue pressure and control over the police and courts by central and local government and by politically protected big business.

The creation of a system of indicators of confidence in criminal justice and its adoption as a policy-making tool fully meets one of the fundamental priorities of the Stockholm Programme for EU development in the area of security and justice in

the period 2010-2014.3 An essential instrument and

at the same time a challenge for the achievement of its goals is fostering trust between citizens and law-enforcement institutions both on the national and the European level. Terrorism, cyber crime, border control and migration are only some of the more

researchers and politicians since they provide up-to-date and reliable information about European public opinion on important social issues.

3

The Stockholm Programme - an Open and Secure Europe Serving and Protecting Citizens (2010/C 115/01).

notable areas for which the Stockholm Programme urges for the adoption of trust-based policies.

Bulgaria – a low-trust society

Comparative European surveys conducted in the past five years have shown that of all EU member states, Bulgaria is the country whose citizens are the least satisfied with the performance of the main

government institutions.4 Modern Bulgarian society is

a low-trust society both in terms of interpersonal trust and confidence in the institutions. In the EU Bulgarian citizens report the lowest levels of trust in the representatives of the political class and the institutions. In this respect, politicians rank ‘first’, followed by political parties, parliament, the judicial system, and the police. These low levels of trust have been a lasting attitude on the part of growing number of Bulgarians since 2003. This equally applies to popular attitudes regarding the performance of the authorities in charge of crime prevention and supposed to guarantee citizens’ security and the rule of law in society.

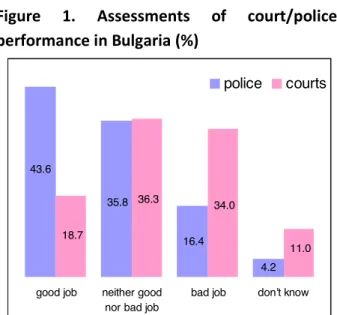

At the end of 2010, fewer than half of the Bulgarian citizens made a favorable evaluation of the

performance of the courts and the police.5 Of those,

the citizens who assessed favorably the work of the police (43.6%) outnumber more than twice those who did so for the courts (18.7%). Opinions about the police are almost the same across all age groups while regarding the courts the proportion of citizens who assessed them favorably tends to decline the higher their age.6

4

European Social Survey 2006 and 2009; European Quality of Life Survey 2003 and 2007; European Value Survey 2008.

5

National representative survey of the adult population of Bulgaria, October 2010 (EUROJUSTIS Pilot Survey, October 2010).

6

The highest age group (those aged 80 and over) was the only one where approval of court performance was higher than in the preceding age group (70-80 years of age).

Figure 1. Assessments of court/police performance in Bulgaria (%) 43.6 35.8 16.4 4.2 18.7 36.3 34.0 11.0

good job neither good nor bad job

bad job don’t know police courts

Source: EUROJUSTIS Pilot Survey, October 2010

The negative popular assessment of the work of the police and the courts matches the low trust in government institutions as a whole observed over the past decade. It also affects citizens’ sense of security and safety, deepening their concern that they might fall victim to crime. The relative proportion of Bulgarian citizens who shared their

concern about the most common crimes7 – burglary

and physical assault in the street exceeds three and seven times, respectively, the share of those who in the past five years have actually been victims of such crimes or who personally know some other victim. Some of the main reasons for the popular perception that crime is on the rise despite its objective decline, both in the number of registered and unreported crimes, are the overexposure of the topic in the media and the fact that crime prevention measures have become a basic political and pre-election tool. This also finds confirmation in the National Crime Surveys conducted since 2000 by the Center for the Study of Democracy.

7

Conventional Crime in Bulgaria: Levels and Trends. Center for the Study of Democracy, 2009.

Figure 2. Fear of crime and crime victims (%) 32.8 35.3 14.3 23.3 88.6 66.6 64.7 96.8 85.0 76.1 11.3 3.1

has been the vic tim of a burglary in the last 5 years know s someone in the same area w ho has been the v ic tim of

a burglary in the las t 5 y ears during the last 12 months have f elt w orried about having their home broken into and something

stolen has been the v ic tim of a phy sical assault in the street by

a stranger in the last 5 years know s someone in the same area w ho has been the v ic tim of

a physical assault in the s treet by a stranger in the las t 5 y ears during the last 12 months has

f elt w orried about being physically attacked in the street

by a s tranger

yes no

Source: EUROJUSTIS Pilot Survey, October 2010

The inadequate efficiency of law enforcement authorities and the need to improve the treatment of the victims are among the most commonly cited reasons why victims are reluctant to report the crime

they have suffered to the police.8 The results of

several consecutive National Crime Surveys indicate that the increased public confidence in criminal justice is of key importance for reducing the latency level in crime reporting. Greater public trust in the work of the police, prosecution, and the courts is a precondition for reinforcing the authority of these institutions and motivates citizens to offer assistance in crime exposure and investigation. Conversely, low public trust in criminal justice gives rise to a perception of impunity and thwarts people’s readiness to cooperate, which in turn affects

8

In the period 2001-2008, the share of crimes reported to the police out of all crimes committed remained almost unchanged – on average 51.3% per year. Conventional Crime in Bulgaria: Levels and Trends. Center for the Study of Democracy, 2009.

adversely the efficiency of law-enforcement authorities.

People’s subjective fear they might fall victim to crime significantly exceeds (three to seven times in terms of a 5-year period, and fifteen times when considering a period longer than 5 years) the actual

occurrence of such incidents.9 This subjective

concern affects both personal attitudes and the perceived attitudes of others. Society is beginning to regard crime as part of the reality in this country, rather than as a problem that can actually be addressed. The majority of citizens (80%) believe crime is part of life in Bulgaria and about as many think most people in this country are taking precautions and fear they might fall victim to crime. The discrepancy between the fact that more than half of the Bulgarian citizens think they might become victims of crime while a much smaller share (20%) believe this affects their quality of life may be interpreted in terms of the perception of criminal behavior as part of the way of life.

Figure 3. Are you concerned you might fall victim to: (%) 33.6 50.0 46.3 56.3 54.5 54.4 65.8 49.1 52.5 42.2 42.5 43.0

ins ult or pes t er by any body while in t he s t reet m ugging/ robbery in t he s t reet a phy s ic al at t ac k by s t rangers in t he s t reet burglery c ar t hef t * hav ing t hings s t olen f rom y our

c ar*

worried not worried

* in % of car owners

Source: EUROJUSTIS Pilot Survey, October 2010

9

The high level of concern about crime and the low trust in the work of the police also stem from citizens’ poor assessment of police efficiency in the execution of its specific tasks and duties. Very few Bulgarians believe the police are effective in preventing grave crimes (17.7%), apprehending burglars (13.2%) or with regard to speedy response to crime reports (24.6%).

Public opinion about criminal court performance is even more negative. The share of those who believe courts are coping well is considerably smaller and respectively, those who make entirely negative assessments are about twice as many as with regard to the police. This attitude concerns both court efficiency and court fairness in terms of observation of procedural rules and the impartial treatment of the accused.

According to more than half of the citizens (56.0%), the courts make mistakes allowing for the acquittal of guilty persons. About one-third of the citizens (34.5%) are of the opinion that the courts violate, though with varying frequency, the formal procedural rules. Even fewer people believe the courts demonstrate an impartial attitude to the defendants regardless of their economic, political or social status. In line with these opinions, the majority of the citizens (72.7%) think the courts are subordinate to economic interests and according to more than half (56.9%), the courts are also susceptible to political influence when deciding the outcome of the cases.

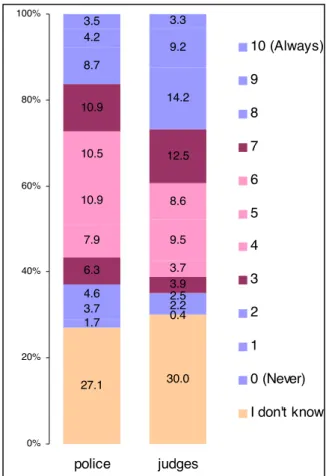

The low public confidence in the courts and the police is also related to the citizens’ opinion about the level of corruption in these institutions. Barely about one-tenth of the citizens (9.9%) think police officers do not accept bribes while merely one-twentieth (5.1%)

share the same opinion about court officials.10

10

The findings of the Corruption Monitoring System show a steady tendency in public opinion regarding the increasing level of corruption in the judicial system and the police in the period 2000-2007 (between 55% and 70% of the population). The occupations of police officer, judge, prosecutor, and investigator are enduringly associated with corrupt practices by half of the country’s adult population. Customs officers represent the only other occupation

Figure 4. How often do police officers / judges accept bribes (%) 27.1 30.0 1.7 4.6 6.3 3.9 7.9 3.7 10.9 9.5 10.5 8.6 10.9 12.5 8.7 14.2 4.2 9.2 3.5 3.3 0.4 3.7 2.2 2.5 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% police judges 10 (Always) 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 (Never) I don't know

Source: EUROJUSTIS Pilot Survey, October 2010

Public trust and reforming

penal policy

The legislative and institutional reforms in criminal justice have not brought about the anticipated

surpassing these assessments by about 10 percentage points (Anti-Corruption Reforms in Bulgaria: Key Results and Risks, Center for the Study of Democracy, 2007, pp. 16-17). A public opinion poll in EU27 indicates that, in the period 2007-2009, the share of Bulgarian citizens who believe there is corruption among those working in the judicial system increased from 64% to 82%, which ranks this country first in the EU (37% on average for EU27) in absolute terms and in the third place by rate of increase (Attitudes of Europeans towards Corruption, Special Eurobarometer, November 2009).

decline in corruption and improved efficiency of the system as a whole.

1) Due to the lack of a long-term and consistent

concept for the development the state’s penal policy, with clearly defined goals and priorities, most of the implemented changes were fragmentary and failed to help improve efficiency in the work of the police and the courts.

2) All too often the reforms undertaken proved so

ineffective that they had to be revised very soon after their adoption.

3) A number of institutional and legislative changes

were made for the sole purpose of formally meeting the requirements of the European Union without taking into consideration their long-term implications.

As a result, the police increasingly came to rely on widely publicized operations rather than a reform of the system while the courts have come to feel independent even from the very society they are supposed to serve.

The state has failed to respond adequately to widespread popular concerns about political corruption, conflict of interests, and misuse of public funds for personal gain. Most of the pre-trial corruption proceedings for corruption never even reach court due to the ineffectively conducted investigation by the authorities of pre-trial criminal

proceedings.11 In this respect, the Prosecutor’s Office

is particularly accountable since it both supervises the pre-trial stage of the proceedings and is involved in the supervision of the judiciary through its representatives in the Supreme Judicial Council. Thus, a large part of corruption and organized crime remains practically unpunished since, in addition to the cases that never go to court, about one-third of

11

According to data of the Supreme Prosecutor’s Office of Cassation and the Ministry of Justice in the period 2004-2007, nearly 80% of the instigated pre-trial proceedings for corruption related crimes were closed at the pre-trial stage. Of those that were brought to court, in the period 2000-2007, 34.9% were suspended (Crime without Punishment: Countering Corruption and Organized Crime in Bulgaria. Center for the Study of Democracy, 2009, p. 11)

the instigated criminal trials for such crimes conclude without convictions. Added to this are the flaws in the legal framework regulating the crimes, punishments (Criminal Code), and the rules for their enforcement (Criminal Procedure Code). All this affects the public confidence in the institutions, reinforces the notion of “crime without punishment” and helps sustain the continually high levels of public mistrust in state institutions in general, and the police and the courts, in particular. Another reason for the low public trust in the courts is the lack of publicly visible results in counteracting the internal corruption in the Judiciary. The insignificant number of disciplinary and criminal proceedings against representatives of the Judiciary strongly contrasts with the widespread suspicions of trade in influence within the Supreme Judicial Council in relation with high-ranking appointments to the courts and the Prosecutor’s Office; of undue material gain on the part of magistrates and their families; of subjectiveness and partiality in conducting competitions within the judiciary, etc. The practice of the Ministry of the Interior, demonstrating police action for the apprehension of suspects and laying the responsibility for subsequent decisions typically on the courts alone, can only have a positive impact in the short term. In the long term, this undermines confidence in the efficiency of the Ministry of the Interior due to acquittals or failure to bring charges in court at all, including in cases of significant public interest. This practice leads to opposition between the individual institutions of criminal justice, which in turn affects adversely the performance of the entire system. This effect is further reinforced by the lack of an integrated strategy of criminal justice institutions for communication with the public, which should emphasize the shared responsibilities and the results produced by the system as a whole. For these reasons, the most important sources of information about the activities of the police and the courts in Bulgaria remain the personal experience and the shared experience of one’s friends and family. The media, as intermediaries

between government institutions and the public, only come third in this respect.

Figure 5. Sources of information about police/court activity (%) 81.2 67.5 76.2 68.7 70.2 67.7 54.5 52.4 49.4 50.8 33.1 32.6 29.6 28.6 8.5 10.6 12.8 14.5 18.2 19.6 20.7 22.4 22.2 21.4 17.2 16.9 17.6 18.1 11.8 10.3 11.7 9.8 18.0 17.1 18.7 17.6 34.2 35.7 4.4 10.1 4.2 6.3 4.5 4.5 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% police c ourts police c ourts police c ourts police c ourts police c ourts police c ourts police c ourts P e r s on al ex pe r ien c e Fr ie n d s , f a m ily me m b e r s , ne ig hb ou r s T e le vi si o n / ra d io News p a p e r s / m a g a z ine s E du c a t io n O n lin e n e w s pa pe r s / n e w s po r t a ls On li n e pr iv a t e pa ge s / bl o g s / fo r u m s

Important Neither important nor unimportant

Not important Don’t

Source: EUROJUSTIS Pilot Survey, October 2010

The low trust and sense of impunity are largely sustained by the absence of convictions in the cases of heightened public interest. The media coverage of these cases is an important factor in forging popular attitudes regarding the effectiveness of criminal justice. The resulting presumptions of guilt from the disclosed data about serious violations and the fact that the trials drag out for years, as well as the pronouncement of acquittals in some of these cases, logically contribute towards low public confidence in criminal justice.

In terms of public policy-making, the low public confidence in the police and the courts affects negatively the reforms undertaken. Overcoming this deficit calls for the development of an instrument for assessment of the policies in the area of criminal justice which should not only comprise statistical data about the judicial system and the police, but likewise regular monitoring of trust in these institutions both on the part of the general public and specifically the persons entering into contacts with them (defendants, victims, witnesses, etc). Such an instrument would also facilitate the adoption of good practices from countries with developed trust-based policies (Great Britain, USA, the Scandinavian countries, Italy and others). Along with the introduction of an assessment tool based on public trust, it is also necessary to undertake specific measures to enhance citizens’ confidence in criminal justice. These measures should aim to:

1) Improve the interaction between the

institutions of the criminal justice system and the public and raise public awareness by providing regular and accessible information about the results from the work of the judicial system and the police;

2) Build the capacity of the criminal justice

institutions for communication and interaction with the general public; expand and optimize as far as possible the adoption and use of new technologies for providing electronic access to information in order to reduce the corruption pressure by enhancing the transparency of the institutions and the awareness of the general public;

3) Improve the coordination and interaction

between the institutions of the criminal justice system in order to restrict mutual accusations of incompetence and inefficiency;

4) Enhance the internal control against

malpractice and violations on the part of members of the police and the judicial system and make publicly available the conclusions of the inquiries and any measures taken.