ARTICLE

Prospective Study of Infantile Hemangiomas:

Clinical Characteristics Predicting Complications

and Treatment

Anita N. Haggstrom, MDa, Beth A. Drolet, MDb, Eulalia Baselga, MDc, Sarah L. Chamlin, MDd, Maria C. Garzon, MDe, Kimberly A. Horii, MDf,

Anne W. Lucky, MDg, Anthony J. Mancini, MDd, Denise W. Metry, MDh, Brandon Newell, MDf, Amy J. Nopper, MDf, Ilona J. Frieden, MDa

aDepartment of Dermatology, University of California, San Francisco, California;bDepartment of Dermatology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; cDepartment of Dermatology, Hospital de la Santa Creu I Sant Pau, Barcelona, Spain;dDepartments of Pediatrics and Dermatology, Northwestern University Feinberg

School, of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois;eDepartments of Dermatology and Pediatrics, Columbia University, New York, New York;fSection of Dermatology, Children’s Mercy

Hospital and Clinics, Kansas City, Missouri;gDivision of Pediatric Dermatology and the Hemangioma and Vascular Malformation Center, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital,

Cincinnati, Ohio;hDepartment of Dermatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES.Infantile hemangiomas are the most common tumor of infancy. Risk

factors for complications and need for treatment have not been studied previously in a large prospective study. This study aims to identify clinical characteristics associated with complications and the need for therapeutic intervention.

PATIENTS AND METHODS.We conducted a prospective cohort study at 7 US pediatric

dermatology clinics with a consecutive sample of 1058 children, agedⱕ12 years, with infantile hemangiomas enrolled between September 2002 and October 2003. A standardized questionnaire was used to collect data on each patient and each hemangioma, including clinical characteristics, complications, and treatment.

RESULTS.Twenty-four percent of patients experienced complications related to their

hemangioma(s), and 38% of our patients received some form of treatment during the study period. Hemangiomas that had complications and required treatment were larger and more likely to be located on the face. Segmental hemangiomas were 11 times more likely to experience complications and 8 times more likely to receive treatment than localized hemangiomas, even when controlled for size.

CONCLUSIONS.Large size, facial location, and/or segmental morphology are the most

important predictors of poor short-term outcomes as measured by complication and treatment rates.

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/ peds.2006-0413

doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0413

All authors are members of the Hemangioma Investigator Group.

Key Words

dermatology, hemangioma, birthmark, infantile hemangioma

Abbreviations

IH—infantile hemangioma CI— confidence interval OR— odds ratio

Accepted for publication Apr 10, 2006

Address correspondence to Ilona J. Frieden, MD, Department of Dermatology, 3rd Floor, 1701 Divisadero St, San Francisco, CA 94143. E-mail: friedenij@derm.ucsf.edu

I

NFANTILE HEMANGIOMAS (IHs) are classically consid-ered “birthmarks,” but unlike most birthmarks, they are uniquely dynamic. At birth they are either absent or barely evident, but they proliferate in the first few weeks to months of life, followed by an involution phase over several months to years. Most IHs are uncomplicated, but a significant minority involve complications, includ-ing ulceration, threat to vision, airway obstruction, and congestive heart failure. Hemangiomas can also leave residual scarring and/or permanent distortion of facial anatomic landmarks, which can be truly life altering.1–3 Given the wide spectrum of disease and the natural tendency for involution, the greatest challenge in caring for infants with hemangiomas is predicting which in-fants need treatment or are at highest risk for complica-tions. A primary aim of this study was to identify specific clinical features that are most predictive of complications and/or need for treatment.METHODS

Study Design

The Hemangioma Investigator Group prospectively en-rolled patients with IH over a 13-month period, between September 2002 and October 2003. Patients/guardians provided signed informed consent, and institutional re-view boards at each participating site approved the study protocol. Eligible patients included those who wereⱕ12 years at the time of enrollment and who hadⱖ1 IH in any stage of evolution. A consecutive sample was en-rolled by each investigator. A total of 1096 patients, of whom 1058 were US patients, were enrolled during this 13-month period, and clinical follow-up continued until June 2004. For the purposes of this report, data were analyzed from US sites only. Using standardized

com-puter-scannable forms, investigators collected informa-tion about patient gender, ethnicity, prematurity, birth weight, maternal/paternal age, prenatal testing proce-dures, placental abnormalities, maternal illnesses, smok-ing, recreational drug use and medication history, and family history. The location, size, and morphologic sub-type forⱕ4 hemangiomas per patient were noted. Mor-phologic subtypes were localized, segmental, indetermi-nate, and multifocal (Fig 1).4“Segmental hemangiomas” were those hemangiomas or clusters of hemangiomas with a configuration corresponding to a recognizable and/or significant portion of a developmental segment. “Localized hemangiomas” were defined as those hem-angiomas that seem to grow from a single focal point or were localized to an area without any apparent linear or developmental configuration. “Indeterminate hemangi-omas” were those that were not readily classified as either localized or segmental, and “multifocal hemangi-omas” were defined as ⱖ10 cutaneous hemangiomas. Two investigator training sessions and a study manual helped insure uniformity of subtype classification, and interrater reliability was then tested and found to be excellent using astatistic (data not shown).

The size of each hemangioma was measured using a “hemispherical measurement.” Using a flexible tape measure, the surface of the hemangioma was measured in the 2 perpendicular directions using the maximum diameter in each to obtain a final measurement (cubic centimeters). Treatment and complications incurred be-fore and during the study period were noted (Table 1). The study period extended for a minimum of 8 months and up to 23 months after enrollment to maximally capture morbidities during hemangioma proliferation. Follow-up visits were scheduled according to clinical

FIGURE 1

need, and follow-up forms recording hemangioma char-acteristics, treatment, and complications were completed by study investigators. Treatment decisions were deter-mined by physicians caring for the patient and not al-tered for purposes of this study.

Statistical Analysis

Data were processed by the National Outcomes Center, where forms were scanned into a computer database. Information was manually verified. Data analysis was performed in conjunction with the National Outcomes Center and the University of California San Francisco Biostatistics Department.2tests andttests were used to

compare categorical variables and continuous variables, respectively. Spearman rank correlation, Mann-Whitney rank sum, and Kruskal-Wallis statistical methods were used when appropriate. Random-effects logistic regression models were used to address potential confounders.

RESULTS

A total of 1915 hemangiomas were observed in 1058 patients (mean: 1.8; median: 1.0). The majority (68.8%) of patients had a solitary hemangioma, and 97% of patients had ⱕ6 hemangiomas. Detailed clinical infor-mation was recorded for each hemangioma, except when patients had ⬎4 hemangiomas, in which case information was only recorded for the 4 most clinically significant hemangiomas.

The detailed clinical characteristics of a total of 1530 hemangiomas were documented using hemangioma-specific intake forms. Approximately 41% (630; 41.2%) were located on the face. Involvement of other sites was as follows: head and neck, excluding the face in 322 (21.0%), trunk in 357 (23.3%), extremities in 281 (18.4%), and perineum in 94 (6.1%). Uncommonly, some hemangiomas extended into⬎1 site (for example: face, neck, and chest). The majority of hemangiomas were classified as localized (1022; 66.8%), whereas 200 (13.1%) were segmental, 253 (16.5%) were indetermi-nate, and 55 (3.6%) were multifocal. The mean size of an individual hemangioma was 18.9 cm2 (SD ⫾66.7)

with a median of 3.6 cm2(95% confidence interval [CI]:

3.3– 4.0 cm2). Hemangiomas ranged from pinpoint

le-sions (⬍0.004 cm2) to 1320 cm2. Facial hemangiomas

averaged 19.9 cm2 (95% CI: 14.7–25.0 cm2).

Twenty-two percent (136 of 630) of facial hemangiomas were segmental.

Complications that occurred before enrollment (based on parental recall and/or medical charts) and during the study period were recorded (Table 1). Before enrollment, 299 patients (28.3%) had complications; 255 patients (24.1%) experienced complications during the study period. During the study period, ulceration was the most common complication noted in 168 pa-tients (16.0%); threat to vision (59; 5.6%), airway ob-struction (15; 1.4%), auditory canal obob-struction (6; 0.6%), and cardiac compromise (4; 0.4%) were seen less commonly. Hepatic hemangiomas were detected in 10 patients (0.1%), but routine abdominal imaging was not performed as a part of this study protocol.

Treatment before and during enrollment was re-corded. Some form of treatment was administered in 269 patients (25%) before enrollment, and 402 (38%) received therapy during the study period. During the study period, patients received systemic steroids (130; 12.3%), intralesional steroids (43; 4.1%), topical ste-roids (103; 9.8%), wound care for ulceration (145; 13.7%), oral antibiotics (21; 2.0%), pulsed dye laser (84; 8.0%), and excisional surgery (60; 5.7%). Rarely, inter-feron (1 patient) and vincristine (3 patients) were used. Some patients received⬎1 mode of therapy. The most common indications for treatment were disfigurement (33.1%), ulceration (19.8%), and rapid growth (16.5%).

Factors Predicting Complications and/or Treatment

Size, location, and subtype were major factors that pre-dicted complications and/or need for treatment. The mean size of hemangiomas experiencing any complica-tion (including ulceracomplica-tion and bleeding, visual compro-mise, auditory canal obstruction, cardiac comprocompro-mise, and airway obstruction) was 37.3 cm2(95% CI: 30.36 –

44.2 cm2) compared with 19.1 cm2(95% CI: 14.4 –23.9

cm2) for hemangiomas without complications.

Compli-cated hemangiomas were, on average, 18.1 cm2larger

than uncomplicated hemangiomas (P⬍.0001; 95% CI: 11.5–24.7 cm2). Hemangiomas complicated by surface

ulceration or bleeding had a mean size of 40.4 cm2; the

observed difference between ulcerated and nonulcerated hemangiomas was 20.1 cm2(P⬍.0001; 95% CI: 12.3–

28.1 cm2). For every 10-cm2 increase in hemangioma

size, there was a 5% increase in the likelihood of expe-riencing a complication (odds ratio [OR]: 1.051; P ⬍ .05). Hemangiomas that received treatment of any type (including systemic therapy, wound care, laser, ad sur-gical excision) had a mean size of 30.4 cm2, which was

11.1 cm2larger than those that did not receive treatment

(P⬍ .0001; 95% CI: 5.7–16.5 cm2). Hemangiomas

re-quiring oral corticosteroid treatment were 21.2 cm2

larger than those that did not receive treatment (P ⬍ .0001; 95% CI: 12.0 –30.4 cm2). For each 10-cm2

in-TABLE 1 Complications in Study Patients

Complication No. (%) of Study Patients

Ulceration 245 (23.2)

Visual compromise 73 (6.9)

Airway obstruction 19 (1.8)

Auditory canal obstruction 12 (1.1)

Cardiac compromise 4 (0.4)

crease in hemangioma size, there was a 3.9% increase in the likelihood of treatment (OR: 1.039;P⬍.05).

Morphologic subtype was the best single predictor of complications and need for treatment. The influence of hemangioma size and subtype on the need for treatment and development of complications was studied, using a random-effects logistic model. Controlling for hemangi-oma size, hemangihemangi-oma subtype was a strong predictor for development of complications and need for treat-ment. Segmental hemangiomas were 8 times more likely to receive treatment compared with localized hemangi-omas after controlling for hemangioma size (OR: 8.4; 95% CI: 5.8 –12.2). Similarly, segmental hemangiomas were 11 times more likely to develop complications (in-cluding ulceration, bleeding, visual compromise, audi-tory compromise, cardiac compromise, or airway ob-struction) than localized hemangiomas after controlling for size (OR: 11.5; 95% CI: 7.8 –17.0). When comparing outcomes between subtypes, segmental hemangiomas consistently had higher rates of complications and treat-ment compared with indeterminate and localized hem-angiomas (Table 2). Indeterminate hemhem-angiomas had rates of complication and treatment higher than local-ized but lower than segmental hemangiomas. The effect of subtype was even more important on the face. Com-plication and treatment rates varied by location of hem-angioma (Table 3). Facial hemhem-angiomas experienced complications 1.7 times as often as nonfacial hemangi-omas (OR: 1.7; 95% CI: 1.3-2.3;P⫽.0002). Hemangi-omas located on the face were 3.3 times more likely to receive some form of treatment, including systemic ther-apy, wound care, and pulsed dye laser, when compared with nonfacial hemangiomas (OR: 3.3; 95% CI: 2.6-4.3; P⬍.0001). Demographic and perinatal factors, includ-ing gender, ethnicity, prematurity, birth weight, family history, and maternal chronic illness, did not predict increases in complications or the need for treatment.5

DISCUSSION

Physicians evaluating infants with hemangiomas face a challenge. Virtually all IHs involute spontaneously, and most do so without sequelae, but a sizeable minority have complications or need treatment. In this study, 24% had complications during the study period, and 38% received some form of therapeutic intervention. A major goal of this, the largest prospective study of IH,

was to determine which clinical features are most pre-dictive of morbidity and/or need treatment. In attempt to capture the broadest spectrum of the disease, enroll-ment included all of the children with hemangiomas seen at enrolling sites, even if they were found inciden-tally on children being seen for other dermatologic con-ditions. Because enrollment was exclusively in pediatric dermatology practices, with most patients being referred specifically for IH, we assume that the complication and treatment rates are higher than would be seen by pri-mary care physicians, but they are lower than those reported by surgical practices, where an estimated 40% to 60% experienced complications or are anticipated to require corrective surgery.6,7We would not expect refer-ral bias to impact the actual clinical features in our cohort that predicted poor outcome. The relatively short-term follow-up duration (minimum 8 to maxi-mum 21 months) of the study precluded a true estimate of rates of scarring and/or anatomic distortion leading to permanent disfigurement, but this concern is high-lighted by the fact that perceived risk of disfigurement was the leading indication for treatment (33%). A pro-spective study lasting 4 to 5 years or longer would be best to fully capture this risk. In this study, patients who were determined to have uncomplicated hemangiomas by the study investigators were not routinely seen in follow-up, which could potentially result in the under-estimation of complication rates if unexpected compli-cations were not reported to study investigators.

Morphologic Subtype as a Predictor of Complication and/or Treatment

Although both size and location are important predic-tors, the greatest single predictor of prognosis is morpho-logic subtype. Segmental hemangiomas were 11 times more likely to develop complications than localized hemangiomas, even after controlling for size, and they had a much greater need for treatment. This result af-firms the findings of 2 previous retrospective studies.4,8 Although not the focus of this article, facial segmental hemangiomas can also be associated with extracutane-ous malformations, especially the PHACE association9 and visceral hemangiomas.10Their propensity for ulcer-ation is clearly established in this study (33.5% vs 7.2% for localized), but the reasons for this are not clear. Segmental hemangiomas are believed to arise from an

TABLE 2 Complication of Hemangiomas by Subtype

Hemangioma Subtype

No. of Hemangiomas per Subtype

No. (%) of Hemangiomas Experiencing Complications

No. (%) of Hemangiomas Receiving Treatment

Localized 1022 98 (9.6) 197 (19.3)

Segmental 200 111 (55.5) 132 (66.0)

Indeterminate 253 63 (24.9) 104 (41.1)

Multifocal 55 5 (9.1) 5 (9.1)

error in development occurring early in gestation11–13 and conceivably have more pervasive tissue dysregula-tion, making them more prone to tissue breakdown, but this is purely conjecture.

Unfortunately, the classification of hemangiomas by morphologic subtype may be difficult for physicians who do not see large numbers of infants with hemangiomas, and some may feel unsure about their ability to recog-nize what actually constitutes a segmental hemangioma (Fig 1).13The concept of an anatomic territory defining a risk, however, is not new to physicians. Examples in-clude dermatomal distribution maps (eg, for port-wine stains and herpes zoster) and maps defining the lines of Blaschko (mapping epidermal nevi, incontinentia pig-menti, and other mosaic disorders). Such patterns, al-though initially unfamiliar, become much easier to rec-ognize once the viewer is cognizant of their existence and appearance, even in cases where they are only partially manifest, as is the case with “indeterminate” hemangiomas. These hemangiomas have been shown recently to occur within the boundaries of segmental hemangiomas, suggesting that they are really a forme fruste of segmental hemangiomas.13Therefore, it is not surprising that their rates of morbidity are intermediate between localized and segmental subtypes. Together, segmental and indeterminate hemangiomas comprised less than one third (29.6%) of hemangiomas in the study further emphasizing the large number of lower-risk hemangiomas

Size as a Predictor of Complications and/or Treatment

In addition to morphologic subtype, hemangioma size and location are both highly associated with complica-tions and need for treatment. The median size of hem-angiomas in the study was 3.6 cm2, a size remarkably

smaller than the mean of 18.9 cm2. This discrepancy

reflects the contribution of very large hemangiomas, many of which were 50 to 100 cm2 or larger, which

increased the mean size. It also emphasizes the large number of small, rather innocuous hemangiomas in the study. In contrast, the mean size of hemangiomas with complications was 37.3 cm2, and the mean of those

receiving treatment was 30.4 cm2, numbers which

con-trast significantly with the mean size of those with nei-ther complications (19.2 cm2) nor treatment (19.3 cm2).

Anatomic Location as a Predictor of Complications and/or Treatment

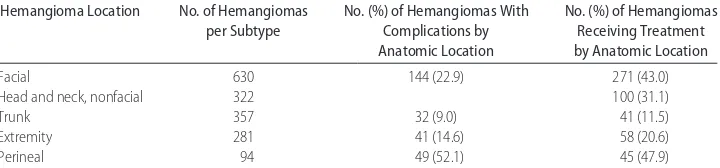

Complication rates and need for treatment varied ac-cording to hemangioma location (Table 3). Perineal hemangiomas had the highest rate of complications (52%) in our study, which reflects their propensity for ulceration. The face was the single most common ana-tomic area of involvement (41%), and 43% of facial hemangiomas received treatment of some kind, a rate significantly higher than hemangiomas in other loca-tions. This finding is not surprising given the higher risk for facial hemangiomas impinging on vital structures, such as the eye or nose. Facial hemangiomas also carry a much higher risk of disfigurement than in other sites, because scars are readily visible. Furthermore, soft tissue distortion of the unique three-dimensional structures of the face, even after involution, can lead to permanent deformities.14–19 This fact is underscored by the finding that in fully one third of patients, risk of disfigurement was either the sole indication or one of the indications for treatment. At the same time, it is important to note that more than half of facial hemangiomas did not have complications or receive treatment. Just as important as recognizing which hemangiomas need treatment is rec-ognizing which do not. Although many small, localized hemangiomas on the face, especially those on the lateral areas of the face, may be candidates for observation without treatment, there are still situations when even small and/or localized hemangiomas (especially those on the central face) may need intervention to prevent an-ticipated permanent soft-tissue distortion. Our study was not designed to capture long-term outcomes, and there certainly may have been patients in the cohort who did not receive treatment, yet ended up with some perma-nent sequelae. Further prospective studies are needed to refine our understanding of which smaller hemangio-mas have the greatest potential for causing scars and disfigurement.

Indications for Treatment

Potentially life-threatening morbidities of hemangiomas, such as airway hemangiomas causing obstruction and liver hemangiomas causing high-output cardiac failure, are well-recognized and justifiably feared complications, but these were very uncommon, seen in 1.4% and 0.4%

TABLE 3 Complication of Hemangiomas by Location

Hemangioma Location No. of Hemangiomas

per Subtype

No. (%) of Hemangiomas With Complications by Anatomic Location

No. (%) of Hemangiomas Receiving Treatment by Anatomic Location

Facial 630 144 (22.9) 271 (43.0)

Head and neck, nonfacial 322 100 (31.1)

Trunk 357 32 (9.0) 41 (11.5)

Extremity 281 41 (14.6) 58 (20.6)

Perineal 94 49 (52.1) 45 (47.9)

of our patients, respectively. Sight-threatening heman-giomas were noted in 5.6% of patients. The most fre-quent complication was ulceration, which occurred in 16% of infants during the study period. Ulceration can be very painful and virtually always results in scarring. Treatment of ulceration was the second-most common indication for treatment (19.8%).

CONCLUSIONS

Although the older medical literature has emphasized the benign nature of hemangiomas (except those caus-ing specific medical morbidities), there has been a grow-ing recognition that scarrgrow-ing and disfigurement are real and important morbidities that can be life altering even if not life threatening.20–22This potential is greatest with facial hemangiomas, which, for unknown reasons, are an anatomic site that is disproportionately affected (41% in this study cohort). Information disseminated via the Internet has greatly heightened parental awareness of the potential risk for scarring and can result in undue anxiety even for those hemangiomas that are unlikely to leave scarring. Physicians caring for children with hem-angiomas can expect questions from parents regarding prognosis and, therefore, must understand which hem-angiomas have the greatest risks of complication and need for treatment. Because hemangiomas proliferate rapidly in the first few weeks to months of life, there may be a window of opportunity to intervene in high-risk hemangiomas in an attempt to prevent complica-tions, including permanent scarring. This study should help guide physicians in determining which hemangio-mas may be most appropriate for referral and/or treat-ment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the Dermatology Founda-tion and American Skin AssociaFounda-tion for their funding support.

We thank Dr Nancy Esterly for her inspiration, sup-port, and guidance in developing this study. We also thank our colleagues and staff in the Vascular Anomalies Centers at each institution for their hard work and car-ing for our patients and Alan Bostrom and Charles Mc-Culloch at Biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, and the National Outcomes Center for their database and statistical expertise.

REFERENCES

1. Kim HJ, Colombo M, Frieden IJ. Ulcerated hemangiomas: clin-ical characteristics and response to therapy.J Am Acad Dermatol.

2001;44:962–972

2. Ceisler EJ, Santos L, Blei F. Periocular hemangiomas: what every physician should know. Pediatric Dermatology.2004;21: 1–9

3. Orlow SJ, Isakoff MS, Blei F. Increased risk of symptomatic hemangiomas of the airway in association with cutaneous hemangiomas in a “beard” distribution. J Pediatr.1997;131: 643– 646

4. Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy: clinical characteristics morphologic subtypes and their relation-ship to race ethnicity and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138: 1567–1576

5. Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, Baselga E, et al. A prospective study of infantile hemangiomas, part I: demographic, prenatal and perinatal characteristics.J Pediatr.In press

6. Waner M, Suen JY. The natural history of hemangiomas. In: Waner M, Suen JY, eds.Hemangiomas and Vascular Malformations of the Head and Neck. New York, NY: Wiley-Liss; 1999:13– 46 7. Williams EF 3rd, Stanislaw P, Dupree M, Mourtzikos K, Mihm

M, Shannon L. Hemangiomas in infants and children. An algo-rithm for intervention.Arch Facial Plast Surg.2000;2:103–111 8. Waner M, North PE, Scherer KA, Frieden IJ, Waner A, Mihm

MC Jr. The nonrandom distribution of facial hemangiomas.

Arch Dermatol.2003;139:869 – 875

9. Metry DW, Haggstrom A, Drolet BA, et al. A prospective study of the PHACE association in infantile hemangiomas.Am J Med Genet.2006;140:975–986

10. Metry DW, Hawrot A, Altman C, Frieden IJ. Association of solitary, segmental hemangiomas of the skin with visceral he-mangiomatosis.Arch Dermatol.2004;140:591–596

11. Hersh JH, Waterfill D, Rutledge J, et al. Sternal malformation/ vascular dysplasia association. Am J Med Genet. 1985;21: 177–186, 201–202

12. Weon YC, Chung JI, Kim HJ, Byun HS. Agenesis of bilateral internal carotid arteries and posterior fossa abnormality in a patient with facial capillary hemangioma: presumed incom-plete phenotypic expression of PHACE syndrome.AJNR Am J Neuroradiol.2005;26:2635–2639

13. Haggstrom AN, Lammer EJ, Schneider RA, Marcucio R, Frieden IJ. Patterns of infantile hemangiomas: New clues to hemangioma pathogenesis and embryonic facial development.

Pediatrics.2006;117:698 –703

14. Faguer K, Dompmartin A, Labbe D, Barrellier MT, Leroy D, Theron J. Early surgical treatment of Cyrano-nose haemangio-mas with Rethi incision.Br J Plast Surg.2002;55:498 –503 15. McCarthy, JG, Borud, LJ, Schreiber, JS. Hemangiomas of the

nasal tip.Plastic Reconstruct Surg.2002;109:31– 40

16. Warren SM, Longaker MT, Zide BM. The subunit approach to nasal tip hemangiomas.Plast Reconstr Surg.2002;109:25–30 17. Demiri EC, Pelissier P, Genin-Etcheberry T, Tsakoniatis N,

Mar-tin D, Baudet J. Treatment of facial haemangiomas: the present status of surgery.Br J Plast Surg.2001;54:665– 674

18. Zide BM, Glat PM, Stile FL, Longaker MT. Vascular lip enlargement: Part I. Hemangiomas–tenets of therapy.Plast Re-constr Surg.1997;100:1664 –1673

19. Pitanguy I, Machado BH, Radwanski HN, Amorim NF. Surgical treatment of hemangiomas of the nose.Ann Plast Surg.1996; 36:586 –592

20. Tanner JL, Dechert MP, Frieden IJ. Growing up with a facial hemangioma: parent and child coping and adaptation. Pediat-rics.1998;101:446 – 452

21. Bruckner AL, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy.J Am Acad Dermatol.2003;48:477– 493

22. Mulliken JB, Rogers GF, Marler JJ. Circular excision of hem-angioma and purse-string closure: the smallest possible scar.

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2006-0413

2006;118;882

Pediatrics

Brandon Newell, Amy J. Nopper and Ilona J. Frieden

Garzon, Kimberly A. Horii, Anne W. Lucky, Anthony J. Mancini, Denise W. Metry,

Anita N. Haggstrom, Beth A. Drolet, Eulalia Baselga, Sarah L. Chamlin, Maria C.

Complications and Treatment

Prospective Study of Infantile Hemangiomas: Clinical Characteristics Predicting

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/118/3/882 including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/118/3/882#BIBL This article cites 20 articles, 3 of which you can access for free at:

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2006-0413

2006;118;882

Pediatrics

Brandon Newell, Amy J. Nopper and Ilona J. Frieden

Garzon, Kimberly A. Horii, Anne W. Lucky, Anthony J. Mancini, Denise W. Metry,

Anita N. Haggstrom, Beth A. Drolet, Eulalia Baselga, Sarah L. Chamlin, Maria C.

Complications and Treatment

Prospective Study of Infantile Hemangiomas: Clinical Characteristics Predicting

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/118/3/882

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.