ABSTRACT

By conservative estimates, bipolar disorder affects 2.3 million Americans, and is frequently misdiagnosed, with individuals reporting seeing an average of 4 physicians before receiving the proper diagnosis and treatment. This may be due to the fact that the symptoms of bipolar disorder comprise a mood spectrum, running the gamut from depressive episodes to mania, with periods of euthymia and, in some patients, the simultane-ous expression of both depressive and manic phases simultaneously (mixed mania). Utilizing less cumbersome tools that can be administered by the patients themselves, taking a thorough lon-gitudinal history to avoid missing symptoms of mania or hypomania, along with breakthroughs in the understanding of the genetic, biochemical, and intracellular foundations of affective condi-tions, offer new avenues for the management of this chronic condition.

(Adv Stud Nurs. 2005;3(2):43-48)

A

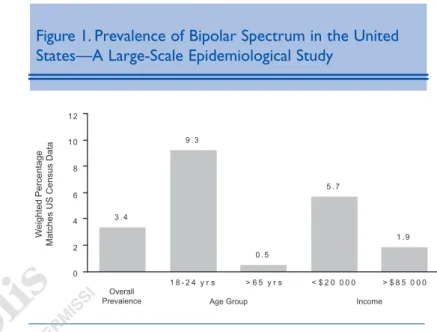

ccording to the National Institute of Mental Health, bipolar disorder affects approximately 2.3 million American adults (age ≥18 years), with an annual prevalence of 1.2% of the population.1-3 Data from Europe, which comprises the complete spectrum of bipolar disorder (including people with bipolar II disorder marked by hypomania), suggests a much higher incidence in the general population, with rates as high as 6.5%.4 Furthermore, Hirschfeld et al developed a screening instrument called the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) and administered it to a population selected to reflect the 2000 census demographics for the United States. Eighty-five thou-sand completed questionnaires were analyzed, reveal-ing a positive MDQ screen rate of 3.7%, suggestreveal-ing that nearly 4% of American adults may suffer from bipolar I and bipolar II disorders.5While it seems to affect both sexes and all races and ethnic groups equal-ly, the MDQ data suggested that young adults and individuals with lower income were at greater risk for this disorder. The prevalence of bipolar disease in this large-scale epidemiologic study among 18 to 24 year olds was 9.3%, reflecting the fact that this condition seems to emerge most often among individuals in their 20s (Figure 1).5 Unfortunately, these findings by Hirschfeld and others showing a higher than expected prevalence of this disorder seem to indicate that this is a condition that may be misdiagnosed frequently. MAKING THEDIAGNOSIS:A CASE OFMISTAKENIDENTITY

Bipolar disorder is a condition that must be diag-nosed by looking at a patient’s history longitudinally, to examine whether there have been periods of mania.

BIPOLAR DISORDER: MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

AND EXPLORING THE BIOLOGICAL ORIGINS

*—

Scott P. Hoopes, MD†

*Based on a presentation given by Dr Hoopes at a sym-posium held in conjunction with the Psychopharmacology for Advanced Practice Psychiatric Nurses Conference.

†Private Practice Psychiatrist, Boise, Idaho.

Address correspondence to: Scott P. Hoopes, MD, 315 N. Allumbaugh, Boise, ID 83704. E-mail: hoopes@cableone.net.

Otherwise, the clinician runs the risk of identifying the condition as unipolar depression (especially if the patient is middle-aged and the manic episodes occurred when the patient was younger), and this has implications for treatment. Additional data from Hirschfeld’s community assessment reveal that 70% of patients who screened positive for bipolar disorder had been misdiagnosed an average of 3.5 times and had consulted physicians 4 times prior to being cor-rectly identified as being bipolar.5Again, not surpris-ingly, most patients were diagnosed as having unipolar depression (60% of cases) followed by anxi-ety disorders (26% of cases) and less commonly as having schizophrenia or borderline personality disor-der (18% and 17% of cases, respectively.) This is most likely due to the presenting symptoms for the person at that point in time, be it depressive symp-toms, anxiety sympsymp-toms, or psychosis—all of which may be associated with bipolar disorder.5

In 2002, Judd et al analyzed prospective data from an ongoing follow-up of 146 patients with bipolar I disorder that had entered the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Depression Study from 1978 through 1981. The patients were followed an average of 12.8 years. Over this period of time, approximately 10% of these patients were either manic or depressed. On average, approximately 50% of the time, they expe-rienced symptoms of depression or mania, even though they may not have met the full diagnostic criteria (Figure 2).6Furthermore, the proportion of patients experiencing depression compared with mania was 3 to 1, indicating that depression is often the most debilitating and painful experience for patients. This poses a challenge in bipolar patients, because treatment with antidepressants may unmask manic episodes, whereas mood stabilizers may not assure euthymia 100% of the time.

DIAGNOSTICCRITERIA FORBIPOLARDISORDER

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV),7bipolar

I disorder is characterized by the occurrence of one or more manic episodes or mixed episodes (see Sidebar). Often, individuals have also had one or more major depressive episodes. To meet the criteria, this mood dis-order cannot be accounted for by the direct effects of a medication, other somatic treatments for depression, drug abuse, toxin exposure, or a general medical

condi-tion, and cannot be better explained as some form of schizophrenia or other psychosis.7

The essential feature of bipolar II disorder is a clin-ical course that is characterized by the occurrence of one or more major depressive episodes accompanied by at least one hypomanic (as opposed to manic)

Figure 1. Prevalence of Bipolar Spectrum in the United States—A Large-Scale Epidemiological Study

Reprinted with permission from Hirschfeld et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in the community.J Clin Psychiatry.2003;64(1):53-59.5

Figure 2. Long-term Frequency of Bipolar Symptoms

Reprinted with permission from Judd et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder.Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(6): 530-537.6

episode. Hypomanic episodes should not be confused with the several days of euthymia that may follow remission of a depressive episode. Like bipolar I disor-der, episodes of substance-induced mood disorder (due to the direct effects of a medication, or other somatic treatments for depression, drug abuse, or toxin exposure) or of mood disorder due to a general medical condition do not count toward a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder. In addition, the episodes cannot be better accounted for by forms of psychosis, such as schizophrenia.7

Mania, according to criteria set forth by the American Psychiatric Association in the DSM-IV, is actually further classified as euphoric mania, mixed mania, or hypomania. A manic episode is a distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated or expansive mood lasting at least a week. During this period, 3 or more specific symptoms (4 or more if the mood is only irritable) must be present: inflated self-esteem or grandiosity, a decreased need for sleep, pres-sured speech, having a flight of ideas or racing thoughts, distractibility, experiencing an increase in goal-directed activity or psychomotor agitation, and excessive involvement in pleasurable activities that have a high potential for painful consequences. There must be marked impairment as a result of these symp-toms, and this marked impairment may include becoming psychotic (eg, having grandiose delusions or auditory hallucinations), experiencing a serious impairment in judgment, or needing to be hospital-ized.7Note that in defining mania, the DSM-IV crite-ria specifies an “abnormal” mood; the reference for what is normal may either be the person him- or her-self, or the benchmark may need to be the general pop-ulation, because 1% of persons with bipolar disorder may be in a chronically manic state, and thus they would not meet the criteria if compared with only their own behavior as the standard. Manic symptoms are often the opposite of those of depression (which include depressed mood, psychomotor retardation, a slowing of thoughts) and because of this, individuals often feel unusually productive and creative in the initial manic phase, however, as their condition deteriorates, patients may become increasingly dysfunctional, and even psy-chotic, with severe psychosocial impairment.8

A hypomanic episode includes the same criteria, but is less severe (and often more short-lived) than mania (see Sidebar). While the symptoms clearly rep-resent a change in the behavior and functioning of the

individual, it is not severe enough to cause serious impairment or require hospitalization, nor is psychosis part of the clinical picture. While patients may resist treatment because they are productive and often socially popular in this phase, research indicates that 5% to 15% of persons with hypomania will ultimate-ly develop a manic episode8and also frequent depres-sive incidents.

A mixed mania episode is a period of at least 1 week during which the patient meets the criteria for having a major depressive episode and a manic episode simultaneously. In other words, the patient is in an

Types of Mania

Mania:Abnormally and persistently elevated or expansive mood and 3/7 for 1 week:

• Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity • Decreased need for sleep • Pressured speech

• Flight of ideas or racing thoughts • Distractibility

• Increase in goal-directed activity or psychomotor agitation • Excessive involvement in pleasurable activities that have a

high potential for painful consequences Marked impairment as a result

Hypomania:Abnormally and persistently elevated or expansive mood and 3/7 for 1 week:

• Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity • Decreased need for sleep • Pressured speech

• Flight of ideas or racing thoughts • Distractibility

• Increased in goal-directed activity or psychomotor agitation • Excessive involvement in pleasurable activities that have a

high potential for painful consequences Marked impairment not present

Mixed mania:Abnormally and persistently irritable mood and 4/7 for 1 week:

• Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity • Decreased need for sleep • Pressured speech

• Flight of ideas or racing thoughts • Distractibility

• Increase in goal-directed activity or psychomotor agitation • Excessive involvement in pleasurable activities that have a

high potential for painful consequences Marked impairment as a result

Source: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:345-428.

abnormally and persistently irritable mood, experienc-ing at least 4 of the followexperienc-ing 7 symptoms: inflated self-esteem or grandiosity, decreased need for sleep (eg, feels rested after only 3 hours of sleep), unusually talk-ative/pressured speech, experience flight of ideas or racing thoughts, is easily distracted, has psychomotor agitation, and/or engages excessively in pleasurable activities that have a high potential for dangerous con-sequences (eg, engaging in unrestrained buying sprees, sexual indiscretions, or foolish business investments).7 Again, these symptoms must be sufficiently severe to cause marked impairment in functioning (such as necessitating hospitalization to prevent harm to one-self or others or having associated psychotic features). There may be rapid cycling between moods (depres-sion and euphoria) with mixed mania. Other symp-toms that more commonly accompany mixed mania include: dysphoric mood, emotional lability, anxiety, guilt, suicidality, and irritability.

To summarize, bipolar affective disorders include bipolar I disorder, which includes one or more manic or mixed episodes often alternating with major depres-sive episodes, and bipolar II disorder, which is marked by recurrent major depressive episodes with hypoman-ic episodes. Bipolar disorder is specified as rapid cycling if 4 or more episodes occur within a year. A third type of bipolar disorder, so-called cyclothymic disorder, consists of 2 or more years of mood distur-bance alternating between periods of hypomania and depressive symptoms, although these patients do not meet the criteria for manic or depressive episodes. This condition is common among adolescents (Table). Although individual cases of unipolar

mania have been reported, they are extraordinarily rare.8

SCREENINGTOOLS

Patients may self-administer or be given the MDQ,5,9which screens via 13 yes or no questions for bipolar symp-toms and also includes one co-occur-rence question and one functional impairment question. This survey is available for free online at www. dbsalliance.org.9 Another useful inter-view tool is the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), which is a structured diagnostic inter-view that can be administered in toto in

20 minutes, addresses DSM-IV/International Statistical Classification of Disease and Related Health Problems 10-Axis I, includes a module for mania, con-sists of screening questions followed by formal criteria, and has been tested for sensitivity and specificity.10 Those who screen positive (≥7 symptoms, co-occur-rence, and moderate to severe impairment on the MDQ) should undergo a full clinical evaluation. CLINICALASSESSMENT

Aside from conducting a thorough and longitudi-nal history listening for evidence of manic, hypoman-ic, mixed manhypoman-ic, and/or depressive episodes based on the DSM-IV criteria outlined above, a mental status examination including assessment of the patient’s physical appearance, affect, orientation to their sur-roundings, thought content, judgment or insight, per-ceptions (eg, delusions and hallucinations), and suicidal or homicidal ideation is important.11

In conducting the interview, the clinician should attempt to ascertain the life course of symptoms, begin-ning with the age of onset and also the duration of symp-toms. For example, with regard to depressive episodes, how frequently in a year might the person feel depressed? In bipolar disorder, the type of depression that is present is frequently atypical. This can be evaluated by looking at sleep patterns. Hypersomnic depression should be addressed first, asking the patient to describe what hap-pens to sleep patterns, for instance, do they sleep exces-sively or are they unable to sleep? If it is the case that sleep patterns alternate between hypersomnia and insomnia, bipolar disorder may be present.

on

2

us

gic

he

Table. Bipolar Disorder: Making the Diagnosis

Bipolar Disorder Not

Bipolar I Bipolar II Cyclothymic Otherwise Specified

One or more manic One or more At least 2 years Bipolar features that or mixed episodes, major depressive of numerous do not meet criteria usually accompanied episodes accompa- periods of for any specific by major depressive nied by at least one hypomanic and bipolar disorders

episodes hypomanic depressive

episode symptoms*

*Symptoms do not meet criteria for manic and depressive episodes.

Source: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:345-428.

Since mood is a continuum, to assist the individual in determining when his or her depressive episode ended, ask, “When was the last time you remember feeling consistently well, every day, for 2 months or more?” Ask the patient to describe what they are like when they are well (euthymic), and to try to assist them in gaining perspective, as it is helpful for them to compare themselves and their behaviors and feelings to others. For example, pose these questions: “How many hours do you sleep?” “What’s your energy like com-pared with your friends and colleagues?” “How active are you compared with your friends and colleagues?” and “What’s your ambient mood compared with your friends and colleagues?” By doing this, clinicians create a benchmark in the patients’ minds so they realize what euthymia is. Now the clinician can take the next step to try to establish if there have been hypomanic or manic episodes by asking them, “Have you ever had a time when you’ve been more energetic, more active, got by with less sleep—a time that you might look back at as kind of a golden time in your life when you were very productive?” Posing this question often allows patients to look back with that point of com-parison and to provide clinicians with an indication of symptoms that might not otherwise have been forth-coming from the patient. This is important because sometimes the demarcation for the end of a depressive episode is not euthymia, but rather a switch to anoth-er mood state, such as mania or mixed mania.

Finally, it is vital to ascertain if comorbid condi-tions may be present, such as panic disorder, anxiety, or eating disorders. Whether these are primary or sec-ondary conditions may be determined by examining whether the symptoms are present when the patient feels otherwise euthymic. For example, panic attacks that do not occur when the patient feels euthymic are most likely secondary to the mood disorder and may resolve once the mood disorder is under control. Teasing out all of this information is key to developing an effective treatment plan for each individual patient. MANAGEMENTISSUES FORBIPOLARDISORDER

Management of bipolar disorder will be addressed in detail in the articles that follow. However, in terms of triage, it is important to treat any underlying med-ical conditions first. For example, thyroid and parathy-roid disease can manifest with symptoms suggestive of bipolar disorder (hyperthyroidism may present as

mania; hypothyroidism and hyperparathyroidism as depression). Anemia may be a cause of depression, as can certain electrolyte imbalances. Mental status changes may be present in individuals with AIDS, syphilis, or those using alcohol or illicit substances. Laboratory screening for these conditions is therefore an important part of the workup to rule out other causes of symptoms of depression and/or mania. After medical conditions have been addressed, psychosis is therefore the next critical treatment issue, because it is not possible to treat mood disorders within the context of totally abnormal and unpredictable thought pat-terns. One may now be prepared to treat mood disor-ders, with manic symptoms taking precedence over depression (because mania is a less stable state than depression). If other comorbid conditions are still pre-sent after the patient’s bipolar symptoms have been stabilized, the clinician should address anxiety disor-ders, eating or impulse control disordisor-ders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and personality disor-ders, in that order.

GENETICS AND BIOLOGICALORIGINS OFBIPOLARDISORDER

Exploring the biological origins of bipolar disorder is important to understanding how best to manage these conditions. The lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorder in the general population (risk for an individual or family) is approximately 1%; however, if one has a first-degree relative with the condition, the risk increases to 5% to 10%. Furthermore, the evidence that there are strong genetic roots for this condition comes from the observa-tion that there is up to 75% concordance among monozygotic twins. This is extremely high for medical conditions, and by comparison, the concordance among identical twins for unipolar depression is only 55%.12 Numerous genetic studies of bipolar disorder suggest mutations on multiple genes may be responsible, but, as yet, none have been definitively identified. Candidate gene studies and complete genome screens have provid-ed strong evidence for several potential bipolar disorder susceptibility loci in several regions of the genome, sug-gesting that bipolar disorder susceptibility loci may lie in one or more genomic regions on chromosomes 18, 4, 21, 5, and 8.13

In terms of the anatomy of bipolar disorder, the structures that appear to be very important are the frontal lobe coming down internally into the limbus,

as well as the striatum, and the cerebellum, comprising the limbic-cortical-striatal-pallidal-thalamic tract. Imaging studies, such as positron emission tomogra-phy scans and functional magnetic resonance imaging scans frequently reveal a pattern of dysfunction among these patients. The frontal lobe appears to be hypoac-tive, and this may correspond to the cognitive deficits that we see in bipolar disorder.14

Specifically, the frontal lobe is evidently responsible for inhibiting certain deep structures, thus, if it is less active, deeper structures may become too active. This results in amygdalar hyperactivity, with associated psy-chomotor and hedonic dysregulation. The cerebellum also becomes hyperactive. Cerebellar hyperactivity may account for emotional and cognitive dysregula-tion while dysreguladysregula-tion of the hippocampus seems to be responsible for sleep and endocrine dysfunction that may be observed in affective disorders.14

Finally, on the intracellular level, antidepressants and mood stabilizers appear to have a variety of neurotroph-ic effects. Antidepressants increase neuronal sprouting, neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and exert positive behavior effects via increases in essential neurochemicals, such as brain-derived nerve growth factor and intrinsic tyrosine kinase. Mood stabilizers, on the other hand, are neurotropic via their actions on other cellular substances, such as the reduction of protein kinase C, myristolated alanine-rich C kinase substrate, and the increase in oth-ers, including beta catenin, ribosomal S6 kinase, and cyclic AMP response element binding protein.15 In the section that follows, pharmacologic treatment strategies based on what is known about the biochemistry of bipo-lar disorders will be explored.

REFERENCES

1. National Institute of Mental Health. The numbers count: Mental disorders in America. Available at:

http://www.nimh.gov/publicat/numbers.cfm. Accessed November 7, 2004.

2. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK. The de facto mental and addictive disorders service system. Epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and ser-vices. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(2):85-94.

3. Narrow WE. One-year prevalence of depressive disorders among adults 18 and over in the US: NIMH ECA prospec-tive data. Population estimates based on US Census esti-mated residential population age 18 and over on July 1, 1998. Unpublished table.

4. Angst J. The emerging epidemiology of hypomania and bipolar II disorder. J Affect Disord. 1998;50(2-3):143-151. 5. Hirschfeld RM, Calabrese JR, Weissman MM, et al.

Screening for bipolar disorder in the community. J Clin Psychiatry.2003;64(1):53-59.

6. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disor-der. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(6):530-537. 7. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistic

Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

8. Compton MT, Nemeroff CB. Depression and bipolar disor-der. Available at: http://www.acpmedicine.com/cgi-bin/publiccgi.pl. Accessed November 7, 2004. 9. Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance. The Mood

Disorder Questionnaire. Available at: http://www.dbsal-liance.org/questionnaire/screening.asp. Accessed November 7, 2004.

10. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the develop-ment and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22-33.

11. Soreff S, McInnes LA. Bipolar affective disorder. Available at: http://www.emedicine.com/med/topic229.htm. Accessed November 7, 2004.

12. Taylor L, Faraone SV, Tsuang MT. Family, twin, and adop-tion studies of bipolar disease. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4(2):130-133.

13. Mathews CA, Reus VI. Genetic linkage in bipolar disorder. CNS Spectr.2003;8(12):891-904.

14. Post RM, Speer AM, Hough CJ, Xing G. Neurobiology of bipolar illness: implications for future study and therapeutics. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2003;15(2):85-94.

15. Coyle JT, Duman RS. Finding the intracellular pathways affected by mood disorder treatments. Neuron. 2003;38(2):157-160