Instruments to Detect Alcohol and Other Drug Misuse

in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review

abstract

CONTEXT:Alcohol and other drug (AOD) misuse by youth is a significant public health concern. Unanticipated treatment for AOD-related mor-bidities is often sought in hospital emergency departments (EDs). Screening instruments that rapidly identify patients who require fur-ther diagnostic evaluation and/or brief intervention are critically important.

OBJECTIVE:To summarize evidence on screening instruments that

can assist emergency care clinicians in identifying AOD misuse in pe-diatric patients.

METHODS:Fourteen electronic databases (including Medline, Embase,

and PsycINFO) and reference screening were used. Psychometric and prospective diagnostic studies were selected if the instrument focused on detecting AOD misuse in patients aged 21 years or younger in the ED. Two reviewers independently assessed quality and extracted data. Va-lidity and reliability data were collected for psychometric studies. In-strument performance was assessed by using sensitivity, specificity, and positive (LR⫹) and negative (LR⫺) likelihood ratios. Meta-analysis was not possible because of clinical and measurement heterogeneity.

RESULTS:Of the 1545 references initially identified, 6 studies met in-clusion criteria; these studies evaluated 11 instruments for universal or targeted screening of alcohol misuse. Instruments based on diag-nostic criteria for AOD disorders were effective in detecting alcohol abuse and dependence (sensitivity: 0.88; specificity: 0.90; LR⫹: 8.80) and cannabis use disorder (sensitivity: 0.96; specificity: 0.86; LR⫹: 6.83).

CONCLUSIONS:On the basis of the current evidence, we recommend

that emergency care clinicians use a 2-question instrument for detect-ing youth alcohol misuse and a 1-question instrument for detectdetect-ing cannabis misuse. Additional research is required to definitively an-swer whether these tools should be used as targeted or universal screening approaches in the ED.Pediatrics2011;128:e180–e192

AUTHORS:Amanda S. Newton, PhD, RN,a,b,cRebecca

Gokiert, PhD,c,dNeelam Mabood, MD, MSc,aNicole Ata,

MD,aKathryn Dong, MD, MSc, FRCP(C),e,fSamina Ali,

MDCM, FRCP(C),a,c,gBen Vandermeer, MSc,hLisa Tjosvold,

MLIS,hLisa Hartling, PhD,a,hand T. Cameron Wild, PhDb,i

Departments ofaPediatrics,bPsychiatry, andeEmergency Medicine andhAlberta Research Centre for Health Evidence, Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, dCommunity-University Partnership for the Study of Children,

Youth, and Families, Faculty of Extension, andiSchool of Public Health, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada; cWomen and Children’s Health Research Institute, Edmonton,

Alberta, Canada;fEmergency Department, Royal Alexandra Hospital, Alberta Health Services, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada; andgPediatric Emergency Department, Stollery Children’s Hospital, Alberta Health Services, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

KEY WORDS

substance abuse detection, screening, adolescent, emergency medical services

ABBREVIATIONS

AOD—alcohol and other drug ED—emergency department

DSM—Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

QUADAS—Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies LR—likelihood ratio

AUDIT—Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test AUDIT-C—Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test—consumption subscale

DISC—Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children

Dr Ata’s current affiliation is School of Public Health, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Ms Tjosvold’s current affiliation is JohnW. Scott Health Sciences Library, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2010-3727

doi:10.1542/peds.2010-3727

Accepted for publication Mar 18, 2011

Address correspondence to Amanda S. Newton, PhD, RN, Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, 8213 Aberhart Centre One, 11402 University Ave, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2J3. E-mail: mandi.newton@ualberta.ca

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright © 2011 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

Alcohol and other drug (AOD) misuse is typically initiated and escalated during adolescence and peaks during early adulthood. By grade 12, up to 57% of American and Canadian youth report having consumedⱖ5 drinks on 1 occa-sion.1,2 Other drugs including

canna-bis, cocaine, amphetamines, and ec-stasy are typically tried by the ages of 13 or 14 years1 and may be used

throughout adolescence.2Comparable

results have been obtained with other national and state/provincial surveys; the critically important implication is that early onset of AOD misuse is a strong predictor of later dependence or abuse (14.6% lifetime prevalence for substance-use disorders; median age of onset: 20 years)3–6and

persis-tent dysfunction.7

The morbidity and mortality associ-ated with AOD misuse is well estab-lished.8–10 Accidents and injuries

oc-curring to youth while intoxicated are common and can be fatal.11,12Between

2001 and 2003, 16% of all youth in-hospital deaths in Canada13and 6% of

youth deaths in the United States14

re-sulted from alcohol-related trauma. In 2002, 2% of hospitalizations in Canada for morbidity associated with illicit drug use were by children younger than 14 years; this statistic increased eightfold for persons aged 15 to 29 years.8 Mental health morbidities

as-sociated with AOD misuse include post-traumatic stress,15,16antisocial

behav-iors,17 and intentional self-harm.18

Other consequences include dating vi-olence, delinquent behavior, and un-planned (and often unprotected) sex-ual intercourse.19–21

Youth who misuse alcohol respond to treatment.22Youth who misuse 1 drug

(eg, cannabis only) respond better to treatment compared with those who engage in polysubstance misuse,23

which suggests that earlier interven-tion (ie, when youth are only misusing/ abusing 1 substance) might be

benefi-cial. Many youth do not seek help for AOD misuse because they may not rec-ognize their use as being problem-atic,24may not know where to seek

as-sistance,25or may be embarrassed to

ask for help.26The emergency

depart-ment (ED) may provide a critical and unique opportunity to initiate care that targets AOD misuse at the time of a substance-related consequence.27The

public health approach to identifying and managing substance misuse us-ing screenus-ing, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) is widely advocated in a number of clinical set-tings28including the ED.29In 2010, the

American Academy of Pediatrics rec-ommended that physicians routinely screen and evaluate youth for sub-stance misuse.30 In the ED, however,

routine approaches to screening, treatment, and follow-up recommen-dations vary.29A more definitive

knowl-edge base on screening for AOD mis-use specific to the ED setting may assist in standardizing which screen-ing component of SBIRT is most appro-priate for this clinical population, es-pecially in relation to strategies and outcomes associated with the brief-intervention component of SBIRT. The objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the psychometric proper-ties and accuracy of instruments aimed at detecting AOD misuse in pedi-atric and young adult patients who present to the ED.

METHODS

Search Strategies

We developed and implemented sys-tematic search strategies by using lan-guage (English and French) and year (1985–2010) restrictions. This review was part of a series of reviews aimed at examining the available evidence for pediatric emergency mental health and addictions care31,32; therefore, a

much broader search strategy was used initially to identify all relevant

ED-based mental health studies. After the initial search, more-focused strategies were used to identify relevant primary

studies for this review’s objective. The search was conducted in 14 high-yield electronic databases: Medline, Ovid Medline In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Ovid HealthStar, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Health Technol-ogy Assessment Database, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, ACP

Journal Club, PsycINFO, Cumulative In-dex to Nursing and Allied Health Liter-ature (CINAHL), SocIndex, ProQuest Theses and Dissertations, and Child Welfare Information Gateway.

Because of diagnostic changes be-tween the Diagnostic and Statistical Manuals(DSMs) from 1980 (DSM-III) to 1987 (DSM-III-R) in classifying sub-stance misuse (drug abuse, subsub-stance abuse, substance dependence), we

made an a priori decision to exclude diagnostic studies published before 1985 that were identified in our hand search of reference lists and key jour-nals. The original search was con-ducted in January 2008 and updated in March 2009 and October 2010. The final Medline strategy is provided in Appen-dix 1; comprehensive strategies used in each database are available from

the corresponding author on request.

To identify unpublished and in-progress studies, we searched Clini-calTrials.gov and contacted authors of relevant studies. We also reviewed

Study Selection

The search results were screened in-dependently by at least 2 of 4 possible reviewers (Dr Ata, Dr Mabood, Hansen Zhou, and Kyra Klein). The full articles of potentially relevant studies were re-trieved if screened as relevant by at least 1 of the reviewers; these articles were later confirmed independently for inclusion or exclusion. We included studies at the screening and inclusion/ exclusion stages if the authors at-tempted to establish reliability, valid-ity, or accuracy of instruments designed to yield diagnostic informa-tion; focused on AOD-involved youth aged 19 years or younger who were seeking ED care; and reported reliabil-ity and validreliabil-ity data (psychometric studies) or prospective sensitivity and specificity data (diagnostic studies). We made a posthoc decision to include studies that predominantly included our age range (indicated by reported mean age) but extended into early adulthood (up to 21 years), given that the study authors had deemed the in-strument appropriate for younger youth. Each study was confirmed inde-pendently for inclusion by 2 of 4 re-viewers (Dr Ata, Dr Mabood, Hansen Zhou, and Kyra Klein).

Assessment of Quality

Methodologic quality for all studies was assessed by 2 reviewers (Drs Ata and Mabood). Disagreements were re-solved through discussion and consen-sus with a third reviewer (Dr Newton). Psychometric studies were evaluated on report of external and internal va-lidity by using a modified version of the Downs and Black assessment,33

cre-ated specifically to assess the rigor of psychometric studies (see Supplemen-tal Fig 2). This modified assessment tool was developed by 2 research team members (Drs Newton and Gokiert), and interrater reliability34was

deter-mined during quality assessment. The

quality of diagnostic studies was as-sessed by using the Quality Assess-ment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS) checklist.35,36 Using this

checklist, we defined our reference standard as patients diagnosed with alcohol and/or substance misuse or dependence according to DSM-III-R37or

DSM-IV38criteria. Using the QUADAS, we

also rated studies on the clarity of their methodologic description for the studied diagnostic test (termed “index test”), the time frame between the ref-erence standard and the index test, and whether interpretation of the ref-erence standard and index test were blinded.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted by using a stan-dardized form that assessed study characteristics (eg, language of publi-cation, country), characteristics of the study population, study setting, instru-ment description and reference stan-dard (diagnostic studies only), and re-sults. Data were extracted by 1 reviewer (Dr Mabood) and checked for accuracy and completeness by a sec-ond reviewer (Dr Ata). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. In the case of unclear or unreported infor-mation in the original studies, primary authors were contacted.

Data Analysis

Validity and reliability data were re-viewed for psychometric studies with the aim of determining each instru-ment’s measurement ability. These data were compared with diagnostic data to assess the clinical perfor-mance of each instrument. Clinical het-erogeneity in the patient population and instruments precluded the use of meta-analysis to pool and interpret di-agnostic studies. Individual didi-agnostic instrument performance was as-sessed by using sensitivity-specificity analysis. These statistics were either taken directly from the articles or

computed from other data given within the article. Ninety-five percent confi-dence intervals were also computed when possible. We calculated positive (LR⫹) and negative (LR⫺) likelihood ra-tios to provide estimates on how screening cut scores change the odds of a diagnosis. The LR⫹expressed the strength of evidence available to “rule in” a AOD-use diagnosis, whereas the LR⫺indicated whether a AOD-use diagnosis could be “ruled out.” General guidelines for interpreting LR⫹values to rule in a disorder are:⬎10, strong evidence; 5 to 10, modest evidence; 2 to 5, weak evidence; and 0.5 to 2, no sig-nificant change in the likelihood of a disorder. General guidelines for inter-preting LR⫺values to rule out a disor-der are: 0.2 to 0.5, weak evidence; 0.1 to 0.2, modest evidence; and⬍0.1, strong evidence.39 Thus, in this review we

aimed to identify instruments with large LR⫹and small LR⫺values.

RESULTS

Description of Included Studies

Figure 1 shows the flow of studies through the selection process. The search strategies identified 1545 stud-ies (after removal of duplicates) as po-tentially relevant to AOD misuse among youth presenting to the ED. Of these studies, 117 were identified as poten-tially relevant through abstract screening, and 6 studies met inclusion criteria after full-text review; studies that included both psychometric and diagnostic evaluations40,41 and those

with only a psychometric42,43 or

diag-nostic44,45 focus were included. For 1

diagnostic study there were multiple publications.41,46Across the 6 studies,

con-ducted in the United States. Study populations generally included compa-rable numbers of male and female

par-ticipants (range: 37%– 60% male), and ages ranged from 12 to 21 years. There was substantial variation in which youth were recruited from the ED into the various studies. Some studies re-cruited all comers, whereas others limited inclusion to only those youth who presented with an injury or psy-chiatric complaint. No study recruited youth who only presented to the ED with an AOD-related complaint. The variation in ED presentations under-scored the differences in instrument

intent/use across studies and limited direct comparisons of instruments in this review.

Methodologic Quality

Psychometric Studies

Interrater reliability, according to the

modified tool for quality assessment, was excellent (⫽ 0.87). No psycho-metric studies met all methodologic criteria to indicate highest quality; gaps were observed across all studies. Of the 4 psychometric studies, repre-sentativeness of the study population was limited in 1 study,42blinding

dur-ing results interpretation was not re-ported from any study,40–43 and

com-prehensive reporting of instrument reliability was absent from 3 stud-ies.40,42,43Three studies also lacked

in-terpretation of instrument

responsive-ness (eg, degree to which the

instrument can discriminate between symptoms),40,42,43 2 studies provided

limited interpretability to their results (eg, the meaning that can be derived from the instrument’s score),41,42and 2

studies did not address instrument ac-ceptability (eg, responder/administra-tor burden, the number of missing re-sponses, reports of refusal rates),42,43

thereby reducing the ability to assess the instrument’s clinical utility.

1511 records identified through database searching after duplicates removed

1545 records screened 34 records identified through other sources

1428 records excluded on the basis of abstract (n = 1423), unable to locate/retrieve (n = 5)

117 full-text articles assessed for eligibility

110 full-text articles that did not meet inclusion criteria on the basis of study design,

clinical focus, clinical population

6 studies (in 7 publications) included in qualitative synthesis: Psychometric and diagnostic design (n = 2)

Psychometric design (n = 2) Diagnostic design (n = 2)

FIGURE 1

Selection of studies.

TABLE 1 Clinical Instruments for the Identification of AOD Use (N⫽11)

AUDIT Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test CAGE Cut down, Annoyed, Guilty, Eye-opener CRAFFT Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble

DISC cannabis symptoms Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children: cannabis symptoms

DSM-IV 2-item scale (1) Alcohol abuse (drinking in hazardous situations); (2) Alcohol dependence FAST Fast Alcohol Screening Test

RAFFT Relax, Alone, Friends, Family, Trouble

RAPS4-QF Remorse, Amnesia/blackouts, Perform, Starter/eye-opener, Quantity, Frequency

RBQ Reckless Behavior Questionnaire

RUFT-Cut Riding with a drinking driver, Unable to stop, Family/Friends, Trouble, Cut down

Diagnostic Studies

Using the QUADAS tool, the diagnostic studies scored highly for reporting. One study45 met all tool dimensions

for clarity of its methodologic de-scription of the index test, indication of the time frame between the refer-ence standard and the index test, and blinding during reference-standard and index-test interpreta-tion. The remaining studies satisfied the majority of tool dimensions with the exception of a lack of clarity of blinding during results interpreta-tion40,41,44 and unclear methods

re-lated to test administration.44

Reliability and Validity of

Instruments for Detecting AOD Use in the ED

Across 4 studies, 8 instruments were psychometrically evaluated among heterogeneous samples of youth pre-senting to the ED (Table 2). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AU-DIT) was consistently used across studies; the reliability and validity of other instruments were evaluated in relation to the AUDIT. No studies exam-ined psychometric properties of

in-struments designed to measure drug misuse other than alcohol. Of the stud-ies included in our review, the majority of author groups initially published psychometric work and went on to publish diagnostic investigations that used the same instrument (Table 3). The evaluation of psychometric

prop-erties focused on factor structure (ie, an instrument’s dimensions),40,42

internal consistency (ie, a within-instrument form of reliability assess-ment indicating how well different items comprising an instrument con-sistently assess the instrument’s di-mensions),41,43and validity (ie, the

ex-tent to which an instrument measures what it is intended to measure)41,43

(Table 2).

In an evaluation of the AUDIT’s con-sumption subscale (AUDIT-C) (3 ques-tions) among youth presenting to the ED with injuries, Chung et al40reported

high factor loadings for the 3 subscale items (item 1, 0.70; item 2, 0.83; item 3, 0.94) and internal consistency of the consumption subscale (␣⫽.85) that indicate similarity in item measure-ment of “consumption.” Kelly et al42

re-ported similar findings between items (factor loadings: item 1, 0.77; item 2, 0.80; item 3, 0.98) and examined inter-nal consistency in a later publication47

(␣⫽ .81). In terms of overall instru-ment performance, Kelly et al42

demon-strated good model fit,47,48 which

suggests that instrument items cohe-sively measured consumption/conse-quences, and Chung et al40reported

re-sults that approached good model fit (Table 2). The AUDIT subscale that

rep-resents alcohol dependence and con-sequences was also examined by both studies by using 740 and 642 AUDIT

items, but factor loadings and internal consistency reliability varied in each study (Table 2).

Internal consistency of the AUDIT was compared with other instruments in 2 studies by Kelly et al,41,43and criterion

validity (ie, an instrument’s ability to identify the criterion of hazardous

ver-sus nonhazardous drinking in youth) was examined in another study by Kelly et al.43 In 1 investigation, the AUDIT-C

demonstrated superior internal con-sistency (␣⫽.81) to the CRAFFT (Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble)

TABLE 3 Characteristics of Diagnostic Studies That Evaluated Instruments That Screen for AOD Use

Author (Year)

Quality, QUADAS Score (of 14)

Instrument Reference Standard

Participants

Sample,n

(% Male)

Age Range (Mean), y

ED Presentation

Kelly et al41,46

(2009 and 2004)

12 AUDIT-C DSM-IV AUD

diagnosis

181 (57) 18–20 (NR) Any (excluding severe illness or injury)a

FAST RAPS4-QF RUFT-Cut CRAFFT DSM-IV 2-item Chung et al44

(2003)

11 DISC cannabis symptoms DSM-IV CUD diagnosis

442 (60) 13–19 (15.7) Injury (not alcohol-positive at time of ED visit)

AUDITb

RBQb

Chung et al40

(2002)

12 AUDITb DSM-IV AUD

diagnosis

173 (57) 13–19 (16.4) Injury (not alcohol-positive at the time of ED visit; reported alcohol use in the previous year)

Bastiaens et al45(2000)

14 RAFFT DSM-IV SUD

diagnosis

226 (55) 13–18 (15.4) Required psychiatric assessmentc

FAST indicates Fast Alcohol Screening Test; RAPS4-QF, Remorse, Amnesia/blackouts, Perform, Starter/eye-opener, Quantity, Frequency; RUFT-Cut, Riding with a drinking driver, Unable to stop, Family/Friends, Trouble, Cut down; CRAFFT, Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble; AUD, alcohol-use disorder (abuse or dependence); NR, not reported; SUD, substance-use disorder (dependence or abuse to at least 1 substance); CUD, cannabis-use disorder (abuse or dependence); RBQ, Reckless Behavior Questionnaire; RAFFT, Relax, Alone, Friends, Family, Trouble. aThirty-six percent of the sample was diagnosed with an AUD.

(␣⫽.61), Fast Alcohol Screening Test (␣⫽.64), RAPS4-QF (Remorse, Amne-sia/blackouts, Perform, Starter/eye-opener, Quantity, Frequency) (␣ ⫽ .68), RUFT-Cut (Riding with a drinking driver, Unable to stop, Family/Friends, Trouble, Cut down) (␣ ⫽ .64), and a 2-item DSM-IV screen (␣⫽.41).41In

an-other study, the full AUDIT instrument demonstrated superior internal con-sistency (␣ ⫽ .88) compared with 2 other instruments: the TWEAK (Toler-ance, Worried, Eye-opener, Amnesia, Kut-down) (␣ ⫽ .50) and CAGE (Cut down, Annoyed, Guilty, Eye-opener) (␣⫽.66). There was a substantial cor-relation between the full-scale AUDIT and TWEAK total scores (r⫽0.83;P⬍ .001), which suggests that both of them effectively identified hazardous and nonhazardous drinking, and the AUDIT demonstrated a more distinct scoring difference43(Table 2).

Diagnostic Accuracy of Instruments to Detect AOD Use in the ED

Prospective, diagnostic evaluation compared 10 AOD-use instruments with a DSM-IV reference standard for alcohol-, substance-, or cannabis-use disorders (Table 3). All instruments were evaluated in a general clinical population, as opposed to a population with known AOD misuse. The use of 2 diagnostic items based on DSM-IV cri-teria (“In the past year, have you some-times been under the influence of alco-hol in situations where you could have caused an accident or gotten hurt?” and “Have there often been times when you had a lot more to drink than you in-tended to have?”) were more effective than other instruments in detecting alco-hol abuse and dependence (sensitivity⫽ 0.88; specificity⫽0.90).41Youth who

re-ceived a score of 1 (of 2) on the 2 items (answering yes to at least 1 question)

had a more than eightfold likelihood of being diagnosed with a related disorder (the LR⫹approached strong evidence to rule in a disorder) (Table 4). Compared with other instruments, use of a Diag-nostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) question for previous-year can-nabis use (“How often in the past year have you used cannabis?”) was the most effective for detecting a cannabis-use disorder (sensitivity ⫽ 0.96; specificity⫽0.86).44There was an

almost sevenfold likelihood of being di-agnosed with a cannabis-use disorder if use was reportedⱖ2 times over the previous year (modest evidence to rule in a disorder) (Table 4).

Discrepant results were found in 2 studies with different cut-score rec-ommendations for the AUDIT to identify problematic drinking in a heteroge-neous clinical population. Kelly et al41

recommended a cut score of 6 (of 12)

TABLE 4 Accuracy of Instruments That Screen for AOD Use

Author (Year)

Instrument Study Recommended Cut Score (Score Range)

or Recommended Item

Sensitivity (95% CI)

Specificity (95% CI)

LR⫹ (95% CI)

LR⫺ (95% CI)

Interpretation

Kelly et al41,46

(2009 and 2004)

AUDIT-C Cut score⫽6 (0–12) 0.74 (NR) 0.77 (NR) 3.22 (NR) 0.34 (NR) The DSM-IV 2-item was an effective general screen for identifying alcohol use disorders in youth; evidence to rule in and rule out an alcohol-use disorder was modest FAST Cut score⫽3 (0–16) 0.83 (NR) 0.73 (NR) 3.07 (NR) 0.23 (NR)

RUFT-Cut Cut score⫽3 (0–11) 0.80 (NR) 0.68 (NR) 2.50 (NR) 0.29 (NR) CRAFFT Cut score⫽3 (0–6) 0.69 (NR) 0.73 (NR) 2.56 (NR) 0.42 (NR) RAPS4-QF Cut score⫽3 (0–6) 0.79 (NR) 0.72 (NR) 2.82 (NR) 0.29 (NR) DSM-IV 2-item Cut score⫽1 (0–2) 0.88 (NR) 0.90 (NR) 8.80 (NR) 0.13 (NR)

Chung et al44

(2003)

DISC cannabis symptoms

Previous-year frequency of cannabis use (ⱖ2 times)

0.96 (0.88–0.99) 0.86 (0.82–0.89) 6.83 (5.31–8.80) 0.05 (0.02–0.16) 1 DISC question acted as an effective general screen for identifying cannabis-use disorders in youth; evidence to rule in and rule out an alcohol-use disorder was modest Modified AUDIT Cut score⫽3 (0–40) 0.70 (0.58–0.81) 0.82 (0.78–0.86) 3.90 (2.99–5.09) 0.36 (0.25–0.53)

Modified RBQ Perceived risk of cannabis use (pretty to very risky)a

0.88 (0.74–0.96) 0.67 (0.62–0.72) 2.66 (2.1–3.20) 0.18 (0.08–0.41)

Chung et al40

(2002)

Modified AUDIT AUDIT-C cut score⫽3 (0–12)

0.89 (0.80–0.95) 0.74 (0.64–0.82) 3.42 (2.44–4.81) 0.15 (0.08–0.29) The AUDIT resulted in weak evidence to rule in and rule out an alcohol-use disorder

AUDIT alcohol-related problems subscale cut score⫽1 (0–16)

0.83 (0.73–0.91) 0.64 (0.54–0.73) 2.32 (1.75–3.07) 0.26 (0.15–0.44)

Bastiaens et al45(2000)

RAFFT 2 positive answers 0.89 (0.82–0.94) 0.69 (0.60–0.77) 2.89 (2.19–3.83) 0.16 (0.09–0.27) Positive answers to 2 RAFFT items resulted in weak evidence to rule in and rule out an alcohol-use disorder

CI indicates confidence interval; FAST, Fast Alcohol Screening Test; RUFT-Cut, Riding with a drinking driver, Unable to stop, Family/Friends, Trouble, Cut down; CRAFFT, Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble; RAPS4-QF, Remorse, Amnesia/blackouts, Perform, Starter/eye-opener, Quantity, Frequency; NR, not reported; RBQ, Reckless Behavior Questionnaire; RAFFT, Relax, Alone, Friends, Family, Trouble.

when using the AUDIT-C (3 questions) (sensitivity⫽0.74; specificity⫽0.77), whereas Chung et al40recommended a

cut score of 3 (of 12) when using the AUDIT-C (sensitivity ⫽ 0.89; specific-ity⫽0.74) and a cut score of 1 (of 16) when using 4 questions on the alcohol-related problems subscale (sensitiv-ity ⫽ 0.83; specificity ⫽ 0.64). Using these different cut scores, there was a similar threefold increase in the likeli-hood of a youth being diagnosed with an alcohol-use disorder (LR⫹ with weak evidence to rule in a disorder). Other instruments evaluated in the ED demonstrated similar diagnostic accu-racy for identifying alcohol-use disor-ders (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

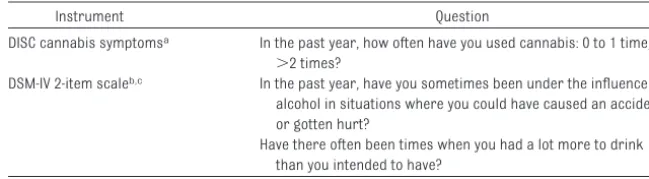

Universal screening for AOD misuse among youth who present to the ED is both clinically and developmentally ap-propriate and is sanctioned/recom-mended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. For youth with known substance-use disorders, targeted screening may facilitate the delivery of brief interventions to them before the onset of more severe problems. On the basis of the evidence in this review, we recommend 2 measures for emer-gency care clinicians at this time: a 2-question instrument derived from DSM-IV criteria for detecting probable alcohol misuse and a 1-question in-strument (DISC) for detecting proba-ble cannabis misuse (Taproba-ble 5). Both of these recommended instruments can be used as a “quick screen” in the ED to identify those youth who have a high likelihood of having an alcohol- or cannabis-use disorder and who re-quire further comprehensive diagnos-tic/clinical workup for diagnosis in a non-ED setting. Youth who answer “yes” to at least 1 of 2 DSM-IV screen questions have an eightfold risk of hav-ing an alcohol-use disorder, whereas youth who report cannabis use more than 2 times over the previous year on

the DISC have an almost sevenfold risk of having a cannabis-use disorder. Al-though the most extensively evaluated instrument across studies, the AUDIT, demonstrated superior psychometric properties compared with the DSM-IV screen, the different recommended cutoff scores limit the instrument’s di-agnostic role with youth in the ED at this time. In contrast, the low inter-nal consistency of the DSM-IV screen in comparison to the AUDIT is not viewed as an instrument limitation at this time; it is an expected reflection of the instrument’s 2 items that mea-sure complementary but distinct di-mensions of alcohol use (abuse and dependence).

In general, different diagnostic ap-proaches and varied findings across studies in this review indicate that this field of study still requires maturation and refinement. A universal screening approach was used in the majority of studies and involved screening for misuse in all comers in a general pedi-atric ED population,40–44whereas a

tar-geted approach in 1 study involved screening ED patients in need of fur-ther psychiatric assessments.45 No

studies identified in this review used screening instruments to target youth who presented to the ED with an AOD-related complaint, which is a targeted approach commonly used in the adult literature. Whether screening should involve a select group of youth with an ED visit related to AOD use or be

ap-plied to all youth who might benefit from further diagnostic evaluation should be clarified in future research. As a first step, higher-performing in-struments identified in this review should be evaluated further to define the impact that universal and targeted screening approaches in the ED have on subsequent service access (whether in the ED or in referral to other health services), diagnosis, and youth health outcomes, which may in-dicate which approach is most effec-tive for the ED setting. Additional psy-chometric evaluation to determine interrater reliability would also help to assess the degree to which different clinicians using the same instrument yield consistent scores. Without a firm evidence-based backing, it is unlikely that screening (universal or targeted) will be widely adopted by emergency care clinicians.

Defining minimally acceptable thresh-olds for instrument sensitivity/speci-ficity and LRs to rule in/rule out disor-ders is also needed. In the ED, screening instruments that have max-imum sensitivity and specificity and strong evidence to rule in/rule out substance-use disorders should be de-sired. Such instruments combined with minimum implementation time and ease of use can provide clinicians with critical clinical information in a short amount of time to guide further assessment. Instruments with low specificity and modest-to-weak

evi-TABLE 5 Recommended Instruments for ED Use

Instrument Question

DISC cannabis symptomsa In the past year, how often have you used cannabis: 0 to 1 time,

⬎2 times?

DSM-IV 2-item scaleb,c In the past year, have you sometimes been under the influence of

alcohol in situations where you could have caused an accident or gotten hurt?

Have there often been times when you had a lot more to drink than you intended to have?

aData source: Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan M, et al.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(7):865– 877.

bQuestions are based on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) to reflect DSM-IV criteria. Scoring: no, 0; yes, 1; total score ranges from 0 to 2.

dence to rule in/rule out disorders, such as many identified in this review, do not have ideal performance charac-teristics for the ED setting and are not endorsed at this time. An important weakness of these instruments is their potential to incorrectly identify a substance-use disorder in a youth. The potential for undue stress and harm for youth and their families caused by an inaccurate screening instrument should be weighed against whether this is an acceptable risk/hazard dur-ing instrument use.

LIMITATIONS

Several limitations of this systematic review stem from the available evi-dence base. Heterogeneity in instru-ment evaluation across the studies precluded comprehensive between-study comparisons including meta-analysis. Psychometric studies did not examine interrater reliability to fur-ther establish the instrument utility in the ED. Other limitations were the lack of blinding during data interpretation in diagnostic studies and an unclear independence between the

refer-ence standard and instrument under evaluation. Several of the diagnostic studies should be interpreted with caution, because they may have over-estimated instrument accuracy; these studies included our recom-mended instruments.40,41,44These

is-sues may be particularly salient for diagnostic-based screening items in which items may be similar to refer-ence standard items. Another limita-tion of this review relates to the lim-ited research to date on identifying appropriate clinical instruments de-signed to measure the spectrum of pedi-atric AOD misuse (including other drug and polysubstance use) in the ED.

CONCLUSIONS

On the basis of this review, we recom-mend that emergency care clinicians universally use a 2-question DSM-IV screen for detecting youth alcohol mis-use and a 1-question instrument for cannabis misuse in the ED. These in-struments can be used as a “quick screen” to identify those youth who have a higher likelihood of exhibiting substance-use disorders that require

further diagnostic evaluation, brief in-tervention, and, if appropriate, refer-ral to specialty treatment. Whether tar-geted screening approaches might be the more efficient/beneficial/cost-effective approach in the ED remains to be determined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this project was provid-ed by Knowlprovid-edge Synthesis grant 200805KRS (to Dr Newton), awarded from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr Newton holds a CIHR reer Development Award from the Ca-nadian Child Health Clinician Scientist Program in partnership with the Sick-Kids Foundation, Child & Family Re-search Institute (British Columbia), Women & Children’s Health Research In-stitute (Alberta), Manitoba InIn-stitute of Child Health. Dr Wild is a Health Scholar with Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions.

We acknowledge the important contri-butions of Ms Kyra Klein and Mr Han-sen Zhou (Department of Pediatrics, University of Alberta) for assisting with study screening.

REFERENCES

1. Statistics Canada. Youth Smoking Survey 2006 – 07. Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: Uni-versity of Waterloo/Statistics Canada; 2008 2. Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE.Monitoring the Future: Na-tional Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2004. Volume I: Secondary School Stu-dents. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2005

3. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime preva-lence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbid-ity survey replication.Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593– 602

4. Bonomo YA, Bowes G, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Patton GC. Teenage drinking and the onset of alcohol dependence: a cohort study over seven years. Addiction. 2004;99(12): 1520 –1528

5. Viner RM, Taylor B. Adult outcomes of binge drinking in adolescence: findings from a UK national birth cohort.J Epidemiol Commu-nity Health. 2007;61(10):902–907

6. D’Amico EJ, Ellickson PL, Collins RL, Martino S, Klein DJ. Processes linking adolescent problems to substance-use problems in late young adulthood.J Stud Alcohol. 2005; 66(6):766 –777

7. Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Klein DN, Andrews JA, Small JW. Psychosocial func-tioning of adults who experienced sub-stance use disorders as adolescents. Psy-chol Addict Behav. 2007;21(2):155–164 8. Popova S, Rehm J, Patra J, Baliunas D,

Tay-lor B. Illegal drug-attributable morbidity in Canada 2002.Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26(3): 251–263

9. Sussman S, Skara S, Ames SL. Substance abuse among adolescents.Subst Use Mis-use. 2008;43(12–13):1802–1828

10. Clark DB, Martin CS, Cornelius JR. Youth-onset substance use disorders predict young adult mortality.J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(6):637– 639

11. Hingson RW, Heeren T, Jamanka A, Howland J. Age of drinking onset and unintentional

injury involvement after drinking.JAMA. 2000;284(12):1527–1533

12. Hingson RW, Zha W. Age of drinking onset, alcohol use disorders, frequent heavy drinking, and unintentionally injuring one-self and others after drinking.Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):1477–1484

13. Canadian Institute for Health Information. National trauma registry. Available at: http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/dispPage. jsp?cw_page⫽services_ntr_e. Accessed February 16, 2010

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol-attributable deaths and years of poten-tial life lost: United States, 2001.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(37):866 – 870 15. Clark DB, Neighbors B. Adolescent

sub-stance abuse and internalizing disorders.

Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 1996;5(1): 45–57

a d u l t s . A d d i c t B e h a v. 2 0 0 6 ; 3 1 ( 1 1 ) : 2094 –2104

17. Lewis CE, Bucholz KK. Alcoholism, antisocial behavior and family history.Br J Addict. 1991;86(2):177–194

18. Cherpitel CJ, Moskalewicz J, Swiatkiewicz G. Drinking patterns and problems in emer-gency services in Poland.Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39(3):256 –261

19. Champion H, Wagoner K, Song EY, Brown VK, Wolfson M. Adolescent date fighting victim-ization and perpetration from a multi-community sample: associations with sub-stance use and other violent victimization and perpetration.Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2008;20(4):419 – 429

20. Poulin C, Graham L. The association be-tween substance use, unplanned sexual in-tercourse and other sexual behaviours among adolescent students. Addiction. 2001;96(4):607– 621

21. Ellickson PL, McGuigan KA, Adams V, Bell RM, Hays RD. Teenagers and alcohol misuse in the United States: by any definition, it’s a big problem.Addiction. 1996;91(10):1489 –1503 22. Tripodi SJ, Bender K, Litschge C, Vaughn MG. Interventions for reducing adolescent alco-hol abuse: a meta-analytic review.Arch Pe-diatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(1):85–91 23. Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro

TM, Powers MB, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders.Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):179 –187

24. D’Amico EJ. Factors that impact adoles-cents’ intentions to utilize alcohol-related prevention services.J Behav Health Serv Res. 2005;32(3):332–340

25. Klein DJ, McNulty M, Flatau CN. Adolescents’ access to care.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152(7):676 – 682

26. Cunningham JA, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, A g r a w a l S , T o n e a t t o T . B a r r i e r s t o treatment: why alcohol and drug abusers delay or never seek treatment.Addict Be-hav. 1993;18(3):347–353

27. Burke PJ, O’Sullivan J, Vaughan BL. Youth substance use: brief interventions by emer-gency care providers.Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21(11):770 –776

28. Babor TF, McRee BG, Kassebaum PA, et al. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT): toward a public

health approach to the management of sub-stance abuse.Subst Abus. 2007;28(3):7–30 29. Cunningham RM, Bernstein SL, Walton M, et

al. Alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs: future directions for screening and intervention in the emergency department.Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(11):1078 –1088

30. American Academy of Pediatrics, Commit-tee on Substance Abuse. Alcohol use by youth and adolescents: a pediatric concern.

Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):1078 –1087 31. Newton AS, Hamm MP, Bethell J, et al.

Pedi-atric suicide-related presentations: a sys-tematic review of mental health care in the emergency department.Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(6):649 – 659

32. Hamm MP, Osmond M, Curran J, et al. A sys-tematic review of crisis interventions used in the emergency department: recommen-dations for pediatric care and research. Pe-diatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(12):952–962 33. Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of

creat-ing a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–384

34. Altman DG.Practical Statistics for Medical Research.London, United Kingdom: Chap-man and Hall; 1991

35. Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in system-atic reviews.BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003; 3:25

36. Mann R, Hewitt CE, Gilbody SM. Assessing the quality of diagnostic studies using psy-chometric instruments: applying QUADAS.

Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009; 44(4):300 –307

37. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnos-tic and StatisDiagnos-tical Manual of Mental Disor-ders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psy-chiatric Association; 1987

38. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnos-tic and StatisDiagnos-tical Manual of Mental Disor-ders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psy-chiatric Association; 1994

39. Sloane PD, Slatt LM, Ebell MH, Jacques LB, Smith MA.Essentials of Family Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2008

40. Chung T, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Monti PM. Alcohol use disorders identification test: Factor structure in an adolescent emer-gency department sample.Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26(2):223–231

41. Kelly TM, Donovan JE, Chung T, Bukstein OG, Cornelius JR. Brief screens for detecting al-cohol use disorder among 18 –20 year old young adults in emergency departments: comparing AUDIT-C, CRAFFT, RAPS4-QF, FAST, RUFT-Cut, and DSM-IV 2-Item Scale. Addict Behav. 2009;34(8):668 – 674

42. Kelly TM, Donovan JE. Confirmatory factor analyses of the Alcohol Use Disorders Iden-tification Test (AUDIT) among adolescents treated in emergency departments.J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62(6):838 – 842

43. Kelly TM, Donovan JE, Kinnane JM, Taylor DM. A comparison of alcohol screening in-struments among under-aged drinkers treated in emergency departments.Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37(5):444 – 450

44. Chung T, Colby SM, O’Leary TA, Barnett NP, Monti PM. Screening for cannabis use dis-orders in an adolescent emergency depart-ment sample.Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003; 70(2):177–186

45. Bastiaens L, Francis G, Lewis K. The RAFFT as a screening tool for adolescent substance use disorders.Am J Addict. 2000;9(1):10 –16 46. Kelly TM, Donovan JE, Chung T, Cook RL, Del-bridge TR. Alcohol use disorders among emergency department-treated older adolescents: a new brief screen (RUFT-Cut) using the AUDIT, CAGE, CRAFFT, and RAPS-QF.

Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(5):746 –753 47. Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit

in-dexes in covariance structure analysis: con-ventional criteria versus new alternatives.

Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55 48. Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of

assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, eds. Testing Structural Equation Models.

Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993:136 –162 49. Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan M, et al. The NIMH

Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-2): description, acceptability, preva-lences and performance in the MECA study.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996; 35(7):865– 877

APPENDIX 1 Search Strategy: Medline (1950 to October 12, 2010)

1. suicide/

2. “self-injurious behavior”/ 3. alcoholism/di, pc 4. Alcohol drinking/pc

5. exp “substance related disorders”/di, pc, rh

6. (substance abuse adj (detection or education or counsel$)).mp. 7. exp substance abuse detection/

8. crisis intervention/ or “crisis care”.ti,ab. 9. “mental health triage”.mp.

10. exp Mental Disorders/di, pc, rh, th

11. (motivational interview* or brief intervention or brief motivational interview).ti,ab. 12. (crafft or audit or raps).ti,ab.

13. “alcohol use disorders identification test”.ti,ab. 14. “rapid alcohol problems screen”.ti,ab. 15. agression.mp.

16. (restraint or restraining).ti,ab. 17. hallucinat*.ti,ab.

18. or/1–7,10–17 19. Suicide Attempted/ 20. exp Mental Disorders/

21. (“alcohol or other drugs” or “alcohol use disorder”).ti,ab. 22. (aud or aod).ti,ab.

23. exp Domestic Violence/ 24. or/19–23

25. Mass Screening/ or Survival Analysis/ or Risk/ or Incidence/ or Risk Factors/ or “Social Work Department, Hosptial”/ or “social services”.mp.

26. “Referral and Consultation”/ or exp Counseling/ or “Behavior Therapy”/ 27. di.fs.

28. exp Screeing test/ or (marker* or detect* or assess* or probability or likelihood or accuracy or diagnos*).mp.

29. (sensitivity or specificity).mp. 30. or/27–29

31. 24 and 30 32. 18 or 31

33. exp Emergency Service, Hospital/ 34. emergency medical services/ 35. exp emergencies/

36. “HOSPITAL EMERGENCY SERVICE”.mp. 37. (ED or PED or emergenc*).tw.

38. (EDs and (emergency or emergencies)).mp.

39. ((emergenc$ or trauma) adj5 (departmen$ or ward$ or service$ or unit$ or room$ or hospital$ or care or patient$ or physician$ or doctor$ or medicine or treatment$)).mp.

40. (emergency or emergencies or trauma).jn. 41. exp Emergency Medicine/

42. or/ 33–41 43. 32 and 42

44. emergency services, psychiatric/ or behavioral emergency.ti,ab. 45. or/43–44

46. limit 45 to (clinical trial, all or comparative study or controlled clinical trial or evaluation studies or guideline or journal article or meta analysis or multicenter study or practice guideline or randomized controlled trial or “review” or “scientific integrity review” or technical report or twin study or validation studies)

APPENDIX 2 Instrument Description Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)a

Domain: hazardous alcohol use (consumption subscale) 1. How often do you have a drink containing alcohol?

Scoring: never (0), monthly or less (1), 2–4 times/mo (2), 2–3 times/wk (3), 4 or more times/wk (4) 2. How many drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day when you are drinking?

Scoring: 1 or 2 (0), 3 or 4 (1), 5 or 6 (2), 7 to 9 (3), 10 or more (4) 3. How often do you have 6 or more drinks on 1 occasion?

Scoring: never (0), less than monthly (1), monthly (2), weekly (3), daily or almost daily (4) Domain: dependence symptoms

4. How often during the last year have you found that you were not able to stop drinking once you had started?

Scoring: never (0), less than monthly (1), monthly (2), weekly (3), daily or almost daily (4) 5. How often during the last year have you failed to do what was normally expected of you because of

drinking?

Scoring: never (0), less than monthly (1), monthly (2), weekly (3), daily or almost daily (4) 6. How often during the last year have you needed a drink in the morning to get yourself going after a

heaving drinking session?

Scoring: never (0), less than monthly (1), monthly (2), weekly (3), daily or almost daily (4) Domain: harmful alcohol use (alcohol-related problems subscale)

7. How often during the last year have you had a feeling of guilt or remorse after drinking? Scoring: never (0), less than monthly (1), monthly (2), weekly (3), daily or almost daily (4) 8. How often during the last year have you been unable to remember what happened the night before

because of your drinking?

Scoring: never (0), less than monthly (1), monthly (2), weekly (3), daily or almost daily (4) 9. Have you or someone else been injured because of your drinking?

Scoring: no (0), yes but not in the last year (2), yes during the last year (4)

10. Has a relative, friend, doctor, or other health care worker been concerned about your drinking or suggested you cut down?

Scoring: no (0), yes but not in the last year (2), yes during the last year (4) Scoring range: 0 to 4; total score ranges from 0 to 40

CAGEb

C⫽Have you ever felt that you should CUT down on your drinking? A⫽Have people ANNOYED you by criticizing your drinking? G⫽Have you ever felt bad or GUILTY about your drinking?

E⫽Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover (EYE-OPENER)?

Scoring: no (0), yes (1); total score ranges from 0 to 4 CRAFFTc

C⫽Have you ever ridden in a CAR driven by someone (including yourself) who was “high” or had been using alcohol or drugs?

R⫽Do you ever use alcohol or drugs to RELAX, feel better about yourself, or fit in? A⫽Do you ever use alcohol or drugs to while you are by yourself, ALONE? F⫽Do you ever FORGET things you did while using alcohol or drugs?

F⫽Do your family or FRIENDS ever tell you that you should cut down on your drinking or drug use? T⫽Have you ever gotten into TROUBLE while you were using alcohol or drugs?

Scoring: no (0), yes (1); total score ranges from 0 to 6 Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC)d

Cannabis items

1. Have you used any cannabis in the last 6 mo? “yes”/“no” or “sometimes”/“somewhat” 2. Past year frequency of cannabis use: 0 to 1 time,⬎2 times

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM, version IV) criteria for alcohol abuse or dependencee,f

1. In the past year, have you sometimes been under the influence of alcohol in situations where you could have caused an accident or gotten hurt?

2. Have there often been times when you had a lot more to drink than you intended to have? Scoring: no (0), yes (1); total score ranges from 0 to 2

Fast Alcohol Screening Test (FAST)g

1. How often do you have 6 or more drinks (women)/8 or more drinks (men) on 1 occasion? Scoring: never (0), less than monthly (1), monthly (2), weekly (3), daily or almost daily (4) 2. How often during the last year have you failed to do what was normally expected of you because of

drinking?

Scoring: never (0), less than monthly (1), monthly (2), weekly (3), daily or almost daily (4) 3. How often during the last year were you unable to remember what happened the night before

because you had been drinking?

Scoring: never (0), less than monthly (1), monthly (2), weekly (3), daily or almost daily (4) 4. In the last year has a relative or friend, or a doctor or other health care worker been concerned

about your drinking or suggested you cut down?

APPENDIX 2 Continued

RAFFTh

R⫽Do you drink/drug to RELAX, feel better about yourself or fit in? A⫽Do you ever drink/drug while you are by yourself, ALONE? F⫽Do your closest FRIENDS drink/drug?

F⫽Does a close FAMILY member have a problem with alcohol/drugs? T⫽Have you ever gotten into TROUBLE from drinking/drugging?

Scoring: no (0), yes (1); total score ranges from 0 to 5 RAPS4-QFi

R⫽During the last year have you had a feeling of guilt or remorse after drinking? (Remorse) A⫽During the last year has a friend or family member ever told you about things you said or did

while you were drinking that you could not remember? (Amnesia/blackouts)

P⫽During the last year have you failed to do what was normally expected of you because of drinking? (Perform)

S⫽Do you sometimes take a drink in the morning when you first get up? (Starter/eye-opener) Q⫽During the last year have you had 5 or more drinks (4 or more for women) on at least 1 occasion?

(Quantity)

F⫽During the last year did you have a drink as often as once a month? (Frequency) Scoring: no (0), yes (1); total score ranges from 0 to 6

Reckless Behavior Questionnaire (RBQ)j

Responses include never, once, 2–5 times, 6–10 times, and⬎10 times 1. Driven while under the influence of alcohol.

2. Had sex without using contraceptives (withdrawal and having sex at a “safe” time of the menstrual cycle doesn’t count as contraception)

3. Damaged or destroyed public or private property 4. Used marijuana

5. Shoplifted

6. Driven a car at over 80 miles per hour 7. Had sex with someone you didn’t know well 8. Used cocaine

9. Driven⬎20 miles per hour over the speed limit 10. Used illegal drugs other than marijuana or cocaine

Scoring: (1) “not at all risky” to (5) “very risky”; total score ranges from 10 to 50 RUFT Cutk

R⫽Riding with a drinking driver no (0), yes (1)

U⫽(cannot) Unable to stop drinking

never (0), less than monthly (1), monthly (2), weekly (3), daily or almost daily (4) F⫽Family/Friends concerned about drinking

no (0), yes but not in the last year (2), yes during the last year (4) T⫽getting into Trouble as a result of drinking

no (0), yes (1) Cut⫽need to Cut down

no (0), yes (1)

Scoring: mixed scale; total score ranges from 0 to 11. TWEAKl

T⫽How many drinks does it take to make you feel high (TOLERANCE)?

Scoring: consuming 3 or more drinks to feel the effects of alcohol (2), consuming fewer than 3 drinks to feel the effects of alcohol (0)

W⫽Have close friends or relatives worried or complained about your drinking in the past year (WORRIED)?

E⫽Do you sometimes have a drink in the morning when you first get up (EYE-OPENER)?

A⫽Has a friend or family member ever told you about things you said or did while you were drinking that you could not remember (AMNESIA)?

K⫽Do you sometimes feel the need to cut down on your drinking (KUT-DOWN)? Scoring: no (0), yes (1); total scale score ranges from 0 to 7

aData source: Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG.The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test:

Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001.

bData source: Ewing JA.JAMA. 1984;252(14):1905–1907.

cData source: Knight JR, Shrier LA, Bravender TD, et al.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(6):591–596. dData source: Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan M, et al.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(7):865– 877. eData source: Vinson DC, Kruse RL, Seale JP.Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(8):1392–1398.

fQuestions are based on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) to reflect DSM-IV criteria. gData source: Hodgson RJ, Alwyn T, John B, Thom B, Smith A.Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37(1):61– 66. hData source: Bastiaens L, Francis G, Lewis K.Am J Addict. 2000;9(1):10 –16.

iData source: Cherpitel CJ.J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61(3):447– 449.

jData source: Shaw DS, Wagner EF, Arnett J, Aber MS.J Youth Adolesc. 1992;21(3):305–323.

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2010-3727 originally published online June 6, 2011;

2011;128;e180

Pediatrics

Samina Ali, Ben Vandermeer, Lisa Tjosvold, Lisa Hartling and T. Cameron Wild

Amanda S. Newton, Rebecca Gokiert, Neelam Mabood, Nicole Ata, Kathryn Dong,

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/128/1/e180 including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/128/1/e180#BIBL This article cites 42 articles, 4 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/emergency_medicine_ Emergency Medicine

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2010-3727 originally published online June 6, 2011;

2011;128;e180

Pediatrics

Samina Ali, Ben Vandermeer, Lisa Tjosvold, Lisa Hartling and T. Cameron Wild

Amanda S. Newton, Rebecca Gokiert, Neelam Mabood, Nicole Ata, Kathryn Dong,

Department: A Systematic Review

Instruments to Detect Alcohol and Other Drug Misuse in the Emergency

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/128/1/e180

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/suppl/2011/05/27/peds.2010-3727.DC1 Data Supplement at:

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.