Received for publication Jul 25, 1990; accepted Dec 5, 1990. PEDIATRICS (ISSN 0031 4005). Copyright © 1991 by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Early

Formula

Supplementation

of

Breast-Feeding

Natalie

Kunnij,

PhD,*

and Patricia

H. Shiono,

PhDf

From the *Collaborative Clinical Research Branch, National Eye Institute, National

Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, and tCenter for the Future of Children, David

and Lucille Packard Foundation, Los Altos, California

ABSTRACT. Factors influencing early formula

supple-mentation in breast-fed neonates were examined among

726 women who were delivered of their first child in one

ofthree metropolitan Washington, DC, hospitals. Thirty-seven percent of breast-fed neonates were given supple-mentary formula in the hospital. Mothers who gave birth at a university hospital were more likely to breast-feed

exclusively (adjusted odds ratio 3.5; 95% confidence limit 2.1 to 5.9), after adjustment for maternal demographics, hospital factors (such as time of first breast-feed, demand feeding, delivery type, and rooming-in), and the maternal breast-feeding commitment. Aside from delivery hospital,

a strong predictor of formula use was the time between birth and initiation of the first breast-feed. The longer a mother waited to initiate breast-feeding the more likely

she was to use formula; the adjusted odds ratios for

women who initiated breast-feeding 2 to 6 hours, 7 to 11 hours, and 12 or more hours postpartum were 1.1, 0.5,

and 0.2, respectively. Feeding the baby on demand, hay-ing a vaginal delivery, deciding to breast-feed before

pregnancy, having a college education, and being married also were moderately, though significantly, predictive of

exclusive breast-feeding. The findings suggest that hos-pital influences can promote formula use and indirectly

shorten breast-feeding duration, particularly those

hos-pital practices that delay early initiation of

breast-feed-ing. Pediatrics 1991;88:745-750; breast-feeding, infant for-mula, supplementation.

Formula supplementation of breast-feeding has been consistently associated with a shortened

breast-feeding duration.’5 Although a causal

rela-tionship between formula use and discontinuation

of breast-feeding is difficult to establish, women who use formula supplements tend to breast-feed for a shorter time period than women who do not.’4 Moreover, women who introduce formula in

the early postpartum weeks have a higher rate of

breast-feeding discontinuation than women who

introduce formula in the later postpartum months.6 What remains unclear are the factors responsible for formula-supplemented breast-feeding, particu-larly formula use occurring in the early postpartum period. Formula supplementation may result from a maternal intention to stop breast-feeding, may be due to hospital influences (both staff and routines), or may reflect a lack of maternal confidence in

breast-feeding. The underlying cause of maternal

confidence in and commitment to breast-feeding are not easily understood; however, a hospital staff supportive of breast-feeding can bolster maternal confidence in the method.7 In contrast, hospital routines that restrict early initiation of breast-feed-ing by separating the mother from hen newborn after delivery can promote formula use. This sepa-ration thereby indirectly promotes a shortened du-ration of breast-feeding, if supplements replace breast milk.

We previously reported from a prospective survey of 755 breast-feeding women that 38% of neonates received formula supplements during the hospital

stay-a factor strongly predictive of a shortened

breast-feeding duration.’ In this paper we examine

maternal and hospital factors that might explain

why so many neonates of breast-feeding women are given supplementary formula. In particular, we

evaluate the influence of maternal

sociodemo-graphic characteristics, commitment to breast-feed, and the effect of specific hospital procedures on early formula use.

METHODS

were consecutively selected from the delivery logs at each of three metropolitan Washington, DC,

hospitals. Study procedures and the study design

have been described.1 To summarize, a total of 1409

women were asked to participate in the study and

84% (n = 1179) agreed. Women were interviewed

in the hospital between February 1984 and March

1985, after informed consent was obtained.

Sixty-four percent of the sample women initiated any

breast-feeding in the hospital.

Of the 755 women who breast-fed in the hospital,

29 women had not fed their newborn at the time of

the interview and were excluded from the present

analysis. Of the remaining 726 women, 456 (63%)

exclusively breast-fed. These 456 women defined

themselves as exclusively breast-feeding and

mdi-cated that the baby had not received formula

sup-plements in the hospital. Mixed feeders (n = 270)

were categorized based on their actual infant

feed-ing behavior in the hospital. Mixed feeders defined

themselves as simultaneously breast-feeding and

formula feeding (n = 100) on as exclusively

breast-feeding but indicated that the baby had received

formula in the hospital (n = 170). Categorization

of exclusive breast-feeders and mixed feeders was

based solely on maternal reports of the infant’s

being given supplementary formula. This formula

supplementation could have resulted from maternal choice on from hospital procedures. Definition of

feeding type did not take into consideration the

amount of formula offered to the neonate.

The following information was obtained during the hospital interview: maternal sociodernographic characteristics (age, education, marital status, net

family income, prenatal cane, and attendance in

childbirth classes); breast-feeding and

formula-feeding behavior; hospital procedures (delivery

type, timing of the first breast-feed, rooming-in,

and feeding pattern-demand, modified demand, or

schedule); and maternal commitment to breast-feed

(timing of decision to breast-feed and planned

du-nation of breast-feeding). The first maternal

re-sponse to an open-ended question regarding why

formula supplements were used was also examined. Eligible women were recruited consecutively for

4#{189}months at the public hospital, 13 months at the

community hospital, and 1 1 months at the

univer-sity hospital. Ninety percent of women were

inter-viewed during their hospital stay or in their baby’s

first 4 days of life. Because of an early discharge policy, 10% of women were not seen in the hospital

but were subsequently interviewed at home. No baby was older than 17 days at time of the first

interview.

The sociodemographic characteristics of

exclu-sive breast-feeders and mixed feeders were

evalu-ated by

x2

analysis.8 Logistic regression was usedto estimate the odds ratio for exclusive

breast-feeding vs mixed feeding while controlling for de-mographic factors, hospital procedures, and mater-nal commitment to breast-feed.9

RESULTS

Sixty-three percent of women (n = 726)

breast-fed without the use of formula supplements in the

hospital. Demographic predictors of exclusive

breast-feeding are presented in Table 1. The rate ofexclusive breast-feeding exceeded the overall rate

of 63% among women giving birth at the university hospital (86%), those with a college (65%) or

grad-uate school (75%) education, white women (74%),

married women (69%), those older than age 30

(71%), those receiving prenatal care from a private

physician (64%) on a health maintenance

organi-zation (85%), and those attending childbirth classes (65%). In the multivaniate model (Table 1) adjust-ing for education, ethnicity, marital status, age, type of prenatal care, and attendance in childbirth

classes, the strongest predictor of exclusive

breast-feeding vs mixed feeding was delivery at the

uni-vensity hospital (adjusted odds 3.5, 95% confidence

interval [CI] 2.1 to 6.0). The adjusted odds of

exclu-sive breast-feeding vs mixed feeding also were

sig-nificantly increased, approximately twofold, for

women having at least some college vs a high school

education, for white vs black women, and for those who were married (Table 1).

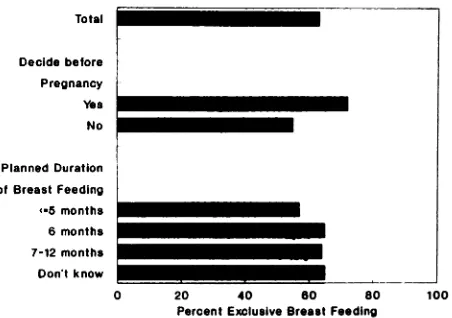

The associations between hospital factors, the

maternal commitment to breast-feed, and the

ex-clusive breast-feeding rate are presented in Figs 1 and 2. The rate of exclusive breast-feeding was higher than the overall proportion of 63% if the

women initiated breast-feeding in the first 6 hours

postpartum, if she delivered vaginally, or if she fed on demand (Fig 1). Rooming-in did not have an effect on exclusive breast-feeding (not shown). Women who decided to breast-feed before rather than during or after pregnancy were significantly

more likely to breast-feed exclusively, whereas

planned duration of breast-feeding

did

not affect the exclusive breast-feeding rate (Fig 2).We also evaluated the first maternal response to an open-ended question regarding why formula sup-plements were used (Table 2). The primary reasons given (n = 267) were “to give mother some nest”

(20%) or “mother ill” (18%). Other reasons given

were “not enough breast milk” (8%), “return to work” (6%), on “to make sure baby gets enough”

(6%). The most cited reason for use of formula at

Total

Hospital University Community Public

Delivery type Vaginal

Cesarean

First Breast Feed -2 hours 3-6 hours 7-12 hours 13. hours

Feeding Pattern

Demand

Modified demand

Schedule

0 20 40 60 80 100

Percent Exclusive Breast Feeding

Fig 1. Hospital factors and exclusive breast-feeding.

“to give mother some rest.” In contrast, the most

frequent reasons for use of formula supplements at

the community hospital was “mother ill” (40 of 177 respondents). The need for rest and recovery after delivery may be due to the type of delivery a women experienced because 71% ofthe 49 women who gave “mother ill” as a reason for formula use had been delivered of their neonate by cesarean section.

A logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine the effect of hospital procedures,

mater-0 20 40 60 80 100

Percent Exclusive Breast Feeding

Fig 2. Maternal commitment and exclusive breast-feed-ing.

nal commitment to breast-feed, and maternal

so-ciodemographic characteristics on exclusive

breast-feeding vs mixed feeding (Table 3). Delivery at the

university hospital remained a strong predictor of

exclusive vs mixed feeding (adjusted odds ratio 3.5,

95% CI 2.1 to 5.9) even after adjustment for all

other factors listed in Table 3 (the timing of the

first breast-feed, feeding pattern, delivery type,

rooming-in, timing of the decision to breast-feed,

TABLE 1. Demographic Predictors of Exclusive Breast-feeding

Factor No. %

Exclusive Breast-feeding*

Adjusted Odds Ratiof

95% Confidence

Interval

Hospital

Community 385 54 1.0 ...

Public 120 50 0.7 0.5-1.2

University 221 86 3.5 2.1-6.0

Education

12y 173 44 1.0 ...

13-16y 342 65 1.8 1.2-2.9

>16y 211 75 1.7 0.9-3.1

Ethnic group

Black 305 47 1.0 ...

White 421 74 2.2 1.4-3.2

Married

No 171 42 1.0 ...

Yes 554 69 1.7 1.1-2.6

Age

18-25 y 258 55 1.0 ...

26-30 y 246 63 0.7 0.5-1.1

>30y 222 71 0.7 0.4-1.2

Prenatal care

Private 535 64 1.0 ...

Clinic 120 47 0.9 0.6-1.5

HMO 65 85 1.2 0.5-2.8

Childbirth classes

No 148 53 1.0 ...

Yes 578 65 0.8 0.5-1.3

* x2statistics for each variable were statistically significant at P < .01.

t Because of missing data, adjusted odds ratios were calculated with data from 719 women. P<.05.

§Health maintenance organization.

Total

Decide before

Pregnancy

Yea No

Planned Duration of Breast Feeding (.5 months

TABLE 2. First Maternal Reason Given for Formula

Supplementation

Reason for Formula Use No. %

To give mother some rest 53 20

Mother ill 49 18

Not enough breast milk 22 8

Return to work 16 6

Make sure baby gets enough 15 6

To give mother more time 13 5

To fill baby up until milk comes 13 5 in

As a supplement 13 5

Baby rejects breast 13 5

Convenience 1 1 4

To increase blood sugar 1 1 4

Baby ill 10 4

Accustom baby to bottle 9 3

Hospital procedures 7 3

Freedom 5 2

Sore nipples 4 1

Let others feed baby 3 1

Total 267

education, marital status, and ethnicity). A first

breast-feed that occurred 7 to 12 hours postpartum on more than 12 hours postpartum decreased the odds of exclusive breast-feeding (adjusted odds 0.5, 95% CI 0.3 to 0.8 and adjusted odds 0.2, 95% CI 0.1 to 0.4, respectively). The odds of exclusive breast-feeding were increased approximately twofold for women delivering vaginally rather than by cesarean section, for those deciding to breast-feed before rather than during or after pregnancy, for those with some college vs a high school education, and for those who were married vs single. Women who breast-fed on a schedule rather than by demand decreased their odds of exclusive breast-feeding (adjusted odds 0.5, 95% CI 0.3 to 0.9). Ethnicity was not associated with exclusive breast-feeding.

DISCUSSION

Early formula supplementation in breast-fed

neonates is generally not recommended by medical

professionals.2 Yet, we found that 37% of breast-fed neonates (n = 726) were given supplementary

formula. This percentage varied by hospital of de-livery. Approximately half of the newborns of breast-feeding women delivered at the public or community hospital were given supplementary for-mula, whereas only 15% of newborns delivered at the university hospital were given formula.

Delivery at the university hospital was a strong

predictor of exclusive breast-feeding (adjusted odds

ratio 3.5, 95% CI 2.1 to 5.9) even after analyses

were controlled for maternal sociodemographic

characteristics, maternal commitment to

breast-TABLE 3. Hospital an clusive Breast-feeding

d Demogr aphi c Predictors of

Ex-Factor No.5 Odds

Ratio

95% Confidence Interval

Hospital

Community 333 1.0 ...

Public 114 1.0 0.6-1.7

University 208 3.5 2.1-5.9t

First breast-feed

2h 267 1.0 ...

2-6 h 137 1.1 0.7-1.9

7-12 h 133 0.5 O.3-0.8t

>12 h 118 0.2 0.1-0.4t

Feeding pattern

Demand 257 1.0 ...

Modified demand 223 0.8 0.5-1.3

Schedule 175 0.5 0.3-0.9t

Delivery

Vaginal 457 1.8 1.1-2.8t

Cesarean 198 1.0 ...

Rooming-in

Yes 436 1.4 0.9-2.2

No 219 1.0 ...

Decided to breast-feed

Before pregnancy 373 1.9 1.3-2.8t

During pregnancy 282 1.0 ...

Education

12y 156 1.0 ...

13-16y 305 1.6 1.0-2.6t

>16 y 194 1.3 0.7-2.3

Married

Yes 500 2.0 1.2-3.3t

No 154 1.0 ...

Ethnic group

White 388 1.1 0.7-1.7

Black 267 1.0 ...

* Total sample in this

analysis was 654 women after

exclusions for missing data and responses of “don’t know” to items regarding rooming-in, feeding pattern, and tim-ing of the first breast-feed.

t P < .05.

feed, and hospital procedures. The university hos-pital differed from the other two hospitals in the following ways: (1) a greater proportion of women initiated breast-feeding in the first 6 hours post-partum (74% vs approximately 50% at the other two hospitals); (2) a lower rate of cesarean

deliver-ies (25% compared with 34% at the community and

41% at the public county hospital); (3) a larger

proportion of married women (90% vs approxi-mately 70% at the other two hospitals); and (4) a larger proportion of white women (81% vs 63% at the public county and 43% at the community hos-pital). Even after analyses were controlled for these factors, women giving birth at the university hos-pital were more than 3#{189}times as likely to exclu-sively breast-feed as the women giving birth at the other two hospitals.

hos-pitals may exist in the breast-feeding attitude or infant-feeding counseling practices of the hospital

staff. Reiff and Essock-Vitale7 suggested that “hos-pital staff and routines exerted a stronger influence

on mothers’ infant-feeding practices by nonverbal

teaching (the hospital ‘modeling’ of infant formula

products) than by verbal teaching (counseling

sup-porting breast feeding).” This implies that hospital

staff and routines, centered around a

formula-feed-ing mode, can by suggestion influence maternal infant-feeding behavior. These nonverbal hospital

routines may be responsible for the observed differ-ences in exclusive breast-feeding rates between hos-pitals.

The longer a mother waited to initiate breast-feeding the more likely she was to use formula. Moreover, initiation of breast-feeding and delivery type were significantly correlated (r = .38; P < .05);

so that women who had a cesarean delivery tended

to initiate breast-feeding in the later postpartum hours. The cesanean delivery rates varied by hos-pital (lowest at the university hospital), as did the

proportion of women initiating breast-feeding

dun-ing the first 6 postpartum hours (highest at the university hospital). This finding indicates that the

rising cesarean delivery rate in the United States’#{176}

may indirectly promote formula use by delaying

initiation of breast-feeding.

Ideally, the hospital environment is conducive to the successful establishment of lactation. Often, however, the hospital routine is organized around a bottle-feeding mode, which can adversely affect breast-feeding.”2 Hospital practices that increase mother-neonate contact and increase the frequency of breast-feeds should have a positive effect on establishment of lactation, minimizing breast prob-lems such as engorgement, and ultimately increase the duration of breast-feeding. The findings of 5ev-eral studies support these hypotheses. Interviews with 100 mothers after delivery revealed that the sooner the neonate was put to the breast, the earlier lactation was established.’3 In addition, the earlier a first feed and the more frequent the number of feeds, the longer the duration of breast-feeding.’4

The maternal breast-feeding commitment was evaluated by examining when the mother made the decision to breast-feed and her planned duration of breast-feeding. The maternal anticipated duration of breast-feeding had no effect on formula use. Interestingly, 39% of these first-time mothers were unsure of how long they would breast-feed, which

indicates that breast-feeding continuation for many

women is guided by their experience with the method. In contrast, women who made the decision to breast-feed before rather than during or after

pregnancy were significantly more likely to

breast-feed exclusively.

Ethnicity was not associated with exclusive

breast-feeding in the final multivariate model. The

apparent ethnic differences were largely accounted for by hospital factors and timing of the decision to breast-feed. For example, 41% ofblack compared with 72% of white women initiated breast-feeding in the first 6 postpartum hours; 37% of black vs 19% of white women breast-fed on a schedule; and

35% black vs 51% of white women decided to

breast-feed before pregnancy.

In summary, delivery at the university hospital and early initiation of breast-feeding were strong indicators of exclusive breast-feeding, which im-plies that hospital factors can affect the early in-fant-feeding pattern and may influence long-term successful breast-feeding. Hospital staff should be aware that their breast-feeding attitude, infant-feeding counseling practices, and specific hospital

routines may play a large role in promoting on

inhibiting exclusive breast-feeding.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a contract from the National Institute of Child Health and Human

Devel-opment of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda,

Maryland.

We recognize and appreciate Survey Research Associ-ates, mc, for conducting the field work in completion of the study and particularly Sandi Eznine and Anna Martin

for their work in coordinating the project. We also appre-ciate the George Washington University Medical Center,

Prince George’s General Hospital and Medical Center, and the Washington Hospital Center. We particularly

thank Maureen Edwards, MD, William F. Peterson, MD,

and Elaine LoGuidice, RN.

REFERENCES

1. Kurinij N, Shiono PH, Rhoads GG. Breast-feeding incidence and duration in black and white women. Pediatrics. 1988;81:365-371

2. Lawrence RA. Breast-feeding: A Guide for the Medical Profession. 3rd ed. St Louis, MO: CV Mosby Co; 1989 3. Samuels SE, Margen 5, Schoen EJ. Incidence and duration

of breast-feeding in a health maintenance organization pop-ulation. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;42:504-510

4. Wright HJ, Walker PC. Prediction of duration of breast feeding in primiparas. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 1983;37:89-94

5. Loughlin HH, Clapp-Channing NE, Gehlbach SH, Pollard JC, McCutchen TM. Early termination of breast-feeding-identifying those at risk. Pediatrics. 1985;75:508-513

6. Samuels SE. Socio-cultural obstacles to breastfeeding in an American community: the role of formula supplementation. Paper presented at the American Public Health Association Annual Meeting; November 1981; Los Angeles, CA 7. Reiff ML, Essock-Vitale SM. Hospital influences on early

infant-feeding practices. Pediatrics. 1985;76:872-879

9. Dixon WJ. BMDP Statistical Software. Berkeley, CA: Uni- lating ‘breast is best’ from theory to practice. Am J Obstet

versity of California Press; 1983:330-344 GynecoL 1980;138:105-117

10. Shiono PH, Fielden JG, McNellis D, Rhoads GG, Pearse 13. Mercer J, Russ R. Variables affecting time between child-WH. Recent trends in cesarian birth and trial of labor rates birth and the establishment of lactation. J Gen Psychol.

in the US. JAMA. 1987;257:494-497 1980102155-156

1 1. Johnson CA. Breast-feeding skills for health professi?nals. 14. Salariya EM Easton PM Cater JI. Duration of breast

A workshop at the American Public Health Association . . . . .

Annual Meeting; November 1981; Los Angeles, CA feeding after early initiation and frequent feeding. Lancet. 12. Winikoff B, Baer EC. The obstetrician’s opportunity: trans- 1978;2:11411143

NOTICE

REGARDING

THE

AMERICAN

ACADEMY

OF PEDIATRICS

NUTRITION

AWARD

1992

Nominations for the 1992 AAP Nutrition Award are now being solicited.

Separate letters should be written for each individual nominated. The letter

should contain a description of the nominee’s achievements and state clearly

the basis for the recommendation (including references to the literature which

describes his/her work). It is requested that the nominee’s bibliography be

submitted with the nominating letter, together with copies of available reprints.

Letters supporting the nomination (no more than five) are to be solicited and screened by the nominator and forwarded to the attention of:

Edgar 0. Ledbetter, MD, Director

Department of Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health

American Academy of Pediatrics

141 Northwest Point Boulevard

P0 Box 927

Elk Grove Village, IL 60009-0927

Please note that the deadline for award nominations is December 14, 1991. The Academy appreciates your effort to assist in the appropriate selection of a deserving person for this award.

NUTRITION

AWARD

STIPULATIONS

The Nutrition Award of the American Academy of Pediatrics was established in 1944. The award is made possible by a grant from the Infant Formula Council.

The Nutrition Award provides an honorarium of $3000 to be awarded under

the following stipulations:

1. The award will be made for outstanding achievement in research relating to

the nutrition of infants and children.

2. That the award be made for research, which has been completed and publicly

reported.

3. That the award be made for research, conducted by residents of the United

States and Canada.

4. That the award be made to one individual or for one project.

5. The award is open to all regardless of age. In fact, it is hoped that younger

persons will be considered for the award. No current member of the

Com-mittee on Nutrition shall be eligible for the award.

The Nutrition Award also includes round trip tourist class airfare as well as two days lodging at $150 per diem for the recipient and another person of his/ hen choice to attend the Annual Meeting of the Academy.